1. Introduction

Italy is one of the developed countries in Europe and one of the major economies in the world; however, the economy of Italy has struggled much since 1990. The Italian economy’s struggle can be represented as a downturn in the economy, which is manifested in low GDP growth rates. One of the major reasons for Italy’s economic struggle is the lack of exports. According to Keynesian economic theory, exports, aggregate demand, and investment are the three main factors that directly influence economic growth, while exports and aggregate demand in Italy have stagnated. Joining the Eurozone has created a negative effect on Italy’s exports and aggregate demand because joining the Eurozone led to the loss of Italy’s currency and independent monetary policy and the ability to independently regulate its own currency to stimulate economic development. At the same time, manufacturing has been Italy’s core industry since the 1950s, and the downturn in the Italian manufacturing sector after 1990 has also placed a huge burden on the Italian economy. The downturn in the Italian manufacturing sector was the reason for the lack of exports and also led to the weakness of domestic consumption. In addition, the competition between other newly industrialised countries and Italy in the same period also reduced the export and manufacturing advantages of Italy, which further deprived the world market of Italian manufacturing.

2. Lack of Exports

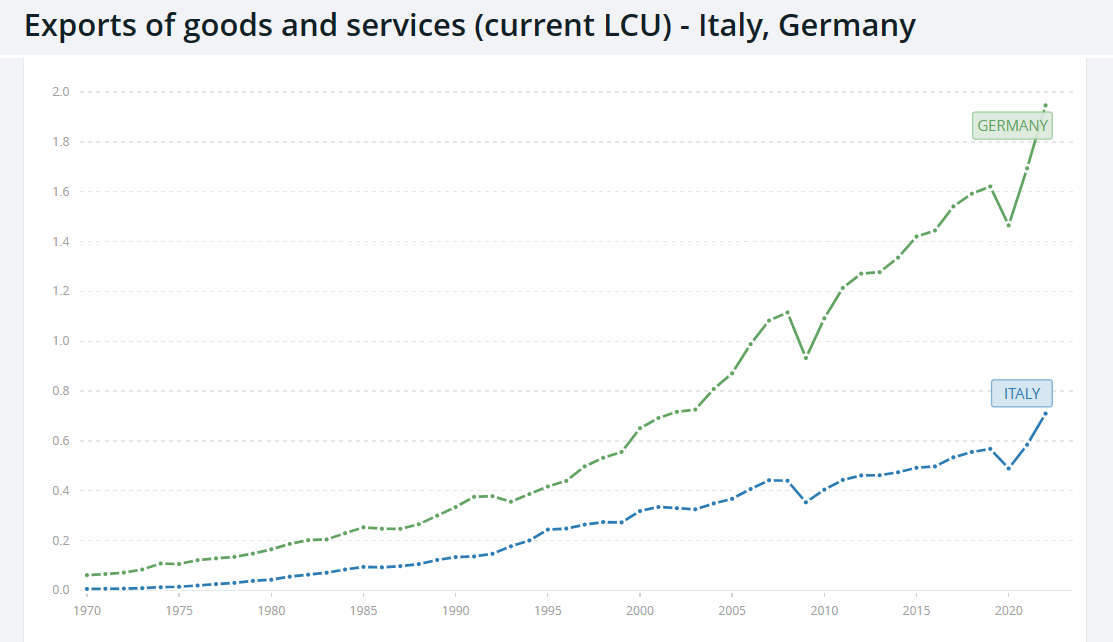

Firstly, one of the major reasons for Italy’s economic struggle is the lack of exports. According to Keynesian economic theory, exports are one of the three main factors that directly affect a country’s economic growth [1]; therefore, the lack of exports in Italy has a serious negative impact on the Italian economy. Italy also had a strong manufacturing system, which became one of its core industries. However, unlike other manufacturing powerhouses such as Germany, Italy does not use exports as its main economic orientation. As a result, figure 1 presents that Italy’s export growth has been much lower than Germany’s during the same period [2].

Figure 1: Exports of goods and services (current LCU), Italy and Germany [2].

2.1. Membership of the Eurozone

A major reason for Italy’s low exports was that it became a member of the Eurozone. Italy already had a relatively mediocre export performance before 1990, and after joining the Eurozone, it was more constrained by the economic community. Therefore, Italy’s export growth figures, while not falling into a downward trend, fell into a mediocre trend that was difficult to rescue after 1999 [2].

Exports need to compete on price with other countries of the same period. There are two main ways to compete on price: the first is to reduce costs, and the second is to reduce the exchange rate. However, after joining the Eurozone, Italy was no longer able to reduce the price of its exports through exchange rate depreciation in order to gain more competitive advantages in the international market.

The creation of the Eurozone represents an extremely high degree of economic integration among the Eurozone member countries, including Italy, to the extent of depriving them of part of their financial autonomy. The most direct effect of economic policy integration in the Eurozone on Italy was the replacement of Italy’s original currency, the lira, with a unified currency, the euro, and the issuance of monetary policy through a unified European Central Bank [3]. As a member of the Eurozone, Italy no longer has an independent currency and has lost the freedom to regulate its own exchange rate. Using loose monetary policy can help Italy moderate prices, but the unified currency stops Italy from adjusting its own monetary policy [4]. The unification of currency and monetary policy meant that Italy could not attract more export trade through loose monetary policy, such as devaluing its own currency.

From this point of view, Italy’s export slump is related to the fact that its main measures to promote exports have been limited for external reasons. In addition, since Italy is a member of the Eurozone, these external reasons cannot be solved for a long time without an exit from the Eurozone.

2.2. Low-end Manufacturing

Another reason for the weakness of Italian exports is the high degree of substitutability of export products [1]. The industrialization course of Italy was relatively late compared to other Western European countries; while most industrial countries already had a strong industrial base in the early 20th century, Italy was still greatly characterised by an agrarian society during this period. Therefore, in the early 20th century, when Italy was seen as a conservative country and a region of emigration, a large number of Italians emigrated to various European countries to search for work [5]. Italy gradually began to industrialise on a large scale after World War II, and its industrialization continued at a fast pace from the 1950s to the 1970s [6]. As a result, Italy was relatively behind on its industrialization course compared to older industrial countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom. As a latecomer industrial country, Italy occupied more of the low-end manufacturing industries, while most of the old developed countries, such as the United States, had already gradually abandoned the low-end manufacturing industries. By 1990 onwards, Italy’s exports also included a portion of high-end manufacturing but remained mostly dominated by traditional low-end manufacturing [6].

However, the biggest defect of Italian manufacturing industries is that these industries are highly substitutable, especially when facing the exports of the newly industrialised countries in the 1990s, which meant Italy lacked industrial advantages [7]. These newly industrialised countries often lacked the technological base of high-end manufacturing and were unable to technologically threaten to displace the high-end manufacturing countries. Even though these newly industrialised countries had some high-end manufacturing capacity, they were still unable to outperform the developed industrial countries in terms of manufacturing costs and product quality.

As the “factory of the world”, the manufacturing cost of these low-end manufacturing countries is far lower than that of the old developed countries, and the manufacturing scale is strong enough to challenge the old industrial countries and meet the needs of the whole world. These emerging countries have acted more as suppliers of materials to high-end manufacturing countries that no longer need to produce low-end manufacturing products; their relationship with developed countries is mostly cooperative rather than challenging or fighting in international trade.

However, the relationship between Italy and newly industrialised countries was closer to competitive. Although Italy was once regarded as a powerhouse, it was not actually an old industrial country. The industrial development of Italy was most rapid in the 1960s and 1970s, and thus Italy was closer to the newly industrialised countries than to the former powers with a strong industrial base, such as Britain and Germany [6]. The rise of newly industrialised countries is a huge threat to Italy’s international market share. The low-end manufacturing products of the newly industrialised countries, especially textiles, chemicals, and metal products, gained a significant position in world trade in the 1990s and also succeeded in obtaining a huge share of the international market because of their advantages of lower cost and lower price.

One of the most representative emerging industrial countries in the 1990s was South Korea, which was also one of the countries that seized the largest share of the market in the 1990s [7]. South Korea was the most representative example of the serious challenge to the export of Italian products. In addition, Italy’s exports not only competed in the international market with other emerging industrial countries that were developing rapidly in the same period but also allowed China and other emerging industrial countries to basically complete the seizure of market share. Italy was actually the failure in this trade competition during the 1990s, which is undoubtedly a huge blow to Italy’s local manufacturing and export ratio.

In conclusion, one of the main reasons for Italy’s weaker exports is its membership in the Eurozone, which has resulted in Italy’s inability to actively devalue its currency to attract exports. The second factor is that Italy’s manufacturing sector is dominated by low-end manufacturing, which competes heavily with the industrialised countries that emerged in the 1990s in terms of industry. The decline in international market share led to a decline in exports.

3. Demand

3.1. EU Membership and the Lack of Aggregate Demand

An important reason for the Italian economic struggle is the lack of aggregate demand. According to Keynesian economic theory, aggregate demand is one of the three main factors in real GDP growth, and its importance is the same as that of exports. Therefore, the lack of demand will also directly contribute to the slow growth of real GDP [8].

As with exports, joining the Eurozone has also hit Italy’s aggregate domestic demand. As a highly integrated economic community, the Eurozone mainly united the currencies of many of Europe’s strong economies. However, the European Central Bank’s conformity of monetary policy across Eurozone member states was also a constraint on some Eurozone members’ ability to adjust their own economic policies [3]. For Italy, the loss of autonomous monetary policy is also a terrible limitation on the consumption boost. The unified monetary policy controlled by the European Central Bank directly leads to a lack of ways to control domestic demand.

Therefore, since joining the Eurozone, the existence of the European Central Bank and the loss of independent and autonomous monetary policy have caused macroeconomic regulation and means to stimulate the economy to be limited in Italy.

Firstly, Italy is unable to provide more funds to residents and enterprises to boost consumption and production through loose monetary policy, such as issuing more money to society. Especially when small and medium-sized enterprises are facing difficulties, they cannot obtain more credit funding support from the government [9].

Secondly, Italy’s government is also unable to reduce domestic interest rates to reduce costs for consumers and producers, thereby improving the financial situation of businesses and consumers [5].

Moreover, the Eurozone has not adopted an interest rate reduction policy that would support Italy’s economic recovery. The Eurozone is facing an inflationary problem in most of its member states; therefore, it has adopted a policy of raising interest rates, which actually dealt a second blow to the Italian economy [10].

The loss of monetary policy, one of the most important macroeconomic regulation instruments, caused the Italian government to become powerless while facing the economic downturn and the lack of domestic demand, unable to solve the problem of low consumption on its own as an Eurozone member state.

3.2. Unemployment

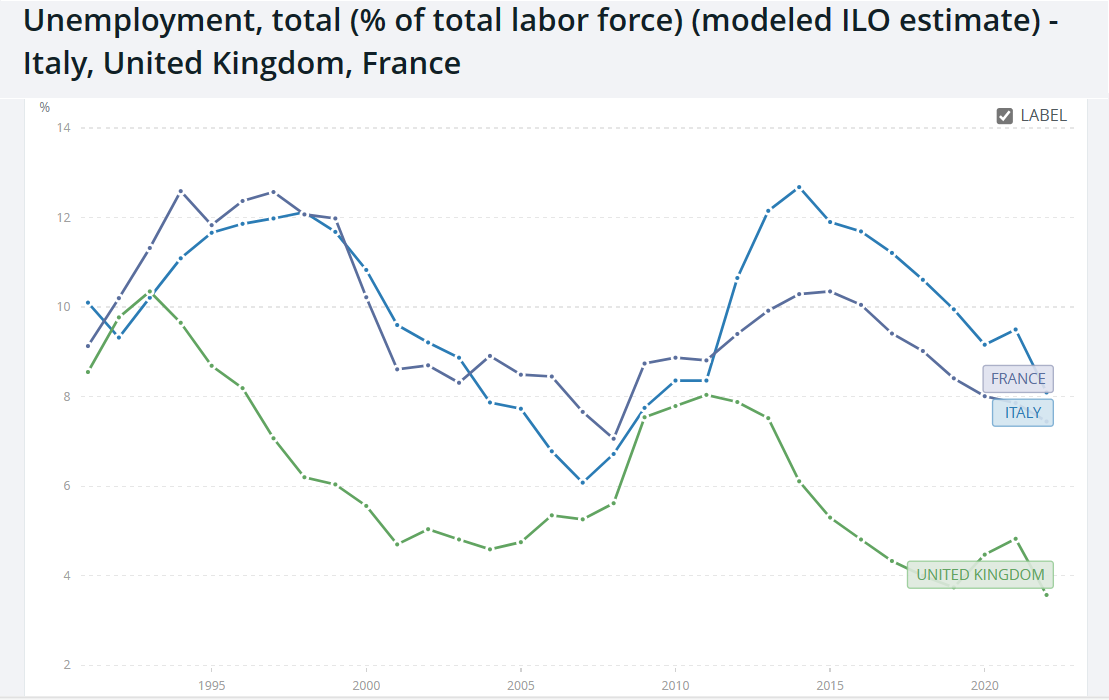

Furthermore, unemployment in Italy has been another important cause of the prolonged slump in aggregate demand. The Italian labour market has an inflexible character, similar to that of France during the same period. Highly flexible labour markets, such as the labour market of the United Kingdom in the post-1990 period, is a market which most groups of people can obtain a stable but low-wage job, and the flexible labour market maintained a low unemployment rate for many years. In contrast, the inflexible labour markets in France and Italy allowed groups of participants to generally have more chances to earn a higher wage but also fostered a relatively severe unemployment problem [11]. Against a background of mediocre economic growth, not only does unemployment remain high, but the unemployed are trapped in long-term unemployment. According to figure 2, Italy has maintained a high unemployment rate of 9–10% for a long time, since 1992 [11].

Figure 2: Unemployment rate of Italy, the United Kingdom, and France [11].

Furthermore, the high unemployment rate in Italy also has a social factor. Some groups of people in Italy are actively unemployed and actually voluntarily decide to join the unemployed population [12]. This social phenomenon is related to the nice welfare policy in Italy. Italy’s welfare policy ensures that many Italians are able to maintain a poor but normal lifestyle without being employed, which causes being unemployed and having no job to become a normal and common behaviour in Italian society. However, in an environment of high unemployment, it is difficult to boost consumption in Italian society. Long-term and widespread unemployment has caused a large number of Italians to lack a stable source of income.

Even though Italy’s welfare policies have provided a favourable environment for these people to survive, the unemployed still do not have access to sufficient funds to consume in large quantities. In this environment, a significant part of the population is not only unable to consume but also lacks the will to consume. This expresses that a significant proportion of Italians are unable to provide consumption for Italian society and has become one of the underlying reasons why Italy’s domestic demand has come to a standstill for years.

In conclusion, low domestic demand is one of the central factors in the struggle of the Italian economy, which is caused by the unified monetary policy under the economic community and a serious unemployment problem due to the inflexible labour market. Joining the Eurozone limited Italy’s macroeconomic policy. Furthermore, the monetary policy adopted by the Eurozone not only fails to solve the domestic demand deficit faced by Italy but also aggravates the problem. Widespread unemployment has also led to a widespread refusal to consume in Italy, which causes domestic demand to suffer.

4. Manufacturing Sector

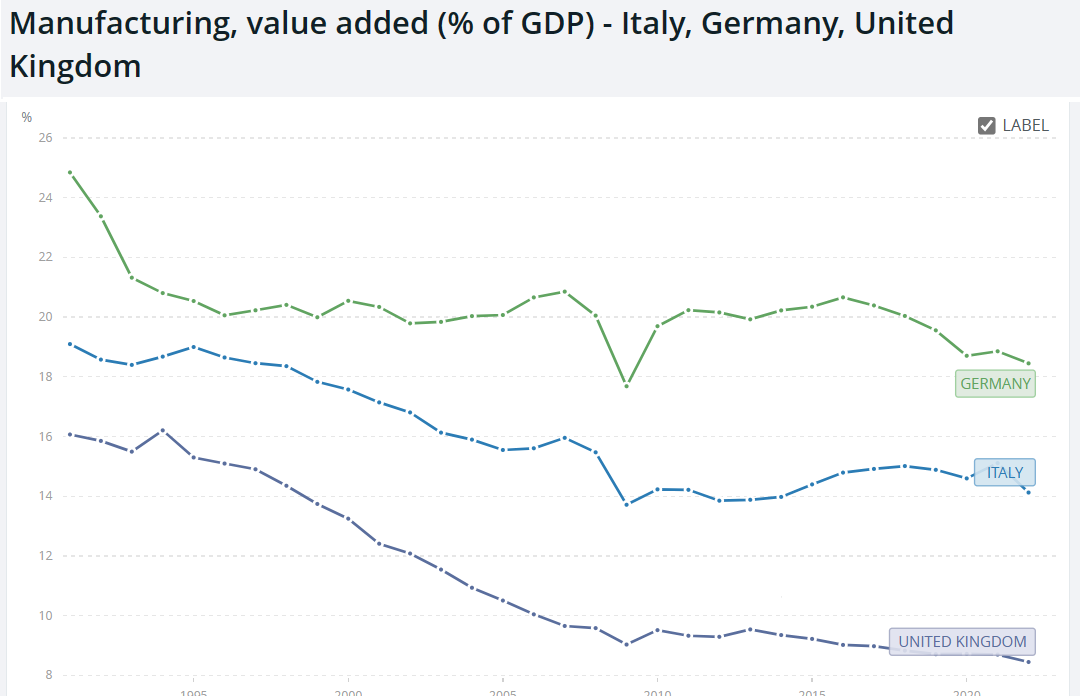

4.1. Labour Market

Thirdly, one of the most important reasons for the struggle in the Italian economy is the sluggishness of the Italian manufacturing sector. The process of industrialization in Italy was slower compared to other Western European countries, and the transformation from an agrarian society to an industrial society was only completed in the 1960s and 1970s. As a result, the Italian industry in the 1990s was dominated by manufacturing, as shown in Figure 3, and the share of manufacturing in Italy was higher compared to developed countries such as the United Kingdom in the same period [13]. In the context of a manufacturing-dominated industry, the weakness of the Italian manufacturing sector had a greater impact on the economy.

Figure 3: Manufacturing value of Italy, Germany, and United Kingdom [13].

One of the reasons for the sluggishness of the Italian manufacturing sector is the inflexible labour market. One of the main features of an inflexible labour market is that workers generally have higher wages and more opportunities for wage growth. This is because workers are less substitutable; therefore, they generally gain some bargaining power. As a result, because of the inflexible labour market, labour costs in Italy have not only remained high but have also risen [14].

Furthermore, an inflexible labour market not only causes higher labour costs but also higher costs for companies. Italy’s labour market problems, on the one hand, caused an increase in the price of goods, which made enterprises less competitive and limited sustainable development. On the other hand, the profitability of enterprises is also challenged [6].

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Italian manufacturing industry was dominated by small and medium-sized enterprises, while large enterprises were fewer in number and mainly located in the northern region of Italy [6]. Most of the Italian small and medium-sized enterprises in this period still followed the traditional business model, which relied on the advantage of low-cost labour to achieve profitability and maintain a sound business operation [6]. The Italian labour market in the 1960s and 1970s institutionally relied on the support of local forces such as the “extended family” to structure the labour market. These ‘extended families’ were very influential in the local regions and had the ability to suppress the bargaining power of workers to the greatest extent [6].

This is the reason why the Italian labour market used to be low-wage and low-cost, and it is one of the foundations of the Italian manufacturing industry. Traditional manufacturing enterprises relied on low-wage labour to avoid financial burdens and maintain profitability. When this advantage became a burden, enterprises faced difficulties in surviving and growing. When Italy gradually lost the low-cost labour advantage of the small and medium-sized enterprises of the 1970s, the manufacturing industries lost their competitiveness in the global market. As a result, Italy’s manufacturing sector began to suffer from a deficiency of growth and expansion in the 1990s.

4.2. Decline in Domestic Demand

In addition, the decline in domestic demand also hit Italian manufacturing. As mentioned above, the weakness of domestic demand in Italy after 1990 is related to the high unemployment rate of 9–10% that Italy has maintained for a long time [11]. The high unemployment rate not only hit people’s ability and willingness to consume but also dealt a fatal blow to the manufacturing sector. When Italians reduce their consumption for various reasons, Italian manufacturing companies are faced with the dilemma of producing goods that no one buys.

For enterprises, sales volume of goods and labour costs are the most important and intuitive indicators, and low sales value directly leads to a decline in corporate income. When the income of enterprises becomes difficult to maintain, direct means of reducing expenditures, such as layoffs, are necessary for the operation of the enterprise. The employment rate of the Italian manufacturing industry during the 1990s maintained a downward trend of about 0.5% per year [11]. It can be seen that layoffs in the manufacturing industry are a widely occurring social phenomenon.

Layoffs in manufacturing companies not only led to the stagnation of the manufacturing sector, but more seriously, the downturn in the manufacturing sector was a problem that could not be solved by Italy itself. When factories have to lay off workers in order to maintain the profitability of the enterprise, the unemployment rate will undoubtedly remain high with the reduction of jobs provided by the enterprise.

Besides, a high unemployment rate also leads to the loss of sufficient sources of income for some groups of people to continue consuming, as well as a decline in the willingness and ability of society to consume. In either case, the lack of consumption leads to a sustained decline in aggregate demand in Italy. Which is a vicious circle of persistently high unemployment and persistently declining aggregate demand. The continuation of the vicious circle has led to the fact that Italy has not had the appropriate means to address the difficulties faced by the manufacturing sector since 1990.

In conclusion, as one of the core industries in Italy, Italy’s manufacturing sector also stagnated after 1990. In an economic environment where the core industry is in the doldrums, Italy’s economy must be difficult to develop. The reasons for the downturn in the Italian manufacturing industry are also numerous. Firstly, Italy’s manufacturing sector is in a depression because of the inflexible labour market. The inflexible labour market has caused an increase in the labour costs of workers, which reduces the profitability of enterprises and their competitiveness in the face of other countries. Secondly, the downturn in Italian manufacturing is also related to the lack of aggregate demand. Low aggregate demand and high unemployment have become a vicious circle that has long plagued the Italian manufacturing sector.

5. Conclusion

According to Keynesian economic theory, the decadence of exports and aggregate demand have become important reasons for the struggle of the Italian economy. In addition, the stagnation of the core industry of manufacturing has also severely attacked the Italian economy. The monetary policy of the Eurozone does not support the recovery of the Italian economy and has become an obstacle to the recovery of the Italian economy. Besides, the lack of mobility in the Italian labour market has also become one of the reasons for the struggles of the Italian economy. The two main features of the inflexible labour market are the high chance of wage increases and the high unemployment rate, which have imposed a great burden on the Italian economy, especially the manufacturing industry. High wages equal higher costs for Italian businesses, while high unemployment is directly related to consumption in the country. States with high unemployment have a large portion of the population that has lost their ability or willingness to consume, which is extremely detrimental to economic development. For the manufacturing sector, the lack of domestic demand in the country can also lead to producing fewer products and falling into a vicious circle that cannot be regulated. In addition, there are still other factors that lead to economic struggle in Italy, such as the north-south economic difference in the Italian economy, where the economic conditions and industries in southern Italy are far weaker than those in northern Italy, so that southern Italy has become a serious burden to the whole Italian economy.

References

[1]. Palley, T. I. (2012) ‘The Rise and Fall of Export-led Growth’, Investigación Económica, 71(280), pp. 141-161.

[2]. The World Bank (2023) Exports of goods and services (current LCU) - Italy, Germany | data. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.EXP.GNFS.CN?locations=IT-DE&name_desc=false (Accessed: 04 September 2023).

[3]. European Central Bank (2023) The euro, European Central Bank. Available at: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/euro/html/index.en.html (Accessed: 04 September 2023).

[4]. Taylor, J.B. (2001) ‘The Role of the Exchange Rate in Monetary-Policy Rules’, The American Economic Review, pp. 263-267.

[5]. Camiscioli, E. (2001) ‘Producing Citizens, Reproducing the ‘French Race’: Immigration, Demography, and Pronatalism in Early Twentieth-Century France,’ Gender & History, pp. 593-621.

[6]. Quatraro, F. (2009) ‘Innovation, structural change and productivity growth: Evidence from Italian regions, 1980-2003’, Cambridge Journal of Economics, 33(5), pp. 1001-1022.

[7]. The World Bank (2023) Manufacturing, value added (annual % growth) - Italy, Poland, Korea, Rep. | Data. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NV.IND.MANF.KD.ZG?end=2009&locations=IT-PL-KR&start=1991 (Accessed: 04 September 2023).

[8]. Nell, K. S. (2012) ‘Demand-led versus supply-led growth transitions’, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 34(4), pp. 713-747.

[9]. Hughes, K. (2011) ‘Where Next for a Europe in Crisis?’, Economic and Political Weekly, 46(46), pp. 25-27.

[10]. Farrell, H. and Quiggin, J. (2011) ‘How to Save the Euro—and the EU: Reading Keynes in Brussels’, Foreign Affairs, 90(3), pp. 96-103.

[11]. The World Bank (2023) Unemployment, total (% of total labor force) (modeled ILO estimate) - Italy, United Kingdom, France | Data. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.TOTL.ZS?locations=IT-GB-FR (Accessed: 06 September 2023).

[12]. Browne, J., Pacifico, D. (2016) ‘Faces of joblessness in Italy: anatomy of employment barriers’, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, pp. 7-33.

[13]. The World Bank (2023) Manufacturing, value added (% of GDP) - Italy, Germany, United Kingdom | Data. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NV.IND.MANF.ZS?end=2022&locations=IT-DE-GB&start=1990 (Accessed: 06 September 2023).

[14]. The World Bank (2023) Wage and salaried workers, total (% of total employment) (modeled ILO estimate) - Italy | Data. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.EMP.WORK.ZS?locations=IT (Accessed: 06 September 2023).

Cite this article

Shi,S. (2023). Why Has Italy Struggled So Much to Grow Economically Since 1990?. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,32,82-89.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the International Conference on Global Politics and Socio-Humanities

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Palley, T. I. (2012) ‘The Rise and Fall of Export-led Growth’, Investigación Económica, 71(280), pp. 141-161.

[2]. The World Bank (2023) Exports of goods and services (current LCU) - Italy, Germany | data. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.EXP.GNFS.CN?locations=IT-DE&name_desc=false (Accessed: 04 September 2023).

[3]. European Central Bank (2023) The euro, European Central Bank. Available at: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/euro/html/index.en.html (Accessed: 04 September 2023).

[4]. Taylor, J.B. (2001) ‘The Role of the Exchange Rate in Monetary-Policy Rules’, The American Economic Review, pp. 263-267.

[5]. Camiscioli, E. (2001) ‘Producing Citizens, Reproducing the ‘French Race’: Immigration, Demography, and Pronatalism in Early Twentieth-Century France,’ Gender & History, pp. 593-621.

[6]. Quatraro, F. (2009) ‘Innovation, structural change and productivity growth: Evidence from Italian regions, 1980-2003’, Cambridge Journal of Economics, 33(5), pp. 1001-1022.

[7]. The World Bank (2023) Manufacturing, value added (annual % growth) - Italy, Poland, Korea, Rep. | Data. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NV.IND.MANF.KD.ZG?end=2009&locations=IT-PL-KR&start=1991 (Accessed: 04 September 2023).

[8]. Nell, K. S. (2012) ‘Demand-led versus supply-led growth transitions’, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 34(4), pp. 713-747.

[9]. Hughes, K. (2011) ‘Where Next for a Europe in Crisis?’, Economic and Political Weekly, 46(46), pp. 25-27.

[10]. Farrell, H. and Quiggin, J. (2011) ‘How to Save the Euro—and the EU: Reading Keynes in Brussels’, Foreign Affairs, 90(3), pp. 96-103.

[11]. The World Bank (2023) Unemployment, total (% of total labor force) (modeled ILO estimate) - Italy, United Kingdom, France | Data. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.TOTL.ZS?locations=IT-GB-FR (Accessed: 06 September 2023).

[12]. Browne, J., Pacifico, D. (2016) ‘Faces of joblessness in Italy: anatomy of employment barriers’, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, pp. 7-33.

[13]. The World Bank (2023) Manufacturing, value added (% of GDP) - Italy, Germany, United Kingdom | Data. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NV.IND.MANF.ZS?end=2022&locations=IT-DE-GB&start=1990 (Accessed: 06 September 2023).

[14]. The World Bank (2023) Wage and salaried workers, total (% of total employment) (modeled ILO estimate) - Italy | Data. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.EMP.WORK.ZS?locations=IT (Accessed: 06 September 2023).