1. Introduction

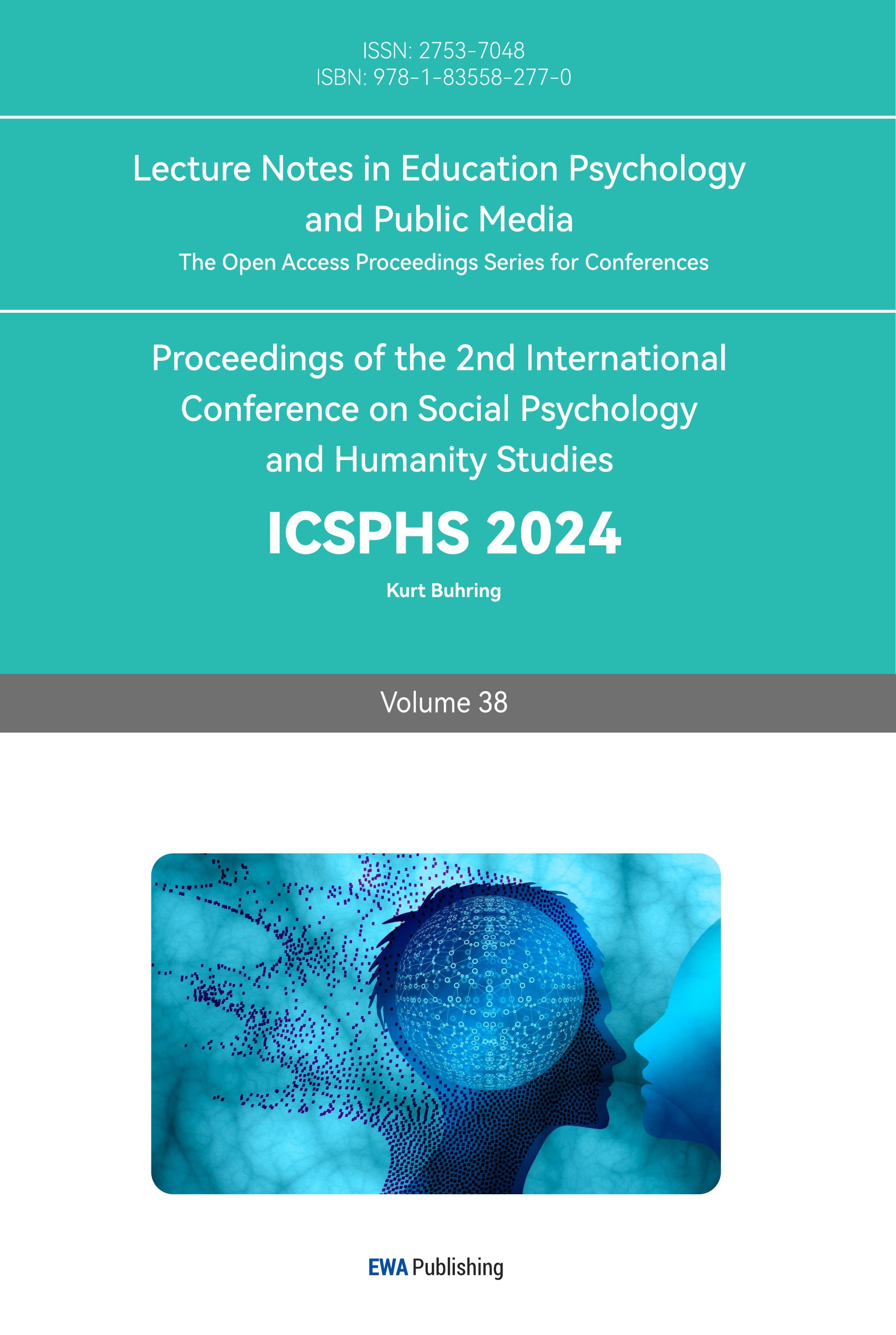

Figure 1: Nishida Kitaro - Japanese Philosophe.

No one shaped modern Japanese philosophy as significantly as did Nishida Kitaro (1870-1945). A graduate of Tokyo Imperial University, Nishida studied Western philosophy—from Immanuel Kant to David Hume, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel to Friedrich Nietzsche—in the classroom and then pursued Zen Buddhism under Suzuki Daisetsu, a prolific Buddhist scholar who introduced Eastern philosophy to the West through his English-language publications. In 1911, when Nishida was a philosophy professor at Kyoto Imperial University at age 41, he penned An Inquiry into the Good, the seminal text of “Nishida philosophy”, which combined Western philosophy and Eastern philosophy, including Buddhism, to reach a new understanding of the world. He also created the so-called Kyoto School (京都学派), a group of philosophers based at Kyoto Imperial University, who eventually claimed the superiority of Eastern philosophy over Western philosophy, a view that was co-opted by the military in the 1930s and 1940s. Though usually not seen as a political figure, Nishida, and his thought, was deeply embedded in imperial Japan, particularly its quest for the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere (大東亜共栄圏).

The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere was the central ideology that underlay the Japanese empire as it expanded into the Asia-Pacific in the 1940s. Prime Minister Konoe Fumimaro’s first cabinet launched the New East Asian Order (東亜新秩序) in 1938, in the maelstrom of the Second Sino-Japanese War, and his second cabinet elevated it into the Co-Prosperity Sphere in 1940, which encompassed not only East Asia (Japan, China, and Manchuria), but also Southeast Asia (the Philippines, Thailand, Burman, India, Indochina, Malaya, Brunei, and Indonesia). Deriving from Pan-Asianism and led by the slogan “Eight Corners of the World under One Roof” (八紘一宇), the Co-Prosperity Sphere promised to liberate these countries and regions from Western imperialism and integrate them into a singular entity under the benevolent leadership of Japan. In 1943, Prime Minister Tojo Hideki’s cabinet convened the Greater East Asia Conference in Tokyo. By that time, however, the prospects of Japan’s victory in the Pacific War had grown slimmer than ever. The conference was a last-minute attempt to justify the already-defeated war, and the visions for the Co-Prosperity Sphere expressed at the conference were never implemented.

The historiography on the Japanese empire is vast. Scholars traditionally studied Japan’s seemingly irrational decision-making for the Second Sino-Japanese War and Pearl Harbor, with special focus on its search for economic security [1]. In the past quarter century, scholars have also examined the economic and cultural dynamics of the Japanese empire. Japan’s empire-making and war-making were promoted by their economic interest as well as the culture of total war, created by media, intellectuals, and ordinary citizens [2]. More recently, historians have expanded their scope of research from Japan and its near colonies, including Korea, Taiwan, and Manchuria, to Southeast Asia and the Pacific, to analyze the making and unmaking of its Pan-Asian ideology—something that was created by Japanese officials, but co-opted by colonial elite [3]. Japanese of all walks of life participated in one way or another in empire-building and war-making, from journalists to scholars to religious leaders, not only Shintoists, but also Christians and Buddhists [4]. Yet few scholars have analyzed the role of Nishida Kitaro despite his unique position in the Japanese empire as a leading multi-religious philosopher.

The literature on Nishida Kitaro centers around his philosophy, particularly An Inquiry into the Good. Takayama Gando, Sasagawa Ryoichi, Kamiya Mieko, Hisagi Yoshiharu, and John Krummel have all extensively examined the expansive body of Nishida’s philosophical work. They highlighted its emphasis on the relationship between individual self-practice and absolute existence—the unique “self-transcendence philosophy” (自己を超越する哲学), which highlights the importance of surpassing limitations of self-consciousness to achieve self-perfection and experience absolute existence. It was a distinct “absolute non-self”(絶対の無我) philosophy, which stressed the merging of the self with the absolute non-self for self-liberation and self-transcendence. These scholars all underscored Nishida’s role in the development of Japanese philosophy, as well as his insights and influence on Western philosophy, particularly his non-dualistic approach guiding individuals to transcend binary oppositions and subjective-objective limitations to achieve self-identity and discover absolute existence [5]. Besides his unique philosophy, however, few scholars have written about his politics.

This paper examines Nishida’s role in the Japanese empire, particularly his relationship with the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. It pays special attention to “The Principle of the New World Order,” an essay that Nishida drafted in 1943 in response to the government’s request. The essay, full of complexity and contradiction, shed light on the crossroad of his views on philosophy, Pan-Asianism, and imperialism. I argue that Nishida, far from an “imperial collaborator,” tried to reconcile his philosophy with the Co-Prosperity Sphere, an attempt that proved abortive due to the inherent tension between the two. The first and second parts of this paper briefly discuss Nishida’s philosophical thought and political life. The third part offers a brief survey of Pan-Asianism, a distinct component of the Co-Prosperity Sphere. The fourth part critically analyzes Nishida’s “The Principle of the New World Order,” from its background to content to afterlife. The conclusion examines Nishida’s posthumous evaluations, as well as how his case can illuminate the nature of the Japanese empire.

2. Nishida’s Philosophy

In his An Inquiry into the Good and other works, Nishida Kitaro’s philosophical thought mainly revolves around the issues of the true self and moral behavior. He introduces the concepts of “absolute reality” (絶対の真実) and “value” (価値) to explore these issues. On “absolute reality,” Nishida argues that for a human to understand the world in which he or she lives, that person needs to transcend the self and establish a connection with the world outside—or the “absolute reality” as he calls it—in which that person is interrelated and interdependent with other persons, rather than existing in isolation. On “value,” Nishida explains that it lies at the core of human behavior. He categorizes value into two types: absolute value and relative value. The first is something universal and eternal, such as truth, goodness, and beauty—values that he considers worthy of pursuing—while the second pertains to individual preferences and desires. Combining his definitions of “absolute reality” and “value,” Nishida suggests that only by considering the needs and interests of others, who also exist in the same world, can individuals transcend their own self-interests, realize the true self, and achieve moral behavior. An Inquiry into the Good had a profound impact on the development of Japanese philosophy and ethics, inspiring further research on subjectivity, self-practice, and moral concepts.

Believing that spiritual practice and awakening were key to self-transcendence and moral behavior, Nishida incorporated elements of Western and Eastern religion in his philosophy. Christianity, particularly the notions of religious experience and personal redemption, was at the center of discussion in his works. Nishida emphasizes the relationship between the individual and the “Absolute Reality,” that is, God, asserting that through this connection, individuals can achieve self-transcendence. Nishida also studied Zen Buddhism, which, like Nishida’s philosophy, pursued liberation and enlightenment. He incorporated the concept and practice of meditation (座禅) and awakening (悟り), through which he believed individuals can transcend personal desires, and achieve the true self and moral behavior. The concepts of morality, ethics, and benevolence in Confucianism also shaped Nishida’s philosophy. For him, these values provided guidance on how to achieve self-transcendence and moral behavior, which, in turn, would foster the sense of social responsibility in individuals. With his religious eclecticism, Nishida explored the interconnectedness between the individual, the Absolute Reality, others, and the world, themes that underlay the large body of his philosophical work.

3. Nishida’s Political Life

Unlike many of his colleagues at Kyoto Imperial University, Nishida was never deeply involved in politics, which saved him from prosecution that befell anyone who dared to oppose the government in the tense political atmosphere of the 1930s and 1940s. He did not insulate himself from the world around him, however, According to Michiko Yusa, Nishida was highly critical of Japanese militarism, which was getting out of control. In the wake of the May 15 Incident in 1932, in which a flock of young officers assassinated Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi and ended party politics in Japan, he wrote to his friend: “It is as if the country has turned to anarchy. I wonder what the next cabinet is going to be like.” Then, after the February 26 Incident in 1936, in which young Imperial Japanese Army officers, numbering 1,400, killed three cabinet ministers, Nishida accused the rebels of “cruel violence” that was causing “destruction of the country.” “From now on, the military will begin to control Japan,” he predicted. Nishida also quietly protested the restrictions on freedom of speech and education through his lectures and publications, and lamented Pearl Harbor in his private correspondence as evidence of Japanese leaders’ lack of knowledge about the world. He and his fellow philosophers in the Kyoto School, with a trail of Western influence, nonetheless faced increasing accusations by ultranationalists, who threatened their lives. Nishida had to stay low [6].

Nishida’s attitude toward the emperor and the imperial household was far more nuanced than his criticism of Japanese imperialism. In his Issues in Japanese Culture (日本文化の問題), Nishida depicted the emperor as “nothingness” and “the world”—something similar to the “absolute reality”in his An Inquiry into the Good. He argued that the imperial household existed for thousands of years in Japan despite countless commotions surrounding it, from war to famine to revolution, which made the emperor something that, in his mind, preceded all other existence. Nishida explained that the world should be governed in the same way, with the Japanese emperor being the “absolute reality.” Not unlike Nietzsche’s “superman,” Nishida entertained the concept of the “great person,” namely the emperor, who would function as the “ultimate moral authority” in the family of nations [7]. Despite the purported superiority of Japanese culture over Western culture in his philosophical thinking, Nishida never advocated forceful expansion of the imperial rule. He envisioned that the adoption of the imperial system in the wider world should take place naturally, rather than being imposed.

4. Pan-Asianism in Japan

Nishida’s philosophy about the emperor seems not completely divorced from Pan-Asianism, one of the defining ideas of the modern world that informed the Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere. Born in Asia in the mid-19th century, Pan-Asianism called for unity among the peoples and nations in this vast region against Western imperialism, which overshadowed the entire Asia, from the Ottoman Empire to India to China. With the victory in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904, Japan emerged as the potential leader in Pan-Asianist movements. To rid Asia of Western imperialism, Pan-Asianists in Japan focused their attention on China under the Qing rule, a dysfunctional dynasty being targeted for colonization. Miyazaki Tōten, one of the leading figures of Pan-Asianism, for example, assisted Yun Yat-sen organize the Tongmenghui (同盟会) in Tokyo in 1905, which assisted Sun’s quest for Chinese revolution. Pan-Asianism, however, became a tool to justify Japanese imperialism from the 1920s onward. As the international tension over China, particularly Manchuria, intensified at the turn of the 1930s, Japanese Pan-Asianists clamored for expanding Japanese influence into the vast Eurasian continent to prepare for the impending war with the West. The invasion of China launched by the Kwantung Army in 1937 aligned with this line of thinking. As the war spilled over to Indochina in 1940, Japan’s troubled Pan-Asianism gained a global scope.

The clearest pronouncement of the new Pan-Asianism was made by Foreign Minister Matsuoka Yosuke, who had gained notoriety with his speech for Japan’s withdrawal from the League of Nations after the 1931 invasion of Manchuria. Matsuoka spoke about his vision about the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere at the 76th Session of the Imperial Diet on January 21, 1941. “Needless to say, the aim of Japan’s foreign policy is that of enabling all nations of the world each to take its own proper place, in accordance with the spirit of the Hakko Ichiu [八紘一宇 or ‘Eight Corners of the World under One Roof’], the very ideal which inspired the foundation of our Empire,”he claimed“We have thus maintained an attitude to surmount all obstacles for the purpose of establishing a sphere of co-prosperity throughout greater East Asia with Japan, Manchukuo and China as its pivotal point [8].” Matsuoka wrapped up Pan-Asianism and imperialism in the ideal of the Co-Prosperity Sphere, and countless individuals outside the government, including intellectual, latched on to this vision.

In “The New China I Saw” (見てきた新支那), Ichikawa Fusae, a prominent woman activist who attempted to improve the social status of women in wartime Japan by cooperating with the militarist government, visited Nanjing under Wang Jingwei, a puppet leader supported by Japan, after the infamous massacre in that city. “Whether the new government in fact has the sufficient ability to rule or, and this is a key point, whether Japan will fully support it is yet to be determined,” Ichikawa wrote “On this point, I have high hopes, plus it must succeed. The people in government have vitality, so there are some grounds for optimism.” “It is essential that Japanese women take the lead” to connect with Chinese women, she further maintained. “When military power is withdrawn, we must not end up back where we started. Rather, Japanese must set down roots culturally and work in concert based on a heartfelt respect of each individual for each other [8].” Ichikawa, in essence, offer an apology for Japanese imperialism in the name of international feminist solidarity.

In “Education for Japanese Capable of Being Leaders of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” (大東亜共栄圏の指導者たるべき日本人の教育), Yasuoka Masahiro, a conservative scholar of Eastern philosophy, discussed the problem of race in the Japanese empire, which was now expanding into the territories of what he considered inferior races: “It goes without saying that we must maintain racial purity and, as the word Yamato (大和) indicates, advance without losing Japan’s racial harmony. The more the Japanese state expands and the more it brings in numerous races, [the more we] must think seriously about how to simultaneously preserve the purity of the Japanese while realizing harmony with these various peoples and, furthermore, how to sustain the authority necessary to be the leader of these various ethnic and racial groups.” Not unlike the Western notion of Yellow Peril—the idea that Asians would bring calamity to the Western world—Yasuoka warned against the danger that racial impurity could bring to the Japanese empire. “Simply celebrating expansion and the fact of ruling many people is exceedingly childish and shallow. Indeed, I think it is clear that, for Japan’s sake, Japanese statesmen and intellectuals must exercise great vigilance in regard to the undesirable omens that are appearing everywhere [8].”

In “The Historical Basis of Greater Asianism” (大アジア主義の歴史的基礎), Hirano Yoshitaro, a Marxist historian of China who underwent “conversion” (転向) in 1936 and supported the militarist government, glorified the Co-Prosperity Sphere as Japan’s attempt to liberate Asia from the scourge of Western imperialism: “The national liberation movement that is bringing these various Asian peoples together and creating the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Community under the banner of Greater Asianism now constitutes a great menace to our enemies, Britain and America. In contrast to those who prostrate themselves before America, Britain and Russia, Japan’s construction of a Greater East Asia represents a genuine emancipation of Greater East Asia by Asians, for Asians. For this reason, we must smash the Anglo-Saxon invasion of the Orient as well as Russia’s intrigues [8].” Hirano’s argument, as flawed as it is, still resonates among nationalist groups in Japan today.

5. The Principle of the New World Order

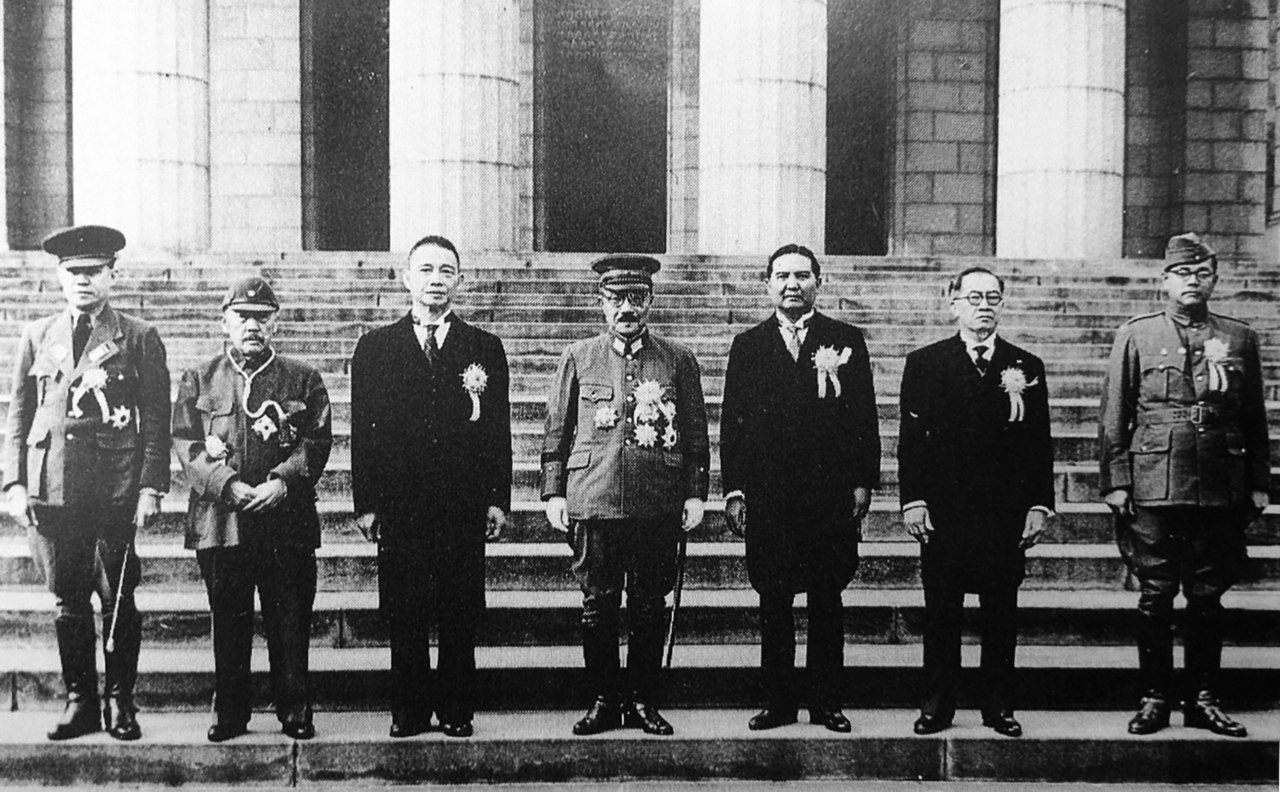

Nishida Kitaro’s “The Principle of the New World Order” came out of complex historical context. By 1943, the war in the Pacific had already become unwinnable for Japan, as the U.S. navy was taking back the chains of islands one by one. Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku, the man behind Pearl Harbor, was also killed in combat that April, due to a security breach in the communication system. Public support for the war was dwindling, although few spoke out against it in public. Desperate to revamp the war vigor at home and abroad, the military decided to set the Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere officially as Japan’s war aim. Prime Minister Tojo Hideki scheduled the first, and last, Greater East Asia Conference in late 1943. Tojo needed to embellish the Co-Prosperity Sphere with a lofty political philosophy, and Sato Kenryo of the Army asked Nishida, the most prominent philosopher at the time, to draft a joint proclamation for the conference when he attended the Research Institute of National Policy (国策研究会), in which public intellectuals were gathered to discuss national issues during the war.

Nishida was infuriated by the idea that the military was mobilizing intellectuals to justify the war he never supported. He, however, eventually agreed to do as told, perhaps out of the fear of ultranationalist retaliation, or perhaps because he wanted to fix the military’s thinking—many intellectuals participated in various imperial projects to steer them from within, mostly to little avail [6]. Nishida believed that “a philosopher's mission is to grasp the historical problem of the given historic world.” He hoped to educate the military not about the exceptionalism of Japan, but about the world historic context in which Japan should situate itself and its vision for Pan-Asianism. In his letter to Watsuji Tetsuro, philosopher at Tokyo Imperial University, Nishida stated that “there is a universal dimension in the ‘Japanese Spirit’,” which he hoped Tojo would understand and incorporate into the Greater East Asia Conference’s proclamation. Nishida’s finished draft, however, was too complex and philosophical to be comprehended by non-experts. Tanabe Hajime, Nishida’s friend and another philosopher in the Kyoto School, offered to help revise the document as he interpreted it. Although Tanabe’s revision made the text more closely aligned with the military’s thinking, many parts of the new draft were still esoteric, and Tanabe and the military also had communication issues over the drafting process. Nishida’s words, in the end, did not go into the proclamation or Tojo’s speech at the Greater East Asia Conference. In a letter to Watsuji, Nishida later expressed his disappointment with Tojo and the military for failing to understand his ideas.

The text of “The Principle of the New World Order”that is available now is the second draft with revisions added by Tanabe [9]. The first part of the text discusses world history, focusing on the rise of “global world” (世界的世界). According to the text, the 18th century was an “era of individual consciousness” (個人的自覚の時代) and the 19th century an “era of national consciousness”(国家的自覚の時代), to which belong such ideas as imperialism, colonialism, and communism. The 20th century, it argued, was an “era of global consciousness” (世界的自覚の時代). “Each nation should develop its unique tradition in accordance with its heritage and tradition, but at the same time, it should transcend itself in order to form a global unity,”an idea compatible with the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. The text nonetheless clearly differentiates its vision and a hegemonic conquest of the world—each nation should comprise the global world while maintaining its own existence and its own history and culture. This section seems to be solely written by Nishida, since it corresponds with his philosophical concept of “One and Many”(一と多). Nishida explained that each country can maintain its independence and uniqueness even inside a larger unity, without having to seek complete uniformity.

Nishida’s personality fades away as the text shifted its attention to the imperial system. It states that the morality in the world was no longer based on Chris tian altruism or the Confucius concept of the “Way of the King” (王道); instead, it should be constructed by nations transcending themselves to form a unified “global world.” The Japanese emperor should take the lead. “Our nation’s Imperial Way [皇道] contains the principle of world formation, that is, the principle of ‘Eight Corners of the World under One Roof’,” the text averred. It emphasized that this principle was different from Western imperialism. “What we should denounce in British and American thought is their imperialism and sense of superiority that view East Asia as colonies. Our nation’s policy… must avoid partisan totalitarianism,”the text continued. “Instead, it must base itself on the fair and righteous Imperial Way and its notions of ‘oneness of the emperor and his people’ [君民一体] and ‘All people assisting the emperor’[万民翼賛].”These lines of words seemed to demarcate the narrow space in which the visions of Nishida and the military could barely coexist.

Nishida’s personality comes back in the next section. The text states that in the Co-Prosperity Sphere, “the people that would be the central force must be generated historically and not chosen abstractly,”lest it would fall into “ethno-egocentrism” (民族自己主義), akin to U.S. and British imperialism. It argues that the League of Nations failed to achieve a “global world”because a few European countries elected themselves to be the governors of the interwar world by imposing their will on colonial subjects. Japan should not repeat the same mistake. “The Japanese have their own unique moral mission and responsibility as Japanese, given the historical reality of Japan, that is, within the current state of affairs,” the text reads, but they should not “select” themselves as the leader of the Co-Prosperity Sphere. Their role “must be born out of the formative principle of the global world.” By deploying the concept of a “global world,” Nishida seemed to be walking on a fine line between criticizing Western imperialism and legitimizing Japanese imperialism.

Japan’s religious and historical exceptionalism was in full swing in the last section of the text, however. “Japan is a divine country and its national polity is unlike that of any other nation abroad; it contains absolute historical globality,” the text proclaimed. With numerous political jargons, the text enshrined the divine rule of the empire at home and “Eight Corners of the World under One Roof” abroad as the dual principle of the “global world,” a better alternative to Western imperialism. “It is fair to say that the principle of our national polity can provide the solution to today’s world-historical problems,” the text concluded with the confidence that Japan would eventually emerge as the leader of the whole world, not just Asia. “No only should the Anglo-American world submit to it, but the Axis powers too will follow it.”

Nishida Kitaro’s “The Principle of the New World Order” never made its way into Tojo’s thinking as intended. Its flawed logic, as well as the military’s unwillingness to listen to any line of argument diverging from the official line, turned the document into a text that had no visible impact on politics. Tojo’s speech at the Greater East Asia Conference, in which the prime minister unabashedly defended the Pacific War as a “holy war” to liberate Asia from Western imperialism, bore many resemblances to “The Principle of the New World Order,” because Nishida’s text also borrowed from the same rhetoric. The Joint Declaration of the Greater East Asia Conference denounced the “insatiable aggression and exploitation” of U.S. and British imperialism in Asia and justified the war as an attempt at “liberating the region from the yoke of British-American domination.” It also promised to “ensure the fraternity of nations” by “by respecting one another’s traditions and developing the creative faculties of each race”—despite the oppressive policy Japan implemented in its colonies. Tojo’s words were a far cry from Nishida’s vision for the “new world order.”

Figure 2: Group Photo from Hideki Tojo's Speech Event.

As already mentioned, “The Principle of the New World Order” was a text full of contradictions, some of them arising from Nishida’s own thinking, others from the historical background against which it was written. Many parts of the text seem to reflect Tanabe’s views better than Nishida’s. The complex nature of “The Principle of the New World Order”is writ large to anyone who has read the anthology of Nishida’s works (全集)—it is clearly different from his other works in terms of style, language, and structure. This article analyze the two major contradictions in the text below and answer several questions about Nishida arising from the text.

The first major contradiction is political. His worldview, articulated in the first section of the text, can be encapsulated in the coexistence of localism and universalism. Unlike imperialism and colonialism, which denied the agency of smaller nations, he advocates a unity of nations in which each nation should transcend itself and sustain the whole, while being able to retain its history and tradition. The text makes a sharp logical turn from there—uncharacteristic of Nishida given the delicate logical construction in his other works—when it suddenly introduces the notion of the Imperial Way. Contradicting himself in the first section of the same text, Nishida, the purported author, underlines the superiority of the emperor, with the imperial jargon “Eight Corners of the World under One Roof,” which he never defined in this text or others. This is also uncharacteristic of Nishida, as he left few jargons unexplained in his anthology. The imperial logic of the text affords Japan the right to be the sole ruler of the world, a justification for Japanese imperialism, which Nishida is documented to have opposed in private.

The second major contradiction is religious. The term “Eight Corners of the World under One Roof,” a Nichiren-shu term invented in 1915, conformed to the Buddhist ideal of unity in the world, an ideal abused by the military. Trained in Zen Buddhism, Nishida’s use of “Eight Corners of the World under One Roof” to justify imperial deity might not seem completely illogical, but as explained above, he had rarely used the term, not to mention defined it, in any of his works. In his writings about religion, Nishida seemed to place more emphasis on Christianity than on Buddhism—he built his religious philosophy on the foundation of the notion of God as the creator of humans. This is not surprising, given that God was one of the key elements in Western philosophy, which he studied extensively. If Nishida was supportive of the empire, he could have used the concept of the holy duality that he entertained, that is, the emperor is the human form of God, an idea that most of the Japanese people subscribed to during the war. “The Principle of the New World Order,” however, is completely free of any positive reference to Christianity, a stark contrast to Nishida’s previous works.

These contradictions in “The Principle of the New World Order” raise questions about the text, Nishida Kitaro, and his role in Japanese imperialism. The first question is: How much did the text reflect and contradict Nishida’s thinking? The first section about world history conforms to Nishida’s own historical telling in his anthology, but the discussion on the Imperial Way might be added by Natabe, who hoped to make the text more savory to the military. The religious components in the text, especially the uncritical use of “Eight Corners of the World under One Roof,” also contradicted Nishida’s lifelong attempt to combine Western and Eastern philosophy to analyze the world, another piece of evidence that Tanabe revised the original draft to make it more politically acceptable. “The Principle of the New World Order,” as a result, became a patchwork of Nishida’s thought and the official line sanctioned by the government, a combination that made the text lacking logic overall.

The second questions is: Did Nishida support the Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere? Despite Nishida’s enmity toward the military, his philosophy and the Co-Prosperity Sphere had some common ground—both were based on the concept of “global unity.” Yet the lone philosopher never quite articulated this concept as a political subject. One would have the overwhelming impression from the vast body of his work that Nishida, first and foremost, was a philosopher without much interest in applying his theories to the reality; his logic and reasoning mostly remain in the realm of metaphysics and epistemology. Tosaka Jun, former student of Nishida’s who turned Marxist, criticized Nishida’s philosophy, as well as Tanabe’s, as capitalist idealism, detached from historical materialism. In his correspondence, Nishida implied that his tepid brush with politics was motivated by critics like Tasaka [9]. His engagement with real-world politics ended in frustration. Disappointed with the military’s inability to understand his philosophical thinking, Nishida reportedly revised Tanabe’s draft again, although the final text was not currently available. Despite some similarities on the surface, Nishida’s philosophy, therefore, was incompatible with the premises of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Finally, was Nishida an imperial collaborator? Countless Japanese intellectual chose to cooperate with the government to secure their lives in the 1930s and 1940s, lest they faced the danger of prosecution, imprisonment, and torture. Nishida, and numerous other intellectuals, decided to do the same, yet with the hope that by interacting with the government, they might be able to steer its policy from within. It turned out to be a forlorn hope, for after all, it was the military that was mobilizing intellectuals like Nishida for its own agendas, not the other way around. Not only did Nishida fail to convey his thought to the Tojo government, he also put himself in a precarious moral position by agreeing to write “The Principle of the New World Order.” Japanese imperialism had internalized Nishida and countless others like him. After Nishida’s death and the end of WWII, Tanabe withdrew himself into self-seclusion, agonizing over his role in the disastrous war. If Nishida had lived to see how the war ended, he might have done the same.

6. Conclusion

On August 15, 1945—about two months after Nishida’s death on June 7—Japan accepted an unconditional surrender, and World War II ended. In response to the government suppression and censorship in the 1930s and 1940s, Japanese intellectuals, many of them leftists sympathetic to Marxism, mounted a fierce offensive against intellectuals who cooperated with the government during the war, including Nishida. In a 1954 article titled “The Defeat of Nishida Kitaro” in Bungeishunju, Oya Soichi, a communist writer, accused Nishida of being a wartime collaborator, who compromised his moral principle as a leading philosopher and wrote “The Principle of the New World Order” for the military, an essay that seemed to justify Japanese imperialism in Asia. Nishida’s disciples in the Kyoto School shot back. Using Nishida’s personal papers, they argued that Nishida, as well as other philosophers in the Kyoto School, never advocated Japanese imperialism. Ohashi Ryosuke, one of the leading philosophers in postwar Japan, described Nishida and other Kyoto School philosophers as committed to “resistance within the system” (体制内の反体制), that is, they tried to change Japan’s ideas and actions by advising the government against imperialism [10]. If they tried to do so, however, they clearly failed to achieve their goals.

Nishida Kitaro’s “The Principle of the New World Order” sheds a unique light on the crossroad of Japanese philosophy and Japanese imperialism. Scholars of Japanese philosophy usually dismiss “The Principle of the New World Order” as little to do with his scholarly work, while historians of Imperial Japan would criticize the imperialist quality of the essay without heeding Nishida’s philosophy. One needs to use both the philosophical and historical lenses to understand the nature of the text. A bookish philosopher caught up in a testing time, Nishida serves as evidence that some intellectuals, who had been spared in the tense political climate during the total war, resisted, though passively, the militarist government by trying to influence its policy from within. The text was a result of the compromise between his philosophical worldview and the political necessity at the time. Despite Nishida’s effort, the Japanese empire—so unwieldy that Hirohito had to intervene personally to accept the surrender even after Hiroshima and Nagasaki—only doubled down on its imperialist Pan-Asianism. Yet “The Principle of the New World Order” demonstrates that the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere was not a monolithic ideology—it was a space in which intellectuals like Nishida could negotiate their visions for the world.

References

[1]. Barnhart, M. A. (2013). Japan prepares for total war: The search for economic security, 1919–1941. Cornell University Press.

[2]. Young, L. (1998). Japan's total empire: Manchuria and the culture of wartime imperialism (Vol. 8). Univ of California Press.

[3]. Yellen, J. A. (2019). The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere: When Total Empire Met Total War. Cornell University Press.

[4]. Ukai, H. (2022). Buddhism and the Great East Asia War. Bunshun Shinsho.

[5]. Hiroshi, H., Nobukuni, Y., Kenichi, M., Hisao, M., Chikara, S., Keiichi, N., & Fumishi, S. (1998). Iwanami Dictionary of Philosophy and Thought. Iwanami Shoten. pp. 1908-1909.

[6]. Yusa, M. (1991). Nishida and the Question of Nationalism. Monumenta Nipponica, 46(2), 203-209.

[7]. Iwano, Takuji. (2019). The Possibility of the 'Imperial Household' as Nothingness: One Aspect of Kitaro Nishida's Political Philosophy. Meiji University Liberal Arts Review, 540, 1-14.

[8]. Saaler, S., & Szpilman, C. W. (Eds.). (2011). Pan-Asianism: A Documentary History, 1920–Present (Vol. 2). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

[9]. Arisaka, Y., & Kitarô, N. (1996). The Nishida Enigma:The Principle of the New World Order'. Monumenta Nipponica, 51(1), 81-105.

[10]. Yamaguchi, S. (2020). Intellect and Regret: On Kitaro Nishida and the Kyoto School's Cooperation with the War Effort. Collection of Literature Research Studies, 52, 79-98.

Cite this article

Guo,Z. (2024). Nishida Kitaro and Japan’s Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,38,66-76.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Barnhart, M. A. (2013). Japan prepares for total war: The search for economic security, 1919–1941. Cornell University Press.

[2]. Young, L. (1998). Japan's total empire: Manchuria and the culture of wartime imperialism (Vol. 8). Univ of California Press.

[3]. Yellen, J. A. (2019). The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere: When Total Empire Met Total War. Cornell University Press.

[4]. Ukai, H. (2022). Buddhism and the Great East Asia War. Bunshun Shinsho.

[5]. Hiroshi, H., Nobukuni, Y., Kenichi, M., Hisao, M., Chikara, S., Keiichi, N., & Fumishi, S. (1998). Iwanami Dictionary of Philosophy and Thought. Iwanami Shoten. pp. 1908-1909.

[6]. Yusa, M. (1991). Nishida and the Question of Nationalism. Monumenta Nipponica, 46(2), 203-209.

[7]. Iwano, Takuji. (2019). The Possibility of the 'Imperial Household' as Nothingness: One Aspect of Kitaro Nishida's Political Philosophy. Meiji University Liberal Arts Review, 540, 1-14.

[8]. Saaler, S., & Szpilman, C. W. (Eds.). (2011). Pan-Asianism: A Documentary History, 1920–Present (Vol. 2). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

[9]. Arisaka, Y., & Kitarô, N. (1996). The Nishida Enigma:The Principle of the New World Order'. Monumenta Nipponica, 51(1), 81-105.

[10]. Yamaguchi, S. (2020). Intellect and Regret: On Kitaro Nishida and the Kyoto School's Cooperation with the War Effort. Collection of Literature Research Studies, 52, 79-98.