1. Introduction

Child labor has been a subject of widespread international concern, yet not all work done by children is referred to as child labor. According to the definition of the International Labor Organization(ILO), child labor refers to work that violates the rights of children and exposes them to physical and mental harm in various ways. It is shocking that more than 200 million children are now becoming adopted and more than half are engaged in hazardous work[1]. This large number implies that the number of children being exploited and oppressed by the labor force today is very high, and that more attention should be devoted to the protection of child labor rights.

This paper uses Merton's anomie theory to provide a macroscopic interpretation of the emergence of child labor, describe the hazards of child labor from both physical and psychological perspectives, and describe the roles of both educational and economic factors in child labor. These results will provide a better understanding of child labor in educational and economic terms, and address child labor issues. The author also combines these two factors to make recommendations to relevant governments and organizations. Since there has been much evidence in literature exploring the roles that economics and education play in child labor separately, there is less statements that refers to economics and education as either contributing to or inhibiting each other in child labor. The paper aims to contribute to the reduction of child labor by analyzing these two factors and finding out how their combination affects child labor rates.

2. Formation of child laborers

This paper utilizes Merton's theory of anomie as the main lens through which child labor is interpreted as a manifestation and approach of society in the state of 'anomie'. Anomie refers to the phenomenon that occurs when cultural norms and goals become wildly out of sync with the behaviors of the members of a society[2].

In general social expectations, children are expected to be educated, to have legitimate rights and interests, and to develop to their full potential, yet in some societies, children's education is grossly under-resourced, and children are forced, for various reasons, to work to earn an income. In this situation, the child's ability to earn an income by engaging in unsuitable work becomes a reflection of the state of social anomie. In addition, children may be forced to engage in labor in order to make ends meet when the lack of family or social resources or social norms cannot provide for their needs, in which case anomie becomes a means of forcing children to lose the opportunity for normal growth. A study has shown that child labor is intergenerationally transmitted and that many parents who have experienced child labor still choose to send their children to work when they have the ability to choose not to let their children become child laborers[3]. This suggests that child labor has become the new 'social norm' among these populations.

It can be seen that poverty and education are the main factors leading to an imbalance in social goals and pathways, when there is a great deviation between the social goals that should be achieved and the distribution of resources in reality. The long hours of work and lack of education also cause irreversible harm to the physical and psychological well-being of children.

3. Health damage to children from participation in labor

Although not fully developed physically and psychologically, child labourers, as cheap substitutes for adult labor, are subjected to the same work pressure as adults and are often suppressed by capitalists, which undoubtedly takes a huge toll on their bodies and minds. Children are more vulnerable to social and psychological risks than adults. In the United States, for example, workers aged 15 to 17 are twice as likely as adults to be involved in accidents at work [4]. As a result, the physical and mental health of child workers is more vulnerable than that of their peers.

3.1. Physical health problems faced by child workers

Child laborers are often subjected to bullying, such as verbal abuse and mistreatment, at work, and the nature of their work makes them more vulnerable to harm at work because they are mostly working at the bottom. Child laborers in Myanmar reportedly risk their lives to pick up gemstones. In that dangerous environment, even adults can easily lose their lives[5]. In another case, a major restaurant chain in Mexico was found to have violated more than 13,000 child labor provisions, where child laborers worked after midnight and for more than 48 hours a week[6]. This exploits children's sleep time and is extremely harmful to adolescents during their developmental years.

Children who work in factories and mines operate machinery, handle chemicals, are exposed to high temperatures and extreme cold, and eventually die. In addition, children are used in life-threatening situations such as the sex industry, war, drug trafficking, and smuggling of soldiers. For those children who sell goods on the street, most of them carry the goods on their heads, and such heavy loads can negatively affect the growth of children, and accidents [7]. Besides, involving children in productive activities can lead to malnutrition and road traffic accidents, and those who work at high speeds are more likely to experience health complications than the average child[8].

3.2. Mental health issues facing child workers

Apart from physical illnesses, mental illnesses are also of great concern. Some child laborers are bought by capitalists and work as slaves, an environment that can make them more prone to low self-esteem, depression, etc. The survey of Laraqui et al. [9] in Morocco indicates that child laborers are more likely to suffer from migraines, urinary incontinence, insomnia and other physical ailments, as well as psychological emotional problems such as irritability. It is noteworthy that the prevalence of mental disorders in child labor is nearly 8% higher than in the general population [10] Thabet et al. [11] identified childhood work as increasing the chances of developing psychological disorders such as depression in adulthood.

Faced with a heavy workload that is beyond their capacity, child laborers are more likely to be overwhelmed with stress, which can lead to suicidal behaviors. It was reported that a spinning mill in India once led to the suicide of child laborers because of poor labor mediation and heavy work. There was also a boy who died as a result of continuous work for a USD40 bonus [12]. High-intensity work is also unbearable for the mental strength of adults, let alone child laborers as young as about ten years old.

4. Education of children engaged in productive activities

It is undeniable that in some areas where education levels are extremely low, exposing children to work at an earlier age can indeed bring certain benefits. According to the study Emerson and Souza [13] conducted in Brazil, child laborers receive greater rewards at work than educated children of the same age because they get more work experience. While working as a child may seem more cost-effective, their study also states that in the long-term, they will have a lower income in adulthood than those who were educated.A study points to a positive correlation between educational attainment and output per person, which indicates that raising the educational literacy of the population can do more to raise the overall level of national output than putting young children to work.

4.1. The current situation of child labor's education

Child labor has been a major obstacle to world development since the last century, and education is at the center of the solution to the problem of child labor[15]. One of the differences between child labor and other children is that most child laborers are not educated in schools, although some still choose to work and study half-time.

Despite the implementation of compulsory education or education subsidy policies in many areas, many children still drop out of school to engage in productive work. In Bangladesh, for example, only 29 percent of working children were attending school in 2013 [16], despite the country's legislation providing for five levels of compulsory education and a small monthly subsidy for children attending elementary school [17].

A child's gender can determine whether a family chooses to educate its children. In many developing countries, due to their culture, for many women, education is only available to them if there is a surplus of family assets. It is also mentioned in the article that in these places, due to discrimination against women, parents create a skew in resources and do what they do mainly for boys.

4.2. The relationship between education and child labor

The intensity of child labor activities can cause children to attend school infrequently or even drop out [18]. Thus, child labor activities have a negative impact on children's education both in terms of school enrollment and school performance [19].

Firstly, child labor phenomenon hinders local education development. As Zabaleta [14] demonstrated, child labor impedes educational development in Nicaragua. With the exception of full-time child laborers, some child laborers still have the opportunity to participate in education at school. However, working half-time means that they spend less time and energy doing homework and reviewing their knowledge than other students.

Besides, for the children themselves, school keeps them away from cruel rules and regulations, gives them the opportunity to meet and play with their peers, and allows them to develop in all aspects of their intellectual and moral development. An example of this is the study carried out by Githitho-Muriithi[20] , which shows the extreme enthusiasm of Kenyan children for education is on display, especially for children who have to become full-time child laborers and who are nostalgic for their school days because the school symbolizes peace and friends.

Otherwise, for those students in school, the extra work can cause their grades to plummet. Anumaka [21] previously conducted a study in the Anebbi district, northern Uganda, where she found that underperforming children were engaged in productive work through a survey of 2307 students who took their elementary school leaving exams. Another study conducted in Brazil also found that part-time child laborers had a ten percent lower performance than other students [22]. In terms of learning abilities (e.g., reading and math skills), according to Heady [23], there is also a negative relationship between child labor activities and academics.

Furthermore, the cost required to access education is positively correlated with the number of child laborers. It has already been mentioned that the economic situation of families who put their children to productive work is mostly poor. As Strulik [24] showed, the incidence of child labor remains high in low-income areas, which results in fewer children having access to education. The child labor population begins working earlier than their peers, which may seem to allow them more work experience, giving them a higher level of competence and, therefore a higher salary. However, the truth is child workers who start working at an excessively young age lack systematic knowledge acquisition, so they earn less in the future compared to their educated peers [25].

5. The impact of regional or household economies on child labor

Some studies have shown that economically shocked families are more likely to engage their children in productive activities as a way to earn more income in the short term[18; 26]. According to statistics, child labor has so far occurred mostly in areas of chronic economic poverty[27], from which it can be inferred that economic development may have some influence on this phenomenon. This shows that the lack of a family economy is an important factor in child labor.

Economic backwardness not only leads to a high incidence of child labor, but also hinders the enforcement of relevant laws. Child labor in Ecuador is often seen as exemplary, the implementation of child labor laws there is limited by the scarcity of local resources the backward economy in the region.

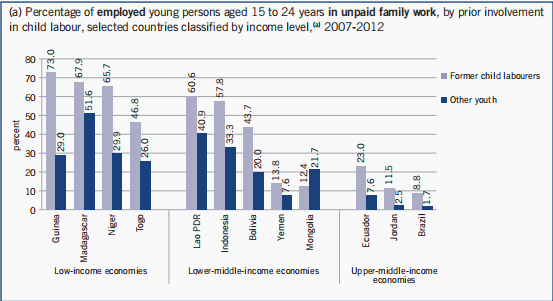

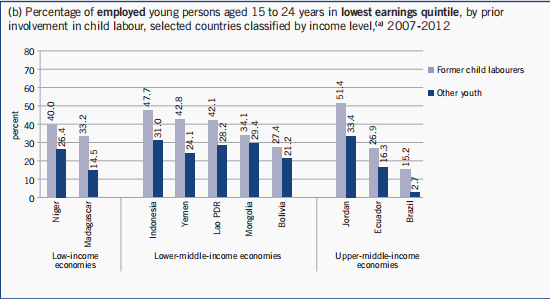

Figure 1: The situation of child workers and their families

Source: International Labour Organization(2015), Paving the way to decent work for young people, World report on child labour 2015

This bar chart analyzes the child labor situation in each of the twelve different countries between 2007 and 2012, using calculations from the National Household Survey. From the chart, it can be concluded that child workers are more likely to be satisfied with unpaid family work and receive lower salaries in adulthood. What can be clearly seen in this chart is the difference between large income gap between child labor and other young. It can be seen that perhaps the work experience of a child laborer may allow him to surpass his peers in the short term, but in the long run, child labor is not conducive to their physical and mental health and personal development.

Due to their young age and low knowledge, child laborers mainly play the role of cheap labor in economic production and are, therefore, mostly involved in low-skilled manual activities. International Labour Organization(ILO) [28] points out that child laborers are mainly recruited in the agricultural sector, where they are directly or indirectly concentrated in agriculture-related industries. This is mainly due to the lower level of mechanization and primitive production methods in economically backward areas of agriculture, which mostly use human labor. For capitalists, the use of child labor can pay less salary[29]. These areas also experience labor shortages during the busy agricultural season, when there is also a demand for child labor. This manifests an imbalance between demand and supply in the labor market, resulting in children being forced into the labor market to meet the needs of capitalists.

6. Measures Governments can take

According to Shah and Steinberg[30], adolescent males are more likely to work for pay, while adolescent females are more likely to perform hidden labor at home, which involves housework. For children who have to become child laborers because of poverty, people boycotting child labor products or issuing child labor bans may make life more difficult for them [31]. This shows that in order to solve the problem of child labor, it is necessary to address its root causes. In general, the government mostly encourages children to pursue education rather than productive work by increasing family income or reducing family education. This paper argues that child labor is caused by poverty, lack of social system and lack of values. Therefore the most crucial thing to alleviate child labor is to make families pay attention to children's education and increase family income.

6.1. Subsidies for children's education

The Government can alleviate the burden of children's education on families by granting education subsidies and encouraging children to engage in unproductive work that has a low impact on their health. The government provides educational subsidies or compulsory education for child laborers as a way to encourage children to go to school. For developing countries, extreme poverty is considered to be the main reason for the prevalence of child labor. It is widely known that the economy determines politics, so it can be deduced that the economic conditions of the government determine the strength of its policies. For example, in some areas of extreme poverty, even when the government is committed to providing compulsory education, the state cannot afford to make it nationwide [32]. According to Kenya National Bureau of Statistics [33], Kenya, whose government provides free primary education, still had approximately 1.01 million Kenyan children between the ages of five and seventeen who were working to support their families for economic reasons in 2005 and 2006. For such countries, international or non-governmental organizations should provide appropriate assistance. After Covid-19, online classes are gradually being embraced, and these organizations can provide pre-recorded lessons to the community so that children can learn at less cost.

6.2. Increase jobs or open up microfinance

In order to alleviate family poverty, the government can increase family income by increasing employment opportunities or opening up small loans. In order to eradicate poverty, developing countries undertake public work projects such as infrastructure improvement and construction as a way to provide basic income to the poor [34]. This project raises the demand for labor and therefore, in some cases, this may exacerbate children’s engagement in productive activities [35]. Although such cases are in the minority, it is still evident that child labor is sometimes inevitable when governments secure and develop their economies. The National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme introduced by the Indian government has increased the demand for adult labor. An Non-Governmental Organization(NGO) in Bangladesh tried an experiment in rural areas to provide training and microcredit to rural families, which substantially increased the income of these families. Unfortunately, despite the significant increase in household income, the working hours of child laborers did not decrease significantly [36]. Some of these policies have not only failed to alleviate the problem of child labor in the short term, but have even made the problem of child labor worse in the short term. However, in the long run, it has a positive side to child labor. The implementation of policies can subtly influence the values and rules that shape people's lives. As families ' incomes increase and the Engel coefficient decreases, the likelihood that children will receive an education increases.

Since child labor is not something that can be solved immediately, the government can also create jobs for children of different ages who need to earn money. As mentioned earlier, many children need an income to make ends meet, but child laborers face jobs that are mostly dangerous and illegal. Therefore, the Government can cooperate with enterprises or relevant welfare organizations to create targeted jobs for children in need.

7. Conclusion

Children are the future citizens of the country, and their full development is the country's top priority. In some underdeveloped or low economic areas, the lack of awareness of the inputs and benefits of labor, as well as the mismatch between productivity and production levels, have led to the exploitation of children as laborers because of the inadequacy of the local legal system, the inability of the government to enforce the law, and the distortion of people's values. Various causes of child labor have been identified around the world, but the main cause is poverty. The effects of child labor are many, but the psychological effects are the most enduring problem and require immediate attention, especially in third world countries where awareness is low. Governments need to formulate appropriate and concise laws and policies that not only ensure the protection of children, but also force parents to understand and comply with them. Besides, governments and responsible organizations around the world should make it easier for poor people to send their children to school and create social awareness about the children in engaged productive activities and their effects. Working children struggle with depression, mistrust, hopelessness, lack of confidence, shame and guilt, low self-esteem and anxiety, and can become adults who pose a risk to society. To build a better future and protect society, a series of coordinated actions are needed to reduce child labor.

The causes of child labor are complex and multifaceted, and many child workers are forced to participate in productive activities to earn a living due to various economic and other circumstances. Therefore, it is not advisable to ban child labor outright. To solve the problem of child labor, we need not only the support of governments, but also the concerted efforts of the whole world. Children are the future of the world and only by better protecting their rights and finding the root of the problem can more children be freed from exploitation.

References

[1]. The Word Counts. (2023). Child labor facts and statistics. The World Counts. https://www.theworldcounts.com/stories/Child-Labor-Facts-and-Statistics.

[2]. Faizi, I., & Nayebi, H. (2023). Anomie Theories of Durkheim and Merton: A Comparative Review. Comparative Sociology, 22(2), 280–297.

[3]. Katav Herz, S., & Epstein, G. S. (2022). Social norms and child labor. Review of Development Economics, 26(2), 627–638.

[4]. UNICEF. (2011). THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2011 Adolescence An Age of Opportunity. https://www.unicef.org/media/84876/file/SOWC-2011.pdf

[5]. UN News. (2021, January 29). FROM THE FIELD: The Myanmar child workers risking their lives for stones. UN News. https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/01/1082102.

[6]. News, A. B. C. (2020). Chipotle fined $1.3M over thousands of child labor abuses. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/US/wireStory/chipotle-fined-13m-thousands-child-labor-abuses-68575444.

[7]. Porter, G., Blaufuss, K., & Acheampong, F. (2011). Filling the family transport gap in sub–Saharan Africa: Young people and load carrying in Ghana. In L. Holt (Ed.). Geographies of children, youth and families. An international perspective. London: Routledge.

[8]. Hamenoo, E. S., Dwomoh, E. A., & Dako-Gyeke, M. (2018). Child labour in Ghana: Implications for children’s education and health. Children and Youth Services Review, 93, 248–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.07.026.

[9]. Laraqui,C.H. et al. , (2000). Child labour in the artisan sector of Morocco: Determinants and health effects, Sante Publique

[10]. Fekadu, D., Alem, A., & Hägglöf, B. (2006). The prevalence of mental health problems in Ethiopian child laborers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(9), 954–959. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01617.x.

[11]. Thabet, A. A., Matar, S., Carpintero, A., Bankart, J., & Vostanis, P. (2010). Mental health problems among labour children in the Gaza Strip. Child: Care, Health and Development, 37(1), 89–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01122.x.

[12]. Nagaraj, A. (2018, February 8). Suicide at Indian spinning mill sparks child labour investigation. U.S. https://www.reuters.com/article/india-textiles-children-idUSL4N1PX47R.

[13]. Emerson, P. M., & Souza, A. P. (2011). Is Child Labor Harmful? The Impact of Working Earlier in Life on Adult Earnings. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 59(2), 345–385. https://doi.org/10.1086/657125

[14]. Zabaleta, M. B. (2011). The impact of child labor on schooling outcomes in Nicaragua. Economics of Education Review, 30(6), 1527–1539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2011.08.008

[15]. International Labour Organization. (2021). Child labour and education (IPEC). International Labour Organization. https://www.ilo.org/ipec/Action/Education/lang--en/index.htm#banner

[16]. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. (2015). Bangladesh national child labour survey 2013. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. https://www.ilo.org/ipec/Informationresources/WCMS_IPEC_PUB_28175/lang--en/index.htm

[17]. Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. (2013). Elimination of child labor, protection of children and young persons. Legislative and Parliamentary Affairs.

[18]. Beegle, K., Dehejia, R., & Gatti, R. (2009). Why Should We Care About Child Labor? Journal of Human Resources, 44(4), 871–889. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.44.4.871

[19]. International COCA Initiative. (2007). Addressing child labour through education: A study of alternative/complementary initiatives in quality education delivery and their suitability for cocoa-farming communities | ICI Cocoa Initiative. Www.cocoainitiative.org. https://www.cocoainitiative.org/knowledge-hub/resources/addressing-child-labour-through-education-study-alternativecomplementary.

[20]. Githitho-Muriithi, A. (2010). Education for all and child labour in Kenya: A conflict of capabilities? Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(2), 4613–4621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.739

[21]. Anumaka, I. B. (2012). CHILD LABOUR: IMPACT ON ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE AND SOCIAL IMPLICATION: A CASE OF NORTHEAST UGANDA . Journal of Educational Science and Research, 2(2), 12–18.

[22]. Bezerra, M. E., Kassouf, A. L., & Arends-Kuenning, M. (2009). The Impact of Child Labor and School Quality on Academic Achievement in Brazil. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1369808.

[23]. Heady, C. (2003). The Effect of Child Labor on Learning Achievement. World Development, 31(2), 385–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(02)00186-9.

[24]. Strulik, H. (2004). Child Mortality, Child Labour and Economic Development. The Economic Journal, 114(497), 547–568. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2004.00231.x.

[25]. Posso, A. (2017). Child Labour’s effect on long-run earnings: An analysis of cohorts. Economic Modelling, 64, 465–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2017.02.027.

[26]. Dumas, C. (2006). Why do parents make their children work? A test of the poverty hypothesis in rural areas of Burkina Faso. Oxford Economic Papers, 59(2), 301–329. https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpl031.

[27]. Save the Chilren. (2021). GLOBAL CHILDHOOD REPORT 2020. Save the Chilren.

[28]. International Labour Organization. (2017). Global estimates of child labour: Results. International Labour Office, Geneva.

[29]. Gupta, M. R. (2000). Wage Determination of a Child Worker: A Theoretical Analysis. Review of Development Economics, 4(2), 219–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9361.00090.

[30]. Shah, M., & Steinberg, B. M. (2019). Workfare and Human Capital Investment: Evidence from India. Journal of Human Resources, 56(2), 1117-9201R2. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.56.2.1117-9201r2.

[31]. Basu, K., Van, P.H. (1998). The economics of child labor, The American Economic. 412-427.

[32]. Mankiw, N. G., Romer, D., & Weil, D. N. (1992). A Contribution to the Empirics of Economic Growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(2), 407–437. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118477

[33]. Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. (2008). Child Labour Analytical Report. Nairobi

[34]. Subbarao, K., Carlo del Ninno, Andrews, C., & Rodríguez-Alas, C. (2013). Public Works as a Safety Net: Design, Evidence, and Implementation. RePEc: Research Papers in Economics.

[35]. Dammert, A. C., de Hoop, J., Mvukiyehe, E., & Rosati, F. C. (2018). Effects of public policy on child labor: Current knowledge, gaps, and implications for program design. World Development, 110, 104–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.05.001.

[36]. Bandiera, O., Burgess, R., Das, N., Gulesci, S., Rasul, I., & Sulaiman, M. (2017). Labor Markets and Poverty in Village Economies*. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(2), 811–870. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjx003.

Cite this article

Cui,M. (2024). Restricted Child Development: Child Labor from an Economic and Educational Perspective. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,38,96-103.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. The Word Counts. (2023). Child labor facts and statistics. The World Counts. https://www.theworldcounts.com/stories/Child-Labor-Facts-and-Statistics.

[2]. Faizi, I., & Nayebi, H. (2023). Anomie Theories of Durkheim and Merton: A Comparative Review. Comparative Sociology, 22(2), 280–297.

[3]. Katav Herz, S., & Epstein, G. S. (2022). Social norms and child labor. Review of Development Economics, 26(2), 627–638.

[4]. UNICEF. (2011). THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2011 Adolescence An Age of Opportunity. https://www.unicef.org/media/84876/file/SOWC-2011.pdf

[5]. UN News. (2021, January 29). FROM THE FIELD: The Myanmar child workers risking their lives for stones. UN News. https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/01/1082102.

[6]. News, A. B. C. (2020). Chipotle fined $1.3M over thousands of child labor abuses. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/US/wireStory/chipotle-fined-13m-thousands-child-labor-abuses-68575444.

[7]. Porter, G., Blaufuss, K., & Acheampong, F. (2011). Filling the family transport gap in sub–Saharan Africa: Young people and load carrying in Ghana. In L. Holt (Ed.). Geographies of children, youth and families. An international perspective. London: Routledge.

[8]. Hamenoo, E. S., Dwomoh, E. A., & Dako-Gyeke, M. (2018). Child labour in Ghana: Implications for children’s education and health. Children and Youth Services Review, 93, 248–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.07.026.

[9]. Laraqui,C.H. et al. , (2000). Child labour in the artisan sector of Morocco: Determinants and health effects, Sante Publique

[10]. Fekadu, D., Alem, A., & Hägglöf, B. (2006). The prevalence of mental health problems in Ethiopian child laborers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(9), 954–959. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01617.x.

[11]. Thabet, A. A., Matar, S., Carpintero, A., Bankart, J., & Vostanis, P. (2010). Mental health problems among labour children in the Gaza Strip. Child: Care, Health and Development, 37(1), 89–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01122.x.

[12]. Nagaraj, A. (2018, February 8). Suicide at Indian spinning mill sparks child labour investigation. U.S. https://www.reuters.com/article/india-textiles-children-idUSL4N1PX47R.

[13]. Emerson, P. M., & Souza, A. P. (2011). Is Child Labor Harmful? The Impact of Working Earlier in Life on Adult Earnings. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 59(2), 345–385. https://doi.org/10.1086/657125

[14]. Zabaleta, M. B. (2011). The impact of child labor on schooling outcomes in Nicaragua. Economics of Education Review, 30(6), 1527–1539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2011.08.008

[15]. International Labour Organization. (2021). Child labour and education (IPEC). International Labour Organization. https://www.ilo.org/ipec/Action/Education/lang--en/index.htm#banner

[16]. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. (2015). Bangladesh national child labour survey 2013. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. https://www.ilo.org/ipec/Informationresources/WCMS_IPEC_PUB_28175/lang--en/index.htm

[17]. Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. (2013). Elimination of child labor, protection of children and young persons. Legislative and Parliamentary Affairs.

[18]. Beegle, K., Dehejia, R., & Gatti, R. (2009). Why Should We Care About Child Labor? Journal of Human Resources, 44(4), 871–889. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.44.4.871

[19]. International COCA Initiative. (2007). Addressing child labour through education: A study of alternative/complementary initiatives in quality education delivery and their suitability for cocoa-farming communities | ICI Cocoa Initiative. Www.cocoainitiative.org. https://www.cocoainitiative.org/knowledge-hub/resources/addressing-child-labour-through-education-study-alternativecomplementary.

[20]. Githitho-Muriithi, A. (2010). Education for all and child labour in Kenya: A conflict of capabilities? Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(2), 4613–4621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.739

[21]. Anumaka, I. B. (2012). CHILD LABOUR: IMPACT ON ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE AND SOCIAL IMPLICATION: A CASE OF NORTHEAST UGANDA . Journal of Educational Science and Research, 2(2), 12–18.

[22]. Bezerra, M. E., Kassouf, A. L., & Arends-Kuenning, M. (2009). The Impact of Child Labor and School Quality on Academic Achievement in Brazil. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1369808.

[23]. Heady, C. (2003). The Effect of Child Labor on Learning Achievement. World Development, 31(2), 385–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(02)00186-9.

[24]. Strulik, H. (2004). Child Mortality, Child Labour and Economic Development. The Economic Journal, 114(497), 547–568. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2004.00231.x.

[25]. Posso, A. (2017). Child Labour’s effect on long-run earnings: An analysis of cohorts. Economic Modelling, 64, 465–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2017.02.027.

[26]. Dumas, C. (2006). Why do parents make their children work? A test of the poverty hypothesis in rural areas of Burkina Faso. Oxford Economic Papers, 59(2), 301–329. https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpl031.

[27]. Save the Chilren. (2021). GLOBAL CHILDHOOD REPORT 2020. Save the Chilren.

[28]. International Labour Organization. (2017). Global estimates of child labour: Results. International Labour Office, Geneva.

[29]. Gupta, M. R. (2000). Wage Determination of a Child Worker: A Theoretical Analysis. Review of Development Economics, 4(2), 219–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9361.00090.

[30]. Shah, M., & Steinberg, B. M. (2019). Workfare and Human Capital Investment: Evidence from India. Journal of Human Resources, 56(2), 1117-9201R2. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.56.2.1117-9201r2.

[31]. Basu, K., Van, P.H. (1998). The economics of child labor, The American Economic. 412-427.

[32]. Mankiw, N. G., Romer, D., & Weil, D. N. (1992). A Contribution to the Empirics of Economic Growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(2), 407–437. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118477

[33]. Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. (2008). Child Labour Analytical Report. Nairobi

[34]. Subbarao, K., Carlo del Ninno, Andrews, C., & Rodríguez-Alas, C. (2013). Public Works as a Safety Net: Design, Evidence, and Implementation. RePEc: Research Papers in Economics.

[35]. Dammert, A. C., de Hoop, J., Mvukiyehe, E., & Rosati, F. C. (2018). Effects of public policy on child labor: Current knowledge, gaps, and implications for program design. World Development, 110, 104–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.05.001.

[36]. Bandiera, O., Burgess, R., Das, N., Gulesci, S., Rasul, I., & Sulaiman, M. (2017). Labor Markets and Poverty in Village Economies*. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(2), 811–870. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjx003.