1. Introduction

Social exclusion or Ostracism can be defined as being excluded or isolated by others, sometimes with an explicit declaration of dislike and sometimes not [1]. Usually, social exclusion involves being ignored and rejected by individuals or groups after interacting and separating [2], and this kind of behaviour commonly occurs in all social creatures and across human history. However, the desire for a stable and positive social bond is one of an individual's most fundamental and universal needs, and it is the need to belong [3]. Although the need to belong as one of the basic motivations for human existence lasted for decades in psychology, it was only over 25 years that social exclusion and ostracism became the topic studied in social psychology [4]. Maner et al. [5] found that when social exclusion happens, an individual might suffer from various ill effects on health and personal development. Social pain caused by social exclusion is an emotional distress sign that could activate the brain's neurological response, emphasising the necessity of forming a social connection for human survival [6]. Besides the physical effect of social exclusion, Meltzer et al. [7] reported that social exclusion has a solid relevance to mental illness, including social anxiety disorder (SAD).

SAD, or Social Phobia, is the third most common mental problem in adults worldwide. Its mild symptom would be the short-term social apprehension to respond to the social evaluation situation. The severe symptoms of SAD could be disabling, pervasive fear, and avoidance [8]. SAD is not easy to be realized by the individual, even for those individuals with a high level of self-focus. A global study about adolescents reports that 50 percent of them could recognize depression; however, only 2 percent realize the SAD [9]. Besides, adolescence is a period when SAD would first occur in individuals lives, and once it appears, it remains stable throughout individuals’ lifespan if without treatment [10]. SAD might be maintained and enforced by the interaction between an individual's self and their social situation. According to Wells [11], the anxiety of social situations would be maintained by a negative feedback loop, which consists of lower self-expectations, anxiety about anticipates, impaired cognition, and poor social performance and then be reinforced by the negative self-beliefs. People cannot see exactly what they are from others' views and tend to use their views about themselves as others' [12]. Individuals with a negative self might behave shyly through their impression of imagining satisfying their negative public self, which relates to poor social performance.

There are significant gaps in the understanding of social exclusion and SAD. Relationships between social exclusion and other mental illnesses, for example, depression, cognition and dementia, and elder mental health [13-15], have been frequently studied. Although SAD is the most common anxiety disorder [16], the morbidity effects of SAD are less understood, let alone its relationship with social exclusion.

2. The temporal need-threat model of ostracism

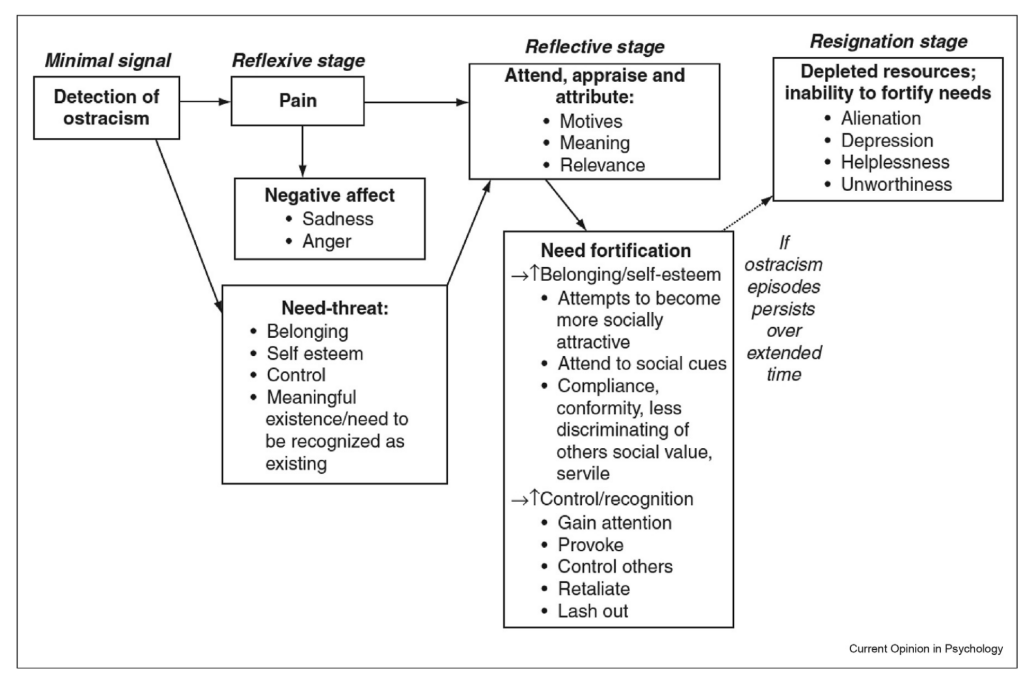

The temporal need-threat model of ostracism is one of the fundamental theoretical frameworks used for social exclusion research, proposed by Williams [17]. According to this model, there are three stages for individuals to react to social exclusion: the first stage is an immediate reaction to ostracism, reflexive; the second stage is reflective; in this stage, individuals need fortification to protect themselves from social exclusion, and when social exclusion becomes a long-term situation for individuals, they might suffer from resignation stage (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Williams’s temporal need-threat model of ostracism.

2.1. Minimal signal to detect social exclusion

When social exclusion happens, individuals only need a few signals to detect it [17], even if they do not hear or see it directly. Besides, they feel excluded even by no human creatures, for example, they are excluded when they play games with computers [18] and are negatively affected by ostracism. Furthermore, individuals might feel displeasure and detect social exclusion even when they have been told in advance that they might not be involved or just observe other people be excluded [19-21]. It seems that individuals could be quick and sensitive to detect social exclusion around them and unavoidably affected by it. Haselton and Buss [22] suggest that this might be because of the evolutionarily adaptive of human creatures, and the detection of social exclusion could be a kind of self-serving. It is better than not detecting, as missing the signal of ostracism could be fatal for social animals.

2.2. Reflexive stage

The immediate pain and negative feeling caused by social exclusion is not just based on individuals' self-reporting about how they feel when excluded. Eisenberger et al. [19, 6] report that when social exclusion happens, activation is detected in the brain area (the anterior cingulate cortex), typically activated when individuals are in physical pain. These areas' activation level correlates with individuals' reports of distress. Beyond the immediate physical and mental effect of social exclusion, Williams’s model also suggests that ostracism could threaten four fundamental psychological needs: belonging, self-esteem, control and meaningful existence.

One of the most important motivations for the individual to join a group is to satisfy their need to belong. Baumeister and Leary [3] proposed that "human beings have a pervasive drive to form and maintain at least a minimum quantity of lasting, positive, and significant interpersonal relationships". Self-esteem is subsumed by belonging [23]. When exclusion happens, there is a feeling of belonging loss, which could lower self-esteem [17]. Williams and Nida [4] suggest that social connections are associated with belonging and self-esteem.

Self-esteem is an individual’s feelings and evaluations about themselves. With high self-esteem, they have a clear and stable sense of themselves and focus on enhancing themselves. However, people with low self-esteem have less clear self-concept and aim to protect themselves [24]. Self-esteem could affect not only an individual’s feelings about themselves but also other people's feelings about them. Self-esteem could be a ‘sociometer’; through self-esteem, individuals could monitor other’s reactions and warn individuals of the potential possibility of social exclusion [23]. Furthermore, the pursuit of self-esteem is a part of human beings, assisting individuals to regularise their behaviour and cope with the existential situation [25]. Greenberg et al. [26] suggest that self-esteem is a buffer to maintain an individual’s meaningful existence.

2.3. Reflective

After the ostracism, individuals start reflecting on this experience, they might assess, appraise, and attribute the meaning and relevance of this painful episode, and because social exclusion threats their basic needs, they will be motivated to do something to re-establish their basic needs until it back to the optimal level [17]. However, individual differences, especially social anxiety levels, could affect the recovery speed after a brief ostracism episode.

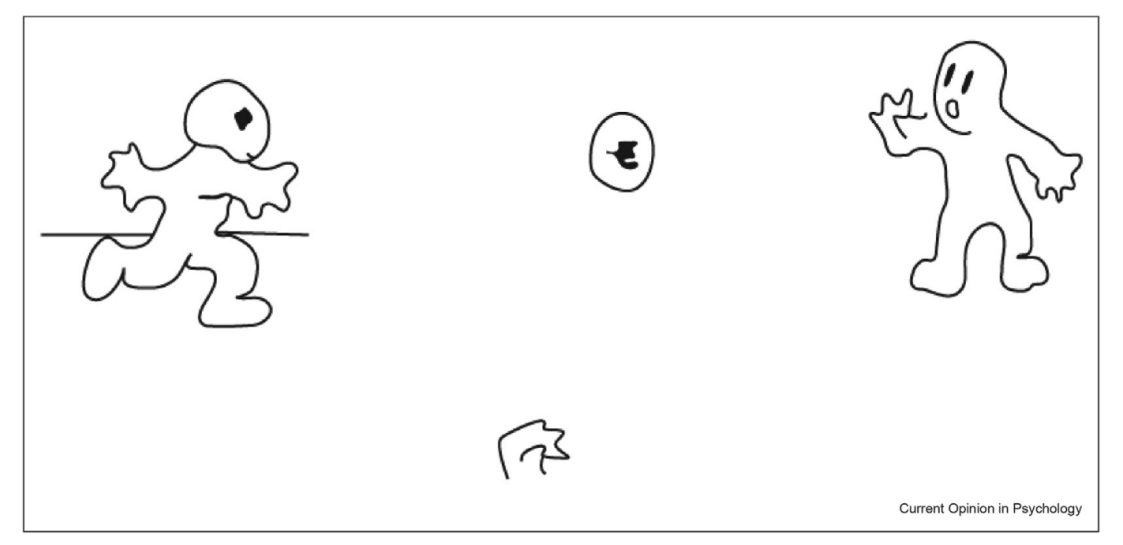

Through playing Cyberball (see figure 2) and measuring the after-game immediate need satisfaction and mood, Zadro et al. [27] found that both high and low social anxiety participants report distress during the immediate or reflexive stage. After a 45-minute work period, the individual with an average level of social anxiety could completely recover from this social exclusion experience. However, it is only halfway for high social anxiety individuals to recover from this exclusion experience. Furthermore, individuals with higher social anxiety levels or more sensitivity to rejection reflect more problems with self-regulation after social exclusion and inclusion [28-29].

2.4. Higher social anxiety inhibits the need repair

Fung and Alden [30] show that the intensity of social pain after the initial social exclusion could mediate the anxiety level of participants who experience subsequent social interaction. For individuals with higher social anxiety, their social repair is less than average social anxiety level individual after social exclusion, suggesting they might be less functional to release the negative effect of social pain, have a higher possibility to carry more weight of their past painful social event [31]. These effects could elevate and maintain the higher level of social anxiety and keep susceptible individuals more vulnerable within social situations.

According to the need-fortification hypothesis, individuals who experience social exclusion should feel, think and act to fortify their most threatened need(s) [17]. Recent studies have exhibited that excluded individuals usually behave more pro-socially and prefer to be affiliated [32,33] when social exclusion threatens their belongness or self-esteem. For example, they are more generous in sharing resources [34,35] and more motivated toward possible future social connections [36]. Prosocial behaviour helps them to re-establish those threatened belongingness needs and self-esteem. However, compared with average-level individuals, individuals with higher social anxiety prefer to avoid affiliation. They tend to protect themselves by socially withdrawing [37]. Hudd [38] explained that the reaction of high social anxiety individuals might be because they are more sensitive to threats (e.g., excessive attention and responsivity to threat signals), and this overactive threat-avoidance motivation system could drive their behaviour within interpersonal situations. Besides, there are fewer rewards for high social anxiety individuals to reconnect to others. Although some high social anxiety individuals display prosocial behaviour after being excluded, DeWall et al. [39] found that their attitude remains hostile. Hudd [40] suggests that the prosocial behaviour of excluded high social anxiety individuals might be because they want to avoid the potential social conflict rather than because of their desire to reconnect with others.

Oversensitivity toward social situations inhibits high social anxiety individuals from recovering from social exclusion and their fortification desire toward re-establishing their basic needs. It is a challenge for high social anxiety individuals to deal with threats from short-term social exclusion.

Figure 2: Cyberball (player is indicated by a hand at the bottom; ball tosses are programmed to either include or ostracize the player in a short game in which participants are told the primary purpose is to exercise their mental visualization skills).

2.5. Resignation: long-term effect of social exclusion

Based on the life-long investigation, Williams' hypothesis that individuals experience long-term ostracism by the same individual or group, or by any number of different sources, become numbed toward social exclusion or be cognitively deconstructed [41], and behaviour lacks self-regulation. The temporal need-threat model describes this stage as resignation, a long-term effect of ostracism. Williams suggests that during the first two stages of the model, an individual’s emotion toward social exclusion encourages them to do something to fortify their threatened need. The need for fortification could be regarded as a form of self-regulation. However, during the resignation stage, the individual becomes affective numb toward the long-term ostracism. It is a signal of passivity, impaired self-regulation, and a form of unwillingness to try, to work, a kind of psychological paralysis. All those resources to fortify the threatened need disappear, belongingness fortification becomes detachment and alienation, no longer maintain self-esteem and turn to depression, trying to prove worthy of attention become passive and feeling of worthlessness [17].

2.6. Continued social exclusion and SAD individuals

It seems that long-term ostracism debilitates psychological resilience by destroying an individual’s ability to regulate their emotion toward social exclusion. Negative emotion toward social situations is also a significant factor for SAD.

Emotion regulation (ER) is modifying and evaluating one’s emotional expression and response [42]. Expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal are two major research parts of ER. Gross and Jazaieri [43] suggest that expression suppression includes inhibition toward emotional expression (e.g., “putting on a poker face”) or control of one’s emotional expression by showing a different emotion rather than their current feeling (e.g., “putting a smile on” when sad. Becoming affective numb, no longer having emotional expression toward exclusion, is the strategy individuals utilise toward long-term social exclusion.

Recently, Dryman and Heimberg [44] reported that SAD and social anxiety consistently correlates with expression suppression, whether positive or negative emotion, under diverse situations. Furthermore, individuals with SAD have a higher desire to control and manage their emotions compared with individuals without SAD [45]. Compared with individuals without SAD, individuals with SAD show more inflexibility or rigidity when utilising ER strategies, for example, rumination, thought suppression, and expressive suppression, to control their emotions toward social situations [46].

Anger is usually considered a social emotion, as it arises from others' actions or words, expressed directly to a threatened situation, for example, in response to that perceived deliberate negligence from others or unfair harm [47]. Similar to individuals who suffer long-term social exclusion and show no emotion or action toward the helpless social situation, SAD individuals feel anger. They might have higher anger levels but poorer anger expression [48]. A recent study found that SAD individuals have more trait anger but prefer to suppress their anger compared to individuals without SAD; it is elevated anger-in response [49].

Understanding and expressing emotion toward social situations or social exclusion is essential for individuals to face things that happen during daily life. However, the long-term social exclusion experience or SAD challenges individuals to face and deal with their emotions and how to react to the situation.

3. Recovery from social exclusion

Social exclusion is a painful occasion for any individual who experiences it. Williams [17] found that little or nothing can be done to eliminate the initial pain caused by social exclusion. However, feeling pain rather than numbness might benefit individuals, as pain could motivate an individual to realize the potential risk to their status. Besides, it is usually quick for an individual to modify their behaviour to fortify their threatened needs and recover from occasional ostracism episodes.

However, individuals who fail to recover from short-term ostracism and keep this pain to the following social situation or who have to face long-term social exclusion might transition from short-term to long-term ostracism. Perpetual ostracism could sap an individual’s will to take practical steps to fortify their threatened needs and become despondent, alienated, and experience feelings of worthlessness. Worse, individuals become unable to make the effort to seek connections with others.

There is a similarity in clinical features between individuals suffering from long-term social exclusion and SAD. Bielak and Moscovitch [50] report that when entering a social situation, individuals with high social anxiety usually expect that their partners or audience observers will criticize or reject them. Furthermore, in social interaction situations, individuals with a diagnosed SAD and nonclinical individuals with high levels of SA are more likely to doubt their social ability and self-worth than non-SA individuals and view themselves as socially inept or undesirable [51]. To minimize the adverse effects of social interaction, individuals with SAD start to avoid social situations or tolerate them with considerable distress [52].

To reduce the psychological hurt of ostracism, DeWall et al. [53] suggest the use of pharmacological treatment, like acetaminophen, to release at least a few days of pain. It is also typical for SAD treatment to utilize drugs, typically antidepressants, the Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) [54]. For non-pharmacological treatment, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) could teach individuals the cognitive and behavioural competencies needed to take adaptive behaviour in the interpersonal and intrapersonal realities [55].

For individuals who avoid social situations because of their emotion regulation problem, Caletti et al. [54] suggest Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), a new innovative form of CBT, as an approach to treating those emotional-based social anxiety problems.

ACT approaches mainly focus on the “acceptance” and “defusion” from self-thoughts, like individual unpopular thoughts within social situations, and awareness of one’s value, to free individuals from thoughts or stories described by their mind [56] rather than repairing and modifying the disturbing symptom [54].

Hayes et al. [57] report that ACT supports individuals in learning the necessary techniques to accept rather than struggle or avoid their emotions, the “cognitive defusion”, a skill used to take a distance and not be controlled by it [58]. Based on emotional acceptance, ACT could reduce negative thoughts and provide an effective act rather than anxious-avoidant and worries about social situations [54].

4. Conclusion

Stable social connection is a necessary part of human mental and physical health. When social exclusion happens, individuals feel pain by it, and it threatens their fundamental needs. However, social exclusion is common during social situations, and because it could threaten the survival of individuals, humans are sensitive to ostracism. By fortifying the threatened needs, individuals could recover from the pain of ostracism quickly. Pro-social behaviour is the most apparent action for individuals to take after experiencing social exclusion. Through pro-social behaviour, individuals can reconnect with others quickly and be accepted by others.

Because of the individual difference, during the reflective stage, individuals with high social anxiety might recover slower from social exclusion than individuals with normal levels of social anxiety and tend to accumulate this pain till following social situation. The character of individuals with high social anxiety motivates them to avoid rather than reconnect with others. Individuals with higher social anxiety levels are more vulnerable to social exclusion, as they are more sensitive toward the threat of social exclusion and have a higher tendency to avoid the possibility of trying to recover from the pain caused by ostracism. When long-term social exclusion happens, individuals with higher social anxiety levels might be more helpless than others. Similar to SAD individuals, their first reaction toward social situations is to avoid it, and when exclusion happens, it is a challenge to face the emotion caused by ostracism. For these vulnerable individuals, the negative loop between themselves (unpopular, shyness) and the negative social situations (social exclusion or ostracism) could relate to a negative cycle for them. CBT has been proven to be helpful during the treatment of SAD. Recent research found that ACT might be more suitable for individuals with SAD and higher levels of social anxiety to help them face their emotions in the right way rather than avoid or control them.

Social exclusion is a painful experience; however, it is nearly unavoidable for social creatures. Through Williams’s temporal need-threat model of ostracism, it can be found that the reaction when individuals suffer social exclusion and how social anxiety affects an individual’s behaviour within a social situation. Research findings suggest that social exclusion could threaten individuals with higher social anxiety and SAD more than others, and how could such individuals face those threats through the assistance of the right treatments. Although social exclusion could be a significant factor related to SAD, the cause of SAD still needs to be confirmed, and more helpful treatment still needs to be explored.

References

[1]. Twenge, J. M., Baumeister, R. F., Tice, D. M., & Stucke, T. S. (2001). If you can’t join them, beat them: Effects of social exclusion on aggressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(6), 1058–1069. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.6.1058

[2]. Williams, K. D. (2007). Ostracism. Annual Review of Psychology, 58(1), 425–452. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085641

[3]. Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

[4]. Williams, K. D., & Nida, S. A. (2022). Ostracism and social exclusion: Implications for separation, social isolation, and loss. Current Opinion in Psychology, 47, 101353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101353

[5]. Maner, J. K., DeWall, C. N., Baumeister, R. F., & Schaller, M. (2007). Does social exclusion motivate interpersonal reconnection? Resolving the “porcupine problem”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(1), 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514. 92.1.42.

[6]. Eisenberger, N. I. (2012). The neural bases of social pain: Evidence for shared representations with physical pain. Psychosomatic Medicine, 74(2), 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013 e3182464dd1

[7]. Meltzer, H., Bebbington, P., Dennis, M. S., Jenkins, R., McManus, S., & Brugha, T. S. (2012). Feelings of loneliness among adults with mental disorder. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0515-8

[8]. Veale, D. (2003). Treatment of social phobia. Advances in psychiatric treatment, 9(4), 258-264. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.9.4.258

[9]. Coles, M. E., Ravid, A., Gibb, B., George-Denn, D., Bronstein, L. R., & McLeod, S. (2016). Adolescent mental health literacy: young people's knowledge of depression and social anxiety disorder. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58(1), 57-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.09.017

[10]. Furmark, T. (2002). Social phobia: overview of community surveys. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 105(2), 84-93. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.1r103.x

[11]. Wells, A. (2000). Modifying social anxiety: A cognitive approach. Shyness: Development, consolidation, and change. London: Routledge

[12]. Tice, D. M. (1992). Self-concept change and self-presentation: The looking glass self is also a magnifying glass. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(3), 435-451. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.3.435

[13]. Schuster, T. L., Kessler,R.C., & Aseltine,R.H.(1990). Supportive interactions,negative interactions, and depressed mood. American Journal of Community Psychology, 18(3), 423–438.

[14]. Cacioppo, J. T., & Hawkley, L. C. (2009). Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(10), 447–454.

[15]. Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., & Thisted, R.A. (2010). Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychology and Aging, 25(2), 453–463.

[16]. Stein, M. B., & Stein, D. J. (2008). Social anxiety disorder. Lancet, 371(9618), 1115–1125.

[17]. Williams, K. D. (2009). Ostracism: A temporal need‐threat model. Advances in experimental social psychology, 41, 275-314.

[18]. Zadro, L., Williams, K. D., & Richardson, R. (2004). How low can you go? Ostracism by a computer lowers belonging, control, self-esteem, and meaningful existence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 560–567.

[19]. Eisenberger, N. I., Lieberman, M. D., & Williams, K. D. (2003). Does rejection hurt? An f MRI study of social exclusion. Science, 302, 290–292.

[20]. Bagg, D., & Williams, K. D. (2008). The sympathetic effects of witnessing ostracism, Chicago: Presented at the Midwestern Psychological Association

[21]. Coyne, S. M., Nelson, D. A., Robinson, S. L., & Gundersen, N. C. (2011). Is viewing ostracism on television distressing? The Journal of Social Psychology, 151(3), 213–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224540903365570

[22]. Haselton, M. G., & Buss, D. M. (2000). Error management theory: A new perspective on biases cross-sex mind reading. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 81–91.

[23]. Leary, M. R., Tambor, E. S., Terdal, S. K., & Downs, D. L. (1995). Self-esteem as an interpersonal monitor: The sociometer hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 518–530.

[24]. Hogg, M. A., & Vaughan, G. M. (2010). Essentials of social psychology. Pearson.

[25]. Stillman, T. F., Baumeister, R. F., Lambert, N. M., Crescioni, A. W., DeWall, C. N., & Fincham, F. D. (2009). Alone and without purpose: Life loses meaning following social exclusion. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(4), 686–694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.03.007

[26]. Greenberg, J., Solomon, S., Pyszczynski, T., Rosenblatt, A., Burling, J., Lyon, D., Simon, L., & Pinel, E. (1992). Why do people need self-esteem? Converging evidence that self-esteem serves an anxiety-buffering function. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 913–922.

[27]. Zadro, L., Boland, C., & Richardson, R. (2006). How long does it last? the persistence of the effects of ostracism in the socially anxious. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42(5), 692–697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2005.10.007

[28]. Oaten, M. R., Williams, K. D., Jones, A., & Zadro, L. (2008). The effects of ostracism on selfregulation in the socially anxious. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 27, 471–404.

[29]. Ayduk, O., Gyurak, A., & Luerssen, A. (2007). Individual differences in the rejection aggression link in the hot sauce paradigm: The case of rejection sensitivity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44, 775–782.

[30]. Fung, K., & Alden, L. E. (2017). Once hurt, twice shy: Social pain contributes to social anxiety. Emotion, 17(2), 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000223

[31]. Hudd, T., & Moscovitch, D. A. (2021). Reconnecting in the face of exclusion: Individuals with high social anxiety may feel the push of social pain, but not the pull of social rewards. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 46(2), 420–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-021-10263-z

[32]. Maner, J. K., DeWall, C. N., Baumeister, R. F., & Schaller, M. (2007). Does social exclusion motivate interpersonal reconnection? Resolving the “porcupine problem.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(1), 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022- 3514.92.1.42

[33]. DeWall, C. N., & Richman, S. B. (2011). Social Exclusion and the desire to reconnect. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(11), 919–932. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00383.x

[34]. Mallott, M. A., Maner, J. K., DeWall, N., & Schmidt, N. B. (2009). Compensatory deficits following rejection: The role of social anxiety in disrupting affiliative behavior. Depression and Anxiety, 26(5), 438–446. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20555

[35]. Mead, N. L., Baumeister, R. F., Stillman, T. F., Rawn, C. D., & Vohs, K. D. (2011). Social exclusion causes people to spend and consume strategically in the service of affiliation. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(5), 902–919. https://doi.org/10.1086/ 656667

[36]. Hudd, T., & Moscovitch, D. A. (2020). Coping with social wounds: How social pain and social anxiety influence access to social rewards. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 68, 101572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jbtep.2020.101572

[37]. Steinman, S. A., Gorlin, E. I., & Teachman, B. A. (2014). Cognitive biases among individuals with social anxiety. The Wiley Blackwell handbook of social anxiety disorder, 321-343. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118653920.ch15

[38]. Hudd, T., & Moscovitch, D. A. (2021). Reconnecting in the face of exclusion: Individuals with high social anxiety may feel the push of social pain, but not the pull of social rewards. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 46(2), 420–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-021-10263-z

[39]. DeWall, C. N., Buckner, J. D., Lambert, N. M., Cohen, A. S., & Fincham, F. D. (2010). Bracing for the worst, but behaving the best: Social anxiety, hostility, and behavioral aggression. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 24(2), 260–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. janxdis.2009.12.002

[40]. Hudd, T., & Moscovitch, D. A. (2023). Social anxiety inhibits needs repair following exclusion in both relational and non-relational reward contexts: The mediating role of positive affect. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 162, 104270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2023.104270

[41]. Baumeister, R. F., DeWall, C. N., Ciarocco, N. L., & Twenge, J. M. (2006). Social exclusion impairs self-regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 589–604.

[42]. Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271–299. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089- 2680.2.3.271

[43]. Gross, J. J., & Jazaieri, H. (2014). Emotion, emotion regulation, and psychopathology: An affective science perspective. Clinical Psychological Science, 2, 387–401. https:// doi.org/10.1177/2167702614536164

[44]. Dryman, M. T., & Heimberg, R. G. (2018). Emotion regulation in social anxiety and depression: A systematic review of expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal. Clinical Psychology Review, 65, 17–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2018.07.004

[45]. Goodman, F. R., Daniel, K. E., Eldesouky, L., Brown, B. A., & Kneeland, E. T. (2021). How do people with social anxiety disorder manage daily stressors? Deconstructing emotion regulation flexibility in daily life. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 6, 100210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100210

[46]. Goodman, F. R., Kashdan, T. B., Stiksma, M. C., & Blalock, D. V. (2019). Personal strivings to understand anxiety disorders: Social anxiety as an exemplar. Clinical Psychological Science, 7(2), 283–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702618804778

[47]. Kring, A. M. (2000). Gender and anger. In A. H. Fischer (Ed.), Studies in emotion and social interaction (2nd ed., pp. 211–231). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/ 10.1017/CBO9780511628191.011.

[48]. Erwin, B. A., Heimberg, R. G., Schneier, F. R., & Liebowitz, M. R. (2003). Anger experience and expression in social anxiety disorder: Pretreatment profile and predictors of attrition and response to cognitive-behavioral treatment. Behavior Therapy, 34(3), 331–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(03)80004-7

[49]. Conrad, R., Forstner, A. J., Chung, M.-L., Mücke, M., Geiser, F., Schumacher, J., & Carnehl, F. (2021). Significance of anger suppression and preoccupied attachment in social anxiety disorder: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1), 116. https:// doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03098-1

[50]. Bielak, T., & Moscovitch, D. A. (2012). Friend or foe? Memory and expectancy biases for faces in social anxiety. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology, 3, 42e61. http://dx.doi.org/10.5127/jep.019711.

[51]. Moscovitch, D. A., Rowa, K., Paulitzki, J. R., Ierullo, M. D., Chiang, B., Antony, M. M., & McCabe, R. E. (2013). Self-portrayal concerns and their relation to safety behaviors and negative affect in social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51(8), 476–486.

[52]. Goodman, F. R., Rum, R., Silva, G., & Kashdan, T. B. (2021). Are people with social anxiety disorder happier alone? Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 84, 102474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102474

[53]. DeWall, C. N., MacDonald, G., Webster, G. D., Tice, D. M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2008). Acetaminophen reduces psychological hurt feelings over time. Manuscript under review.

[54]. Caletti, E., Massimo, C., Magliocca, S., Moltrasio, C., Brambilla, P., & Delvecchio, G. (2022). The role of the acceptance and commitment therapy in the treatment of social anxiety: An updated scoping review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 310, 174–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.05.008

[55]. Mayo-Wilson, E., Dias, S., Mavranezouli, I., Kew, K., Clark, D.M., Ades, A.E., Pilling, S., 2014. Psychological and pharmacological interventions for social anxiety disorder in adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 1 (5), 368–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70329-3

[56]. Hayes, S. C., Pistorello, J., & Levin, M. E. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy as a unified model of behavior change. The Counseling Psychologist, 40(7), 976-1002. https://doi. org/10.1177/0011000012460836.

[57]. Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour research and therapy, 44(1), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006

[58]. Luoma, J. B., Hayes, S. C., & Walser, R. D. (2007). Learning ACT: An acceptance & commitment therapy skills-training manual for therapists. New Harbinger Publications.

Cite this article

Chen,Z. (2024). Social Exclusion and Social Anxiety Disorder: The Temporal Need-threat Model of Ostracism. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,38,148-156.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Twenge, J. M., Baumeister, R. F., Tice, D. M., & Stucke, T. S. (2001). If you can’t join them, beat them: Effects of social exclusion on aggressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(6), 1058–1069. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.6.1058

[2]. Williams, K. D. (2007). Ostracism. Annual Review of Psychology, 58(1), 425–452. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085641

[3]. Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

[4]. Williams, K. D., & Nida, S. A. (2022). Ostracism and social exclusion: Implications for separation, social isolation, and loss. Current Opinion in Psychology, 47, 101353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101353

[5]. Maner, J. K., DeWall, C. N., Baumeister, R. F., & Schaller, M. (2007). Does social exclusion motivate interpersonal reconnection? Resolving the “porcupine problem”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(1), 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514. 92.1.42.

[6]. Eisenberger, N. I. (2012). The neural bases of social pain: Evidence for shared representations with physical pain. Psychosomatic Medicine, 74(2), 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013 e3182464dd1

[7]. Meltzer, H., Bebbington, P., Dennis, M. S., Jenkins, R., McManus, S., & Brugha, T. S. (2012). Feelings of loneliness among adults with mental disorder. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0515-8

[8]. Veale, D. (2003). Treatment of social phobia. Advances in psychiatric treatment, 9(4), 258-264. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.9.4.258

[9]. Coles, M. E., Ravid, A., Gibb, B., George-Denn, D., Bronstein, L. R., & McLeod, S. (2016). Adolescent mental health literacy: young people's knowledge of depression and social anxiety disorder. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58(1), 57-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.09.017

[10]. Furmark, T. (2002). Social phobia: overview of community surveys. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 105(2), 84-93. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.1r103.x

[11]. Wells, A. (2000). Modifying social anxiety: A cognitive approach. Shyness: Development, consolidation, and change. London: Routledge

[12]. Tice, D. M. (1992). Self-concept change and self-presentation: The looking glass self is also a magnifying glass. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(3), 435-451. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.3.435

[13]. Schuster, T. L., Kessler,R.C., & Aseltine,R.H.(1990). Supportive interactions,negative interactions, and depressed mood. American Journal of Community Psychology, 18(3), 423–438.

[14]. Cacioppo, J. T., & Hawkley, L. C. (2009). Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(10), 447–454.

[15]. Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., & Thisted, R.A. (2010). Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychology and Aging, 25(2), 453–463.

[16]. Stein, M. B., & Stein, D. J. (2008). Social anxiety disorder. Lancet, 371(9618), 1115–1125.

[17]. Williams, K. D. (2009). Ostracism: A temporal need‐threat model. Advances in experimental social psychology, 41, 275-314.

[18]. Zadro, L., Williams, K. D., & Richardson, R. (2004). How low can you go? Ostracism by a computer lowers belonging, control, self-esteem, and meaningful existence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 560–567.

[19]. Eisenberger, N. I., Lieberman, M. D., & Williams, K. D. (2003). Does rejection hurt? An f MRI study of social exclusion. Science, 302, 290–292.

[20]. Bagg, D., & Williams, K. D. (2008). The sympathetic effects of witnessing ostracism, Chicago: Presented at the Midwestern Psychological Association

[21]. Coyne, S. M., Nelson, D. A., Robinson, S. L., & Gundersen, N. C. (2011). Is viewing ostracism on television distressing? The Journal of Social Psychology, 151(3), 213–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224540903365570

[22]. Haselton, M. G., & Buss, D. M. (2000). Error management theory: A new perspective on biases cross-sex mind reading. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 81–91.

[23]. Leary, M. R., Tambor, E. S., Terdal, S. K., & Downs, D. L. (1995). Self-esteem as an interpersonal monitor: The sociometer hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 518–530.

[24]. Hogg, M. A., & Vaughan, G. M. (2010). Essentials of social psychology. Pearson.

[25]. Stillman, T. F., Baumeister, R. F., Lambert, N. M., Crescioni, A. W., DeWall, C. N., & Fincham, F. D. (2009). Alone and without purpose: Life loses meaning following social exclusion. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(4), 686–694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.03.007

[26]. Greenberg, J., Solomon, S., Pyszczynski, T., Rosenblatt, A., Burling, J., Lyon, D., Simon, L., & Pinel, E. (1992). Why do people need self-esteem? Converging evidence that self-esteem serves an anxiety-buffering function. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 913–922.

[27]. Zadro, L., Boland, C., & Richardson, R. (2006). How long does it last? the persistence of the effects of ostracism in the socially anxious. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42(5), 692–697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2005.10.007

[28]. Oaten, M. R., Williams, K. D., Jones, A., & Zadro, L. (2008). The effects of ostracism on selfregulation in the socially anxious. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 27, 471–404.

[29]. Ayduk, O., Gyurak, A., & Luerssen, A. (2007). Individual differences in the rejection aggression link in the hot sauce paradigm: The case of rejection sensitivity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44, 775–782.

[30]. Fung, K., & Alden, L. E. (2017). Once hurt, twice shy: Social pain contributes to social anxiety. Emotion, 17(2), 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000223

[31]. Hudd, T., & Moscovitch, D. A. (2021). Reconnecting in the face of exclusion: Individuals with high social anxiety may feel the push of social pain, but not the pull of social rewards. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 46(2), 420–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-021-10263-z

[32]. Maner, J. K., DeWall, C. N., Baumeister, R. F., & Schaller, M. (2007). Does social exclusion motivate interpersonal reconnection? Resolving the “porcupine problem.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(1), 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022- 3514.92.1.42

[33]. DeWall, C. N., & Richman, S. B. (2011). Social Exclusion and the desire to reconnect. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(11), 919–932. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00383.x

[34]. Mallott, M. A., Maner, J. K., DeWall, N., & Schmidt, N. B. (2009). Compensatory deficits following rejection: The role of social anxiety in disrupting affiliative behavior. Depression and Anxiety, 26(5), 438–446. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20555

[35]. Mead, N. L., Baumeister, R. F., Stillman, T. F., Rawn, C. D., & Vohs, K. D. (2011). Social exclusion causes people to spend and consume strategically in the service of affiliation. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(5), 902–919. https://doi.org/10.1086/ 656667

[36]. Hudd, T., & Moscovitch, D. A. (2020). Coping with social wounds: How social pain and social anxiety influence access to social rewards. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 68, 101572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jbtep.2020.101572

[37]. Steinman, S. A., Gorlin, E. I., & Teachman, B. A. (2014). Cognitive biases among individuals with social anxiety. The Wiley Blackwell handbook of social anxiety disorder, 321-343. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118653920.ch15

[38]. Hudd, T., & Moscovitch, D. A. (2021). Reconnecting in the face of exclusion: Individuals with high social anxiety may feel the push of social pain, but not the pull of social rewards. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 46(2), 420–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-021-10263-z

[39]. DeWall, C. N., Buckner, J. D., Lambert, N. M., Cohen, A. S., & Fincham, F. D. (2010). Bracing for the worst, but behaving the best: Social anxiety, hostility, and behavioral aggression. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 24(2), 260–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. janxdis.2009.12.002

[40]. Hudd, T., & Moscovitch, D. A. (2023). Social anxiety inhibits needs repair following exclusion in both relational and non-relational reward contexts: The mediating role of positive affect. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 162, 104270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2023.104270

[41]. Baumeister, R. F., DeWall, C. N., Ciarocco, N. L., & Twenge, J. M. (2006). Social exclusion impairs self-regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 589–604.

[42]. Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271–299. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089- 2680.2.3.271

[43]. Gross, J. J., & Jazaieri, H. (2014). Emotion, emotion regulation, and psychopathology: An affective science perspective. Clinical Psychological Science, 2, 387–401. https:// doi.org/10.1177/2167702614536164

[44]. Dryman, M. T., & Heimberg, R. G. (2018). Emotion regulation in social anxiety and depression: A systematic review of expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal. Clinical Psychology Review, 65, 17–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2018.07.004

[45]. Goodman, F. R., Daniel, K. E., Eldesouky, L., Brown, B. A., & Kneeland, E. T. (2021). How do people with social anxiety disorder manage daily stressors? Deconstructing emotion regulation flexibility in daily life. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 6, 100210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100210

[46]. Goodman, F. R., Kashdan, T. B., Stiksma, M. C., & Blalock, D. V. (2019). Personal strivings to understand anxiety disorders: Social anxiety as an exemplar. Clinical Psychological Science, 7(2), 283–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702618804778

[47]. Kring, A. M. (2000). Gender and anger. In A. H. Fischer (Ed.), Studies in emotion and social interaction (2nd ed., pp. 211–231). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/ 10.1017/CBO9780511628191.011.

[48]. Erwin, B. A., Heimberg, R. G., Schneier, F. R., & Liebowitz, M. R. (2003). Anger experience and expression in social anxiety disorder: Pretreatment profile and predictors of attrition and response to cognitive-behavioral treatment. Behavior Therapy, 34(3), 331–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(03)80004-7

[49]. Conrad, R., Forstner, A. J., Chung, M.-L., Mücke, M., Geiser, F., Schumacher, J., & Carnehl, F. (2021). Significance of anger suppression and preoccupied attachment in social anxiety disorder: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1), 116. https:// doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03098-1

[50]. Bielak, T., & Moscovitch, D. A. (2012). Friend or foe? Memory and expectancy biases for faces in social anxiety. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology, 3, 42e61. http://dx.doi.org/10.5127/jep.019711.

[51]. Moscovitch, D. A., Rowa, K., Paulitzki, J. R., Ierullo, M. D., Chiang, B., Antony, M. M., & McCabe, R. E. (2013). Self-portrayal concerns and their relation to safety behaviors and negative affect in social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51(8), 476–486.

[52]. Goodman, F. R., Rum, R., Silva, G., & Kashdan, T. B. (2021). Are people with social anxiety disorder happier alone? Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 84, 102474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102474

[53]. DeWall, C. N., MacDonald, G., Webster, G. D., Tice, D. M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2008). Acetaminophen reduces psychological hurt feelings over time. Manuscript under review.

[54]. Caletti, E., Massimo, C., Magliocca, S., Moltrasio, C., Brambilla, P., & Delvecchio, G. (2022). The role of the acceptance and commitment therapy in the treatment of social anxiety: An updated scoping review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 310, 174–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.05.008

[55]. Mayo-Wilson, E., Dias, S., Mavranezouli, I., Kew, K., Clark, D.M., Ades, A.E., Pilling, S., 2014. Psychological and pharmacological interventions for social anxiety disorder in adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 1 (5), 368–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70329-3

[56]. Hayes, S. C., Pistorello, J., & Levin, M. E. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy as a unified model of behavior change. The Counseling Psychologist, 40(7), 976-1002. https://doi. org/10.1177/0011000012460836.

[57]. Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour research and therapy, 44(1), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006

[58]. Luoma, J. B., Hayes, S. C., & Walser, R. D. (2007). Learning ACT: An acceptance & commitment therapy skills-training manual for therapists. New Harbinger Publications.