1. Introduction

Regarding the birth of Hu Jia, poet Du Zhi pointed out in his poem that Hu Jia is a blowing instrument of the Rong tribe. The activities of the Rong tribe were in the non-Huaxia tribes in Shaanxi and Gansu, and they gradually migrated eastward over time. Among them, the Qiongrong (a branch of the Western Rong ethnic group) migrated north during the Yin Shang period [1]. Dictionary of Ancient Chinese Place Names records: “Jialu River, the source is in Ordos, passing through Jia County in Yulin, Shaanxi, and then flowing into the Yellow River.” Because it is rich in reeds, it provides ample conditions for the birth of the “Jia” blowing instrument. This place is also where the ancestors of the Xiongnu tribe lived.

As an external instrument of the Hu people, Hu Jia has undergone changes in various dynasties. Most scholars believe that it has been lost. This paper will prove the view that Hu Jia has not been lost through the changes in the manufacturing and hole system of Hu Jia in different dynasties. This paper mainly conducts research through literature analysis method. The research in this paper is of great significance for the improvement of Hu Jia as a musical instrument, the development, inheritance, and promotion of Hu Jia in ethnic orchestras, and provides new research ideas for future researchers studying Hu Jia.

2. Introduction to Hu Jia

2.1. Shape and Structure

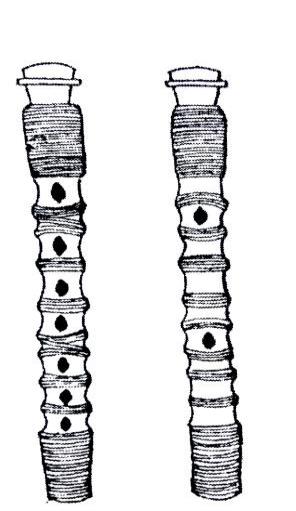

Hu Jia is an ancient wind instrument that was popular in the northern frontier and the Western Regions during the Han Dynasty. It has a mournful sound [2]. Hu Jia was originally made from reeds and came from the Xiongnu. However, there is no detailed record of when the Xiongnu started using this instrument, but there are many ancient poems that prove it was one of the instruments used by the Xiongnu. There are two types of Hu Jia in terms of structure. One is made of reeds without side holes. Chen Chang, a Song Dynasty scholar, wrote in Book of Music: Hu Du: Subgroup of Bamboo, "Hu Jia is similar to Yu Li but without holes, and it was used in large-scale celebrations held by the country." The other type is made of wood and has three side finger holes. Qing Hui Dian Tu: Yue Qi Ba (Illustrations of Court Music: Eight Musical Instruments) states, "Hu Jia is made of wood, has three holes, and the body is decorated with the outer skin of a wooden stick [3]." Both were written during the late Han Dynasty. Tai Ping Yu Lan records, "Hu Jia is made of rolled reed leaves by the Hu people and is used for music [4]." Hu Jia is divided into Da Hu Jia (Large Hu Jia) and Xiao Hu Jia (Small Hu Jia) (as shown in Figure 1), where the left one is Xiao Hu Jia and the right one is Da Hu Jia. It can be seen that it is a unique non-hole wind instrument, just as The Book of Music mentions that Da Hu Jia and Xiao Hu Jia resemble Bi Li and have no holes.

Figure 1: Large Hu Jia and Small Hu Jia (Hu Jia variants)[3]

2.2. Performance Technique

Regarding the playing technique of Hu Jia, the poet Fan Qin of the Jian'an period mentioned a special blowing method that produces a unique tone by using the throat in his Letter to the Crown Prince. This special playing technique is still preserved in remote mountainous pastoral areas such as the Kazakhs in Xinjiang and the Mongols in the Altai region. The Kazakhs call it "Sebezge" and the Mongols call it "Chaoer" or "Maodeng Chaoer" [1].

Hu Jia utilizes the principles of overblowing to create a just intonation system similar to that of the ancient qin. The qin determines its pitch based on harmonics, while Hu Jia can produce harmonics at the octave and twelfth, sharing the same underlying principles. Due to its unique overblowing technique, Hu Jia produces a soft and mellow tone that is distant and melodious. Many ancient poets have recorded Hu Jia's mastery of the "sorrowful sound" in their poems. Hu Jia's distinctive timbre, coupled with its matured playing technique, led to its rapid development and its ability to deeply resonate with the listener's emotions and thoughts.

The ancient poem Ode to the Jia records that Hu Jia cannot only play the pentatonic scale of ancient music, but also perform microtones such as the qingjiao (slightly lowered pitch) and qingyu (slightly raised pitch), as well as the biangong (raised pitch) and bianzhi (lowered pitch) which are commonly used. This indicates that during the period of Wei, Jin and Southern and Northern Dynasties, the playing technique of Hu Jia had already matured significantly.

3. Development of Hu Jia

During the Han Dynasty, Hu Jia was brought into the Central Plains through the Silk Road, spanning thousands of miles. Due to its unique sound as a foreign instrument, it was highly favored by scholars and poets. As a result, there are numerous poems and ancient texts about Hu Jia. However, with the migration of the Xiongnu tribe and the introduction of Western music, its original form became greatly weakened and has long been unfamiliar to people. It was not until the Qing Dynasty that the court promoted "exotic music" and formed the Mongolian Kalhun Prince's Orchestra, also known as the "Mongolian Hu Jia Section" of the imperial court [1].

Japanese folklorist Mr. Torii captured a photo around 1920 in the Horqin Grassland (Figure 2), which is consistent with the depiction of Hu Jia in the Qing Dynasty's collection Four Scenes of a Banquet in the Frontier preserved in the Palace Museum (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Performance scene on the Khorchin Grassland

Figure 3: Partial image from Four Scenes of a Frontier Banquet

According to the records of "Imperial Ritual Objects of the Qing Dynasty", the length of the blowing section of Hu Jia is two chi and four cun, with three finger holes. It can be seen that the Hu Jia of the Qing Dynasty was an improved version of the wooden three-hole Hu Jia from the late Han Dynasty by Qing court musicians. Hu Jia has continued to develop to this day, with improvements in its material varying with the changing times. The Qing Dynasty Hu Jia restored by the Chifeng Cultural Troupe in Inner Mongolia is equipped with steel reeds inside the tube wall, transforming it into a free-reed aerophone. This allows for greater volume and produces a solid and resonant tone, thereby meeting the needs of court music.

4. The Evolution of Hu Jia

In his book A Study on East Asian Musical Instruments, renowned Japanese scholar Mr. Hayashi Kenzo mentioned that he believed Hu Jia had already been lost during the Han Dynasty [5]. Other scholars also pointed out that Sebezge is Hu Jia of the Han Dynasty. The author also analyzed the above two questions.

In the Book of Music, it is recorded that the shape of Hu Jia is similar to the yu li but without holes, and its predecessor is called "Gu," which also has no holes. However, there are written records in the Three Kingdoms period that Hu Jia can play five notes, indicating that Hu Jia with holes appeared during this period. In the Qing Hui Dian Tu: Eight Musical Instruments restored during the Qing Dynasty, it is also stated that Hu Jia is a wooden wind instrument with three holes. From this, it can be inferred that Hu Jia had changed from a no-holes instrument to a holes instrument from the Western Han Dynasty to the Eastern Han Dynasty, and during the Three Kingdoms period, it developed into a multi-holed instrument with no specific records. It was only during the Qing Dynasty that Hu Jia was clearly documented to have three holes.

Therefore, the author believes that after the introduction of Hu Jia by the Hu people, its structure may have changed slightly. It is possible that both the no-holes Hu Jia and the three-holes Hu Jia existed during the Han Dynasty, just like the present-day ruan. Different varieties with or without sound holes on the front panel have slight differences in appearance, which is very normal. However, the Hu Jia with holes may not have been commonly seen during the Western Han Dynasty, so there were no records. It was not until the Three Kingdoms period that it was widely used. The no-holes Hu Jia of the Han Dynasty was probably similar to today's whistle, and in order to play multiple melodies, it was modified by later generations and increased to three or four holes. The nine-hole Bi Li has also been developed through instrument improvements, and it has been proven that the predecessor of Bi Li is indeed the Hu Jia of the Han Dynasty.

In the ancient book Kitabu Diwani Lughat-it-Turki, it is mentioned that "Sebezge" is a type of Xiao (a vertical bamboo flute). This indicates that as early as before the 11th century (Southern Song Dynasty), Sebezge had already appeared and circulated among the people, passing down through generations until today. Its body is made of a sturdy type of reed, and nowadays, it is commonly made with poplar, pine, or felt-covered bamboo. The length of the body is approximately 50 centimeters, with a diameter of 1.5 centimeters. The body is hollow, without a reed mechanism. There are three or four finger holes on the body, consistent with the description of the Hu Jia in Qing Dynasty texts (Figure 4), and its shape is extremely similar to Bi Li (with nine holes) (Figure 5).

Figure 4: Sebezge Figure 5: Bi Li

In the earlier text, the author mentioned that most Hu Jia were made from reed leaves. However, according to the description in the Book of Music, the Hu Jia with a mournful tone is made of sheep bones, but without holes [6]. This shows that the materials used for making Hu Jia also include sheep bones, sheep horns, and other such materials, which are quite different from Sebezge. Therefore, the Sebezge that has been passed down until today is not Hu Jia. It is simply a tubular instrument with three or four holes that appeared after the Han Dynasty and has a similar shape to Hu Jia.

In his book A Study on East Asian Musical Instruments, Mr. Hayashi Kenzo suggested that Hu Jia has become extinct. However, the author disagrees with this viewpoint. Here are my reasons:

During the Western Jin Dynasty, Liu Kun, the governor of Bingzhou, used to play Hu Jia when he blew the horn under the moon to drive away the enemy. According to research, Hu Jia he played was a three-hole Hu Jia, with the same structure and number of holes as Hu Jia recorded in the Qing Dynasty. It could produce a five-tone scale with a range of twelve degrees and could be played using throat techniques. It often combined throat sounds with pipe sounds to produce sound, or used throat sounds to lead the pipe sounds. In 1985, scholars discovered this kind of Hu Jia still being used in the Handasatu Mongolian Autonomous Township in Altay, Xinjiang, and named it the "Altay Hu Jia Flute." The instrument is made of wood, with a length of 58.5cm and a diameter of 1.8cm, and has three circular tone holes at the lower part, with no reeds at the upper end of the pipe [7].

The appearance of the three-hole Hu Jia in the Western Jin Dynasty and the Altay Hu Jia are the same as the three-hole Hu Jia recorded in the Qing Dynasty, which proves that Hu Jia never disappeared.

In various ancient texts, Hu Jia was depicted with different numbers of holes and different lengths. As mentioned earlier, the Ode to the Jia recorded that Hu Jia could play five notes and produce overtones, which suggests that Hu Jia during the Period of Wei, Jin and Southern and Northern Dynasties after the Han Dynasty must have been a flute with holes and capable of playing melodies. Therefore, it can be concluded that a flute with holes capable of playing five notes is a long flute, while a flute without holes is a short flute.

In recent years, Hu Jia has been revived and used by the Cultural Troupe of Chifeng City in Inner Mongolia. This troupe has achieved remarkable results in the development of Mongolian national musical instruments. They have developed instruments such as Hu Jia, Bi Li, Komuz, Yatok, and Hulei, which have changed the monotonous and backward state of Mongolian musical instruments. Many of these instruments were already lost or on the verge of being lost. The Chifeng City Intangible Cultural Heritage Protection Center has also established Hu Jia and Bi Li performance training classes. In 2011, these classes started at the Chifeng Mongolian Middle School, which undoubtedly played a crucial role in the inheritance of minority musical instruments in our country. The following image is a record of a solo performance of Hu Jia by the Cultural Troupe (Figure 6). Hu Jia revived by the Chifeng City Cultural Troupe is from the Qing Dynasty. It also has three holes and is equipped with steel reeds. The instrument is composed of the blowing mouth, the pipe body, and the trumpet-shaped mouthpiece made from curved cow horn. Although the overall development was successful, the process was undoubtedly arduous. The excavation and trial production of these ancient instruments, as well as the formation of Mongolian folk ensembles, can be described as challenging and not easy to achieve.

Figure 6: Hu Jia solo by the Chifeng Art Troupe

5. Conclusion

This paper explores the development and changes of Hu Jia, a minority musical instrument. Referring to a large number of literature, it analyzes the different forms of Hu Jia in various dynasties. Through research, it is found that Hu Jia has not been lost. As mentioned earlier, although Hu Jia has been improved through research and development, it has not completely "disappeared". However, there are still very few people who know or understand it today. As one of the wind instruments, the sound of Hu Jia is similar to the Xiao, soft and not harsh. Its unique tone can complement the tones of other ethnic musical instruments. Every ethnic musical instrument has its own significance and is unique. The author hopes that Hu Jia can be promoted in various music academies and a separate major can be established. In this way, it is believed that Hu Jia can once again enter people's field of vision in the future. This paper does not compare and analyze the three similar ancient ancestral aerophones, Hu Jia, Bi Li, and Qiang Flute, in terms of tone, material, number of holes, and appearance period. As for the Bi Li, the period of its appearance has been controversial until now. Therefore, these three kinds of similar ancient instruments still have great research significance and research value.

References

[1]. Zhao, F. Complete Works of Zhao Feng: Chinese Musical Instruments[M]. Central Conservatory of Music Press, Supplement, 2016:177.

[2]. Lu, W. Z.. Annotations on 200 Ancient Chinese Music Poems[M]. 1993: 334.

[3]. Ying, Y. Q. & Sun, K.R. Great Dictionary of Chinese Musical Instruments[M]. Shanghai Century Publishing Group Education Press, 2015: 161.

[4]. Li, F., Li, M., & Xu, X. Taiping Yulan (Vol. 581)[M]. Zhonghua Book Company, 2000.

[5]. Hayashi, Kenzo. Study of East Asian Instruments[M]. Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House, 2013: 389.

[6]. Tang, C. Y. The Development of Hu Jia[J]. Chinese Music Journal, 1986: (04).

[7]. Wang, X. P. Brief Compilation of Chinese Ethnic Musical Instruments[M]. 2013: 84.

Cite this article

Li,J. (2024). Research on the Origin and Evolution of Hu Jia. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,39,282-287.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Zhao, F. Complete Works of Zhao Feng: Chinese Musical Instruments[M]. Central Conservatory of Music Press, Supplement, 2016:177.

[2]. Lu, W. Z.. Annotations on 200 Ancient Chinese Music Poems[M]. 1993: 334.

[3]. Ying, Y. Q. & Sun, K.R. Great Dictionary of Chinese Musical Instruments[M]. Shanghai Century Publishing Group Education Press, 2015: 161.

[4]. Li, F., Li, M., & Xu, X. Taiping Yulan (Vol. 581)[M]. Zhonghua Book Company, 2000.

[5]. Hayashi, Kenzo. Study of East Asian Instruments[M]. Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House, 2013: 389.

[6]. Tang, C. Y. The Development of Hu Jia[J]. Chinese Music Journal, 1986: (04).

[7]. Wang, X. P. Brief Compilation of Chinese Ethnic Musical Instruments[M]. 2013: 84.