1. Introduction

In recent years, the evolving dynamics and increasing complexities within the economic relationship between the United States and China have significantly impacted the global economic landscape [1, 2]. The subsequent shifts in global supply chains have emerged as a central focus, placing Southeast Asia in the spotlight due to its strategic geographical location, economic dynamism, and robust manufacturing potential [3]. Notably, Vietnam and Malaysia have quickly risen as key destinations for production relocation, reflecting their growing significance in global economic and geopolitical contexts [4, 5].Vietnam has effectively leveraged its competitive labor costs, stable policy environment, and strong integration into global markets to attract substantial Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), especially in electronics and textile sectors [6]. Meanwhile, Malaysia has enhanced its strategic positioning in semiconductor and high-tech industries, progressively upgrading towards higher-value-added segments [7]. Nonetheless, such advancements bring their own set of challenges, including infrastructure constraints, labor shortages, and geopolitical uncertainties, highlighting the need for these nations to carefully balance economic opportunities with strategic autonomy [8].Although previous studies have examined initial responses to the shifting US–China economic relationship and its implications for Southeast Asia [9], there remains a limited systematic exploration of how specific countries within the region are adjusting to their evolving roles and managing associated challenges. Using a geoeconomic and global value chain perspective, this paper analyzes the strategic approaches adopted by Vietnam and Malaysia in navigating this changing landscape. This study aims to contribute deeper insights into the dynamics of regional supply chain adjustments and inform strategic policymaking.

2. Theoretical framework and research perspective

This study employs two key theoretical lenses to explore the reconfiguration of regional supply chains in Southeast Asia: Geo-economics and Global Value Chains (GVC).

Geo-economics emphasizes the strategic interplay between economic policies, geographic location, and geopolitical competition among nations [10]. In the context of evolving US–China relations, geo-economic analysis provides valuable insights into how Southeast Asian countries like Vietnam and Malaysia strategically navigate the complexities posed by great-power economic rivalry, effectively using economic policy as a strategic tool to enhance their international standing [11].Complementing this, the Global Value Chains framework sheds light on how the global economic landscape shapes production, investment, and trade flows across borders [12]. By using GVC theory, this paper examines the ways in which countries manage their positions within global production networks, strategically transitioning toward higher-value-added activities while adapting to shifting global dynamics [13]. The theory is particularly relevant to understanding structural opportunities and constraints faced by nations in their efforts to capture greater value from their participation in global markets.

Moreover, the study incorporates the concept of strategic balancing to analyze how Southeast Asian countries maintain autonomy by diversifying economic partnerships and avoiding excessive reliance on any single dominant power [14]. By integrating these theoretical perspectives, this research seeks to comprehensively understand the strategic choices made by Vietnam and Malaysia in adapting to the evolving economic landscape shaped by US–China relations.

3. Strategic shifts in Southeast Asia amid evolving Us–China relations

The evolving economic relationship between the United States and China has induced significant strategic shifts within Southeast Asia, as regional economies adjust to the changing landscape of international trade and investment [4, 8]. In response to increased economic uncertainty, countries such as Vietnam and Malaysia have emerged as key actors due to their strategic policy initiatives and advantageous geographic positioning [5, 7]. Vietnam, in particular, has benefitted notably from manufacturers seeking to diversify production bases amidst uncertainties arising from US–China trade frictions [6]. The Vietnamese government has actively implemented economic reforms to improve its business environment, coupled with proactive engagement in multilateral trade agreements like the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), significantly enhancing its appeal as a regional production hub [4, 5]. Meanwhile, Malaysia has strategically positioned itself as a key node within the semiconductor and high-tech sectors by prioritizing technological upgrades and robust industrial policies. This strategic orientation has successfully attracted substantial investments from global technology firms seeking stable alternative production bases [7]. Additionally, Malaysia’s active involvement in regional trade arrangements, including RCEP, further solidifies its regional economic influence [8]. Despite these positive developments, significant challenges persist. Both Vietnam and Malaysia confront ongoing issues such as inadequate infrastructure, skilled labor shortages, and geopolitical pressures from larger economic powers. Addressing these concerns effectively requires well-calibrated policy strategies, coupled with enhanced regional collaboration within ASEAN, to ensure sustainable economic growth and mitigate associated geopolitical and economic risks [9, 14].

4. Case studies: role enhancement of Vietnam and Malaysia

4.1. Vietnam’s strategic role enhancement

Vietnam has witnessed remarkable growth as a key manufacturing hub due to its competitive labor costs, favorable policy environment, and proactive international economic integration [6]. In recent years, major global firms have accelerated the relocation of their manufacturing bases to Vietnam, particularly within electronics and textile sectors, driven by uncertainties surrounding US–China trade relations. Notably, firms such as Samsung, Intel, and Apple suppliers have significantly expanded their production footprints in Vietnam, reinforcing the country’s role as a pivotal node in regional and global supply chains [5]. To support this shift, the Vietnamese government has implemented strategic economic reforms aimed at enhancing the country’s attractiveness to foreign investors. Initiatives like simplifying investment procedures, improving infrastructure connectivity, and participation in key trade agreements (e.g., CPTPP, RCEP, and EU–Vietnam FTA) have markedly strengthened Vietnam’s investment environment, contributing to robust economic growth and industrial upgrading [4, 5]. Nevertheless, Vietnam’s rapid growth has exposed structural vulnerabilities. Infrastructure development has not kept pace with industrial expansion, leading to bottlenecks in logistics and transportation. Moreover, the shortage of skilled labor and limited domestic innovation capabilities pose critical long-term challenges, potentially constraining future industrial upgrading efforts [6].

4.2. Malaysia’s strategic role enhancement

Malaysia has strategically repositioned itself within higher-value segments of global supply chains, particularly in the semiconductor and electronics industries [7]. As a well-established hub for high-tech manufacturing, Malaysia has attracted significant investments from leading multinational corporations such as Intel, Infineon, and Broadcom. Leveraging its existing infrastructure, skilled labor force, and favorable government policies, Malaysia has successfully transitioned towards advanced manufacturing and increased its integration into global high-value-added production networks [8]. Key policy initiatives underpinning Malaysia’s industrial upgrading include targeted incentives for research and development, enhanced investment in technical education, and participation in strategic regional agreements, notably the RCEP. These measures have collectively reinforced Malaysia’s competitive advantages, allowing it to serve as a reliable alternative to traditional production bases in China [7]. However, Malaysia faces substantial challenges in maintaining this growth trajectory. The semiconductor sector’s heavy reliance on imported materials and technologies exposes the country to global supply disruptions. Furthermore, geopolitical tensions between major economic powers create uncertainties regarding long-term stability, potentially undermining investor confidence. Thus, Malaysia must continuously strengthen domestic innovation, diversify supply sources, and strategically manage its international economic partnerships to sustain its competitive position [8, 14].

4.3. Comparative insights: Vietnam and Malaysia

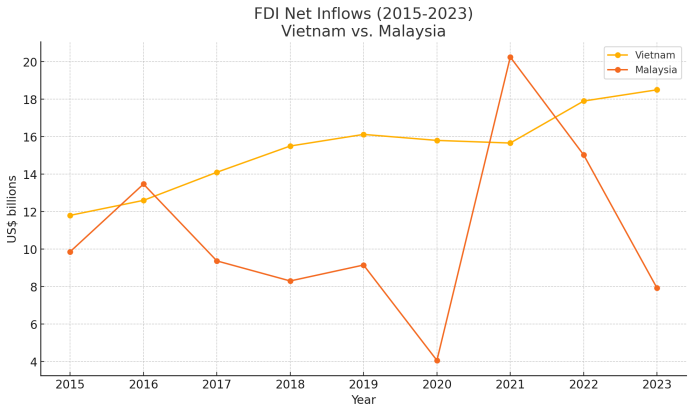

Vietnam leverages low production costs and an expanding network of multilateral trade agreements to attract export-oriented FDI, whereas Malaysia draws on its deeper technological base and long-established electronics ecosystem to capture higher value-added segments of the semiconductor chain [7]. Vietnam’s policy mix—streamlined investment approvals combined with accession to the CPTPP and RCEP—has lured global electronics and garment assemblers into mid-stream manufacturing. By contrast, Malaysia’s targeted R&D incentives and skilled-labour programmes have strengthened upstream capabilities, enabling domestic firms to move into design, testing and packaging. Infrastructure deficits and skill shortages constrain both economies, yet in different ways: Vietnam’s logistics bottlenecks raise trade costs, whereas Malaysia’s dependence on imported equipment and its exposure to major-power chip policies pose greater vulnerabilities. Strategically, Vietnam hedges by accelerating broad-based supply-chain integration, while Malaysia prioritises technological upgrading to reduce reliance on any single market. This comparison underscores a central insight: cost-driven insertion and capability-driven upgrading constitute two distinct—yet potentially complementary—trajectories through which Southeast Asian economies navigate intensifying US–China economic tensions.As Figure 1 illustrates, Vietnam’s FDI inflows climbed steadily from USD 11.8 billion in 2015 to USD 18.5 billion in 2023, whereas Malaysia experienced a sharp “V-shaped” trajectory—bottoming at USD 4.1 billion in 2020 and spiking to USD 20.3 billion in 2021 before tapering off (see Figure 1).

5. Challenges and risks behind the enhancement

Despite significant opportunities presented by evolving US–China economic relations, Vietnam and Malaysia encounter multiple challenges and potential risks accompanying their enhanced strategic roles in regional supply chains. First, both countries face considerable infrastructure limitations, particularly in transportation and logistics, which can hinder effective integration into global production networks. Vietnam’s infrastructure has lagged behind the rapid industrial growth, resulting in increased logistics costs and potential delays in the movement of goods [6]. Malaysia, although possessing relatively developed infrastructure, must continually upgrade its logistics and transportation networks to sustain efficiency in its high-tech manufacturing sector [7]. Second, the availability of skilled labor remains a persistent issue. Vietnam struggles with shortages of adequately trained technical personnel, impeding its capacity to fully benefit from technology transfers and industrial upgrading [5]. Similarly, Malaysia’s semiconductor and electronics industries require sustained investments in workforce training and technical education to meet the increasing demand for skilled labor in high-tech sectors [8]. Third, geopolitical uncertainties present a critical long-term risk. Both Vietnam and Malaysia must carefully balance their economic relations with major global powers, navigating the complexities of international politics without becoming overly dependent on any single partner [14]. This strategic balancing act requires continuous diplomatic skill and policy agility, as mismanagement could result in economic or political repercussions detrimental to their national interests. Finally, both countries face the risk of dependency on external demand and investment, which makes their economies vulnerable to global economic shocks and policy changes in major markets, such as the United States and China [9]. This external reliance underscores the necessity for developing robust domestic innovation ecosystems and diversifying international economic relationships to mitigate risks associated with global market fluctuations. In sum, Vietnam and Malaysia must proactively address these critical challenges through strategic policy interventions, infrastructure development, human capital enhancement, and diplomatic agility to sustain their economic growth trajectories and geopolitical relevance in an uncertain global economic landscape.

6. Responses and policy recommendations

In response to the evolving landscape shaped by US–China economic dynamics, Vietnam and Malaysia need to adopt multifaceted strategic policy approaches to effectively manage both opportunities and risks associated with their enhanced roles in regional supply chains. First, strategic balancing should remain a cornerstone of their foreign economic policies. Both nations need to maintain diversified trade and investment partnerships, thus reducing their vulnerability to disruptions in relations with any single global power [14]. Establishing balanced and pragmatic relations with the United States, China, and other major economic partners will be crucial in preserving their strategic autonomy and economic stability. Second, infrastructure development must become a high priority. Vietnam should prioritize targeted investments in ports, roads, railways, and logistical facilities to alleviate existing bottlenecks and enhance the efficiency of its supply chain operations [6]. Malaysia, likewise, needs sustained infrastructure modernization efforts, especially in areas supporting high-tech industries, such as telecommunications and digital infrastructure, to solidify its competitive advantage in advanced manufacturing [7]. Third, addressing the skilled labor shortage through comprehensive human capital development programs is essential. Vietnam should strengthen vocational training programs, improve collaboration with industry stakeholders, and facilitate technology transfers to enhance workforce capabilities [5]. Malaysia, similarly, should focus on advanced technical education and promote continuous professional development initiatives to ensure a steady pipeline of highly skilled talent supporting its high-value-added industries [8].

Fourth, fostering innovation and developing robust domestic industries will mitigate external dependency risks. Vietnam and Malaysia should provide incentives for research and development activities, encourage collaborations between academic institutions and industries, and support domestic startups and technology enterprises [6, 7]. Strengthening domestic innovation capacity will reduce vulnerabilities to global market fluctuations and geopolitical uncertainties.

Finally, enhanced regional cooperation within ASEAN should be pursued. Closer intra-regional economic collaboration, coordinated investment strategies, and harmonized regulatory frameworks can significantly strengthen Southeast Asia’s collective bargaining position and resilience in the global economic arena [9]. Active engagement in regional initiatives such as RCEP can further bolster their integration and economic security. By systematically addressing these policy areas, Vietnam and Malaysia can effectively navigate complexities posed by evolving US–China relations, capitalize on emerging economic opportunities, and reinforce their strategic economic resilience.

7. Conclusion

This study has examined the significant transformations in regional supply chains within Southeast Asia in response to evolving economic relations between the United States and China, focusing specifically on the strategic roles of Vietnam and Malaysia. Utilizing Geo-economics and Global Value Chain theories, the analysis highlighted how these countries have effectively leveraged shifting production and investment patterns to enhance their economic positions and geopolitical agency [11, 12]. Vietnam has successfully attracted substantial foreign investment through competitive labor costs, strategic reforms, and active integration into global trade networks [6]. Malaysia has similarly positioned itself strategically within the global semiconductor and electronics sectors, achieving considerable industrial upgrading and economic diversification [7]. However, these advancements are accompanied by notable challenges, including infrastructure deficits, skilled labor shortages, geopolitical pressures, and vulnerabilities stemming from external economic dependency [8, 9]. To address these challenges and sustain their enhanced roles, Vietnam and Malaysia must prioritize strategic balancing, infrastructure modernization, comprehensive human capital development, domestic innovation promotion, and strengthened regional cooperation within ASEAN [7, 14]. Implementing these policy recommendations will be essential for both nations to effectively manage opportunities and risks within the rapidly evolving global economic landscape.This research underscores the importance of proactive, coordinated, and strategically balanced policies to ensure that Southeast Asian nations not only adapt to global economic shifts but also thrive amid growing geopolitical complexities. Future research should further investigate the long-term impacts of these strategic shifts on regional economic stability and geopolitical dynamics.

References

[1]. Baldwin, R., & Evenett, S. J. (2020). COVID-19 and Trade Policy: Why Turning Inward Won’t Work. CEPR Press.

[2]. Blackwill, R. D., & Harris, J. M. (2016). War by Other Means: Geoeconomics and Statecraft. Harvard University Press.

[3]. Chen, L., & Woo, W. T. (2020). US-China Trade War: The Implications for ASEAN. Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia.

[4]. Das, S. B., & Teng, F. (2020). US–China Decoupling: ASEAN Caught in Between. ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute.

[5]. Farrell, H., & Newman, A. L. (2020). Chained to Globalization: Why It’s Too Late to Decouple.Foreign Affairs, 99(1), 70–80.

[6]. Gereffi, G., & Fernandez-Stark, K. (2016). Global Value Chain Analysis: A Primer (2nd ed.). Duke University Center on Globalization, Governance & Competitiveness.

[7]. Goh, E. (2016). Southeast Asian Strategies Toward the Great Powers: Still Hedging After All These Years?The ASAN Forum, 4(1), 1–12.

[8]. Le Hong Hiep. (2021). Vietnam’s Response to US–China Strategic Rivalry.Asian Politics & Policy, 13(4), 583–598.

[9]. Menon, J. (2022). ASEAN’s Economic Resilience in the Face of US-China Trade Tensions.Asian Economic Policy Review, 17(1), 16–32.

[10]. Nguyen, H. Q. (2021). Vietnam’s Economic Growth and Foreign Direct Investment Attraction Amid US-China Trade Conflict.Journal of Asian Business Strategy, 11(1), 30–42.

[11]. Ponte, S., & Sturgeon, T. (2014). Explaining Governance in Global Value Chains: A Modular Theory-building Effort.Review of International Political Economy, 21(1), 195–223.

[12]. Rasiah, R. (2022). Malaysia’s Electronics Industry in Global Value Chains.Journal of Contemporary Asia, 52(2), 289–312.

[13]. Scholvin, S., & Wigell, M. (2018). Geo-economic Power Politics: An Introduction. In Wigell, M., Scholvin, S., & Aaltola, M. (Eds.), Geo-economics and Power Politics in the 21st Century. Routledge.

[14]. Yeung, H. W. C., & Coe, N. M. (2015). Toward a Dynamic Theory of Global Production Networks.Economic Geography, 91(1), 29–58.

[15]. Acharya, A. (2021). ASEAN and Regional Order: Revisiting Security Community in Southeast Asia.Asian Survey, 61(1), 86–108.

[16]. Athukorala, P. C. (2019). Southeast Asia in Global Production Networks.Asian Economic Policy Review, 14(1), 32–50.

[17]. Cai, K. G. (2018). The Political Economy of East Asia: Regional and National Dimensions. Palgrave Macmillan.

[18]. Cook, M. (2021). Southeast Asia’s Geopolitical Dynamics amid US-China Rivalry.Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 40(1), 29–51.

[19]. Dent, C. M. (2018). East Asian Integration: Towards an East Asian Economic Community?Asian Survey, 58(4), 707–729.

[20]. Emmers, R., & Teo, S. (2019). Security Strategies of Middle Powers in the Asia-Pacific.Asian Security, 15(1), 60–77.

[21]. Kimura, F. (2020). ASEAN and Production Networks in Southeast Asia.Asian Economic Policy Review, 15(2), 181–199.

[22]. Kuik, C.-C. (2020). Hedging in Post-Pandemic Asia: What, How, and Why?The Pacific Review, 33(6), 986–1009.

[23]. Le Hong Hiep. (2020). Foreign investors exiting China: Vietnam milks the gains. ISEAS Perspective No. 2020/65. ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute.

[24]. Liow, J. C. (2021). Strategic Balancing, Hedging, and Aligning: The Case of Southeast Asia.International Affairs, 97(5), 1549–1567.

[25]. Nesadurai, H. E. S. (2019). ASEAN during the life of the Pacific Rim: Regionalism, institutions and political economy.Journal of Contemporary Asia, 49(2), 290–307.

[26]. Pempel, T. J. (2020). Regional Order in East Asia: A Geopolitical and Economic Perspective.Asian Survey, 60(4), 649–671.

[27]. Petri, P. A., & Plummer, M. G. (2020). RCEP: A new trade agreement that will shape global economics and politics. Brookings Institution, Policy Brief, 1–8.

[28]. Rasiah, R., & Wong, S. H. (2021). Industrial upgrading in the semiconductor industry in East Asia.Innovation and Development, 11(2–3), 413–440.

[29]. Storey, I., & Cook, M. (Eds.). (2019). Southeast Asia and the Great Powers: Continuity and Change. Routledge.

[30]. Stubbs, R. (2019). ASEAN’s Strategic Position in East Asia.Contemporary Southeast Asia, 41(3), 321–343.

[31]. Yoshimatsu, H. (2021). East Asian Regionalism and Southeast Asia’s Roles.The Pacific Review, 34(2), 199–225.

[32]. Zhu, Z. (2021). China–ASEAN Relations: Strategic Competition or Strategic Partnership?East Asia, 38(2), 123–140.

Cite this article

Qiao,X.;Wang,J. (2025). Reconfiguring regional supply chains: Southeast Asia amid evolving US–China economic relations. Journal of Applied Economics and Policy Studies,18(6),52-56.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Journal of Applied Economics and Policy Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Baldwin, R., & Evenett, S. J. (2020). COVID-19 and Trade Policy: Why Turning Inward Won’t Work. CEPR Press.

[2]. Blackwill, R. D., & Harris, J. M. (2016). War by Other Means: Geoeconomics and Statecraft. Harvard University Press.

[3]. Chen, L., & Woo, W. T. (2020). US-China Trade War: The Implications for ASEAN. Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia.

[4]. Das, S. B., & Teng, F. (2020). US–China Decoupling: ASEAN Caught in Between. ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute.

[5]. Farrell, H., & Newman, A. L. (2020). Chained to Globalization: Why It’s Too Late to Decouple.Foreign Affairs, 99(1), 70–80.

[6]. Gereffi, G., & Fernandez-Stark, K. (2016). Global Value Chain Analysis: A Primer (2nd ed.). Duke University Center on Globalization, Governance & Competitiveness.

[7]. Goh, E. (2016). Southeast Asian Strategies Toward the Great Powers: Still Hedging After All These Years?The ASAN Forum, 4(1), 1–12.

[8]. Le Hong Hiep. (2021). Vietnam’s Response to US–China Strategic Rivalry.Asian Politics & Policy, 13(4), 583–598.

[9]. Menon, J. (2022). ASEAN’s Economic Resilience in the Face of US-China Trade Tensions.Asian Economic Policy Review, 17(1), 16–32.

[10]. Nguyen, H. Q. (2021). Vietnam’s Economic Growth and Foreign Direct Investment Attraction Amid US-China Trade Conflict.Journal of Asian Business Strategy, 11(1), 30–42.

[11]. Ponte, S., & Sturgeon, T. (2014). Explaining Governance in Global Value Chains: A Modular Theory-building Effort.Review of International Political Economy, 21(1), 195–223.

[12]. Rasiah, R. (2022). Malaysia’s Electronics Industry in Global Value Chains.Journal of Contemporary Asia, 52(2), 289–312.

[13]. Scholvin, S., & Wigell, M. (2018). Geo-economic Power Politics: An Introduction. In Wigell, M., Scholvin, S., & Aaltola, M. (Eds.), Geo-economics and Power Politics in the 21st Century. Routledge.

[14]. Yeung, H. W. C., & Coe, N. M. (2015). Toward a Dynamic Theory of Global Production Networks.Economic Geography, 91(1), 29–58.

[15]. Acharya, A. (2021). ASEAN and Regional Order: Revisiting Security Community in Southeast Asia.Asian Survey, 61(1), 86–108.

[16]. Athukorala, P. C. (2019). Southeast Asia in Global Production Networks.Asian Economic Policy Review, 14(1), 32–50.

[17]. Cai, K. G. (2018). The Political Economy of East Asia: Regional and National Dimensions. Palgrave Macmillan.

[18]. Cook, M. (2021). Southeast Asia’s Geopolitical Dynamics amid US-China Rivalry.Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 40(1), 29–51.

[19]. Dent, C. M. (2018). East Asian Integration: Towards an East Asian Economic Community?Asian Survey, 58(4), 707–729.

[20]. Emmers, R., & Teo, S. (2019). Security Strategies of Middle Powers in the Asia-Pacific.Asian Security, 15(1), 60–77.

[21]. Kimura, F. (2020). ASEAN and Production Networks in Southeast Asia.Asian Economic Policy Review, 15(2), 181–199.

[22]. Kuik, C.-C. (2020). Hedging in Post-Pandemic Asia: What, How, and Why?The Pacific Review, 33(6), 986–1009.

[23]. Le Hong Hiep. (2020). Foreign investors exiting China: Vietnam milks the gains. ISEAS Perspective No. 2020/65. ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute.

[24]. Liow, J. C. (2021). Strategic Balancing, Hedging, and Aligning: The Case of Southeast Asia.International Affairs, 97(5), 1549–1567.

[25]. Nesadurai, H. E. S. (2019). ASEAN during the life of the Pacific Rim: Regionalism, institutions and political economy.Journal of Contemporary Asia, 49(2), 290–307.

[26]. Pempel, T. J. (2020). Regional Order in East Asia: A Geopolitical and Economic Perspective.Asian Survey, 60(4), 649–671.

[27]. Petri, P. A., & Plummer, M. G. (2020). RCEP: A new trade agreement that will shape global economics and politics. Brookings Institution, Policy Brief, 1–8.

[28]. Rasiah, R., & Wong, S. H. (2021). Industrial upgrading in the semiconductor industry in East Asia.Innovation and Development, 11(2–3), 413–440.

[29]. Storey, I., & Cook, M. (Eds.). (2019). Southeast Asia and the Great Powers: Continuity and Change. Routledge.

[30]. Stubbs, R. (2019). ASEAN’s Strategic Position in East Asia.Contemporary Southeast Asia, 41(3), 321–343.

[31]. Yoshimatsu, H. (2021). East Asian Regionalism and Southeast Asia’s Roles.The Pacific Review, 34(2), 199–225.

[32]. Zhu, Z. (2021). China–ASEAN Relations: Strategic Competition or Strategic Partnership?East Asia, 38(2), 123–140.