1. Introduction

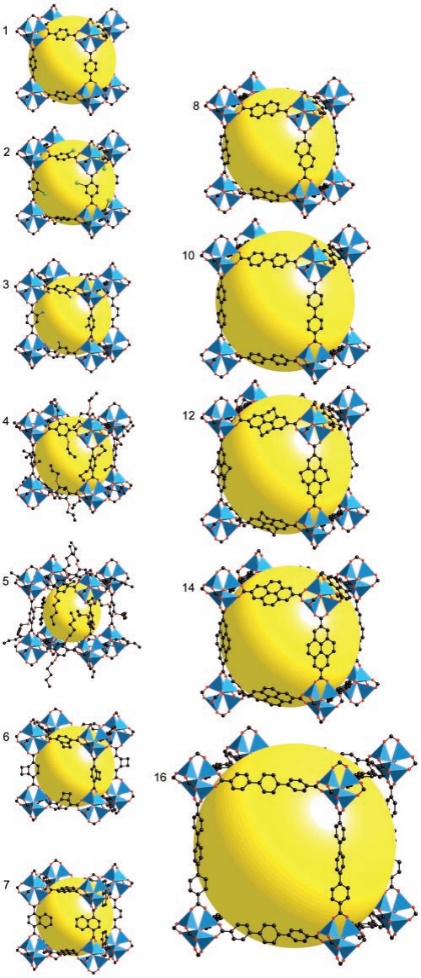

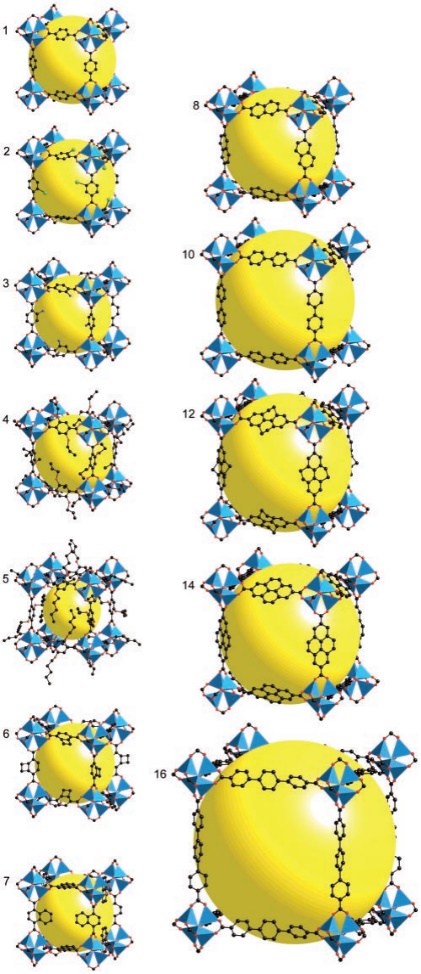

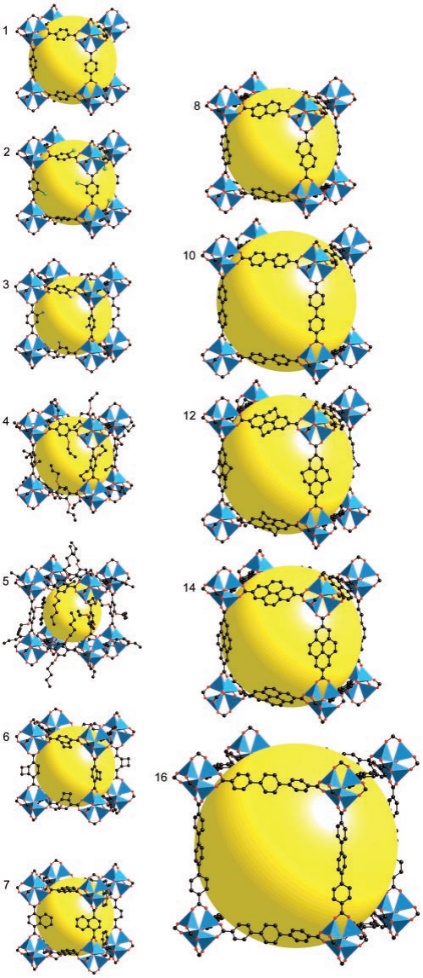

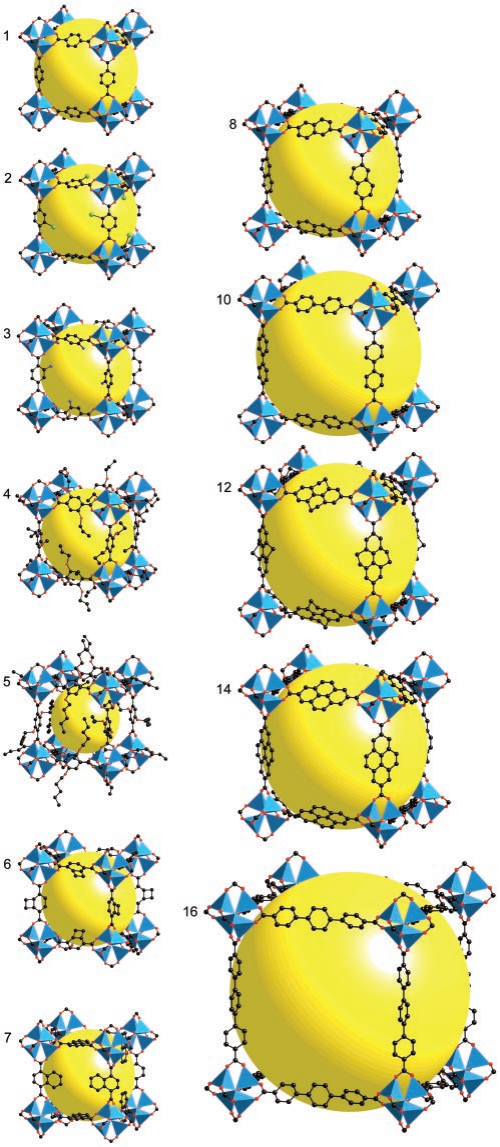

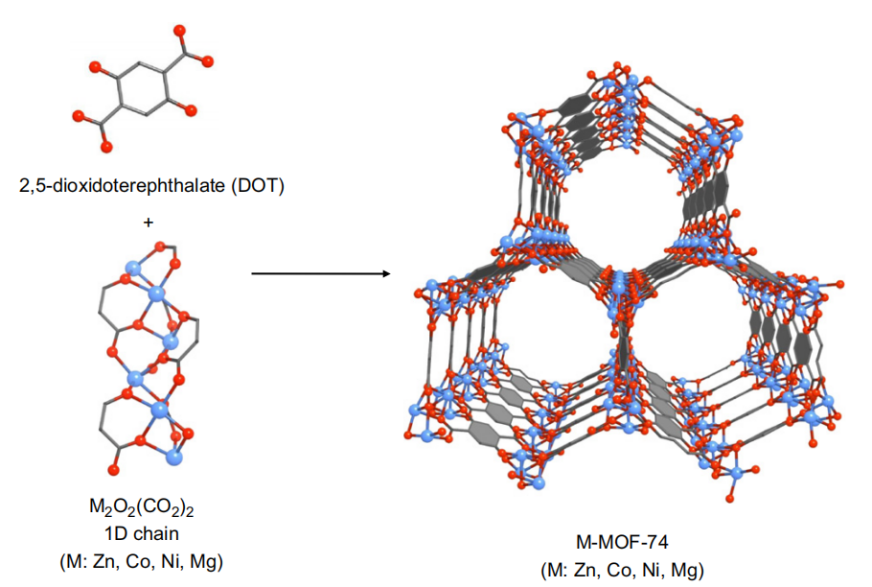

MOFs are special materials made by sticking metal bits and organic parts together. They've become popular because of the way metal and organic stuff can team up. These materials have lots of little holes and special spots that can do various things. Scientists use them to store gases and make reactions happen. The way MOFs are built is like putting together pieces of a puzzle. The metal parts and organic parts fit together to make different shapes and sizes. This makes MOFs flexible and useful for different tasks. For example, by changing the size of the pieces, scientists can adjust how much stuff the MOF can hold. Imagine MOFs as buildings with rooms that can do special things. The way the rooms are built, and the materials used can make them strong or weak [8]. Some MOFs are better at handling water and heat because of how they're built. Scientists can even change the metal parts to make the rooms interact differently with gases, which is handy for certain tasks. In simple words, MOFs are like versatile tools that scientists use to store things and make reactions go smoothly. They're like Lego sets that can be put together in different ways to do different jobs, like holding stuff or reacting with gases. The ability to adjust both structure and function lets MOFs work together by using their pores and special spots. This helps them increase the amount of gas they can hold while also separating different gases using various methods like thermodynamic sieving, kinetic sieving, gate-opening effects, and molecular sieving [9-11]. Additionally, to better understand the versatile nature of MOF materials, it is essential to explore their structural diversity. Figure 1 illustrates the crystal structures of IRMOF-n (n=1-8, 10, 12, 14, 6) with various ligands, showcasing the intricate arrangements of metal and organic components. This diversity in structure allows MOFs to exhibit unique properties tailored for specific applications. Moreover, Figure 2 provides a schematic representation of the formation of M-MOF-74 (M: Zn, Co, Ni, Mg), shedding light on the synthesis process and emphasizing the importance of metal selection in designing MOFs. There are five categories of MOF applications, including Carbon dioxide capture, Adsorption and Purification of CH4, Separation of C2H2/C2H4, Separation of C2H4/C2H6, and Separation of C3H6/C3H8 by adsorption.

Figure 1. The crystal structures of IRMOF-n(n=1-8101214,6) with different ligands [4]

Figure 2. Schematic representation of the formation of M-MOF-74 (M: Zn, Co, Ni, Mg) [5]

2. Carbon Dioxide Capture

Carbon dioxide is a major greenhouse gas. In recent years, researchers have been using a new type of material called Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) to capture CO2 from the air. These MOFs have adjustable structures and functions, making them effective adsorbents for capturing CO2 [6-8]. One type of MOF called SIFUSIX-MOFs contains silicon and other elements. They have a special structure that makes them excellent at capturing CO2 compared to other gases. In the year 2013, Nugent and colleagues have been studying different SIFUSIX-MOFs to understand their ability to capture CO2. They found that SiFUSIX-3-Zn has the best performance in terms of capturing CO2, showing high CO2 adsorption even at certain temperatures and pressures [9] (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. (a) The structures and ligands of SIFSIX-2-Cu, SIFSIX-2-Cu-i, and SIFSIX-3-Zn; (b) CO2 adsorption isotherms of SIFSIX-2-Cu-i at different temperatures; (c) CO2 adsorption isotherms of SIFSIX-3-Zn at different temperatures [10]

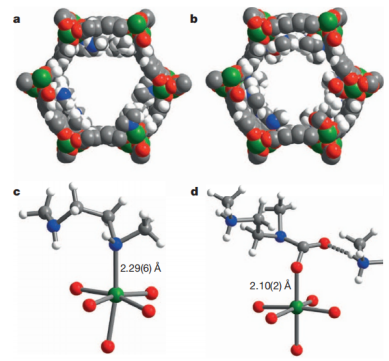

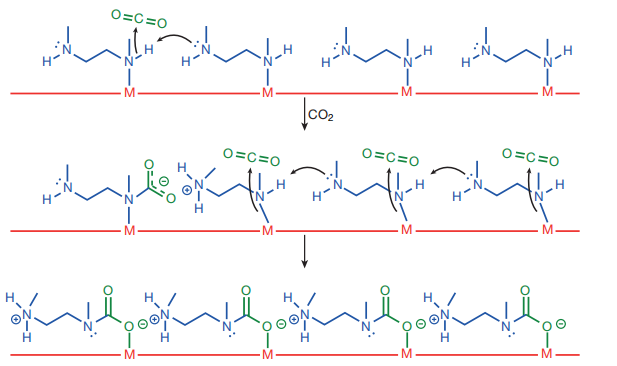

It's also good at selectively separating CO2 from other gases, which is important for various applications. To make these materials more practical, researchers are trying to improve their sensitivity to water and maintain their adsorption capacity even in humid conditions [11]. In the year 2016, Chen and colleagues even modified the MOFs with specific chemical groups to enhance their ability to selectively capture CO2. In one study, researchers attached certain groups to the surface of the MOFs to create a more efficient way of capturing CO2 [12-14]. They observed interesting changes in CO2 adsorption, suggesting that a special process happens when CO2 is captured (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. At 100K, the solid filling models of mmen-Mn2(dobpdc) (2) and CO2-mmen-Mn2(dobpdc) (b); before (c) and after (d) CO2 adsorption, partial crystal structure of mmen-Mn2(dobpdc) (e); CO2 cooperative adsorption mechanism [15]

3. Adsorption and Purification of CH4

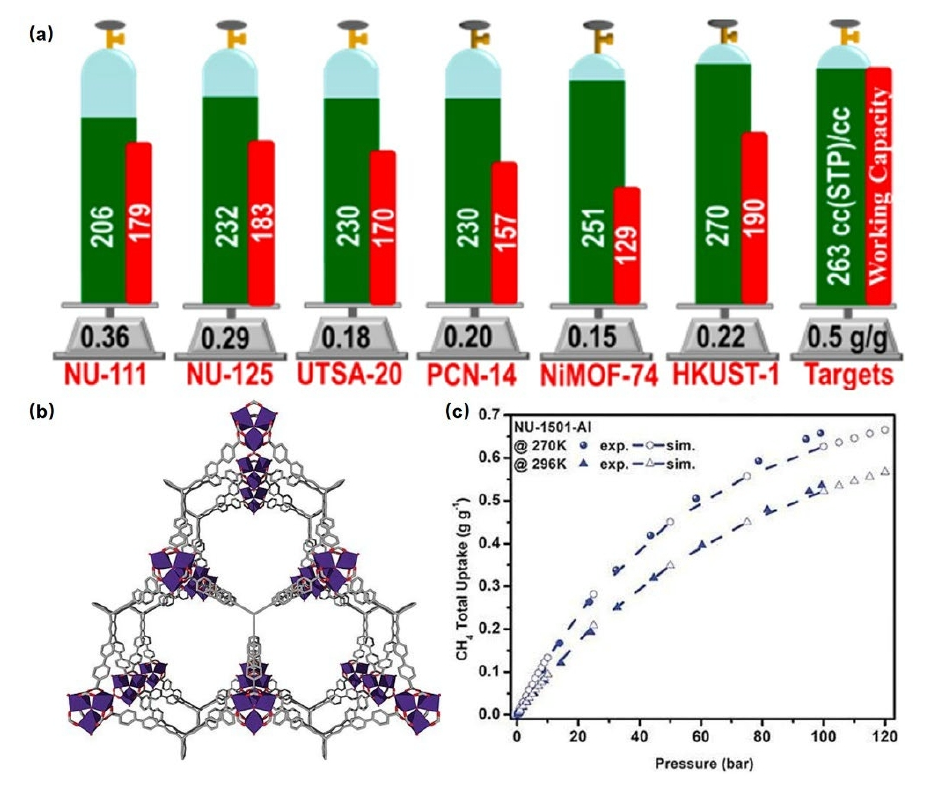

Methane (CH4) is an important component of natural gas, which is used for clean energy and in making various chemicals. In the past, when we tried to purify methane, we faced challenges because it had extra CO2 and other gases mixed in. These impurities made it difficult to use methane effectively. To solve this, researchers are looking into new materials called MOFs (Metal-Organic Frameworks) that can help clean up methane and remove those unwanted gases. In the year 2013, the research group led by O. K. Farha studied different types of MOFs to see which ones can capture and hold methane the best [16]. They found that the size of the pores in the MOFs and their surface area play a big role in how well they can capture methane [17]. They also discovered new MOFs that have super high surface area and can capture a lot of methane (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. (a) CH4 adsorption capacities for a series of classic MOFs (PCN-14, UTSA-20, HKUST-1, Ni-MOF-74, Ni-CPO27, NU-111, and NU-125) under 65 bar conditions, along with their working capacities (difference in uptake between two pressures) and comparison to the U.S. Department of Energy standards [31]; (b) Structural diagram of NU-1501; (c) Mass adsorption isotherms of CH4 on NU-1501-Al at different temperatures [17].

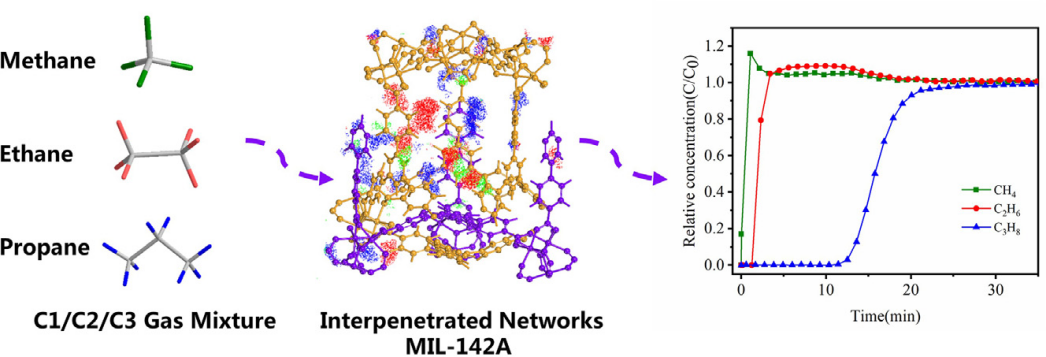

One group of researchers created a MOF that can separate different gases from methane. For example, they made a MOF that can separate propane (C3H8) and ethane (C2H6) from methane [18]. This is important because sometimes, we want to use only the purest form of methane for different processes. They found that this new material can separate these gases well, which is helpful for industries (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Schematic diagram of gas separation with C1/C2/C3 ternary components using MIL-142A [18]

Another group of researchers made a MOF with a special structure that has tiny pockets where methane can stick [19]. This MOF is good at separating methane from other gases like nitrogen (N2) or ethane. The special design of this material makes it a great candidate for cleaning up methane for various uses. In summary, people are working on finding new materials (MOFs) that can help us clean up methane and make it pure for different purposes. These materials have tiny spaces that can trap methane and separate it from other gases, making methane more valuable for clean energy and chemical production.

4. Separation of C2 Hydrocarbon

4.1. Separation of C2H2/C2H4

Ethylene (C2H4) is one of the most widely used alkenes, crucial in the petrochemical industry. However, during production, it's common to have ethyne (C2H2) present in the ethylene mixture, which is harmful to the catalyst used in ethylene polymerization. Therefore, it's necessary to separate C2H2 from C2H4. Yet, their similar physical properties make this separation challenging [20-22]. The current methods, like low-temperature distillation and solvent extraction, are expensive and energy-consuming. People are exploring a more energy-efficient approach using porous materials for adsorption separation. In 2016, a research group led by Cui investigated several MOFs (Metal-Organic Frameworks) for C2H2/C2H4 separation [23, 24] (see Figure 7). These MOFs showed better adsorption performance for C2H2 compared to C2H4. Among them, Cu-I-based MOF (SIFSIX-2-Cu-i) exhibited a promising adsorption capacity of 2.1 mmol/g for C2H2 under 298 K and 0.025 bar, along with a high selectivity of 39.7-44.8 for C2H2/C2H4 separation. The unique interaction between each C2H2 molecule and the framework, facilitated by hydrogen bonding with different F atoms in the network, contributes to the exceptional adsorption performance and selectivity.

Figure 7. (a) Isotherms of C2H2 (circles) and C2H4 (triangles) in SIFSIX-1-Cu (red), SIFSIX-2-Cu (green), SIFSIX-2-Cu-I (blue), SIFSIX-3-Zn (light blue), and SIFSIX-3-Ni (orange) at 298K; (b) IAST (Ideal Adsorbed Solution Theory) selectivity comparison of 1% C2H2 mixture in SIFSIX materials with other C2H2/C2H4 separation MOFs; (c) Permeation simulation; (d) Comparative energy analysis with other MOFs [23]

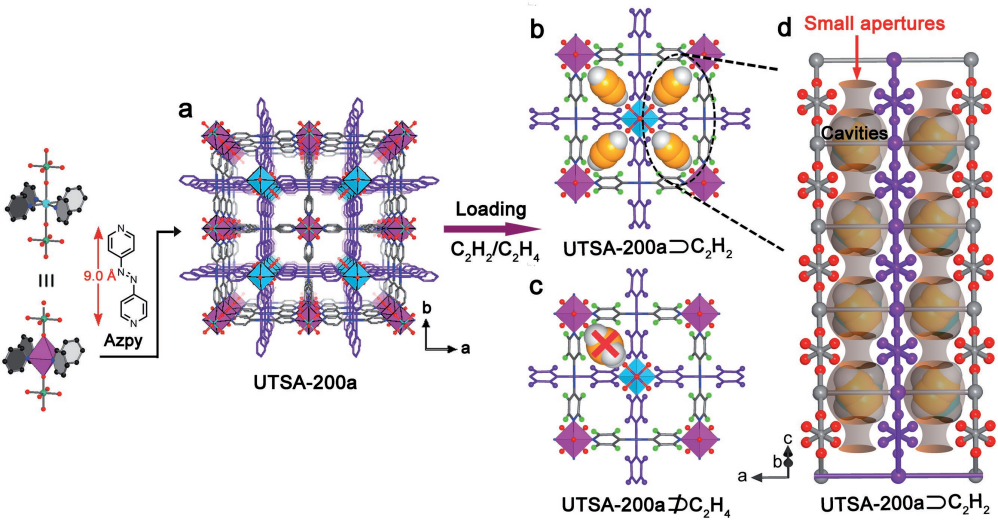

In 2018, Li and their team focused on various MOFs for C2H2/C2H4 separation. A MOF with a pore size of 3.4 Å called SIFSIX-14-Cu-i (UTSA-200a) showed the best performance [25] (see Figure 8).

Figure 8. (a) The crystal structure of UTSA-200a; Theoretical models for C2H2 (b) and C2H4 (c) adsorption in UTSA-200a; (d) Crystal structure of C2H2 in UTSA-200a [25]

Its compact pore size perfectly matched C2H2 molecules while blocking larger C2H4. This structural advantage allowed UTSA-200a to achieve a high adsorption capacity of 116 cm³/cm³ under 298 K and 1 bar for C2H2. Its remarkable performance also extended to a C2H2/C2H4 mixture, where it displayed an impressive Ideal Adsorption Solution Theory (IAST) selectivity of over 6000 at the same conditions. In summary, researchers have been working on efficient methods to separate C2H2 from C2H4 mixtures. Using advanced materials like MOFs, they have achieved impressive results in terms of adsorption capacity and selectivity. This progress is significant for industrial processes that require pure ethylene while minimizing energy consumption.

4.2. Separation of C2H4/C2H6

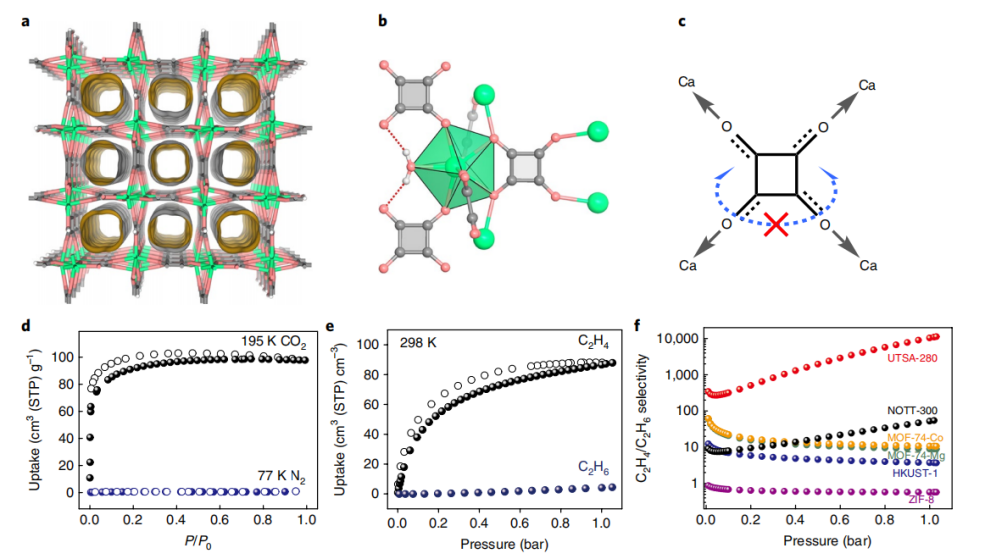

The separation of ethene (C2H4) from ethane (C2H6) is an important industrial process used in the petrochemical industry. In the year 2018, Lin and colleagues found a way to precisely adjust the pore size of MOFs (Metal-Organic Frameworks) to separate C2H4 from C2H6, targeting this specific separation challenge. In 2018, researchers led by Lin developed a type of super microporous MOF called Ca(C4O4) (H2O) (UTSA-280M), with a one-dimensional rigid pore structure measuring about 3.8 Å x 3.8 Å. This pore size aligns perfectly with the smallest cross-sections of C2H4 (13.7 Å) and C2H6 (15.5 Å) (see Figure 9), allowing C2H4 to pass through while preventing C2H6 transport, achieving an ideal separation. UTSA-280M was proven through experiments to efficiently separate C2H4 from C2H6 under conditions of 298 K and 1 bar, with a high C2H4 production rate. Moreover, UTSA-280M is water-stable and can be easily prepared on a kilogram scale using environmentally friendly methods, making it a valuable candidate for industrial applications.

Figure 9. (a) Crystal structure of UTSA-280. Green, light coral and gray nodes represent Ca, O, and C atoms, respectively; (b) Coordination environment of formate ligand and calcium ion; (c) Coordination constraints of C4O4-2 ligand; (d) Single-component adsorption isotherms of CO2 (black) at 195K, N2 (blue) at 77K, ethene (black) and ethane (indigo) at 298K; (e) IAST (Ideal Adsorbed Solution Theory) adsorption selectivity comparison for equimolar ethene/ethane mixture among different MOFs at 298K [26]

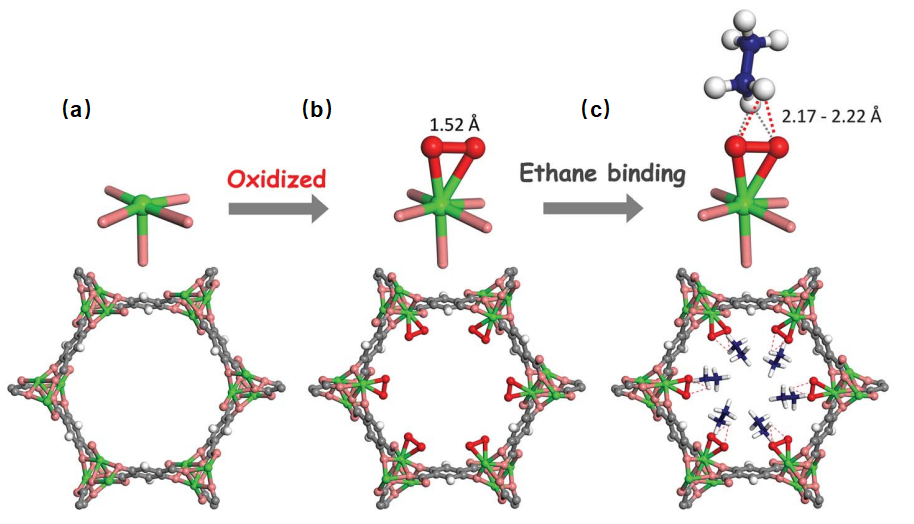

In industrial production, obtaining high-purity C2H4 requires the removal of small amounts of C2H6. MOFs like UTSA-280M, with their strong C2H6 adsorption, can potentially lower production costs and energy consumption. In 2018, Li and the team employed a reverse approach by using Fe2(0.2) (dobdc) to create a MOF with strong C2H6 adsorption for efficient C2H6/C2H4 separation [27] (see Figure 10).

Figure 10. (a) Crystal structure of Fe2(dobdc); (b) Crystal structure of Fe2(O2) (dobdc); (c) Crystal structure of Fe2(O2)(dobdc)C2D6. Iron atoms are represented in green; Carbon in deep gray; Oxygen in pink; O22- in red; Hydrogen or Deuterium in white; Carbon in C2D6 in blue [27]

Overall, researchers are exploring innovative methods to achieve efficient separation of C2H4 from C2H6 using MOFs with tailored pore sizes. These advancements hold the potential to revolutionize industrial processes while reducing environmental impact.

5. Separation of C3H6/C3H8 by Adsorption

The separation of C3H6/C3H8 is a crucial and challenging industrial process [28-30]. MOF-74 is a well-known type of MOF with open metal sites (OMS) that can interact effectively with various gases [31]. In 2012, Long and his team investigated the use of Fe-MOF-74 for low-carbon hydrocarbon separation, including C3H6/C3H8 separation [32, 33] (see Figure 11).

Figure 11. (a) Crystal structure of Fe-MOF-74; (b) Interaction modes of OMS, C3H6, and C3H8 in Fe-MOF-74; (c) Adsorption isotherms of C3H6 and C3H8 on Fe-MOF-74 at 318 K [32]

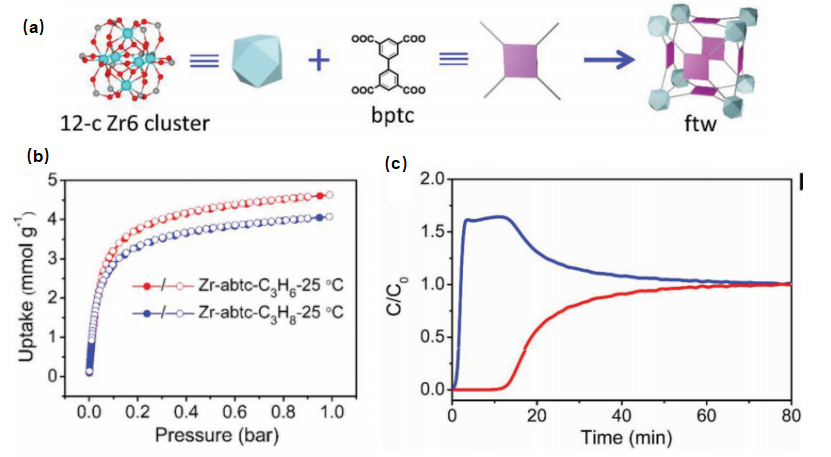

The Fe-MOF-74 could adsorb C3H6 more than C3H8 due to ion-induced dipole interactions. The separation is achieved through coordination with the unsaturated metal cation in the MOF structure. In 2018, Wang and the team used Y-based MOF (Y-abtc) with a pore window size suitable for the kinetic diameter difference between C3H6 (4.68 Å) and C3H8 (5.1 Å) to achieve C3H6 molecular sieving [34] (see Figure 12).

Figure 12. (a) Building units and structure of Y-abtc; (b) Adsorption isotherms of C3H8 and C3H6 on Y-abtc at 25°C; (c) Multicomponent penetration results of equimolar C3H8 and C3H6 mixture on Y-abtc at 25°C [34]

The Y-abtc quickly adsorbs C3H6 while excluding C3H8. Multi-component breakthrough experiments showed that highly pure C3H6 (99.5%) can be obtained from the obtained C3H6/C3H8 mixture. Considering its thermal and hydrothermal stability, as well as its effective C3H6/C3H8 separation, this work demonstrated the potential of Y-abtc as an alternative adsorbent for separating C3H6/C3H8 mixtures. MOFs are promising candidates for gas separation due to their evenly distributed pore sizes, various functional sites, and adjustable pore sizes. Gas separation techniques based on different adsorption mechanisms are being explored and applied to gases like C3H4/C3H6 and others. These techniques have shown promising results in achieving successful gas separation.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, researchers are harnessing the unique properties of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) to address pressing challenges in gas separation and purification. Whether capturing carbon dioxide to combat climate change, purifying methane for clean energy applications, or achieving precise separations of gases like ethylene and ethane, MOFs offer a versatile and innovative solution. Their tunable structures, adjustable pore sizes, and specialized interactions enable them to capture specific gases with impressive efficiency and selectivity. As industries evolve and environmental concerns grow, these advancements in gas separation technology hold significant promise for transforming industrial processes while reducing energy consumption and minimizing environmental impact.

References

[1]. Yu J, Xie L-H, Li J-R, et al.CO2 capture and separations using MOFs: Computational and experimental studies[J]. Chemical Reviews2017117(14): 9674-9754.

[2]. Spanopoulos I, Tsangarakis C, Klontzas E, et al. Reticular synthesis of HKUST-like to-MOFs with enhanced CH4 storage[J]. Journal of the American Chemical Society,2016,138(5): 1568-1574.

[3]. Chen Dandan, Chen Deli, Xu Chunhui, et al. Research progress on the impact of water vapor on the adsorption and separation of mixed gases by MOFs materials [J]. Guangdong Chemical Industry 2017, 44(8): 94-95+126.

[4]. Eddaoudi M, Kim J, Rosi N, et al. Systematic design of pore size and functionality in isoreticular MOFs and their application in methane storage[J]. Science, 2002, 295(5554):469-472.

[5]. Grant Glover T, Peterson G W, Schindler B J, et al. MOF-74 building unit has a direct impact on toxic gas adsorption[J]. Chemical Engineering Science, 2011, 66(2): 163-170.

[6]. Zhang Z, Yao Z-Z, Xiang S, et al. Perspective of microporous metal-organic frameworks for CO2 capture and separation[J]. Energy & Environmental Science, 2014, 7(9): 2868-2899.

[7]. Jiang J, Lu Z, Zhang M, et al. Higher symmetry multinuclear clusters of metal-organic frameworks for highly selective CO capture[J]. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2018,140(51): 17825-17829.

[8]. Jiang Y Tan P, Qi S-C, et al. Metal-organic frameworks with target-specific active sites switched by photoresponsive motifs: Efficient adsorbents for tailorable CO2 capture[J]. Angewandte Chemie International Edition,2019,58(20): 6600-6604.

[9]. Nugent P, Belmabkhout Y, Burd S D, et al. Porous materials with optimal adsorption thermodynamics and kinetics for CO2 separation[J]. Nature, 2013,495: 80-84.

[10]. Nugent P, Belmabkhout Y, Burd S D, et al. Porous materials with optimal adsorption thermodynamics and kinetics for CO2 separation[J]. Nature, 2013, 495: 80-84.

[11]. O’nolan D, Kumar A, Zaworotko M J.Water vapor sorption in hybrid pillared square grid materials[J].Journal of the American Chemical Society2017139(25): 8508-8513

[12]. Chen K-J, Madden D G, Pham T, et al. Tuning pore size in square-lattice coordination networks for size-selective sieving of CO2[J]. Angewandte Chemie International Edition.2016,55(35): 10268-10272.

[13]. [13] Liao P-O, Chen X-W, Liu S-Y, et al. Putting an ultrahigh concentration of amine groups into a metal-organic framework for CO2 capture at low pressures[J]. Chemical Science, 2016.7(10):6528-6533.

[14]. Siegelman R L, Mcdonald T M, Gonzalez M I, et al. Controlling cooperative CO2 adsorption in diamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) metal-organic frameworks[J]. Journal of the American Chemical Society,2017,139(30): 10526-10538.

[15]. Mcdonald T M, Mason J A, Kong X, et al. Cooperative insertion of CO2 in diamine-appended metal-organic frameworks[J]. Nature, 2015,519(7543): 303-308.

[16]. PENG Y, KRUNGLEVICIUTE V, ERYAZICI I, et al. Methane storage in metal–organic frameworks: current records, surprise findings, and challenges [J]. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2013, 135(32): 11887-11894.

[17]. CHEN Z, LI P, ANDERSON R, et al. Balancing volumetric and gravimetric uptake in highly porous materials for clean energy [J]. Science, 2020, 368(6488): 297-303.

[18]. YUAN Y, WU H, XU Y, et al. Selective extraction of methane from C1/C 2/C 3 on moisture-resistant MIL-142A with interpenetrated networks [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2020, 395: 125057.

[19]. TU S, YU L, LIN D, et al. Robust nickel-based metal–organic framework for highly efficient methane purification and capture [J]. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2022, 14(3): 4242-4250.

[20]. Fan C B, Le Gong L, Huang L, et al. Significant enhancement of C2H2/C2H4 separation by a photochromic diarylethene unit: A temperature- and light-responsive deparation switch[J]. Angewandte Chemie International Edition,2017,56(27): 7900-7906.

[21]. Hong X-J, Wei Q, Cai Y-P, et al. Pillar-layered metal-organic framework with sieving effect and pore space partition for effective separation of mixed gas C2H2/C2H4[J]. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces,2017,9(34): 29374-29379.

[22]. Yang S, Ramirez-Cuesta A J, Newby R, et al. Supramolecular binding and separation of hydrocarbons within a functionalized porous metal-organic framework[J] Nature Chemistry, 2014, 7(2): 121-129.

[23]. Cui X, Chen K, Xing H, et al. Pore chemistry and size control in hybrid porous materials for acetylene capture from ethylene[J]. Science, 2016, 353(6295): 141-144.

[24]. Sun Hongwei, Zhang Guojun. Significant breakthroughs by Chinese chemical researchers in the separation of acetylene and ethylene [J]. China Science Foundation, 2016, 30(4): 384.

[25]. Li B, Cui X, O'nolan D, et al. An ideal molecular sieve for acetylene removal from ethylene with record selectivity and productivity[J]. Advanced Materials, 2017, 29(47): 1704210.

[26]. Lin R-B, Li L, Zhou H-L, et al. Molecular sieving of ethylene from ethane using a rigid meta-organic framework[J]. Nature Materials, 2018, 17(12): 1128-1133.

[27]. Li L, Lin R-B, Krishna R, et al. Ethane/ethylene separation in a metal-organic framework with iron-peroxo sites[J].Science, 2018,362(6413): 443-446.

[28]. Cadiau A, Adil K, Bhatt P M, et al. A metal-organic framework-based splitter for separating propylene from propane[J]. Science,2016,353(6295): 137-140.

[29]. Grande C A, Gascon J, Kapteijn F, et al. Propane/propylene separation with Li-exchanged zeolite 13X[J]. Chemical Engineering Journal,2010,160(1): 207-214.

[30]. Grande C A, Rodrigues A E. Propane/propylene separation by pressure swing adsorption using Zeolite 4A[J]. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research,2005, 44(23): 8815-8829.

[31]. Liao Y, Zhang L, Weston M H, et al. Tuning ethylene gas adsorption via metal node modulation: Cu-MOF-74 for a high ethylene deliverable capacity[J]. Chemical Communications,2017,53(67):9376-9379.

[32]. Bloch E D, Queen W L, Krishna R, et al. Hydrocarbon separations in a metal-organic framework with open iron(II) coordination sites[J]. Science, 2012, 335(6076): 1606-1610.

[33]. Yang H, Peng F, Dang C, et al. Ligand charge separation to build highly stable Quasi-Isomer of MOF-74-Zn[J].Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2019,141(25): 9808-9812.

[34]. Wang H, Dong X, Colombo V, et al. Tailor-made microporous metal-organic frameworks for the full separation of propane from propylene through selective size exclusion[J]. Advanced Materials,2018,30(49): 1805088.

Cite this article

Xu,B. (2024). Gas adsorption and separation applications of MOF materials. Applied and Computational Engineering,89,184-193.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Functional Materials and Civil Engineering

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Yu J, Xie L-H, Li J-R, et al.CO2 capture and separations using MOFs: Computational and experimental studies[J]. Chemical Reviews2017117(14): 9674-9754.

[2]. Spanopoulos I, Tsangarakis C, Klontzas E, et al. Reticular synthesis of HKUST-like to-MOFs with enhanced CH4 storage[J]. Journal of the American Chemical Society,2016,138(5): 1568-1574.

[3]. Chen Dandan, Chen Deli, Xu Chunhui, et al. Research progress on the impact of water vapor on the adsorption and separation of mixed gases by MOFs materials [J]. Guangdong Chemical Industry 2017, 44(8): 94-95+126.

[4]. Eddaoudi M, Kim J, Rosi N, et al. Systematic design of pore size and functionality in isoreticular MOFs and their application in methane storage[J]. Science, 2002, 295(5554):469-472.

[5]. Grant Glover T, Peterson G W, Schindler B J, et al. MOF-74 building unit has a direct impact on toxic gas adsorption[J]. Chemical Engineering Science, 2011, 66(2): 163-170.

[6]. Zhang Z, Yao Z-Z, Xiang S, et al. Perspective of microporous metal-organic frameworks for CO2 capture and separation[J]. Energy & Environmental Science, 2014, 7(9): 2868-2899.

[7]. Jiang J, Lu Z, Zhang M, et al. Higher symmetry multinuclear clusters of metal-organic frameworks for highly selective CO capture[J]. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2018,140(51): 17825-17829.

[8]. Jiang Y Tan P, Qi S-C, et al. Metal-organic frameworks with target-specific active sites switched by photoresponsive motifs: Efficient adsorbents for tailorable CO2 capture[J]. Angewandte Chemie International Edition,2019,58(20): 6600-6604.

[9]. Nugent P, Belmabkhout Y, Burd S D, et al. Porous materials with optimal adsorption thermodynamics and kinetics for CO2 separation[J]. Nature, 2013,495: 80-84.

[10]. Nugent P, Belmabkhout Y, Burd S D, et al. Porous materials with optimal adsorption thermodynamics and kinetics for CO2 separation[J]. Nature, 2013, 495: 80-84.

[11]. O’nolan D, Kumar A, Zaworotko M J.Water vapor sorption in hybrid pillared square grid materials[J].Journal of the American Chemical Society2017139(25): 8508-8513

[12]. Chen K-J, Madden D G, Pham T, et al. Tuning pore size in square-lattice coordination networks for size-selective sieving of CO2[J]. Angewandte Chemie International Edition.2016,55(35): 10268-10272.

[13]. [13] Liao P-O, Chen X-W, Liu S-Y, et al. Putting an ultrahigh concentration of amine groups into a metal-organic framework for CO2 capture at low pressures[J]. Chemical Science, 2016.7(10):6528-6533.

[14]. Siegelman R L, Mcdonald T M, Gonzalez M I, et al. Controlling cooperative CO2 adsorption in diamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) metal-organic frameworks[J]. Journal of the American Chemical Society,2017,139(30): 10526-10538.

[15]. Mcdonald T M, Mason J A, Kong X, et al. Cooperative insertion of CO2 in diamine-appended metal-organic frameworks[J]. Nature, 2015,519(7543): 303-308.

[16]. PENG Y, KRUNGLEVICIUTE V, ERYAZICI I, et al. Methane storage in metal–organic frameworks: current records, surprise findings, and challenges [J]. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2013, 135(32): 11887-11894.

[17]. CHEN Z, LI P, ANDERSON R, et al. Balancing volumetric and gravimetric uptake in highly porous materials for clean energy [J]. Science, 2020, 368(6488): 297-303.

[18]. YUAN Y, WU H, XU Y, et al. Selective extraction of methane from C1/C 2/C 3 on moisture-resistant MIL-142A with interpenetrated networks [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2020, 395: 125057.

[19]. TU S, YU L, LIN D, et al. Robust nickel-based metal–organic framework for highly efficient methane purification and capture [J]. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2022, 14(3): 4242-4250.

[20]. Fan C B, Le Gong L, Huang L, et al. Significant enhancement of C2H2/C2H4 separation by a photochromic diarylethene unit: A temperature- and light-responsive deparation switch[J]. Angewandte Chemie International Edition,2017,56(27): 7900-7906.

[21]. Hong X-J, Wei Q, Cai Y-P, et al. Pillar-layered metal-organic framework with sieving effect and pore space partition for effective separation of mixed gas C2H2/C2H4[J]. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces,2017,9(34): 29374-29379.

[22]. Yang S, Ramirez-Cuesta A J, Newby R, et al. Supramolecular binding and separation of hydrocarbons within a functionalized porous metal-organic framework[J] Nature Chemistry, 2014, 7(2): 121-129.

[23]. Cui X, Chen K, Xing H, et al. Pore chemistry and size control in hybrid porous materials for acetylene capture from ethylene[J]. Science, 2016, 353(6295): 141-144.

[24]. Sun Hongwei, Zhang Guojun. Significant breakthroughs by Chinese chemical researchers in the separation of acetylene and ethylene [J]. China Science Foundation, 2016, 30(4): 384.

[25]. Li B, Cui X, O'nolan D, et al. An ideal molecular sieve for acetylene removal from ethylene with record selectivity and productivity[J]. Advanced Materials, 2017, 29(47): 1704210.

[26]. Lin R-B, Li L, Zhou H-L, et al. Molecular sieving of ethylene from ethane using a rigid meta-organic framework[J]. Nature Materials, 2018, 17(12): 1128-1133.

[27]. Li L, Lin R-B, Krishna R, et al. Ethane/ethylene separation in a metal-organic framework with iron-peroxo sites[J].Science, 2018,362(6413): 443-446.

[28]. Cadiau A, Adil K, Bhatt P M, et al. A metal-organic framework-based splitter for separating propylene from propane[J]. Science,2016,353(6295): 137-140.

[29]. Grande C A, Gascon J, Kapteijn F, et al. Propane/propylene separation with Li-exchanged zeolite 13X[J]. Chemical Engineering Journal,2010,160(1): 207-214.

[30]. Grande C A, Rodrigues A E. Propane/propylene separation by pressure swing adsorption using Zeolite 4A[J]. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research,2005, 44(23): 8815-8829.

[31]. Liao Y, Zhang L, Weston M H, et al. Tuning ethylene gas adsorption via metal node modulation: Cu-MOF-74 for a high ethylene deliverable capacity[J]. Chemical Communications,2017,53(67):9376-9379.

[32]. Bloch E D, Queen W L, Krishna R, et al. Hydrocarbon separations in a metal-organic framework with open iron(II) coordination sites[J]. Science, 2012, 335(6076): 1606-1610.

[33]. Yang H, Peng F, Dang C, et al. Ligand charge separation to build highly stable Quasi-Isomer of MOF-74-Zn[J].Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2019,141(25): 9808-9812.

[34]. Wang H, Dong X, Colombo V, et al. Tailor-made microporous metal-organic frameworks for the full separation of propane from propylene through selective size exclusion[J]. Advanced Materials,2018,30(49): 1805088.