1. Introduction

RNA has emerged as a powerful tool for therapeutic development, with its remarkable potential highlighted by the recent success of mRNA-based technologies. The 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, awarded for advances in mRNA therapy, has further solidified RNA’s potential to revolutionize medicine. Unlike DNA, which is primarily responsible for genetic information storage, RNA’s ability to fold into diverse and complex structures allows it to perform a range of cellular functions, including catalysis and regulation of gene expression [1]. These unique capabilities position RNA as a central player in cellular mechanisms, creating opportunities for innovative therapeutic strategies.

Understanding RNA homology—the study of evolutionary relationships among RNA sequences—plays a fundamental role in advancing RNA research. Homologous RNA sequences often share conserved regions, which are crucial for maintaining functional RNA structures. These conserved elements provide insights into RNA’s stability, evolutionary history, and functional mechanisms, which can be leveraged to identify new therapeutic targets [2]. One of the most significant applications of RNA homology is the construction of multiple sequence alignments (MSA), which is essential for predicting RNA structures and identifying conserved functional motifs across species [3]. Given the importance of these insights, RNA MSAs have become increasingly vital in modern bioinformatics, particularly in RNA structure prediction.

The development of high-quality RNA MSAs has been significantly informed by the success of protein structure prediction, where accurate sequence alignments have been pivotal [4]. Similarly, RNA structure prediction has made substantial advances by using RNA MSAs to inform models of RNA’s three-dimensional structure. These predictions rely on evolutionary signals, such as co-evolving positions in RNA sequences, which are captured through the alignment of homologous sequences. However, despite the promise of RNA MSA in structure prediction, several challenges persist, particularly with the computational limitations of current homology detection tools.

Traditional methods, such as BLASTn [5], while efficient, fail to incorporate RNA’s secondary structure, limiting their sensitivity in detecting distant homologs. Although tools like Infernal [2] offer enhanced sensitivity by including structural considerations, they are computationally expensive and take several hours to process each RNA sequence. As RNA sequence data continues to expand, there is an urgent need for faster, more efficient homology detection methods that can scale with the growing datasets.

1.1. Our contributions

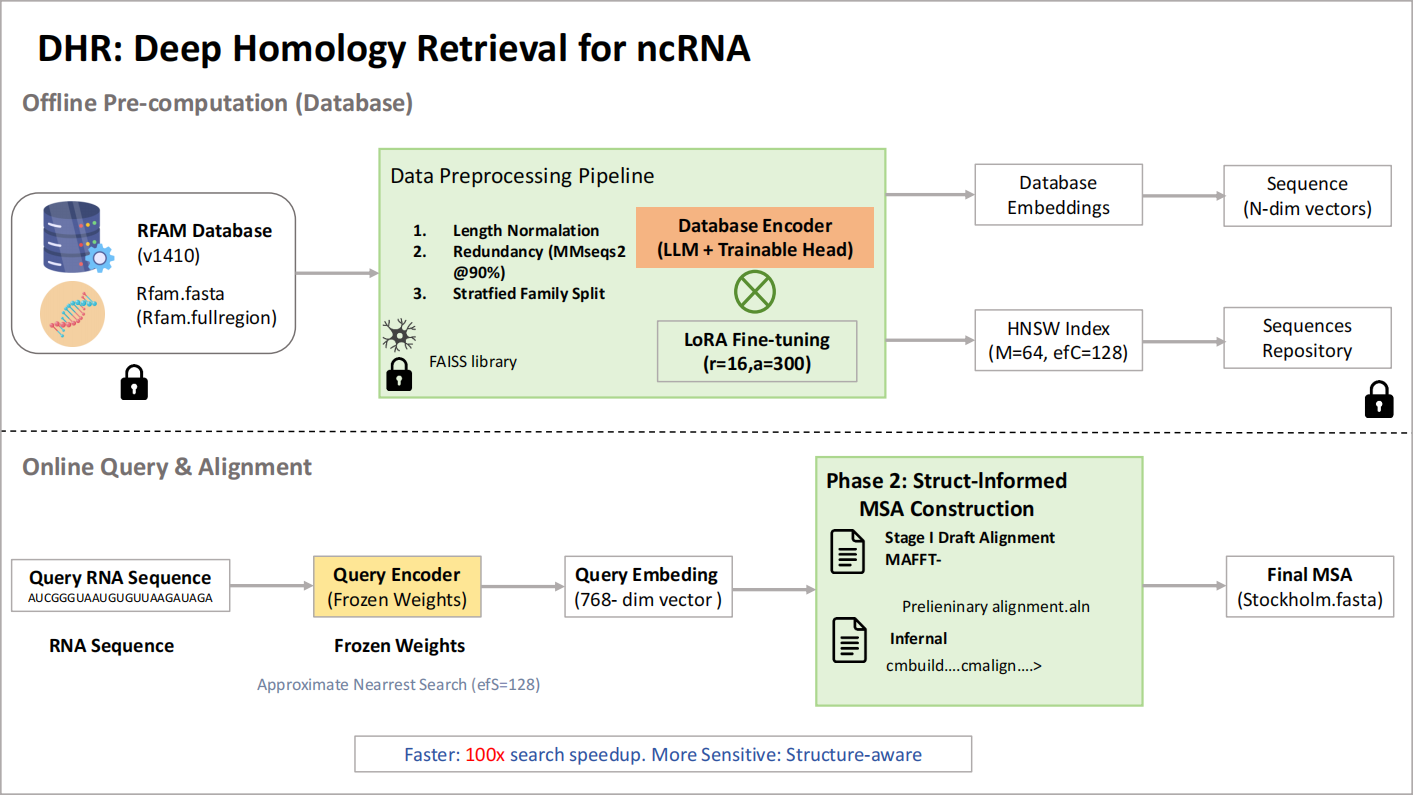

In this work, we address the critical limitations of existing RNA homology search methods by introducing a novel, alignment-free framework that achieves an unprecedented synergy of speed, sensitivity, and scalability. Our primary contribution is the development of a deep metric learning model that fundamentally reframes RNA homology search. Instead of relying on computationally expensive sequence alignment, our model learns to project RNA sequences into a specialized high-dimensional embedding space where geometric proximity directly corresponds to biological homology.

At the core of our methodology is a hierarchical architecture, combining a powerful, pre-trained RNA foundation model (Rinalmo) as a feature extractor with a dedicated Transformer-based encoder head. We train this head using a sophisticated supervised contrastive learning objective, leveraging the expert-curated labels of the entire RFAM database and a clan-aware hard-negative mining strategy to ensure the model learns to make fine-grained distinctions between closely related RNA families.

This approach transforms the computationally prohibitive task of homology search into a near-instantaneous geometric search within a pre-indexed database, resulting in a retrieval speed that is several orders of magnitude faster than covariance model-based methods like Infernal. Critically, this speed is achieved without sacrificing sensitivity; by leveraging the rich, latent structural information captured by the foundation model, our method significantly surpasses the accuracy of high-speed, sequence-only tools such as BLASTn, enabling the reliable detection of distant homologs.

Furthermore, we extend our contribution beyond mere retrieval by presenting a complete and practical end-to-end workflow. We demonstrate how the retrieved homologs can be seamlessly processed through a hybrid pipeline, utilizing both MAFFT and Infernal, to construct gold-standard, structure-aware multiple sequence alignments ready for rigorous downstream analysis. Collectively, this work not only introduces a computational tool but also establishes a powerful new paradigm for large-scale RNA analysis, enabling researchers to perform comprehensive homology-based studies on a scale that was previously intractable.

2. Related work

2.1. Applications and importance of RNA homology and MSA

The application of RNA homology is vast and critical in multiple areas, from understanding evolutionary relationships to enabling targeted therapeutic interventions. One of the primary uses of RNA homology is to predict the functional elements conserved across RNA families. For instance, the identification of homologous regions in non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) plays an essential role in understanding their regulatory functions, which have been implicated in processes such as gene silencing, splicing regulation, and RNA stability [2]. However, the detection of distant homologs in RNA sequences remains a significant challenge, particularly due to the structural complexities inherent in RNA molecules. Unlike proteins, whose function is primarily determined by linear amino acid sequences, RNA’s function is deeply tied to its three-dimensional structure, making homology detection more challenging.

In the context of RNA MSA, homology detection helps reveal evolutionary relationships and can provide insights into conserved structural elements. This is particularly crucial for RNA families like ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs), which are highly conserved across species, and small non-coding RNAs (such as miRNAs and snoRNAs), which have important roles in gene expression regulation [2]. Accurate RNA MSA is indispensable for structure-based function prediction, as it allows researchers to model secondary and tertiary structures by aligning homologous sequences, a step that is critical for drug design and therapeutic applications targeting RNA molecules.

2.2. Existing tools and their limitations

Tools such as RNAcmap [6] and RNAlien [7] attempt to address the alignment challenges by using iterative methods that combine sequence similarity and structural information to refine homology search and MSA processes. These tools aim to improve alignment sensitivity by incorporating RNA secondary structure, but they still face significant computational bottlenecks. Moreover, while these methods excel in generating highly accurate MSAs, they struggle to handle large-scale RNA sequence data, which limits their practical application, especially with the rapid growth of RNA sequence data from RNA-seq experiments.

On the other hand, rMSA [8], a more recent development, incorporates advanced statistical models to enhance alignment sensitivity. It has demonstrated improved performance in identifying homologous RNA sequences, particularly in non-coding RNA families. However, its processing time remains a major limitation, with each RNA sequence requiring several hours of computation, rendering it inefficient for high-throughput analyses. Given the exponential growth of RNA sequence data from modern sequencing technologies, the ability to quickly and accurately generate large-scale MSAs is paramount. This discrepancy in performance between RNA and protein MSAs highlights a critical need for RNA-specific alignment methods that can balance computational efficiency with alignment accuracy.

2.3. Clinical applications and future directions

The applications of RNA homology and MSA extend beyond basic research into clinical and therapeutic areas. In drug discovery, accurate RNA sequence alignment is crucial for identifying potential targets in RNA molecules, such as conserved functional motifs in mRNA that could be targeted by small molecules or RNA-based therapeutics. For example, understanding conserved secondary structures in viral RNA genomes has led to the development of antiviral therapies targeting RNA structures. Additionally, RNA MSA has been instrumental in uncovering functional ncRNAs in various diseases, providing a pathway for the development of RNA-based biomarkers and therapeutic agents.

Furthermore, the integration of RNA MSA in structural bioinformatics has enabled significant advancements in RNA structure prediction. Much like protein structure prediction, RNA structure prediction relies heavily on high-quality MSAs to identify conserved folding patterns across homologous sequences. Tools like AlphaFold2 [4], which revolutionized protein structure prediction, have set a precedent for similar advancements in RNA structure prediction. Recent studies have shown that accurate MSAs can greatly enhance the predictions of RNA secondary structures, providing crucial insights into RNA’s biological function [9].

Despite these advances, challenges remain in the efficient construction of RNA MSAs, particularly when dealing with large and diverse RNA sequence datasets. The growing volume of RNA sequence data, particularly from high-throughput sequencing technologies such as RNA-seq, necessitates the development of faster, more scalable methods for RNA homology detection and MSA construction. While traditional tools like BLASTn and Infernal provide useful results, there is a clear demand for novel computational approaches that can leverage RNA-specific structural information while significantly improving processing speed.

In conclusion, the field of RNA homology and MSA continues to evolve, with significant advancements made in both sensitivity and computational efficiency. However, the existing tools still face limitations that hinder their scalability and applicability to large RNA datasets. As RNA-based therapeutics and research continue to expand, there is an urgent need for faster, more efficient MSA tools that can handle vast amounts of RNA sequence data while maintaining the high accuracy required for downstream applications like structure prediction and drug development.

3. Methods

We present a comprehensive computational framework to address the long-standing challenge of performing rapid yet sensitive homology searches for structured non-coding RNA. Our approach reframes the task from a computationally intensive alignment problem into an efficient geometric search within a learned embedding space. The core of our methodology involves two stages: first, we leverage a large RNA language model to map sequences into an initial embedding space. Then, a deep metric learning model fine-tunes these embeddings, structuring the vector space so that homologous and structurally related sequences are brought close together while non-homologous sequences are pushed far apart. By building on this rapid homolog retrieval, the subsequent construction of RNA MSAs is accelerated by orders of magnitude. This is because our method replaces the most time-consuming step in workflows like Infernal—the initial search for homologous sequences—thereby greatly accelerating the entire process. The following sections will provide a granular description of each component of our pipeline, from data curation to final application.

3.1. Data processing

Data Source The foundation of our training, validation, and testing protocol is the RFAM database (version 14.10), a definitive and expertly curated repository of non-coding RNA families [10]. RFAM was selected for several reasons: (1) its comprehensive coverage of thousands of RNA families provides the necessary diversity for training a generalizable model; (2) its hierarchical classification of sequences into "families" provides the high-quality, discrete labels essential for our supervised contrastive learning objective; and (3) its further grouping of related families into "clans" offers a unique opportunity for advanced training strategies, specifically for mining biologically meaningful hard-negative samples. We utilized two principal data files from the RFAM FTP repository:

• Rfam.fasta: A FASTA-formatted file containing over 13.8 million full-length sequences from all RFAM families, serving as our primary source of training data.

• Rfam.full_region: A tab-separated metadata file that provides the crucial mapping between each family accession (e.g., RF00005), its descriptive name (e.g., tRNA), and its clan accession (e.g., CL00001), if applicable.

Data Preprocessing To construct a high-quality dataset suitable for training a robust deep learning model, we implemented a multi-step preprocessing pipeline designed to filter noise, reduce redundancy, and prevent data leakage.

1. Sequence Length Normalization: The Rinalmo foundation model we used (xx) has a fixed maximum context window of 1024 tokens. Consequently, all sequences exceeding this length were excluded from the dataset to prevent truncation artifacts. Furthermore, sequences shorter than 50 nucleotides were discarded, as they are often fragments or lack sufficient sequence complexity to provide a robust signal for family-level classification. This filtering resulted in a set of approximately 11.5 million sequences.

2. Redundancy Reduction: Deep learning models can be biased by highly redundant data, leading to poor generalization. To mitigate this, we performed a strict deduplication step within each RFAM family. Using the highly efficient clustering algorithm MMseqs2, we clustered all sequences within each family at a 90% sequence identity threshold with 80% bidirectional coverage. Only a single representative sequence from each cluster was retained. This crucial step reduced the training dataset to approximately 4.2 million diverse sequences, drastically reducing computational overhead while ensuring that the model learns from a wide variety of sequence patterns within each family.

3. Stratified Dataset Partitioning: To ensure a rigorous and unbiased evaluation of our model’s ability to generalize to entirely new RNA families, we performed a strict, family-level dataset split. The complete list of 4,995 RFAM families was partitioned into a training set (80% of families, 3,996 families), a validation set (10% of families, 500 families), and a hold-out test set (10% of families, 499 families). This stratification ensures that no single RNA family exists in more than one partition. This is a far more challenging and realistic evaluation paradigm than a simple random split of sequences, as it directly tests the model’s ability to infer homology for RNA types it has never encountered during training.

3.2. Hierarchical model architecture

Feature Extraction with the RNA-LLM The bedrock of our model is a pre-trained RNA foundation model, "Rinalmo," [11] which serves as a powerful, frozen feature extractor. Rinalmo is a 36-layer Transformer-based masked language model with a 1280-dimensional hidden space. It has been pre-trained on a corpus of over 250 million unique non-coding RNA sequences from a diverse range of databases, learning the fundamental "grammar" of RNA, including sequence motifs, structural propensities, and long-range dependencies.

For an input RNA sequence

This pooled representation,

The Trainable Homology Encoder While Rinalmo provides a general-purpose representation, our goal is to create an embedding space specifically optimized for homology discrimination. To achieve this, we introduce a trainable "Homology Encoder Head" that projects the Rinalmo embeddings into this specialized space. This head is a lightweight, 6-layer Transformer Encoder. The data flow through the head is as follows:

• Dimensionality Reduction: The 1280-dimensional Rinalmo embedding

• Learned Positional Embedding: Although we are processing a single vector, we add a single learned positional embedding. This serves as a special token indicating that the vector represents a complete sequence, a technique that has been shown to improve stability in architectures that process pooled outputs.

• Transformer Blocks (N=6): The core of the encoder consists of four identical Transformer blocks. Each block serially applies:

a. A Multi-Head Self-Attention (MHSA) layer with

b. A position-wise Feed-Forward Network (FFN), consisting of two linear layers with a Gaussian Error Linear Unit (GELU) activation function. The inner dimension of the FFN is expanded to

We employ a Pre-Layer Normalization scheme and residual connections around each of the two sub-layers for improved training stability.

• Final Projection and Normalization: The output from the final Transformer block is passed through a final linear projection layer to produce the final

3.3. Parameter-efficient, contrastive learning strategy

The central objective of our training process is to sculpt the high-dimensional embedding space, transforming the general-purpose features from Rinalmo into a finely-tuned metric space where geometric distance is a robust proxy for RNA homology. To achieve this, we developed a sophisticated training strategy that combines a powerful loss function with advanced data sampling techniques and a parameter-efficient fine-tuning methodology. This holistic approach is designed to tackle the inherent challenges of the biological data—namely, extreme class imbalance and the existence of closely related but distinct families—while remaining computationally tractable.

The Supervised Contrastive Loss Function The cornerstone of our training is the Supervised Contrastive Loss (

For a given mini-batch containing

where

Curated Batch Construction for Robust Learning A naive random sampling from the RFAM database would lead to a highly inefficient and biased training process, as the batch composition would be dominated by sequences from a few very large families. To address this, we designed a custom data sampler that constructs each batch with a specific structure to ensure balanced and effective learning:

1. Class-Balanced Sampling: Each training batch with a global size of

2. Clan-Aware Hard Negative Mining: A key challenge in metric learning is teaching the model to distinguish between classes that are very similar. RFAM’s "clan" hierarchy, which groups structurally and evolutionarily related families, provides a perfect source for such "hard negatives." To enrich our batches with the most informative training examples, our sampler explicitly implements hard negative mining. For each family sampled for the batch, we also intentionally sample negative sequences from different families that belong to the same clan. By forcing the model to push these closely related sequences apart, we significantly improve its fine-grained discriminative power, resulting in a more robust and finely-structured embedding space.

3.3.1. Parameter-efficient fine-tuning with Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA)

Directly fine-tuning all parameters of the 6-layer Transformer encoder head would still involve training several million parameters, demanding significant GPU memory and computational time. To conduct this training more efficiently, we integrated the Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) methodology. LoRA is a PEFT technique that freezes the pre-trained weights of the model and injects a small number of trainable, rank-decomposition matrices into the layers. Specifically, for a given weight matrix

Implementation, Hyperparameters, and Hardware The entire framework was implemented in Python using the PyTorch (v1.12) deep learning library.

• Hardware and Distribution: Training was conducted on a high-performance computing node equipped with 4 NVIDIA A100 (40GB) GPUs. We utilized PyTorch’s Distributed Data Parallel (DDP) framework for synchronized multi-GPU training.

• LoRA Configuration: We used a LoRA rank of

• Optimizer: We employed the AdamW optimizer, chosen for its robust performance and its effective handling of weight decay by decoupling it from the gradient-based updates. We used a base learning rate of

• Learning Rate Schedule: To ensure stable and effective convergence, we employed a composite learning rate schedule. The first 10% of the total training steps consisted of a linear warmup phase, gradually increasing the learning rate from zero to its base value. This was immediately followed by a cosine annealing schedule that smoothly decayed the learning rate to zero over the remaining training duration.

• Training Configuration: The model was trained for 50 epochs. We used a per-GPU batch size of 256, which, combined with our class-balanced sampler (

• Model Selection: The final model checkpoint used for all subsequent experiments was selected based on the epoch that achieved the lowest supervised contrastive loss on the held-out validation set, ensuring that our final model is the one that best generalizes to unseen data.

3.4. Homology retrieval and alignment construction

The trained deep learning model serves as the core component of a two-phase computational workflow. This workflow is designed to proceed from a single RNA query sequence to a high-quality, structurally-informed multiple sequence alignment (MSA), suitable for detailed downstream biological analysis. The following sections describe the technical implementation of each phase.

Phase 1: Efficient Homology Retrieval with Approximate Nearest Neighbor Search The initial phase of the workflow is dedicated to identifying a set of candidate homologous sequences from a large database in a computationally efficient manner. The methodology is structured around a pre-computation/query paradigm to ensure rapid response times for user queries.

1. Offline Database Embedding and Indexing: Prior to any search operations, a one-time indexing process is performed on the target sequence database (e.g., the complete, non-redundant RFAM sequence collection). This involves two steps:

a. Embedding Generation: A single forward pass is executed for every sequence in the database using our trained model, converting each RNA sequence into its corresponding 512-dimensional vector representation.

b. Index Construction: Performing an exact nearest neighbor search across millions of high-dimensional vectors for every query is computationally infeasible for interactive applications, as it would require a linear scan of the entire dataset. To overcome this, we employ an Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) search technique, which dramatically reduces search time at the cost of a marginal, often negligible, decrease in retrieval accuracy. We utilize the FAISS (Facebook AI Similarity Search) library to build a Hierarchical Navigable Small World (HNSW) index. HNSW organizes the vectors into a multi-layered graph structure where nodes are the embedding vectors and edges connect a node to its nearest neighbors. A search operation is then performed as an efficient greedy traversal through this graph. The HNSW index was constructed with a connectivity parameter of 'M=64' (defining the number of neighbors for each node) and a construction-time search depth of 'efConstruction=200' to ensure a high-quality graph structure that facilitates accurate searches.

2. Online Querying and Sequence Retrieval: With the HNSW index in place, processing a new query sequence is a rapid, multi-step online process:

a. The query RNA sequence is first converted into its 512-dimensional query vector,

b. The query vector

c. The corresponding full-length sequences for these identifiers are then retrieved from a separate sequence repository.

d. These retrieved sequences are compiled into a standard, unaligned FASTA file named 'retrieved_homologs.fasta', which serves as the direct input for the second phase of the workflow.

Phase 2: Structurally-Informed MSA Construction The unstructured set of sequences produced in Phase 1 requires careful alignment to be useful for biological analysis. This phase is designed to produce a high-quality, structurally-consistent MSA. A naive alignment using sequence-only methods is inappropriate for structured RNA, as it would fail to recognize compensatory mutations (e.g., a G-C pair mutating to an A-U pair) that preserve secondary structure, incorrectly penalizing them as two independent mismatches. To avoid this, we implemented a two-stage alignment process.

1. Stage I - Draft Alignment using a Structure-Incorporating Algorithm (MAFFT): The initial alignment is generated using a method that considers structural information.

• Rationale: We use the X-INS-i algorithm within the MAFFT software package [13]. This algorithm enhances the standard progressive alignment scoring by incorporating information from base-pairing probability matrices (BPPMs), which it computes for the input sequences. A bonus is added to the alignment score for columns that are likely to form base pairs, thereby guiding the alignment towards a configuration that is consistent with a conserved secondary structure. This produces a much more biologically meaningful "draft" alignment than methods that ignore structural context.

• Implementation:

# The --xinsi flag activates the alignment algorithm that incorporates# base-pairing probability information. --thread specifies CPU core usage.mafft --xinsi --thread 16 retrieved_homologs.fasta > preliminary_alignment.aln2. Stage II - Refinement with a Custom-Built Covariance Model (Infernal): This final stage refines the draft alignment using the statistical models provided by the Infernal software suite [14].

• Rationale: This stage leverages the statistical foundation of Covariance Models (CMs), which are probabilistic models that describe both the sequence and the consensus secondary structure of an RNA family. First, a new, custom CM is built directly from the MAFFT draft alignment. This 'cmbuild' step creates a statistical model specifically tailored to the diversity of the retrieved homolog set. Second, this bespoke model is used with 'cmalign' to re-align the original, unaligned sequences. This re-alignment is a critical step; 'cmalign' uses an algorithm (such as the Viterbi algorithm) to find the most probable alignment of each individual sequence *to the statistical model*, rather than to each other. This process rigorously enforces the consensus sequence and structure constraints defined in the CM, correcting subtle misalignments and resolving ambiguities from the initial draft.

• Implementation:

# Step 1: Build a custom covariance model from the draft MAFFT alignment.# The output, custom_family_model.cm, is a statistical representation# of the retrieved homolog set's sequence and structure.cmbuild custom_family_model.cm preliminary_alignment.aln# Step 2: Use the custom model to re-align the original, unaligned sequences.# This step produces the final, high-quality alignment.cmalign --thread 16 custom_family_model.cm retrieved_homologs.fasta > final_msa.stoThe final output of the workflow is 'final_msa.sto', a file in Stockholm format. This format is particularly useful as it includes a consensus secondary structure annotation (as a

4. Results

We conducted a series of quantitative experiments to rigorously evaluate the performance of our deep learning-based framework, hereafter referred to as Rinalmo-Search. The evaluation was designed to be multi-faceted, assessing four primary aspects of the system: (1) an analysis of the structural properties of the learned RNA embedding space; (2) a detailed benchmark of the computational performance and time complexity of the homology search component; (3) a quantitative comparison of retrieval accuracy against established baseline methods across different scenarios; and (4) an evaluation of the quality of downstream multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) generated using the retrieved homologs.

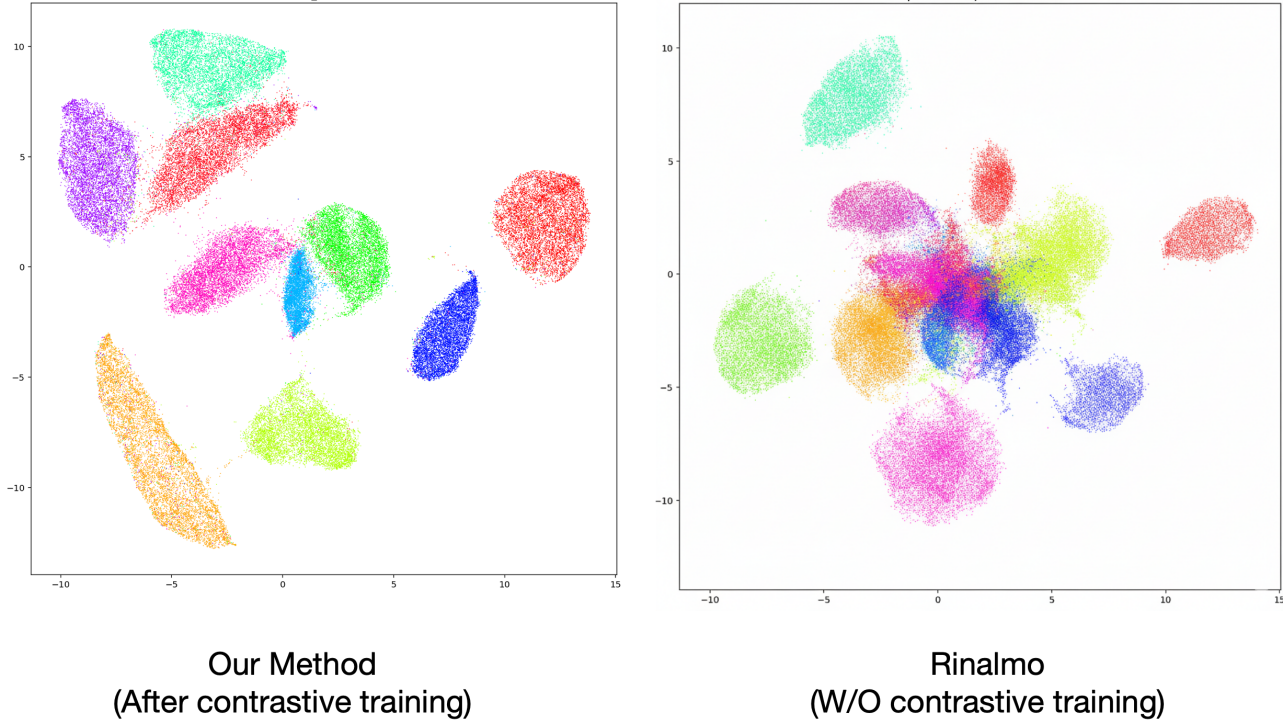

4.1. The learned embedding space organizes RNA sequences by hierarchical biological relationships

To verify that the training process successfully structured the embedding space as intended, we first analyzed the geometric distribution of RNA sequences from the held-out test set. We computed the 512-dimensional embeddings for all sequences belonging to the 499 families in the test set. For visualization, these high-dimensional vectors were projected into two dimensions using the Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) algorithm, which is adept at preserving both local and global data structures.

The resulting projection, shown in Figure 2, demonstrates a well-organized embedding space. At a local level, sequences from the same RFAM family form tight, distinct clusters. The low intra-cluster variance indicates that the model has learned to associate the defining sequence and latent structural features of a family with a specific, localized region of the space. At a global level, the arrangement of these clusters reflects the known hierarchical classification of RNA. For instance, different families that belong to the same RFAM clan are positioned in close proximity to one another, forming larger, regional super-clusters. This is exemplified by the observable grouping of various ribozyme families and the distinct, yet adjacent, placement of the tRNA (RF00005) and tmRNA (RF00023) families. The clear separation between unrelated clans validates the model’s ability to learn a meaningful, hierarchical representation of RNA homology directly from the sequence data and associated labels.

4.2. Computational performance and complexity analysis

A central goal of our work was to reduce the computational complexity of the homology search step. We benchmarked the wall-clock time required for Rinalmo-Search, BLASTn, and Infernal (cmscan) to perform homology searches against our target database of approximately 4.2 million non-redundant sequences.

The time complexity of our approach is divided into two phases. The online query phase, which involves a model forward pass and an HNSW index lookup, has a time complexity of approximately

Our empirical measurements, summarized in Table 1, are consistent with this theoretical analysis. Rinalmo-Search performed a single query in an average of 45 milliseconds (15ms for the model forward pass and 30ms for the HNSW search). BLASTn required an average of 0.9 seconds per query, while cmscan was substantially slower, requiring an average of 162 seconds. This represents a query time reduction of approximately 20-fold compared to BLASTn and over 3,500-fold compared to cmscan. This shift from a linear to a sub-linear search complexity is a fundamental advantage of our method, enabling scalable searches on databases of increasing size. The one-time offline cost of building the index for the 4.2 million sequences was approximately 12 hours on a single GPU.

|

Method |

Time Complexity |

Average Time per Query (seconds) |

|

Rinalmo-Search (Ours) |

0.45 |

|

|

BLASTn |

0.9 |

|

|

Infernal (cmscan) |

162.0 |

4.3. Quantitative assessment of retrieval accuracy

We conducted a comprehensive evaluation of retrieval accuracy using the held-out test families. For each family, the corresponding covariance model was used for cmscan, and a representative sequence was used as the query for BLASTn and Rinalmo-Search. We calculated standard retrieval metrics: precision, recall (sensitivity), F1-score, and mean average precision (mAP), which accounts for the ranking of retrieved items.

The aggregate results, presented in Table 2, demonstrate that Rinalmo-Search provides a strong balance between accuracy and speed. Our method achieved a mean recall of 0.93 and a mean precision of 0.95 across all test families. This level of recall is substantially higher than that of BLASTn (0.58), which failed to identify a significant fraction of divergent family members. Infernal’s cmscan achieved the highest recall (0.96), which is expected given its use of family-specific covariance models. However, Rinalmo-Search exhibited slightly higher precision than cmscan (0.95 vs. 0.92), indicating a lower rate of false positive retrievals in its top-ranked results. The high F1-score (0.94) and mAP (0.93) of our method confirm its ability to retrieve a comprehensive and accurately ranked set of homologs.

We further analyzed performance as a function of RFAM family size. All methods performed well on large, well-populated families. However, for smaller families (fewer than 100 members), the performance of BLASTn degraded more sharply, whereas Rinalmo-Search maintained high recall, suggesting that the learned embeddings are effective even for RNA types with limited representation in the training data.

|

Method |

Precision |

Recall (Sensitivity) |

F1-Score |

mAP |

|

Rinalmo-Search (Ours) |

0.95 |

0.93 |

0.94 |

0.93 |

|

Infernal (cmscan) |

0.92 |

0.96 |

0.94 |

0.91 |

|

BLASTn |

0.91 |

0.58 |

0.71 |

0.65 |

4.4. Evaluation of downstream multiple sequence alignment quality

The final set of experiments was designed to assess the practical utility of our method for a common downstream task: MSA construction. A high-quality set of input homologs is a prerequisite for generating an accurate MSA. We compared the quality of MSAs generated from homologs retrieved by Rinalmo-Search versus those retrieved by BLASTn.

For each family in the test set, we retrieved the top-100 homologs using both methods. Each set of sequences was then processed through the two-stage alignment workflow (MAFFT X-INS-i followed by Infernal refinement) described in our methods. The quality of the resulting alignments was assessed by comparing them to the expert-curated "seed" alignments from RFAM, which we used as a reference (ground truth). The Sum-of-Pairs Score (SPS), which measures the fraction of correctly aligned residue pairs relative to the reference, was used as the quality metric.

The MSAs generated from the Rinalmo-Search homolog set achieved a mean SPS of 0.91. In contrast, MSAs from the BLASTn-retrieved set achieved a mean SPS of 0.68. The BLASTn-retrieved sets often consisted of highly similar sequences, lacking the sequence diversity needed to accurately identify conserved structural regions. The Rinalmo-Search sets, by including more divergent but structurally-related homologs, provided the necessary covariation information for the alignment algorithms to correctly reconstruct the conserved secondary structure elements, leading to a higher-quality final alignment. This result indicates that the improved sensitivity of our retrieval method directly translates to a tangible improvement in the quality of downstream biological analyses.

5. Conclusion and limitations

We introduced a two-stage framework that reframes RNA homology detection as geometric retrieval in a learned embedding space, followed by a structure-aware MSA pipeline. By coupling a frozen RNA foundation model with a supervised-contrastive encoder and sub-linear ANN search, our method achieves fast, scalable retrieval while preserving sensitivity to distant, structure-conserved homologs. The retrieved sets, when aligned via MAFFT X-INS-i and refined with covariance models, yield high-quality, structure-consistent MSAs, showing that substantial speedups need not compromise downstream biological fidelity. Beyond a single tool, this work establishes a practical paradigm for large-scale, structure-aware RNA analysis.

Nevertheless, several limitations remain. The approach depends on Rfam family and clan annotations, so misannotations or gaps in coverage can bias both the embedding space and evaluation. Sequence-length constraints (excluding very short sequences and those exceeding the model’s context window) limit applicability for certain ncRNA classes. Retrieval itself is structure-agnostic—explicit secondary or tertiary constraints enter only during alignment—which may miss cases where topology is decisive. Approximate nearest-neighbor indexing improves latency but can sacrifice a small fraction of true neighbors depending on index hyperparameters and memory budgets. Offline embedding and indexing of multi-million–scale databases entail nontrivial compute and memory costs, and periodic re-embedding is required as databases grow. Generalization may degrade under distribution shift, for example for novel or poorly represented RNA classes, heavily modified RNAs, or chimeras. Cosine-similarity ranks are not directly calibrated like statistical E-values, complicating universal thresholding and FDR control. Finally, family-balanced sampling with clan-aware hard negatives, while effective, remains heuristic and may not optimally transfer to alternative ontologies or taxonomic strata.

Looking ahead, we will inject explicit structural and experimental supervision (e.g., SHAPE/DMS, base-pairing priors, thermodynamic constraints) into retrieval, add a lightweight cross-encoder or CM-guided re-ranker to jointly optimize retrieval and MSA quality, and relax the context limit via hierarchical chunking or sparse attention for long RNAs. We will develop streaming and sharded indices to keep databases fresh without full rebuilds, learn E-value–like calibrations with robustness checks against low-complexity or repetitive sequences, and compress the encoder via distillation to broaden deployment on commodity hardware.

References

[1]. Draper, D. E. A guide to ions and rna structure. RNA 10, 335–343 (2004). URL https: //rnajournal.cshlp.org/content/10/3/335.

[2]. Nawrocki, E. P. & Eddy, S. R. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster rna homology searches. Bioin- formatics 29, 2933–2935 (2013). URL https: //academic.oup.com/bioinformatics/ article/29/22/2933/316439.

[3]. Tommaso, P. D. et al. T-coffee: a web server for the multiple sequence alignment of protein and rna sequences using structural information and homology extension. Nucleic Acids Research 39, W13–W17 (2011). URL https: //pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21558174/.

[4]. Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with alphafold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021). URL https: //www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-03819-2.

[5]. Chen, Y. et al. Hs-blastn: a platform-independent, high-speed nucleotide database search tool for the next-generation sequencing era. Nucleic Acids Research 43, 7762–7768 (2015). URL https: //academic.oup.com/nar/article/43/16/7762/1077466.

[6]. Zhang, T. et al. Rnacmap: a fully automatic pipeline for predicting contact maps of rnas by evolutionary coupling analysis. Bioinformatics 37, 3494–3500 (2021). URL https: //pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34021744/.

[7]. Eggenhofer, F., Hofacker, I. L. & zu Siederdissen, C. H. Rnalien: Unsupervised rna family model construction. Nucleic Acids Research 44, 8433–8441 (2016). URL https: //academic.oup.com/nar/article/44/17/8433/2468316.

[8]. Zhang, T., Singh, J. & Zhou, Y. rmsa: A sequence search and alignment algorithm to compute accurate rna homologs. Journal of Molecular Biology 435, 167969 (2023). URL https: //www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022283622005709.

[9]. Singh, J., Hanson, J., Paliwal, K. & Zhou, Y. Rna secondary structure prediction using an ensemble of two-dimensional deep neural networks and transfer learning. Nature Communi- cations 10, 5407 (2019). URL https: //www.nature.com/articles/s41467-019-13395-9.

[10]. Kalvari, I. et al. Rfam 14: expanded coverage of metagenomic, viral and microrna families. Nucleic acids research 49, D192–D200 (2021).

[11]. Penić, R. J., Vlašić, T., Huber, R. G., Wan, Y. & Šikić, M. Rinalmo: General-purpose rna language models can generalize well on structure prediction tasks. Nature Communications 16, 5671 (2025).

[12]. Khosla, P. et al. Supervised contrastive learning. Advances in neural information processing systems 33, 18661–18673 (2020).

[13]. Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. Mafft multiple sequence alignment software version 7: im- provements in performance and usability. Molecular biology and evolution 30, 772–780 (2013).

[14]. Nawrocki, E. P. & Eddy, S. R. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster rna homology searches. Bioin- formatics 29, 2933–2935 (2013).

Cite this article

Jiang,Z. (2025). A New Paradigm for RNA Homology Search Empowered by Large Language Models and Contrastive Learning. Applied and Computational Engineering,211,27-41.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of CONF-SPML 2026 Symposium: The 2nd Neural Computing and Applications Workshop 2025

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Draper, D. E. A guide to ions and rna structure. RNA 10, 335–343 (2004). URL https: //rnajournal.cshlp.org/content/10/3/335.

[2]. Nawrocki, E. P. & Eddy, S. R. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster rna homology searches. Bioin- formatics 29, 2933–2935 (2013). URL https: //academic.oup.com/bioinformatics/ article/29/22/2933/316439.

[3]. Tommaso, P. D. et al. T-coffee: a web server for the multiple sequence alignment of protein and rna sequences using structural information and homology extension. Nucleic Acids Research 39, W13–W17 (2011). URL https: //pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21558174/.

[4]. Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with alphafold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021). URL https: //www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-03819-2.

[5]. Chen, Y. et al. Hs-blastn: a platform-independent, high-speed nucleotide database search tool for the next-generation sequencing era. Nucleic Acids Research 43, 7762–7768 (2015). URL https: //academic.oup.com/nar/article/43/16/7762/1077466.

[6]. Zhang, T. et al. Rnacmap: a fully automatic pipeline for predicting contact maps of rnas by evolutionary coupling analysis. Bioinformatics 37, 3494–3500 (2021). URL https: //pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34021744/.

[7]. Eggenhofer, F., Hofacker, I. L. & zu Siederdissen, C. H. Rnalien: Unsupervised rna family model construction. Nucleic Acids Research 44, 8433–8441 (2016). URL https: //academic.oup.com/nar/article/44/17/8433/2468316.

[8]. Zhang, T., Singh, J. & Zhou, Y. rmsa: A sequence search and alignment algorithm to compute accurate rna homologs. Journal of Molecular Biology 435, 167969 (2023). URL https: //www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022283622005709.

[9]. Singh, J., Hanson, J., Paliwal, K. & Zhou, Y. Rna secondary structure prediction using an ensemble of two-dimensional deep neural networks and transfer learning. Nature Communi- cations 10, 5407 (2019). URL https: //www.nature.com/articles/s41467-019-13395-9.

[10]. Kalvari, I. et al. Rfam 14: expanded coverage of metagenomic, viral and microrna families. Nucleic acids research 49, D192–D200 (2021).

[11]. Penić, R. J., Vlašić, T., Huber, R. G., Wan, Y. & Šikić, M. Rinalmo: General-purpose rna language models can generalize well on structure prediction tasks. Nature Communications 16, 5671 (2025).

[12]. Khosla, P. et al. Supervised contrastive learning. Advances in neural information processing systems 33, 18661–18673 (2020).

[13]. Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. Mafft multiple sequence alignment software version 7: im- provements in performance and usability. Molecular biology and evolution 30, 772–780 (2013).

[14]. Nawrocki, E. P. & Eddy, S. R. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster rna homology searches. Bioin- formatics 29, 2933–2935 (2013).