1. Introduction

The relationship between consumers and brands has evolved significantly, with an increased focus on the emotional and psychological aspects of their interaction [1]. It is no longer simply transactional, but influenced by a consumer's inherent desire to express their identity through their purchases [2], supporting McCracken’s [3] theory of meaning transfer. This theory suggests that cultural meanings flow from broader societal contexts to individual brands, and subsequently to consumers.

Despite substantial research on consumer-brand relationships treating brands as business partners or friends [1,4], new insights reveal that consumers consciously modify their behavior to enrich or sustain their self-concept [5]. This self-concept, defined as a consumer's perception of their own identity [6], can intertwine with a specific brand, leading to brand-self connections [7]. Brand-self connection is the extent to which consumers assimilate a brand into their self-concepts. In modern times, consumers seek more than a functional product from a brand. They desire an identity that resonates, a sense of belonging, and a compelling narrative [8]. This alignment between a brand and a consumer's self-concept is a significant driver of emotional consumer behavior [9].

This concept is particularly relevant in the luxury industry where purchasing decisions exceed basic utility and delve into the realm of self-expression and social status signaling [10]. Luxury consumers invest in the aspirational lifestyle and the higher social status that a brand promises, integrating their identity with that of the brand, thus cultivating a strong brand-self connection [11]. Furthermore, luxury consumers are often ready to pay a premium for intangible benefits such as prestige and exclusivity associated with a luxury brand [10].

Notably, while established research confirms that robust brand associations justify elevated prices [12], the direct correlation between brand-self connections and a consumer's willingness-to-pay (WTP) a premium is yet to be thoroughly examined. Our study aims at filling this research gap. We emphasize consumers’ WTP a price premium as a pivotal metric of brand value and a distinguishing competitive edge [8]. Subsequently, we propose a theoretical framework spotlighting consumers' brand experience and loyalty as conduits that articulate the influence of brand-self connections. Furthermore, in this digital era, social media engagement has become a crucial element of consumer-brand interaction [13] and could potentially moderate this relationship, offering a fresh perspective.

Our study brings several unique contributions to the fore:

For all we know, this is the inaugural study to concentrate on the value applicability of brand-self connection by associating it with consumers' WTP a price premium, which has the potential to drive enhanced profitability. This research deepens the understanding of the consumer-brand relationship and broadens the existing literature by revealing an potential consequences of brand-self connection.

Second, our research both theoretically outlines and empirically evaluates how brand experience and brand loyalty mediate the positive impact of brand-self connection on consumers’ WTP a premium. In doing so, we explore previously uncharted pathways through which brand-self connection influences consumers’ WTP a price premium.

Third, we highlight the strategic significance of brand-related social media engagement for luxury brands, which may greatly regulate luxury consumers’ WTP a price premium in the era of digital consumption.

Finally, studies have demonstrated differences in consumer perceptions across cultural environments [14], the Chinese luxury market presents a unique context since the unprecedented growth, driven by rising wealth and a growing middle class that aspires to express its newfound affluence through luxury consumption [15]. This study fills a gap by exploring brand-self connections and WTP a price premium in a non-Western context.

In the subsequent sections, we first establish the theoretical foundation and articulate our hypotheses. This is succeeded by the detailed research context and the methodology employed. Next, we delve into an exhaustive data analysis and discussion of results. Finally, we expound on the implications of our findings, acknowledge the limitations of the study, and propose avenues for the future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Brand-self connection and Willingness to pay a price premium

Rooted in the cornerstone of attachment theory, the concept of brand-self connection encapsulates a complex, evolving bond between an customer and a brand, akin to a shared history that requires cultivation over time [16]. This bond represents one facet of a broader concept known as brand attachment, delineated by the attachment-aversion model [17].

Essentially, the brand-self connection embodies the extent to which consumers incorporate a brand into their self-concept [18]. This integration is especially robust when personal experiences with the brand harmonize with the brand's image [19]. Parallelly, the self-verification theory sheds light on how self-congruity, a core element of brand-self connection, emerges and develops [20]. Research on brand-self connection often explores this intricate integration of brands into self-concept, taking into account the pivotal role of brand image in shaping consumer's self-congruity [18,21]. Evidence suggests that brand-self connections, whose intensity can vary with individual consumer attitudes towards the brand [19], are positively influenced by customer engagement and perceived brand quality [22]. These connections correlate significantly with customer advocacy [22], and carry a profound impact on consumers’ brand attitude, loyalty, word-of-mouth, and purchase intentions [2,23]. Furthermore, brand-self connection can elucidate the association between social media engagement and electronic word-of-mouth [24].

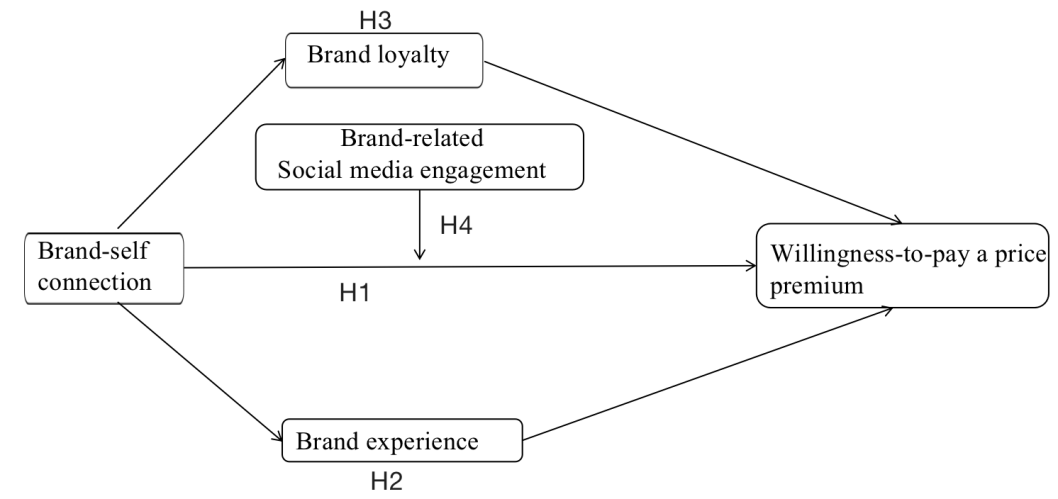

Based on previous research, we posit that a stronger brand-self connection may lead to a higher WTP a price premium. The conceptual model in our research is depicted in Figure 1. Brand attachment, conceptualized as an emotional bond with a specific brand [25], falls within a wider sphere of psychological commitments that are crucial to a consumer's allegiance to an entity [26]. These psychological commitments can predict future consumer behaviors, including the inclination to pay more money for a valued brand [27]. Also, research indeed shows that consumers agree to pay more for luxury brands that they are emotionally tied to, implying a positive correlation between brand attachment and the WTP a price premium [28,29].

A few empirical evidence from different industries echoes these findings. Studies show that consumers are prone to pay a higher price for luxury restaurant brands to which they have formed an attachment [28]. Moreover, when consumers foster an emotional bond with a brand or develop personal affection toward it, they are more inclined to pay a premium price [29,30]. Concurrently, the attachment-aversion model posits that brand-self connection forms one facet of brand attachment [17]. Therefore, we propose the first hypothesis:

H1: There is a positive association between brand-self connection and WTP among Chinese luxury consumers.

Figure 1: Conceptual Model [Owner-draw].

2.2. Brand Experience

As early as 1982, Holbrook et al. [31] indicated that consumer experiences are invoked when consumers engage with fantasies, feelings, and fun. This notion was expanded upon by Schmitt [32], who proposed that brand experiences transpire when consumers evaluate, purchase, or avail services. This conceptualization of brand experience was further refined by Brakus et al. [33], who suggested four dimensions to assess brand experience and predict consumer behavior: sensory, affective, intellectual, and behavioral. Verhoef et al. [34] proposed an all-encompassing model for the creation of customer experiences, incorporating five unique aspects: the social environment, the retail brand, the interface of the service, the dynamics of the customer experience, and strategies for managing customer experiences. Later, Lemon and Verhoef [35] provided further insight into brand experience across the customer journey, offering a historical perspective.

Existing research suggests that marketing activities and brand cues can enhance consumers' brand experience [36,37]. When considered as an independent variable, brand experience is shown to positively impact variables such as brand trust, brand loyalty, brand credibility, and brand attitude [33]. Notably, coupling cognitive brand experience with sensory and emotional brand experiences amplifies the brand's allure [38]. In addition, a positive brand experience can enhance customer satisfaction and stimulate word-of-mouth recommendations [39,40]. A rich brand experience can also shorten consumers' psychological distance to the brand, thus enhancing their understanding of it [41]. Empirical analysis by Yu et al. [42] further supports that brand experience positively mediates the effect between value co-creation and customer equity.

We propose that brand experience also serves as a mediator between brand-self connection and the WTP a price premium. Evidence suggests that as firms foster brand-self connections, consumers’ brand experiences are enriched [43]. Empirical research involving a sample of 317 respondents revealed that a stronger brand-self connection is associated with a more profound brand experience [2]. Earlier studies have also shown a significant influence of brand experience on WTP a price premium [44]. Brands that simplify the purchasing process and mitigate consumer concerns can command higher prices [12]. As consumers value enhancement of their experiential pleasure [45] and are less price-sensitive when seeking enjoyment through a brand [30], they are willing to pay more for a superior brand experience. This suggests that brand experience can explain the process between brand-self connection and WTP a price premium. Therefore, we put forth the following mediation hypothesis regarding brand experience:

H2: The relationship between brand-self connection and the willingness to pay a price premium among Chinese luxury consumers is mediated by brand experience.

2.3. Brand loyalty

Brand loyalty, as defined by Oliver in 1999 [46], encapsulates a consumer's persistent preference to repurchase a particular good or service in the future. Scholars typically agree that brand loyalty is a bi-dimensional concept, encapsulating both attitudes and behaviors [47]. Studies conducted by Assael [48] propose a positive linkage between customer loyalty and brand image, accomplished through behavioral and cognitive approaches to brand loyalty. Additionally, a study from Indonesia found that brand loyalty can mediate the effect between brand image and purchase intention of Apple products [49]. This study revealed that a favorable brand image is instrumental in encouraging repurchase. Meanwhile, enhancing brand loyalty can bolster purchase intentions.

Brand-self connection has been proved that can influence consumers’ post-purchase behavior [50]. What's more, post-purchase customer loyalty refers to the attachment to the products or services experienced by customers [46], which will lead to customers' post-purchase behavior, so they will simply purchase products repeatedly and this is the manifestation of brand loyalty [51]. Therefore, brand-self connection behavior will result to consumer’s brand loyalty [52]. In the hospitality sector, Tsai [53] revealed that guests who hold a strong affinity for a hotel brand and leverage this brand to express elements of their personal identity are more inclined to sustain their relationship with the hotel. The study further establishes that this sense of unity with the brand is instrumental in fostering brand loyalty. Therefore, a powerful brand-self connection tends to yield positive outcomes on brand loyalty.

In a survey of 362 buyers and sellers, Palmatier et al. [54] used triadic data to study the degree of loyalty among buyers, salespeople and companies. He found that both salespeople's loyalty and company loyalty increased customers' WTP and concluded that loyalty had a positive relationship with paying premium. In previous studies, schema theory was utilized to explain the impact of consumer satisfaction on their loyalty and premium payment [55, 56]. It was suggested that a positive experience of a product is more likely to make repeated purchases. In the consumer shopping experience, the perception that the service value equals or surpasses the price makes consumers more amenable to paying more, as postulated by Agarwal and Teas [57]. Further, Kahneman and Tversky [58] assert that heightened brand loyalty is often connected with heightened willingness among consumers to pay a premium. Customers who are loyal to a particular brand see a distinct value in that brand, making them less affected by changes in price. Consequently, they remain open to paying a higher price for a particular brand, even when faced with other alternatives [59]. We can conclude that brand loyalty also has a positive impact on the WTP premium. In combination with the main effect relationships mentioned in hypothesis 1 which is brand-self connection positively impact the WTP, we propose the third hypothesis:

H3: The relationship between brand-self connection and the willingness to pay a price premium is mediated by Chinese luxury consumers’ brand loyalty.

2.4. Brand-related social media engagement

The rapid growth and influence of social media have significantly transformed the dynamics of consumer-brand interactions. Taking it as an opportunity, companies adopt social media platforms like Twitter to build and maintain interactive relations with consumers [60] because these platforms allow consumers to engage more intimately and frequently with brands, facilitating stronger connections [61]. Social media engagement has been shown to deepen consumer relationships with brands, increase brand loyalty, and even influence purchase decisions [62,63]. Godey et al. [64] comprehensively measured the effect of social media engagement(SME) on fostering consumers’ WTP a premium price for specific luxury brand. Additionally, focusing on the Generation Y and Z consumers who actively engage in social media, Tafesse [61] found that consumers’ online brand engagement and brand love can influence their WTP a premium price towards target brands [61].

Besides that, brand-related social media engagement can particularly reinforce brand-self connections by providing consumers with a platform to express and reinforce their identities related to their preferred brands. For instance, when consumers share, comment, or like brand-related content, they are not only interacting with the brand but also integrating the brand into their online social identities [65]. Also, research has spotlighted the importance of social media engagement in Chinese consumers' purchase decisions [66]. As consumers engage with more brand-related content on social media, they not only interact with the brand but also observe and interact with others who associate with the brand, which can further strengthen their brand-self connection and enhance their perceived brand value, which can justify higher prices [63].

It can be theorized that consumers’ brand-related social media engagement may act as a moderating variable. Specifically, high levels of social media engagement may strengthen the impact of brand-self connections on the WTP a price premium. This is because active social media engagement could intensify brand-self connections, make them more salient to the consumer, and further encourage consumers to maintain congruence with their desired self-concept through their purchasing behaviors, such as paying a price premium for their preferred brands. Thus, we propose the fourth hypothesis:

H4: The relationship between brand-self connection and WTP a price premium is moderated by Chinese luxury consumers’ brand-related social media engagement.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research context, sampling, and data collection

The research setting focuses on a multi-dimensional survey of the Chinese consumer who were picked to answer luxury-brand-related questions. The luxury market in China has seen rapid growth, with projections estimating it to become the largest luxury goods market by 2025 [15]. This considerable growth presents a unique and valuable opportunity for academic exploration. The sampling strategy combined elements of snowball and convenience sampling to generate a large and diverse sample, providing insightful findings. In the aspect of data collection, our questionnaire survey initially garnered 312 responses. To ensure the robustness and accuracy of our data analysis, we embarked on a thorough data cleaning process after collecting data. This process involved removing responses that displayed random or inconsistent patterns, treating missing or incomplete entries, identifying and excluding statistical outliers, and deleting any duplicate submissions. The systematic cleaning process led to the exclusion of responses that could potentially compromise the reliability of our results, ultimately leaving us with 270 valid and high-quality responses. These remaining responses were deemed suitable and sufficient for further data analysis. The data collection effort obtained available responses in both male (38.7%) and female (61.3%). Regarding age distribution, 38.7% of the participants were between 18 and 24 years old, 27% fell into the 25 to 34 age bracket, 22.3% were between 35 and 44, while 12% were above 44 years. In terms of educational attainment, over half of the participants (58%) held a college degree, 17.3% had completed technical secondary school or junior college, 11.3% had a high school diploma, and the remaining 13.3% possessed a master's degree or higher. To evaluate the possible influence of non-response bias, we employed the method proposed by Armstrong and Overton [67]. This technique involves a comparison between the early respondents and those who responded later. Splitting our responses into two groups based on response timing—first and last quartile—we compared them across all study variables. The independent sample t-tests indicated that there was no significant differences between these two groups (p < 0.10), thus providing evidence that non-response bias is unlikely to significantly compromise our study's validity.

3.2. Survey instruments

The survey was administered online via Tencent's questionnaire platform to 300 respondents. To guide respondents in answering the subsequent questions based on a single luxury brand, we included a screening question asking, "What is your favorite brand?", supplemented with brand names (for example, Balenciaga, Chanel, Dior) to help respondents gain a better understanding. In order to gather accurate data for our study, we implemented five-point Likert scales which ranged from "strongly disagree" to "strongly agree". To evaluate the brand experience, we relied on scale from Brakus et al.'s [33] which takes into account different dimensions including the sensory, affective, behavioral, and intellectual aspects. Additionally, we determined the willingness-to-pay a price premium using Netemeyer et al.'s [68] three-item scale. During our research, we also utilized a seven-point Likert scale to assess various variables For example, the intensity of the brand-self connection was measured by a scale from Escalas and Bettman [7], and the double-barreled statement "I consider Brand X to be 'me'" was split into two distinct statements. Brand loyalty was assessed through Keller's [69] seven-item scale. Lastly, we gauged brand-related social media engagement through a seventeen-item Likert scale designed by Schivinski et al. [70], which focused on three essential dimensions: consumption, contribution and creation.

3.3. Common method bias

In our study, we were cognizant of the potential for common method bias, a recognized issue in survey research. Accordingly, we took preventative measures, adhering to the recommendations outlined by Podsakoff et al. [71] to mitigate this concern. We implemented strategies to mitigate this bias during the survey process. In addition, we performed ex post analyses to test for common method variance (CMV). Firstly, we conducted a principal component factor analysis, and the outcome demonstrated that the most significant explained variance before rotation was 36.74%, indicating no significant presence of CMV, as per Podsakoff and Organ [72]. Secondly, we executed a confirmatory factor analysis using only a single factor. The resulting model's fitness was inferior to the multi-factor models, further indicating that CMV isn't a major issue in our research. Hence, together, these analyses suggest that our research doesn't suffer from serious common method bias.

Table 1: Measures and CFA Results. [Owner-draw]

Measures and items | Loading | AVE | CR |

Brand Loyalty | 0.582 | 0.836 | |

I regard myself as loyal to this luxury brand. | 0.762 | ||

Given a choice, I always pick this luxury brand. | 0.738 | ||

I maximize my purchases from this luxury brand. | 0.721 | ||

I believe this is the sole luxury brand for this product I require. | 0.575 | ||

This luxury brand is my top choice to purchase/use. | 0.528 | ||

If this brand were unavailable, it would significantly impact me. | 0.626 | ||

I would take extra steps to ensure I use this luxury brand. | 0.578 | ||

Brand-self connection | 0.531 | 0.829 | |

This luxury brand mirrors who I am. | 0.742 | ||

I resonate with this high-end brand. | 0.678 | ||

There's a personal bond I feel with this luxury brand. | 0.658 | ||

This luxury brand serves as a medium to express my identity to others. | 0.750 | ||

I view this luxury brand as a representation of my self-perception. | 0.678 | ||

Brand Experience | 0.515 | 0.746 | |

[Brand] has a pronounced impact on my senses. | 0.616 | ||

[Brand] resonates with my sensory perception. | 0.599 | ||

[Brand] captivates my senses in a unique way. | 0.600 | ||

I possess deep feelings towards [Brand]. | 0.623 | ||

[Brand] evokes strong emotions. | 0.711 | ||

[Brand] evokes emotions and thoughts. | 0.752 | ||

[Brand] leads to bodily sensations. | 0.578 | ||

Physical reactions and emotions arise when I use [Brand]. | 0.603 | ||

[Brand] drives action. | 0.655 | ||

[Brand] piques my interest and challenges my problem-solving skills. | 0.636 | ||

Encountering [Brand] often prompts deep reflection. | 0.562 | ||

[Brand] makes me think. | 0.563 | ||

Brand-related social media engagement | 0.591 | 0.880 | |

I go through Brand X-related updates on social media. | 0.546 | ||

I browse through fan communities of Brand X on social platforms. | 0.621 | ||

I view images/illustrations associated with Brand X. | 0.525 | ||

I keep up with blogs discussing Brand X. | 0.663 | ||

I am a follower of Brand X on social platforms. | 0.523 | ||

I provide feedback on videos associated with Brand X. | 0.717 | ||

I remark on articles connected to Brand X. | 0.647 | ||

I comment on visuals/images linked to Brand X. | 0.677 | ||

I spread content associated with Brand X. | 0.816 | ||

I “Like” pictures/graphics related to Brand X. | 0.857 | ||

I “Like” posts related to Brand X. | 0.830 | ||

I start discussions about Brand X on blogging platforms. | 0.737 | ||

I kick off conversations about Brand X on social platforms. | 0.659 | ||

I share images/illustrations associated with Brand X. | 0.633 | ||

I upload videos featuring Brand X. | 0.810 | ||

I contribute to forum threads about Brand X. | 0.840 | ||

I write reviews related to Brand X. | 0.800 | ||

Willingness to pay a price premium | 0.710 | 0.957 | |

I am willing to spend more on this luxury brand compared to others. | 0.811 | ||

The cost of this luxury brand would need to rise substantially for me to consider a different brand. | 0.856 | ||

I am prepared to pay more on this luxury brand compared to others. | 0.861 |

Measurement model analysis: reliability and validity

We conducted a rigorous analysis of our scales' reliability and validity using SPSS 27.0. In evaluating the reliability of our measures, we computed Cronbach's alpha coefficient. The values ranged from αWillingness to pay a price premium= .821 to αBrand-related social media engagement = .976, signifying high reliability. Importantly, none of the alpha values changed significantly upon item deletion, underlining the internal consistency of the variables.

To further ensure the quality of our measurements, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis. We examined the all of the items’ standardized factor loading coefficients and computed the composite reliability and the average variance extracted for each variable to establish convergent validity. The results were very positive: as seen in Table 1, all standardized factor loading coefficients exceeded the benchmark of 0.5, all AVE values for each variable surpassed the 0.5 threshold, and every CR value for each variable exceeded 0.7 mark. These values, exceeding the commonly recommended thresholds in the literature [73], evidence good convergent validity. Hence, our measures demonstrate both internal consistency and good convergent validity, thereby solidifying the foundation of our nalysis. Table 2 provides descriptive statistics and correlations.

4. Testing hypothesis

Table 2: Descriptive statistics, square root of the AVE and correlations [Owner-draw]

Construct | Mean | SD | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

Brand-self Connection | 21.207 | 8.094 | 0.763* | ||||

WTP a price premium | 9.674 | 3.270 | 0.721 | 0.729* | |||

Brand Experience | 40.885 | 10.664 | 0.793 | 0.727 | 0.718* | ||

Brand Loyalty | 30.441 | 9.572 | 0.750 | 0.724 | 0.721 | 0.769* | |

Brand-related SME | 68.981 | 25.297 | 0.661 | 0.622 | 0.739 | 0.668 | 0.843* |

Notes: WTP a price premium= Willingness to pay a price premium; Brand-related SME = Brand-related social media engagement; *values in the main diagonal are the square root of the AVE; values below the diagonal are correlations. | |||||||

4.1. Main Effect

To discern the effect of brand-self connection on consumers’ WTP a price premium, we executed a regression analysis. The analysis yielded a significant and positive coefficient (b = 0.721, t = 17.019, p < 0.001), thereby substantiating Hypothesis 1. Furthermore, the model's R-squared value was 0.52, implying that brand-self connection accounts for 52% of the variance in consumers' WTP a premium price.

4.2. Mediation Effects

In accordance with the methodology suggested by Preacher and Hayes [74], we explored the mediating effects within our study. This exploration necessitated simultaneous estimation of both direct and indirect influences, achieved through a bootstrapping approach with 5000 resamples. Initially, we established a direct path from brand-self connection to consumers' WTP a price premium; a significant relationship would imply partial mediation through our proposed intermediaries. Subsequently, we investigated the overall indirect influence of brand-self connection on consumers' WTP a price premium. Our data analysis unveiled a substantial cumulative standardized indirect effect of 0.49 (p < 0.001; CI = 0.26 - 0.32), indicating a significant indirect impact of brand-self connection on consumers’ propensity to pay a price premium. We then turned our focus to investigating the distinct indirect effects exercised by each mediator, utilizing an amalytical approach known as phantom model analysis. Recognizing two separate indirect pathways from brand-self connection to consumers' WTP a premium, we implemented two corresponding phantom models. Using 5000 iterations, we generated 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals to further substantiate our analysis.

As shown in Table 3, the analysis showed a specific indirect effect of 0.13 (p = 0.001 < 0.05; 95% CI = 0.13–0.27) via brand experience, and 0.12 (p = 0.025 < 0.05; CI = 0.08–0.18) via brand loyalty. These results underscore the significance of both mediating pathways. Collectively, the findings suggest partial mediation by brand experience and brand loyalty, underscoring the notable indirect influence of brand-self connection on consumers’ WTP a price premium. Hence, both hypotheses H3 and H4 find support in our study.

Table 3: Mediation Effect Testing [Owner-draw]

Mediating Effect Testing | |||||

Pathway: Brand-self connection - Brand Experience - WTP a price premium | |||||

Dircet effect of BSC on WTPP | Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI | T-value |

0.157 | 0.026 | 0.105 | 0.208 | 5.986*** | |

Indirect effect of BSC on WTPP | Effect | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | |

0.135 | 0.027 | 0.086 | 0.191 | ||

Pathway: Brand-self connection - Brand loyalty - WTP a price premium | |||||

Dircet effect of BSC on WTPP | Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI | T-value |

0.164 | 0.024 | 0.118 | 0.211 | 6.916*** | |

Indirect effect of BSC on WTPP | Effect | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | |

0.127 | 0.024 | 0.798 | 0.176 | ||

Notes: BSC = Brand-self connection; WTPP = Willingness to pay a price premium ***p<0.001 | |||||

4.3. Moderation effect

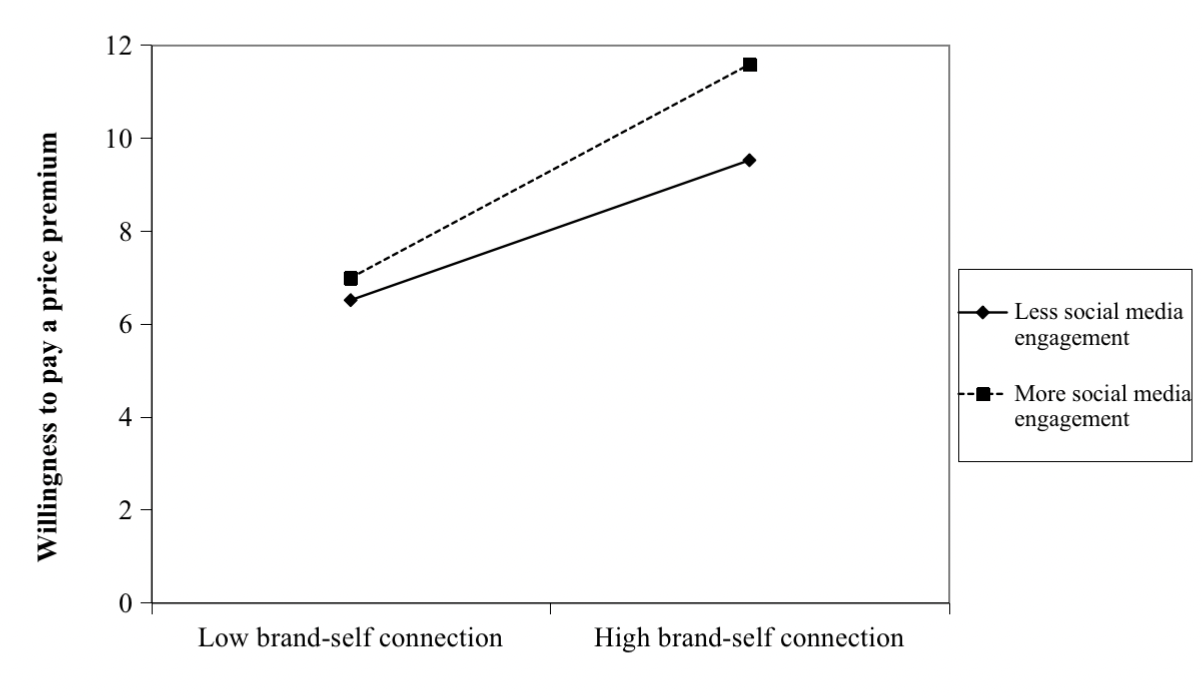

While evaluating the moderating effect of brand-related social media engagement on the link between brand-self connection and the WTP a price premium among Chinese luxury consumers, we utilized a moderation analysis via the PROCESS macro in SPSS. As shown in Table 4, the results showed a substantial positive interaction impact between brand-self connection and brand-related social media engagement on the WTP a premium (b = 0.0013, t = 2.22, p < 0.03). Specifically, this interaction effect suggested that the intensity and character of the relationship between the main effect changed in accordance with the degree of brand-related social media engagement. As a result, Hypothesis 4 is confirmed (See Figure 2).

Table 4: Moderating Effect Testing [Owner-draw]

Moderating Effect Testing | |||||

Outcome Variable: Willingness to Pay a Price Premium | |||||

Coeff. | se | t | LLCL | ULCL | |

Constant | 4.358 | 0.899 | 4.847*** | 2.587 | 6.127 |

Brand-self connection | 0.140 | 0.047 | 2.870** | 0.042 | 0.227 |

Brand-related social media engagement | 0.006 | 0.015 | 0.381 | -0.024 | 0.035 |

BSC x BRSME | 0.001 | 0.001 | 2.127* | 0.001 | 0.003 |

Notes: BSC = Brand-self connection; BRSME = Brand-related social media engagement | |||||

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 | |||||

Figure 2: Brand-related SME Moderating Effect on BSC – WTPP. [Owner-draw]

5. Conclusion

5.1. Interpretation of Findings

This research delved into the influence of brand-self connection on a consumer's WTP a price premium, specifically within the luxury market in China. The empirical findings offered strong support for our conjectures and broadened our comprehension of luxury consumer conduct. The pronounced positive impact of brand-self connection on consumers' WTP a price premium (H1) underscores the potent emotional bonds consumers form with brands. Moreover, brand experience and brand loyalty were revealed to partially mediate the influence of brand-self connection on the WTP a price premium (H2 and H3). This discovery suggests that an intense brand-self connection can enrich the brand experience and foster consumer loyalty, indirectly compelling consumers to pay a premium price.

Our study also revealed the moderating role of brand-related social media engagement in the main effect (H4). However, the relatively small beta coefficient value (b = 0.0013) suggests that the moderating effect is not particularly substantial. This finding indicates that while brand-related social media engagement does exert some influence on the relationship between these two variables, the extent of this influence remains somewhat muted.

This minor moderating effect can be contextualized by referring to previous research. Existing studies reveal that the experience consumers glean from social media interaction with brands doesn't significantly differ across diverse brands, as the functionality of these platforms remains largely uniform across industries and markets [75]. Hence, a consumer's engagement with a luxury brand like Prada on social media might not be markedly distinct from their engagement with Starbucks or any other non-luxury brand. This lack of unique brand experience on social media platforms might potentially mitigate the impact of brand-related social media engagement. Moreover, in physical stores, the tailored service and the sensory experience play a crucial role in forging a deeper connection between consumers and luxury brands, thereby potentially augmenting their willingness to pay a premium. Given the current limitations of social media in delivering these unique, personalized experiences sought by luxury consumers, the moderating effect of brand-related social media engagement might not be significantly robust in the luxury market.

5.2. Theoretical implication

Our research provides several noteworthy contributions to scholarly literature. Firstly, it delves into uncharted territory by investigating the association between brand-self connection and the willingness to pay a premium price within the context of China's luxury market. By confirming a tangible link between brand-self connection and the financial advantages accrued from premium pricing, our study extends the existing literature on brand-self connections and pricing strategy. This fresh perspective sparks new avenues for future research, encouraging a more comprehensive exploration of the influence of consumers' self-identification with a brand on their purchasing decisions.

Secondly, our research emphasizes the significant role of brand loyalty and brand experience in brand management, reinforcing ideas supported by previous studies [33,55]. We enhance these theories by disclosing the mediating influences of brand experience and brand loyalty on the relationship between brand-self connection and WTP a premium. This suggests that consumers' brand-self connection extends beyond individual brand interaction, and is shaped by their broader brand experience and loyalty to the brand. This refined understanding augments the existing literature and sets the stage for future investigations into the complex dynamics of consumer-brand relationships in luxury markets. It also paves the way for further exploration of how consumer-brand relationships translate into financial outcomes.

Lastly, our research substantially bridges a prevailing gap in the current academic landscape regarding the role of social media engagement in luxury brand management and consumer behavior. Previous studies have emphasized the potential of social media in constructing a brand image, but the effect of social media engagement in altering the relationship between brand-self connection and WTP a premium has largely remained uncharted territory. In addition to this, our study carves out a new niche in the existing knowledge base by revealing a minor moderating effect of brand-related social media engagement. This suggests that the influence of social media engagement might become somewhat diluted in the luxury market, thus offering a more nuanced view of the role social media plays in shaping the behaviors of luxury consumers.

5.3. Managerial implication

From an managerial viewpoint, these results offer valuable guidance for brand managers and marketers within the luxury industry. Given our observations, it's critical for luxury brands in the Chinese market to focus on bolstering brand-self connections as a means of enhancing consumers' readiness to pay a higher price. To ensure this, an in-depth and comprehensive comprehension of the target customer base is crucial, achievable via thorough market research that encapsulates consumer persona, their values, aspirations, and lifestyle nuances. The gleaned insights should subsequently be reflected in the brand's storytelling, product development, and marketing strategies, thereby positioning the brand as an integral facet of their customers' self-expression and identity.

Further, the importance of enriching the brand experience should not be overlooked. Providing exceptional in-store and online experiences that transcend the transactional purchase, like exclusive events, personalized services, product customization, and access to limited-edition collections, will not only provide an avenue for consumers to interact with the brand, but also set the brand apart from its competitors. Investing in robust loyalty programs rewarding repeat purchases and brand advocacy, for instance, tiered loyalty programs offering exclusive perks and benefits to loyal customers, will simultaneously foster brand loyalty and increase consumers' WTP a price premium.

Even with its smaller moderating role, social media engagement is still crucial for luxury brands. They should strive to differentiate their brand experiences on these platforms by fostering a sense of community, engaging consumers with exclusive, brand-centric content that offers an insider look into the brand's world, such as behind-the-scenes videos, designer interviews, and live-streamed fashion shows. To mimic the premium in-store service, luxury brands could also offer personalized online customer service.

Finally, given the luxury consumers' preference for personalized services, luxury brands should leverage data analytics and AI to create tailored digital experiences. This may involve personalized product recommendations, individualized social media content, and customized email marketing based on consumers' purchase history and browsing behavior. In conclusion, luxury brands need to conceptualize their strategy not just around selling products, but around selling an experience, a lifestyle, and an identity with which consumers can resonate. The deeper the brand integrates into consumers' lives, the greater their WTP a premium price, necessitating a holistic approach that encapsulates a compelling brand narrative, exceptional customer experiences and distinctive social media engagements.

5.4. Limitations and future direction

While this study provides insightful findings, there are a few limitations that should be recognized. These constraints, however, may pave the way for interesting opportunities in future research. Firstly, the cross-sectional design of our study provides a singular temporal snapshot, which hinders establishing causal relationships. Future studies employing longitudinal design could yield stronger empirical support for our theoretical framework by mapping the evolution of the relationships over time. Secondly, due to resource constraints, we utilized convenience and snowball sampling techniques. Although practical, these methods may introduce sampling bias and limit the results' generalizability. Future research could leverage diverse, representative sampling methods like stratified random or cluster sampling to enhance the findings' external validity and reliability. Thirdly, we focused on brand-self connection as the key driver of WTP a premium price, which was guided by the brand attachment perspective. However, the attachment-aversion model suggests a dual-dimensional approach to brand attachment, in which brand prominence is another aspect. Future research could explore other variables like brand prominence, to investigate additional factors influencing consumers' WTP a premium price. Fourthly, our findings are contextualized within the Chinese luxury market, which may limit their applicability to other contexts or industries. Future studies could extend our research by investigating similar relationships across different geographical regions and industries, thereby enhancing the generalizability and global relevance of our findings. Finally, the identified moderation suggests that our understanding of this process is tentative and calls for further research. This study can act as a springboard for future investigations that can provide a more definitive understanding of these dynamics.

References

[1]. Fournier, S. (1998) Consumers and their brands: Developing relationship theory in consumer research. Journal of consumer research, 24(4), pp.343-373.

[2]. van der Westhuizen, L.M. (2018) Brand loyalty: exploring self-brand connection and brand experience. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 27(2), pp.172-184.

[3]. McCracken, G. (1989) Who is the celebrity endorser? Cultural foundations of the endorsement process. Journal of consumer research, 16(3), pp.310-321.

[4]. Aggarwal, P. (2004) The effects of brand relationship norms on consumer attitudes and behavior. Journal of consumer research, 31(1), pp.87-101.

[5]. Grubb, E.L., Grathwohl, H.L. (1967) Consumer self-concept, symbolism and market behavior: A theoretical approach. Journal of marketing, 31(4), pp.22-27.

[6]. Rosenberg, M. (1989) Self-concept research: A historical overview. Social forces, 68(1), pp.34-44.

[7]. Escalas, J. E., Bettman, J. R. (2003) You are what they eat: The influence of reference groups on consumers' connections to brands. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 13(3), pp.339–348.

[8]. Aaker, J.L. (1997) Dimensions of brand personality. Journal of marketing research, 34(3), pp.347-356.

[9]. Ferraro, R., Escalas, J.E., Bettman, J.R. (2011) Our possessions, our selves: Domains of self-worth and the possession–self link. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 21(2), pp.169-177.

[10]. Vigneron, F., Johnson, L.W. (2004) Measuring perceptions of brand luxury. Journal of brand management, 11(6), pp.484-506.

[11]. Kapferer, J.N., Bastien, V. (2009) The specificity of luxury management: Turning marketing upside down. Journal of Brand management, 16(5-6), pp.311-322.

[12]. Dewar, N. (2004) What are brands good for?, MIT Sloan Management Review, 15, October, pp. 86–94.

[13]. Tajvidi, M., Richard, M.O., Wang, Y., Hajli, N. (2020) Brand co-creation through social commerce information sharing: The role of social media. Journal of Business Research, 121, pp.476-486.

[14]. Torelli, C.J., Monga, A.B., Kaikati, A.M. (2012) Doing poorly by doing good: Corporate social responsibility and brand concepts. Journal of Consumer Research, 38(5), pp.948-963.

[15]. Mckinsey. (2019) Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/∼/media/mckinsey/featured insights/china/howyoungchineseconsumersarereshapinggloballuxury/mckinsey-china-luxury-report- 2019-how-young-chinese-consumers-are-reshaping-global-luxury.ash

[16]. Kleine, S.S., Baker, S.M. (2004) An Integrative Review of Material Possession Attachment, Academy of Marketing Science Review, 8, pp. 1–35.

[17]. Park, C. W., Macinnis, D. J., Priester, J., Eisingerich, A. B., Iacobucci, D. (2010) Brand Attachment and Brand Attitude Strength: Conceptual and Empirical Differentiation of Two Critical Brand Equity Drivers, Journal of Marketing, 74(6), pp. 1–17.

[18]. Escalas, J.E., Bettman, J.R. (2005) Self-Construal, Reference Groups, and Brand Meaning, Journal of Consumer Research, 32(3), pp. 378–389.

[19]. Moore, D.J., Homer, P.M. (2008) Self-brand connections: The role of attitude strength and autobiographical memory primes, Journal of Business Research, 61, pp. 707-714.

[20]. Elbedweihy, A.M., Jayawardhena, C., Elsharnouby, M.H., Elsharnouby, T.H. (2016) Customer relationship building: The role of brand attractiveness and consumer–brand identification, Journal of Business Research, 69, pp. 2901-2910.

[21]. Escalas, J.E. (2004) Narrative Processing: Building Consumer Connections to Brands, Journal of Consumer Psychology, 14(1), pp. 168-180.

[22]. Moliner, M.A., Tirado, D.M., Guillén, M.E. (2018) Consequences of customer engagement and customer self-brand connection, Journal of Services Marketing, 32(4), pp. 387-399.

[23]. Kwon, E., Mattila, A.S. (2015) The Effect of Self–Brand Connection and Self-Construal on Brand Lovers’ Word of Mouth (WOM), Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 56(4), pp. 427-435.

[24]. Moisescu, O., Gică, O., Herle, F. (2022) Boosting eWOM through Social Media Brand Page Engagement: The Mediating Role of Self-Brand Connection, Behavioral Sciences, 12, p. 411.

[25]. Li, Y., Lu, C., Bogicevic, V., Bujisic, M. (2019) The effect of nostalgia on hotel brand attachment. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(2), 691-717.

[26]. O'Reilly, C. A., Chatman, J. (1986) Organizational commitment and psychological attachment: The effects of compliance, identification, and internalization on prosocial behavior, Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), pp. 492–499.

[27]. Albert, N., Merunka, D., Valette-Florence, P. (2013) Brand passion: Antecedents and consequences, Journal of Business Research, 66(7), pp. 904-909.

[28]. Bahri-Ammari, N., Van Niekerk, M., Ben Khelil, H., Chtioui, J. (2016) The effects of brand attachment on behavioral loyalty in the luxury restaurant sector, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(3), pp. 559-585.

[29]. Belén del Río, A., Vázquez, R., Iglesias, V. (2001) The effects of brand associations on consumer response, Journal of Consumer Marketing, 18(5), pp. 410-425.

[30]. Thomson, M., MacInnis, D.J. and Park, C.W. (2005) The Ties That Bind: Measuring the Strength of Consumers’ Emotional Attachments to Brands, Journal of Consumer Psychology, 15(1), pp. 77-91.

[31]. Holbrook, M.B., Hirschman, E.C. (1982) The Experiential Aspects of Consumption: Consumer Fantasies, Feelings, and Fun, Journal of Consumer Research, 9(2), pp. 132-140.

[32]. Schmitt, B. (2009) The concept of brand experience, Journal of Brand Management, 16(7), pp. 417–419.

[33]. Brakus, J.J., Schmitt, B.H., Zarantonello, L. (2009) Brand experience: what is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty?, Journal of Marketing, 73(3), pp. 52–68.

[34]. Verhoef, P.C., Verhoef, P.C., Lemon, K.N., Parasuraman, A., Roggeveen, A., Tsiros, M., Schlesinger, L.D. (2009) Customer experience creation: determinants, dynamics, and management strategies, Journal of Retailing, 85(1), pp. 31-41.

[35]. Lemon, K.N., Verhoef, P.C. (2016) Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey, Journal of Marketing, 80(6), pp. 69–96.

[36]. Fransen, M.L., Van Rompay, T.J., Muntinga, D.G. (2013) Increasing sponsorship effectiveness through brand experience, International Journal of Sports Marketing & Sponsorship, 14(2), pp. 112–125.

[37]. Berry, L.L., Carbone, L.P., Haeckel, S.H. (2002) Managing the total customer experience, International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 14(2), pp. 85–90.

[38]. Jung, L.H., Soo, K.M. (2012) The effect of brand experience on brand relationship quality, Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 16(1), pp. 87-98.

[39]. Barnes, S.J., Mattsson, J., Sorensen, F. (2014) Destination brand experience and visitor behavior: Testing a scale in the tourism context, Annals of Tourism Research, 48(C), pp. 121–139.

[40]. Brown, T.J., Barry, T.E., Dacin, P.A., Gunst, R.F. (2005) Spreading the word: Investigating antecedents of consumers’ positive word-of-mouth intentions and behaviors in a retailing context. Journal of the academy of marketing science, 33(2), pp.123-138.

[41]. Kim, D.H., Song, D. (2019) Can brand experience shorten consumers’ psychological distance toward the brand? The effect of brand experience on consumers’ construal level, Journal of Brand Management, 26(3).

[42]. Yu, X.L., Yuan, C.L., Kim, J., Wang, S., (2020) A new form of brand experience in online social networks: An empirical analysis, Journal of Business Research, 130, pp. 426-435.

[43]. Bogoviyeva, E., (2009) Brand development: The effects of customer brand co -creation on self -brand connection, The University of Mississippi.

[44]. DelVecchio, D., Smith, D.C. (2005) Brand-extension price premiums: the effects of perceived fit and extension product category risk, Journey of the Academy of Marketing Science, 33 (2), pp. 184–196.

[45]. Clarkson, J.T., Janiszewski, C., Cinelli, M.D. (2013) The desire for consumption knowledge, Journal of Consumer Research, 39 (6), pp. 1313–1329.

[46]. Oliver, R.L. (1999) Whence consumer loyalty?, Journal of Marketing, 63, pp.33-44.

[47]. Hwang, J., Kandampully, J. (2012) The role of emotional aspects in younger consumer-brand relationships, Journal of Product and Brand Management, 21(2), pp.98-108.

[48]. Assael, H. (1992) Consumer behavior and marketing action. Boston: PWS-Kent Publishing.

[49]. Tunjungsari, H.K., Syahrivar, J., Chairy, C. (2020) Brand loyalty as mediator of brand image-repurchase intention relationship of premium-priced, high-tech product in Indonesia. Journal Management Maranatha, 20(1), pp.21-30.

[50]. Dwivedi, A., Johnson, L.W., McDonald, R.E. (2015) Celebrity endorsement, self-brand connection and consumer-based brand equity, Journal of Product & Brand Management, 24(5), pp.449-461.

[51]. Reichheld, F.F. and Schefter, P. (2000) E-loyalty: your secret weapon on the Web, Harvard Business Review, pp.105-13.

[52]. Cronin, J.J. and Taylor, S.A. (1992) Measuring service quality: a reexamination and extension. Journal of Marketing. 56(7), pp. 55-68.

[53]. Tsai, S.P. (2014) Love and satisfaction drive persistent stickiness: investigating international tourist hotel brands, International Journal of Tourism Research, 16(6), pp.565-577.

[54]. Palmatier, R. W., Scheer, L. K., Steenkamp, J.B. E. M. (2007) Customer Loyalty to Whom? Managing the Benefits and Risks of Salesperson-Owned Loyalty. Journal of Marketing research, 44(2), pp.185-199.

[55]. Chaudhuri, A., Holbrook, M.B. (2001) The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: the role of brand loyalty. J. Mark. 65(2), pp.81–93.

[56]. Drennan, J., Bianchi, C., Cacho-Elizondo, S., Louriero, S., Guibert, N., Proud, W. (2015) Examining the role of wine brand love on brand loyalty: a multi-country comparison. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 49, pp.47–55.

[57]. Agarwal, S., Teas, R.K. (2001) Perceived value: mediating role of perceived risk. Journal of Marketing theory and Practice, 9(4), pp.1-14.

[58]. Kahneman, D., Tversky, A. (1979) On the interpretation of intuitive probability: A reply to Jonathan Cohen.

[59]. Coelho P.S., Rita, P., Santos Z.R. (2018) On the relationship between consumer-brand identification, brand community, and brand loyalty. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 43, pp.101-110.

[60]. So, K. K. F., King, C., Sparks, B. (2014) Customer Engagement With Tourism Brands: Scale Development and Validation, Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 38(3), pp. 304–329.

[61]. Tafesse, W. (2016) An experiential model of consumer engagement in social media, Journal of Product & Brand Management, 25(5), pp.424-434.

[62]. Hollebeek, L. D., Glynn, M. S., Brodie, R. J. (2014) Consumer brand engagement in social media: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. Journal of interactive marketing, 28(2), pp.149-165.

[63]. Kabadayi, S., Price, K. (2014) Consumer – brand engagement on Facebook: liking and commenting behaviors, Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 8(3), pp. 203-223.

[64]. Godey, B., Manthiou, A., Pederzoli, D., Rokka, J., Aiello, G., Donvito, R., Singh, R. (2016) Social media marketing efforts of luxury brands: Influence on brand equity and consumer behavior, Journal of Business Research, 69(12), pp. 5833–5841.

[65]. Hollenbeck, C. R., Kaikati, A. M. (2012) Consumers' use of brands to reflect their actual and ideal selves on Facebook. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 29(4), pp.395-405.

[66]. Li, N., Zhang, P. (2002) Consumer Online Shopping Attitudes and Behavior: An Assessment of Research, Eighth Americas Conference on Information System.

[67]. Armstrong, J.S., Overton, T.S. (1977) Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. Journal of marketing research, 14(3), pp.396-402.

[68]. Netemeyer, R.G., Krishnan, B., Pullig, C., Wang, G., Yagci, M., Dean, D., Ricks, J., Wirth, F. (2004) Developing and validating measures of facets of customer-based brand equity. Journal of business research, 57(2), pp.209-224.

[69]. Keller, K.L. (2001) Building customer-based brand equity: A blueprint for creating strong brands.

[70]. Schivinski, B., Christodoulides, G., Dabrowski, D. (2016) Measuring consumers' engagement with brand-related social-media content: Development and validation of a scale that identifies levels of social-media engagement with brands. Journal of advertising research, 56(1), pp.64-80.

[71]. Podsakoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B., Lee, J.Y., Podsakoff, N.P. (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of applied psychology, 88(5), p.879.

[72]. Podsakoff, P.M., Organ, D.W. (1986) Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of management, 12(4), pp.531-544.

[73]. Bagozzi, R. P., Yi, Y. (1988) On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the academy of marketing science, 16, pp.74-94.

[74]. Preacher, K. J., Hayes, A. F. (2008) Contemporary approaches to assessing mediation in communication research. In A. F. Hayes, M. D. Slater, & L. B. Snyder (Eds.), The Sage sourcebook of advanced data analysis methods for communication research. Sage Publications, Inc. pp.13-54.

[75]. Hudson, N. W., Roberts, B. W. (2016) Social investment in work reliably predicts change in conscientiousness and agreeableness: A direct replication and extension of Hudson, Roberts, and Lodi-Smith (2012). Journal of Research in Personality, 60, pp.12-23.

Cite this article

Ni,Y.;Mu,Y.;Lu,M.;Wang,J.;Chen,Z. (2024). The Effects of Brand-self Connection on the Willingness to Pay a Price Premium: A New Look at the Consumer–brand Relationship in the Chinese Luxury Market. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,82,12-27.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Financial Technology and Business Analysis

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Fournier, S. (1998) Consumers and their brands: Developing relationship theory in consumer research. Journal of consumer research, 24(4), pp.343-373.

[2]. van der Westhuizen, L.M. (2018) Brand loyalty: exploring self-brand connection and brand experience. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 27(2), pp.172-184.

[3]. McCracken, G. (1989) Who is the celebrity endorser? Cultural foundations of the endorsement process. Journal of consumer research, 16(3), pp.310-321.

[4]. Aggarwal, P. (2004) The effects of brand relationship norms on consumer attitudes and behavior. Journal of consumer research, 31(1), pp.87-101.

[5]. Grubb, E.L., Grathwohl, H.L. (1967) Consumer self-concept, symbolism and market behavior: A theoretical approach. Journal of marketing, 31(4), pp.22-27.

[6]. Rosenberg, M. (1989) Self-concept research: A historical overview. Social forces, 68(1), pp.34-44.

[7]. Escalas, J. E., Bettman, J. R. (2003) You are what they eat: The influence of reference groups on consumers' connections to brands. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 13(3), pp.339–348.

[8]. Aaker, J.L. (1997) Dimensions of brand personality. Journal of marketing research, 34(3), pp.347-356.

[9]. Ferraro, R., Escalas, J.E., Bettman, J.R. (2011) Our possessions, our selves: Domains of self-worth and the possession–self link. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 21(2), pp.169-177.

[10]. Vigneron, F., Johnson, L.W. (2004) Measuring perceptions of brand luxury. Journal of brand management, 11(6), pp.484-506.

[11]. Kapferer, J.N., Bastien, V. (2009) The specificity of luxury management: Turning marketing upside down. Journal of Brand management, 16(5-6), pp.311-322.

[12]. Dewar, N. (2004) What are brands good for?, MIT Sloan Management Review, 15, October, pp. 86–94.

[13]. Tajvidi, M., Richard, M.O., Wang, Y., Hajli, N. (2020) Brand co-creation through social commerce information sharing: The role of social media. Journal of Business Research, 121, pp.476-486.

[14]. Torelli, C.J., Monga, A.B., Kaikati, A.M. (2012) Doing poorly by doing good: Corporate social responsibility and brand concepts. Journal of Consumer Research, 38(5), pp.948-963.

[15]. Mckinsey. (2019) Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/∼/media/mckinsey/featured insights/china/howyoungchineseconsumersarereshapinggloballuxury/mckinsey-china-luxury-report- 2019-how-young-chinese-consumers-are-reshaping-global-luxury.ash

[16]. Kleine, S.S., Baker, S.M. (2004) An Integrative Review of Material Possession Attachment, Academy of Marketing Science Review, 8, pp. 1–35.

[17]. Park, C. W., Macinnis, D. J., Priester, J., Eisingerich, A. B., Iacobucci, D. (2010) Brand Attachment and Brand Attitude Strength: Conceptual and Empirical Differentiation of Two Critical Brand Equity Drivers, Journal of Marketing, 74(6), pp. 1–17.

[18]. Escalas, J.E., Bettman, J.R. (2005) Self-Construal, Reference Groups, and Brand Meaning, Journal of Consumer Research, 32(3), pp. 378–389.

[19]. Moore, D.J., Homer, P.M. (2008) Self-brand connections: The role of attitude strength and autobiographical memory primes, Journal of Business Research, 61, pp. 707-714.

[20]. Elbedweihy, A.M., Jayawardhena, C., Elsharnouby, M.H., Elsharnouby, T.H. (2016) Customer relationship building: The role of brand attractiveness and consumer–brand identification, Journal of Business Research, 69, pp. 2901-2910.

[21]. Escalas, J.E. (2004) Narrative Processing: Building Consumer Connections to Brands, Journal of Consumer Psychology, 14(1), pp. 168-180.

[22]. Moliner, M.A., Tirado, D.M., Guillén, M.E. (2018) Consequences of customer engagement and customer self-brand connection, Journal of Services Marketing, 32(4), pp. 387-399.

[23]. Kwon, E., Mattila, A.S. (2015) The Effect of Self–Brand Connection and Self-Construal on Brand Lovers’ Word of Mouth (WOM), Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 56(4), pp. 427-435.

[24]. Moisescu, O., Gică, O., Herle, F. (2022) Boosting eWOM through Social Media Brand Page Engagement: The Mediating Role of Self-Brand Connection, Behavioral Sciences, 12, p. 411.

[25]. Li, Y., Lu, C., Bogicevic, V., Bujisic, M. (2019) The effect of nostalgia on hotel brand attachment. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(2), 691-717.

[26]. O'Reilly, C. A., Chatman, J. (1986) Organizational commitment and psychological attachment: The effects of compliance, identification, and internalization on prosocial behavior, Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), pp. 492–499.

[27]. Albert, N., Merunka, D., Valette-Florence, P. (2013) Brand passion: Antecedents and consequences, Journal of Business Research, 66(7), pp. 904-909.

[28]. Bahri-Ammari, N., Van Niekerk, M., Ben Khelil, H., Chtioui, J. (2016) The effects of brand attachment on behavioral loyalty in the luxury restaurant sector, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(3), pp. 559-585.

[29]. Belén del Río, A., Vázquez, R., Iglesias, V. (2001) The effects of brand associations on consumer response, Journal of Consumer Marketing, 18(5), pp. 410-425.

[30]. Thomson, M., MacInnis, D.J. and Park, C.W. (2005) The Ties That Bind: Measuring the Strength of Consumers’ Emotional Attachments to Brands, Journal of Consumer Psychology, 15(1), pp. 77-91.

[31]. Holbrook, M.B., Hirschman, E.C. (1982) The Experiential Aspects of Consumption: Consumer Fantasies, Feelings, and Fun, Journal of Consumer Research, 9(2), pp. 132-140.

[32]. Schmitt, B. (2009) The concept of brand experience, Journal of Brand Management, 16(7), pp. 417–419.

[33]. Brakus, J.J., Schmitt, B.H., Zarantonello, L. (2009) Brand experience: what is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty?, Journal of Marketing, 73(3), pp. 52–68.

[34]. Verhoef, P.C., Verhoef, P.C., Lemon, K.N., Parasuraman, A., Roggeveen, A., Tsiros, M., Schlesinger, L.D. (2009) Customer experience creation: determinants, dynamics, and management strategies, Journal of Retailing, 85(1), pp. 31-41.

[35]. Lemon, K.N., Verhoef, P.C. (2016) Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey, Journal of Marketing, 80(6), pp. 69–96.

[36]. Fransen, M.L., Van Rompay, T.J., Muntinga, D.G. (2013) Increasing sponsorship effectiveness through brand experience, International Journal of Sports Marketing & Sponsorship, 14(2), pp. 112–125.

[37]. Berry, L.L., Carbone, L.P., Haeckel, S.H. (2002) Managing the total customer experience, International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 14(2), pp. 85–90.

[38]. Jung, L.H., Soo, K.M. (2012) The effect of brand experience on brand relationship quality, Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 16(1), pp. 87-98.

[39]. Barnes, S.J., Mattsson, J., Sorensen, F. (2014) Destination brand experience and visitor behavior: Testing a scale in the tourism context, Annals of Tourism Research, 48(C), pp. 121–139.

[40]. Brown, T.J., Barry, T.E., Dacin, P.A., Gunst, R.F. (2005) Spreading the word: Investigating antecedents of consumers’ positive word-of-mouth intentions and behaviors in a retailing context. Journal of the academy of marketing science, 33(2), pp.123-138.

[41]. Kim, D.H., Song, D. (2019) Can brand experience shorten consumers’ psychological distance toward the brand? The effect of brand experience on consumers’ construal level, Journal of Brand Management, 26(3).

[42]. Yu, X.L., Yuan, C.L., Kim, J., Wang, S., (2020) A new form of brand experience in online social networks: An empirical analysis, Journal of Business Research, 130, pp. 426-435.

[43]. Bogoviyeva, E., (2009) Brand development: The effects of customer brand co -creation on self -brand connection, The University of Mississippi.

[44]. DelVecchio, D., Smith, D.C. (2005) Brand-extension price premiums: the effects of perceived fit and extension product category risk, Journey of the Academy of Marketing Science, 33 (2), pp. 184–196.

[45]. Clarkson, J.T., Janiszewski, C., Cinelli, M.D. (2013) The desire for consumption knowledge, Journal of Consumer Research, 39 (6), pp. 1313–1329.

[46]. Oliver, R.L. (1999) Whence consumer loyalty?, Journal of Marketing, 63, pp.33-44.

[47]. Hwang, J., Kandampully, J. (2012) The role of emotional aspects in younger consumer-brand relationships, Journal of Product and Brand Management, 21(2), pp.98-108.

[48]. Assael, H. (1992) Consumer behavior and marketing action. Boston: PWS-Kent Publishing.

[49]. Tunjungsari, H.K., Syahrivar, J., Chairy, C. (2020) Brand loyalty as mediator of brand image-repurchase intention relationship of premium-priced, high-tech product in Indonesia. Journal Management Maranatha, 20(1), pp.21-30.

[50]. Dwivedi, A., Johnson, L.W., McDonald, R.E. (2015) Celebrity endorsement, self-brand connection and consumer-based brand equity, Journal of Product & Brand Management, 24(5), pp.449-461.

[51]. Reichheld, F.F. and Schefter, P. (2000) E-loyalty: your secret weapon on the Web, Harvard Business Review, pp.105-13.

[52]. Cronin, J.J. and Taylor, S.A. (1992) Measuring service quality: a reexamination and extension. Journal of Marketing. 56(7), pp. 55-68.

[53]. Tsai, S.P. (2014) Love and satisfaction drive persistent stickiness: investigating international tourist hotel brands, International Journal of Tourism Research, 16(6), pp.565-577.

[54]. Palmatier, R. W., Scheer, L. K., Steenkamp, J.B. E. M. (2007) Customer Loyalty to Whom? Managing the Benefits and Risks of Salesperson-Owned Loyalty. Journal of Marketing research, 44(2), pp.185-199.

[55]. Chaudhuri, A., Holbrook, M.B. (2001) The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: the role of brand loyalty. J. Mark. 65(2), pp.81–93.

[56]. Drennan, J., Bianchi, C., Cacho-Elizondo, S., Louriero, S., Guibert, N., Proud, W. (2015) Examining the role of wine brand love on brand loyalty: a multi-country comparison. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 49, pp.47–55.

[57]. Agarwal, S., Teas, R.K. (2001) Perceived value: mediating role of perceived risk. Journal of Marketing theory and Practice, 9(4), pp.1-14.

[58]. Kahneman, D., Tversky, A. (1979) On the interpretation of intuitive probability: A reply to Jonathan Cohen.

[59]. Coelho P.S., Rita, P., Santos Z.R. (2018) On the relationship between consumer-brand identification, brand community, and brand loyalty. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 43, pp.101-110.

[60]. So, K. K. F., King, C., Sparks, B. (2014) Customer Engagement With Tourism Brands: Scale Development and Validation, Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 38(3), pp. 304–329.

[61]. Tafesse, W. (2016) An experiential model of consumer engagement in social media, Journal of Product & Brand Management, 25(5), pp.424-434.

[62]. Hollebeek, L. D., Glynn, M. S., Brodie, R. J. (2014) Consumer brand engagement in social media: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. Journal of interactive marketing, 28(2), pp.149-165.

[63]. Kabadayi, S., Price, K. (2014) Consumer – brand engagement on Facebook: liking and commenting behaviors, Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 8(3), pp. 203-223.

[64]. Godey, B., Manthiou, A., Pederzoli, D., Rokka, J., Aiello, G., Donvito, R., Singh, R. (2016) Social media marketing efforts of luxury brands: Influence on brand equity and consumer behavior, Journal of Business Research, 69(12), pp. 5833–5841.

[65]. Hollenbeck, C. R., Kaikati, A. M. (2012) Consumers' use of brands to reflect their actual and ideal selves on Facebook. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 29(4), pp.395-405.

[66]. Li, N., Zhang, P. (2002) Consumer Online Shopping Attitudes and Behavior: An Assessment of Research, Eighth Americas Conference on Information System.

[67]. Armstrong, J.S., Overton, T.S. (1977) Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. Journal of marketing research, 14(3), pp.396-402.

[68]. Netemeyer, R.G., Krishnan, B., Pullig, C., Wang, G., Yagci, M., Dean, D., Ricks, J., Wirth, F. (2004) Developing and validating measures of facets of customer-based brand equity. Journal of business research, 57(2), pp.209-224.

[69]. Keller, K.L. (2001) Building customer-based brand equity: A blueprint for creating strong brands.

[70]. Schivinski, B., Christodoulides, G., Dabrowski, D. (2016) Measuring consumers' engagement with brand-related social-media content: Development and validation of a scale that identifies levels of social-media engagement with brands. Journal of advertising research, 56(1), pp.64-80.

[71]. Podsakoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B., Lee, J.Y., Podsakoff, N.P. (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of applied psychology, 88(5), p.879.

[72]. Podsakoff, P.M., Organ, D.W. (1986) Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of management, 12(4), pp.531-544.

[73]. Bagozzi, R. P., Yi, Y. (1988) On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the academy of marketing science, 16, pp.74-94.

[74]. Preacher, K. J., Hayes, A. F. (2008) Contemporary approaches to assessing mediation in communication research. In A. F. Hayes, M. D. Slater, & L. B. Snyder (Eds.), The Sage sourcebook of advanced data analysis methods for communication research. Sage Publications, Inc. pp.13-54.

[75]. Hudson, N. W., Roberts, B. W. (2016) Social investment in work reliably predicts change in conscientiousness and agreeableness: A direct replication and extension of Hudson, Roberts, and Lodi-Smith (2012). Journal of Research in Personality, 60, pp.12-23.