1. Introduction

In a journalistic investigation about the British immigration policy that was determined to have contributed to a labor shortage, Bourgery-Gonse [1] represented the state of earnings and status of various workforces as well as labor mobility inside the European Union. I believe that the state of the labor market is a true indicator of the state of the economy, and this, along with the significant effects of Brexit, has motivated me to investigate how the labor market is changing in this particular setting.

In 1972, the UK formally acceded to the EU. On a larger scale, the union has provided the UK with significant economic advantage and political protection. Free trade among the participating nations boosted market rivalry and encouraged productivity growth (Veld [2]). The UK's employment chances for multinational positions have increased as the primary exporter to the EU (Crafts [3]). But the voices of opposition never stop. In 2013, in response to growing Euroskepticism within the Conservative Party, David Cameron first pledged a referendum on whether the UK should leave the EU. The UK government created a preliminary plan following a vote by the general public, and the transition period began in 2018 (Macshane [4]). The UK officially exited the EU in February 2020.

To convince the UK to quit the EU after years of integration and cooperation, significant forces must be left behind. The Eurozone debt crisis and the migration issue are generally acknowledged as the two main catalysts that directly caused Brexit (Adam [5]). Due to the complex factors that led to its formation, the debt crisis will not be further examined. While I would concentrate on this research on the migrant issue, which is another important driving force.

The economic crisis in the Eurozone in the 2010s caused a steady flow of European immigrants into the UK. Even worse, the start of the Syrian civil war sparked a tremendous influx of refugees into Europe. Because of an EU treaty that holds member states legally liable for accepting refugees under quotas, the UK was compelled to take in migrants (Thompson [6]). These arrivals have seriously disrupted social order and incited intense hostility among locals. The UK government implemented new immigration laws in January 2021 in response to the urgent need for more stringent immigrant intake. Economic concern has traditionally centered on the immigration economy because of the potential for persistent and significant shocks to the local culture and economy caused by the influx of people. The change in immigration policy could have a significant impact on the job economy, in particular. This article is dedicated to an in-depth exploration more about this recent move and how it will affect the local labor market in the UK both now and in the future.

2. UK labor market

The EU's refugee quota system was declared to be terminated under the new policy, and the UK simultaneously passed its own refugee law to stop undocumented immigration (UK Government [7]). While this was going on, the admittance criterion for skilled workers from outside the EU was lowered from RQF6 to RQF3, suggesting that the UK intended to take in more aristocrats (Zenia [8]). A part of applicants who were previously unavailable to the UK (RQF3-RQF5) are now licensed as a result of the expanded definition of "high-quality workforce" introduced by this revised policy. I'm naturally driven to divide the UK labor market into the following three categories to pursue my research in light of this change:

High-end labor market (RQF6-RQF8): This group of workers comprises people with advanced degrees and high salaries. The policy change would not have an impact on their entrance to the UK.

Mid-end labor market (RQF3-RQF5): Under the new policy, employees in this second-tier labor market are now referred to as "high skilled workers" and are therefore allowed to enter the UK labor market to look for work.

Market for low-end workers (RQF1-RQF2): This labor class includes refugees and other low-skilled employees who are typically dispersed among lower-paying and labor-intensive industries. This sector's foreign employees are still prohibited from entering the UK by policy.

The labor segmentation theory supports the above divide. All industrialized economies, according to Plummer [9], have a specific market segmentation that is made up of both high- and low-skilled workers.

3. Research Questions

My research questions are thus derived after breaking down the entire UK labor market into three tiers, which may allow me to gain a clearer and more stratified understanding of those crucial components of each labor market:

RQ1: In light of the dramatic population changes brought on by Brexit, I want to learn more about how the policy changes for each segment are predicted to affect the labor supply and labor demand, as well as how they will affect the equilibrium long-term wage level and the number of workers employed in the UK labor market.

RQ2: Since full employment wouldn't always be the case in the actual world, I'm interested in the after-Brexit structural unemployment rate, which is defined as unemployment brought on by wage rigidity and job rationing. It is impractical to look at the revised natural unemployment rate from a long-term perspective given how recently the formal Brexit occurred. As a result, I will concentrate on the short term and use the "sticky" wage level as an exogenous variable that by no means succeeded in adjusting to the equilibrium wage level. The impact of this real wage rigidity on the structural unemployment rate in each market will next be studied.

4. Argument & Analysis

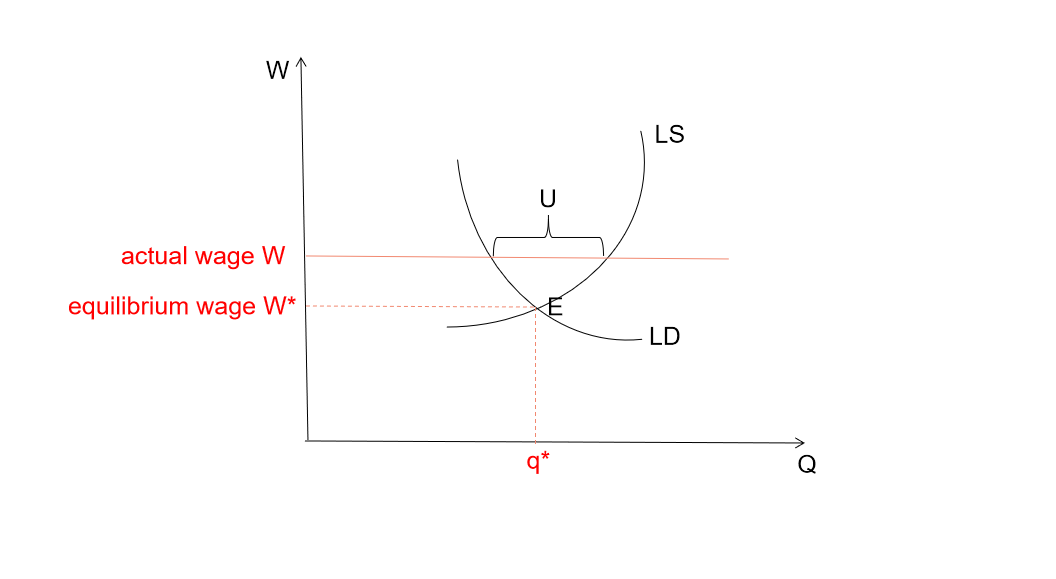

Looking into my research question, the model of labor market is employed in the following analysis (Figure 1). In this model, x-axis and y-axis represent the quantity of labor (Q) and real wage (W) respectively, which are two endogenous variables. An elastic supply curve is assumed since in practice, a higher wage increases the benefit of job finding. An upward-sloping labor supply curve is drawn (LS) to interpret this positive relationship, while the labor demand curve (LD) slopes down because a lower real wage cost employers less and increase the willingness to enlarge labor demand by firms in UK. The equilibrium (E*) is the intersection point of LS and LD, referring to the full-employed labor market with only natural unemployment. To provide a more realistic reflection of real world, the average wages for high-end, mid-end and low-end markets are assumed to go from high to low (i.e., w1>w2>w3). Taking the actual real wage as a predetermined factor in short run, this level is assumed to be stuck above the equilibrium wage due to efficiency wage and the minimum wage law (will be explained later). Structural unemployment can be measured by the gap between LS and LD, depicting an excessive labor supply and deficient labor demand. After introducing the initial model, I will see the detailed scenarios in three labor markets:

Figure 1: model of labor market

4.1. High-end labor market

In the high-end labor market, advanced talents commonly play critical roles among enterprises. It is necessary for the companies to employ efficiency wage theory to increase working initiative and reduce shirking. Consequently, the above-equilibrium wage W1 is drawn in Figure 2 below.

For the demand side, British firms are not likely to change their operation and business scales in the short term. Although nearly three-quarters of firms belonging to the high-paying sectors believe that the corporate operation will suffer from an adverse influence after Brexit, tiny changes in recruitment plans are reckoned to be made by ONS, which means that the impact on migration rate will be subtle. Since the staff size in the high-end labor market is highly correlated to recruitment schedules, employee demand may remain at the previous level (Abby [10]). Hence, the LD curve stay at the original position.

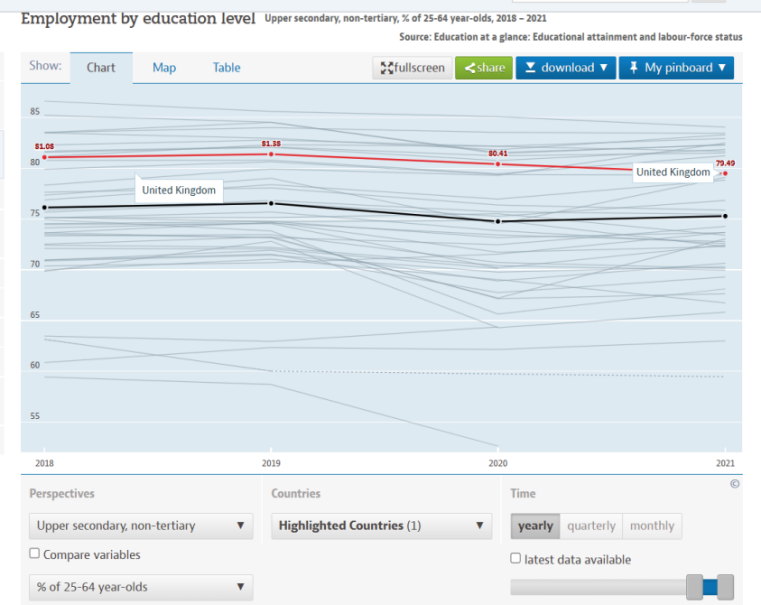

For the supply side, the evidences relevant to the relationship between Brexit and changes to the supply of skilled labor are controversial. According to OECD (Figure 3), the number of local employees with higher than the upper secondary education has slightly increased in the last four years after Brexit. However, this conclusion could be superficial since this increment could result from the increased population base of domestic workers. Regarding the limitation of data, it cannot authentically reflect the skilled labor according to the RQF standards. Benedi [11] believes that since the anti-immigrant sentiment and populist discourse have surged ex and post-Brexit, the skilled labor of Polish (the largest source of EU migrants) is more inclined to leave the UK. Furthermore, the experiences of highly-skilled labor within various industries exhibit heterogeneity. The number of scientists decreased by 14% while the skilled immigrant in the medical industry has significantly increased by 20% according to ONS. Considering both sides, I take a conservative approach and assume an unchanged supply of skilled labor in this segment, keeping the LS curve unchanged. Thus, the equilibrium point of the high-end labor market is expected to stay at the initial point E. No significant alteration to unemployment rates is anticipated, and the unemployment rate remained at U.

Figure 2: model of high-end labor market

Figure 3: Source:OECD

4.2. Mid-end labor market

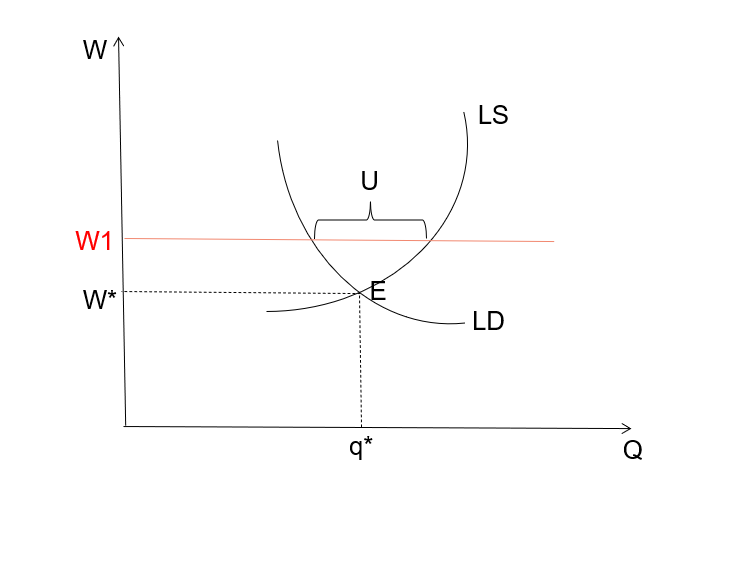

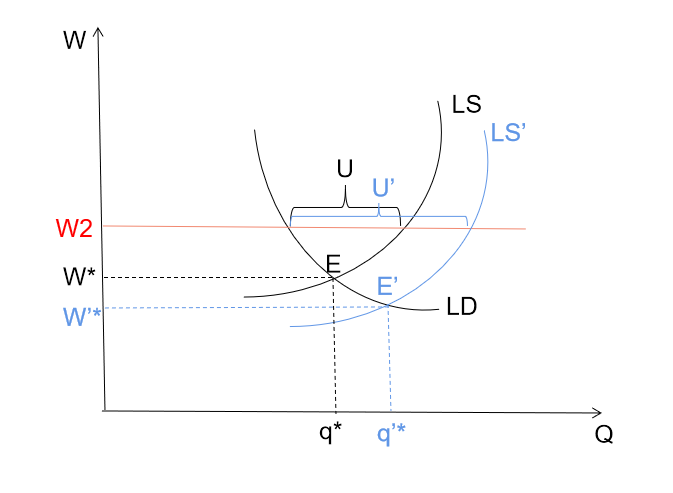

Education and skills training is less advanced among mid-end market labors than high-end ones, usually distributed in secondary industries and have foundation degrees (NCC [12]). As conditions for future work visa applications in the UK have been relaxed, it is easier to get a work visa if the job skills and English requirements are met. The basic threshold, RQF3 or above, accounts for around 63% of all jobs, showing that more than half of the workers are eligible for a skilled work visa in the UK labor market (Jonathan & John [13]). As more people qualify for work visas and a surging inflow of migrant workers, the LS curve in the mid-end labor market shifts rightwards. While the LD curve is assumed to be invariant for the same reason in the high-end labor market. Similarly, an efficiency wage makes the wage fixed above the equilibrium point.

The new equilibrium point exists at a higher q’* and a lower W’*. The gap between the LS’ and the LD curve becomes wide with the sticky wage that is the average level of the quality labor force, w2, between the high-end’s average wage and the low-end’s average wage. Therefore, the expected structural unemployment rate would rise from the initial U to U’.

Figure 4: model of mid-end labor market

Figure 5: Labor force in the UK, Source: ONS

4.3. Low-end labor market

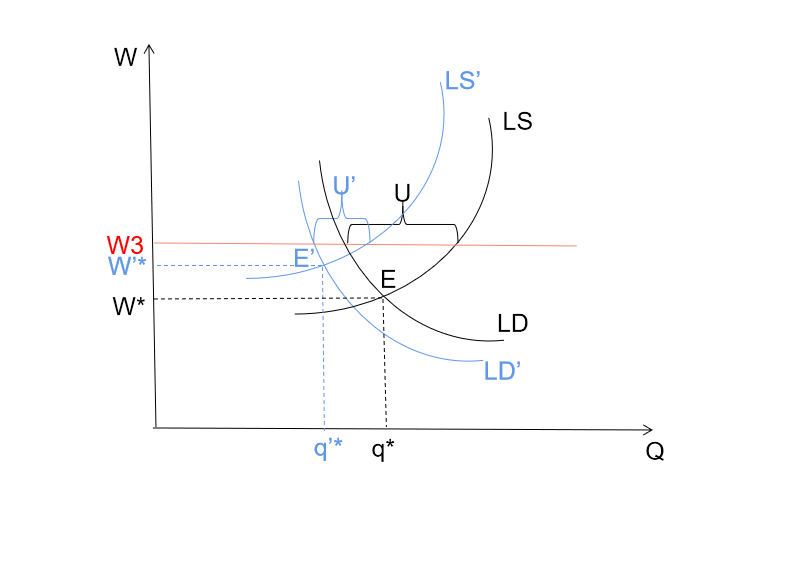

The most complicated case comes in the low-end labor market, which refers to the labor force from RQF1 to RQF2 and refugees. Initially, the supply and demand curves for labor intersect at the equilibrium real wage E. Due to wage rigidity, wages failed to adjust to a level where labor supply equals labor demand, leading to an unemployment of U before the policy change (Figure 6).

The new immigration system seems to cause a significant decline in labor supply. The results of the ONS Annual Population Survey [14] showed a net loss in workers of around 330,000 by June 2022, most of which are low-end workers since a large proportion of low-qualified workers from EU countries and substandard refugees are not allowed to remain in the UK due to policy changes (Portes and Springford [15]). For instance, in kitchen porters and warehouse staff positions, Britain's employers are struggling with the worst staff shortages since the late 1990s (The Guardian [16]).

Meanwhile, demand in the low-end labor market is falling as well. According to a UK government [7] report, over 4,400 cross-border companies planned to move their operations out of the UK or reduce trade volumes since the referendum in 2016. As most of the jobs these labor-intensive factories offered align with RQF1-2 levels, the demand for lower-end labor will likely to drop as factories are withdrawn.

Under this situation, both supply and demand curves in the model shift left, making it difficult to study the equilibrium point without determining how much the two curves have fallen. However, according to the REC's analysis [17], employers in the low-end labor market gradually struggled to fill in all the posts. Accordingly, I make the hypothesis that the downward trend in supply in the UK's low-quality labor market is greater than that in demand.

Figure 6: model of low-end labor market

Based on this assumption, I first analyze the change of the equilibrium point. The graph above demonstrates that the equilibrium point moves upwards as ΔS is greater than ΔD. From the long term, the wage level will be followed by an upward shift and the number of employed workers will decrease.

Next, I analyze the change of the unemployment rate through the intersection distance. Worth mentioning, due to the Minimum-wage Law -- firms are asked to set the minimum wage by government exceeding the equilibrium wage of unskilled workers, the real wage line w3 is set higher than the equilibrium point. The gap is shorten compared to the period before the new immigration policy was enacted, indicating that the unemployment rate has fallen. This is consistent with reality: Reported by the ONS Unemployment Rate [18], 2021 witnessed a 0.3% drop of unemployment in the low-end labor market since Brexit, suggesting my previous hypothesis is valid.

5. Recommendations

My prior deductions indicate that while the high-end labor market is expected to be little affected by changes in immigration laws, the mid- and low-end labor markets may see major changes.

A present decrease in low-end labor entering the UK is observed, coinciding with a decrease in the unemployment rate. It appears that restricting immigrant admittance is effective in reducing employment strain. On the other hand, a sustained decline in the availability of low-wage labor may have unfavorable long-term repercussions. Low-level roles can barely be filled by native workers alone, which progressively results in a labor shortage and inadequate productivity. To alleviate this problem, the government is contemplating the following suggestions:

First, the government ought to provide financial aid for the introduction of automated production. Companies can reduce their dependency on labor by applying automation to production processes, which will increase demand for mid-level employees who can more easily adjust to a workplace that is becoming more automated (Madeleine et al. [19]). This transition can make it easier for low-end labor-market industries to become ones that need medium-skilled personnel, which would simultaneously reduce the total need for low-skilled workers and ease competitive pressure in the mid-end job market. Additionally, the minimum wage for the entire workforce may be gradually raised by the UK government. Although it is frequently argued that raising the minimum wage might result in a higher employment cost, which would cause businesses to hire fewer workers, Hull and Walters [20] discovered that raising the minimum wage, acting as an incentive mechanism, will attract more native British workers to enter the low-end labor market and, in the long run, cultivate self-sufficiency in the UK's low-end labor force.

Immigration laws have lowered the entry restrictions for the mid-end sector, which has increased unemployment. In order to address this issue, I suggest the following solutions:

The Labor Union could first push for the implementation of a maximum working week quota. This suggests a reduction in the number of hours that employees work, which prompts businesses to hire more people to make up for the lost time. In the end, additional job openings would result from this increase in recruitment. Second, if unemployment is an issue, the government may implement advantageous fiscal measures to cut taxes. Reduced taxes will enhance household disposable income, which will increase consumption and the demand for goods. As a result, businesses will increase output in response (Rendahl [21]). According to Okun's Law, there should be a negative correlation between total output and unemployment. As a result, the unemployment rate is projected to decrease. Thus, the surplus of middle-skilled labor could be reduced as a result.

Beyond the aforementioned practical concerns, it is impossible to disregard constraints in my model and data. The employment numbers may have been greatly affected, particularly in businesses like travel and trading, because the Brexit period and the COVID-19 pandemic occurred at the same time. A high inflation rate also results in a substantial disparity between the wage levels in various markets. In order to lessen the effects of inflation, I aim to choose average actual salary data rather than nominal wage throughout the entire data gathering process. I also rely on sources of worker mobility that are only impacted by immigration policy in order to make my conclusions as verifiable as feasible.

6. Conclusion

This essay demonstrates how the UK labor market has been impacted by immigration policies following Brexit. Employment numbers may have been greatly affected, especially in businesses like tourism and trade, because the Brexit era and the COVID-19 pandemic occurred at the same time. High inflation may also result in considerable variations in wage levels between markets. I use average real salaries rather than nominal wages throughout the research to lessen the effects of inflation and rely on sources of labor mobility that are only impacted by immigration policies to support this finding.

References

[1]. Bourgery-Gonse, T. (2023, February 27). Brexit: UK immigration system found to contribute to labour shortages. EURACTIV. Retrieved from https://www.euractiv.com/section/economy-jobs/news/brexit-uk-immigration-system-found-to-contribute-to-labour-shortages/

[2]. Veld, J. (2019) ‘The economic benefits of the EU Single Market in goods and services’, Journal of Policy Modeling,41, pp. 803–818. doi:10.1016/j.jpolmod.2019.06.004.

[3]. Crafts, N. (2012) 'British relative economic decline revisited: The role of competition', Explorations in Economic History, 49(1), pp. 17–29. doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2011.06.004.

[4]. Macshane, D. (2021) 'Britain enters the era of Brexit', International Affairs, 97(4), pp. 1239–1248. doi:10.1093/ia/iiab102.

[5]. Adam, R.G. (2020) Brexit: Causes and Consequences. 1st ed. Springer International Publishing. Available at: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat01010a&AN=xjtlu.0001742046&site=eds-live&scope=site.

[6]. Helen Thompson. (2021) Inevitability and contingency: The political economy of Brexit, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 2017, Vol. 19, pp. 434-449.

[7]. UK Government (2021) EU Exit Business Readiness Monthly Report: September 2021. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/eu-exit-business-readiness-monthly-report-september-2021

[8]. Zenia,C. (2021) 2021 IMMIGRATION CHANGES Available at: https://www.tenentrepreneurs.org/blog/2021-immigration changes#:~:text=Regulated%20Qualifications%20Framework%20%28RQF%29%20level%3A%20In%20order%20to,level%203%20%28roles%20skilled%20at%20an%20A%20level%29

[9]. Plummer, R.C. (2019) ‘Labor market segmentation and the demand for EU migrant workers: a comparative study of Sweden and the United Kingdom’. Available at: https://search-ebscohost com.ez.xjtlu.edu.cn/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsble&AN=edsble.784378&site=eds-live&scope=site

[10]. Abby, S. (2016) ‘Impact of EU exit on our UK industry forecasts’ Economic Outlook, 40(3), pp. 10–12. doi:10.1111/1468-0319.12229.

[11]. Benedi Lahuerta, S. and Iusmen, I. (2021) ‘EU nationals’ vulnerability in the context of Brexit: the case of Polish nationals’, Journal of Ethnic & Migration Studies, 47(1), pp. 284–306. Doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1710479.

[12]. NCC. (2016) What are the Differences between QCF, RQF and NVQ. Available at: https://www.ncchomelearning.co.uk/blog/what-are-the-differences-between-qcf-rqf-and-nvq-infographic/

[13]. Jonathan, P. and John, S. (2023) ‘The impact of the post-Brexit migration system on the UK labour market’, Contemporary Social Science, 38(1), pp. 1-16. doi: 10.1080/21582041.2023.2192516

[14]. Office for National Statistics (2021) Annual population survey (APS) QMI. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/methodologies/annualpopulationsurveyapsqmi

[15]. Portes, J. & Springford, J. (2023) Early impacts of the post-Brexit immigration system on the UK labour market. Centre for European Reform. Available at: https://www.cer.eu/publications/archive/policy-brief/2023/early-impacts-post-brexit-immigration-system-uk-labour-market

[16]. The Guardian (2021) UK employers struggle with worst labour shortage since 1997. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2021/oct/19/uk-employers-struggle-with-worst-labour-shortage-since-1997

[17]. REC (Recruitment & Employment Confederation) (2019) Can the UK Labour Force Meet Demand After Brexit? Available at: https://www.rec.uk.com/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/456215/REC_Labour_Market_Report_-_Can_the_UK_Labour_Force_Meet_Demand_After_Brexit.pdf

[18]. Office for National Statistics (2021) Unemployment Rate (aged 16 and over, seasonally adjusted): %. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peoplenotinwork/unemployment/timeseries/mgsx/lms

[19]. Madeleine, S. et al. (2022) How is the End of Free movement Affecting the Low-wage Labor Force in the UK. Available at: https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/reports/how-is-the-end-of-free-movement-affecting-the-low-wage-labour-force-in-the-uk/p

[20]. Hull, P., Kolesár, M. and Walters, C. (2022) ‘Labour by Design: Contributions of David Card, Joshua Angrist, and Guido Imbens’. doi:10.1111/sjoe.12505.

[21]. RENDAHL, P. (2016) ‘Fiscal Policy in an Unemployment Crisis’, The Review of Economic Studies, 83(3 (296)), pp. 1189–1224. Available at: https://search-ebscohost-com.ez.xjtlu.edu.cn/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsjsr&AN=edsjsr.43869564&site=eds-live&scope=site

Cite this article

Zhu,Q. (2024). The Impact of Immigration Policy on the British Labor Market after Brexit. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,92,60-70.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Financial Technology and Business Analysis

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Bourgery-Gonse, T. (2023, February 27). Brexit: UK immigration system found to contribute to labour shortages. EURACTIV. Retrieved from https://www.euractiv.com/section/economy-jobs/news/brexit-uk-immigration-system-found-to-contribute-to-labour-shortages/

[2]. Veld, J. (2019) ‘The economic benefits of the EU Single Market in goods and services’, Journal of Policy Modeling,41, pp. 803–818. doi:10.1016/j.jpolmod.2019.06.004.

[3]. Crafts, N. (2012) 'British relative economic decline revisited: The role of competition', Explorations in Economic History, 49(1), pp. 17–29. doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2011.06.004.

[4]. Macshane, D. (2021) 'Britain enters the era of Brexit', International Affairs, 97(4), pp. 1239–1248. doi:10.1093/ia/iiab102.

[5]. Adam, R.G. (2020) Brexit: Causes and Consequences. 1st ed. Springer International Publishing. Available at: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat01010a&AN=xjtlu.0001742046&site=eds-live&scope=site.

[6]. Helen Thompson. (2021) Inevitability and contingency: The political economy of Brexit, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 2017, Vol. 19, pp. 434-449.

[7]. UK Government (2021) EU Exit Business Readiness Monthly Report: September 2021. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/eu-exit-business-readiness-monthly-report-september-2021

[8]. Zenia,C. (2021) 2021 IMMIGRATION CHANGES Available at: https://www.tenentrepreneurs.org/blog/2021-immigration changes#:~:text=Regulated%20Qualifications%20Framework%20%28RQF%29%20level%3A%20In%20order%20to,level%203%20%28roles%20skilled%20at%20an%20A%20level%29

[9]. Plummer, R.C. (2019) ‘Labor market segmentation and the demand for EU migrant workers: a comparative study of Sweden and the United Kingdom’. Available at: https://search-ebscohost com.ez.xjtlu.edu.cn/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsble&AN=edsble.784378&site=eds-live&scope=site

[10]. Abby, S. (2016) ‘Impact of EU exit on our UK industry forecasts’ Economic Outlook, 40(3), pp. 10–12. doi:10.1111/1468-0319.12229.

[11]. Benedi Lahuerta, S. and Iusmen, I. (2021) ‘EU nationals’ vulnerability in the context of Brexit: the case of Polish nationals’, Journal of Ethnic & Migration Studies, 47(1), pp. 284–306. Doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1710479.

[12]. NCC. (2016) What are the Differences between QCF, RQF and NVQ. Available at: https://www.ncchomelearning.co.uk/blog/what-are-the-differences-between-qcf-rqf-and-nvq-infographic/

[13]. Jonathan, P. and John, S. (2023) ‘The impact of the post-Brexit migration system on the UK labour market’, Contemporary Social Science, 38(1), pp. 1-16. doi: 10.1080/21582041.2023.2192516

[14]. Office for National Statistics (2021) Annual population survey (APS) QMI. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/methodologies/annualpopulationsurveyapsqmi

[15]. Portes, J. & Springford, J. (2023) Early impacts of the post-Brexit immigration system on the UK labour market. Centre for European Reform. Available at: https://www.cer.eu/publications/archive/policy-brief/2023/early-impacts-post-brexit-immigration-system-uk-labour-market

[16]. The Guardian (2021) UK employers struggle with worst labour shortage since 1997. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2021/oct/19/uk-employers-struggle-with-worst-labour-shortage-since-1997

[17]. REC (Recruitment & Employment Confederation) (2019) Can the UK Labour Force Meet Demand After Brexit? Available at: https://www.rec.uk.com/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/456215/REC_Labour_Market_Report_-_Can_the_UK_Labour_Force_Meet_Demand_After_Brexit.pdf

[18]. Office for National Statistics (2021) Unemployment Rate (aged 16 and over, seasonally adjusted): %. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peoplenotinwork/unemployment/timeseries/mgsx/lms

[19]. Madeleine, S. et al. (2022) How is the End of Free movement Affecting the Low-wage Labor Force in the UK. Available at: https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/reports/how-is-the-end-of-free-movement-affecting-the-low-wage-labour-force-in-the-uk/p

[20]. Hull, P., Kolesár, M. and Walters, C. (2022) ‘Labour by Design: Contributions of David Card, Joshua Angrist, and Guido Imbens’. doi:10.1111/sjoe.12505.

[21]. RENDAHL, P. (2016) ‘Fiscal Policy in an Unemployment Crisis’, The Review of Economic Studies, 83(3 (296)), pp. 1189–1224. Available at: https://search-ebscohost-com.ez.xjtlu.edu.cn/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsjsr&AN=edsjsr.43869564&site=eds-live&scope=site