1. Introduction

Sino-U.S. relations are among the key great power relationships that profoundly impact the global order.[1] Although the comprehensive strengths of China and the United States remain at different levels, and their interests are complementary in some areas, they are primarily competitors in core sectors, particularly in finance, high technology, and military fields. From a political strategy perspective, the United States pursues a zero-sum game approach, whereas China advocates a win-win cooperation strategy. These differing global political strategies and the divergence of political interests have exacerbated Sino-U.S. differences. Focusing on key sectors, the United States, with the world's largest financial capital base, leverages its hegemonic mechanisms to extract global benefits. For a long time, the U.S. has relied on low-cost Chinese products and low-interest U.S. Treasury bonds to achieve periodic, low-cost global financial capital expansion. Meanwhile, China has rapidly developed in the financial, high-tech, and military sectors, fully participating in the global competition for high economic value-added benefits. This has led to a significant transformation in China's industrial structure, resulting in heightened tensions between China and the Western bloc led by the United States. As a result, the U.S.'s hegemonic mechanisms have lost their sustainability. In this strategic competition, the United States represents the primary force of contradiction, while China is the secondary force.

For a long time, the United States has exported low-interest U.S. Treasury bonds through its trade deficit, maintaining its position as the world's leading reserve currency through the "Triffin Dilemma" mechanism. However, this has exacerbated the hollowing out of U.S. domestic industries and the virtualization of capital. A large portion of U.S. manufacturing has relocated to low-cost countries, leading to a significant loss of manufacturing jobs domestically. The outflow of the real economy has led to an influx of domestic capital into capital markets, and the United States has leveraged its military hegemony to achieve global expansion of financial capital. U.S. social spending has long relied on the issuance of Treasury bonds, rather than being jointly borne by businesses and the government, resulting in a sharp increase in the scale of U.S. debt and triggering a debt bubble and stock market bubble. For years, China has provided the U.S. with low-cost products, suppressing U.S. social inflation. However, the added physical assets have been re-priced by U.S. financial capital, with U.S. capital reaping the absolute industrial returns, while China's actual industrial returns have been compressed. This has led to a flow of Chinese social funds into speculative industries such as real estate and the stock market to achieve normal returns, resulting in bubbles in China's stock market and real estate sector. Furthermore, the large amount of foreign debt has constrained China's development, making it subject to U.S. influence.

After the 2008 financial crisis, the U.S. implemented a reindustrialization policy, bringing back a significant amount of manufacturing to its domestic economy. This forced China's coastal regions to undergo "deindustrialization," leading to a surge in unemployment and an oversupply of products. Through long-term accumulation during its reform and opening-up period, China has become the world's second-largest financial capital power and the largest industrial capital power, leading to an excess of both financial and industrial capital. The severe surplus of products and capital prompted China to embark on an "outward" strategy, altering its economic circulation pattern and seeking reasonable global economic benefits. This move has touched upon the interests of the Western bloc led by the United States. Consequently, Sino-U.S. strategic competition has become increasingly fierce, entering a new Cold War era where the Western bloc, led by the United States, is constantly seeking to decouple from China to protect the global interests of its vested interest groups.

2. Overview of Sino-U.S. Strategic Competition

Competition and cooperation have always been integral to the relationship between China and the United States. Prior to the 2008 financial crisis, China supported the United States by exporting low-cost products and capital, which helped sustain America's overissued currency and maintain a low-inflation society. During this period, Sino-U.S. relations were primarily characterized by cooperation, with the U.S. even proposing the concept of "G2" governance and recognizing China as a leader among emerging nations. However, following the financial crisis, China's strategies began to impinge upon core Western interests, marking a critical turning point in Sino-U.S. relations.

In 2012, the United States introduced the "Asia-Pacific Rebalance" strategy, deploying military forces in regions surrounding China to curb China's maritime power expansion and capital outflows, thereby safeguarding U.S. hegemonic interests. In December 2017, the United States, in its National Security Strategy report, designated China as a "revisionist state" and a strategic competitor,[2] launching a trade war against China, sanctioning numerous Chinese companies, and restricting Chinese capital. The U.S. imposed tariffs on $550 billion worth of Chinese goods, affecting industries and products that include, but are not limited to, steel, aluminum, energy, "critical industrial technologies," consumer goods, and agricultural products.[3] The Biden administration has reinforced export controls on China, extended tariff exemptions on 352 Chinese import items, and restricted the export of advanced technologies such as chips and lithography machines to China, aiming to comprehensively hinder China's economic and technological development.

In response to U.S. containment strategies, China has advanced the Made in China 2025 initiative, continuously enhancing technological innovation to overcome industrial technological bottlenecks and weaken the strategic suppression led by the Western bloc, particularly the United States. The Chinese government has significantly invested in high-tech sectors, promoting the independent research and development of critical technologies such as chips, lithography machines, and engines, thereby reducing reliance on imported technologies. In the military sphere, China has developed advanced weapons such as aircraft carriers, stealth fighters, and drones, and has leased overseas military ports to expand its maritime power, breaking through the U.S. military encirclement. In the financial domain, China has expanded its overseas industrial investments and signed bilateral currency swap agreements with 29 countries, with a total swap scale exceeding 4 trillion yuan, thereby eroding the U.S. dollar's share in global settlements.

As Sino-U.S. strategic competition continues to intensify, compounded by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, both countries' economies and the global economy have been affected to varying degrees. In 2023, China's GDP growth rate fell short of forecasts by 1.1%, and overall exports slowed, with a significant decline in exports to the United States. According to data released by the U.S. Department of Commerce, the U.S. GDP growth rate for 2023 was 2.5%, with total goods trade amounting to $5.192 trillion, down 4.5% year-on-year. Goods exports declined by 2.2%, while goods imports decreased by 5.9% year-on-year.[4] The United States has initiated a wave of trade protectionism worldwide, restricting goods and technology trade, leading to an escalation in Sino-U.S. strategic competition. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has forecasted that this strategic competition between China and the United States will profoundly impact global economic growth, with the global economy expected to slow to a growth rate of 2.9% in 2024.

3. Analysis of Sino-U.S. Strategic Competition

The primary cause of strategic competition between great powers lies in the distribution of core interests. The geopolitical and strategic economic relations between China and the United States have undergone significant transformations, making comprehensive strategic competition an inevitable outcome.

3.1. The Impact of U.S. Reindustrialization Policy on Sino-U.S. Relations

Before the 2008 financial crisis, China and the United States were the leading nations in industrial capital and financial capital, respectively. China's rapid growth, despite its capital shortages, was largely driven by the long-term credit advantage of the Chinese government. The inherent demands of the government credit system required the integration of fiscal and financial policies, which, given China's capital scarcity, prevented the country from achieving a global expansion of financial capital. Objectively speaking, China's extensive industrialization and capital shortages formed an economically complementary relationship with the United States, which had an excess of financial capital.

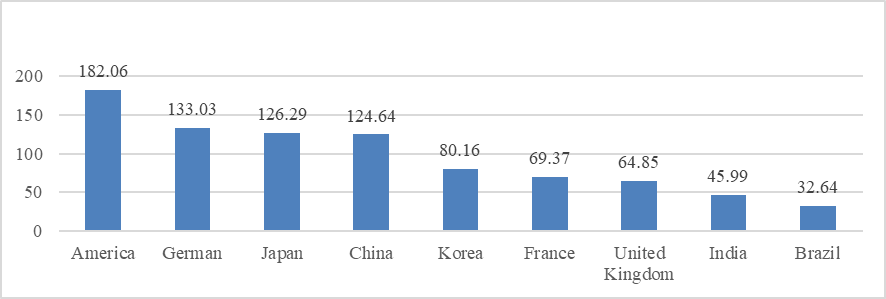

The financial crisis prompted the United States to adjust its economic strategy and pursue a "reindustrialization" agenda. This shift was characterized by several key measures. First, the U.S. initiated financial system innovations, signing multilateral currency swap agreements with major Western economies to mitigate the risks associated with short-term liquidity shortages. Second, the U.S. employed corresponding geopolitical strategies, such as creating regional conflicts and building anti-China alliances, to attract overseas capital back to the United States. Finally, the U.S. developed domestic shale gas and oil resources, significantly lowering crude oil prices. This price reduction led to substantial fiscal contractions in major oil-producing countries, reduced returns on energy sector investments, and triggered a large-scale capital return to the United States. The financial crisis of 2008 thus facilitated a rebalancing of U.S. industrial capital.[5] By 2023, the U.S. Manufacturing Power Index stood at 182.06, with the Industrial Production Index continuously rising, maintaining both absolute and relative advantages as the world's leading industrial power.[6]

Figure 1: 2023 Manufacturing Power Index of Nine Countries Worldwide

Source: 2023 Manufacturing Power Index

Simultaneously, China adjusted its economic strategy by promoting the commercialization and public listing of banks, advancing the monetization and capitalization of the domestic economy. Additionally, the central bank's large-scale monetary injections and quantitative easing resulted in China's M2/GDP ratio exceeding 180% for an extended period. Consequently, China entered an era of relative financial capital surplus.

Figure 2: China's M2/GDP Ratio Trend

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China and the People's Bank of China

In recent years, China has actively pursued the "going global" strategy for financial capital and real industries, as well as the "Belt and Road Initiative," promoting the internationalization of the renminbi. As China transitioned from industrial capital to financial capital, strategic interests between China and the United States began to clash, with China encroaching on the global interests of U.S. financial capital. The rebalancing of the U.S. real economy and the expansion of Chinese industrial capital have created a competitive dynamic. China's large-scale overseas investments have compressed the profit margins of U.S. capital, leading to a shift in Sino-U.S. strategic interests from an economically complementary relationship to an economically antagonistic one, a shift that has manifested in the "comprehensive decoupling" of China and the United States.

3.2. Trade War and the Dual Transfer of Costs

In the context of global competition, countries objectively occupy three distinct positions—core, semi-core, and peripheral—forming a "core-semi-core-peripheral" dependency structure. Through unequal exchange and systemic exploitation, the interests of semi-peripheral and peripheral regions are disproportionately transferred to the core countries, which in turn reinforces the position of core countries while weakening the status of peripheral nations.[7]

In this global competitive landscape, countries experience varying levels of gains and losses. The first category consists of core nations that dominate financial capital; these countries can achieve a "winner-takes-all" scenario and pay minimal costs. The second category includes semi-core countries that align with the core nation's institutional system and, as strategic partners, can "piggyback" on the core nation's gains. When their strategic interests align closely with the core nation's, they can share in the core nation's benefits. The third category is composed of peripheral nations, whose economies are primarily resource-based or focused on the real economy. These nations often bear the transferred institutional costs, frequently finding themselves in a state of exploitation without realizing it. The United States belongs to the first category, while China is classified as a peripheral nation.

Currently, the financial hegemony of the core nations, particularly the United States, is increasingly taking on fascist tendencies, representing the greatest threat to contemporary human society. This is because the excessive debt of core nations requires the use of "hard power," "soft power," and "smart power" to externalize and transfer these costs, even at the risk of initiating wars. In the new phase of global financial capitalism, the United States occupies the top position in the "current account deficit + capital account surplus = profitable capital export" equation, allowing it to simultaneously issue more currency and debt, which inevitably leads to the issuance of more currency to purchase this increased debt. Thus, the U.S. has become the largest financial economy driving the overexpansion of virtual capital in a two-dimensional manner. This has led to the rise of terms in American mainstream society that contradict basic market values, such as "negative credit."

Given these enormous gains, the United States is likely to actively adjust its monetary and geopolitical strategies to maintain its position in capturing institutional benefits. Furthermore, the U.S. has also pursued the restructuring of global systems and institutions to more easily transfer economic and political costs to other countries, thereby maximizing economic returns. Without these measures, the United States would struggle to maintain its economy, which is excessively bubble-driven and dominated by virtual capital, and its heavily indebted political system.

Economic cost transfer refers to the process by which core countries, through international monetary and financial institutions, dismantle the restrictions imposed by developing sovereign nations on the flow of financial capital, transferring the risks associated with financial globalization primarily to other countries to maximize their own gains.[8] As a result, the U.S. is likely to provoke structural contradictions within global financial capitalism, leading the global economy into a downward cycle.

Moreover, the structural inequality in wealth distribution under capitalism has led to growing dissatisfaction among the lower and middle classes, exacerbating ethnic, religious, and regional conflicts, and resulting in social unrest. Almost all governments, regardless of their system, are inevitably confronted with multiple layers of economic, social, and political instability. However, the instability of non-core countries presents the U.S. with opportunities for low-cost intervention, using various forms of soft power—such as ideologically driven education, culture, academic research, legal services, and standard-setting—and smart power, which involves instigating political, religious, ethnic, and geopolitical conflicts to induce the people of non-core countries to accept American political and cultural influence, redirecting their struggles against their own domestic systems.

Indeed, the high political and social system costs in the United States necessitate substantial economic returns to maintain its stability. However, the international order and organizations established by the United States and other Western countries after World War II have not developed effective mechanisms to counter a unipolar hegemonic state and lack experience in global governance. Consequently, the United States is able to transfer its "political costs," primarily through its monetary-geopolitical military strategy, along with various soft power and smart power tactics, to destabilize countries it views as obstructing its strategic interests.

The benefits of transferring political costs are particularly significant. Political and economic instability in competitor or non-core countries allows the United States to acquire valuable assets during crises and attract international capital back to its own economy. Additionally, destabilizing non-core countries under the guise of "liberal democracy" undermines these countries' ability to regulate their economies and control capital. When a nation's capital is not yet competitive, the U.S. can suppress relatively competitive national capital, stifling its long-term international competitiveness. Although China is a peripheral nation, it is perceived by the United States as one of the countries obstructing its strategic interests. Through the trade war, the United States has sought to suppress China's real economy, destabilize its economic environment, and implement related monetary and geopolitical strategies to encourage the return of some industries to the U.S., thereby reaping the benefits of the "dual cost" transfer.

3.3. Ideological Construction of the New Cold War

As the "China Threat Theory" emerged, the United States initiated a new Cold War era, replacing the post-Cold War period. During this time, the world was undergoing a major transformation in globalization, and while China seized the opportunity to benefit, it also paid a significant cost through "dual outputs." In 2001, due to the "IT bubble burst" that led to the "new economic crisis" and the "9/11 attacks," the United States failed to promptly address the "China Threat Theory."

Faced with the challenges of dual economic and political crises, the United States shifted its strategic focus to West Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa. Although this shift created vast market opportunities for the U.S. military-industrial complex, it also led to a large-scale transfer of U.S. manufacturing industries to China. This transfer brought substantial economic benefits to China. On one hand, China, previously in a state of deflationary crisis, attracted significant foreign investment, making it the world's top destination for foreign direct investment by 2020. On the other hand, China, having just joined the WTO, was rapidly integrated into the globalized economy. By 2020, China had become the world's largest trader by volume and had the largest trade surplus. Additionally, China maintained double-digit economic growth for over a decade, enabling it to assert political legitimacy through economic achievements, which were strongly validated in practice.

While China's economy was experiencing rapid growth, the United States faced the "subprime mortgage crisis" in 2007 and the "Wall Street financial meltdown" in 2008, which allowed China roughly 12 years to develop its real economy and reform its monetary system. By 2020, both U.S. political parties had reached a strong consensus on the China issue. As China established and maintained its new socialist market economy system, the U.S. strategy to contain China had clearly failed. Both U.S. parties concluded that the only viable approach was to reconstruct a "Cold War" and develop a new Cold War ideology that positioned China as the enemy, thereby reestablishing a "one world, two systems" global order. Consequently, the United States began promoting a "de-Chinaization" movement within the Western world, aiming for a "hard decoupling" between the West and China. In essence, the "America First" political strategy of the new Cold War has dictated the U.S. economic policy towards China. To this day, the Biden administration continues the China policy initiated during the Trump era, indicating that the U.S. has committed to a hardline stance against China, inevitably dragging China into a comprehensive "new Cold War" and fully opposing China's rise.

4. China's Strategic Response

Objectively, the geopolitical and economic relations between China and the United States have shifted from complementarity to mutual exclusivity, with both sides now exhibiting antagonistic contradictions. This shift has introduced new challenges, as the United States seeks to externalize the costs of Sino-U.S. conflicts and its internal crises onto other countries. China, in turn, must confront the challenges posed by U.S. financial expansion and the repatriation of industries. As the passive party in this dynamic, China not only needs to adjust its strategy towards the U.S. but also must recognize the rationale behind actively and directly confronting these challenges.

In the short term, China needs to prioritize comprehensive national security by vigorously promoting rural revitalization and thoroughly adjusting its internal strategies. This involves significantly enhancing the organization of rural societies, utilizing their "internalization of externalities" crisis absorption mechanisms to mitigate risks and achieve a soft landing in crises, thereby establishing a foundational security base for the nation.

First, China should reasonably rely on large-scale national investments to maintain economic growth by increasing the scale of tangible assets and accelerating the monetization of the economy through political credit. Simultaneously, efforts should be made to ensure the effective appreciation of tangible and financial assets, while maintaining reasonable control over government debt and the ratio of non-performing bank assets.

Second, by leveraging the advantages of the rural revitalization strategy and the comparative strength of concentrating resources, China should fully utilize the guiding role of national political investment to drive governance innovation at the grassroots level in rural areas. This would enhance the organization of rural societies, promote the revival of ecological civilization, and innovate in the governance of rural culture, thereby activating the "internalization of externalities" mechanism within rural societies.

Finally, China should establish a global narrative framework for its "going out" strategy, critically reflecting on the substantial costs of merely emphasizing the external expansion of industrial and financial capital. This approach not only aids in researching national security strategies but also contributes to risk management for China's overseas expansion.

5. Conclusion

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly impacted the international political and economic landscape, temporarily easing Sino-U.S. strategic competition in the short term, but its negative effects have rippled across the globe. Against the backdrop of a global economic downturn, China has begun to construct a new development pattern centered on domestic circulation, which is mutually reinforced by international circulation.[9] Meanwhile, the United States has sought to alleviate fiscal pressures, stimulate the domestic economy, reduce inflation, and ease social tensions by issuing more Treasury bonds.

In the long term, strategic competition between the two nations is likely to become the "new normal." First, China's economic growth rate significantly outpaces that of the United States, and China is projected to surpass the U.S. by 2030 to become the world's largest economy.[10] Second, the pandemic has exacerbated social divisions within the United States, leading to increased social unrest and a slowdown in societal development. Rising unemployment and the uncontrolled spread of the virus have hindered the full recovery of production in the U.S., and domestic political movements have further eroded the country's political capacity. Finally, China's outstanding performance in pandemic control and the aggressive expansion of its overseas strategies have heightened American concerns. In summary, with China's soft and hard power continuing to rise, Sino-U.S. strategic competition is likely to intensify, potentially leading to "hard decoupling" and even localized conflicts.

References

[1]. Ye, S. L., & Liu, X. F. (2015). "Super third party": Japan's perception of the construction of a new type of major power relationship between China and the United States. Northeast Asia Forum, (12).

[2]. Xia, L. P. (2024). U.S. institutional balancing against China under the national security strategy and its impact. Asia-Pacific Security and Maritime Studies, (3).

[3]. Ministry of Commerce. (2019). Statement by the spokesperson of the Ministry of Commerce on the U.S. announcement to further increase tariffs on Chinese goods exported to the U.S. [EB/OL]. Retrieved from http://www.mofcom.gov.cn/article/ae/ag/201908/20190802893477.shtml

[4]. Wen, T. J., & Gao, J. (2015). China's "dual output" pattern to the U.S. and its new changes. Economic Theory and Business Management, (7).

[5]. Li, S. K. (2010). The impact of the financial crisis on the U.S. banking industry: A review and prospect. International Finance Research, (12).

[6]. Manufacturing Power Index 2023 [EB/OL]. Retrieved from https://www.sohu.com/a/363793094_478183

[7]. Wallerstein, I. (2004). World-systems analysis. Duke University Press.

[8]. Wen, T. J. (2021). Globalization and national competition. Oriental Publishing.

[9]. Wen, T. J., & Gao, J. (2015). China's "dual output" pattern to the U.S. and its new changes. Economic Theory and Business Management, (7).

[10]. Zhang, C., & Zhao, Z. R. (2021). The China-U.S. trade war in the "post-pandemic" era: Causes, trends, and responses. Regional and Global Development, (01).

Cite this article

Lu,X. (2024). Analysis of Strategic Competition Between China and the United States in the New Cold War Era. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,124,219-226.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Economic Management and Green Development

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Ye, S. L., & Liu, X. F. (2015). "Super third party": Japan's perception of the construction of a new type of major power relationship between China and the United States. Northeast Asia Forum, (12).

[2]. Xia, L. P. (2024). U.S. institutional balancing against China under the national security strategy and its impact. Asia-Pacific Security and Maritime Studies, (3).

[3]. Ministry of Commerce. (2019). Statement by the spokesperson of the Ministry of Commerce on the U.S. announcement to further increase tariffs on Chinese goods exported to the U.S. [EB/OL]. Retrieved from http://www.mofcom.gov.cn/article/ae/ag/201908/20190802893477.shtml

[4]. Wen, T. J., & Gao, J. (2015). China's "dual output" pattern to the U.S. and its new changes. Economic Theory and Business Management, (7).

[5]. Li, S. K. (2010). The impact of the financial crisis on the U.S. banking industry: A review and prospect. International Finance Research, (12).

[6]. Manufacturing Power Index 2023 [EB/OL]. Retrieved from https://www.sohu.com/a/363793094_478183

[7]. Wallerstein, I. (2004). World-systems analysis. Duke University Press.

[8]. Wen, T. J. (2021). Globalization and national competition. Oriental Publishing.

[9]. Wen, T. J., & Gao, J. (2015). China's "dual output" pattern to the U.S. and its new changes. Economic Theory and Business Management, (7).

[10]. Zhang, C., & Zhao, Z. R. (2021). The China-U.S. trade war in the "post-pandemic" era: Causes, trends, and responses. Regional and Global Development, (01).