1. Introduction

The traditional equity structure is characterized by "one share, one vote," where shareholders have voting rights proportional to the number of shares they hold. To better protect certain key shareholders, such as the intellectual capital of the company’s founders, and to ensure that founders or senior management retain control of the company, the dual-class share structure was introduced. In a dual-class share structure, shares are typically divided into high and low voting rights categories, allowing shareholders with high-voting shares to retain greater decision-making power while still distributing profits equally.

The dual-class share structure originated with International Silver in 1898, where some key shareholders issued non-voting and preferred stock. This new stock issuance transferred voting rights from many small shareholders, giving the founders absolute control. Subsequently, many companies adopted this structure for various reasons, including protection against hostile takeovers. Lease, McConnell, and Mikkelson studied 26 companies that issued two types of common stock, hypothesizing that different shares confer different voting rights to their owners and that holders of high-voting common stock might gain incremental benefits [1].

After 2000, tech-based internet companies like Google, which adopted dual-class share structures, proliferated. By 2015, approximately 8% of publicly listed companies in the U.S. employed a dual-class share structure. While this structure helps maintain control for founders and executives, it has also caused problems. For example, Snap's dual-class share structure at its 2017 IPO resulted in centralized power, with founders making decisions with little oversight from shareholders, indirectly contributing to a decline in stock price and market share.

As the times have progressed, China's capital market has seen several advanced companies abandon the traditional "one share, one vote" system and look abroad to reform their equity governance mechanisms. Internet giants like Baidu have listed in the U.S. with dual-class share structures. Recognizing the necessity of dual-class share structures for promoting rapid and high-quality development and ensuring smooth capital financing, China has introduced new exchange policies to reduce restrictions on the listing of companies with dual-class share structures. On April 24, 2018, the Hong Kong Stock Exchange introduced new IPO regulations allowing companies with dual-class share structures to list. Subsequently, many companies, such as Alibaba, which were already listed in the U.S., completed secondary listings in Hong Kong. Technology companies such as Xiaomi, Meituan, and Kingsoft Cloud have also listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange with dual-class share structures. On June 13, 2019, the STAR Market was officially launched, permitting companies with dual-class share structures to list. UCloud was among the first to adopt this structure, successfully listing on the STAR Market in 2020, symbolizing the formal adoption of the new equity structure in China’s A-share market.

NIO, as the world’s first automaker to list in New York, Hong Kong, and Singapore, has also adopted a dual-class share governance structure. This paper will analyze NIO’s corporate governance practices to explore the implementation details and potential issues of dual-class share structures in technology enterprises. For industries and external environments that are constantly evolving, it is crucial for technology companies to adopt appropriate corporate governance mechanisms to maintain efficient operations.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Review of Literature on Corporate Governance

Research on corporate governance originates from Jensen and Meckling, who primarily discussed the agency conflict between shareholders and managers [2]. They categorized shareholders into internal and external shareholders, arguing that a company’s value increases with the proportion of internal shareholding. Subsequently, Shleifer and Vishny suggested that the presence of a major shareholder can solve the problem of internal control within a company, which occurs when managers are unsupervised due to dispersed ownership [3]. They also highlighted the conflict of interest between major and minor shareholders, noting that a concentrated ownership structure might lead to the expropriation of minor shareholders by controlling shareholders. Some literature further suggests that there is a dual governance relationship and agency conflict among management, major shareholders, and minority shareholders, requiring a balance between the supervision effect and expropriation effect of major shareholders.

To better protect the interests of all parties, some scholars have studied the relationship between equity structure, company performance, and value. Ma, YL et al. analyzed data from listed companies over a ten-year period, finding that the degree of equity balance, board size, and executive incentives all positively influence company performance [4]. Some recent studies indicate that technology enterprises face issues in corporate governance, such as unclear equity structures and inadequate recognition and definition of the value of specific human capital.

2.2. Review of Literature on Dual-Class Share Structures

The dual-class share structure was first proposed by Lease, McConnell, and Mikkelson, and significant research in this field has followed. Dimitrov, V., and Jain, P.C. studied a sample of 178 companies that switched from a "one share, one vote" system to a dual-class structure between 1979 and 1989, finding that adopting a dual-class share structure moderately increased company value and stock returns [1, 5]. Yang noted that R&D activities positively influence the valuation of companies with dual-class share structures but also pointed out that investor aversion to such companies may intensify due to R&D investments [6]. Smart S.B. and Zutter C.J. found that companies with dual-class share structures had lower stock discount rates compared to those with a "one share, one vote" system, arguing that the dual-class structure protects private control benefits [7].

However, some scholars argue that the dual-class share structure may increase agency costs and hinder company development. Sanford J. Grossman and Oliver D. Hart believed that the higher the voting rights held by the actual controllers of a company, the lower the shareholders' voice, making it more difficult to protect shareholder rights [8]. Reddy suggested that in the context of UK regulation, for high-growth technology companies, the risks associated with dual-class share structures might be mitigated through prudent control [9]. A specific type of sunset clause could be employed to strike a proper balance between resolving agency issues and providing effective incentives for controllers of dual-class share companies to increase company value in the long term. Such rules might be applicable to high-tech and innovative startups.

3. Analysis of the NIO Case

3.1. Basic Structure of the Dual-Class Share System

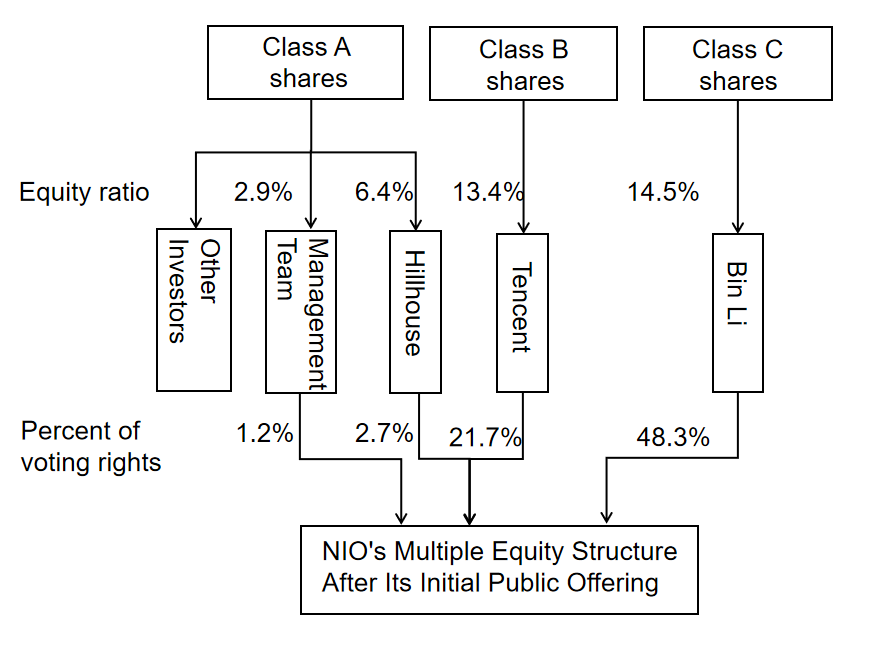

Unlike most companies that implement a dual-class share structure, NIO adopts an ABC three-tier share structure. At its initial listing in New York, NIO's shares were divided into three categories: Class A, Class B, and Class C. Class A shares correspond to one vote per share, Class B shares to four votes per share, and Class C shares to eight votes per share. Although the voting rights differ among the three classes of shares, the cash flow rights remain the same. Class B and Class C shares can be converted into Class A shares at any time at the discretion of the holder. However, Class A shares cannot be converted into Class B or Class C shares. Additionally, when Class B or Class C shares are transferred to another party, they automatically convert into Class A shares.

Table 1: shows the equity structure and voting rights ratio before and after the first listing.

Shareholder | Pre-IPO (Original) Shareholding Percentage | Post-IPO Shareholding Percentage | Voting Rights Percentage | Share Class |

William Li | 17.2% | 14.5% | 48.3% | Class C |

Tencent | 15.2% | 13.4% | 21.7% | Class B |

Hillhouse Capital | 7.5% | 6.4% | 2.7% | Class A |

Data Source: NIO Inc. Initial Public Offering Prospectus, September 2018

William Li is the largest controlling shareholder, holding all of the Class C shares, which gives him 48.3% of the voting rights after the listing, despite owning only 14.5% of the shares. Other founding team members, excluding William Li, hold Class A shares with a combined ownership of 2.9% and a total of 1.2% of the voting rights. Therefore, the founding team collectively holds 49.5% of the voting rights. Tencent Holdings owns all of the Class B shares, controlling 21.7% of the voting rights with a 13.4% ownership stake.

Before the company went public, the founder William Li owned only 17.2% of the equity and was unable to exert control over NIO Inc. However, by adopting a dual-class share structure for the IPO, William Li gained nearly half of the company's control with a smaller equity stake. With some external shareholders relinquishing involvement in corporate governance and the dispersion of equity, William Li and the founding team can make decisions on most of the company’s matters, reducing excessive interference from external investors and ensuring the implementation of strategic decisions.

Figure 1: Major Shareholder Structure After the First IPO.

Considering market conditions and financing costs, NIO conducted a second and third listing. The second listing was an introduction on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKEX), which did not involve the issuance of new shares. After this listing, Li Bin's shareholding decreased to 10.6%, with a voting power of 39.0%. Subsequently, after Tencent converted some of its Class B shares into Class A shares, Li Bin's proportion of Class A shares became 9.9%, and his total voting power increased to 44.5%. Tencent's shareholding was 9.8%, and its voting power decreased from 17.4% to 5.6%. The third listing was also an introduction on the Singapore Exchange (SGX), which similarly did not involve the issuance of new shares. Since this listing occurred shortly after the second, there were no significant changes in the share structure.

3.2. Multi-Class Share Structure and Board Member Arrangements

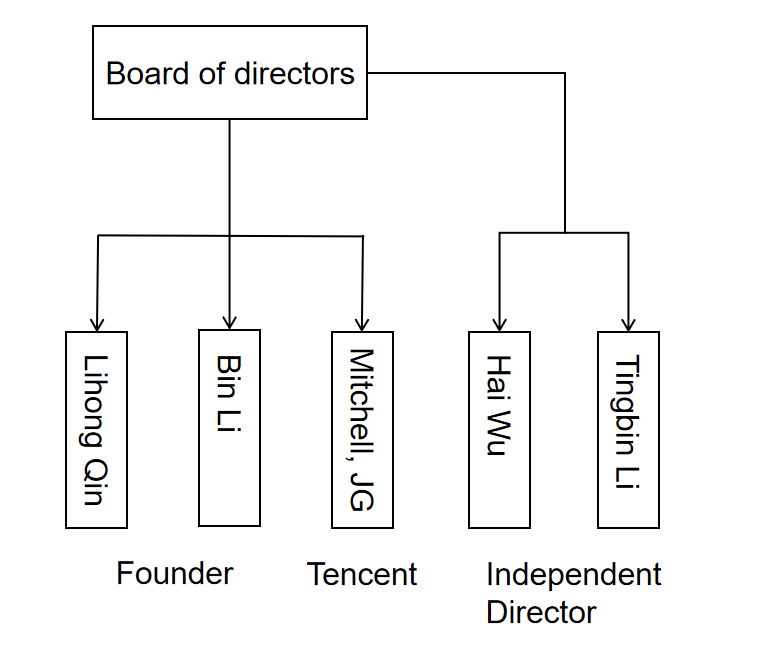

Through these three listings, although Li Bin held Class C shares and obtained super voting rights, his voting power remained below 50%, falling short of absolute control. This is also less than other companies with dual-class share structures, such as Snap, where the founder holds 89% of the voting rights. However, Li Bin further strengthened his control over the company through board member arrangements.

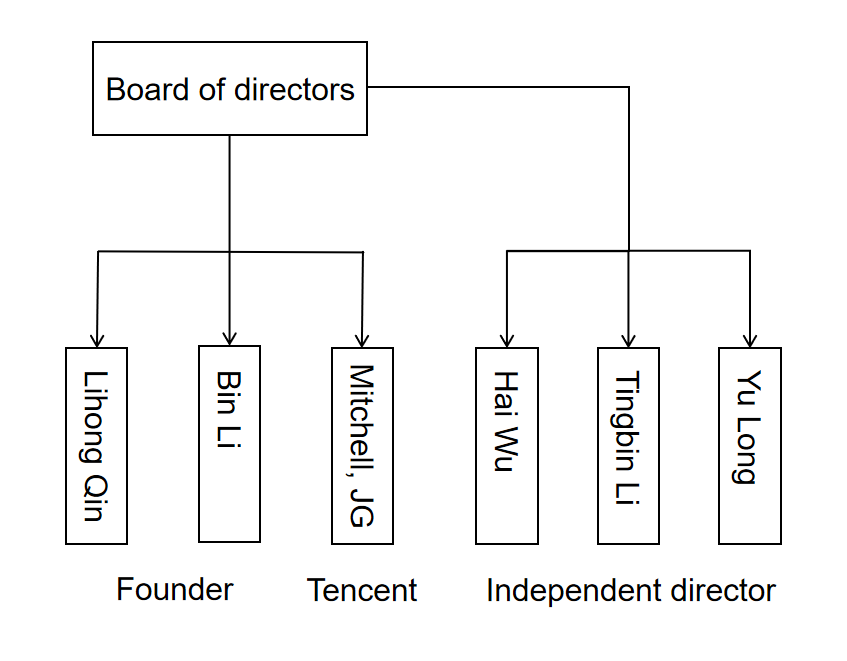

NIO's annual report shows that when the company first listed on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), the board consisted of five directors, including Li Bin, with two of them being independent directors. Among the two executive directors, one was appointed by Tencent, and the other was co-founder Qin Lihong. In most cases, Li Bin and the co-founder had absolute control over the board. On July 21, 2021, prior to the second listing on the HKEX, an additional independent director, Long Yu, was added to the board. Long Yu succeeded Li Bin as the board's nomination committee member and established an independent corporate governance committee, consisting solely of Long Yu, to oversee the independent investigation related to the allegations in the short-selling report.

Figure 2: Board Structure at the Time of Initial IPO.

Figure 3: Board Structure at the Time of the Second Listing.

3.3. Business Performance Under the Multi-Class Share Structure

3.3.1. Company Financial Situation

Since its listing, the company has been in a "cash-burning" phase, with net profits consistently in the negative. After its 2018 IPO on the New York Stock Exchange, the net profits for 2018 and 2019 were -23.328 billion yuan and -11.413 billion yuan, respectively. In early 2020, under significant financial pressure, NIO reached a strategic cooperation with Hefei State-owned Assets, successfully navigating through its most perilous phase. The stock price began to gradually recover in May, reaching an all-time high of $66.99 per share in January 2021. However, despite the strong stock performance, high R&D expenditures and market conditions led to continued poor net profitability. The annual net profits for 2020, 2021, 2022, and 2023 were -5.611 billion yuan, -10.572 billion yuan, -14.559 billion yuan, and -21.147 billion yuan, respectively. After the declining losses from 2018 to 2020, the losses exceeded 10 billion yuan again in 2021 and continued to increase annually, leaving the company still some distance from achieving positive profitability. Regarding its main business, the total deliveries for 2023 grew by 30.7% year-on-year, indicating that its brand premium was recognized by consumers. However, affected by price wars, the increase in sales was also accompanied by a decrease in gross margin. Additionally, NIO’s average selling price per vehicle has decreased, and while maintaining a high gross margin, it must also focus on preserving its high-end brand image.

3.3.2. Management Situation

Since the company's listing, Li Bin has focused on building the management team and enhancing the company’s operational capabilities through a robust management structure. On one hand, several senior executives left NIO from the second half of 2019 to the first half of 2020, during which time three Executive Vice Presidents, two Senior Vice Presidents, two Vice Presidents, and three Assistant Vice Presidents were promoted. At the end of September 2019, the former CFO and Vice President of Finance resigned, and NIO quickly appointed the experienced Feng Wei as the new CFO. Following Feng Wei’s appointment, NIO’s financial situation improved, securing nearly $500 million in convertible debt financing and an initial 7 billion yuan investment from the Hefei government in early 2020. Additionally, six major banks provided credit lines, alleviating the company’s cash flow constraints. In the second quarter of 2020, the company achieved positive gross margin and free cash flow. On the other hand, after the retirement of co-founder and Executive Vice President Zheng Xiancong, Li Bin promoted three new Executive Vice Presidents to oversee product and project management, quality management, and research and digitalization. One of these executives managed the business development department that was split off from the digital intelligence sector in 2018. NIO frequently adopts this approach of splitting departments when key personnel leave and replacements are lacking, to maintain business stability and continuity and ensure the effective execution of departmental functions.

3.3.3. Financing Situation

NIO’s financing has primarily been accomplished through equity financing. The Hefei government invested 7 billion yuan to acquire a 24.1% stake in NIO and signed a 120 billion yuan performance agreement, setting revenue targets, new model releases, and a requirement to list on the STAR Market by 2025. Based on current information, NIO may need to repurchase this investment at an annual interest rate of 8.5%. In July and December 2023, NIO secured two rounds of investments totaling approximately $3.3 billion from Middle Eastern investor CYVN Holdings, providing support for NIO’s subsequent operations and innovation. After these two rounds of investment, CYVN holds approximately 20.1% of NIO’s shares. In June 2024, due to its outstanding achievements in the charging and battery swapping sectors, NIO attracted another round of state capital, receiving a new 1.5 billion yuan investment from Wuhan Guangchuang Fund to support the development of energy replenishment technology.

4. Analysis of Dual-Class Share Structure from the Perspective of Corporate Governance

4.1. The Highly Controversial Governance Framework of Dual-Class Share Structures

Dual-class share structures, as an innovative form of corporate governance, have garnered widespread external attention. As seen in the case of NIO, the super voting rights effectively ensured the authority of William Li and his founding team. Despite long-term negative net profits and frequent management changes, the company's operations remained stable, consistently securing new financing and launching new products. However, not all companies with dual-class share structures are as stable, and some scholars have raised concerns. Zhang Lina argued that while such a share structure can mitigate the dilution effect of equity financing on control rights, enhance company value, and better incentivize founders and their management teams, it also weakens the protection of basic investor rights and increases agency costs due to the mismatch between voting rights and cash flow rights [10]. The Financial Times pointed out at the time of Snap's IPO that, by any standard, Snap's governance arrangement was flawed, with its board bearing minimal responsibility. The changes in voting and ownership structures significantly reduced the management's accountability to shareholders. As corporate governance continues to evolve and improve, boards have become more professional, and the ranks of activist shareholders are growing, all of which contribute to the refinement of dual-class share structures.

4.2. Sunset Clauses in Dual-Class Share Structures

The debate over whether dual-class share structures enhance or diminish company value remains unresolved, and empirical research has yet to provide conclusive evidence of their impact. Jill E. Fisch noted that calls for regulators or stock exchanges to completely ban dual-class shares have not succeeded [11]. As a result, some researchers have proposed a middle ground, allowing companies to go public with dual-class share structures but requiring such companies to implement mandatory time-based "sunset clauses." These clauses typically stipulate that, under certain conditions, differentiated voting rights should revert to a one-share-one-vote system. For example, when NIO was listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange for the second time, part of the Class B shares held by Tencent were converted to Class A shares, reducing Tencent's shareholding, while William Li held the converted Class A shares, thereby strengthening his control over the company. The social gaming company Zynga faced significant controversy over its 70:1 dual-class share structure. After its founder, Mark Pincus, stepped down as CEO, the sunset clause triggered, converting the company to a single-class share structure. Following the announcement, Zynga's stock price rose by 1.4%. Cai Leijie pointed out that sunset clauses are an effective means of regulating dual-class share structures [12].

Since the practice is still in its early stages, sunset clauses in the charters of listed companies in China exhibit serious content homogeneity and unreasonable conditions. This includes issues such as determining the appropriate length of the fixed-term sunset clause and regulating opportunistic behavior by super voting right holders. Anita Anand argued that the law should mandate fixed-term sunset clauses to prevent the continued existence of dual-class share structures after their initial rationale has expired [13]. At the level of corporate governance, Snap's governance structure, due to the lack of public shareholder voting rights supervision and the absence of a sunset clause, may gradually increase its agency costs, leading to lower governance efficiency. However, Jill E. Fisch Spointed out that mandatory fixed-term sunset clauses do not resolve the issues associated with dual-class share structures and have drawbacks, such as arbitrary term selection, moral hazard, and the public shareholders' tendency to terminate dual-class share structures [11].

5. Conclusion

This paper focuses on the unique dual-class share structure of technology-based companies, using NIO, which adopts an ABC dual-class share structure, as a case study. It explores the corporate governance structure since NIO's IPO and concludes that the company's operations have remained stable under this governance structure. NIO not only has a well-structured board of directors and management organization but also maintains market share for both new and established, well-known products, ensuring stable cash flow for this capital-intensive, emerging technology company. With diverse financing channels, although the company is still in a loss-making phase, trends in business sales and other areas appear positive.

We also observed ongoing controversies surrounding dual-class share structures. While many scholars believe that such structures can enhance corporate value, some scholars and media outlets argue that they lack stability, increase agency costs, and fail to resolve fundamental conflicts, thereby affecting governance efficiency. We have discussed these concerns in conjunction with sunset clauses, which can act as constraints on the governance structure.

Looking ahead, we believe it is crucial to closely monitor the evolving attitudes of stock exchanges and financial regulators toward this new governance structure, particularly regarding whether they recommend technology companies adopt dual-class share structures. Additionally, we suggest that companies using dual-class share structures should implement customized sunset clauses that better align with the current conditions of technology-based enterprises.

References

[1]. Ronald C.Lease, John J.Mcconnel and Wayne H.Mikkelson.The Market Value of Control in Publicly-traded Corporations[J].Journal of Financial Economics, 1983, 11(1):439-471.

[2]. Michael C.Jensen and William H.Meckling.Theory of the Firm:Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure[J].Journal of Financial Economics, 1976, 3:305-360.

[3]. Shleifer A and Vishny, RW.Large Shareholders and Corporate-Control[J].Journal of Political Economy, 1986, 94(3):461-488.

[4]. Yinlong Ma, Nur Syafiqah Binti A. Rahim, Siti Aisyah Bt Panatik and Ruirui Li.Corporate Governance, Technological Innovation, and Corporate Performance: Evidence from China[J].Heliyon 10, 2024, 10(11).

[5]. Valentin Dimitrov and Prem C.Jain.Recapitalization of One Class of Common Stock into Dual-class: Growth and Long-run Stock Returns[J].Journal of Corporate Finance, 2006, 12(2):342-366

[6]. Yang J, Liu W, Zhang X, et al. Influencing Factors of Dual Innovation in Manufacturing Companies[J]. Industrial Engineering and Innovation Management, 2023, 6(2): 63-70.

[7]. Smart S B, Zutter C J.Control as a Motivation for Underpricing:A Comparison of Dual and Single-class IPOs[J].Journal of Financial Economics, 2003, 69(1):85-110.

[8]. Sanford J.Grossman and Oliver D.Hart.One Share-one Vote and the Market for Corporate Control[J].Journal of Financial Economics , 1988, 20(1):175-202.

[9]. Bobby V.Reddy.Finding the British Google: Relaxing the Prohibition of Dual-class Stock from the Premium-tier of the London Stock Exchange[J].Cambridge Law Journal, 2020, 79(2):315-348.

[10]. Zhang, Lina. "Pros and Cons of Dual-Class Share Structures: A Case Study of Snap's IPO" [J]. Finance World, 2017, (16): 121-123.

[11]. Jill E.Fisch & Steven Davidoff Solomon.The Problem of Sunsets[J].Boston University Law Review, 2019, 99(3):1057-1094.

[12]. Cai, Leijie. "On the 'Sunset Clauses' in Dual-Class Share Structures" [D]. Beijing University of Chemical Technology, 2022. DOI:10.26939/d.cnki.gbhgu.2022.000359.

[13]. Anita Anand.Governance Complexities in Firms with Dual Class Shares[J].Annals of Corporate Governance, 2018, 3(3):184-275.

Cite this article

Sun,R. (2024). Analysis of Corporate Governance Structure in Technology Enterprises: A Case Study of NIO's Dual-Class Share Structure. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,126,32-39.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Economic Management and Green Development

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Ronald C.Lease, John J.Mcconnel and Wayne H.Mikkelson.The Market Value of Control in Publicly-traded Corporations[J].Journal of Financial Economics, 1983, 11(1):439-471.

[2]. Michael C.Jensen and William H.Meckling.Theory of the Firm:Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure[J].Journal of Financial Economics, 1976, 3:305-360.

[3]. Shleifer A and Vishny, RW.Large Shareholders and Corporate-Control[J].Journal of Political Economy, 1986, 94(3):461-488.

[4]. Yinlong Ma, Nur Syafiqah Binti A. Rahim, Siti Aisyah Bt Panatik and Ruirui Li.Corporate Governance, Technological Innovation, and Corporate Performance: Evidence from China[J].Heliyon 10, 2024, 10(11).

[5]. Valentin Dimitrov and Prem C.Jain.Recapitalization of One Class of Common Stock into Dual-class: Growth and Long-run Stock Returns[J].Journal of Corporate Finance, 2006, 12(2):342-366

[6]. Yang J, Liu W, Zhang X, et al. Influencing Factors of Dual Innovation in Manufacturing Companies[J]. Industrial Engineering and Innovation Management, 2023, 6(2): 63-70.

[7]. Smart S B, Zutter C J.Control as a Motivation for Underpricing:A Comparison of Dual and Single-class IPOs[J].Journal of Financial Economics, 2003, 69(1):85-110.

[8]. Sanford J.Grossman and Oliver D.Hart.One Share-one Vote and the Market for Corporate Control[J].Journal of Financial Economics , 1988, 20(1):175-202.

[9]. Bobby V.Reddy.Finding the British Google: Relaxing the Prohibition of Dual-class Stock from the Premium-tier of the London Stock Exchange[J].Cambridge Law Journal, 2020, 79(2):315-348.

[10]. Zhang, Lina. "Pros and Cons of Dual-Class Share Structures: A Case Study of Snap's IPO" [J]. Finance World, 2017, (16): 121-123.

[11]. Jill E.Fisch & Steven Davidoff Solomon.The Problem of Sunsets[J].Boston University Law Review, 2019, 99(3):1057-1094.

[12]. Cai, Leijie. "On the 'Sunset Clauses' in Dual-Class Share Structures" [D]. Beijing University of Chemical Technology, 2022. DOI:10.26939/d.cnki.gbhgu.2022.000359.

[13]. Anita Anand.Governance Complexities in Firms with Dual Class Shares[J].Annals of Corporate Governance, 2018, 3(3):184-275.