1. Introduction

China is gradually transitioning from a primary and secondary industry-based country to a tertiary industry-based country. Shanghai, a key financhial hub, exemplifies this transformation. However, during the COVID-19 epidemic, Shanghai people suffered from food shortages and panic[1], which undermined national confidence.

By comparing the number of permanent residents and GDP before and after the epidemic, the changes in consumers' consumption tendencies can be analyzed,, which in turn can be usedfor adjustments in government programs so that people can live and work in peace, harmony, blessings and happiness. In addition, consumer behavior is also a measure of how the world economy is rebounding after a huge blow, which is also an examination of the globalization of the world economy. The epidemic has developed different kinds of economic globalization. With the disruption of supply chains and the interdependence of countries in terms of critical resources, interconnectivity and interdependence between different regions and countries are becoming increasingly evident. This highlights the need for global cooperation and collaboration to address the challenges posed by the epidemic and its economic consequences.

2. Basic Information of Shanghai Finance

Shanghai is a commercial and financial center that covers a large area, with an advantage of human resources and is dominated by the tertiary industry.

Spanning an area of 6,340 square kilometers [2], Shanghai's strategic location at the mouth of the Yangtze River has made it a vital transportation hub and a bustling trading port.

Three major demands grew steadily. Fixed-asset investment grew by 5.2% year-on-year, while industrial investment, driven by major projects in the electronic information and automobile industries, grew by 17.7%, marking a decade-high record. Consumption patterns continued to be upgraded, with total retail sales of consumer goods reaching 1.27 trillion yuan, an 7.9% increase, and online shopping transactions exceeding 1 trillion yuan for the first time, reflecting a 29.7% surge. Foreign trade imports and exports grew steadily, totaling 3.4 trillion yuan, up 5.5 percent[3].

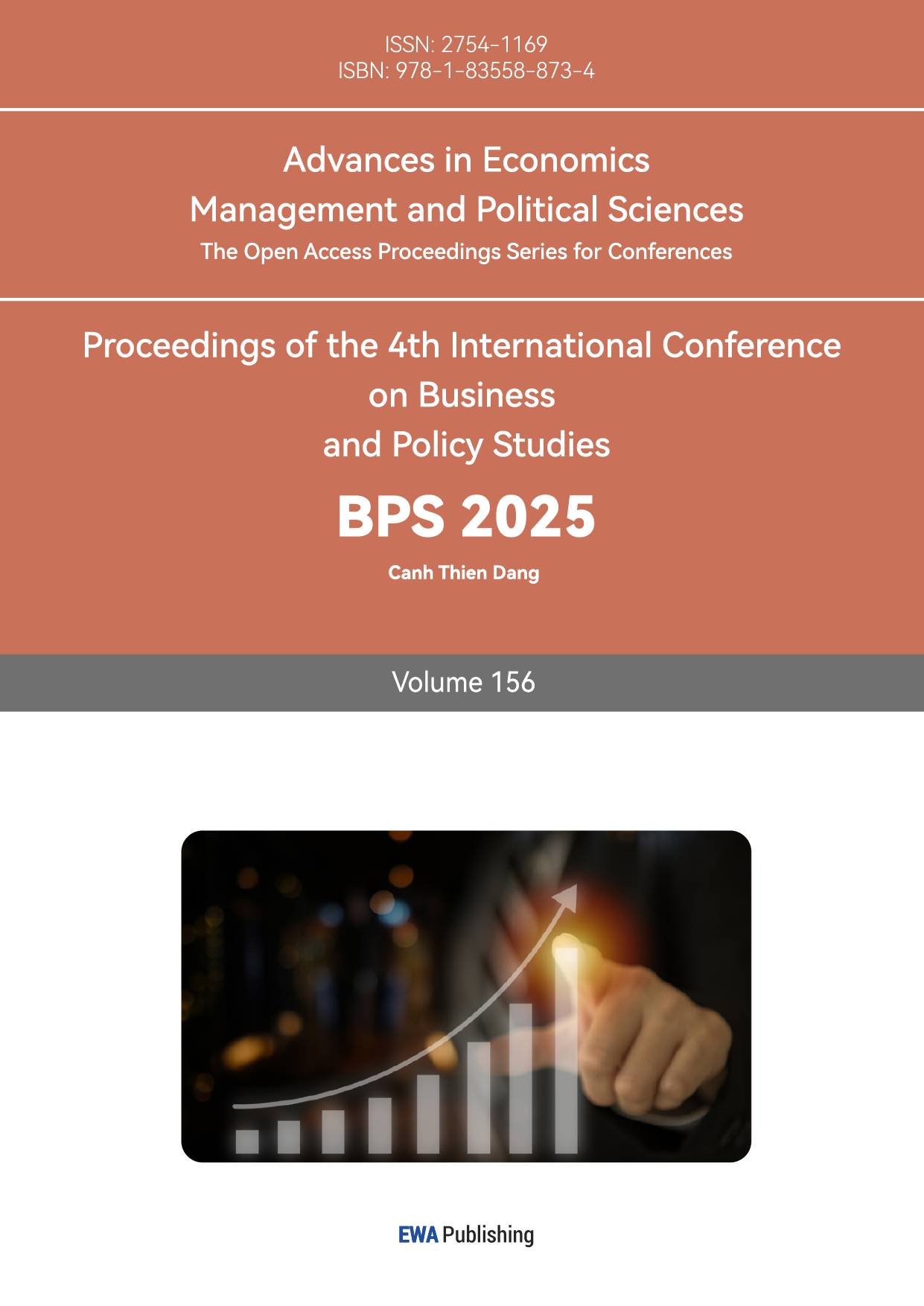

According to the data released by the Shanghai Statistics Bureau, Shanghai's gross regional product in 2021 was about 4.5 million million yuan, representing an 8.1% year-on-year growth at comparable prices. Among them, the added value of the tertiary industry exceeded 3 trillion yuan for the first time, amounting to about 300 billion yuan, with a year-on-year growth of 7.6%, accounting for 73.3% of GDP[4]. Notably, Shanghai's tertiary industry ranks second in the country in terms of contribution to GDP, solidifying its role as the primary driver of economic growth and a significant force propelling the city's economic development(Figure 1).

Figure 1: Changes in the tertiary industry of Shanghai's GDP over the past decade[5]

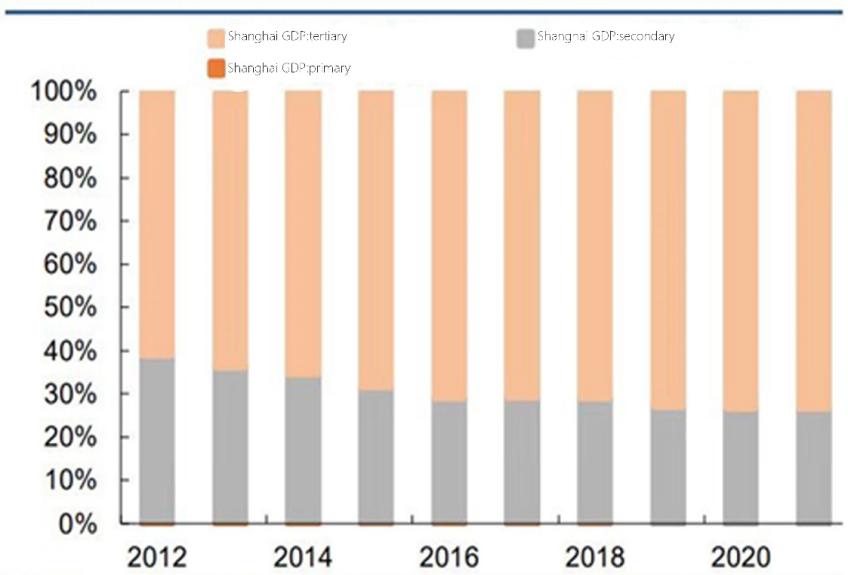

As the figure shows, in 2021, the financial industry, wholesale and retail trade, and real estate industry ranked as the top three contributors to GDP within Shanghai's tertiary sector[5].

The structural foundation of Shanghai's economy has undergone significant optimization over the decades. The primary industry has maintained a stable role, while the secondary industry has advanced its transformation and upgrading. Concurrently, the tertiary industry has witnessed rapid development, reshaping the composition of Shanghai's GDP. In 1952, the proportions of GDP attributed to the primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors were 50.5%, 20.8%, and 28.7%, respectively. By 2023, these proportions had shifted to 7.1%, 38.3%, and 54.6%, reflecting the transition from an economy dominated by the primary industry to one characterized by the synergistic development of all three sectors [6]. This balanced development has provided strong support for the sustained and healthy growth of the national economy.[6].

Figure 2: GDP Structure of Tertiary Industry in Shanghai, 2021[5]

Among these sectors, the financial industry has emerged as a crucial pillar of Shanghai’s economic growth, with its contribution to. Shanghai's unique geographical location and demographic advantages have cemented its status as China’s premier center for trade and commerce, as well as the nation’s hub for financial development(Figure 5).

3. Impact of the Epidemic on the Country

On March 28, 2020[7], China instituted a policy of sealing off major areas, including Shanghai. Given the lack of primary and secondary sector's development in Shanghai, food was basically transported from other cities. However, during the sealed off, Shanghai lost its source of food supply, which caused a shortage of resources during the epidemic. At the same time, the price of food in Shanghai increased significantly. Most people could not afford them, causing a decline in their living standards.. Additionally, the lockdown had profound economic consequences for Shanghai, particularly for its tertiary sector, which is a critical driver of the city's economy. With restrictions in place, consumer-facing industries such as restaurants suffered significant losses due to the absence of customers, causing widespread financial strain.

3.1. Psychological and Social Impacts

The Shanghai blockade marked a decisive shift in China's policy response to the outbreak. Although other cities followed Shanghai's lead in implementing stricter containment policies after the lifting of the blockade, local governments appeared to be overwhelmed by the implementation of these measures. In December, 2022, China relaxed its containment policies. In contrast to these two cities, public discontent following the Shanghai siege was more pronounced, and the rapid shift in policy was in part influenced by “pandemic fatigue”. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has highlighted “pandemic fatigue” as an important psychological effect during the COVID-19 pandemic, warning that this fatigue reduces people's motivation to comply with health-related policies [8].

People's negative feelings exacerbate the difficulty of weathering the epidemic. People panic about the never-ending nature of the epidemic and the decline of various industries, and consumers and workers worry about whether their standard of living will be lowered and health problems, and these negative sentiment lead to rebellion against the policy. This situation had made epidemic prevention and control more difficult.

Psychological distress during the lockdown also had broader social consequences. According to Jørgensen, pandemic fatigue is fuelled by a sense of loss of control and uncertainty exacerbated by severe uncertainty in the information environment and rapid changes in social norms[8]. This fatigue in turn fuels discontent, and anger is often directed not at the elusive virus but at political elites and intrusive COVID-19 control measures.

Psychological distress during the lockdown also had broader social consequences. Studies have shown that measures such as extended confinement can lead to higher rates of specific crimes, including domestic and intimate partner violence [9]. Risk factors such as unemployment, economic insecurity, and stress, exacerbated by the pandemic, contributed to this trend [10]. Conversely, restrictions on mobility reduced the likelihood of certain crimes, such as burglary and robbery, as people spent more time at home.

3.2. Economic and Financial Implications

The impact of investor reactions to pandemics on financial markets varies from country to country. It is important to recognize that the primary purpose of government action is to contain the virus, but its impact may extend to financial markets. The principles on which these measures are designed and the rigor with which they are implemented can lead to different market responses [12]. By assessing how countries' strategies for influencing social mobility and business activity indirectly affect investor expectations, the findings could provide useful insights for rethinking public policymaking.

Efforts to selectively isolate supply chains in key sectors intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic. This trend accelerated due to concerns about long-term geopolitical relations, Chinese policy preferences and regional security. China's share of total United States trade fluctuated significantly during the pandemic. [13].

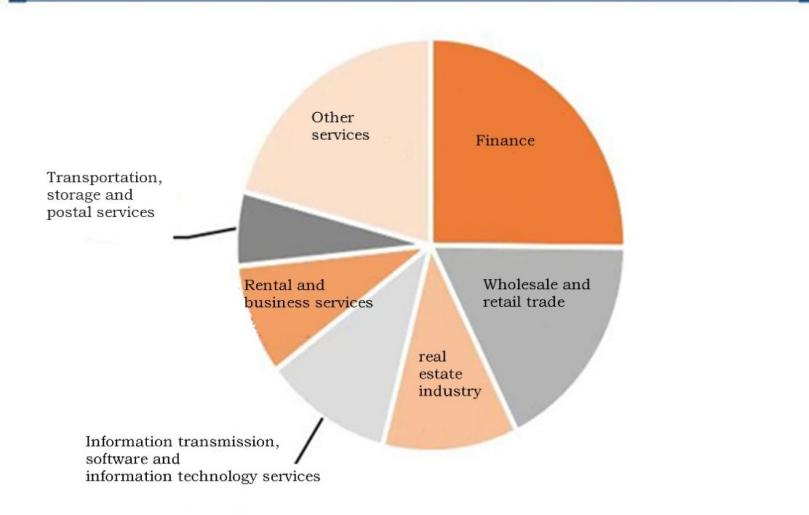

Figure 3: US-China energy supply chain bonded during COVID-19[13]

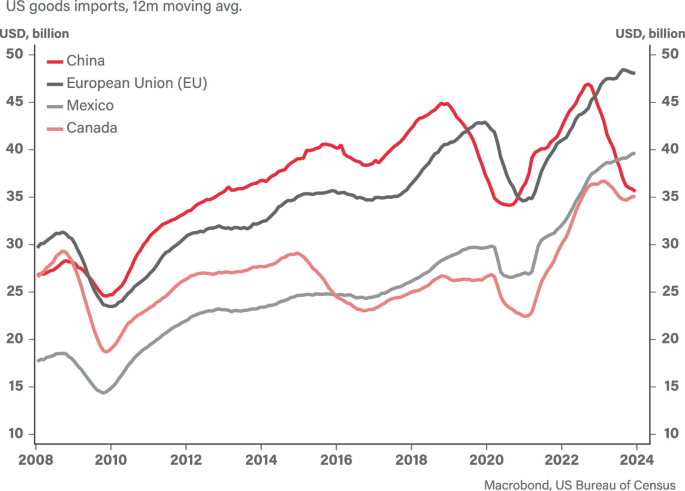

Bilateral trade between the US and China experienced a sharp decline in 2020 during the early stages of the Chinese embargo, but rebounded quickly as Chinese industrial production stabilises. Despite the high level of bilateral trade, China's share of total U.S. trade began to decrease from 2022 onwards due to supply chain disruptions caused by the stringent COVID-19 controls. By the end of 2023, China had fallen to the third largest source of U.S. imports for the first time since 2008, as shown in Figure 13. [13].(see i)n figure 13)

Figure 4: China fell to the third largest source of US imports[13]

Three factors contributed to the restructuring of bilateral supply chains during the COVID-19 pandemic. First, China's experience with pandemic-related socio-economic disruption convinced policymakers that improving supply chain self-sufficiency was a key national security priority. Second, the implementation of COVID-19 controls in China in 2022 caused significant disruption to global production, prompting investors to reassess China's role as a reliable centre for global supply chains. Third, escalating bilateral tensions and geopolitical concerns led the US to introduce a series of restrictive policies aimed at reducing supply chain dependence on China in key sectors.

In addition, foreign companies began to withdraw from the Shanghai market due to the pandemic, leading to an oversupply of labour. Concurrently, domestic companies reduced their workforces to manage variable costs during the recession, further exacerbating unemployment. This decline in employment, coupled with reduced income levels, led to a decrease in the standard of living and public satisfaction.

In addition, the epidemic first occurred in China, by affecting Chinese demand and supply, it first affected China's imports and exports. An outbreak abroad further affected China's foreign trade by affecting foreign demand and supply. Compared with the scenario without the epidemic, the epidemic would cause the annual growth rates of exports and imports to fall by 3.89 and 4.47 percentage points separately[14], respectively. In other words, the epidemic has dealt a huge blow to the Chinese economy by any measure.

In conclusion,COVID-19 not only affects people's reactions on a psychological level, which makes them irritable and irrational, but it also affects consumers on an economic level, reducing their consumption level and living standards. The interplay between two factors has contributed to the world's economic recession.

4. Conclusion

China is undergoing a major economic transition, shifting from reliance on the primary and secondary sectors to one that is increasingly dependent on the tertiary sector. Shanghai exemplifies this transition as a key hub for trade, finance, and commerce. However, However, the COVID-19 pandemic exposed vulnerabilities in this model. Shanghai's heavy reliance on external supplies, particularly for essential goods, left it unprepared during the lockdown, resulting in food shortages, heightened public panic, and weakened national confidence. The epidemic also underscored the complexities ofeconomic globalization, disrupting supply chains and increasing interdependence between regions and countries. This reveals the need for global cooperation to address the challenges posed by the epidemic and its economic consequences.

Additionally, the varied impact of pandemic-related investor reactions on financial markets emphasizes the role of government strategies in shaping market outcomes. Understanding how policy measures influence investor expectations can provide critical guidance for future decision-making.

China must adopt a critical perspective on the lessons learned from the pandemic, viewing it not only as a challenge but also as an opportunity to strengthen its economic resilience, enhance supply chain self-sufficiency, and foster global collaboration. By doing so, the country can better prepare for future crises and support sustainable economic growth.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to my seniors for many relevant papers for me to read and to my diligence and perseverance.

References

[1]. Renminwang, Notice to Pudong Residents, March 26, 2022, health.people.com.cn/n1/2022/0326/c14739-32384883.html

[2]. Zhao Jiaming, Shanghai Yearbook 2023, Zhao Jiaming, Jan 4, 2024. https://www.shtong.gov.cn/difangzhi-front/book/detailNew?oneId=2&bookId=344775&parentNodeId=344806&nodeId=641940&type=-1

[3]. Shanghai Headquarters, Shanghai Financial Operation Report (2019), July 19, 2019.http://shanghai.pbc.gov.cn/fzhshanghai/113589/3862478/index.html

[4]. Shanghai Statistics Bureau, Statistical Bulletin on National Economic and Social Development of Shanghai Municipality 2021, March 15, 2022.https://tjj.sh.gov.cn/tjgb/20220314/e0dcefec098c47a8b345c996081b5c94.html

[5]. Jiang Fei, Shanghai Economic Analysis Report - Macroeconomic Special Report, Nov 17, 2022.https://www.eeo.com.cn/2022/1117/567288.shtml

[6]. National Bureau of Statistics, Continuous optimization of economic structure and significant enhancement of development coordination - Report No. 8 of the series on the achievements of economic and social development in the 75 years of New China's history, Sep 14, 2024.https://www.gov.cn/lianbo/bumen/202409/content_6974986.htm

[7]. Shi Jiahui, This city is toughing it out through thick and thin.May 17, 2022.https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_18095021

[8]. Zhihang Liu, Jinlin Wu, Xinming Xia, Shifting sentiments: analyzing public reaction to COVID-19 containment policies in Wuhan and Shanghai through Weibo data, August 29, 2024.https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/s41599-024-03592-3

[9]. Abrams, D. S. (2021). COVID and crime: An early empirical look. Journal of Public Economics, 194, 104344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104344

[10]. Bradbury-Jones, C., & Isham, L. (2020). The pandemic paradox: The consequences of COVID-19 on domestic violence. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(13–14), 2047–2049. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15296

[11]. Lin, M. J. (2008). Does unemployment increase crime? Evidence from US data 1974–2000. Journal of Human Resources, 43(2), 413–436. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhr.2008.0022

[12]. Min Zhu, Shan Wen, Yupig Song, Impact of COVID-19 on jump occurrence in capital markets, June 24, 2024.https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/s41599-024-03357-y

[13]. Bo Zhengyuan, COVID-19: Catalyzing U.S.-China Supply Chain Realignments, JULY 30, 2024.https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-54766-9_4

[14]. China National Trade Administration (CNTA), Trading Economics, Sep 26, 2024.https://zh.tradingeconomics.com/china/exports

Cite this article

Dong,J. (2025). Impact of the COVID-19 Epidemic on China's Economy. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,156,67-72.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Business and Policy Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Renminwang, Notice to Pudong Residents, March 26, 2022, health.people.com.cn/n1/2022/0326/c14739-32384883.html

[2]. Zhao Jiaming, Shanghai Yearbook 2023, Zhao Jiaming, Jan 4, 2024. https://www.shtong.gov.cn/difangzhi-front/book/detailNew?oneId=2&bookId=344775&parentNodeId=344806&nodeId=641940&type=-1

[3]. Shanghai Headquarters, Shanghai Financial Operation Report (2019), July 19, 2019.http://shanghai.pbc.gov.cn/fzhshanghai/113589/3862478/index.html

[4]. Shanghai Statistics Bureau, Statistical Bulletin on National Economic and Social Development of Shanghai Municipality 2021, March 15, 2022.https://tjj.sh.gov.cn/tjgb/20220314/e0dcefec098c47a8b345c996081b5c94.html

[5]. Jiang Fei, Shanghai Economic Analysis Report - Macroeconomic Special Report, Nov 17, 2022.https://www.eeo.com.cn/2022/1117/567288.shtml

[6]. National Bureau of Statistics, Continuous optimization of economic structure and significant enhancement of development coordination - Report No. 8 of the series on the achievements of economic and social development in the 75 years of New China's history, Sep 14, 2024.https://www.gov.cn/lianbo/bumen/202409/content_6974986.htm

[7]. Shi Jiahui, This city is toughing it out through thick and thin.May 17, 2022.https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_18095021

[8]. Zhihang Liu, Jinlin Wu, Xinming Xia, Shifting sentiments: analyzing public reaction to COVID-19 containment policies in Wuhan and Shanghai through Weibo data, August 29, 2024.https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/s41599-024-03592-3

[9]. Abrams, D. S. (2021). COVID and crime: An early empirical look. Journal of Public Economics, 194, 104344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104344

[10]. Bradbury-Jones, C., & Isham, L. (2020). The pandemic paradox: The consequences of COVID-19 on domestic violence. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(13–14), 2047–2049. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15296

[11]. Lin, M. J. (2008). Does unemployment increase crime? Evidence from US data 1974–2000. Journal of Human Resources, 43(2), 413–436. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhr.2008.0022

[12]. Min Zhu, Shan Wen, Yupig Song, Impact of COVID-19 on jump occurrence in capital markets, June 24, 2024.https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/s41599-024-03357-y

[13]. Bo Zhengyuan, COVID-19: Catalyzing U.S.-China Supply Chain Realignments, JULY 30, 2024.https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-54766-9_4

[14]. China National Trade Administration (CNTA), Trading Economics, Sep 26, 2024.https://zh.tradingeconomics.com/china/exports