1. Introduction

Retail behaviours can be defined as people’s buying and spending habits [1]. In recent years, the global retail sector has faced significant challenges, including the rapid rise of online shopping, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, and wider economic crises. These factors have substantially reshaped consumer behaviour, altering not only what people buy but also how, when, and where they purchase. Behavioural changes have had profound implications for retail sites, with some retail formats proving more resilient than others. As a result, the number and types of services offered in different retail environments have been unevenly affected. Understanding these behavioural shifts is crucial, as they influence the sustainability of retail landscapes and the vitality of urban centres.

Central Place Theory laid the foundation for analysing the spatial organisation of retail systems by introducing the concepts of range and threshold [2]. According to Central Place Theory [3], both customers and retailers are assumed to be utility maximisers, with consumers travelling to the nearest available centre to minimise costs, and retailers locating where they can maximise profits. The theory also distinguishes between high-order goods, which are purchased infrequently and require large population thresholds, and low-order goods, which are bought regularly and can sustain smaller centres [4]. Consumers are generally willing to travel longer distances for high-order goods, thereby extending the spatial influence of larger centres [5].

Retail hierarchies demonstrate that the size of a settlement is closely related to the diversity of its services [6], and retail location choice depends not only on distance but also on factors such as accessibility and consumer perceptions [7]. Planning policies and decentralisation have significantly influenced the structure of retailing, reshaping retail landscapes [8]. These observations suggest that while Central Place Theory provides a robust foundation, retail behaviour is also affected by broader social, economic, and policy factors.

Contemporary pressures have further impacted retail behaviour. Shopping centres now experience higher vacancy rates than retail parks, largely due to higher service charges and reduced footfall [9]. This phenomenon has been described as the “death of the high street,” driven by the migration of shoppers to out-of-town locations [10]. Retail parks have remained resilient by integrating online shopping logistics, such as click-and-collect and easy returns [11]. Accessibility continues to draw consumers to town centres, but their competitive advantage has been eroded by peripheral developments [12]. Globalisation and technological innovation have reshaped retail geographies, with online accessibility increasingly competing with physical proximity [13].

Despite this extensive body of work, relatively few studies have investigated how these retail changes manifest within medium-sized urban centres in the UK. Much of the literature either focuses on national-level trends or on major metropolitan areas, leaving a gap in understanding how retail behaviours play out in towns such as Rugby. Furthermore, while Central Place Theory has been widely discussed in theoretical terms, there has been limited empirical testing of its predictions in the context of contemporary challenges such as online shopping and post-pandemic recovery. This creates an opportunity to explore how far observed retail behaviours in different formats (out-of-town retail parks versus CBD shopping centres) conform to or deviate from theoretical expectations.

This study addressed the question: To what extent do retail behaviours at Elliott’s Field and Rugby Central in Rugby conform to the predictions of Central Place Theory? Using fieldwork data on footfall, travel distance, frequency of visits and the distribution of high-order goods, the research compares an out-of-town retail park with a central shopping centre. By evaluating these findings against Central Place Theory, the study contributes to understanding the resilience and transformation of retail formats. The results have broader implications for retail geography and urban planning, particularly in supporting strategies for revitalising town centres.

2. Method

2.1. Study area

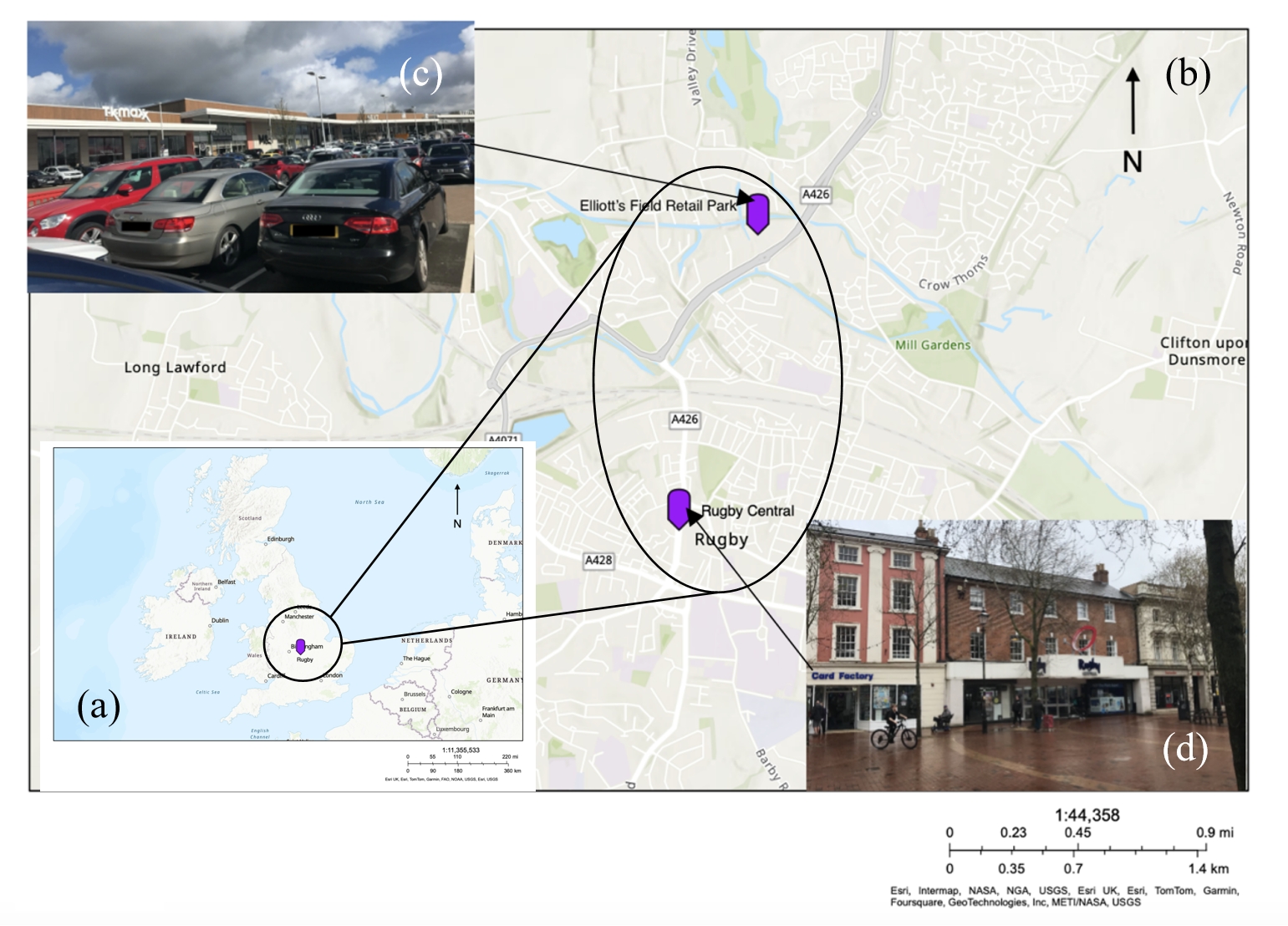

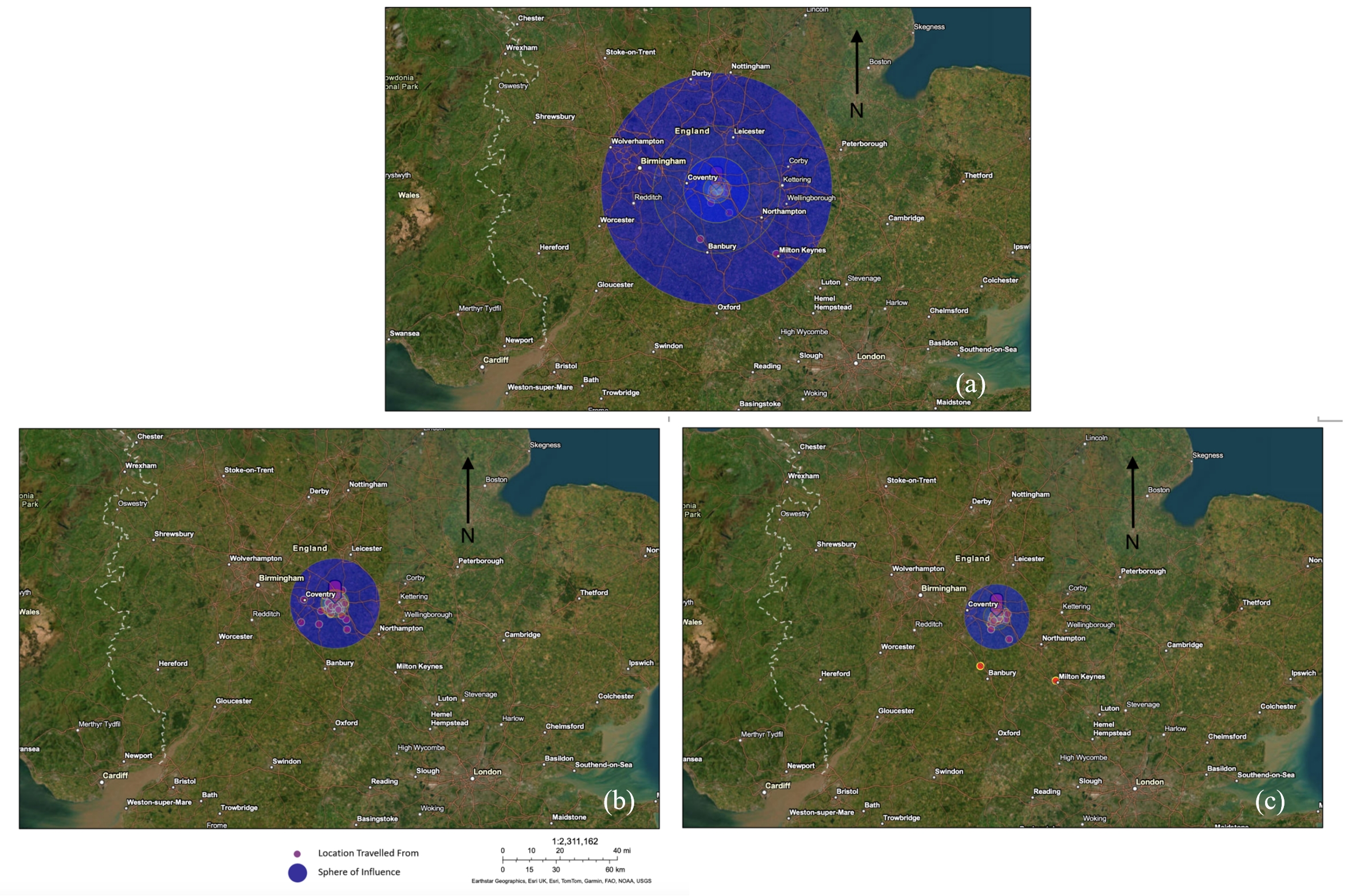

Rugby is a town in Warwickshire in the West Midlands region of England, located 35 miles south-east of Birmingham. According to the 2021 census, Rugby has a population of 114,400. Figure 1 shows the location of the two retail sites investigated: Elliott’s Field (Figure 1c) and Rugby Central (Figure 1d).

Elliott’s Field is an out-of-town retail park in Rugby, covering 320,000 square feet of outdoor retail space, located 0.5 miles north of the town centre. It was first opened in 1987 and underwent redevelopment in 2017. Rugby Central is a shopping centre located in the town centre, offering 210,000 square feet of indoor retail space . The centre was opened in 1980 and refurbished in 2019.

2.2. Data collection

Primary data were collected at both Elliott’s Field and Rugby Central to inform the analysis and evaluate the extent to which observed patterns align with the proposed hypotheses. Footfall was recorded at the main entrances of each site over a 10-minute period, counting only individuals entering to avoid double-counting. The counts were conducted on consecutive Saturdays at 13:30 to ensure consistency, with similar weather conditions to minimise environmental variability.

A structured questionnaire comprising closed questions was administered to customers to gather quantitative data on consumer perceptions and shopping behaviours. The survey was created using ArcGIS, which facilitated efficient data collection and direct integration with GIS for spatial analysis. Convenience sampling was employed by approaching available individuals at each location, and a sample size of 35 participants per site was chosen to capture demographic variability within practical constraints.

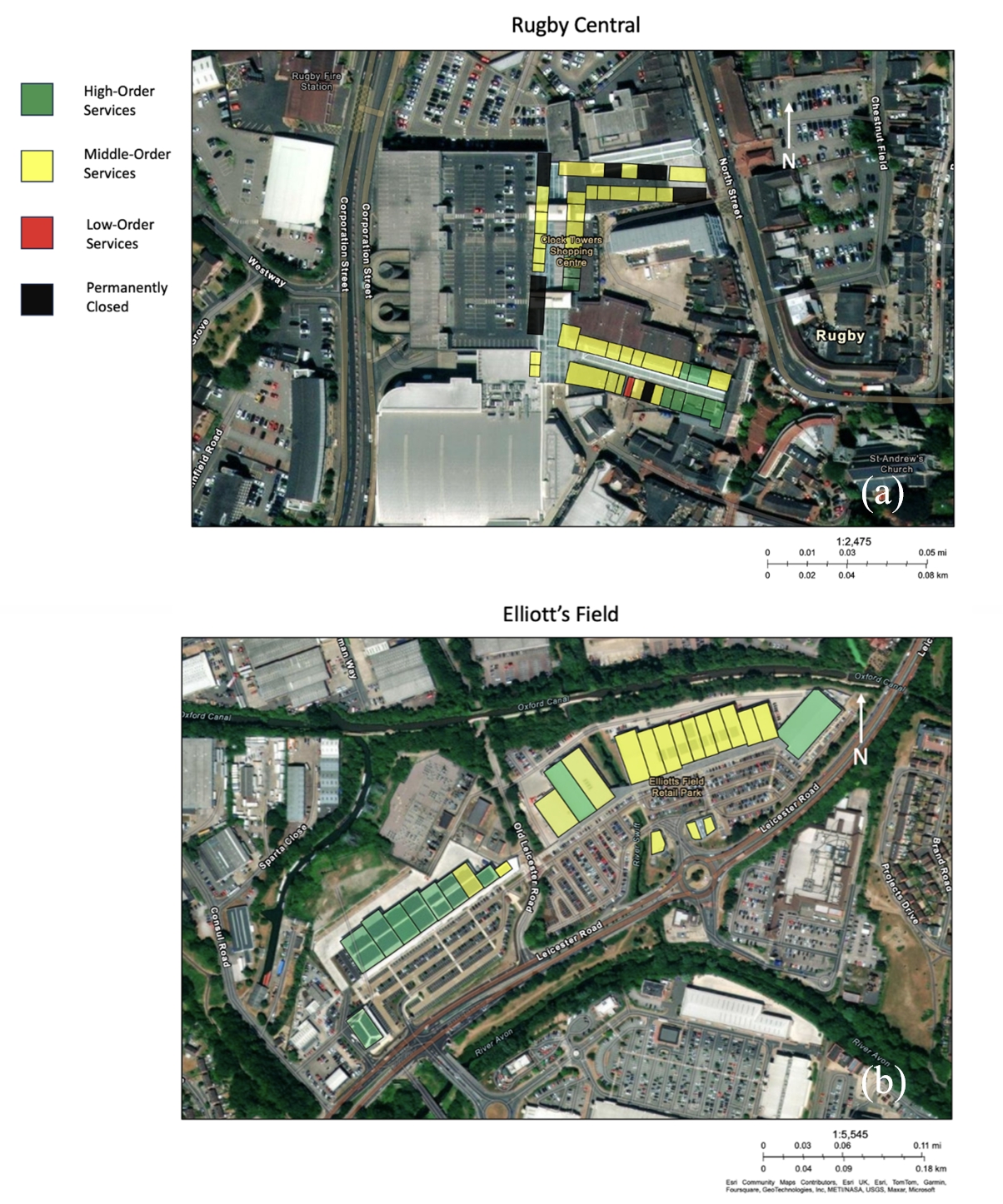

Shops at each site were categorised into high-, middle-, and low-order services to examine their potential spheres of influence. High-order services sell luxury or shopping goods that are bought infrequently, middle-order services sell goods that are purchased less frequently than low-order goods, and low-order services sell necessity or convenience goods that are bought frequently (Dennis, Marsland and Cockett). This classification helps to understand the role of each retail site within the local retail hierarchy.

2.3. ArcGIS mapping and data analysis

All spatial data were processed and visualised using ArcGIS. The locations of Elliott’s Field and Rugby Central were georeferenced using coordinate data and overlaid on UK and local maps to produce multiple map layers, illustrating regional, town, and site-level contexts. Footfall counts and questionnaire responses were imported into ArcGIS to enable spatially referenced analysis, allowing the identification of patterns in customer distribution and site influence.

Shops were mapped according to their service category, and spatial analysis tools were applied to examine the distribution of high-, middle-, and low-order services, their proximity to one another, and the potential extent of each site’s influence. The integration of field data and GIS mapping enabled a comprehensive assessment of retail activity, consumer behaviour, and the spatial organisation of shops at both sites.

2.4. Statistical analysis of distance and frequency

Questionnaire data were used to investigate the relationship between distance travelled and frequency of visits. Distances were recorded directly from respondents, while visit frequency was grouped into four categories: 1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = frequently, 4 = always.

To test for correlation, Spearman’s Rank correlation coefficient was applied.

Null hypothesis (H₀): There is no correlation between distance travelled and frequency of visits.

Alternative hypothesis (H₁): There is a correlation between distance travelled and frequency of visits.

A total of 70 questionnaires were collected, with 35 responses from each site. This allowed the Spearman’s Rank test to be calculated separately for Elliott’s Field and Rugby Central. Critical values for a sample size of 35 were used to determine statistical significance at the 90% confidence level.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Services

Figure 2a and Table 1 illustrate the service classification at Rugby Central, highlighting that the site contains a relatively high number of permanently closed shops (7 in total). This aligns with research indicating that vacancy rates in shopping centres often exceed the national average. The presence of these closed units limits the range of services available, potentially reducing the site’s appeal and restricting the number of customers. As a result, retail behaviours may be influenced, with fewer people visiting Rugby Central due to the decreased diversity of shops, and more customers possibly choosing to visit Elliott’s Field instead. Despite this, the majority of services at Rugby Central are middle-order (31 in total), with one low-order service and ten high-order services. This suggests that the site still provides a reasonably broad range of goods, making it convenient for a diverse customer base. From the perspective of Central Place Theory, customers are utility maximisers and may continue to visit Rugby Central to access a wide range of products in one location.

Figure 2b and Table 2 show the service distribution at Elliott’s Field, where most shops are middle-order (17 in total). The site also contains ten high-order services but no low-order services and no permanently closed shops. This pattern is consistent with Central Place Theory’s prediction that the number of high-order services increases as the size of a settlement grows. However, it deviates from the expectation that both the number and range of functions increase, as Rugby Central offers a greater total number and broader range of services. This discrepancy may be explained by the relative size of shops: while Rugby Central hosts more units, these tend to be smaller than those at Elliott’s Field, likely due to higher rents and service charges. The absence of permanently closed shops at Elliott’s Field is consistent with research showing that vacancy rates are generally lower in retail parks than in shopping centres, suggesting that some businesses may have relocated from Rugby Central to Elliott’s Field to benefit from more favourable operating conditions.

|

High-Order |

Middle-Order |

Low-Order |

Permanently Closed |

|

|

Ruby Central |

10 |

31 |

1 |

7 |

|

Elliott’s Field |

10 |

17 |

0 |

0 |

3.2. Footfall

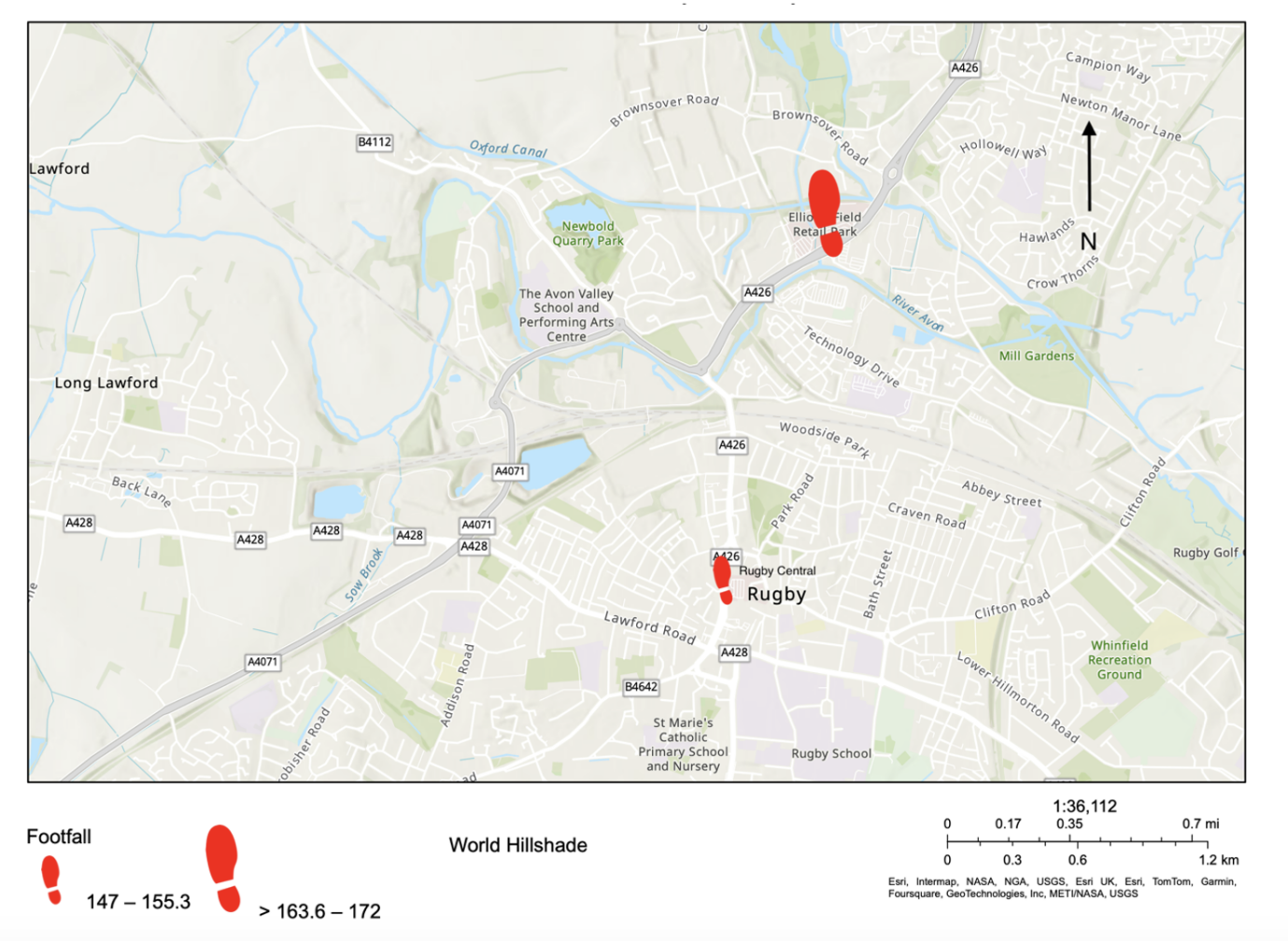

Figure 3 reveals that Elliott’s Field has a higher footfall than Rugby Central, aligning with the hypothesis. However, the footfall values at Rugby Central and Elliott’s Field showed less disparity than expected. Recorded one week apart at the same time, Elliott’s Field registered a footfall of 172 compared to Rugby Central’s 147. This disparity may be attributed to Elliott’s Field’s greater number of high-order services. Central Place Theory explains that high-order goods require a higher threshold (the minimum number of people required to support it) to make them commercially profitable. Therefore, as Rugby Central has a lower number of high-order services and more permanently closed stores and low-order services, a lower threshold is required to make these services commercially profitable. Additionally, the higher footfall at Elliott’s Field may be influenced by the availability of free parking and its convenient out-of-town location, which facilitates car access and expands the customer base.

Higher footfall at Elliott’s Field indicates greater economic activity, supporting research on the growth of retail parks and the decline in shopping centres [14]. The greater economic activity in retail parks enhances their attractiveness to businesses, which may exacerbate cycles of deprivation in traditional shopping centres and drive significant shifts in retail behaviours.

3.3. Spheres of influence

To map the spheres of influence for each retail site, respondents were asked, “Where have you travelled from to reach this retail site?” This information was used to examine the social, political, and economic influence of each site, identify spatial patterns in retail behaviour, assess competition between Elliott’s Field and Rugby Central, and understand the hierarchy of these central places. Due to the personal nature of the question, many respondents provided general areas rather than precise locations, which may have reduced spatial accuracy. Nevertheless, the data were sufficient to effectively map the spheres of influence.

Figure 4a and Figure 4b present the initial spheres of influence for Rugby Central and Elliott’s Field, respectively. The data indicate that Rugby Central has a significantly larger sphere of influence than Elliott’s Field, particularly attracting customers from southern areas such as Banbury and Milton Keynes. This finding is contrary to expectations based on Central Place Theory, which predicts that Elliott’s Field—given its larger size and higher number of high-order services—should draw customers from a wider area. The discrepancy may be partly due to Rugby Central’s central location and the variety of services it offers, including both necessity and specialised goods, despite several permanently closed stores and a predominance of middle- and low-order shops.

To address potential anomalies in the dataset, a revised sphere of influence for Rugby Central was created by excluding outliers (Figure 4c). The revised map shows a reduced sphere of influence, aligning more closely with Central Place Theory, which suggests that customers travel further for high-order goods found at Elliott’s Field. The updated data also reveal a predominantly northward travel pattern to both sites, indicating that consumers beyond a certain distance may prefer alternative retail destinations, such as Leicester or Birmingham, reducing the need to travel to Rugby.

Despite the reduction in sphere size after removing anomalies, Rugby Central may still retain a larger sphere of influence than Elliott’s Field due to its wider range of shops, which provide both necessity and specialised goods, as well as its higher total number of shops. Its central location also confers accessibility advantages, particularly for customers relying on public transport. Overall, the analysis suggests that while Central Place Theory provides a useful framework, factors such as shop variety, accessibility, and urban context can result in deviations from theoretical expectations.

3.4. Frequency of visits

Figure 5 and Table 2 present the results from the questionnaire question, “How frequently do you visit this retail location?” At Elliott’s Field, the most common response was “frequently” (40%), whereas at Rugby Central it was “sometimes” (45.7%). This suggests that Elliott’s Field is generally visited more often. However, a higher proportion of respondents at Rugby Central reported visiting “always” compared to Elliott’s Field (14.3% versus 11.4%), likely reflecting the presence of more low-order services that provide necessity goods purchased regularly. In contrast, Elliott’s Field has a higher proportion of high-order services, which are bought less frequently, contributing to its lower proportion of “always” visits.

Accessibility also appears to influence visit frequency. Rugby Central’s central location benefits customers travelling by foot or public transport, particularly older individuals, while Elliott’s Field primarily serves car-borne customers and is less accessible on foot. Despite this, 28.6% of respondents at Rugby Central reported “rarely” visiting the site, compared with 11.4% at Elliott’s Field, likely due to the number of permanently closed stores diminishing Rugby Central’s overall appeal.

The observed patterns may also relate to the previously mapped spheres of influence. Rugby Central exhibited a larger sphere of influence than Elliott’s Field when anomalies were included. According to Central Place Theory, customers typically visit the nearest available location; therefore, individuals travelling further to access Rugby Central may do so less frequently, explaining why Elliott’s Field, despite a smaller sphere of influence, is visited more often in general.

|

Location |

Always |

Frequently |

Sometimes |

Rarely |

|

Rugby Central |

14.29% |

11.43% |

45.71% |

28.57% |

|

Elliott’s Field |

11.43% |

40% |

37.14% |

11.43% |

3.5. Distance travelled and frequency of visits

According to Central Place Theory, the range of a good depends on its value, the distance customers are willing to travel, and the frequency with which it is required. The theory therefore predicts a negative correlation between distance travelled and frequency of visits, as customers are expected to travel further for higher-order goods that are purchased less frequently.

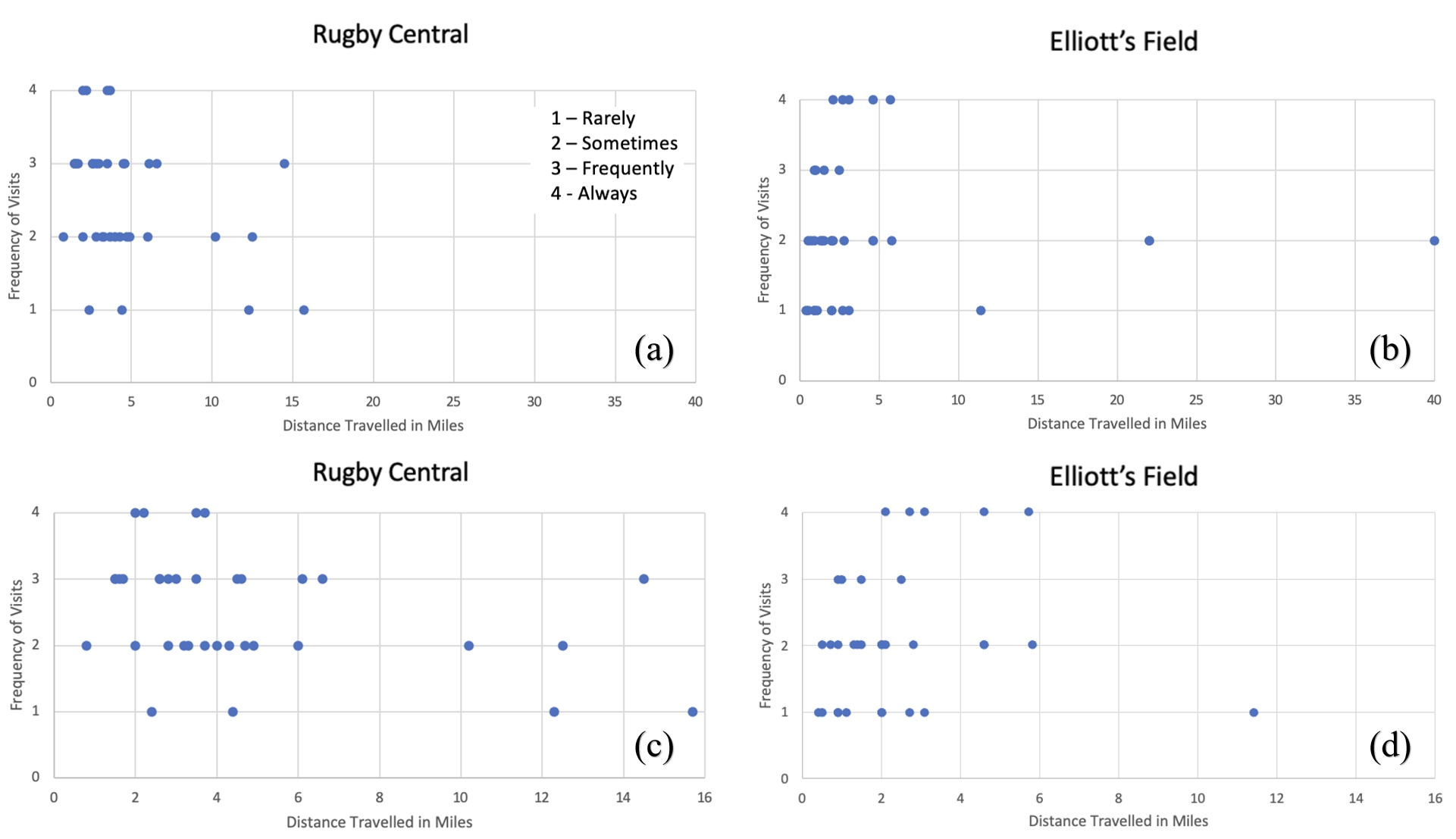

Figure 6 presents scatter graphs illustrating the relationship between distance travelled and frequency of visits. At Rugby Central, two anomalies (22 miles and 40 miles) were excluded to produce the revised graphs. However, even after removing anomalies, the scatter plots show no obvious correlation at either site.

To examine this relationship more rigorously, Spearman’s Rank correlation coefficient was calculated separately for the two retail centres, based on 35 questionnaire responses per site. At Elliott’s Field, the results revealed a very weak negative correlation, with a coefficient close to 0.222 but below the 90% critical value. This indicates that there is no statistically significant relationship, and the observed pattern may be attributable to chance. By contrast, Rugby Central exhibited a weak negative correlation, with a coefficient above the 90% critical value, suggesting that the relationship between distance travelled and frequency of visits is statistically significant in this case.

Although both sites display weak negative correlations, the relationship is stronger and statistically significant at Rugby Central. This may reflect its more central and accessible location, as well as the greater availability of low-order services that are required more frequently. Nevertheless, the reliability of these findings is constrained by the data collection method: visit frequency was recorded in grouped categories (e.g., “weekly,” “monthly”) rather than exact numerical values, thereby reducing the precision of the statistical analysis. Future research would benefit from recording precise frequencies (e.g., number of visits per month) to improve the accuracy and robustness of the results.

4. Conclusion

This study had examined the extent to which retail behaviours in Rugby conform to the predictions of Central Place Theory. The findings showed that Elliott’s Field attracts higher footfall and hosts more high-order services, while Rugby Central maintains a broader but less resilient mix of shops, with vacancy rates affecting its appeal. Despite theoretical expectations, Rugby Central displayed a larger sphere of influence, and only at this site was a statistically significant negative correlation identified between distance travelled and frequency of visits.

By focusing on a medium-sized town, this research filled a gap in the literature, which has largely concentrated on national trends or major metropolitan centres. It demonstrated that while Central Place Theory provided a useful framework, contemporary retail behaviour is shaped by additional factors, including accessibility, service diversity, and the impacts of online shopping and urban restructuring. The study is limited by the use of categorical rather than exact frequency data and by a modest sample size. Future research should adopt larger datasets and continuous measures of behaviour to increase robustness. Nonetheless, the findings are significant in highlighting the shifting dynamics of retail formats, offering insights for policymakers and planners seeking to revitalise town centres and manage the balance between out-of-town retail parks and central shopping districts.

References

[1]. Lee, J.G., Kong, A.Y., Sewell, K.B., Golden, S.D., Combs, T.B., Ribisl, K.M. and Henriksen, L. (2022) Associations of Tobacco Retailer Density and Proximity with Adult Tobacco Use Behaviours and Health Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis. Tobacco Control, 31, e189-e200.

[2]. Parr, J.B. (2025) Walter Christaller (1893–1969): Originator of Central Place Theory. In Great Minds in Regional Science, Vol. 3, 17-34. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

[3]. Maddrell, A. (2016) Mapping Grief: A Conceptual Framework for Understanding the Spatial Dimensions of Bereavement, Mourning and Remembrance. Social & Cultural Geography, 17, 166–188.

[4]. Gill, J.C. and Malamud, B.D. (2014) Reviewing and Visualizing the Interactions of Natural Hazards. Reviews of Geophysics, 52, 680-722.

[5]. Dennis, C., Marsland, D. and Cockett, T. (2002) Central Place Practice: Shopping Centre Attractiveness Measures, Hinterland Boundaries and the UK Retail Hierarchy. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 9, 185-199.

[6]. Eppli, M. and Benjamin, J. (1994) The Evolution of Shopping Center Research: A Review and Analysis. Journal of Real Estate Research, 9, 5-32.

[7]. Brown, S. (1987) Institutional Change in Retailing: A Geographical Interpretation. Progress in Human Geography, 11, 181-206.

[8]. Wadinambiaratchi, G.H. and Girvan, C. (1972) Theories of Retail Development. Social and Economic Studies, 391-403.

[9]. Crawford, A. (2006) ‘Fixing Broken Promises?’: Neighbourhood Wardens and Social Capital. Urban Studies, 43, 957-976.

[10]. Morris, G. (2022) The Implications of COVID-19 and Brexit for England's Town Councils: Views from the Town Hall, and Beyond. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 26, 114-138.

[11]. Warrington, O. and Seares, L. (2016) The Resilience of Retail Parks. Journal of Retail and Distribution, 44, 123-138.

[12]. Hope, J. (2016) Losing Ground? Extractive-Led Development versus Environmentalism in the Isiboro Secure Indigenous Territory and National Park (TIPNIS), Bolivia. The Extractive Industries and Society, 3, 922-929.

[13]. Findlay, A., Jackson, M., McInroy, N., Prentice, P., Robertson, E. and Sparks, L. (2018) Putting Towns on the Policy Map: Understanding Scottish Places (USP). Scottish Affairs, 27, 294-318.

[14]. Reynolds, J., Howard, E., Dragun, D., Rosewell, B. and Ormerod, P. (2005) Assessing the Productivity of the UK Retail Sector. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 15, 237-280.

Cite this article

Butler,J. (2025). Central Place Theory and Retail Behaviours: A Case Study of Rugby’s Retail Sector. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,240,138-147.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICFTBA 2025 Symposium: Data-Driven Decision Making in Business and Economics

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Lee, J.G., Kong, A.Y., Sewell, K.B., Golden, S.D., Combs, T.B., Ribisl, K.M. and Henriksen, L. (2022) Associations of Tobacco Retailer Density and Proximity with Adult Tobacco Use Behaviours and Health Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis. Tobacco Control, 31, e189-e200.

[2]. Parr, J.B. (2025) Walter Christaller (1893–1969): Originator of Central Place Theory. In Great Minds in Regional Science, Vol. 3, 17-34. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

[3]. Maddrell, A. (2016) Mapping Grief: A Conceptual Framework for Understanding the Spatial Dimensions of Bereavement, Mourning and Remembrance. Social & Cultural Geography, 17, 166–188.

[4]. Gill, J.C. and Malamud, B.D. (2014) Reviewing and Visualizing the Interactions of Natural Hazards. Reviews of Geophysics, 52, 680-722.

[5]. Dennis, C., Marsland, D. and Cockett, T. (2002) Central Place Practice: Shopping Centre Attractiveness Measures, Hinterland Boundaries and the UK Retail Hierarchy. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 9, 185-199.

[6]. Eppli, M. and Benjamin, J. (1994) The Evolution of Shopping Center Research: A Review and Analysis. Journal of Real Estate Research, 9, 5-32.

[7]. Brown, S. (1987) Institutional Change in Retailing: A Geographical Interpretation. Progress in Human Geography, 11, 181-206.

[8]. Wadinambiaratchi, G.H. and Girvan, C. (1972) Theories of Retail Development. Social and Economic Studies, 391-403.

[9]. Crawford, A. (2006) ‘Fixing Broken Promises?’: Neighbourhood Wardens and Social Capital. Urban Studies, 43, 957-976.

[10]. Morris, G. (2022) The Implications of COVID-19 and Brexit for England's Town Councils: Views from the Town Hall, and Beyond. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 26, 114-138.

[11]. Warrington, O. and Seares, L. (2016) The Resilience of Retail Parks. Journal of Retail and Distribution, 44, 123-138.

[12]. Hope, J. (2016) Losing Ground? Extractive-Led Development versus Environmentalism in the Isiboro Secure Indigenous Territory and National Park (TIPNIS), Bolivia. The Extractive Industries and Society, 3, 922-929.

[13]. Findlay, A., Jackson, M., McInroy, N., Prentice, P., Robertson, E. and Sparks, L. (2018) Putting Towns on the Policy Map: Understanding Scottish Places (USP). Scottish Affairs, 27, 294-318.

[14]. Reynolds, J., Howard, E., Dragun, D., Rosewell, B. and Ormerod, P. (2005) Assessing the Productivity of the UK Retail Sector. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 15, 237-280.