1. Introduction

The Chinese economy has enjoyed high-speed development without stopping for decades. In recent years, since the COVID-19 pandemic, deep challenges have been exposed, growth has sharply decelerated, the once-booming housing market has faltered, and signs of deflationary pressure have emerged. These trends have drawn frequent comparisons to Japan’s infamous “Lost Decades” of the 1990s and 2000s, when an asset bubble collapse led to prolonged stagnation [1]. Indeed, the parallels are striking in China’s current situation, with low aggregate demand and high debt mirroring the conditions Japan faced after its early-1990s housing bubble burst. Therefore, countless researchers have emphasised their concern with the Chinese economic recession, with illustrating that China will suffering their own “Lost Decades”.

History does not have to repeat itself in the same way. This essay examines the causes of aggregate-demand shortfalls and the macroeconomic policies that characterised Japan’s Lost Decades, comparing them to the measures currently being implemented in China. Investigating the macroeconomic lessons that could help Beijing avoid a similar prolonged period of stagnation. Additionally, this paper employs a comparative approach to draw insights from Japan’s experience, with the aim of guiding China toward a more stable and prosperous economic future, thereby preventing a repeat of its own “lost decade.”

1.1. Research significance

This study highlights the importance of comparing Japan’s Lost Decades with China's current macroeconomic strategies to offer insights into demand-driven stagnation. It analyses demand shortfalls and policies in both economies, revealing vulnerabilities and mistakes that could prolong stagnation. By comparing data from government authority statistics with the current situation China is facing, this analysis identifies similarities and differences to help Beijing’s policymakers make informed decisions.

1.2. Research theme method

This study presents a case study and comparative analysis using secondary data to identify the true causes of China’s economic slowdown. While many suggest the COVID-19 pandemic as the main driver, this study argues that it masks deeper structural problems. The significant decline in the real estate sector has revealed issues as high corporate and local government debt, reduced household spending, and declining private-sector confidence. Using a comparative approach, this study examines China’s current situation alongside Japan’s experience during the Lost Decade of the 1990s, when a property bubble burst, similarly exposing systemic flaws. By placing China’s slowdown in a broader historical and international context, this analysis illustrates that COVID-19 acted more as a trigger than the root cause. The essay uses secondary data to demonstrate that China’s crisis extends beyond the temporary impact of the pandemic.

2. Literature review

2.1. Limitations

Despite the case of China and Japan having several similarities to compare, limitations still exist. The analysis of official Chinese statistics faces two major limitations because official data may not show the complete picture and international agencies use different methods to create their estimates which makes comparison between them difficult. The analysis depends on historical similarities instead of economic evidence which makes it impossible to establish direct cause-and-effect relationships between policy decisions and their economic outcomes. The application of lessons becomes challenging because Japan in the 1990s differs from present-day China through various factors including demographic changes and financial openness and political structures and state-owned enterprise influence. Therefore this research investigates domestic aggregate-demand solutions to economic stagnation by analysing both supply-side elements and international factors that affect stagnation risks.

2.2. Country contexts, Japan

The "Lost Decades" period started after Japan achieved notable economic growth and development before the era of stagnation. Japan started its economic growth and industrialization after World War II while experiencing the Cold War and Korean War era to reach remarkable economic success. The beginning of conflict with the United States triggered a surge in Japanese export activities which led to national economic growth. Japan achieved economic recovery through yen stabilization and dollar pegging which enabled both steady US trade relations and reduced US consumer prices for Japanese goods. During the 1980s Japan emerged as the world's second-largest economy.

The post-1980s economic stagnation period in Japan has been called the "Lost Decades" which spanned about twenty years. The asset bubble collapse in 1990 triggered a severe decline in asset prices and a banking crisis because many loans became worthless. The economy faced a sustained decrease in aggregate demand after the crisis since companies and households accumulated excessive debt and lost substantial wealth which forced them to reduce spending to fix their financial situation. Economists later identified this period as a "balance sheet recession" because private entities focused on debt repayment instead of spending or investing. The economy faced a prolonged period of weak demand while factories operated below capacity and prices fell continuously which produced an unfavourable economic pattern.

The economic stagnation of the "Lost Decades" has caused significant changes to both Japanese economy and population and customer purchasing behaviour. The prolonged time of low demand throughout society began to shift only recently. According to the Statistics Bureau of Japan holds the title of oldest population in the world because more than 28% of its citizens have reached age 65 or older [2]. The exceptional demographic profile of Japan results from its long life expectancy alongside minimal population growth which created a distinct population structure.

2.3. Country contexts, China

The Chinese economy stands out as a remarkable success story. Over the past four decades, China has achieved extraordinary economic growth, all while maintaining an authoritarian political regime [3]. This regime has enjoyed over a decade of sustained economic prosperity, a direct result of Deng Xiaoping's decisive "Reform and Opening Up" policy implemented in the 1980s. Leading China to adopt a state-owned capitalist economic system with most resources monopolised by the central government [4]. This centralised reform provided significant convenience for adjustment, thereby establishing a foundation for long-term economic stability.

Since the early 21st Century, China's wealth accumulation has been driven by its membership in the WTO and the export of goods and services worldwide. Meanwhile, the housing market increased rapidly. Wang and Hui, summarising some recent studies on China’s housing market, have revealed essential insights [5]. They recommend that Chinese mayors sell public land as quickly as possible to fund infrastructure projects. This further explains the high number of housing vacancies, noting that between 2003 and 2012, local politicians sold 7.4% more land in response to economic growth incentives. Meanwhile, budgetary revenues and intergovernmental transfers were highly reliant on most Chinese cities. Notice that land transfer revenue is primarily for local economic development rather than social programs [6].

Furthermore, in 2008, Wen Jiabao, the former Prime Minister of China, allocated four trillion yuan to counteract the effects of the global economic recession. This money was mainly used for government spending on civil infrastructure. Indeed, this decision saved the macroeconomy at that time. However, this created a hidden threat in the Chinese economy. Nowadays, the core of China’s slowdown is an aggregate-demand issue coupled with high government debt. Weak consumption, combined with economic decline, has led to low business confidence, and investment has fallen sharply. Facing uncertain geopolitical challenges amid the trade war with the U.S., causing further difficulties for China, which is an economic exporter.

3. Case study I: Japan’s lost decades & policy responses

Japan has struggled with sustained economic growth, having gone through several recessions since the early 1990s. Following the remarkable economic boom of the 1980s, when asset prices surged to record highs due to loose monetary conditions and financial deregulation. In those days, a combination of factors, including relaxed lending standards, deregulation of the financial sector, and the illusion of continuously rising asset values, led banks to lend more freely, often with more lenient collateral requirements [7]. By late 1989, the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s Nikkei 225 index exceeded 38,000, and urban land values in Tokyo increased by over 60% in five years [8]. Across Japan, the surge in average house prices was almost entirely driven by rising land values, with structural costs playing a secondary role. These trends led to the market value of land in central Tokyo alone being estimated to surpass the total land value of the United States during the 1980s [9]. Corporate and household balance sheets became dangerously exposed to inflated asset prices, and speculative behaviour spread. Based on this situation, the Bank of Japan [BoJ], wary of overheating, began modest tightening measures in the late 1980s. However, the interest rate increases were not sufficiently aggressive to curb enthusiasm, ultimately setting the stage for a much sharper crash [10].

Macroeconomic policy responses in Japan during the 1990s were often criticised as insufficient and delayed [11]. Early on, authorities were hesitant to implement strong monetary or fiscal easing in response to the economic slowdown. Although the Bank of Japan gradually lowered interest rates approaching zero by the mid-1990s. This limited effectiveness as the economy entered a liquidity trap, where monetary policy could no longer stimulate activity. Fiscal efforts included several stimulus packages, mainly spending on public works to boost demand, but these were sometimes reversed due to concerns over mounting deficits. A significant error was the 1997 increase in the consumption tax, which disrupted an emerging recovery [11]. Overall, fiscal measures were perceived as inconsistent and inadequate, and by the late 1990s, deflation emerged. As expectations of falling prices took hold, consumers restrained spending, expecting lower prices and further dampening demand.

Crucially, Japan’s financial system issues exacerbated the demand shortfall. Banks, overloaded with non-performing loans, hesitated to offer new credit. Instead of forcing quick write-offs, authorities permitted banks to support "zombie” firms, thereby hindering a Schumpeterian process of creative destruction. This kept many inefficient companies afloat, reducing overall productivity and investment while business confidence remained low. By the late 1990s, Japan experienced nearly zero GDP growth and ongoing deflation, illustrating a deep economic stagnation. In the 2000s, Japan’s belated policy innovations, such as quantitative easing, banking sector clean-up, and later the “Abenomics” agenda, did stabilise the economy, but growth remained anaemic. However, growth remained sluggish. In effect, Japan spent two decades with its economy performing below potential, a result of persistent demand shortages.

As the analysis noted by Callen & Ostry, Japan’s potential growth declined in part due to a drop in total factor productivity and a lack of new firm dynamism during the lost decades [12]. The Japanese experience underscored how difficult it can be to escape a demand-driven stagnation once deflationary psychology sets in. It also highlighted pitfalls of policy: delay in responding to the crisis, half-measures in stimulus, and structural impediments (like zombie firms) all contributed to the protracted slump.

4. Case study II: China’s current macroeconomic challenges

China’s post-pandemic slowdown can be seen as a typical shortfall in aggregate demand combined with balance-sheet pressures. Consumer activity remains weak, confidence among businesses and households has declined, and investment has slowed, especially as the property market stalls. Causing the GDP deflator to decrease and kept headline inflation near zero—a sign of potential deflation—while producer prices decline. All these issues occur amid high debt levels in important parts of the government sector. These factors set the stage for three urgent short-term issues: the dynamics of government debt, the connection between property and fiscal stability, and a simultaneous reduction in consumption and exports.

4.1. Government debt

The most immediate fiscal vulnerability is not Beijing’s on-balance-sheet debt but the accumulation of liabilities at sub-national levels—particularly in local government financing vehicles [LGFVs]. These entities borrowed extensively during the 2010s to finance infrastructure and land development [13]. However, they now face reduced cash flows as land sales and property activities slow down. That pressure is significant because LGFVs are interconnected with banks and bond markets; deleveraging in this area restricts local investment, delays project completion, and consumes financial intermediation capacity that could otherwise support private activity. Essentially, LGFV balance-sheet repair drives the same “paradox of thrift” dynamics that characterised Japan’s balance-sheet recession, reducing new lending and deepening weak demand.

Pan et al. argued that in land finance and inter-jurisdictional competition, local government actions might jeopardise the long-term development of Chinese cities [14]. Among these, the overall public sector debt situation worsens this issue. Years of growth driven by investment have left local governments and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) with high debt levels. When these borrowers cut back simultaneously, due to lower revenues and higher refinancing costs, overall investment declines, even as private companies become more cautious. The slowdown in growth is greater than any single borrower’s impact because banks tighten their risk appetite, despite falling policy rates. That’s why a small easing cycle by the central bank has not fully boosted credit demand.

4.2. Housing bubble combing with government revenue

An et al. show—using a vector error-correction model—that foreign capital inflows have a significant, positive effect on China’s house prices even after controlling for income, land supply, and credit policy, and that the effect varies by province and city [15]. Research shows that strict global financial conditions resulting in extended housing inflow reductions will produce lower prices which should influence housing policy choices.

The property downturn has been the main growth constraint since 2021 because developer defaults and declining sales and construction delays have reduced market activity. The economic shock from the crisis has spread to materials and home durables and local services because property represents 20-30% of GDP which has resulted in job losses and reduced household assets. Local governments generate most of their revenue from land-transfer activities so reduced land auction performance results in budget deficits that force them to reduce spending or take on additional debt during economic downturns. The combination of high down payment requirements reduces mortgage default risks but the market decline and uncompleted construction projects lead to increased precautionary saving which keeps consumption levels low even after interest rate reductions.

4.3. Consumption & export crisis

On the domestic side in China, the consumption share has long been structurally low relative to peers. Recent nationally representative surveys reveal a marked shift towards viewing inequality as fundamentally unfair and expect lower income growth by 2023, aligning with increased precautionary measures. Savings increase and weaker consumption despite rate cuts [16]. This indicates significant savings among households and firms, and notably, limited social insurance. When uncertainty rises, a weak safety net induces households to save more for healthcare, education, and retirement, depressing the marginal propensity to consume just when stimulus most needs traction. In Japan’s 1990s stagnation, a comprehensive welfare state cushioned incomes; China lacks that buffer, which makes demand management harder and downturns more deflationary. Strengthening social protection is therefore not only equity-enhancing but macro-stabilising.

The price data indicates a demand gap. With nominal growth subdued by a negative GDP deflator and CPI close to zero, China risks repeating Japan’s deflation experience—where expectations become 'sticky’ at low levels, leading households to delay purchases and firms to hold back on investment [17-19]. To counter this, clearly communicating a pro-inflation stance and providing targeted support that injects cash into consumers’ hands could help break this negative cycle.

Externally, the playbook that previously compensated for weak consumption by increasing exports now appears less dependable. With global growth remaining subdued, supply chains have been reorganised, and geopolitical tensions- especially tariffs and technology restrictions caused by the rivalry between the U.S. and China- restrict market access and affect the ripple effects of manufacturing improvements [7]. Figure 1 demonstrates that tariffs initially correlated with a lower export-to-import ratio, declining from 2017 to 2019. However, the ratio sharply increased again after 2020 as U.S. demand, price effects, and import compression became more significant than penalties. During the immediate rebound from the pandemic, exports provided a temporary boost; as that diminished, the economy lacked an alternative stimulus. This reflects the core of today’s “dual gap”: internal demand too weak to sustain growth, external demand too contested to depend on safely.

Moreover, prioritising surpluses can worsen domestic malaise. Persistently running external surpluses is, by the accounting identity, evidence that national savings exceed investment; when investment is declining, larger surpluses may reflect an even deeper domestic demand shortfall, with the condition that property and LGFVs are deleveraging. In circumstances, mercantilist pressure releases some steam through factories but keeps prices subdued at home and invites protectionist resistance abroad. This is exactly the situation Japan faced before, and it is also the risk China currently faces.

5. Comparative analysis & political economy insights

China currently experiences multiple economic problems that match the factors which extended Japan's stagnation period through private sector debt reduction from property market collapse and insufficient domestic consumption to replace export and investment growth and deflationary trends and excessive debt that restricts policy choices. The current economic situation in China shows signs of a potential "lost decade" of slow growth and deflationary trends according to experts who identify multiple similarities with Japan's past economic stagnation [1]. The path forward requires us to study both the matching elements and unique aspects between China's present economic state and Japan's historical period of stagnation.

The study of Japan's Lost Decades and China's current economic slowdown shows both matching and distinct elements regarding total demand deficiencies and government intervention methods. The asset bubble collapse in 1990 led Japan into a long-lasting "balance sheet recession" where people focused on debt repayment instead of making new purchases. The combination of deflation and underutilized production capacity persisted because of multiple rounds of fiscal stimulus and zero-interest-rate policies. The Chinese economy faces a dual challenge from a long-lasting real estate market decline and insufficient household spending and rising municipal debt levels. The official statistics show that Chinese banks continue to provide substantial lending services. The four-trillion-yuan stimulus China implemented in 2008 produced short-term economic growth but did not resolve fundamental issues with state-owned enterprises and the government's dependence on land revenue.

5.1. Countries’ case comparison

Japan’s prolonged stagnation partly stems from the yen surge after the Plaza Accord in the late 1980s, which contributed to its asset bubble burst. Conversely, China’s growth accelerated after 1994 following significant tax and exchange-rate reforms and gained further momentum with WTO accession in 2001–02 [20]. According to the World Bank, real GDP growth reached nearly 14% in 2007 before slowing to around 6% by 2019 [21]. The COVID-19 pandemic then provided a convenient political narrative for the slowdown, despite underlying challenges having already appeared.

Both countries experienced a Real Estate Boom and Bust, characterised by massive real estate bubbles that ultimately burst. Japan’s land prices more than doubled in the 1980s before crashing in the early 90s; China experienced two decades of housing mania leading up to a peak around 2017-2020, with prices in many cities soaring and construction reaching fever-pitch levels [7]. In both cases, real estate was a speculative haven and a key driver of growth until the music stopped. China’s housing market has slowed down since 2021, with developers defaulting and projects being halted. This development "echoes what happened in Japan ten years after its 1980s bubble” [1]. Crucially, the property busts left large debt overhangs [banks in Japan, property developers and LGFVs in China] and shattered investor confidence. The sharp deceleration in fixed-asset investment [FAI] highlights this trend: Japan’s investment growth dropped from about 4.7% annually in the 1980s to nearly zero in the 1990s, while China’s FAI growth, which exceeded 14% in the 2000s, decelerated to around 7% in the 2010s as the real estate sector cooled.

5.2. High savings and low consumption situation

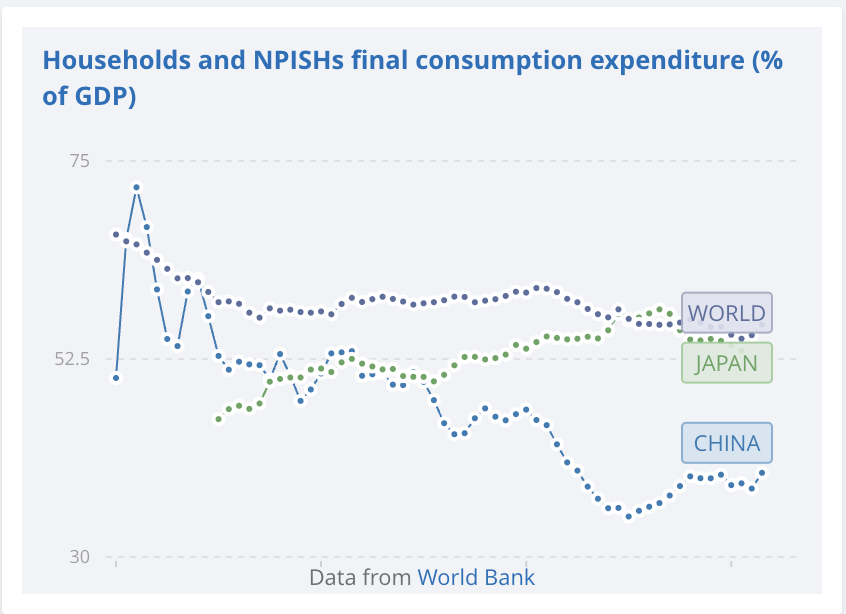

Both Japan and China have experienced this situation in the past, marked by unusually high savings rates and relatively low domestic consumption. Even before its bubble burst, Japan in the 1980s had a savings glut that financed investment booms and current account surpluses. China, for its part, has carried an even larger imbalance – Chinese households and firms save a huge portion of income, and private consumption as a share of GDP has been very low, often around only 35% of GDP in the 2010s, far below global norms (see Figure 2).

Domestic demand was structurally fragile in both cases. Both countries could finance high investment through domestic savings, leading to current account surpluses. However, when investment declines, as it did after the bubbles, and consumption doesn't increase spontaneously, overall demand weakens. Japan's consumption share rose in the 1990s due to household dissaving, partly because wages stagnated and government deficits increased [18, 22].

In contrast, China maintains a high savings rate despite its growth slowdown [23]. One reason China’s saving rate is so high is the absence of a strong welfare state or public insurance – people save for education, health, and old age because government support is limited [24]. Furthermore, He & Cao illustrated that Chinese household savings are deposited in banks, and the majority of external financing for businesses comes from bank loans [25]. This increases the risks faced by the banking system in China.

Not to mention that in both countries, initial hesitation to apply massive stimulus contributed to a longer adjustment period. These parallels justify the comparison and the concern: China could indeed be headed for Japan-style “lost decades” if these issues are not effectively addressed. However, it’s not a certain outcome. There are important differences between China’s situation and Japan’s, and understanding those differences is essential to evaluating what policy path China can and should follow.

5.3. Key differences between China and Japan’s economic context

Institutionally, the two countries exhibit significant institutional differences due to their distinct development levels, population risks, and growth prospects. China operates a state-led economy, which enables more government control, and its policy framework differs from Japan's approach during the 1990s. These differences suggest that China may not experience Japan’s stagnation, with results depending on policy choices. China possesses tools which enable it to prevent major economic disasters, including financial breakdowns and industrial slowdowns. Japan operates a financial system based on liberalisation principles, which stands apart from China's state-capitalist model that implements centralised control for rapid stimulus delivery, yet struggles with resource allocation problems. The middle-income trap could become a persistent trap for China if its policies prove to be incorrect [26].

China uses its macroeconomic strategy to combine demand stimulation with balance sheet repair and structural reforms which will prevent a lost decade while maintaining social stability. The Japanese situation demonstrates that economic expansion serves as the only solution to resolve structural issues because deflationary periods block all reform efforts. The Chinese government needs to provide immediate financial aid to particular industries while improving economic data transparency and market access for private enterprises to win back their trust. However, the challenges of China’s macroeconomy are deeply interconnected. Local-government debt hampers public investment and crowd’s out private credit; the downturn in the property market diminishes household wealth and land-sale revenues; and weak consumption is unlikely to be offset by exports amid rising protectionism [1]. A unified strategy becomes necessary because it enables fast restructuring of LGFVs and developers with financial problems to access their resources complete pre-sold housing projects and stabilize land market prices to enable municipalities to restore their revenue streams The government needs to create targeted short-term support initiatives which will increase consumer purchasing activity The government must create enduring solutions by developing better social insurance programs and productivity improvement strategies to sustain consumption [2-4]. The implementation of these measures at a fast pace will help reduce the chances of Japan experiencing an extended period of stagnation.

6. Conclusion

China's economic downturn shows signs of Japan's Lost Decades which could result in deflationary stagnation if the core issues persist. China faces a long-term economic stagnation but its current development stage and existing policies together with worldwide circumstances create possibilities to prevent an extended period of stagnation. China needs to adopt Japan's strategy of increasing demand and fixing non-performing loans and fighting deflationary attitudes to achieve its goals. The country should use its advantages in coordinated policy-making and economic growth potential and structural changes to drive reform efforts for growth rebalancing. The primary difficulty lies in moving away from investment and real estate dependence toward consumption and innovation without causing a major economic decline. China faces a critical decision regarding its future policies which will decide if the country will experience a “lost decade.” The economy will transition to a new development path at a managed growth rate through the implementation of demand support measures together with structural reforms. The stagnation of Chinese society would create negative impacts on both Chinese society and the global economy. Japan proves that both demand shortage prevention and quick response systems are essential for achieving business success. China's achievement in this area would help the country transition from economic bubbles to sustainable growth but an extended economic decline cannot be ruled out. Beijing possesses both the time and resources needed to study historical lessons which will enable it to prevent future economic crises because China's economic decisions affect worldwide markets.

References

[1]. State Street. (2024). China’s future and the echoes of Japan’s lost decades (White paper). State Street Corporation. https: //www.statestreet.com/web/insights/articles/documents/is-china-the-next-japan-whitepaper-final.pdf

[2]. Statistics Bureau. (2024). Statistics bureau home page/population estimates/current population estimates as of october 1, 2024. Stat.go.jp. https: //www.stat.go.jp/english/data/jinsui/2024np/index.html

[3]. Fewsmith, J. (2008). China since Tiananmen: from Deng Xiaoping to Hu Jintao, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

[4]. Gruin, J., & Manchester University Press. (2019). Communists constructing capitalism: State, market, and the party in china's financial reform. Manchester University Press. https: //doi.org/10.7765/9781526135339

[5]. Wang, Y., & Hui, E. C. M. (2017). Are local governments maximizing land revenue? Evidence from China. China Economic Review, 43, 196-215.

[6]. Li, H. (2016). An empirical analysis of the effects of land-transfer revenues on local governments’ spending preferences in China. China (National University of Singapore. East Asian Institute), 14(3), 29-50. https: //doi.org/10.1353/chn.2016.0031

[7]. García-Herrero, A. and J. Xu (2025) 'Will China’s economy follow the same path as Japan’s? ’Policy Brief 09/2025, Bruegel

[8]. Macrotrends. (2009). Nikkei 225 Index - 67 Year Historical Chart. Macrotrends.net. https: //www.macrotrends.net/2593/nikkei-225-index-historical-chart-data

[9]. Noguchi, Y. (1994). Land prices and house prices in Japan. In Y. Noguchi & J. Poterba (Eds.), Housing markets in the U.S. and Japan (pp. 11–28). University of Chicago Press. http: //www.nber.org/chapters/c8819

[10]. Itoh, M., Koike, R., & Shizume, M. (2015). Bank of Japan's Monetary Policy in the 1980s: A View Perceived from Archived and Other Materials (No. 15-E-12). Institute for Monetary and Economic Studies, Bank of Japan.

[11]. Kuttner, K. N., & Posen, A. S. (2001). The great recession: Lessons for macroeconomic policy from japan. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2001(2), 93-160. https: //doi.org/10.1353/eca.2001.0019

[12]. Callen, T., & Ostry, J. D. (Eds.). (2003). Japan’s Lost Decade: Policies for Economic Revival. International Monetary Fund. Chapter: Callen, T., & Nagaoka, T. (2003). Structural reforms, information technology, and medium term growth prospects.

[13]. Wu, F. (2022). Land financialisation and the financing of urban development in china. Land use Policy, 112, 104412. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104412

[14]. Pan, F., Zhang, F., Zhu, S., & Wójcik, D. (2017). Developing by borrowing? Inter-jurisdictional competition, land finance, and local debt accumulation in China. Urban Studies (Edinburgh, Scotland), 54(4), 897-916.

[15]. An, H., Yu, L., & Gupta, R. (2016). Capital inflows and house prices: Aggregate and regional evidence from china. Australian Economic Papers, 55(4), 451-475. https: //doi.org/10.1111/1467-8454.12095

[16]. Alisky, M., Rozelle, S., & Whyte, M. K. (2025). Getting ahead in Today’s china: From optimism to pessimism. The China Journal (Canberra, A.C.T.), 93(1), 1-22. https: //doi.org/10.1086/733178

[17]. Huang, T. (2024). Lessons from China's fiscal policy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper, (24-7).

[18]. Fukunaga, I., Hogen, Y., & Ueno, Y. (2024). Broad-Perspective Review Series Broad Perspective Review Japan’s Economy and Prices over the Past 25 Years: Past Discussions and Recent Issues Bank of Japan Working Paper Series. https: //www.boj.or.jp/en/research/wps_rev/wps_2024/data/wp24e14.pdf

[19]. Alim, A. N., & Leahy, J. (2025, January 10). Falling Chinese bond yields signal concern with deflation. @FinancialTimes; Financial Times. https: //www.ft.com/content/6fe07039-eb7d-47d9-8e97-e933bab0085a

[20]. Tyers, R. (2012). Japanese economic stagnation: Causes and global implications. The Economic Record, 88(283), 517–536. https: //doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4932.2012.00834.x

[21]. The World Bank. (2023). GDP growth (annual %) – China. World Bank. https: //data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?locations=CN

[22]. Latsos, S., & Schnabl, G. (2021). Determinants of Japanese household saving behavior in the low-interest rate environment. The Economists’ Voice, 18(1), 81–99. https: //doi.org/10.1515/ev-2021-0005

[23]. OECD. (2025). OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2025 Issue 1: Tackling uncertainty, reviving growth. OECD Publishing. https: //doi.org/10.1787/83363382-en

[24]. Wright, L., Boullenois, C., Jordan, C. A., Tian, E., & Quinn, R. (2024, July 18). No quick fixes: China’s long-term consumption growth. Rhodium Group. https: //rhg.com/research/no-quick-fixes-chinas-long-term-consumption-growth/

[25]. He, X., & Cao, Y. (2007). Understanding high saving rate in China. China & World Economy, 15(1), 1–13. https: //doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-124X.2007.00049.x

[26]. World Bank. (2023). Households and npishs final consumption expenditure (% of GDP) | data. Data.worldbank.org. https: //data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.CON.PRVT.ZS

Cite this article

Liang,J. (2025). Japan’s “Lost Decades” and China’s Economic Slowdown: Structural Challenges and Policy Lessons. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,223,84-94.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICFTBA 2025 Symposium: Financial Framework's Role in Economics and Management of Human-Centered Development

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. State Street. (2024). China’s future and the echoes of Japan’s lost decades (White paper). State Street Corporation. https: //www.statestreet.com/web/insights/articles/documents/is-china-the-next-japan-whitepaper-final.pdf

[2]. Statistics Bureau. (2024). Statistics bureau home page/population estimates/current population estimates as of october 1, 2024. Stat.go.jp. https: //www.stat.go.jp/english/data/jinsui/2024np/index.html

[3]. Fewsmith, J. (2008). China since Tiananmen: from Deng Xiaoping to Hu Jintao, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

[4]. Gruin, J., & Manchester University Press. (2019). Communists constructing capitalism: State, market, and the party in china's financial reform. Manchester University Press. https: //doi.org/10.7765/9781526135339

[5]. Wang, Y., & Hui, E. C. M. (2017). Are local governments maximizing land revenue? Evidence from China. China Economic Review, 43, 196-215.

[6]. Li, H. (2016). An empirical analysis of the effects of land-transfer revenues on local governments’ spending preferences in China. China (National University of Singapore. East Asian Institute), 14(3), 29-50. https: //doi.org/10.1353/chn.2016.0031

[7]. García-Herrero, A. and J. Xu (2025) 'Will China’s economy follow the same path as Japan’s? ’Policy Brief 09/2025, Bruegel

[8]. Macrotrends. (2009). Nikkei 225 Index - 67 Year Historical Chart. Macrotrends.net. https: //www.macrotrends.net/2593/nikkei-225-index-historical-chart-data

[9]. Noguchi, Y. (1994). Land prices and house prices in Japan. In Y. Noguchi & J. Poterba (Eds.), Housing markets in the U.S. and Japan (pp. 11–28). University of Chicago Press. http: //www.nber.org/chapters/c8819

[10]. Itoh, M., Koike, R., & Shizume, M. (2015). Bank of Japan's Monetary Policy in the 1980s: A View Perceived from Archived and Other Materials (No. 15-E-12). Institute for Monetary and Economic Studies, Bank of Japan.

[11]. Kuttner, K. N., & Posen, A. S. (2001). The great recession: Lessons for macroeconomic policy from japan. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2001(2), 93-160. https: //doi.org/10.1353/eca.2001.0019

[12]. Callen, T., & Ostry, J. D. (Eds.). (2003). Japan’s Lost Decade: Policies for Economic Revival. International Monetary Fund. Chapter: Callen, T., & Nagaoka, T. (2003). Structural reforms, information technology, and medium term growth prospects.

[13]. Wu, F. (2022). Land financialisation and the financing of urban development in china. Land use Policy, 112, 104412. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104412

[14]. Pan, F., Zhang, F., Zhu, S., & Wójcik, D. (2017). Developing by borrowing? Inter-jurisdictional competition, land finance, and local debt accumulation in China. Urban Studies (Edinburgh, Scotland), 54(4), 897-916.

[15]. An, H., Yu, L., & Gupta, R. (2016). Capital inflows and house prices: Aggregate and regional evidence from china. Australian Economic Papers, 55(4), 451-475. https: //doi.org/10.1111/1467-8454.12095

[16]. Alisky, M., Rozelle, S., & Whyte, M. K. (2025). Getting ahead in Today’s china: From optimism to pessimism. The China Journal (Canberra, A.C.T.), 93(1), 1-22. https: //doi.org/10.1086/733178

[17]. Huang, T. (2024). Lessons from China's fiscal policy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper, (24-7).

[18]. Fukunaga, I., Hogen, Y., & Ueno, Y. (2024). Broad-Perspective Review Series Broad Perspective Review Japan’s Economy and Prices over the Past 25 Years: Past Discussions and Recent Issues Bank of Japan Working Paper Series. https: //www.boj.or.jp/en/research/wps_rev/wps_2024/data/wp24e14.pdf

[19]. Alim, A. N., & Leahy, J. (2025, January 10). Falling Chinese bond yields signal concern with deflation. @FinancialTimes; Financial Times. https: //www.ft.com/content/6fe07039-eb7d-47d9-8e97-e933bab0085a

[20]. Tyers, R. (2012). Japanese economic stagnation: Causes and global implications. The Economic Record, 88(283), 517–536. https: //doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4932.2012.00834.x

[21]. The World Bank. (2023). GDP growth (annual %) – China. World Bank. https: //data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?locations=CN

[22]. Latsos, S., & Schnabl, G. (2021). Determinants of Japanese household saving behavior in the low-interest rate environment. The Economists’ Voice, 18(1), 81–99. https: //doi.org/10.1515/ev-2021-0005

[23]. OECD. (2025). OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2025 Issue 1: Tackling uncertainty, reviving growth. OECD Publishing. https: //doi.org/10.1787/83363382-en

[24]. Wright, L., Boullenois, C., Jordan, C. A., Tian, E., & Quinn, R. (2024, July 18). No quick fixes: China’s long-term consumption growth. Rhodium Group. https: //rhg.com/research/no-quick-fixes-chinas-long-term-consumption-growth/

[25]. He, X., & Cao, Y. (2007). Understanding high saving rate in China. China & World Economy, 15(1), 1–13. https: //doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-124X.2007.00049.x

[26]. World Bank. (2023). Households and npishs final consumption expenditure (% of GDP) | data. Data.worldbank.org. https: //data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.CON.PRVT.ZS