1. Introduction

The question of how the Great Recession drove down individuals’ confidence has been frequently reviewed and discussed by scholars over the years. It has been used to interpret the behavior and development of children in the recovery phase, examine its relationship with home ownership, and even check the validity of the confidence index itself [1][2][3]. This essay developed some existing suggestions from the previous writers further, including the distinct types of unemployment and their impacts on confidence, and the collapse of the financial market, with its own brand new insights on the ever-accumulating debts in the US and confidence during this financial crisis. In this paper, with investigations on the causes and how these factors may negatively impact market sentiment over a prolonged period using methods of qualitative research to analyze existing data and gripping the connection between the behavior and following consequences, the author intended to more accurately locate those causes and therefore provide clearer insights to governments and economists in the future on how to properly avoid those issues and the ways to resolve them if encountered. It’s also beneficial for investors in terms of sensing potential indicators that might lead to a decline in the market and therefore helping them to make better financial decisions, especially when facing an impending economic crisis.

2. The Process of the Great Recession and the Collapse of the Financial Market

Since the end of the 20th century, the housing price index in the US has gradually risen, from approximately 80 to 184 in 2006. By the end of Greenspan’s tenure, it rose more than 13% in 2004 and 2005 [4]. During such an increase, a new type of mortgage called subprime mortgage appeared, with the feature of high interest rates and low standards of borrowing. With the securitization of subprime mortgages, investors were allowed to purchase securities backed by the mortgage, providing them with a wider range of funding and steady interest rates [5]. However, due to their lack of transparency and sophisticated nature, it’s hard for credit rating agencies to evaluate the quality of such securities [6]. Many of them were packaged by shadow banks and then sold to investors across the world using wholesale funding. Things went well as housing prices were still rising, as borrowers could sell houses at higher prices even if they couldn’t afford the interest payments. However, this situation was altered by the burst of the housing bubble. Housing prices started to decline in 2006 and continued in early 2007, causing massive defaults on subprime mortgages by low-credit borrowers. Banks, especially shadow banks that held securities involving such mortgages faced tremendous losses as defaults began due to the securitization of subprime mortgages. Some, such as Lehman Brothers, declared bankruptcy on September 15, 2008, spreading panic among the public.

As the Fed and Treasury Department failed to save Lehman Brothers from bankruptcy, investors and banks lost confidence in the loans they held, fearing further default might occur in the future, especially for institutions directly exposed to subprime mortgages. Credit rating agencies like Moody’s also lost their credibility at this point: they failed to distinguish the good securities from the bad ones for the complexity and intransparency of securitized mortgages. Consequently, banks dumped their risky and less-liquid assets promptly even with the risk of putting themselves into insolvency, raising the supply of assets and therefore causing their prices to collapse. Other banks, seeing the prices of assets begin to fall, were urged to sell their assets. This interaction between market mechanisms and banks’ expectations created a vicious downward spiral, automatically imposing downward pressure on prices and forcing institutions to sell assets without examining their quality deliberately, pushing more firms into insolvency. Investors, being afraid that a greater number of institutions would declare bankruptcy as more of them fell into insolvency, tried frantically to get back their cash from the wholesale funding they provided. Even though these short-term funds were ensured by collaterals, investors were unwilling to receive them since the collateral assets were hard to sell in the disrupted market [6]. Similar runs occurred in various parts of the financial market, revealing investors’ confidence loss. The Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped by 777.68 points in one day, the largest point drop in history before the pandemic, and on the day Lehman Brothers declared bankruptcy, it dropped by more than 200 points, indicating a massive firesale conducted by both retail investors and financial institutions as they lost confidence, which further deteriorated the financial condition [7][8].

To ameliorate the financial condition, the Treasury Department and the Federal Reserve convinced Congress to approve an emergency plan to protect banks from bankruptcy. The passing of The Emergency Economic Stabilization Act by Congress in 2008, authorized the Treasury to provide liquidity to financial institutions using up to 700 billion dollars (reduced to 475 billion later) [9]. In total, 991 institutions received payments from the government, with a disbursement of 635 billion dollars, including banks like JP Morgan, AIG, and Bank of America, which were regarded as “too big to fall”. However, though banks were saved from bankruptcy, this approach implemented by the Government had little effect on investors’ confidence in those firms. Take Bank of America Corp, a relatively stable firm, as an example. Its stock reached its peak on October 5, 2007, at 52.71 USD/stock as the economy flourished. However, its stock prices started to plummet significantly after the crisis, and on Feb 27, 2009, the stock value slumped to merely 3.95 USD in a steep slope, showing investors’ low confidence in its credibility. Even when president Bush signed the bailout bill, its stock still indicated a decreasing trend, meaning that investors’ faith in banks was still at an extremely low level even if the government intervened to restore liquidity [10][11].

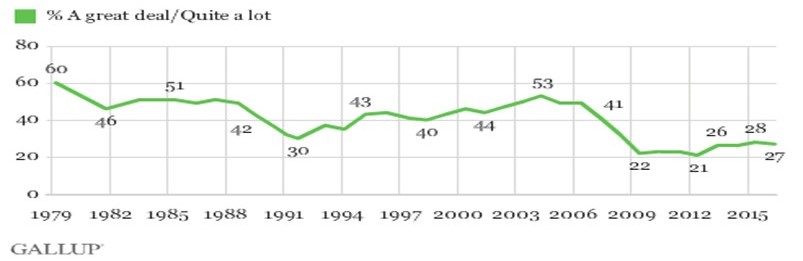

Figure 1: Americans’ confidence in banks, 1979-2016 trends [1].

Such loss in confidence is also reflected in figure 1, with the percentage dropping to 22% in 2009, and remaining below 30% in 2015, indicating that people were less willing to engage in bank activity(borrowing and lending) and gave them fewer credits after the experience of the Great Recession, restricting the banks’ capacity of using the multiplier, and therefore less increase in the percentage of money circulating in the economy. According to the Fisher Equation, MV=PY, this would directly affect the country’s economic growth passively.

3. Unemployment and Confidence

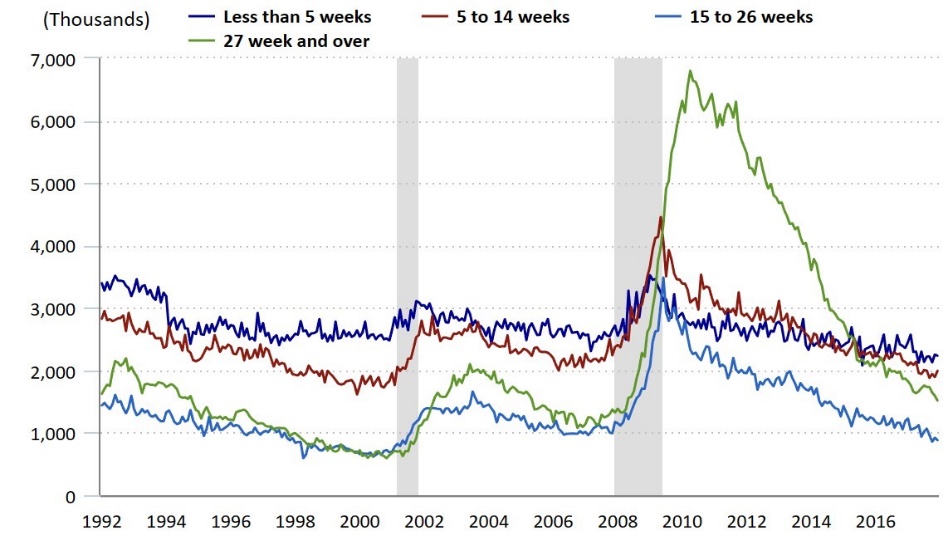

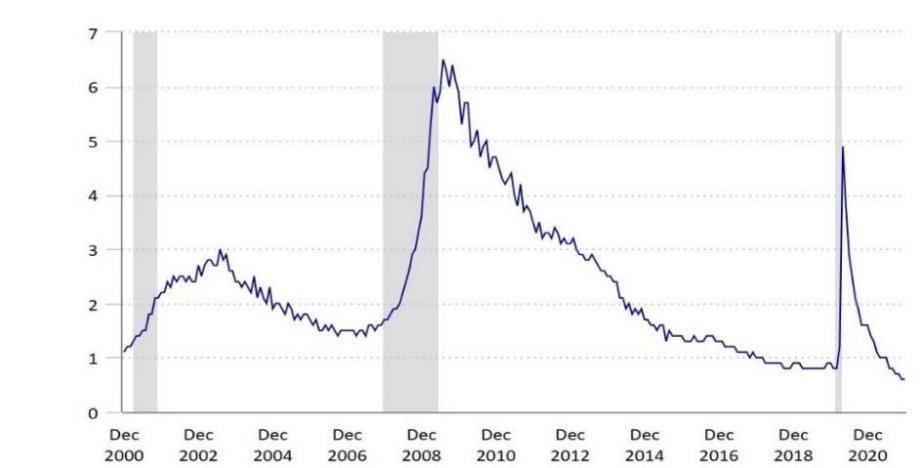

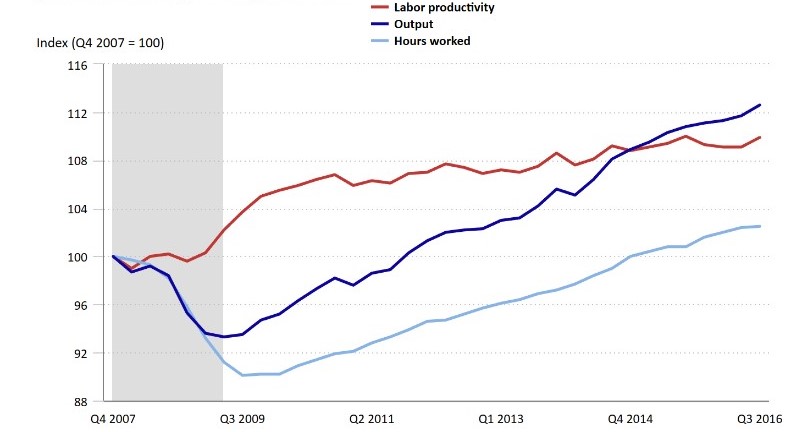

Apart from default and bankruptcy, the rapid rise in unemployment that occurred in the U.S. during the same period also contributed to the loss of confidence. As firms went out of business due to financial reasons, the number of individuals laid off surged. The severity of this rise in unemployment impacted the economy far more significantly than other recessions: As shown in figure 2, the majority of the unemployed people had a duration greater than 27 weeks, and the figure continued to increase after the recession. Not only that, but the number of jobs available was also scarce, increasing the unemployed persons to job opening ratio to a historically high level as illustrated in figure 3, due to the fact that firms were too prudent to expand their businesses, and new firms faced difficulty in entering as borrowing from banks was not that reliable anymore, even with low interest rates. As is typical, the sudden surge in unemployment deteriorated the confidence of staff in active duties, fearing that they might be the next to be made redundant or that the firms they worked for might go bankrupt the next day. This situation referred to the term ergophobia, which is considered a social phobia that produces anxiety that is contagious to others [12]. This phenomenon implied that a minority of employees’ loss of confidence might spread to their colleagues, lowering their efficiency and productivity as they spent too much time dwelling on their job safety, which is supported by figure 4, which shows a fluctuation of around 100 in the labor productivity index, a much lower rate of increase than the following recovery level, and a significant drop in the hours worked and output [13].

Figure 2: Unemployed people, by the duration of unemployment, seasonally adjusted [2].

Figure 3: Ratio of unemployed persons to job opening, total nonfarm, seasonally adjusted [3].

Figure 4: Labor Productivity, output, and hours worked: nonfarm business sector [4].

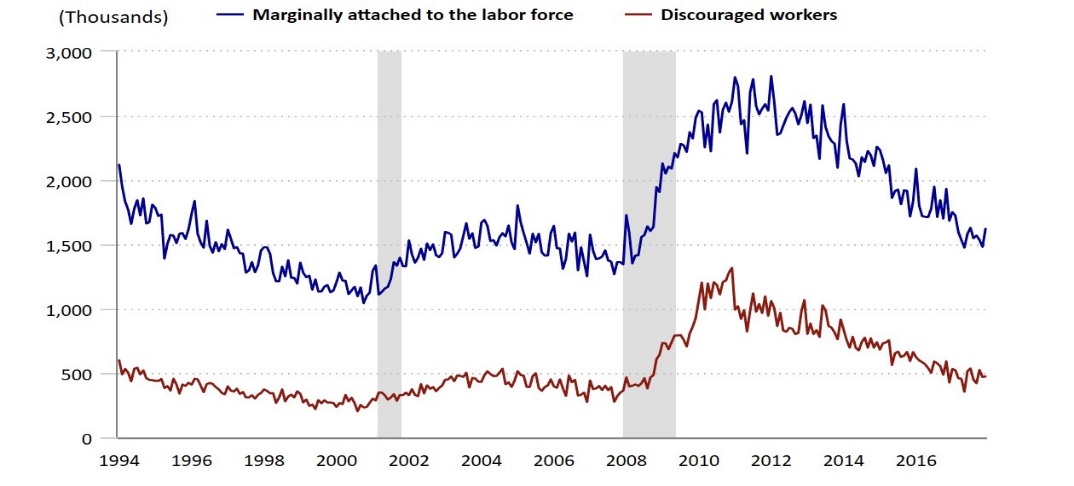

Such a spread in anxiety amount workers and the scarcity of jobs supplied also affected those unemployed workers’ confidence in the labor market, realizing that there were fewer chances for them to be re-employed. Driven by this thought, many of them gave up looking for jobs and became what economists called discouraged workers. In December 2006 in figure 5, there were only 274,000 discouraged workers, and the figure rose to 929,000 in December 2009, reaching its peak in December 2010 with more than 1,300,000 discouraged workers. Further fluctuation in the number of discouraged workers after the recession indicates that citizens were still influenced by the massive unemployment during the Great Recession and therefore more cautious about whether to return to work or not, setting obstacles to the recovery of the United States.

Figure 5: People not in the labor force, not seasonally adjusted [5].

4. Accumulation of Debts

Moreover, although The Emergency Economic Stabilization Act bailed out a range of banks, it also worsened the financial condition of the United States government in terms of debt accumulation. During the financial crisis, the debt-to-GDP ratio soared from 68% to 82% in 2009, with 11,910 billion in total, largely caused by the government’s bailout. According to the Ricardian Equivalence Theorem proposed by David Ricardo, such debt-financed government expenditure may not be helpful in terms of citizens’ confidence, as they came to realize that this increase in debt will be eventually paid by themselves in the form of a rise in taxes in the future. This way of thinking may offset the rise in aggregate demand and economic growth brought by government spending, and this theory was indeed valid to some extent. Several studies conducted in the U.S. have found that every 1 dollar increase in government borrowing would come with a 30 cents increase in private savings, forestalling economic growth as the U.S. keeps building up its debt [14].

This increase in debt also increased the possibility of the U.S. government defaulting on its loans. Due to the large debt accumulation during the Great Recession, the US Congress voted to raise the debt ceiling of the Federal Government on August 2, 2011, allowing its debt ceiling to increase by 400 billion immediately [15]. This action was followed by a downgrade of the credit rating from AAA to AA+ four days after the congressional vote by the well-known credit rating agency S&P, and both Moody’s and Fitch changed their outlook to negative in the same year. This made the U.S. Treasury bonds less attractive to investors as the probability of default rose, which was the biggest advantage of US bonds relative to other countries’ bonds. Being afraid that the US might also default as the amount of debt accumulated was too large to pay back, investors tend to think more carefully about whether to buy its securities or not, especially in today’s financial condition, weakening the borrowing ability of the United State government (Although US Treasury Bonds are still the safest investment in the eyes of the majority of investors).

5. Conclusion

With all those three factors combined, individuals living in the U.S. gradually lost their confidence in financial institutions, the labor market, and the US government itself during the Great Recession, engaging less in economic activities in terms of: 1. lending & borrowing with financial institutions; 2. Job participation; 3. Investment in US Treasuries. These effects were not temporary, instead, the trends continued in the recovery phase, making it harder for the GDP growth rate to maintain the steady and ideal 2%, which was the pre-recession level. It’s the US government’s responsibility to come up with effective recourses to restore confidence within the nation, which would benefit not only the economy of the United States but also the world’s financial health as more people are willing to engage in economic activities. Nevertheless, this paper failed to establish strong connections between 2008’s and current financial conditions, and it also lacked direct solutions to these puzzles. In the future study, the author will focus on constructing more distinct links between these two stages of economic instability and come up with, hopefully, some potential recourses and guidance that could mitigate the passive effects on confidence from the experience of previous recessions.

Acknowledgment

I’d like to express my sincerest gratitude to my economics teachers inside and outside the school and to prominent economists Ben Bernanke and Ray Dalio, the authors of two books I love. They kindled my passion for the study of economics, which spurred me to dive further into the subject and find more joy along the way. There’s no way the accomplishment of this paper could be achieved without their support.

References

[1]. Brooks-Gunn, J., Schneider, W., & Waldfogel, J. The Great Recession and the risk for child maltreatment. Child abuse & neglect, 37(10), 721-729. (2013).

[2]. Bracha, A., & Jamison, J. C. Shifting confidence in home ownership: The great recession. The BE Journal of Macroeconomics, 12(3). (2012).

[3]. Mazurek, J., & Mielcová, E. Is consumer confidence index a suitable predictor of future economic growth? An evidence from the USA. Economics and Management. (2017).

[4]. S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price NSA Index, available at https://www.spglobal.com/spdji/en/indices/indicators/sp-corelogic-case-shiller-us-national-home-price-nsa-index/#data

[5]. Ben S. Bernanke Turmoil in US Credit Markets: Recent Actions Regarding GovernmentSponsored Entities, Investment Banks and Other Financial Institutions: Hearing Before the S. Comm. on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, 110th Cong. (2008)

[6]. Ben S. Bernanke, 21st Century Monetary Policy 61-75

[7]. Kimberly Amadeo, The Stock Market Crash of 2008, available at: https://www.thebalancemoney.com/stock-market-crash-of-2008-3305535#toc-september-2008

[8]. Yahoo! Finance. “Dow Jones Industrial Average (^DJI) - Historical Data.”

[9]. Congressional Research Service “The Emergency Economic Stabilization Act and Current Financial Turmoil: Issues and Analysis,” Pages 2-3. Accessed July 21, 2021.

[10]. Google Finance, available at: https://www.google.com/finance/quote/BAC:NYSE?sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiNp- y8pLj9AhXDD0QIHVoBBnoQ3ecFegQIKhAY&window=MAX

[11]. Temple-Raston, Dina . “Bush signs $700 billion bailout bill” Archived December 2, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. NPR. (October 3, 2008).

[12]. Rodger Dean Duncan, Feeling Anxiety? It’s Contagious, But You Can Choose Not To Be A Spreader, available at:https://www.forbes.com/sites/rodgerdeanduncan/2020/10/27/feeling-anxiety-its-contagious-but-you-can-choose-not-to-be-a-spreader/?sh=7e3af1881006

[13]. Shawn Sprague, Below trend: the U.S. productivity slowdown since the Great Recession, January 2017 | Vol. 6 / No. 2, available at https://www.bls.gov/opub/btn/volume-6/below-trend-the-us-productivity-slowdown-since-the-great-recession.htm

[14]. THE INVESTOPEDIA TEAM, Ricardian Equivalence: Definition, History, and Validity Theories, available at:https://www.investopedia.com/terms/r/ricardianequivalence.asp

[15]. Yeh, Richard; Hamilton, Alec. “Explainer: The Debt Deal – What Happens Next and What’s on the Chopping Block?”. WNYC. Archived from the original on August 7, 2011. (August 3, 2011).

Cite this article

Xia,R. (2023). An Analysis of the Economic Scars of the Great Recession in the United States Through the Lens of Confidence. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,23,26-32.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Management Research and Economic Development

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Brooks-Gunn, J., Schneider, W., & Waldfogel, J. The Great Recession and the risk for child maltreatment. Child abuse & neglect, 37(10), 721-729. (2013).

[2]. Bracha, A., & Jamison, J. C. Shifting confidence in home ownership: The great recession. The BE Journal of Macroeconomics, 12(3). (2012).

[3]. Mazurek, J., & Mielcová, E. Is consumer confidence index a suitable predictor of future economic growth? An evidence from the USA. Economics and Management. (2017).

[4]. S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price NSA Index, available at https://www.spglobal.com/spdji/en/indices/indicators/sp-corelogic-case-shiller-us-national-home-price-nsa-index/#data

[5]. Ben S. Bernanke Turmoil in US Credit Markets: Recent Actions Regarding GovernmentSponsored Entities, Investment Banks and Other Financial Institutions: Hearing Before the S. Comm. on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, 110th Cong. (2008)

[6]. Ben S. Bernanke, 21st Century Monetary Policy 61-75

[7]. Kimberly Amadeo, The Stock Market Crash of 2008, available at: https://www.thebalancemoney.com/stock-market-crash-of-2008-3305535#toc-september-2008

[8]. Yahoo! Finance. “Dow Jones Industrial Average (^DJI) - Historical Data.”

[9]. Congressional Research Service “The Emergency Economic Stabilization Act and Current Financial Turmoil: Issues and Analysis,” Pages 2-3. Accessed July 21, 2021.

[10]. Google Finance, available at: https://www.google.com/finance/quote/BAC:NYSE?sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiNp- y8pLj9AhXDD0QIHVoBBnoQ3ecFegQIKhAY&window=MAX

[11]. Temple-Raston, Dina . “Bush signs $700 billion bailout bill” Archived December 2, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. NPR. (October 3, 2008).

[12]. Rodger Dean Duncan, Feeling Anxiety? It’s Contagious, But You Can Choose Not To Be A Spreader, available at:https://www.forbes.com/sites/rodgerdeanduncan/2020/10/27/feeling-anxiety-its-contagious-but-you-can-choose-not-to-be-a-spreader/?sh=7e3af1881006

[13]. Shawn Sprague, Below trend: the U.S. productivity slowdown since the Great Recession, January 2017 | Vol. 6 / No. 2, available at https://www.bls.gov/opub/btn/volume-6/below-trend-the-us-productivity-slowdown-since-the-great-recession.htm

[14]. THE INVESTOPEDIA TEAM, Ricardian Equivalence: Definition, History, and Validity Theories, available at:https://www.investopedia.com/terms/r/ricardianequivalence.asp

[15]. Yeh, Richard; Hamilton, Alec. “Explainer: The Debt Deal – What Happens Next and What’s on the Chopping Block?”. WNYC. Archived from the original on August 7, 2011. (August 3, 2011).