1. Introduction

The realm of Olympic marketing is a fascinating social and management process that captivates the International Olympic Committee's focus on the grandiose Olympic Games. The exchange of products and values with other enterprises and organizations creates mutually beneficial, long-term relationships - a form of bilateral marketing where both parties actively seek to fulfil each other's needs and complete potential transactions. One notable example of Olympic marketing success is Adidas, whose long history of sponsoring the Olympic Games views it as a long-term investment in its brand image. The company's triumph can be attributed to its strong brand fit, capital, brand advantages, and marketing abilities. By examining the accomplishments of Adidas, we can further comprehend the artistry of Olympic marketing and how it continues to evolve with the Games [1]. Olympic marketing plays a crucial role in the development of the Olympic movement, not only for achieving economic independence through financial support from enterprise groups but also for disseminating the spirit of Olympism worldwide [2]. Its origins date back to ancient Greece, but commercial sponsorship only began to play a significant role in the development of the Olympic Movement during the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games. However, as commercial elements continue to intertwine with the Olympic Games, preventing covert marketing and safeguarding sponsor interests has become a pressing concern [3]. This essay sets out to address this issue by analysing relevant cases and proposing recommendations.

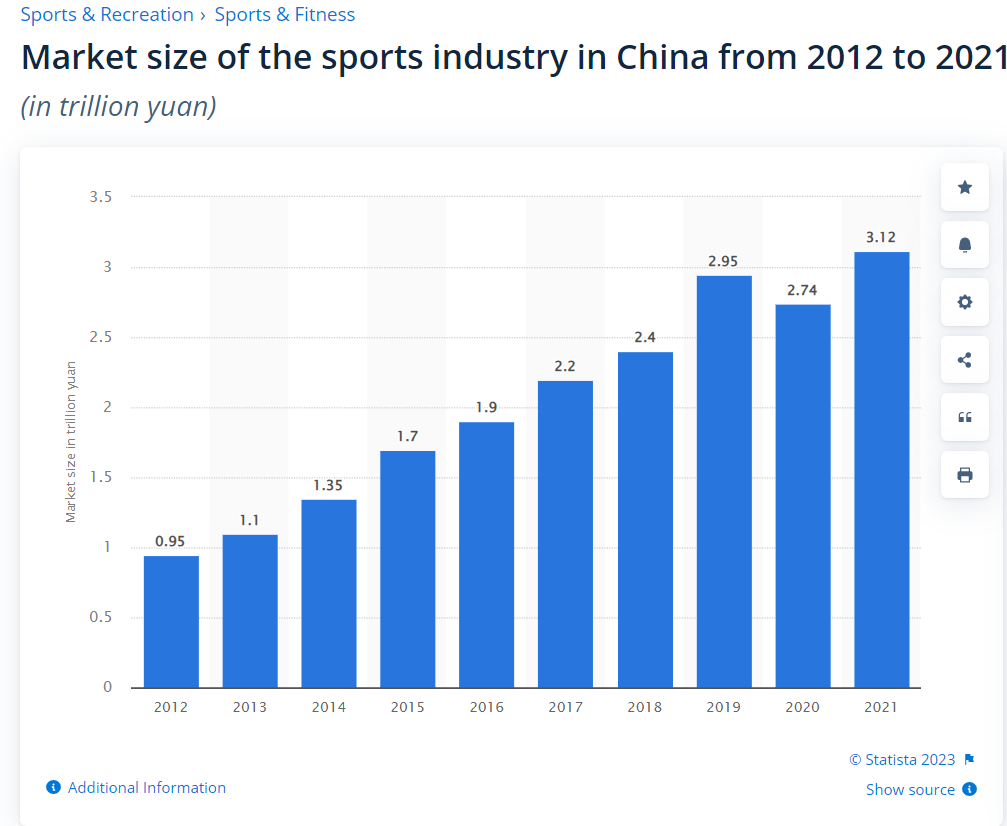

Figure 1: The 2012-2021 Chinese sports industry market size [4].

The sports industry in China attained a market size of 3.12 trillion yuan in 2021. It exhibited consistent growth until 2019, followed by a decline of approximately seven per cent in 2020, owing to the adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 1). So how can Chinese Governments &Enterprises facilitate the sports industry development through joint Marketing& Promotion Efforts? What are the feasible, promising pathways for the Chinese sports industry to boost, activate, and leverage the sports industry as a rising critical part of its national economy drawing on the historic lessons& strategies of the past Olympic events? Can the experiential legacies of the bygone events enlighten the future planning of Chinese sports industry? This essay aims at critically evaluate the empirical heritage of the historic cases and propose strategic suggestions for Chinese governments, enterprises, sports associations, and other stakeholders to participate in and jointly facilitate the sports economy.

2. Economic and Marketing Perspectives: What are the Valuable Lessons & Key Insights from the Past Olympic Events?

The realm of Olympic marketing has seen diverse interpretations among sports economists. Initially, Kelly et al. defined sports economics as the induction of economic methodologies to scrutinize sports [4]. However, scholars Melo et al. propose that sports economics should instead focus on the economics of sports participation, while the specific principles of enterprise economics should be reserved for sports management [5]. Conversely, researchers Bruhn & Rohlmann made a distinct separation between sports economics and sports management. They suggest that sports economics is a more comprehensive and problem-oriented concept that relies on a blend of economic, sociological, and psychological principles to explain the intricacies of sports economics [6]. This dynamic concept is known as sports management on the international level. Moreover, scholar Deninger asserts that sports economics applies theoretical mechanisms of enterprise economics and national economics to every aspect of sports [7]. In contrast, Nagel et al. contend that sports economics is a sub-discipline of economics [8].

As addressed by Blackshaw [10], building, and maintaining long-term relationships with customers, sponsors, and other stakeholders can be decisive to the success of sports games. The theory suggests that relationship marketing can help sports organizations to develop a loyal fan base, increase revenue, and build partnerships with sponsors and other organizations. The Beijing Olympic Organizing Committee values Adidas' expertise and international reach and hopes to leverage it to showcase the charm of the Beijing Olympic Games. Adidas aims to establish brand connections through athletes and product displays, turning passion into a positive brand image and purchase intentions [10]. However, achieving its goal requires continuous improvement, systematic marketing planning, and an understanding of the connotations associated with Olympic marketing. Scholar Winter et al. note that the sports marketing and Olympics marketing strategies in China have been criticized for various shortcomings, including inadequate planning and execution, lack of innovation and creativity, insufficient attention to fan engagement, and a failure to leverage technology [11]. For example, during the Beijing 2008 Olympics, the lack of a coherent brand strategy resulted in missed opportunities to maximize revenue from sponsorship and merchandise sales, while the failure to engage with fans through social media and other digital channels limited the reach and impact of the event. Additionally, Sports marketer Zhang holds that the limited use of data analytics and other technology tools has hindered the ability of Chinese sports organizations to understand and respond to the needs and preferences of their audiences.

Service-Dominant Logic (SDL) is crucial in sports marketing theory, emphasizing the creation of service offerings to generate customer value. [11]. According to SDL, value is created through the co-creation of experiences between the service provider and the customer. In sports marketing, this means focusing on creating engaging experiences for fans that go beyond just the outcome of the game. Historically, the effectiveness of marketing campaigns for the Olympics can have a significant impact on the success of the games. Japan's "United by Emotion" campaign for the 2021 Tokyo Olympics was highly effective in promoting the games despite the challenges posed by the pandemic. By focusing on the theme of unity and emotion, the campaign created a sense of anticipation and reassured people that the event would be safe and well-managed [12]. However, according to the Social Identity Theory proposed by Windari, individuals derive a sense of self from their membership in social groups, and these groups can have a powerful influence on attitudes and behaviour [13]. In the context of sports marketing, this means recognizing the importance of fans' identification with teams and athletes and using this to build loyalty and engagement, that is why successful marketing efforts can leverage national pride and collective spirits for stimulating consumerism. For example, Brazil's "One Year to Go" campaign for the 2016 Rio Olympics was effective in generating excitement and anticipation for the games by showcasing the natural beauty, cultural richness, and enthusiasm for sports in Brazil. The use of the tagline "One Year to Go" created a sense of countdown and anticipation for the games. It is difficult to estimate the direct impact of these campaigns on revenues, but it is likely that they helped attract sponsors and visitors to the games. Overall, these campaigns effectively highlighted the strengths and values of the respective countries and generated excitement and anticipation for the Olympics. Similarly, Canada's "Ice in Our Veins" campaign for the 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Olympics effectively showcased the country's success in winter sports and generated excitement for the games. By highlighting Canadian athletes such as Mark McMorris and Tessa Virtue and emphasizing their dedication and passion, the campaign helped create a sense of national pride and excitement [9]. This was also evident during the 1992 Barcelona Olympic Games when Reebok paid US$2 million to sponsor the US Olympic Committee, but Jordan, the US men's basketball team representative, signed a contract with Nike requiring athletes to exclusively wear Nike's clothing. As a result, some athletes covered the Reebok logo with the American flag during the awards ceremony, reducing Reebok's brand exposure [10].

A theoretical model of brand equity in sports, encompassing brand awareness, brand association, perceived quality, and brand loyalty, was introduced by Mohd et al. [7]. This theory has been used to study the brand equity of various sports entities, such as the National Football League (NFL) and the Olympic Games. The close integration of the Olympic Games and business has led to a proliferation of covert marketing tactics aimed at the Olympic Movement. As addressed by Ennis, covert marketing refers to the intentional or unintentional creation of unauthorized commercial associations with the Olympic Games and the Olympic Movement [8]. Finally, Olympic marketing is a complex undertaking that involves a wide range of sponsors and is difficult to manage. The causes of covert marketing during the Olympic Games include the high sponsorship costs, which are compounded by the significant marketing expenses required during the later stages. Furthermore, the Olympic sponsorship program is typically exclusive, with only one company in each industry being selected as a sponsor. As a result, unsuccessful bidders are left with no option but to resort to implicit marketing strategies to gain promotional opportunities [9].

Martínez introduced a theoretical model of brand equity in sports that comprises brand awareness, brand association, perceived quality, and brand loyalty [6]. This theory has been used to study the brand equity of various sports entities, such as the National Football League (NFL) and the Olympic Games [5]. In enterprise-level marketing, many well-known brands, including Nike, McDonald's, Coca-Cola, and Procter & Gamble, have utilized the Olympic Games as a platform to promote their products and enhance their brand image. Nike has been a long-time sponsor of the Olympic Games and has used the platform to feature Olympic athletes like Serena Williams and Neymar Jr. promoting their products in campaigns such as "Unlimited You" during the 2016 Rio Olympics [4]. McDonald's has also been a sponsor for several years and has used temporary restaurants and free meals for gold medallists in the 2012 London Olympics to promote their brand. Coca-Cola, an Olympic sponsor since 1928, featured Olympic athletes drinking Coca-Cola in their "Taste the Feeling" campaign during the 2016 Rio Olympics. Procter & Gamble, a sponsor since 2010, has launched marketing campaigns such as "Thank You Mom" during the 2016 Rio Olympics, featuring Olympic athletes thanking their moms for their support and sponsoring family lounges for athletes and their families [3]. However, critics argue that the excessive commercialization of the Sports Games through sponsorships undermines the authenticity and spirit of those events. Firstly, some argue that the focus on sponsorships and advertising detracts from the athletic achievements and competition at the core of the games. Host & Moyen point out that the exclusivity of sponsorships can result in the exclusion of smaller, less wealthy companies that could otherwise support the event. Additionally, critics argue that the association of the Olympics with commercial brands can dilute the cultural and national significance of the event, replacing it with a focus on consumerism and global corporate interests [8]. Finally, there is concern that the emphasis on sponsorships can lead to a prioritization of profit over the well-being of athletes and the local community, as seen in the controversies surrounding the construction of Olympic venues and the displacement of residents. Furthermore, intellectual property issues are prevalent in the Olympic Games, particularly in relation to trademarks and copyrights. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) aggressively protects its intellectual property, including the Olympic rings, the Olympic motto, and the Olympic anthem, from unauthorized use by third parties. The IOC also has strict rules on the use of Olympic-related trademarks, logos, and imagery, with severe penalties for infringement. While these measures are intended to prevent unauthorized exploitation of the Olympic brand, they have been criticized for being overly aggressive and restricting legitimate free speech and expression [10]. However, the enforcement of these measures can be difficult, particularly in the digital age where content can be easily shared and disseminated across multiple platforms.

3. Proposition of a Strategic Plans for Stakeholders to Boost the Chinese Sports Industry

Looking forward, China's sports industry ought to further integrate with other industries, encourage healthy lifestyles, and boost domestic demand and consumption, taking advantage of the sector's significant expansion, development environment, and market potential. In October of last year, the country released a development plan for the sports industry that sets the ambitious goal of elevating the country into a foremost sporting power by 2035. The plan outlines eight main targets, including improving mass fitness and making significant strides in the sports industry's development [5]. Beasley et al. proposed a theoretical model of sport consumer behaviour that includes situational factors, personal factors, and marketing factors to design an integrative commercial model of sports events. This theory focuses on studying sports consumer behaviours, such as ticket purchasing, merchandise buying, and media consumption [11]. To boost its sports industry, stakeholders, including the governments, enterprises, and associations can adopt various strategies based on Beasley's theoretical model [12]. Firstly, as addressed by Beasley, situational factors such as the timing and location of sporting events can be leveraged to attract consumers. For example, the Winter Olympics held in Beijing in 2022 have helped to promote winter sports and increase snow tourism revenue in China. Chinese stakeholders can continue to host and promote major sporting events in the country to attract more consumers. Another strategy that Chinese governments can employ is to invest in the construction of Olympic venues and multi-functional development, as demonstrated in the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games. This can help establish a new image of urban tourism, attracting numerous tourists to the hosting cities and promoting the sports industry's development [8]. Secondly, personal factors such as the values, attitudes, and behaviours of sports consumers can be considered. Chinese stakeholders can tailor their marketing efforts to appeal to these factors [9]. For example, governments can promote the health benefits of participating in sports and encourage a culture of physical fitness and exercise among the population. Furthermore, enterprises and unions can take advantage of the impact of sports tourism enthusiasts who watch the Olympic Games, purchase Olympic souvenirs, and participate in related entertainment activities. By developing Olympic publicity activities such as the "Olympic Glory Plan" and "National Fitness Plan," the number of people engaging in sports and leisure tourism can continue to increase. Lastly, marketing factors such as sponsorship deals can be used to boost the sports industry in China. One strategy that Chinese stakeholders can adopt is to combine urban promotion with active and comprehensive marketing for industries related to sports tourism [7]. This can help to achieve long-term and sustainable effects, attracting domestic and foreign tourists to the region, and promoting the development of the sports industry. However, the effectiveness of sponsorship depends on the brand exposure gained. As seen in the case of Reebok during the 1992 Barcelona Olympics, sponsoring the Olympic Committee may not serve functions as sponsoring individual athletes, teams, or TV stations. Therefore, Chinese stakeholders should carefully evaluate their sponsorship opportunities and choose those that offer the greatest brand exposure and return on investment.

However, the current Olympic business model and marketing strategies can contribute to the fierce contest among industry rivals for public attention and social exposure, and this competition is increasingly hinged on resources including networks, social connections, and financial strengths. Resource dependence theory suggests that organizations are dependent on external resources, such as funding and support, to achieve their goals. In sports marketing, this theory is used to understand the relationships between sports entities and their stakeholders, such as sponsors, media, and fans [5]. Rodríguez et al. proposed a theoretical model of resource dependence in sports that includes resource acquisition, resource allocation, and resource utilization. This theory has been used to study the resource dependence of various sports entities, such as collegiate athletic departments and professional sports franchises [3]. For example, in 2008, Li Ning lost the right to sponsor the Chinese delegation's award uniform to Adidas due to competitors’ high sponsorship fees, but instead signed a cooperation agreement with CCTV Sports Channel for host and reporter clothing. This resulted in Li Ning gaining significant brand exposure during the Olympic Games through media coverage. During the 2012 London Olympic Games, Nike, a non-Olympic sponsor, released a marketing campaign called "Live Your Greatness" and included misleading references to East London in South Africa, Little London in Jamaica, and London, Ohio, which led to 37% of American consumers believing Nike was the official sponsor of the games, while only 24% correctly identified Adidas. These issues highlight how sponsorship and intellectual property issues can undermine the authenticity and spirit of the Olympic Games [7]. Given the above deficiencies, Chinese sports associations, such as the Chinese Football Association and the Chinese Basketball Association, can partner with local governments to develop new sports facilities and infrastructure. For example, they can work with city governments to build new stadiums and training facilities for their respective sports. Hallmann & Petry suggest that Chinese brands, such as Li-Ning and Anta, can partner with sports associations and athletes to promote their products [11]. For example, Li-Ning has a long-standing partnership with the Chinese Gymnastics Association, while Anta has partnered with the Chinese Tennis Association and several NBA players [12]. Chinese brands can also invest in sports marketing to promote their products and increase brand awareness. Specifically, in the lead-up to the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics, several Chinese brands, including Alibaba, Tencent, and China Mobile, have signed sponsorship deals with the International Olympic Committee.

4. Conclusion

To conclude, various economic methodologies have been proposed for analyzing sports, establishing lasting stakeholder relationships, and generating customer value in Olympic marketing. Effective strategies can leverage national pride and social identity to encourage consumerism [8]. A theoretical model of sports brand equity has been introduced. China aims to become a sports power by 2035 through integrating sports industry with other sectors, promoting healthy lifestyles, and domestic consumption. To achieve this goal, stakeholders can leverage situational, personal, and marketing factors. However, fierce competition and authenticity issues can result from the current Olympic business model and marketing strategies [5]. Chinese sports associations and brands can partner with local governments, invest in sports marketing, and develop new infrastructure and facilities to increase brand awareness. By hosting international sports events, Chinese stakeholders can showcase their sports facilities, attract international visitors, and boost the local economy.

References

[1]. Coombs, W. T., & Harker, J. L., Strategic sport communication traditional and transmedia strategies for a global sports market. Routledge (2021).

[2]. Cornwell, T. B., Sponsorship in marketing: effective partnerships in sports, arts, and events (2nd edition.). Routledge (2020).

[3]. Alonso Dos Santos, M., Alonso Dos Santos, M., Calabuig Moreno, F., Valantine, I., & Calabuig Moreno, F., The Management of Emotions in Sports Organizations. Frontiers Media SA (2020).

[4]. Statista.com Homepage, https://www.statista.com/., last accessed 2023/02/01.

[5]. Melo, R., Sobry, C., & Van Rheenen, D., Small scale sport tourism events and local sustainable development: a cross-national comparative perspective (R. Melo, C. Sobry, & D. Van Rheenen, Eds.). Springer (2021).

[6]. Bruhn, M., & Rohlmann, P., Sports marketing: fundamentals - strategies - instruments. Springer (2023).

[7]. ResearchGate.com homepage, https://www.researchgate.net/., last accessed 2023/2/2.

[8]. Nagel, S., Elmose-Østerlund, K., Ibsen, B., & Scheerder, J., Functions of sports clubs in European societies: a cross-national comparative study (S. Nagel, K. Elmose-Østerlund, B. Ibsen, & J. Scheerder, Eds.). Springer (2020).

[9]. TechTarget.com homepage, https://www.techtarget.com/., last accessed 2023/02/02.

[10]. Blackshaw, I. S., Sports Marketing Agreements: Legal, Fiscal and Practical Aspects. T.M.C. Asser Press (2012).

[11]. Zhang, J. J., & Pitts, B. G., International sport business management: issues and new ideas (J. J. Zhang & B. G. Pitts, Eds.). Routledge (2021).

[12]. Zheng, J., & Mason, D. S., Brand Platform in the Professional Sport Industry: Sustaining Growth through Innovation (1st ed. 2018.).

[13]. Martínez, J.A., The paradoxical marketing of sports equipment brands. Revista internacional de ciencias del deporte, 10(35), pp.1–3(2014).

[14]. Rodríguez, P., Késenne, S. and Koning, R., The economics of competitive sports. P. Rodríguez, S. Késenne, & R. Koning, eds. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing (2015).

Cite this article

Zhang,H. (2023). The Guiding Significance of Olympic Marketing on China's Sports Industry Business Promotion: What are the Enlightenment and Lessons from Historic Cases?. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,25,30-36.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Management Research and Economic Development

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Coombs, W. T., & Harker, J. L., Strategic sport communication traditional and transmedia strategies for a global sports market. Routledge (2021).

[2]. Cornwell, T. B., Sponsorship in marketing: effective partnerships in sports, arts, and events (2nd edition.). Routledge (2020).

[3]. Alonso Dos Santos, M., Alonso Dos Santos, M., Calabuig Moreno, F., Valantine, I., & Calabuig Moreno, F., The Management of Emotions in Sports Organizations. Frontiers Media SA (2020).

[4]. Statista.com Homepage, https://www.statista.com/., last accessed 2023/02/01.

[5]. Melo, R., Sobry, C., & Van Rheenen, D., Small scale sport tourism events and local sustainable development: a cross-national comparative perspective (R. Melo, C. Sobry, & D. Van Rheenen, Eds.). Springer (2021).

[6]. Bruhn, M., & Rohlmann, P., Sports marketing: fundamentals - strategies - instruments. Springer (2023).

[7]. ResearchGate.com homepage, https://www.researchgate.net/., last accessed 2023/2/2.

[8]. Nagel, S., Elmose-Østerlund, K., Ibsen, B., & Scheerder, J., Functions of sports clubs in European societies: a cross-national comparative study (S. Nagel, K. Elmose-Østerlund, B. Ibsen, & J. Scheerder, Eds.). Springer (2020).

[9]. TechTarget.com homepage, https://www.techtarget.com/., last accessed 2023/02/02.

[10]. Blackshaw, I. S., Sports Marketing Agreements: Legal, Fiscal and Practical Aspects. T.M.C. Asser Press (2012).

[11]. Zhang, J. J., & Pitts, B. G., International sport business management: issues and new ideas (J. J. Zhang & B. G. Pitts, Eds.). Routledge (2021).

[12]. Zheng, J., & Mason, D. S., Brand Platform in the Professional Sport Industry: Sustaining Growth through Innovation (1st ed. 2018.).

[13]. Martínez, J.A., The paradoxical marketing of sports equipment brands. Revista internacional de ciencias del deporte, 10(35), pp.1–3(2014).

[14]. Rodríguez, P., Késenne, S. and Koning, R., The economics of competitive sports. P. Rodríguez, S. Késenne, & R. Koning, eds. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing (2015).