1.Introduction

Despite the fact that COVID-19 decreased the food deliveries, there were still more than 400,000 deliveries per day in Beijing alone during the pandemic [1]. Gig economy is defined as “the exchange of labour for money between individuals [independent workers] or companies via digital platforms that actively facilitate matching between providers and customers, on a short-term and payment by task basis” [2]. On March 21st, 2020, a Chinese delivery man named Mr. Gao was put on the front page of TIME magazine under a heading describing delivery workers in heroic terms. Under lockdown, more than 6 million food delivery workers helped to distribute medicine, daily supplies, and meals, becoming the crucial link between individual households and society [3]. Despite the convenience and prevalence of the gig economy, it is not void of criticisms from the scholarly community.

After the establishment of the sharing economy around the world, the debate of whether its advantages outweigh its disadvantages has always been at the center of scholarly attention. However, both sides have long been seeking a feasible proposal to address the shortcomings of the gig economy. This pandemic seems to be an excellent catalyst for some positive change in the industry: as the media portrayed Chinese delivery workers as the heroes of the society, people might realize the poor living standard of those workers and thus demand change. Therefore, this paper primarily focuses on two big Chinese food delivery platforms: Meituan and Elem.me, and explores the impact of the pandemic on the living standards of the Chinese delivery workers.

2.Literature Review

Categorized as a gig economy, the Chinese food delivery industry first started when university students began ordering online because the food deliveries were often more delectable and convenient than cafeteria food. Growth in online deliveries fueled a need for delivery workers in urban areas, which created the need for the first delivery companies [4]. Since 2009, with the rapid development of the internet and e-commerce in China, the industry has grown rapidly. It has grown by 142.2 billion yuan ($20B USD) between 2018 and 2019, an increase of 30% [5]. With this rapid growth, meal deliveries have become an integral part of people’s lives: in 2019, consumers of the food delivery industry reached 460 million. With the Chinese public’s ever-growing appetite for convenient and affordable delivery meals, two main players, the ordering-and-delivery platforms Ele.me and Meituan, began competing for faster delivery, cheaper prices, and better service [4]. In order to provide faster service, both companies hired more delivery workers. For example, Meituan alone had 2.95 million delivery workers in 2020 [5]. Although the food delivery industry provided a significant amount of job opportunities to the Chinese economy, the living conditions of those delivery workers are still in question.

Before the pandemic, the Chinese food delivery workers experience some challenges common to the gig economy, but also have their unique challenges. In the existing literature, there are three main problems Chinese delivery workers face: inequality, emotional labour, and time constraints.

In terms of inequality between the consumers and workers, Sun confirmed that customers can unreasonably and negatively impact Chinese delivery workers’ salaries [6]. Previous studies on Uber also concluded that the rating system can mask online discrimination [7]. This means that the customers can unjustifiably rate their drivers because of their colour or background. In China, Sun didn’t find cases of race discrimination, but she found customers are entitled to “cancel the order” or “rush the food” at any time during the ordering process [6]. Customers can make last-minute decisions and rush the delivery workers, thus adding a significant amount of stress to the delivery workers. Furthermore, Sun found that from a platform perspective, a customer is more valuable than a worker because delivery workers are “regarded as highly replaceable”, so they don’t have a lot of bargaining when it comes to complaints [6]. The inequality in Chinese food delivery platforms exists in the forms where customers have the unproportional power to cancel their orders on a whim, require the workers to deliver faster, and have more influence in disputes.

Second, the concept of “emotional labour” was first defined as “labour requires one to induce or suppress feeling in order to sustain the outward countenance that produces the proper state of mind in others” [8]. Emotional labour refers to the psychological effort that allows employees to act happy even when they don’t really feel happy. This concept of emotional labour has been discovered widely in the gig economy. For example, Uber drivers usually need to perform small talk in hopes to receive a good rating [9]. Similarly in China, many interviewees from Sun’s study mention that they had to “consistently make phone calls, set times, and wait outdoors when a customer was not home”. Moreover, they sometimes were required to apologize even if they were not responsible for the delay [6]. Therefore, Chinese delivery workers need to perform various emotional labour.

As the online food delivery platforms cater to customers’ immediate needs, delivery workers in China are usually under great pressure to deliver orders to customers within time constraints [4]. Sun found that the AI system shortens the delivery time to optimize workers’ efficiency. And failing to meet the time requirement would result in a deduction in the pay of the worker [6]. The delivery systems’ estimated time function does not account for traffic or accidents, and, as such, often results in a significant income reduction for the delivery workers while increasing the risk of traffic accidents [6]. During the first half of 2019, in Shanghai alone, there were two deaths and over 220 injuries related to deliveries by Meituan and Ele.me [9]. By punishing the workers for not delivering under shorter and shorter time constraints, the companies are endangering delivery workers' lives and continue to make the job more stressful.

However, the pandemic presents a unique opportunity to bring public attention to the struggle of the delivery workers. They were recognized by multiple media to be the heroes supplying households with essential goods [10]. Even though platforms do not force delivery people to deliver to hospitals, many riders volunteered to deliver hot meals to the healthcare workers [11]. Some of them didn’t disclose their locations with their families, who certainly worried about their safety [11-12]. Because of the delivery workers, fewer citizens needed to go to stores to buy groceries, thus helping curb the spread of Coronavirus. Recognized as heroes, the government invited a Meituan delivery worker to the press conference held by the State Council Information Office [13].

In the existing literature, there is a debate whether the media have an impact on public perception of the particular population described by the media. Happier and Philo found that there is a relationship between negative media coverage of people on disability benefits and a hardening of attitudes towards them [14]. The result of this study shows that people’s perceptions can be influenced by news media. However, Hammond argued that the correlation between media and public perception may not be significant by analyzing a social movement in Mexico called the Landless Workers’ Movement (Movimento dos Trabalhadores Sem Terra, MST). Despite overwhelmingly negative media portrayals of the MST, it still won significant public support and maintained a high level of mobilization [15]. This study shows people’s perception is subject to more factors than news coverage, such as one’s experience, knowledge, and family.

As more people rely on gig work as their primary occupation, the challenges discussed in the literature review are becoming more pressing. In light of the positive media attention and the heightened importance of food delivery workers in China, there is no research on how this media attention can impact some of those problems that delivery workers experienced. Furthermore, there is no literature that examines the lives of Chinese delivery workers during the recent pandemic. Therefore, this research paper seeks to fill two gaps: the extent to which an unprecedented event can impact the working conditions of the gig workers in an economy, and the impact of media attitude on the gig economy. So, the researcher seeks to answer the following question: given the abundance of positive media and public attention, what’s the real impact of COVID-19 on the standard of living of Chinese food delivery workers in the gig economy? Other than delivering the food to their destination, and those tasks involve significant emotional labour which worsens their level of stress.

3.Analysis of the Impact of the Pandemic on Chinese Food Delivery Workers

3.1. Worker’s Compensation

From a micro-level for each individual worker, the researcher theorizes we are likely to see a decrease in average wages, because of increased labour supply for delivery workers and a net negative shift in demand for food deliveries. Meituan recruited an additional 336,000 workers during the pandemic, while Ele.me recruited 142,000 workers [16]. Therefore, the labour supply for food delivery workers increases during the pandemic. Secondly, the food delivery industry may suffer a negative shift in demand during the pandemic. In February 2020, despite the surge in order during the spring festival, the total online food orders still were considerably less than that of the pre-pandemic time [1]. As people are staying home under lock-down, there may be more inclined to cook themselves because they have more time and want to avoid the potential risk of infections. Although we may see a small increase in demand for grocery deliveries, the magnitude of such demand may not be enough to offset the negative shock to the demand. Thus, we have a large possibility of seeing a decline in workers’ wages, because they receive payments based on the number of orders they delivered.

3.2 Customer Satisfaction and Delivery Speed

Firstly, we would expect the delivery time to be shorter during the pandemic. As most restaurants don’t provide dine-in services, online deliveries became restaurants’ only priority during the pandemic. However, it is also a possibility that restaurants laid off more workers to achieve more cost efficiency, which may make the decrease in preparation timeless significant. Overall, we should still expect a shorter preparation time for the restaurants as there were fewer food orders made during the pandemic as mentioned in the previous section.

Secondly, we would expect customers to have a more flexible schedule and thus have fewer expectations during the pandemic. Before the pandemic, orders made between 11 am-1 pm made up for 26.3% of all orders made in a day [17]. Supporting these statistics, Liu and Flowski suggested that this may be because many customers may have an exact time for their lunch break [4]. However, during the pandemic, as customers have a more flexible schedule that doesn't require them to finish lunch at an exact time, they may order in different time periods and are less likely to give delivery workers a bad rating when they fail to deliver within the time limit.

From ratings that delivery workers receive, we can gain a better understanding of customer experiences during the pandemic. Potentially due to faster delivery speed and more flexible schedules, the customer may be more inclined to give better ratings to the delivery workers.

3.3 Social Recognition and Respect

Lastly, this research paper is going to look at delivery workers’ social status and respect from a macro perspective. During the pandemic, food delivery workers are most likely going to experience an improvement in both areas because of the positive media attention and improvements in rating. Firstly, as mentioned in the literature review, the media portrayed delivery workers as heroes [13]. Realizing that, customers should be more inclined to treat them with more respect. As a result, delivery workers should feel an improvement in their social status.

As mentioned in the section above, food delivery workers’ rating is expected to increase during the pandemic. Suggested by the self-consistency theory, individuals attempt to maintain consistency between their self-concept and performance [18]. Thus, if a better rating acts as a sign of their work performance improvements, the delivery workers are more likely to perceive an improvement in their social status.

4.Empirical Research

4.1 Method

The researcher adopted a mixed-method approach. The first part involves qualitative research using interviews, and the second part involves quantitative research using online surveys.

The researcher conducted 11 online semi-structured interviews via Wechat, a popular Chinese social media platform. The researcher prepared a total of nine structured questions that were designed to understand delivery men's experiences during the pandemic. Interviews allowed the researcher to record many personal stories and ask follow-up questions to understand the rationale behind their answers. By analyzing interview data, the researcher explored insights into the community of Chinese delivery workers in the particular context of COVID-19.

Verbal informed consent was obtained from participants before the interview. The duration of the interviews was from 20-60 minutes. In each interview, the author began by telling the workers the purpose of the study and ensuring them that the interview data would be confidential. All interviews were conducted in Chinese and then translated into English by the author, who is fluent in both languages.

After interviewing eleven delivery workers, the author although interviews provided the researcher with insightful personal stories, they were not enough to represent most delivery workers. Therefore, the author sent out Tencent survey link to delivery workers’ Wechat groups and also asked them to share it with their co-workers. The author designed a five to ten-minute survey consisting of closed format questions where the respondent had to choose from a set of given answers. The online survey was administered between August 28th to September 28th, 2020. The researcher received a total of 227 responses (168 male, 59 female, 103 full-time, and 124 part-time). With this more representative sample, the researcher used technology to analyze the data with the Chi-squared goodness of fit test and produced detailed infographics. When analyzing the quantitative data, the researcher referenced the interview data to provide specific stories to help explain the reasons behind the distribution.

4.2 Survey Results

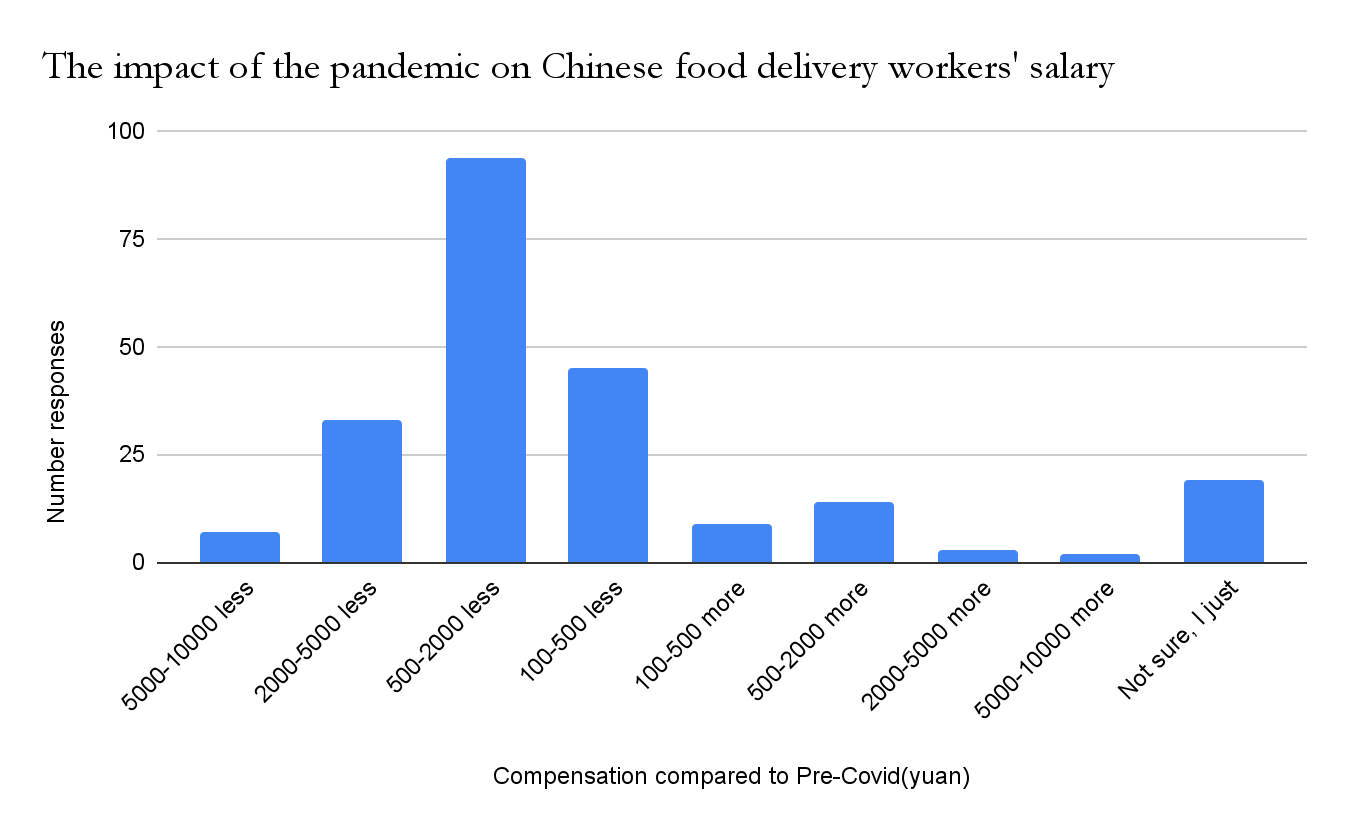

Fig. 1. The impact of the pandemic on Chinese food delivery workers’ salary.

Out of 227 responses, 76.2% of the respondents replied that their monthly income during the pandemic decreased, with 41.4% receiving 500-2000 yuan (71.4 - 285.7 USD) less and 20.3% 100-500 yuan (14.28 -71.4 USD) less. Only 12.4% reported an increase in income during the pandemic. This graph shows strong evidence that delivery workers suffered a significant income loss during the pandemic. After performing a chi-square test, we received a p-value of 1.18 x 10^-25, which is small as well. If the pandemic made no change to the worker’s wages, it is statistically impossible to gather this set of results by chance alone.

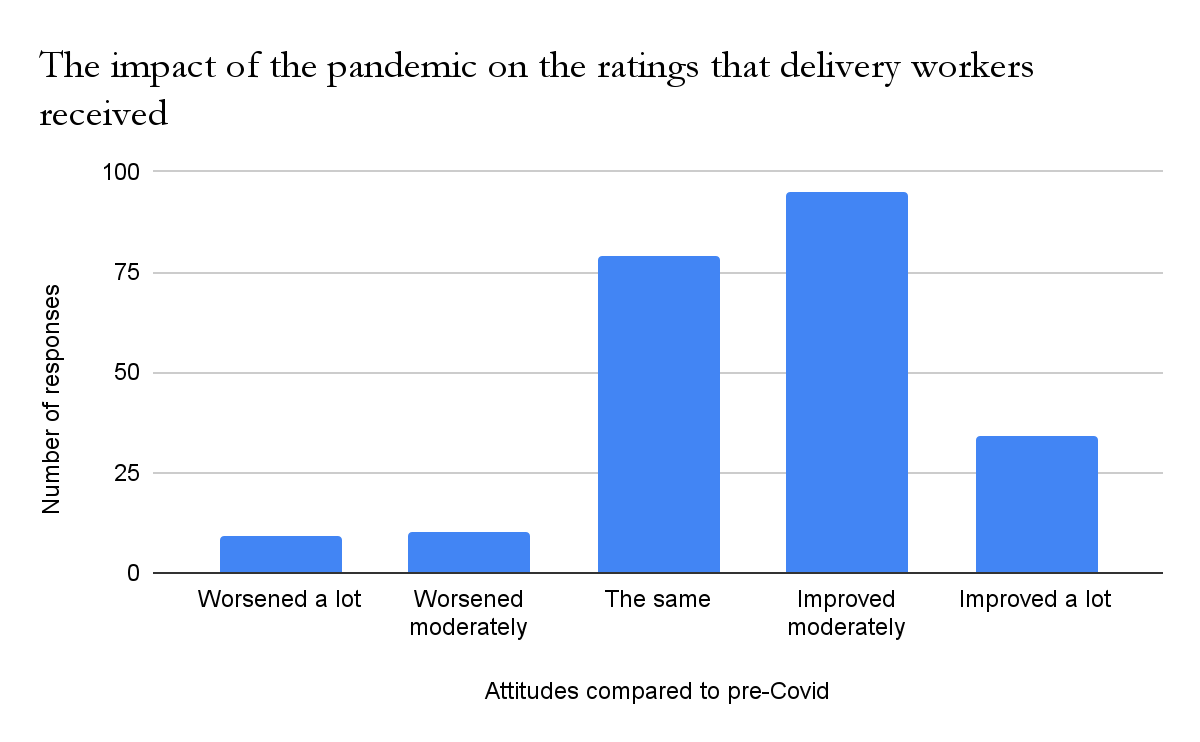

Fig. 2. The impact of the pandemic on the ratings that delivery workers received.

8.4% of the respondents replied that their ratings worsened during the pandemic. 34.8% of the respondents believed that their ratings remained the same. While 56.9% of respondents reported a positive impact on their ratings, 41.9% feel their ratings improved moderately. 15% felt their ratings improved a lot during the pandemic. This suggests that there might be significant improvements in workers’ ratings during the pandemic. After performing a chi-square test, we received a p-value of 3.89 x 10^-18, which is small as well. If the pandemic made no change to the worker’s ratings, it is statistically impossible to gather this set of results by chance alone.

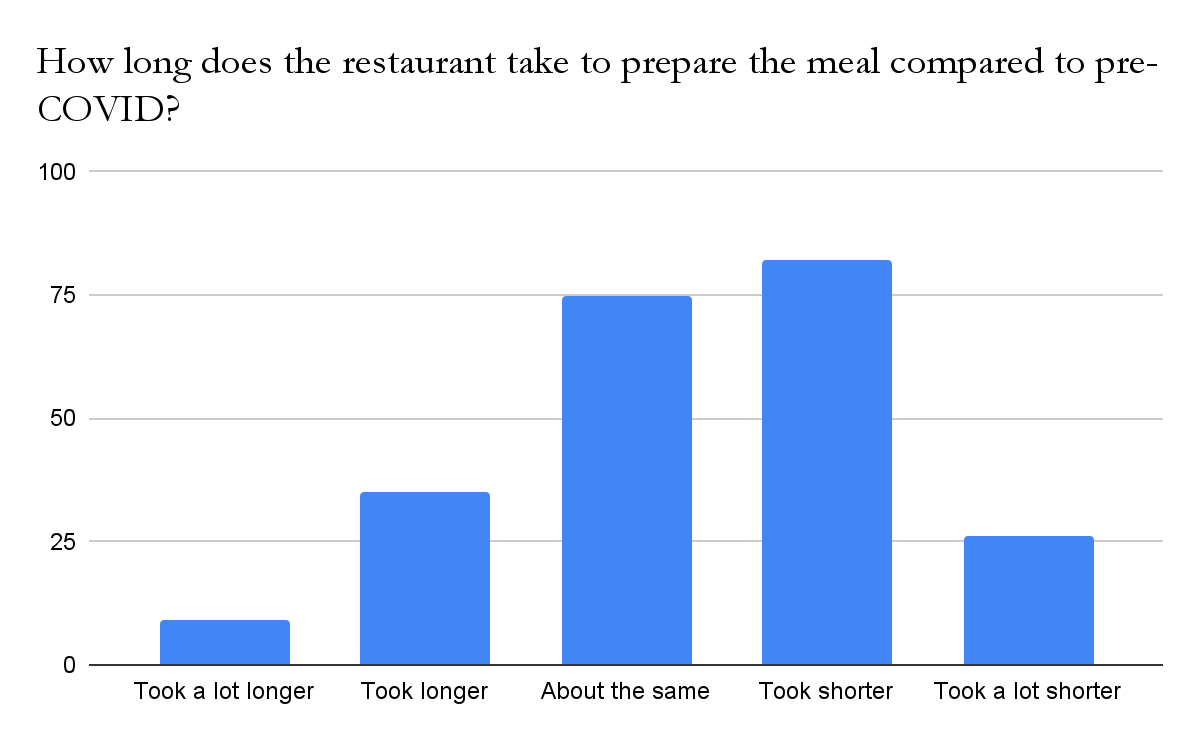

Fig. 3. How long does the restaurant take to prepare the meal compared to pre-pandemic.

19.4% of the respondents replied that the restaurants took more time during the pandemic, with 4% believing that the time was a lot longer and 15.4% believing that it took moderately longer. 33% of the respondents believed that the restaurants took around the same time before and during the pandemic. 47.6% of respondents reported the restaurants took a shorter time to prepare: 36.1% felt it was shorter and 11.5% reported that it was a lot shorter. This shows that there might be a moderate decrease in the time needed for restaurants to make food. After performing a chi-square test, we received a p-value of 1.32 x 10^-6, which is small. If the pandemic made no change to the time it takes for restaurants to prepare food, it is statistically impossible to gather this set of results by chance alone.

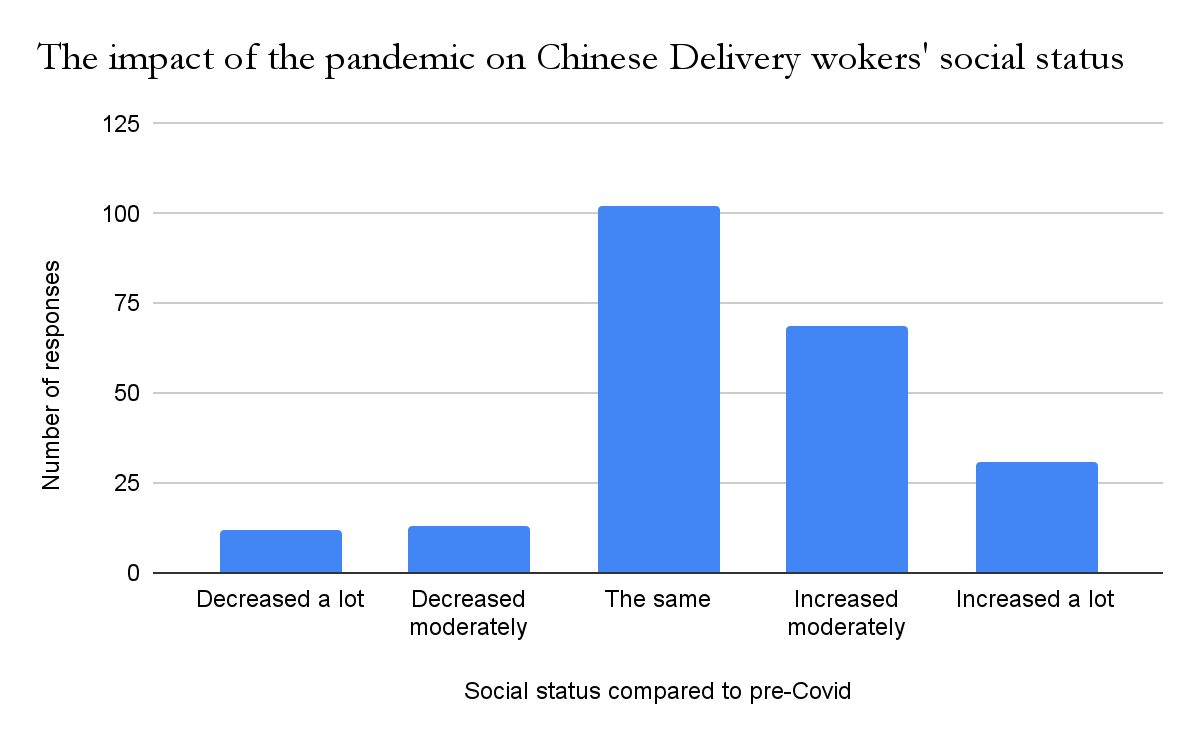

Fig. 4. The impact of the pandemic on Chinese food delivery workers’ social status.

11.1% of the respondents replied that they sensed a decrease in their social status during the pandemic. 45.10% of the respondents believed that their social status remained the same. While 43.8% of respondents sensed a positive impact on their social status during the pandemic, 30.50% felt their social status has increased moderately. 13.3% felt their social status increased a lot during the pandemic. It is reasonable to suggest that there may be a moderate improvement in Chinese delivery workers' social status during the pandemic. After performing a chi-square test, we received a p-value of 8.79 x 10^-12, which is incredibly small. This p-value means that if the pandemic hadn’t changed Chinese delivery workers’ social status at all, it is statistically impossible to receive this set of survey results by chance alone.

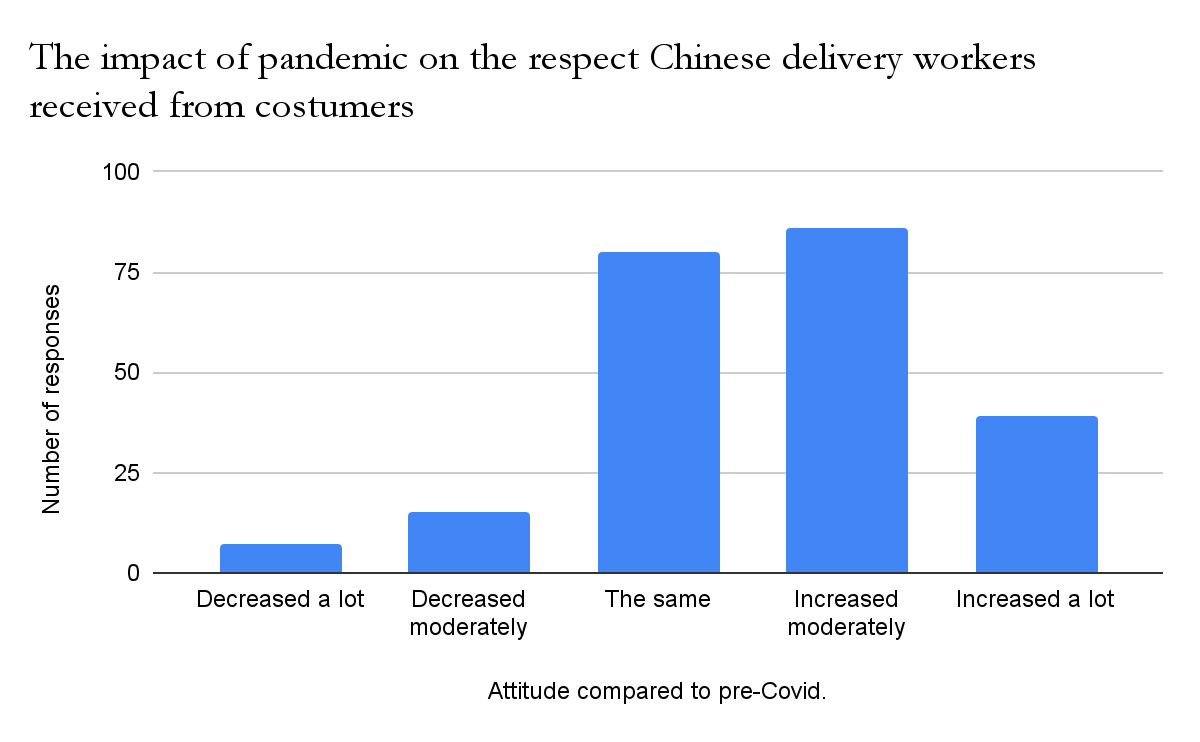

Fig. 5. The impact of the pandemic on the respect that Chinese food delivery workers received from costumers.

9.7% of the respondents replied that they sensed less respect from customers during the pandemic. 35.40% of the respondents sensed no significant shift in customer attitude. While 54.9% of respondents sensed a positive change during their interaction with their customers during the pandemic, 38.10% felt consumers’ attitudes improved moderately, 16.8% felt it improved a lot during the pandemic. This suggests that there might be significant improvements in the workers/customer relationship. After performing a chi-square test, we received a p-value of 4.97 x 10^-16, which is incredibly small. If the pandemic made no change to the relationship between the workers and the consumers, it is statistically impossible to receive this set of results by chance alone.

4.3 Interview Summary

Besides two interviewees who recently became delivery workers, nine interviewees all said that they earned less money during the pandemic. They confirmed that they received significantly fewer orders during the pandemic because many people were concerned about the risk of infection. As more people were staying home instead of going to work, the demand for delivered meals decreased dramatically. One interviewee, Mr. Liu summarized the situation:

“I got fewer orders because people were staying at their house. So there were fewer white-collar workers regularly ordering delivery. And a lot of public places were closing down as well, such as bars. Worse, more people became delivery men and we were all competing for limited orders.”

As his job at a tourism site in Inner Mongolia was no longer available, Mr. Hao became a delivery worker during the pandemic. He said he earned roughly the same amount as his previous job. When asked about his biggest motivation, he replied: “Money. The more I work, the more I get. It’s all transparent. I get 9 yuan per ride. ” Mr. Xu was another interviewee who became a full-time food delivery worker during the pandemic. After his restaurant closed down during the pandemic, he signed up for Meituan full-time. He said that he had to work harder now, but he also earned slightly more as a delivery man. Even though he still had to stick to a working schedule, he appreciated that he didn’t have a manager who constantly looked over his shoulder. In fact, this job provides an ideal vision that shows that if you work hard enough, you can earn up to 10,000 yuan (US$1400) per month regardless of your education level. As the pandemic closed down more businesses and laid off many low-skilled workers, delivery workers became an attractive profession. Particularly, Mr. Hao and Mr. Xu represented the perspective of newly joined delivery workers. In conclusion, as a result of fewer orderings and increased labour supply, interviewees who worked as food delivery workers reported a decrease in income.

Talking about their ratings, all interviewees reported either positive or no change in the number of positive ratings they received. The ones who expressed a neutral opinion said they didn’t have a lot of bad ratings in the beginning. Among those who experienced an improvement in ratings, some suspect that it may be partially due to the shortened meal preparation time by the restaurants. When workers had many orders at the same time, they could be easily punished for overtime orders because of various unpredictable factors. For example, if a delivery man had ten orders to deliver and the first restaurant took longer than expected to prepare the food, it could cause a domino effect, forcing the worker to go overtime on all the rest of his orders, which potentially resulted in lower ratings and even docked pay. One interviewee, Mr. Shi, explained the system and its flaws thoroughly:

“In terms of the time limit, workers can report the restaurant if it takes too long, and the system will give him 7 minutes on that order. Workers can extend a total of 14 additional minutes if the restaurant takes longer than usual before they can file a complaint to the restaurant. However, it may cause a domino effect, causing delivery men to go overtime on other orders.”

Fortunately, seven interviewees expressed that as restaurants didn’t have eat-ins during the pandemic, they usually take less time to prepare the meals. However, two interviewees disagreed. Mr. Shi said “I found more troubles with the restaurant during the pandemic, because restaurants are trying to cut costs by reducing the number of employees. Therefore, they took longer to prepare the meals.” Mr. Zhang also thought that restaurants tended to be slower because many employees went home during the Chinese Spring Festival. It seemed like restaurants had different responses to the pandemic, but there seemed to be a general trend that restaurants took less time to prepare their food.

All of the interviewees said that customers’ flexible schedules during the pandemic definitely helped their ratings. As hypothesized by the author, this flexibility in consumers’ schedules may have contributed to the increase in their patience which may explain this improvement in the customer ratings and the relationship between customers and workers.

On the topic of their social status and the respect they received from customers during the pandemic, seven out of eleven delivery workers exhibited a neutral attitude. They explained that the “zero contact policy” prevented them from having contact with the customers, so they didn’t sense significant changes. During the pandemic period, many apartment buildings did not physically allow delivery workers inside to control the spreading of the virus, so workers would leave the orders by the reception table. For many interviewees, they thought this policy made their life easier. But this limited human interaction is the cause of the neutral attitude. However, four interviewees expressed a positive attitude. Mr. Chen, a Meituan full-time delivery man, compared his experience before and during the pandemic:

When I delivered during the pandemic, customers were easier to satisfy and less picky. Before the pandemic, some of them would complain about really small things. Last year, when I received the meal from the restaurant, it was already very close to the time limit. I called and communicated with the customer, but he/she still gave me a bad rating (for being late) and it cost me 50 yuan. I appealed the decision, but Meituan still fined me. But during the pandemic, consumers were more flexible and forgiving when I was late for a few minutes, and they even said: “thank you”.

When asked about the kindest things he experienced from the customer, Mr.Wang told me that after the pandemic, he found that more customers would give out water, though this still happens very rarely. He said, “I am very thankful that they understood our hardships.” Besides being more patient, the customers also seemed to empathize with food delivery workers more. As people understood the difficulties of delivering during the pandemic through the media, they were more likely to empathize with those workers and treat them with more respect and kindness, which also explained why many workers felt an improvement in their social status.

5.Discussion

In terms of change in compensation, interviewees and the surveyed workers both reported a rather drastic income loss during the pandemic. The reasons for this decrease in compensation largely confirm the author's hypothesis. Firstly, the demand for food delivery dramatically decreased as there were no white-collar workers ordering regularly from their offices. Secondly, food delivery workers became an attractive occupation for people who got unemployed during the pandemic. Therefore, more newly recruited delivery workers heightened the competition between the workers, resulting in lower average income.

Compared to the drastic decline in income, the effect of COVID-19 on consumer ratings is less significant. As figure 2 shows that the majority of the survey respondents (56.83%) reported a positive change in ratings with varying degrees, while a significant portion of respondents (34.8%) responded neutrally. Some interviewees who shared the neutral opinion stated that they didn't have many bad ratings before, thus the pandemic may not have had a significant impact on their ratings.

Moreover, perhaps this distribution may also be explained by workers’ different experiences with restaurant preparation times in their respective areas. As explained by the interviews, restaurants played an integral role in this process and could either help or hinder the workers’ ability to deliver within the time constraint. Supporting this statement, figure 3 shares a similar pattern with figure 2, with 47.57% of respondents expressing that restaurants are faster during the pandemic and 33.04% expressing neutral responses. These similarities behind the two graphs suggest that the general trend of shorter meal preparation time may be correlated with workers' better ratings during the pandemic. During the interviews, although workers’ experiences with restaurants were different, they all agreed that consumers’ flexibility during the pandemic is helpful in obtaining a better rating. In conclusion, with increased flexibility of customers' schedules and a general decrease in restaurant preparation time, the majority of surveyed workers experienced a noticeable improvement in their ratings.

In terms of social status and customer respect, the positive impact from the media may not have been as significant as hypothesized by the author. In both Figures 4 and 5, the option of choosing “the same'' was very popular. In figure 4, 45.10% of the respondents believed that their social status remained the same, and 43.8% of respondents sensed a positive impact on their social status during the pandemic. In figure 5, 35.40% of the respondents sensed no significant shift in customer attitude and 54.9% of respondents sensed a positive change during their interaction with their customers during the pandemic. This neutral opinion is also shared by some interviewees who explained that perhaps the zero-contact policy limits their interaction with the customers, thus they are unable to sense a significant difference in customer respect or their social status. However, there were also workers who experienced a positive change in both areas, attributing it to customers’ flexibility and positive media attention.

Out of the 11 interviewees, none expressed that they experienced a decrease in social status or deterioration of their relationships with the customers, which wasn’t surprising considering the negative responses from Figures 5 and 6 are relatively rare. These results may support Happer and Philo to some extent, suggesting maybe the positive media portrayal plays a moderate role in shaping public perception of food delivery workers [14]. In conclusion, during the pandemic, many Chinese delivery workers experienced a modest improvement in both their social status and relationships with customers which might be a result of the increased flexibility of customers' schedules and positive media coverage, while many others expressed more neutral feelings as government policy prevented them from having more interaction with their customers.

6.Conclusion

During the pandemic, although many delivery workers experienced improvements in terms of their social status and relationship with their customers, the reasons behind these improvements were mainly temporary and unique features of the pandemic. Those reasons included positive media portrayal as the “heroes of the pandemic '', increased customers’ flexibility, and decreased restaurant meal preparation time. However, all of these factors were special events caused by the pandemic and none of them caused systemic changes. When the pandemic is eventually over, the media coverage of Chinese delivery workers will most likely decrease dramatically; customers will most likely return to their frantic schedules and require their meals to be delivered on time; restaurants will most likely prioritize eat-ins and prolong the food preparation time. In other words, the unequal structural relationship between customers and workers still exists in the Chinese food delivery platforms, but the customers just didn’t choose to take advantage of that as much.

The second important conclusion from this research is even though workers experienced higher social status during the pandemic, these improvements had yet to transfer to any tangible impact other than improved customer rating. This may suggest that, even amidst an unprecedented pandemic, the media can maybe change how the public treats a specific population personally, but are unable to catalyze systemic improvements for their working conditions. Fortunately, if the improvements in their social status and relationship with the customers were only situational to the pandemic, the decline in workers’ wages will also be temporary. If the declining wages were caused by decreased demand in food deliveries and increased supply of workers, the delivery workers’ wages will most likely return to normal when more people order food deliveries and newly joined delivery workers go back to their previous jobs that were closed down because of the pandemic. In order to cause long-term systemic improvements for the Chinese delivery workers, better governmental policies and more compassionate technology design are needed. Government should develop a better definition of employees to provide full-time Chinese delivery workers with labour rights and benefits. And the platforms can better design their algorithm to improve workers’ safety, such as giving workers more time to deliver when there is a traffic jam. From this study, we can conclude that media coverage is not enough to fundamentally improve the living conditions of the gig workers, and both public and private efforts are needed to create a better working environment for the workers.

However, this study has two main limitations: the limited scope and voluntary response bias. First, the scope of this study is limited. The researcher only surveyed 227 workers and interviewed 11 workers. And workers from certain geographic locations were not represented in this study. So, the results from this research may not accurately represent more than 6 million delivery workers in China. Second, the workers responded to the surveys voluntarily, which may introduce a voluntary response bias to the results. As participants were self-selected, they may only respond because they have a pretty strong opinion on the subject. Therefore, this sampling method might result in producing a more significant result than the reality. Although the researcher added monetary incentives to complete the survey to attract more workers with more neutral perspectives to answer the survey questions, the inherent bias in the method still existed.

While this study focused on the experience of Chinese delivery primarily during the pandemic, future research is needed for examining any lasting impact of the pandemic on Chinese food delivery workers. Once the pandemic is over, it would be interesting to see if the improvement of social status remained after the pandemic and if that resulted in any material improvements of the Chinese food delivery workers. The question for future research remains: will this increase in social status and respect for Chinese delivery workers be a catalyst for long-term change in the working conditions of Chinese delivery workers?

References

[1]. Ma, Jin Qian. "400,000 food delivery orders per day, and 20,000 active food delivery workers in Beijing during the pandemic". Beijing News, Baidu.com, baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1657686252308508204&wfr=spider&for=pc. 5 Feb. 2020.

[2]. UK, Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy. The Characteristics of Those in the Gig Economy. By Katriina Lepanjuuri et al., Feb.wo kan

[3]. Campbell, Charlie. "Behind the Covers of TIME's Special Coronavirus Issue." Time, Mar. 2020, time.com/5805947/time-coronavirus-covers/.

[4]. Liu, Weijun, and Wojciech Florkowski. "Online Meal delivery services: Perception of service quality and delivery speed among Chinese consumers." Southern Agricultural Economics Association (SAEA) 2018 Annual Meeting, Feb. 2018.

[5]. "Report on the development of the Chinese Food Delivery Industry 2019-2020 ". Meituan Research Institute, 28 June 2020. Meituan.com, about.meituan.com/news/institute.

[6]. Sun, Ping. "Your Order, Their Labor: An Exploration of Algorithms and Laboring on Food Delivery Platforms in China." Chinese Journal of Communication, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 308-23. World Religions: Belief, Culture, and Controversy, 26 Mar. 2019.

[7]. Levy, Karen, et al. "Discriminating Tastes: Customer Ratings as Vehicles for Bias." Intelligence and Autonomy, datasociety.net/pubs/ia/Discriminating_Tastes_Customer_Ratings_as_Vehicles_for_Bias.pdf, Oct. 2016.

[8]. Hochschild, Arlie Russell. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Updated, with a new preface. ed., Berkeley, U of California P, (2012).

[9]. "First half of 2019 Shanghai Delivery Traffic Accidents Report". CNR, , www.cnr.cn/shanghai/shzx/ms/20190707/t20190707_524682255.shtml, 6 July 2019

[10]. [Pan, Shan L., et al. "Information Resource Orchestration during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Study of Community Lockdowns in China." International Journal of Information Management, vol. 54, p. 102143. ScienceDirect (Oct. 2020)

[11]. Wang, Jing Xue. "Food Delivery Workers from Wuhan Volunteered to Deliver to the Hospitals". Xinhuan News, Xinhua Net, www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2020-03/13/c_1125704679.htm ,13 Mar. 2020.

[12]. "One Food Delivery Workers is Diagnosed with COVID-19". DianShangBao, Baidu, baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1657622716668119442&wfr=spider&for=pc. (5 Feb. 2020)

[13]. "Food delivery workers Hui Wu". Tencent News (CCTV), Tencent Net, new.qq.com/omn/20200223/20200223A0I9DC00.html?pc. 23 Feb. 2020.

[14]. Happer, Catherine, and Greg Philo. "The Role of the Media in the Construction of Public Belief and Social Change." Journal of Social and Political Psychology. Psychopen.eu, jspp.psychopen.eu/article/view/96.

[15]. Hammond, John L. "The MST and the Media: Competing Images of the Brazilian Landless Farmworkers' Movement." Latin American Politics and Society, vol. 46, no. 4, , pp. 61-90. JSTOR (Winter 2004).

[16]. " In 2019, 3.987 million riders received income from Meituan, and new riders added 336,000 during the epidemic". Xinhuan News, Xinhua Net, http://www.xinhuanet.com/tech/2020-03/19/c_1125736688.htm 19 Mar. 2020.

[17]. "Report on the Chinese Food Delivery Industry (first three quarters of 2019) ". Meituan Research Institute, Meituan.com, about.meituan.com/news/institute, 28 June 2020..

[18]. Lecky, Prescott. Self-Consistency; A Theory of Personality. Island Press, 1945.

Cite this article

Chen,Z. (2023). The impact of COVID-19 on the standard of living of Chinese food delivery workers in the gig economy1. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,3,36-47.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Economic Management and Green Development (ICEMGD 2022), Part Ⅰ

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Ma, Jin Qian. "400,000 food delivery orders per day, and 20,000 active food delivery workers in Beijing during the pandemic". Beijing News, Baidu.com, baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1657686252308508204&wfr=spider&for=pc. 5 Feb. 2020.

[2]. UK, Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy. The Characteristics of Those in the Gig Economy. By Katriina Lepanjuuri et al., Feb.wo kan

[3]. Campbell, Charlie. "Behind the Covers of TIME's Special Coronavirus Issue." Time, Mar. 2020, time.com/5805947/time-coronavirus-covers/.

[4]. Liu, Weijun, and Wojciech Florkowski. "Online Meal delivery services: Perception of service quality and delivery speed among Chinese consumers." Southern Agricultural Economics Association (SAEA) 2018 Annual Meeting, Feb. 2018.

[5]. "Report on the development of the Chinese Food Delivery Industry 2019-2020 ". Meituan Research Institute, 28 June 2020. Meituan.com, about.meituan.com/news/institute.

[6]. Sun, Ping. "Your Order, Their Labor: An Exploration of Algorithms and Laboring on Food Delivery Platforms in China." Chinese Journal of Communication, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 308-23. World Religions: Belief, Culture, and Controversy, 26 Mar. 2019.

[7]. Levy, Karen, et al. "Discriminating Tastes: Customer Ratings as Vehicles for Bias." Intelligence and Autonomy, datasociety.net/pubs/ia/Discriminating_Tastes_Customer_Ratings_as_Vehicles_for_Bias.pdf, Oct. 2016.

[8]. Hochschild, Arlie Russell. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Updated, with a new preface. ed., Berkeley, U of California P, (2012).

[9]. "First half of 2019 Shanghai Delivery Traffic Accidents Report". CNR, , www.cnr.cn/shanghai/shzx/ms/20190707/t20190707_524682255.shtml, 6 July 2019

[10]. [Pan, Shan L., et al. "Information Resource Orchestration during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Study of Community Lockdowns in China." International Journal of Information Management, vol. 54, p. 102143. ScienceDirect (Oct. 2020)

[11]. Wang, Jing Xue. "Food Delivery Workers from Wuhan Volunteered to Deliver to the Hospitals". Xinhuan News, Xinhua Net, www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2020-03/13/c_1125704679.htm ,13 Mar. 2020.

[12]. "One Food Delivery Workers is Diagnosed with COVID-19". DianShangBao, Baidu, baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1657622716668119442&wfr=spider&for=pc. (5 Feb. 2020)

[13]. "Food delivery workers Hui Wu". Tencent News (CCTV), Tencent Net, new.qq.com/omn/20200223/20200223A0I9DC00.html?pc. 23 Feb. 2020.

[14]. Happer, Catherine, and Greg Philo. "The Role of the Media in the Construction of Public Belief and Social Change." Journal of Social and Political Psychology. Psychopen.eu, jspp.psychopen.eu/article/view/96.

[15]. Hammond, John L. "The MST and the Media: Competing Images of the Brazilian Landless Farmworkers' Movement." Latin American Politics and Society, vol. 46, no. 4, , pp. 61-90. JSTOR (Winter 2004).

[16]. " In 2019, 3.987 million riders received income from Meituan, and new riders added 336,000 during the epidemic". Xinhuan News, Xinhua Net, http://www.xinhuanet.com/tech/2020-03/19/c_1125736688.htm 19 Mar. 2020.

[17]. "Report on the Chinese Food Delivery Industry (first three quarters of 2019) ". Meituan Research Institute, Meituan.com, about.meituan.com/news/institute, 28 June 2020..

[18]. Lecky, Prescott. Self-Consistency; A Theory of Personality. Island Press, 1945.