1. Introduction

Gender binary outfit expectations are a legacy of traditional patriarchal societal values; they refer to societal expectations regarding the apparel and fashion styles that are deemed acceptable for men and women based on their gender [1]. These expectations reinforce the notion of a gender binary and that each gender should adhere to a distinct set of apparel and fashion standards. In many societies, for instance, men are expected to wear trousers or suits while women are expected to wear dresses or skirts. Not only the styling of outfits is denoted with a gendered lens, but to a certain extent, scholars find colours are also associated with gender expression. People develop their preliminary cognition of “gender-typed” clothing at an age between “3-to-6-year-old”. For girls, “⅔” of the "gender-rigidity cognition in appearance develops in the age of 3-4, and almost half of the boys gain such cognition in the age of '5-6' [1]. For instance, being "pink” can be referred to as "girly," while colours of high saturation like "blue" and "red" with the symbolism of boldness and masculinity are deemed appropriate to advocate by parents. The existence of gendered-outfit cognition affects the developmental formulation of children’s gender and personal identity. This was not directly related to “parents' preferences” [1]. However, it is shaped by the historical dichotomy of gender in society. Many aspects of society reflect these expectations, including dress codes in schools and workplaces, attractiveness standards, and cultural norms. Both members of the gender binary community tend to reinforce this gender binary. As a manifestation, derogatory epithets like 'fag' are used against adolescent boys who show feminine traits [2]. On the contrary, slut shaming is pervasive in society as a label to refer to females who are perceived as sexually promiscuous [2].

The double standard in the online community can be perceived as a projection of actual society [3]. Precarious manhood theory reflects gender rules like “prescriptions” and “proscriptions” in double standards. Some behaviours and decisions are endorsed more by men than women, while others are more desirable and preferred by men than women. This tradition of interpreting women as the ‘second sex’ can be manifested in the usage of languages [4]. For example, Chinese and English as the top two used languages in the world denote that 'people=male’ [5]. The same logic applies to suffixes when referring to an occupation differently for females to males [4]. For instance, “Nulaoshi (female teacher)” refers to a female teacher, while “Laoshi (teacher)“ refers to the teacher. "Waiter" refers to a service worker, while "waitress" refers to female service workers. These apparent segregations in the language function as a lens projecting gender differences in the workplace and even in day-to-day life [4].

Some studies show that people perceive dominance more favourably in men than in women, while they view being “communion” as more desirable for women than for men [6]. Prescriptions vary from country to country, whereas prohibition appears to be universal. For instance, in contrast to the weakness of males, dominance is less desired for women. The prevalence of double standards in prescriptions is greater in countries with lower gender equality and human development, whereas double standards in proscription are unrelated to country-level factors [6]. These patterns are moderated in nuanced ways by participant gender and are robust to individual-level gender beliefs. Statistically, women are confronting more disadvantageous criticism when it comes to not meeting the expectations and unspoken rules of double standards. Women are more likely to experience gender-based violence, such as sexual harassment, assault, and domestic violence than men. According to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center, one in four women has experienced sexual violence in the United States [7].

The discussion between men and women is permeated by gender-related topics as a projection, but only as a wilder reflection of the traditional gendered vision since netizens are more open about their comments with fewer regulations and supervision online. Misogyny is deeply rooted in the paternal and patriarchal conflict society holds against women. There are three main categories of appearance-related double standards that women encounter: online sexual harassment, online appearance criticism, and slut shaming [8]. The first category that reflects online double standards is online harassment, where women are more likely than men to be the target. 41% of females in the US have experienced online harassment, compared to 37% of male victims. Secondly, criticisms are highly directed at female online users, who are under greater scrutiny from other netizens. These criticisms can be body shaming, "lookism,” or "ageism.” Supporters can make judgments on the condition of hair and skin. Not to mention the styling of clothes may also be a reason why women are attacked online [9]. Last but not least is the vicious cycle of "slut shaming." Women who post photos of themselves wearing revealing clothing may be called derogatory terms such as "slut" or "whore” [2]. In contrast, men who post shirtless pictures are frequently praised and encouraged. Slut shaming will be discussed in the next section pertaining to CSV. Apart from that, double standard expectations pertaining to “workplace” and “parenting” scenarios tend to favour men over women [10].

Cyber sexual violence is a form of sexual violence perpetrated through the means of digital platforms like social media, texting, or messaging apps. It is a deliberate act to control, disgrace, and humiliate people; this problem is predominantly directed at women and marginalised communities. Especially EYW (emerging young women) going through emotional volatility [11]. Cyber-SV is perpetrated by male and female perpetrators who may or may not be known to EYW but record, distribute, and view graphic images and videos with or without their consent. Cybersexual violence can have serious negative impacts on a person's mental health, self-esteem, and sense of safety and security. If it lingers for the long term, it can have long-lasting and severe consequences for victims' well-being and engagement in the offline community, including emotional trauma, anxiety, melancholy, and even suicide [11]. The majority of cyber sexual violence against EWY takes place in academic institutions. The institutions lack the requisite knowledge and expertise for intervention, prevention, and support [11]. To promote gender equality and prevent cyber-sexual violence against EYW, there is a need for progressive reforms to criminal and privacy laws [11].

Misogyny is ingrained in gender stereotypes and embedded societal norms that manifest hate towards women through behaviours like discrimination, objectification, sexualisation, harassment, and violence toward the female community. It can be considered a ‘hate crime’ since women as a community are targeted and victimised solely because of their “identity” [12]. Such a societal norm is a reaffirmation of the unequal hierarchy between social gender order politically and socially and a hegemonic mechanism that places women in an oppressed position whereas men are empowered [12]. Such oppression exists in numerous contexts, such as the workplace, politics, the media, and social interactions [12]. Participation in leadership roles in political realms like the national parliament and local government can demonstrate such power imbalances in the workplace. Statistically, there are only 34 women who serve as heads of state and/or government in the world [13]. Local government only consists of 34% women out of 136 counties, and only 26.5% of parliamentarians are women [13]. However, women's role is not limited to being victims of misogyny; they can even be the “reinforcer” of this cyclical hatred against women. "Internalised oppression” is when women hold discriminatory perspectives against other women as a sign of “reinforcing male dominance” and “female subordination” [2]. This pervasive threat is a manifestation of ensuring conformity with hegemonic masculinity [2].

This essay examines the gender-based double standards evident in online cyber-shaming of women's clothing choices. The paper will investigate how netizens react differently to men's and women's clothing by analysing case studies and examples from a variety of contexts. The essay contends that cybershaming of women's outfit choices is rooted in deeply ingrained gender stereotypes and expectations that limit women's freedom of expression and self-determination opportunities. This essay seeks to contribute to the ongoing conversation about gender equality and empowerment and to advocate for greater awareness and action to counteract cyber shaming and gender-based double standards in dress codes. With the recognition of gender minorities (SGM), variety in personal identity recognition in current society, and LGBTQIA+ community, and their freedom of personal expression in clothing [14]. The scope of this paper only stays in the realm of the gender binary. Online harassment can traumatise the offline lives of victims and be a stimulus for pushing them to commit suicide. Cyber-shaming extends beyond the immediate harm inflicted on women, as it intensifies gender-based double standards and reinforces gender inequality. With the above-mentioned consequences that come along with gender-based double standards. This investigation is interested in the following research questions:

1.How do the online community reflect gender-based double standards?

2.What are the Impacts of cyber shaming on EYW?

3.To what extent do women contribute to misogyny?

Cyber shaming is a relatively new phenomenon that has gained momentum in recent years, predominantly as a result of the rise of social media platforms such as Instagram, Twitter, and TikTok [11]. Cyber shaming is frequently directed at women who post photographs of themselves donning clothing that challenges traditional gender roles or societal norms or deviates from societal expectations. Data shows that 18.7% of young people had been called a “slut” on social networks, while 21% of girls aged under 14 experienced slut shaming, which is particularly concerning since such pejorative language can impact mental health and identity formation for EYW [8]. One out of four participants stated that they had been the target of sexual rumours in the six months before the study, and it was found that 80% of the people who took part had observed sexist comments like "slut shaming" used online [8]. Women, in many aspects, are disadvantaged by gender-based double standards. Thus, this essay hypothesises that when it comes to outfits, there is more criticism directed at women. Therefore, it is hypothesised that: H1. Outfit-based content to manifest judgments and criticism in the comment to be harsher for women.

Criticisms and judgments essentially have more impact on youth who are aged between 15-25 [15]. One of the reasons is that youth are more volatile in values since they are at the stage of exploring their self-identity, in which gender is part of the identity manifestation in public. Secondly, they are exposed to and influenced by their close peers [16]. Most importantly, they are at their stage of development and are forming an understanding of the existing paternal societal values [1]. Above mentioned reasons cause fluctuating mental conditions, and a higher chance of struggling with mental illness in youth than in other age ranges. Statistically, more than 75% of mental health conditions occur before the age of 25 [17]. With 10% of disorders affecting their normal functioning, and another 10% being diagnosed with less severe forms of the same disorders [18]. Access to information and the connectivity of digital media have exposed youth to negative sides that are usually protected from them by their parents. Such highly diverse content can be explicit and harmful to the development of youths with fewer regulations compared to the real world from all ages and all social statuses [16]. Therefore, it is hypothesised that: H2. The impact of cyberbullying on emerging young women is greater than at other ages.

The legacy of “Poxiguanxi(The relationship between mother-in-law and daughter-in-law)” is a long-discussed family and societal issue that extends in China from the past to these days. Some argue that this conflict in the relationship between mother-in-law and daughter-in-law is not solely repression from the mother of one family to the married woman; the common existence across time and space provides consistency to make this conflict a phenomenon that posits the nature of internal oppression from one female to another female [19]. Some suggested that the mother-in-law who experienced unhappy repression as a power minority when she was a daughter-in-law to her family, has not turned into a mild mother when she is in a position of power. However, she acts as a "reinforcer" of “female subordination," giving burden and responsibility as a legacy that is carried from her daughter-in-law stage [2]. In light of this, this essay hypothesises H3. Women aggravate the effect of the misogyny complex.

2. Methodology

To investigate the above-mentioned research question and verify the hypothesis, the essay will be sectioned into three major parts investigation, where study 1 will be branched into two parts. Study 1a focuses on exploring the role of gender-based double standards in people’s interaction in the online community and its contribution to gender problems offline. Study 1b delves into two case categories of appearance shaming toward females — outfit shaming and body shaming, each will be analysed with a case study. Study 2 is dedicated to the repercussions of cyberbullying and online criticisms on EYW’s offline lives and its lethal impacts. Study 3 emphasises the influence of women in solidifying misogyny in society.

In Study 1a and Study 3, a questionnaire consisting of 14 questions and an attached demographic questionnaire is created and released. We tested these hypotheses by reading and analysing answers received from questionnaires to analyse the appearance criticism women received, its implications in gender-based double standards, and the extent to which they supported the statement “women reinforce misogyny".

In Study 1b, data collected in the questionnaire from the sample population will be analysed to reveal the inclination of people in online communities to speculate about other people’s offline lives based on appearance. The two case categories appearance shaming on females, outfit shaming and body shaming, will be analysed with a case study of each category. The first part consists of a graphical representation generated from questionnaire data collection showing participants’ tendency to assume other people’s backgrounds like career background, and educational background, based on online outfits. In the second part, two incidents illustrate outfit-shaming and body-shaming, which are universal and typical. They demonstrate how online criticism of women's looks can negatively impact their lives offline. A case study on the suicide of Zheng Linghua, widely known as the suicide of the ‘pink-haired girl’ in China, will be covered [20]. This case addresses the issue of netizens' assumptions and criticisms of others based on outfits and hair. In the body shaming case, a Japanese girl named Hana Kimura from the wrestling industry committed suicide due to body shaming and online criticism [21].

Study 2 investigates the relationship between cyberbullying and the mental well-being of EYW. Emerging young women encountering distinct problems that necessitate focused consideration have come to the forefront. EYW contends with the burdensome weight of cultural expectations, the relentless pressures surrounding body appearance, and the pervasive issue of gender-based violence. A two-way ANOVA analysis based on the statistics from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare to verify the urgency of the consequences of cyberbullying on EYW through the method of hypothesis testing and comparing the results with those of two other communities—emerging young men and grown women [22]. It is hypothesised that EYW has higher rates of suicide than the other two compared groups. Two hypothesis tests:

1. Test 1(gender)

H0: Gender has no impact on suicidal rates

H1: Women's suicidal impacts from cyberbullying are smaller or greater than those of males of the same age

2. Test 2(age)

H0: Age has no impact on suicidal rates

H1: EYW has a higher or lower suicide rate than women of other age groups

2.1. Results Analysis

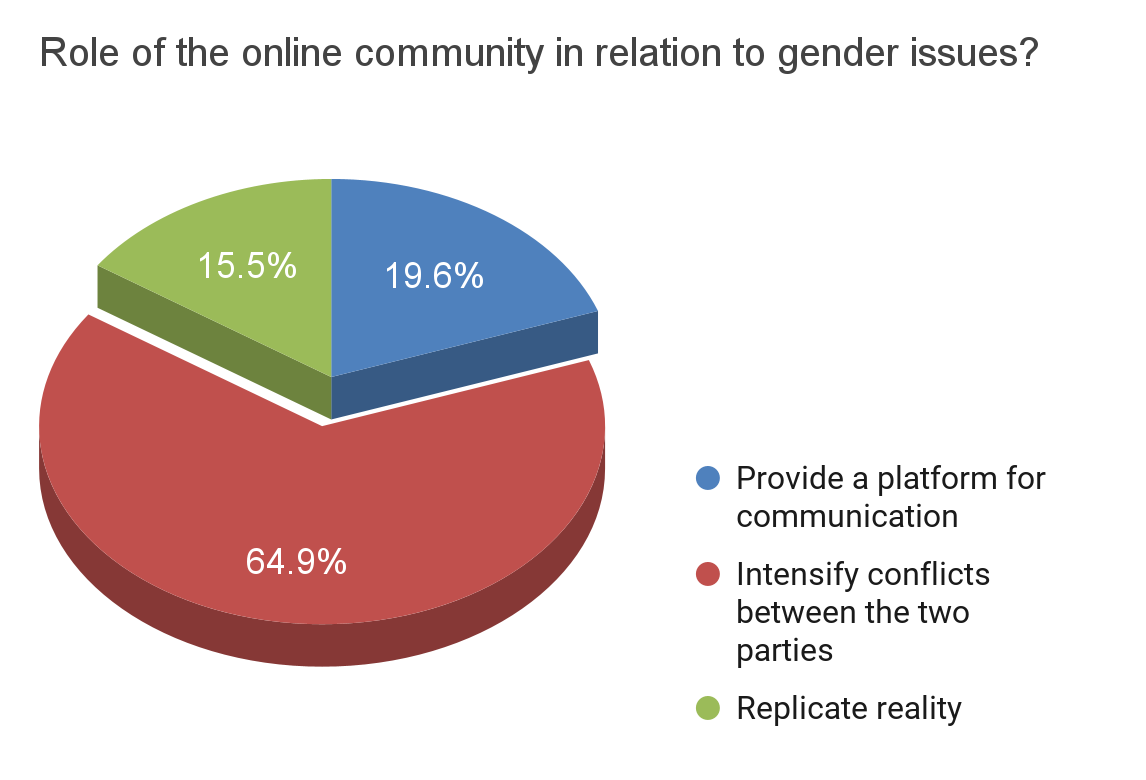

Hypothesis 1 is proven true and hence this indicates that the response to research question 1 is that Outfit-based content manifests judgments and criticism in the comment to be harsher for women. Below is a visual representation demonstrating how the sample population sees the role that online communities serve in gender-related issues. They were given three options in the multiple choice problems, where the function ‘intensify conflicts between the two parties’ ranked top in their votes by yielding 64.9%, which is far more than the other two options. In light of this, this investigation is aware of how the online community functions as a magnifier that would escalate the already existing issue between the two genders online.

Figure 1: Percentage of participants’ views on the online community in gender issues

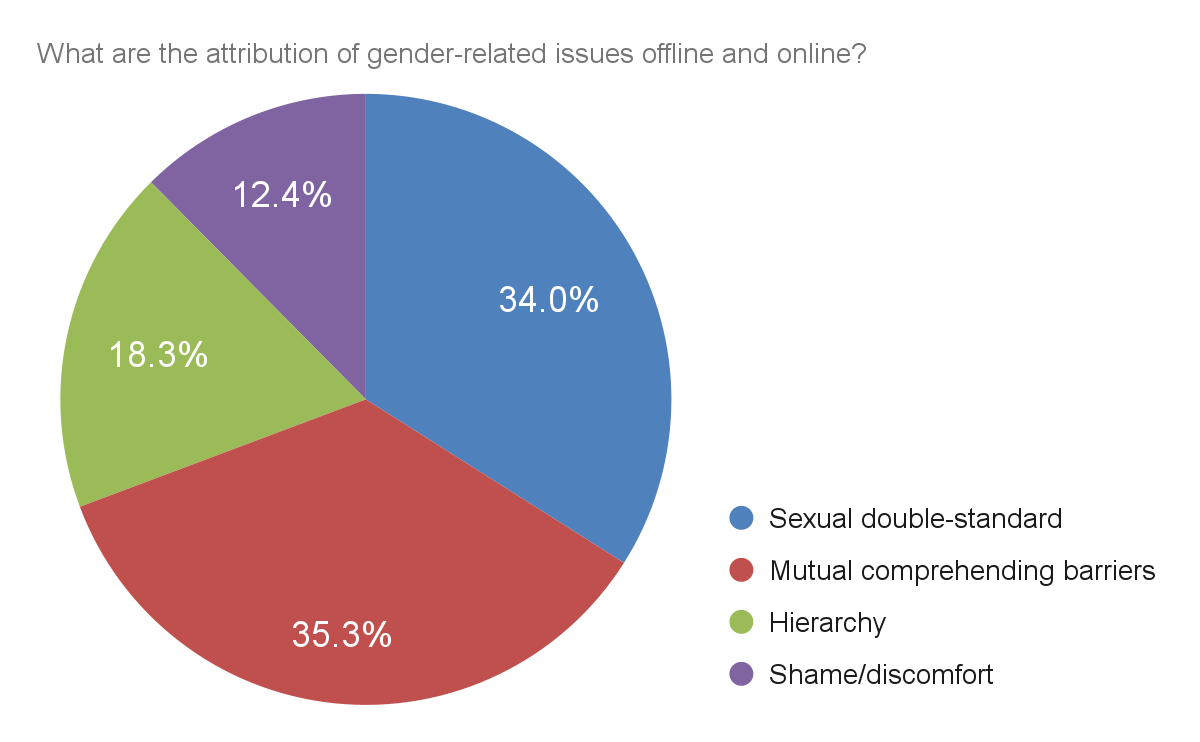

Apart from the magnifying nature of online community to issues pertaining gender disputes, this questionnaire indicated that ‘sexual double-standard’ here were one of the two major attributions to gender related issues both in online community and in offline society. Both these attributions takes up over a third of all received response out of four options. Apart from these provided options, some participants supplemented additional attributions like: “patriarchy”, “prejudice” passed from the past in “gender concepts”, and “society” with a “male-dominated” nature.

Figure 2: Percentage of participants’ views on the attribution of gender-related issues

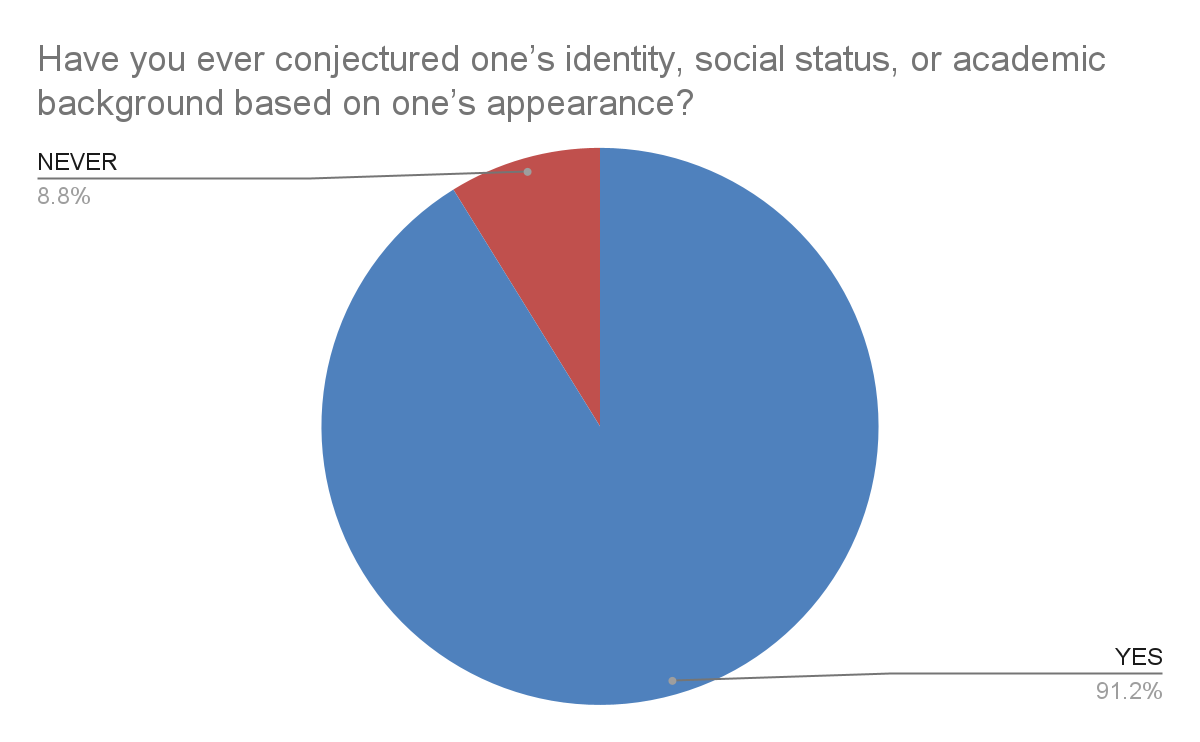

During the exploration of study 1b, outfit-based content manifests judgments and criticism in the comment to be harsher for women. The graphical representation below generated from questionnaire data collection shows participants’ tendency to assume other people’s backgrounds like career background, and educational background, based on online outfits.

Figure 3: Visualised statistic for the percentage of participants who conjectured others’ background based on one’s appearance

The widely known case study on the suicide of the ‘pink-haired girl’, Zheng Linghua illustrate how online outfit-shaming and appearance-shaming do to a young lady’s emotional status and psychological well-being [20]. Upon sharing a photograph on her "Xiaohongshu"(Chinese social media) profile, Zheng was taken aback to see herself subjected to cyberbullying due to her hair being coloured pink. The snapshot depicted her reading an admissions letter with her bedridden grandfather. Her haircut was derogatorily associated with prostitution, with others labelling her as a "club girl" or an "evil spirit." Certain individuals have taken possession of her photographs and utilised them as promotional materials to market educational programmes, while others have gone so far as to exploit the photographs to propagate malicious rumours concerning elderly men marrying younger women. Many WWE wrestlers have encountered instances of bullying, with female wrestlers frequently being subjected to body shaming and criticism over their wrestling skills. It is imperative to recognise that male wrestlers are also subjected to bullying. As social media users, it is incumbent upon us to acknowledge the person behind the online identity and to comprehend that comments can truly inflict harm on persons. Hana Kimura sadly died from cyberbullying following her involvement in the Japanese reality show Terrace House, thereby emphasising the profound detrimental effects it may have on an individual's overall welfare. The wrestler ultimately succumbed to her struggles and made the decision to end her life [21].

For research question 2, the investigation is based on data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, which is the state agency for health and welfare-related information and statistics. This investigation trimmed the originally recorded year from 1907-2022 to the recent decade of record to 2012-2022 with consideration to the time relevance for the research. This investigation also removed the measuring units ‘persons’ and ‘number’ to support analytical consistency and conciseness. The result of the hypothesis testing investigation turned out to be the opposite of the original hypothesis, which is that the impact of cyberbullying on emerging young women is smaller than at other ages and for boys of the same age. The original research hypotheses are listed below:

Test 1(gender)

H0: Gender has no impact on suicidal rates

H1: Women's suicidal impacts from cyberbullying are smaller or greater than those of males of the same age

Test 2(age)

H0: Age has no impact on suicidal rates

H1: EYW has a higher or lower suicide rate than women of other age groups

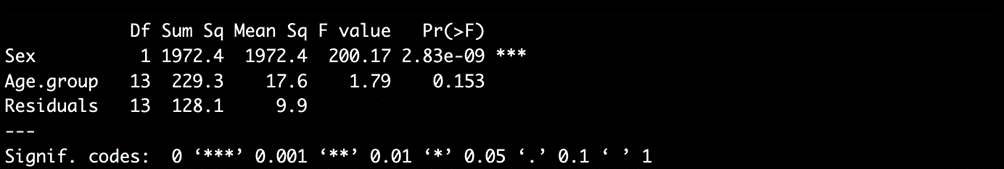

Figure 4: Two-way ANOVA test on Sex, Age group, and Suicide rate

According to the two-way ANOVA test above, it is shown that the ‘p-value’ for sex variable turned out to be “0.00000000283”. Since the p-value is smaller than 0.05, it is considered to be statistically significant, meaning the null hypothesis should be rejected. In this case, the H0 is ‘Gender has no impact on suicidal rates’ and the alternative is ‘Women's suicidal impacts from cyberbullying are smaller or greater than those of males of the same age’. This means that the correlation between sex and suicide rates is high. In comparison, the age variable has a smaller connection to the suicide rates since it has a ‘0.153’ p-value, which is greater than 0.05. Hence, is considered to be statistically not significant, meaning the null hypothesis should not be rejected. In this case, the H0, ‘Age has no impact on suicidal rates,’ is accepted as true.

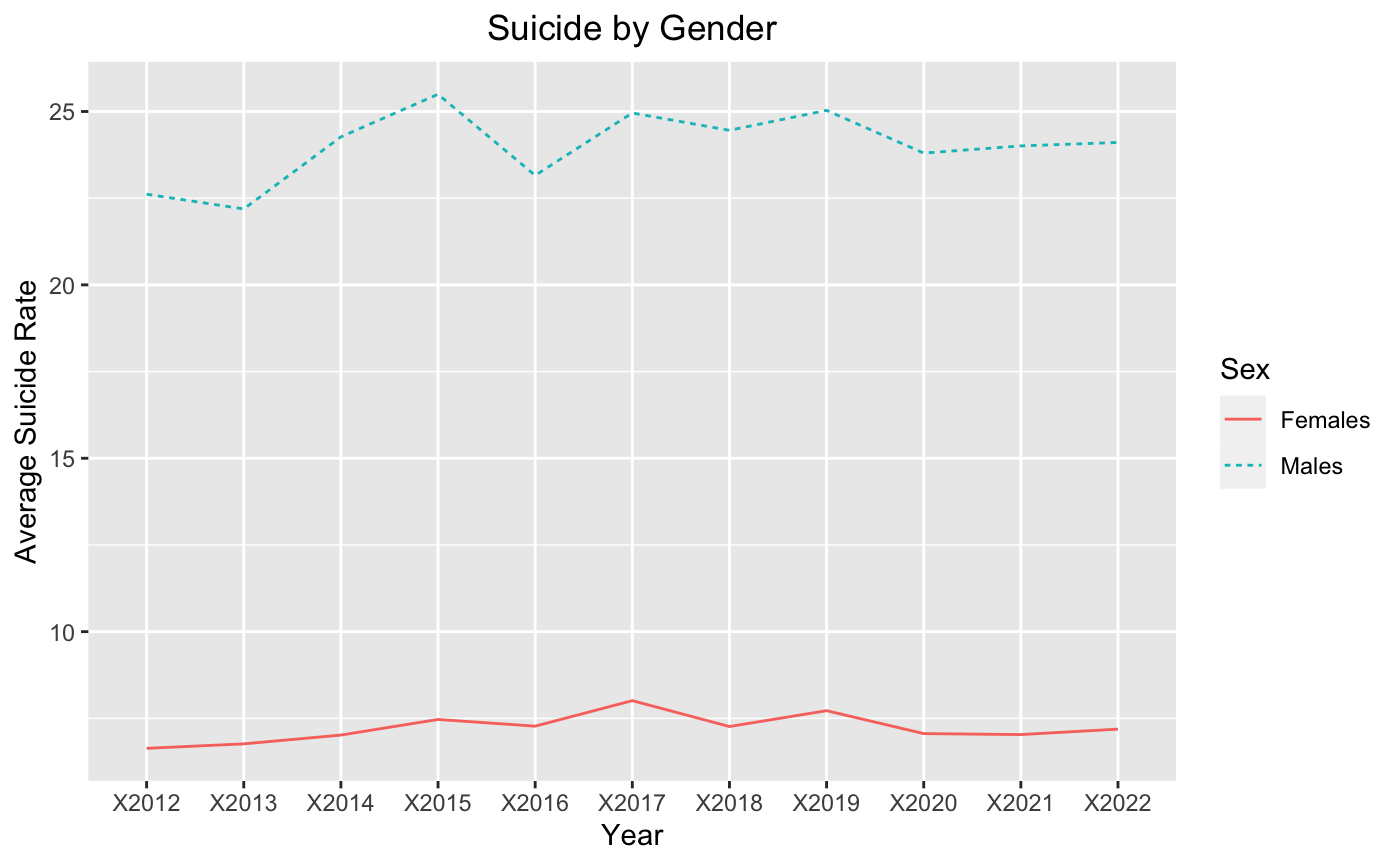

Figure 5: Line graph for Suicide rate by Gender

After rejecting H0 and accepting the alternative for Test 1, it is known that the sex variable has an impact on the suicide rate. The alternative stated that women have either higher or lower suicide rates; figure 5 above demonstrates an overall higher male suicide rate than females. The mean male suicide rate is 24.00779, which is more than triple the female suicide rate of 7.221753.

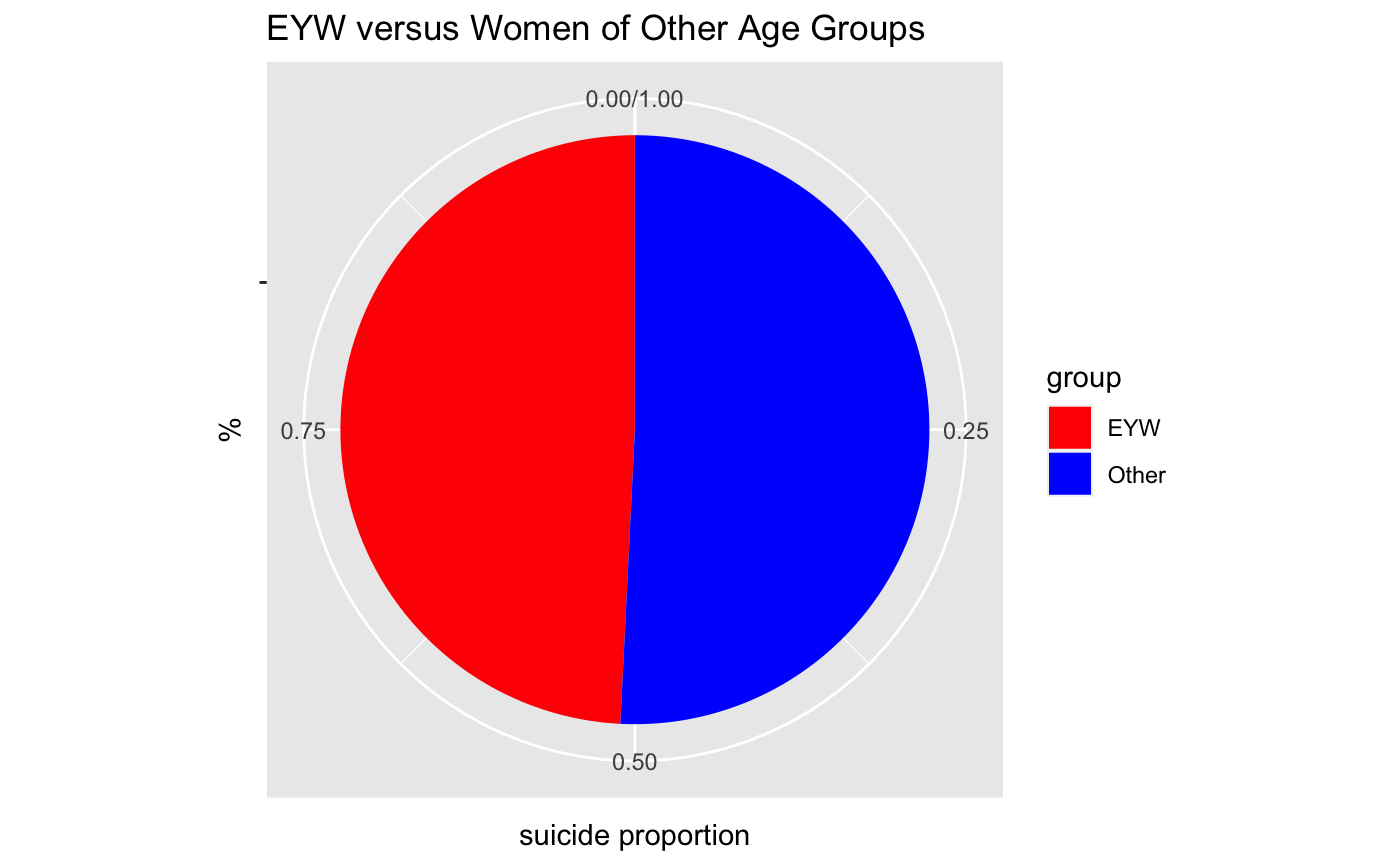

Figure 6: Pie chart for Suicide rate comparing EYW and women of other age groups

This research then limits the analysis to females only, by first bisecting the data category to EYW—which is 15-24—and women of other age groups [23]. After accepting H0 for Test 2, it is known that the age variable has relatively little impact on the suicide rate. Figure 6 above displays an identical share of suicide rates among EYW and women of other age groups. The same pattern is again tested on the mean; the mean for the EYW suicide rate is 7.013636, which is a little less than 7.237762 for that of women of other age groups.

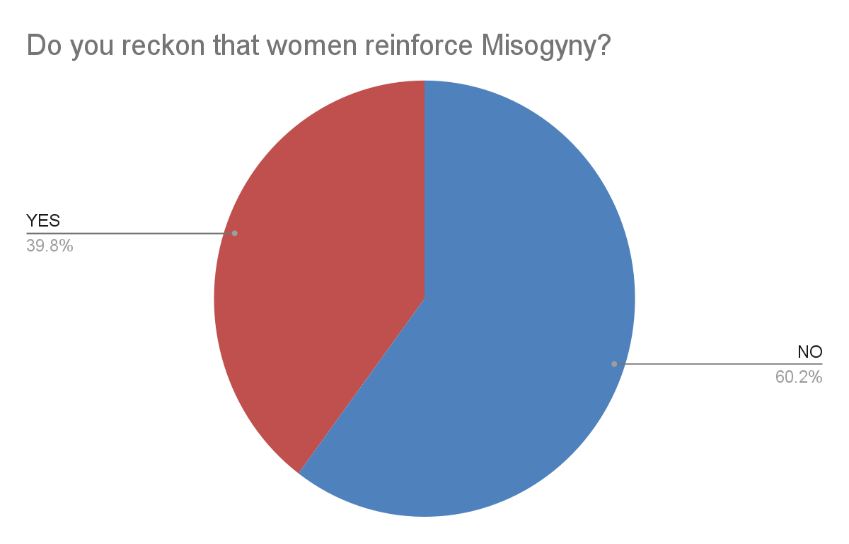

Figure 7: Visualised statistic for percentage of participant who reckons women reinforce misogyny

As we can see from the visualisation above analysed from the questionnaire responses, it is demonstrated that approximately over ⅖ of the sampled population responded with a positive note acknowledging that “women reinforce misogyny”. Even though the misogyny complex is a disputed social phenomenon with various roots, women are an internal influence that reinforces misogyny. There are several overlapping contributing factors provided by the respondents as to why women deepen misogyny. A number of participants pointed out that the mothers-in-law who used to be the daughters-in-law when they were younger took advantage of their identity and suppressed their daughters-in-law, instead of looking out for female fellows. Other participants reckon the "privileged wives" may contribute to the intensification of misogyny to a certain degree. It also occurs that some participants assert themselves as radical women without possessing a profound comprehension of women's rights, or exploit women's rights as a distinctive identity to showcase their behaviour, which is repugnant.

3. Conclusion

The discourse pertaining to gender-based disparities and inequities in online culture provides an entry point to a more extensive dialogue concerning societal conventions, virtual environments, and the ramifications of these dynamics on personal encounters. The examination of the objectification of feminine sexuality, limitations on self-expression and appearance, and the widespread occurrence of cybershaming clearly demonstrates the continued existence of gender biases in the online domain. These biases not only reflect but also frequently intensify the biases observed offline.

An essential aspect of this discussion is the requirement for a fundamental change in how we navigate and control online places. The dehumanisation of female sexuality, as demonstrated by the uninvited dissemination of graphic material and insulting comments, highlights the need for a more stringent enforcement of online manners. Online platforms should implement proactive measures to mitigate such behaviour, cultivating an environment that promotes respect and inclusivity.

An important constraint on this topic is the possible absence of diversity in the sample population being analysed. The manifestations of gender-based double standards and inequities can vary considerably within distinct cultural, socio-economic, and regional contexts. For instance, data used in Study 2 is selected from AIHW, which is an Australian national information institution. It is possible that statistics from AIHW are not globally representative. To have a more thorough comprehension, it is necessary to obtain a wider and more inclusive sample that encompasses the intricacies of this multifaceted matter.

The approach mostly examines gender inequalities in internet culture without thoroughly investigating intersectionality. It is also noted that the result failed to meet the hypothesis in study 2. it is possible that the women of other ages and men face cyberbullying as well as other burdensome consequences in their lives. Even though the hypotheses are rejected or proven not true. The severity of emerging young women’s mental health consequences is not nullified on the grounds of the abundance of suicide cases happening every year, not to mention the significance of their mental health in these pivotal developmental years to their future. Further investigation is warranted to explore the intricate interplay between race, sexual orientation, socio-economic position, and gender dynamics, and how these characteristics contribute to distinct manifestations of online inequalities.

The online culture is characterised by its dynamic and ever-changing nature. The conclusion presented here represents a momentary depiction and may not encompass evolving patterns or changes in cultural perspectives. Ongoing research and improvements are essential to keep up with the constantly evolving nature of internet interactions.

In conclusion, the pervasive presence of gender-based double standards and inequalities in online culture represents a significant societal challenge. The objectification of feminine sexuality, constraints on self-expression, and the prevalence of cybershaming contribute to a toxic environment that disproportionately affects women. This not only hinders their ability to participate fully in the digital sphere but also perpetuates harmful stereotypes and fosters an atmosphere of discrimination.

Addressing these issues requires a multifaceted approach. It involves promoting digital literacy to encourage responsible online behaviour, fostering inclusive and respectful online communities, and holding platforms accountable for creating safe spaces. Empowering women to reclaim control over their self-expression and appearance is crucial in dismantling harmful double standards. Only through collective efforts can we hope to create a digital landscape that respects and uplifts individuals, irrespective of gender, fostering an environment where everyone can thrive without fear of objectification or cybershaming.

As this research stated in the early pages, this investigation wishes to call for progressive reforms in criminal and privacy legislation that are necessary to advance gender equality and combat cybersexual violence against individuals of all genders. This research also appeals to relevant social facilities and professionals for the well-being of every EYW as online life and social media permeate and affect this community more than any other groups.

References

[1]. Halim, M. L., Ruble, D. N., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Zosuls, K. M., Lurye, L. E., & Greulich, F. K. (2014). Pink frilly dresses and the avoidance of all things “girly”: children’s appearance rigidity and cognitive theories of gender development. Developmental Psychology, 50(4), 1091–1101. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034906

[2]. Armstrong, E. A., Hamilton, L. T., Armstrong, E. M., & Seeley, J. L. (2014). “Good Girls”: Gender, Social Class, and Slut Discourse on Campus. Social Psychology Quarterly, 77(2), 100–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272514521220

[3]. Lupu, Y., Sear, R., Velásquez, N., Leahy, R., Restrepo, N. J., Goldberg, B., & Johnson, N. F. (2023). Offline events and online hate. PLOS ONE, 18(1), e0278511. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278511

[4]. Jing-Schmidt, Z., & Peng, X. (2018). The sluttified sex: Verbal misogyny reflects and reinforces gender order in wireless China. Language in Society, 47(3), 385–408. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0047404518000386

[5]. Ghosh, I. (2020, February 15). Ranked: The 100 Most Spoken Languages Around the World. Visual Capitalist. https://www.visualcapitalist.com/100-most-spoken-languages/

[6]. Bosson, J. K., Wilkerson, M., Kosakowska-Berezecka, N., Jurek, P., & Olech, M. (2022). Harder Won and Easier Lost? Testing the Double Standard in Gender Rules in 62 Countries. Sex Roles, 87(1-2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-022-01297-y

[7]. National Sexual Violence Resource Center. (2018). Statistics. National Sexual Violence Resource Center; NSVRC. https://www.nsvrc.org/statistics

[8]. Goblet, M., & Glowacz, F. (2021). Slut Shaming in Adolescence: A Violence against Girls and Its Impact on Their Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6657. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126657

[9]. Chandler, D., & Munday, R. (2020). Dictionary Of Media And Communication. (3rd ed.). Oxford Univ Press.

[10]. Parker, K., Horowitz, J., & Stepler, R. (2017, December 5). Americans See Different Expectations for Men and Women. Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project.

[11]. Pashang, S., Khanlou, N., & Clarke, J. (2018). The Mental Health Impact of Cyber Sexual Violence on Youth Identity. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17(5), 1119–1131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-0032-4

[12]. Zempi, I., & Smith, J. (2021). Misogyny as Hate Crime. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003023722

[13]. UN Women. (2023, March 7). Facts and Figures: Leadership and Political Participation. UN Women. https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/leadership-and-political-participation/facts-and-figures

[14]. Sevelius, J. M., Chakravarty, D., Dilworth, S. E., Rebchook, G., & Neilands, T. B. (2020). Gender Affirmation through Correct Pronoun Usage: Development and Validation of the Transgender Women’s Importance of Pronouns (TW-IP) Scale. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9525. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249525

[15]. Nations, U. (2015). Youth. United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/youth#:~:text=There%20is%20no%20universally%20agreed

[16]. Camacho, S., Hassanein, K., & Head, M. (2018). Cyberbullying impacts on victims’ satisfaction with information and communication technologies: The role of Perceived Cyberbullying Severity. Information & Management, 55(4), 494–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2017.11.004

[17]. Beyond Blue. (2021). Beyond Blue. Www.beyondblue.org.au; Beyond Blue. https://www.beyondblue.org.au/who-does-it-affect/young-people

[18]. Romer, D., & Bock, M. (2008). Reducing The Stigma of Mental Illness Among Adolescents and Young Adults: The Effects of Treatment Information. Journal of Health Communication, 13(8), 742–758. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730802487406

[19]. Adhikari, H. (2015). Limerence Causing Conflict in Relationship Between Mother-in-Law and Daughter-in-Law : A Study on Unhappiness in Family Relations and Broken Family. Multidisciplinary Journal of Gender Studies, 4(2), 739. https://doi.org/10.17583/generos.2015.1261

[20]. Lu, F. (2023, February 21). “Pink hair prostitute” taunts drive promising young Chinese woman to suicide. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/news/people-culture/trending-china/article/3210853/bullied-death-millions-chinese-mourn-after-prostitute-pink-hair-taunts-drive-woman-23-suicide

[21]. Dedeyne, S. (2020, June 2). Kairi Sane Gives Beautiful Tribute To Hana Kimura During Raw. Ringside Intel. https://ringsideintel.com/2020/06/kairi-sane-gives-beautiful-tribute-to-hana-kimura-during-raw/

[22]. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023, April 6). Suicide & self-harm monitoring. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. https://www.aihw.gov.au/suicide-self-harm-monitoring/data/data-downloads?&page=2

[23]. The World Bank. (2023). Youth 15-24. World Bank Gender Data Portal. https://genderdata.worldbank.org/topics/youth-15-24/

Cite this article

Peng,Y. (2024). Gender-Based Double Standards and Inequalities in Online Culture: Objectification of Feminine Sexuality, Self-Expression and Appearance, and Cybershaming. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,50,225-236.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Halim, M. L., Ruble, D. N., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Zosuls, K. M., Lurye, L. E., & Greulich, F. K. (2014). Pink frilly dresses and the avoidance of all things “girly”: children’s appearance rigidity and cognitive theories of gender development. Developmental Psychology, 50(4), 1091–1101. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034906

[2]. Armstrong, E. A., Hamilton, L. T., Armstrong, E. M., & Seeley, J. L. (2014). “Good Girls”: Gender, Social Class, and Slut Discourse on Campus. Social Psychology Quarterly, 77(2), 100–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272514521220

[3]. Lupu, Y., Sear, R., Velásquez, N., Leahy, R., Restrepo, N. J., Goldberg, B., & Johnson, N. F. (2023). Offline events and online hate. PLOS ONE, 18(1), e0278511. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278511

[4]. Jing-Schmidt, Z., & Peng, X. (2018). The sluttified sex: Verbal misogyny reflects and reinforces gender order in wireless China. Language in Society, 47(3), 385–408. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0047404518000386

[5]. Ghosh, I. (2020, February 15). Ranked: The 100 Most Spoken Languages Around the World. Visual Capitalist. https://www.visualcapitalist.com/100-most-spoken-languages/

[6]. Bosson, J. K., Wilkerson, M., Kosakowska-Berezecka, N., Jurek, P., & Olech, M. (2022). Harder Won and Easier Lost? Testing the Double Standard in Gender Rules in 62 Countries. Sex Roles, 87(1-2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-022-01297-y

[7]. National Sexual Violence Resource Center. (2018). Statistics. National Sexual Violence Resource Center; NSVRC. https://www.nsvrc.org/statistics

[8]. Goblet, M., & Glowacz, F. (2021). Slut Shaming in Adolescence: A Violence against Girls and Its Impact on Their Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6657. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126657

[9]. Chandler, D., & Munday, R. (2020). Dictionary Of Media And Communication. (3rd ed.). Oxford Univ Press.

[10]. Parker, K., Horowitz, J., & Stepler, R. (2017, December 5). Americans See Different Expectations for Men and Women. Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project.

[11]. Pashang, S., Khanlou, N., & Clarke, J. (2018). The Mental Health Impact of Cyber Sexual Violence on Youth Identity. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17(5), 1119–1131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-0032-4

[12]. Zempi, I., & Smith, J. (2021). Misogyny as Hate Crime. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003023722

[13]. UN Women. (2023, March 7). Facts and Figures: Leadership and Political Participation. UN Women. https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/leadership-and-political-participation/facts-and-figures

[14]. Sevelius, J. M., Chakravarty, D., Dilworth, S. E., Rebchook, G., & Neilands, T. B. (2020). Gender Affirmation through Correct Pronoun Usage: Development and Validation of the Transgender Women’s Importance of Pronouns (TW-IP) Scale. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9525. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249525

[15]. Nations, U. (2015). Youth. United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/youth#:~:text=There%20is%20no%20universally%20agreed

[16]. Camacho, S., Hassanein, K., & Head, M. (2018). Cyberbullying impacts on victims’ satisfaction with information and communication technologies: The role of Perceived Cyberbullying Severity. Information & Management, 55(4), 494–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2017.11.004

[17]. Beyond Blue. (2021). Beyond Blue. Www.beyondblue.org.au; Beyond Blue. https://www.beyondblue.org.au/who-does-it-affect/young-people

[18]. Romer, D., & Bock, M. (2008). Reducing The Stigma of Mental Illness Among Adolescents and Young Adults: The Effects of Treatment Information. Journal of Health Communication, 13(8), 742–758. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730802487406

[19]. Adhikari, H. (2015). Limerence Causing Conflict in Relationship Between Mother-in-Law and Daughter-in-Law : A Study on Unhappiness in Family Relations and Broken Family. Multidisciplinary Journal of Gender Studies, 4(2), 739. https://doi.org/10.17583/generos.2015.1261

[20]. Lu, F. (2023, February 21). “Pink hair prostitute” taunts drive promising young Chinese woman to suicide. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/news/people-culture/trending-china/article/3210853/bullied-death-millions-chinese-mourn-after-prostitute-pink-hair-taunts-drive-woman-23-suicide

[21]. Dedeyne, S. (2020, June 2). Kairi Sane Gives Beautiful Tribute To Hana Kimura During Raw. Ringside Intel. https://ringsideintel.com/2020/06/kairi-sane-gives-beautiful-tribute-to-hana-kimura-during-raw/

[22]. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023, April 6). Suicide & self-harm monitoring. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. https://www.aihw.gov.au/suicide-self-harm-monitoring/data/data-downloads?&page=2

[23]. The World Bank. (2023). Youth 15-24. World Bank Gender Data Portal. https://genderdata.worldbank.org/topics/youth-15-24/