1. Introduction

The internet, as a new communication technology, has created a fresh social environment for interpersonal interaction [1]. In online communication, individuals can interact with others without the usual constraints of time or spatial boundaries and are able to present themselves without outside interference. Such a social environment reduces the immediate feedback and pressure users receive, so that they may be more open to expressing themselves and have different word choices compared to real-life communication [2].

In the book “The Language Game”, Christiansen and Chater make a very illuminating point that language evolution is a process of improvisation, in which participants interactively construct meanings [3]. In contrast to the "transformational grammar" proposed by today's leading language theorist, Noam Chomsky, in which every language has a “deep structure” of generative rules [4], Christiansen and Chater argue that human beings construct meaning through the use of communication tools, in this case, words, to signal to each other until understanding is conveyed [3]. Therefore, humans are capable of fulfilling their needs by using rhetorical means like metaphors and puns on non-existent entities, such as the relationship between a line with another person. Paul M. Postal also mentioned in his skeptical perspective on linguistics, specifically syntax and grammar, that from the moment language is born, it must be seen as a complex unity of interrelated elements, but not assembled from elements that already exist and are generated with strict regularity [5]. The use of language is constantly evolving in order to adapt to the needs of communicators. Virtual spaces, unlike traditional social contexts, give individuals new possibilities for interaction, thus advancing the shaping of language and contributing to the development of new linguistic norms and conventions.

The way people address others, as one of the simple social skills, reflects how they build awareness of speech acts [6]. It is a complex reflection of the speaker’s linguistic preferences, cultural backgrounds, and target community. In 1995, Ben Rampton pointed out by analyzing several real-life examples that choices of words, including their phonetic features, are linked to an “institutional”, which is a larger-scale dimension of context [7]. This statement suggests that linguistic change is not arbitrary but can be related to various real-life facts associated with the audience, aims, or content of communication. By choosing a particular language use, individuals identify their belonging to different communities. These communities are influenced by other institutional factors. In the context of online communication, individuals navigate digital environments in which language choices are determined by the norms and conventions of the virtual community. The improvisational nature of online interactions enables individuals to experiment with language and adapt it to suit different dimensions of communication needs. This dynamic process of linguistic negotiation reflects the influence of institutional factors on language change and identity construction in digital environments.

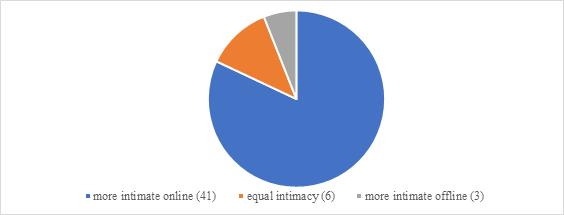

When investigating ways of addressing others among international students at Penn English Language Program (Penn ELP), this study found that more than 80 percent of the selected 50 students were more intimate online than offline (Figure 1). Using this data as a research premise, and by analyzing two representative cases in the mentioned sample, this paper aims to illustrate the mechanisms by which improvisation shapes the dynamics of online addressing. In addition, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of the evolving nature of human interaction in the digital age, emphasizing the impact of improvisation on online communication and its role in forming intimate connections in virtual spaces.

However, it is important to acknowledge that this paper has limitations since it does not fully consider the effects of factors such as cultural differences in addressing, gender dynamics, and age range on the examined phenomenon. Nevertheless, this study provides insights into language use in digital communications and sets the stage for further exploration of this intriguing topic.

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Framework

Zappa-Hollman and Duff introduced a concept called “individual network of practice (INoP)” in 2015 [8], which can be used as a language socialization research approach that focuses on the learner while also considering the rest of those who interact with them. This approach can be used to examine participants’ interactions and practices on online platforms and can give insights into how they navigate their interaction experiences and adjust their identities in the online social context.

This paper is based on data from a panel survey of “online/offline address patterns” using INoP that involved 50 international adult students at Penn ELP. Data shows that more than 80 percent of participants admit to addressing others more intimately online than in person (figure 1).

Figure 1: Slef-perspect intimacy in online/offline address patterns

Based on the above data, this study aims to dig deeper into the phenomenon of increased intimacy in online communication compared to offline interactions and its relationship with improvisation. This paper is guided by the following questions:

1) How do people tend to address others differently online and offline?

2) How are the differences in online and offline address patterns related to improvisational language practices?

3) How do the dynamics of human interaction change in the digital age?

2.2. Recruitment

This paper took a case study approach and analyzed two international adult students in the English Language Program at the University of Pennsylvania (Penn ELP). The main objectives of this case study are to explore the role of improvisational language practices in shaping intimacy on digital platforms and to understand the factors influencing the dynamics of online communication, which also provides insights into the implications for interpersonal relationships.

Table 1 below will give their specific background information.

Table 1: Participants' Background Information

Name |

Nationality |

Sex |

Age |

Commonly used online chatting platforms |

Frequency of use |

English proficiency |

Yosra |

Saudi |

F |

26 |

10 times a day, 5-10 minutes each time |

Advanced |

|

Chen |

Chinese |

F |

19 |

WeChat/ Instagram |

2-3 hours a day |

Middle to advanced |

2.3. Data Collection

The data collection of these two cases included:

1) Observational data from the two participants’ behaviors and conversations at the ELP student center and public online interactions such as comments sections of ELP websites and online workshops.

2) Textual data from the two participants’ conversations on all kinds of commonly used online platforms.

3) Data from group and one-on-one interviews. The interviews first focus on the participants’ offline discourse, and then on their online discourse. Findings from both parts will be compared to highlight the differences in addressing patterns, language improvisation strategies, and perceived intimacy levels between online and offline communication and identity constructions.

Table 2 and Table 3 below present the schedule of the interviews.

Table 2: Schedule of Group Interviews

Schedule |

Topic |

Interview Type |

Duration |

08/04/2024 |

Experiences with offline communication |

Narrative interviews |

21minutes |

16/04/2024 |

Experiences with online communication |

Narrative interviews |

18 minutes |

Table 3: Schedule of One-on-One Interviews

Schedule |

19/04/2024 |

24/04/2024 |

01/05/2024 |

08/05/2024 |

Topic |

Specific instances of address patterns online/offline, including their differences |

The aspects of online communication that contribute to increased intamacy compared to offline communication |

Ways of navigating use of language in online communication (choice of words/tone) |

The role of improvisation in shaping language use in online communication |

Interview Type |

Semi-stuctured interviews |

Semi-stuctured interviews |

Semi-stuctured interviews |

Reflective interviews |

Duration |

25 minuttes |

40 minutes |

25 minutes |

32 minutes |

2.3.1. Data Analysis

However, the limitations of this case study are the small sample size and the fact that it does not consider the impact of gender and the culture of address on this topic.

Table 4: Statistics of Yosra

|

Address patterns |

Percieved intimacy level |

Improvisation strategies |

Offline |

Direct names (always) |

Low |

/ |

Online |

Nickmames from other ones’ personalities (mostly) حبي ياحلوه (sometimes to quite close friends; similar to “baby” or “darling”, no direct translation) |

High (intimacy increases with the colseness of the relationship ) |

Be more creative and playful with language use (come up with personalized and intimate form of addresses) Sandwiching address patterns with emojis |

Table 5: Statistics of Chen

|

Address patterns |

Percieved intimacy level |

Improvisation strategies |

Offline |

Direct names (mostly) Nicknames (sometimes) |

Low |

/ |

Online |

Nicknames (mostly) Babe; Dear; wifie (very frequently used when calling female friends) |

High |

Communicate in a much more casual and informal way Linguistic borrowing from other languages (mostly English, Japanese, and Korean), signal a sense of openness Stay creative Use abbreviations (shortened versions of others’ name or personalities) |

3. Results

3.1. Differences in address patterns in online/offline communication

In face-to-face communication, both participants indicate that they mostly address others directly by their names. However, when it comes to online communication, they become much more diverse in the way they call others, for example, nicknames come up from the other’s personalities and intimate epithets that do not represent real relationships. It can be seen that online communication typically exhibits a greater sense of informality than offline interactions. Participants tend to use less formal language and address each other in a more familiar manner to enhance intimacy.

Research has shown that each individual turns out to use relatively consistent and unique behavioral characteristics in online interactions. This suggests that individuals develop unique patterns of address and communication styles that can be identified and analyzed through statistical and machine-learning techniques [8]. For individuals with complex communication needs, the use of online social platforms can have a significant impact on their search for greater inclusion [9]. The effective use of these platforms allows users to develop and maintain social connections, reduce isolation, and increase life satisfaction [10], which results in more relaxation in interpersonal interactions and more creativity in online addressing.

3.2. Factors relevant to intimacy in address patterns

Address as a discipline has been studied in several disciplines, including historical linguistics, etymology, psychology, anthropology ethnography, and philosophy. This interdisciplinary approach emphasizes the complexity and multifaceted nature of address as a linguistic and sociocultural phenomenon [11]. How people address others reflects social norms, cultural practices, and language use in different contexts, complementing sociolinguistic scholarship. In modern linguistics, address has not only been studied as a separate sociolinguistic topic. Still, it has also been explored in various subfields such as greetings, dialectology, and comparative linguistics [12]. This multifaceted approach reflects the many ways in which address is manifested in language use and social interaction.

Drawing from an interdisciplinary perspective, several main factors contribute to the phenomenon of increased intimacy in online addressing. To begin with, the relative anonymity in online communication may lead to a de-inhibition effect, whereby individuals feel less inhibited in revealing personal information or expressing emotions. This may encourage people to talk more intimately with each other, as they may not feel as concerned about potential social repercussions:

I am quite an introverted person, so when I look into other people at their eyes while talking to them, I only think of the most normal and formal way to address them. But if it is online where I do not see them, I feel more comfortable and would like to call them differently, causally. (Yosra)

Furthermore, online communication gets rid of the be geographical distances and physical barriers, which enables individuals to interact with others regardless of their location. This feature may create a sense of psychological closeness between people and lead them to be more creative in language use since they have to rely more on verbal communication to express their emotions.

I feel like addressing people directly by their names online seems too serious, so I always try to come up with some fun addresses so that other people can sense that I am in a good mood and this is a casual conversation. (Chen)

Another reason for increased intimacy in online addressing can be people’s habituation to the internet and the instinctive hope for intimacy in relationships. Humans have an innate need for social connection and intimacy in relationships. In the absence of face-to-face interaction, individuals may seek to satisfy this need through online communication, even with people they have not met in person, where they can make emotional connections and express intimacy through language [13].

3.3. The role of improvisation in online communication

In the book “The Language Game”, Christiansen and Chater suggest that language evolution is a process of improvisation instead of sticking to strict generative rules [3]. As people engage in spontaneous communication, they constantly adapt language use to convey meaning, build relationships, and respond to changing circumstances, and it is the dynamic and evolving nature of online communication environments that characterizes them [9]. To fit into such an environment, people thus employ improvisational language practices to express themselves effectively and achieve communication goals.

In addition, online verbal intimacy's significance, particularly in relationship development and identity construction on social media platforms, emphasizes self-disclosure [14]. According to social penetration theory, when individuals engage in self-discourse, they tend to share more and more personal information and ideas without putting much consideration [15], in other words, they become improvisational in communication. The more information they exchange, the deeper their connection and intimacy are with each other. It is believed that this process contributes to the closeness in relationships [13]. Thus, the unique features of online communication encourage users to expose themselves, which leads to a more open environment for language use and serves as an indicator of relationship progress and the development of intimacy.

4. Discussion

This study is based on the theory of language evolution in “The Language Game” and collected data from 50 international adult students at Penn ELP.

To begin with, this study finds that participants tend to address others differently, to be specific, more intimately, online compared to offline. By examining two case studies, the paper lists three main factors that are relevant to the phenomenon of increased intimacy in online addressing: the anonymity of online communication, the sense of distance, and the instinctive hope for intimacy. And by using the social penetration theory as a reference [15], it can be seen that these factors encourage people to exchange personal information more frequently, which results in the improvisation in communication and increased intimacy in language use.

5. Conclusion

This paper draws on insights from “The Language Game” and explores the dynamics of intimacy in online addressing. By examining the role of improvisation in online communication, the study shows subtle ways in which individuals cultivate intimacy in digital environments through spontaneous and improvisational language practices that enrich their online interactions and create deeper connections with others.

The study demonstrates the impact of the Internet on interpersonal interactions by providing individuals with opportunities to connect and communicate across time and space. In this new social environment, individuals are liberated from the constraints of traditional communication and are able to express themselves more with diverse linguistic options. The concept of improvisation, however, is the driving force behind the evolution of language in online communication. Contrary to traditional views of language structure and grammar, we believe that people construct meaning through interactive communication and adapt language to meet their communication needs. This improvisational approach emphasizes the fluid nature of language use in digital environments, where individuals constantly negotiate expression and identity through language use. On the other hand, this paper acknowledges certain limitations in aspects such as cultural differences, gender, and age, these factors need further exploration to reach more comprehensive understanding of language practices and online communication dynamics.

References

[1]. Hirdman, A. (2010). Vision and intimacy. Nordicom Review, 31(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1515/nor-2017-0117

[2]. Labrecque, L. I., Markos, E., & Darmody, A. (2019). Addressing online behavioral advertising and privacy implications: A comparison of passive versus active learning approaches. Journal of Marketing Education, 43(1), 43–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475319828788

[3]. Christiansen, M. H., & Chater, N. (2023). The language game: How improvisation created language and changed the world. Transworld.

[4]. Chomsky, N. (1997). Transformational analysis. UMI Dissertation Services.

[5]. Paul M. Postal. (2013). Sceptical Linguistic Essays. The Anti-Chomsky Reader. San Francisco: Encounter Books. URL: http://linguistics.as.nyu.edu/object/PaulMPostal.html

[6]. Alptekin, C. (2002). Towards intercultural communicative competence in ELT. ELT Journal, 56(1), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/56.1.57

[7]. Rampton, B. (2020). Language crossing and the problematisation of ethnicity and socialisation 1. The Bilingualism Reader, 177–202. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003060406-19

[8]. Adeyemi, I. R., Razak, S. A., Salleh, M., & Venter, H. S. (2016). Observing consistency in online communication patterns for user re-identification. PLOS ONE, 11(12). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0166930

[9]. Bosse, I., Renner, G., & Wilkens, L. (2020). Social Media and internet use patterns by adolescents with complex communication needs. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 51(4), 1024–1036. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_lshss-19-00072

[10]. Cooper, L., Balandin, S., & Trembath, D. (2009). The loneliness experiences of young adults with cerebral palsy who use alternative and augmentative communication. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 25(3), 154-164. https://doi-org.proxy.library.upenn.edu/10.1080/07434610903036785

[11]. Braun, Friederike. Terms of Address : Problems of Patterns and Usage in Various Languages and Cultures /. Berlin ; New York : Mouton de Gruyter, 1988. Web.

[12]. Kraska-Szlenk, I. (2018). Address inversion in Swahili: Usage patterns, cognitive motivation and cultural factors. Cognitive Linguistics, 29(3), 545–583. https://doi.org/10.1515/cog-2017-0129

[13]. Lin, Y.-H., & Chu, M. G. (2021). Online communication self-disclosure and intimacy development on Facebook: The perspective of uses and gratifications theory. Online Information Review, 45(6), 1167–1187. https://doi.org/10.1108/oir-08-2020-0329

[14]. Hu, Y., Wood, J.F., Smith, V. and Westbrook, N. (2004), “Friendships through IM: examining the relationship between instant messaging and intimacy”, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Vol. 10 No. 1.

[15]. Altman, I. and Taylor, D.A. (1973), Social Penetration: The Development of Interpersonal Relationships, Holt, Rinehart & Winston, New York, NY.

Cite this article

Zhang,T. (2024). Intimacy Unbound: Exploring the Role of Improvisation in Online Communication and Its Influence on Address Patterns. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,54,278-284.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Education Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Hirdman, A. (2010). Vision and intimacy. Nordicom Review, 31(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1515/nor-2017-0117

[2]. Labrecque, L. I., Markos, E., & Darmody, A. (2019). Addressing online behavioral advertising and privacy implications: A comparison of passive versus active learning approaches. Journal of Marketing Education, 43(1), 43–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475319828788

[3]. Christiansen, M. H., & Chater, N. (2023). The language game: How improvisation created language and changed the world. Transworld.

[4]. Chomsky, N. (1997). Transformational analysis. UMI Dissertation Services.

[5]. Paul M. Postal. (2013). Sceptical Linguistic Essays. The Anti-Chomsky Reader. San Francisco: Encounter Books. URL: http://linguistics.as.nyu.edu/object/PaulMPostal.html

[6]. Alptekin, C. (2002). Towards intercultural communicative competence in ELT. ELT Journal, 56(1), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/56.1.57

[7]. Rampton, B. (2020). Language crossing and the problematisation of ethnicity and socialisation 1. The Bilingualism Reader, 177–202. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003060406-19

[8]. Adeyemi, I. R., Razak, S. A., Salleh, M., & Venter, H. S. (2016). Observing consistency in online communication patterns for user re-identification. PLOS ONE, 11(12). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0166930

[9]. Bosse, I., Renner, G., & Wilkens, L. (2020). Social Media and internet use patterns by adolescents with complex communication needs. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 51(4), 1024–1036. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_lshss-19-00072

[10]. Cooper, L., Balandin, S., & Trembath, D. (2009). The loneliness experiences of young adults with cerebral palsy who use alternative and augmentative communication. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 25(3), 154-164. https://doi-org.proxy.library.upenn.edu/10.1080/07434610903036785

[11]. Braun, Friederike. Terms of Address : Problems of Patterns and Usage in Various Languages and Cultures /. Berlin ; New York : Mouton de Gruyter, 1988. Web.

[12]. Kraska-Szlenk, I. (2018). Address inversion in Swahili: Usage patterns, cognitive motivation and cultural factors. Cognitive Linguistics, 29(3), 545–583. https://doi.org/10.1515/cog-2017-0129

[13]. Lin, Y.-H., & Chu, M. G. (2021). Online communication self-disclosure and intimacy development on Facebook: The perspective of uses and gratifications theory. Online Information Review, 45(6), 1167–1187. https://doi.org/10.1108/oir-08-2020-0329

[14]. Hu, Y., Wood, J.F., Smith, V. and Westbrook, N. (2004), “Friendships through IM: examining the relationship between instant messaging and intimacy”, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Vol. 10 No. 1.

[15]. Altman, I. and Taylor, D.A. (1973), Social Penetration: The Development of Interpersonal Relationships, Holt, Rinehart & Winston, New York, NY.