1. Introduction

In the early days of the K-pop music industry (what we have come to refer to as the ‘first generation’ or ‘second generation’), most girl groups centered their concepts on the intensely sexy or soft-spoken, pretty-faced girl [1], presenting an image of powerlessness and thus dependence and submission to men in discourses of love or affection. The gender segmentation of K-pop fans, especially heterosexuality, has traditionally been much more divided. Male groups typically make up the majority of the female fandom, while female group followers tend to skew male. This gender division gives male groups an advantage in terms of longevity [2]. As a result, girl groups have created the concept of the “girl crush” in order to appeal to a wider public. In the third generation of girl groups, there are many female creators who are trying to break the stereotypes of female roles in the patriarchal gaze [3]. Meanwhile, some research found that K-pop music is trying to communicate to fans around the world the idea of women’s performance of gender melancholy owing to sexism, and that gender melancholy is resulting in the female around the world to become involved in K-pop’s fandom [4].

(G)I-DLE is K-pop girl group launched in 2018 by CUBE Entertainment, consisting of five members, Soyeon, Minnie, Miyeon, Yuqi, and Shuhua (and initially Soojin, who later withdrew for personal reasons). They stand out in the highly competitive K-pop industry with their strong creative girl group orientation and diverse musical styles. (G)I-DLE’s music, which is mostly composed by the members themselves under the leadership of leader Soyeon, is more personal and artistic, and shows concern for social issues such as women’s power, identity, and self-worth.

Many researchers have explored how feminism in the structure of the K-pop industry seems to apparently achieve the promotion and advocacy of female empowerment. However, it still reinforces the gender norms of the patriarchal gaze structure of stereotypical women in reality [5]. It’s essential to explore the subjective ideas that female creators seek to convey through their work by focusing on the song “Nxde” and the related perspectives derived from it to deconstruct it in the context of the typical patriarchal gaze structure of K-pop.

2. Background Research

The case from the (G)I-DLE presents a compelling case for exploring feminist expression within the K-pop industry. Their song “Nxde” challenges the conventional portrayal of women in visual media and offers an alternative model of female creativity and subjectivity. Written by the group’s leader, Soyeon, the song is grounded in the belief that “ I’d rather be hated than pretend to be my true self.” This philosophy highlights the tension between authenticity and marketability in a highly commercialized industry. Despite initial skepticism from some company insiders, Soyeon and her groupmates pushed forward with the project, crafting a song that critiques the sexualization of women and regressive beauty standards.

It is evident from the operational structure of entertainment companies in the K-pop industry that the music and concepts of the overwhelming majority of idol groups are controlled by the companies [6]. Within this framework, idols are subjected to a carefully crafted image created through packaging and marketing strategies, often leading to a loss of personal creative agency. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced for female idols, whose representation in visual media tends to be overtly commodified. Their images are frequently designed to be either sexy or cute, catering to the male gaze and reinforcing stereotypical gender roles. This not only limits the subjectivity of female creators but also perpetuates the objectification of women in popular culture.

Against this backdrop, (G)I-DLE stands out with their bold attempt to redefine female representation through their song “Nxde”. The song was written by the group’s leader, Soyeon, based on the philosophy, “I'd rather be hated than pretend to be my true self.” Despite initial resistance from some insiders within the company, the song was officially released. Soyeon, together with her teammates, challenges the sexualization of women and the regressive notions of beauty through a playful and ironic lens. The song and its associated concepts aim to subvert the traditional patriarchal portrayal of women, showcasing the group’s independent creative vision.

The creation and release of “Nxde” demonstrate (G)I-DLE’s unique approach to feminist expression in a commercialized pop culture framework. For instance, the song’s promotional campaign drew attention with its provocative imagery but ultimately defied expectations through its satirical critique of female objectification. The music video deepened this critique by employing visually striking styles, paying homage to iconic female figures, and innovating with camera techniques to reframe the narrative around female identity. Meanwhile, the song’s societal reception exposed the tension between feminist ideals and the commercial realities of the K-pop industry.

3. Literature Review

Existing studies have examined feminist expressions within the K-pop idol industry from three main perspectives.

First, researchers have examined the cultural and structural aspects of the K-pop industry, including the growth of fandom culture, worldwide cultural export initiatives, and idol training systems [7]. One of South Korea's most notable cultural exports today is the idol industry, and the fandom culture that surrounds it is crucial in determining how K-pop idols are viewed and promoted. When idols' representations adhere to patriarchal and commercial norms, fandoms can complicate the story of feminist expression. Fandoms frequently increase the exposure of idols while also contributing to the cultural construction of meaning surrounding their image.

Second, semiotic analysis has been employed to decode the symbolic meanings of female bodies within song lyrics and music video representations, highlighting how K-pop has engaged with or reinforced gender norms. These studies review how women’ s bodies have been aestheticized, sexualized, and contextualized within the framework of patriarchal media. The evolution of female body symbols in K-pop has been the main focus, showing a tendency that swings between empowerment and commodification. Such studies emphasize the role of visual and lyrical storytelling in either sticking or challenging traditional gender roles, which often reduces female idols to objects of male pleasure.

Third, critical studies have delved into the commodification of gendered identities within the K-pop industry. Companies oversee every aspect of an idol’s career, including their public image, music production, and marketing strategies, leaving little room for idols to exercise creative autonomy. Female idols are particularly affected by this control, as their visual and artistic representations are often aligned with marketable stereotypes of “sexiness” or “cuteness”. These images are designed to appeal to the male gaze, thereby reinforcing patriarchal norms and limiting female idols’ ability to articulate their own identities.

Therefore, the analysis will take (G)I-DLE’s “Nxde” as a case study to explore female subjectivity and creativity in the K-pop industry. By examining the song’s promotional strategies, music video, lyrics, and societal reception, this research investigates whether female creators in this highly commercialized industry can achieve visual pleasure from a female perspective and challenge the male subject’s dominance. This analysis not only addresses the feminist discourse within the K-pop industry but also contributes to broader discussions on women’s autonomy and creative expression in the entertainment industry.

4. Analysis

4.1. Ideological Infiltration of Promotion and Arrangement: Nakedly Fraudulent

During the promotional phase of “Nxde”, the teaser video cleverly utilized the element of sex to attract attention, but its core intention was to reverse the audience's expectations and reveal an attitude of rejection of the male gaze. By using sexy visual elements in reverse, the teaser video sends a warning to viewers who are looking for purely gendered performances: if you are expecting “traditional sexy performances”, then please “go out and turn left”. This approach not only breaks the boundaries between reality and the fictional world of the music video, but also symbolically “fraudulent” the audience of their expectations, and at the same time gives them a deep sense of criticism and reflection, both visually and intellectually.

The arrangement of “Nxde” skillfully samples the aria “Love is a Free Bird” from the opera Carmen, combining the opera's image of the free, uninhibited woman with the modern notions of gender in popular culture. Carmen, as the classic gypsy girl female figure in art history, represents a challenge to traditional female roles. Introducing this element into the song emphasizes the artist’s pursuit of freedom, independence and female autonomy, and at the same time echoes the “naked” treatment of the female figure in the song title and music video, in an attempt to redefine the value and way of existence of the female figure, and thus question the traditional gendered gaze [7].

4.2. Multiple Deconstructions of the Music Video and Lyrics: Backlash and Reinvention

4.2.1. Under the Red Curtain: Scene Construction for Playfulness and Extravagance

(a) |

(b) |

(c) |

Figure 1: The clips from the music video “Nxde”.

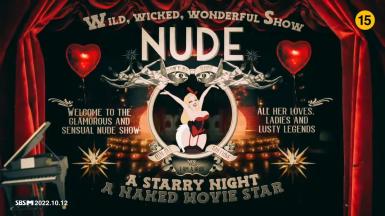

The main logo design from Figure 1 comes from Metro Goldwyn Mayer, which is a classic lion brand, around the advertising slogan naked and direct, the atmosphere ambiguous and eye-catching, while the slender body of the woman instead of the original lion makes a big show opening pose to welcome the audience.

It is a controversial poster surrounded by words like NUDE, WILD, WICKED, WONDERFUL. Afterwards, the woman is in the poster as objects to be gazed at and viewed in order to attract as well as please the people who want to come to see the nude show. These people are in fact the beneficiaries of patriarchal power.

The scene can be seen in Figure 1, showing the classic Moulin Rouge style. In the early 20th century France, heroine Satine because of the financial crisis of the Moulin Rouge had to sacrifice themselves, pretending to fall in love with the Duke, and can only be forced to refuse to love their own songwriter Christian. finally, the incense is gone, and fell asleep on the stage forever. Perhaps in the eyes of The Duke and Christian, what they saw was Satine’s beauty and charm, while Satine sacrificed herself for the Moulin Rouge and Christian’s music. Women seem to always be passive, sacrificed, and chosen roles. As the red curtain opens, the set and lighting design is very gold and luxury, full of golden and red light, but revealing a tragic atmosphere. The stage was opulent and surreal, and the flapper girls’ red dresses blended in with their surroundings, revealing an atmosphere of unbelievable extravagance.

4.2.2. Deconstructing the Classics: Homage and Reinvention of the Female Image

Figure 2: The clips from the music video “Nxde”.

In Figure 2, the scene pays homage to the clip of Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend sung by Marilyn Monroe’s character in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. The movie's portrayal of Marilyn Monroe carries over the original's cliché of the goofy blonde, an artificial simplicity imposed by the audience's expectations and fantasies about Monroe [8]. The impression of a fun and adorable foolhardy beauty is revealed by the artist's aqua velvet fabric, striking and shining diamond accessories, and the enormous bow at the rear of the waist, in addition to her distinctively lovely voice.

‘Hello my name is yeppi yeppi.

Slightly dumb the way I talk, but I’ve got a sexy, sexy figure.

Well, for a tiara with a diamond.’

(lyrics from Nxde)

One can sense the artist's attempt in the lyrics of this clip to depict a sexy, nude woman as a microcosm of the orientation of most of the viewers who are captivated by the opening curtain, the values of vanity, beauty, and stupidity, which are not the constraints imposed on women by the patriarchal gaze, without exception.

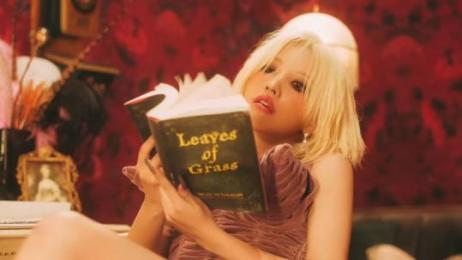

Figure 3: The clips from the music video “Nxde”.

The shape pays homage to Madonna’s classic shape spiked bra in Figure 3. Meanwhile, this kind of conical corset is also because of Marilyn Monroe rise, is her favorite type of underwear at that time. The book in her hand is a collection of poems written by American poet Walt Whitman that Marilyn Monroe loved, who often explores life, self and nature, and proclaims the beauty of flesh and sexuality, with a novel, bold and free style of poetry [9].

‘Twisted lorelei that don't need no man.

A bookworm obsessed with philosophy, a self-made woman.’

(lyrics from Nxde)

The Lorelei mentioned in the lyrics refers to a rocky outcrop on the Rhine River, where it is said that a young girl threw herself into the river because of her lover’s unfaithfulness, and after her death, she turned into a water demon and sat on the rock, singing as she lured the boatman to touch the reef and sink the boat. The philosophy-obsessed nerd remains a tribute to Marilyn Monroe’s essential pursuit of literature, and also callbacks the book Leaves of Grass embodied in the music video.

Obviously is a lady who had a special passion for reading and very have their own female independent thinking of women, Marilyn Monroe has been in the public mind image why has been with beauty, vanity, fools these labels, until now with the awakening of women’s consciousness continue to rehabilitate.

(a) |

(b) |

(c) |

Figure 4: The clips from the music video “Nxde”.

Is this a human being or a work of art? The artist’s form in Figure 4 is a heavily embellished, ivory-white miniature dress, like a sculpture placed in an upscale auction house, observed with a magnifying glass for details, and then auctioned off after being observed. The ostentatious poses are a protest against the limitations of the deformed female body and mind under the male gaze, as well as a protest against the pricing and consumption of the female body, and a protest against the ego’s need to break free of stereotypes and constraints.

‘Excuse me, to all of you who are sitting here.

If you were expecting some rated r show.

Oh I'm sorry, but that's not what we're showing.

For a refund, see that direction, whatever people say is not my interest.’

(lyrics from Nxde)

The lyrics are a warning to those who are drawn to the show because they saw the opening credits or the poster Welcome to the Naked Girl Show. The show that the artist has set up in the music video is not really about looking at naked women, and there is still time to exit the show if you want to, but if you stay any longer you will only be hurt by the insights that the world of the music video is trying to convey afterward.

This is about the objectification of women. Being auctioned off as a work of art is in fact an allusion to the commodification of K-pop girl groups in the entertainment industry, i.e. through packaging concepts and marketing styles to attract different audiences to pay for their consumption. This is why it has been difficult to explore the contradictions between K-pop girl groups and feminism. There is no difference in the nature of female idols and female dancers in the eyes of the patriarchy.

4.2.3. Protest in the language of the camera: montage and the deconstruction of viewing

(a) |

(b) |

(c) |

(d) |

(e) |

(f) |

(g) |

(h) |

Figure 5: The clips from the music video “Nxde”.

The visual contrast brought by different frames and colors is very clearly shown from Figure 5. 16:9, a successful successor specification, is now used in high-definition and digital television, while the traditional 4:3, an early cinematic ratio, serves to expand narrative time and space, and the wide format tends to deliver more visual information as well as a wider environmental space [10].

‘Even if I look tacky or perhaps to you.

Even if I'm not loved anymore.’

‘Ah, an undressed movie star .

Ah, a night of broken starlight.’

‘Baby how do I look? how do I look?’

(lyrics from Nxde)

Lyrically, the snippets serve as the bridge and chorus of the song, with the 16:9 aspect ratio corresponding to images that build up to the climax as if entering an eternal night or stripping off one by one to literally become naked before moving on to the climax. The 4:3 aspect ratio corresponds to the climax, where K-pop is often repeated over and over again in order to achieve popularity [11], with the artist shouting “yes I’m a nude” to the audience and asking them. “baby how do I look”, to return to the most feminine of women when they are already bleak and ruined and no longer loved.

These four units of clips are representative of the contrast between different frames of the same look in the music video, which emphasis the use of montage. 4:3 format mimics the style of filming in the last century, where the image is black and white with no color, and in order to increase the effect of eye-catching, high contrast colors are usually used, for example, red dresses and black dresses versus blonde hair and blue eyes. 4:3 format creates a lot of restriction compared to the 16:9 format, which seems to place the women in the camera in the position of an object, observing them as a third party and even evaluating and criticizing them. The 4:3 frame is much more restrictive than the 16:9 frame, as it puts the women in the camera in the position of an object, observing, gazing, even evaluating, and criticizing them as a third party, while the 16:9 frame is more of a breaking of the shackles, as the figures are trying to break free from the patriarchal gaze and downwardly free themselves. But even though times have changed, some people’s colored glasses for nudes remain unchanged.

4.3. Social Reaction: The Game of Rebellion and Acceptance

“Nxde” has been associated with undesirable search content such as child pornography on the Internet. According to interviews with members of (G)I-DLE, the artists named the song “Nxde” in order to utilize his social influence as well, turning the content that could be searched for by the original undesirable keywords into media articles, promotional pictures and music videos , stage photos, broadcast screenshots, album and song information, and other information related to (G)I-DLE’s “Nxde”. In fact, just as they had anticipated, the release of “Nxde” pushed (G)I-DLE onto the search wave, with the keyword (G)I-DLE’s “Nxde” replacing undesirable keywords such as “child pornography”, and the power of female creators being utilized to fight against the “Nxde” of (G)I-DLE. Meanwhile, it’s positively impacted the search function of social media portals with the power of female artists.

“Nxde” redefines the image of women through artistic means, transforming “nudity” into a visual reflection that conveys resistance to the male gaze. However, the sexy make-up and commercialized image of the music video still aroused discussions among feminists. On the one hand, female creators demonstrate a challenge to the traditional image of women through this highly artistic rebellion; however, on the other hand, the gendered makeup and clothing still maintains a certain amount of marketable demand and an element of catering to male consumption. This contradiction reveals the difficult balance between the pursuit of artistic expression and the commercial market for female creators in the modern entertainment industry.

5. Conclusion

As a bold attempt by (G)I-DLE, “Nxde” proposes a profound reflection on the patriarchal gaze through the multiple deconstructions of the promotional strategy, the music video and lyrics, and the social repercussions after its release. The reversal strategy in the preview stage and the sampling of the classic image of free women in the arrangement show the creator’s independent stance with mockery and subversion as weapons. The music video, in its layering of stylized scenes, homage to classics and camera language, dismantles the limits of the patriarchal gaze on the female figure, pushing the meaning of “gaze” to the boundary of contradiction. The social repercussions of the final work, from the heat of the topic to the discussion of feminism, to the public’s reexamination of beauty and “nudity”, also reveal the complex tensions and challenges faced by female creators in the contemporary K-pop industry.

Although “Nxde” attempts to deconstruct the visual pleasure of the male subject through playfulness and irony, the stage and makeup of its songs are still not free from the controversy of sexiness and “pandering to men”. This contradiction reflects the structural dilemma faced by creative female groups in the K-pop industry - the female idol is both the creator and the object of corporate packaging and commodification. This makes it difficult for the creator’s female perspective to completely dissolve the male subject’s desire to watch, but rather manifests itself more as a dissociation and challenge to this gaze.

By analyzing the case, it is clear that the efforts of female creators have injected a more distinctly feminist color into mainstream iconoclastic culture. However, it still requires a more permanent artistic practice to truly realize the breakthrough of the patriarchal gaze structure and the dissolution of the male gazing gaze. Women’s voicing while being watched is gradually changing the boundaries of gender narratives, but the elimination of the male subject's visual pleasure remains an unfinished but worthwhile proposition for continued exploration.

References

[1]. Zhang, R. (2023). The Awakening of Female Consciousness: Study on K-Pop Girl Groups' Music Videos.

[2]. Kelley, C. (2018). How 'Girl Crush' Hooked Female Fans and Grappled With Feminism as K-pop Went Global in 2018. billboard. com.

[3]. Li, Shu Yan. (2023). Reconstruction of female body symbols in Korean popular music. Journalism and Communications, 11, 1043.

[4]. Oh, I. and Kim, K.-J. (2022). Gendered melancholia as cultural branding: fandom participation in the K-pop community. Asia Pacific Business Review, 29(5), pp. 1300- 1323. doi: 10.1080/13602381.2022.2145007. 1323. doi: 10.1080/13602381.2022.2145007.

[5]. Kim, G. (2019). Neoliberal feminism in contemporary South Korean popular music: Discourse of resilience, politics of positive psychology, and female subjectivity. Journal of Language and Politics, 18(4), 560-578.

[6]. Cho, J., Bian, Y., & Lee, J. (2023). Leading digital business model transformation in the K-pop industry: the case of SM Entertainment. Asia Pacific Business Review, 29(5), pp. 1394-1424. https://doi-org-s.elink.xjtlu.edu.cn:443/10.1080/13602381.2023.2229761

[7]. Qiu, Z. (2024). Feminist Endeavors in the Visibility Economy: A Case Study of the Idol Industry-(G) I-DLE's. Media and Communication Research, 5(1), 111- 114.

[8]. Wagner, J. M. (2023). Empowerment narratives, Marilyn Monroe, and "Diamonds are a girl's best friend": a survey. Feminist Media Feminist Media Studies, 23(7), 3483-3497. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2022.2117837

[9]. Barrios, R. (2023). On Marilyn Monroe : An Opinionated Guide. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197636114.001.0001

[10]. Cai, Haibo. (2019). Exploring the aesthetic value of multi-frame scale films. Sound and Screen World / Voice and Screen World, 1, 44-45. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1006-3366.2019.01.021

[11]. Lee, K. S. Y., & Chang, M. H. (2019). Analysis of global success factors of K-pop music. Journal of Korea Entertainment Industry Association, 13(4), 1-15.

Cite this article

Zeng,Z. (2025). Feminism That Grows Itself Inside the Structure of the Patriarchal Gaze: A Case Study of the K-pop Female Creator Group--(G)I-DLE’s “Nxde”. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,82,46-54.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Zhang, R. (2023). The Awakening of Female Consciousness: Study on K-Pop Girl Groups' Music Videos.

[2]. Kelley, C. (2018). How 'Girl Crush' Hooked Female Fans and Grappled With Feminism as K-pop Went Global in 2018. billboard. com.

[3]. Li, Shu Yan. (2023). Reconstruction of female body symbols in Korean popular music. Journalism and Communications, 11, 1043.

[4]. Oh, I. and Kim, K.-J. (2022). Gendered melancholia as cultural branding: fandom participation in the K-pop community. Asia Pacific Business Review, 29(5), pp. 1300- 1323. doi: 10.1080/13602381.2022.2145007. 1323. doi: 10.1080/13602381.2022.2145007.

[5]. Kim, G. (2019). Neoliberal feminism in contemporary South Korean popular music: Discourse of resilience, politics of positive psychology, and female subjectivity. Journal of Language and Politics, 18(4), 560-578.

[6]. Cho, J., Bian, Y., & Lee, J. (2023). Leading digital business model transformation in the K-pop industry: the case of SM Entertainment. Asia Pacific Business Review, 29(5), pp. 1394-1424. https://doi-org-s.elink.xjtlu.edu.cn:443/10.1080/13602381.2023.2229761

[7]. Qiu, Z. (2024). Feminist Endeavors in the Visibility Economy: A Case Study of the Idol Industry-(G) I-DLE's. Media and Communication Research, 5(1), 111- 114.

[8]. Wagner, J. M. (2023). Empowerment narratives, Marilyn Monroe, and "Diamonds are a girl's best friend": a survey. Feminist Media Feminist Media Studies, 23(7), 3483-3497. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2022.2117837

[9]. Barrios, R. (2023). On Marilyn Monroe : An Opinionated Guide. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197636114.001.0001

[10]. Cai, Haibo. (2019). Exploring the aesthetic value of multi-frame scale films. Sound and Screen World / Voice and Screen World, 1, 44-45. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1006-3366.2019.01.021

[11]. Lee, K. S. Y., & Chang, M. H. (2019). Analysis of global success factors of K-pop music. Journal of Korea Entertainment Industry Association, 13(4), 1-15.