1. Introduction

Romantic relationship has been one of the most important topics in the academic field, which also make up a great proportion of everyone's life. It is a complicated interaction among human beings including but not limited to establishing emotional connections and solving conflicts. Consequently, digging deep into the factors that influence how people form their romantic relationship may help us have a better life and provide some useful data to the study field. Nowadays, especially in China, the divorce rate has increased significantly between 2000 and 2019 [1]. After releasing the policy of cooling-off period, the divorce rate takes a turn for the better. However, the situation is still not optimistic, which means that the relationship between biological parents is not good. A large number of parents will have conflicts and quarrels before their children. What’s worse, they may accuse that it is their children that make them to sustain their marriage though they want to divorce, which make their kids feel guilty. Meanwhile, the attitudes towards romantic relationships of young adults have varied greatly [2]. They have their own thoughts which are quite different from the traditional ones in China. Some of them believe that they will be solo for their whole life and have a negative attitude towards romantic relationships. Others are strongly longing for a long term partner and believe in love. With the phenomenon of increasing divorce rates and the ongoing debate of romantic relationships among young adults, we wonder if there is a relation between these two factors. To be more specific, we are curious whether the interaction of parents will influence the romantic expectations of young adults. Also, we expand our question and investigate how the difference of ages and gender influence romantic relationships and the qualities that people seek in their future partner.

2. Literature review

Understanding the impact of parental behaviors on children's development is a crucial area of psychological research. The patterns of interaction between parents are critical in shaping children's perceptions of interpersonal relationships. For example, positive and affectionate exchanges between parents provide a stable emotional environment, which is likely to foster positive expectations for future romantic relationships among their children.

This study is focused on how parental behaviors influence young adult’s romantic expectations. Social Learning Theory [3] suggests that children can learn behaviors and form expectations by observing the actions and interactions from their parents. The theory suggests that children who frequently witness positive emotional expressions between their parents, such as affection and support, are more likely to internalize these behaviors and develop similar expectations in their own romantic relationships. Attachment Theory [4] explains how early interactions with caregivers influence an individual’s expectations and behavioral patterns in future relationships. The quality of the attachment formed between children and their caregivers during childhood affects their ability to establish healthy, secure relationships in adulthood.

The impact of parental interactions on children's romantic expectations has been examined in several studies. Jamison and Lo [5] highlighted the significance of parents as role models. The study emphasizes parents’ crucial role in teaching children how to express and perceive positive emotions in romantic relationships. Their findings suggest that young adults who frequently observe positive interactions between their parents are more likely to hold optimistic views about romantic relationships. Additionally, Chen, Fan, and Zhang [6] explored the subjective experience of parental marital relationships. Their study found that children who view their parents' relationships negatively often carry these negative expectations into their own romantic relationships. The negative may further lead to greater lack of confidence about the successful romantic relationships expectations may further lead to greater lack of confidence about the successful romantic relationships. This finding supports the idea that the emotional environment created by parents can have long-term effects on their children's romantic expectations. Einav [7] found that children who perceive their parents' relationship is supportive will have higher expectations of intimacy and emotional support in their own romantic relationships. It is suggested that a positive parental relationship can influence children's immediate emotional well-being and also shape their long-term romantic expectations. Feldman et al. [8] found a direct link between parental marital satisfaction and children's ability to form close, intimate relationships in adulthood. Their study underscores the crucial role of parents’ positive communication in the future success of children's romantic relationships. Moreover, Cui and Fincham [9] noted that young adults who observed strategic conflict resolution and frequent positive interactions between their parents were more likely to believe in the feasibility of healthy, supportive romantic relationships in future.

While the existing literature provides valuable insights, several gaps remain. Most studies focused on the negative outcomes for children in high-conflict or divorced families and often overlook the role of positive emotional expressions in intact families. Much of the existing research has concentrated on children's experiences, whereas this study aims to explore expectations. Understanding the effect of a variety of factors on young people’s romantic expectations can offer predictive insights into how children navigate their romantic relationships. This study seeks to fill existing gaps by investigating how positive emotional expressions between parents in intact families, as one factor, influencing young adults' romantic expectations. By focusing on expectations rather than on experiences, this research offers a predictive perspective on the intergenerational transmission of relationship dynamics.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample

The sample used in the study were 173 participants, consisting of 51 males, 121 females, and 1 participant who preferred not to provide his gender. All participants aged between 14 and 28, in which about 22% were between the ages of 14-16 and around 57% were between the ages of 17-20. In order to analyze data effectively, participants were divided into six groups based on the frequency participants stayed with their biological parents each week. The criteria for exclusion are participants who rarely, never, and only live with one of their biological parents within one week. This refinement yielded a final number of 116 pieces of valid feedback from participants (38 males and 78 females). The purpose of this selection was to ensure that the participants lived in an environment where their parents had sufficient interactions to influence their views and perspectives. This approach allowed us to focus on individuals who experienced significant parental interactions, thereby providing more relevant data for our study. Additionally, participants were not informed of the complete aim of the research.

3.2. Measures

All data gathered in this study was obtained through a questionnaire. The questionnaire used for data collection is designed to explore several covariables: age, gender, parental interactions, qualities young people seek in their future partners and young people's perspectives on romantic relationships. The whole questionnaire was divided into five sections, each consisting of closed-ended questions, which allowed for a comprehensive analysis of how parental interactions influence young people's romantic expectations, with variations analyzed across age and gender.

3.2.1. Demographic information

This section contained three multiple choice questions which asked the participants to provide their age, gender and the frequency with which they stayed with their parents. These questions provided essential demographic context, offering background information on each participant.

3.2.2. Parents’ relationship

A total number of four closed questions were composed in this section, assessing participants' perceptions of their parents' relationships and the potential impact on the participants themselves. The questions measured aspects in parental relationships, such as the expression of positive emotion/act, the expression of negative emotion/act, and the overall quality of the relationship of the participants' biological parents. Responses were provided on 5-point rating scales with scores ranging from 1 to 5. The higher the score participants obtained in this section, the better the relationship between their parents. Therefore, we categorized the quality of parental relationships based on the participants' responses to specific questions in this part of the survey. If participants answered "often" or "always" to both Question 4, "How often do you see your biological parents expressing positive emotions toward each other?" and Question 5, "On average, how often do you see your biological parents hugging, kissing, or other acts of love in one month?" , they were classified as having parents with a relatively great relationship. Conversely, if participants responded "often" or "always" to both sub-questions of Question 6, specifically 1) "How often do you see your biological parents arguing or expressing negative emotions with each other?" and 2) "How often do your biological parents talk badly about each other to you?" they were categorized as having parents with a relatively poor relationship.

3.2.3. Expected qualities

This section includes solely one question with ten 3-item subscales, each tapping a different attribute that young individuals prioritize when envisioning their ideal partner, including intelligence, appearance, personality, humor, responsibility, emotional value, mental maturity, adventurousness, and integrity. Responses were provided on 3-point rating scale, with 1 representing not at all important and 3 representing very important.

3.2.4. Expectations for romantic relationships

Participants completed nine closed questions in this section, providing information about their perspectives towards different aspects of romantic relationships. Aspects examined in this section were namely positive expectations, faithfulness, the desire to get married, willingness to make a lifelong commitment, willingness to invest time and energy, confidence to maintain a healthy relationship, belief that relationship needs effort and commitment from both parties, and the prediction of frequency of conflicts. Usable data were collected using 5-point Likert scales and 5-point rating scale, with lower score representing a stronger disagreement and higher score representing a stronger agreement.

3.2.5. Self-rate influence

The final section contained three Likert scales, measuring factors that influence young people’s view and attitudes towards romantic relationships. This section provided deeper insights into the personal viewpoints of the participants and the degree to which parental relationships shape their romantic expectations.

3.3. Procedure

After completing the design of an online questionnaire on a Chinese website called Wenjuanxing, our research group sent the QR code of our questionnaire through WeChat. Participants joined the study by scanning the QR code. This was called volunteer sampling, which enabled our research group to collect responses from a large number of young people.

4. Results

4.1. Data analysis

For the data obtained from the questionnaire survey, this paper utilizes the Questionnaire Star quantitative data analysis software and Excel for statistical analysis.

4.2. Findings

Figure 1 presents a correlation graph depicting the relationships among the variables. On the left side, the three co-variables—age differences, gender differences, and parental interaction—are connected to the two co-variables on the right, which are young people's perspectives toward romantic relationships and the qualities young people seek in their future partner. This graph visually demonstrates how these factors interrelate, offering insights into the influences shaping young people's attitudes and preferences in romantic contexts.

4.2.1. Age differences

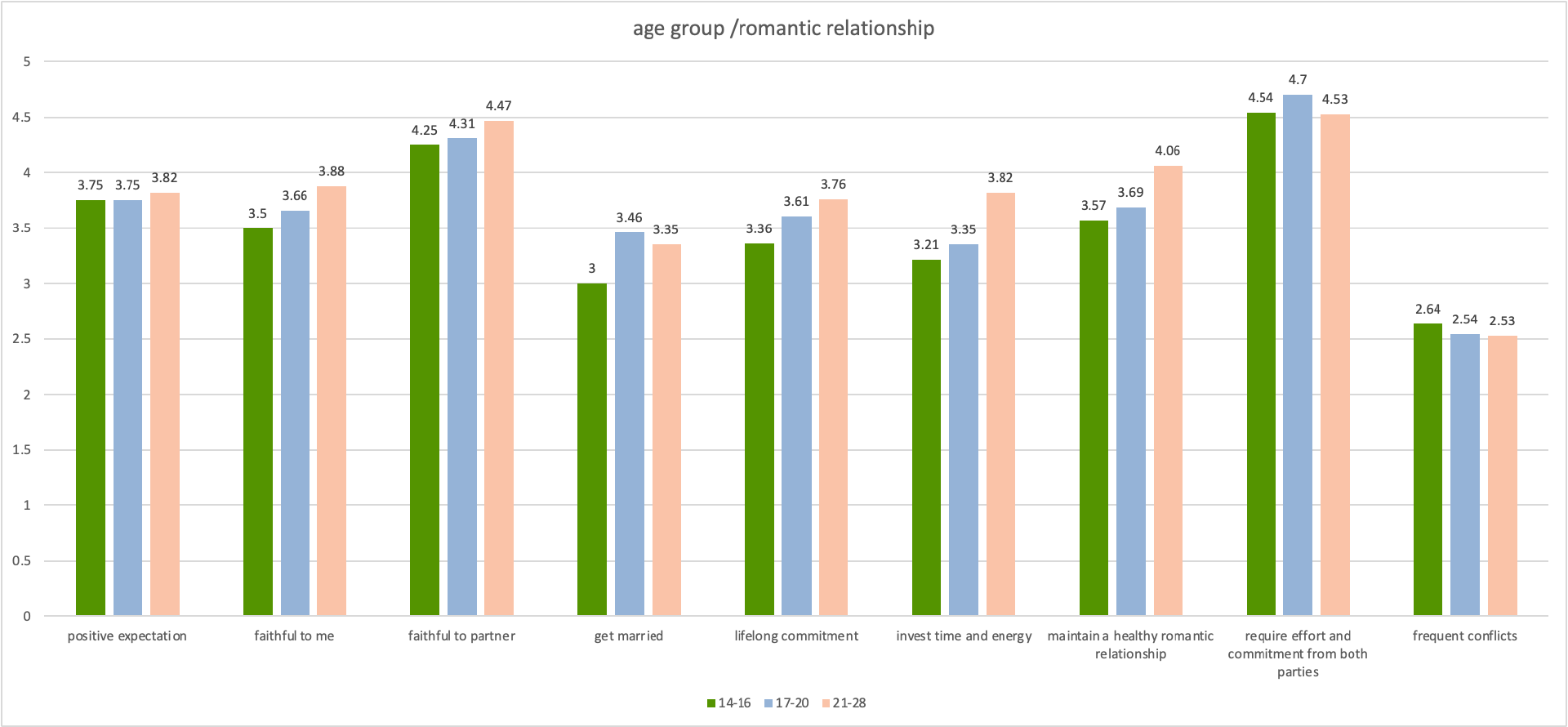

The result shows that as age increases, there is a generally more positive outlook on romantic relationships, with the exceptions of "willingness to marry", "beliefs about the necessity of effort and commitment from both parties", and "the expected frequency of conflicts". Across all age groups, the strongest consensus was observed in the belief that romantic relationships require effort and commitment from both parties, with mean scores of 4.54 for the 14-16 age group, 4.7 for the 17-20 age group, and 4.53 for the 21-28 age group. Moreover, all age groups have the lowest expectation for the occurrence of frequent conflicts, with mean scores of 2.64 for the 14-16 age group, 2.54 for the 17-20 age group, and 2.53 for the 21-28 age group.

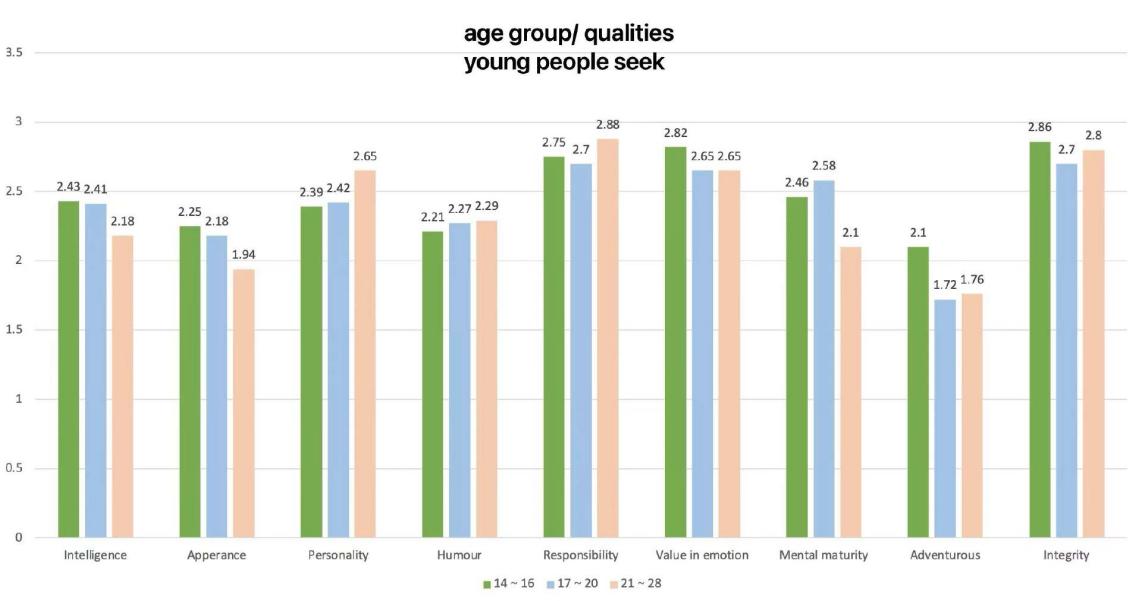

The result shows that all age groups value "responsibility" and "integrity" in their future partner more compared to the other seven items assessed. According to the bar chart, the 14-16 age group scored a mean of 2.86 on “integrity”, which is the most concerned quality they seek in their future partners. The 17-20 age group scored 2.7 for both "integrity" and "responsibility". We observed that the 17-20 age group, compared to the 14-16 and 21-28 age groups, did not exhibit particularly high expectations for any specific qualities in a future partner. In contrast, the 21-28 age group placed a significantly higher emphasis on the “responsibility” of a future partner, with an average score of 2.88. Furthermore, all age groups reported the lowest scores for "adventurous", with the mean score of 2.1,1.72, and 1.76 respectively.

4.2.2. Gender differences

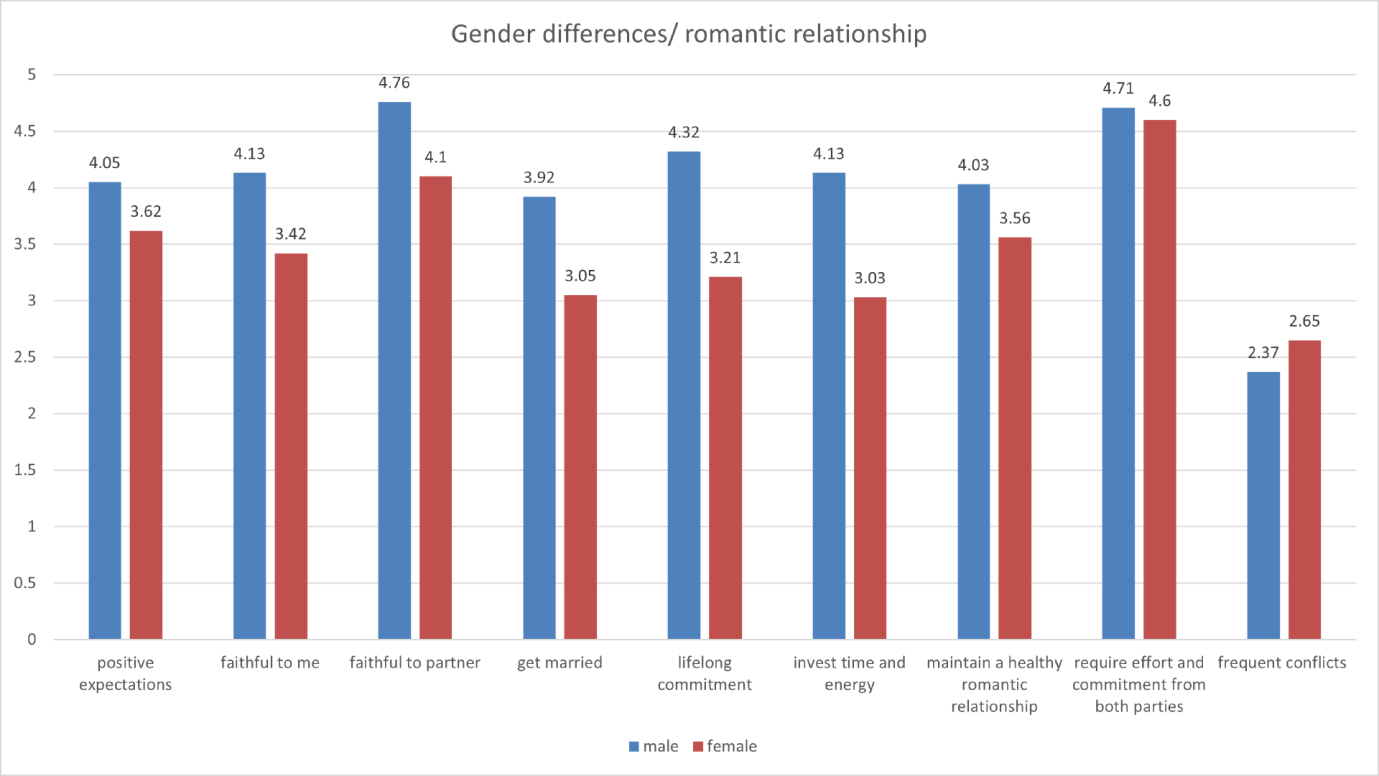

Within-sex comparison:

These results suggest that males hold more positive views on "faithful to partner" and "the requirement of effort and commitment from both parties in a romantic relationship" compared to the other seven items assessed. According to the graph, males reported significant high scores on their perspectives towards "faithful to partner" and "the requirement of effort and commitment from both parties in a romantic relationship" with mean scores of 4.76 and 4.71 respectively. In other aspects, such as "positive expectations", "faithful to me", "willingness to get married", "willingness to make lifelong commitment", "willingness to invest time and energy" and "confidence in maintaining a healthy romantic relationship", they received similar scores from male, which were all ranged from 3.92 to 4.32. For "the prediction of frequency of conflicts between partners", it received the lowest score (mean=2.37).

Females reported significant high scores on the same two aspects as males, with the mean score of 4.1 and 4.6 respectively. Aspects including "positive expectations", "faithful to me" and "confidence in maintaining a healthy romantic relationship" received moderate scores with a mean of 3.62, 3.42, and 3.56 respectively. Females reported lower scores on their perspectives towards "getting married", "making lifelong commitment" and "investing time and energy" in a romantic relationship, with the mean score of 3.05, 3.21 and 3.03 respectively. For "the prediction of frequency of conflicts between partners", it received the lowest score (mean=2.65), which was comparable to the score observed in males.

Between-sex comparison:

Overall, males have significantly more positive perspectives on romantic relationships, except for their beliefs in the likelihood of frequent conflicts with their future partner.

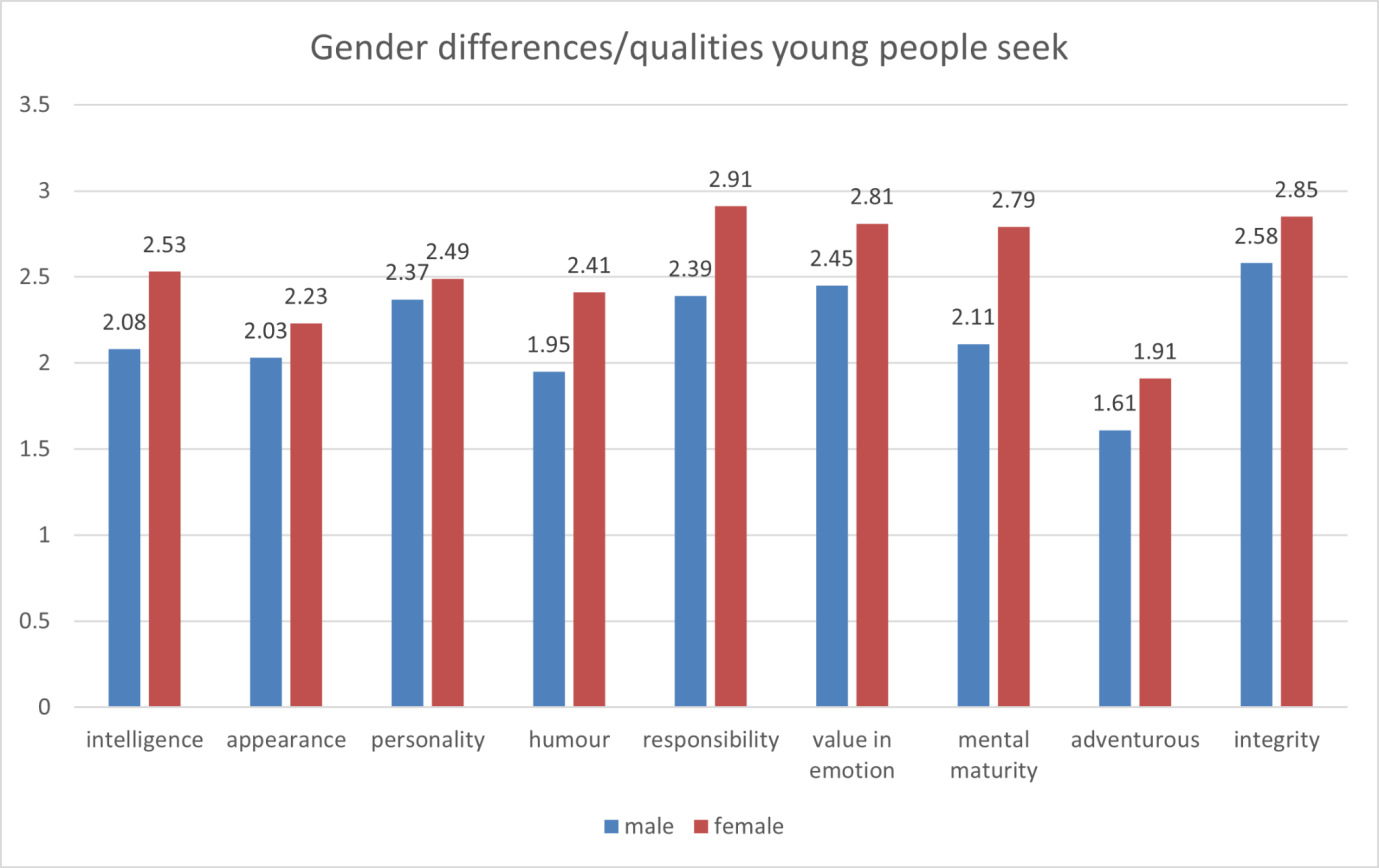

Within-sex comparison:

The results show that males value “integrity” more in their future partners compared to the other eight items assessed. According to the bar chart, males scored a mean of 2.58 on “integrity”, which is the most concerned quality they seek in their future partners. Regarding other qualities, such as “personality”, “responsibility” and “value in emotion”, males reported similar scores, which ranged from 2.37 to 2.45. Males reported the second lowest scores on qualities including “intelligence”, “appearance”, “humour” and “mental maturity”, with the means of 2.08, 2.03, 1.95 and 2.11 respectively. For the quality “adventurous”, male valued them least (mean=1.61).

Females reported significant high scores on four qualities, namely, “responsibility”, “value in emotion”, “mental maturity” and “integrity”, with the mean score of 2.91, 2.81,2.79 and 2.85 respectively. Qualities including "intelligence", "appearance" and "personality" and “humour” received moderate scores with a mean of 2.53, 2.23, 2.49 and 2.41 respectively. Females reported the lowest score on the quality “adventurous” as well, which was comparable to the score rated by males.

Between-sex comparison:

For all the nine qualities, females value them more compared to males, meaning that females have a higher expectation for their future partner.

4.2.3. Parental relationship

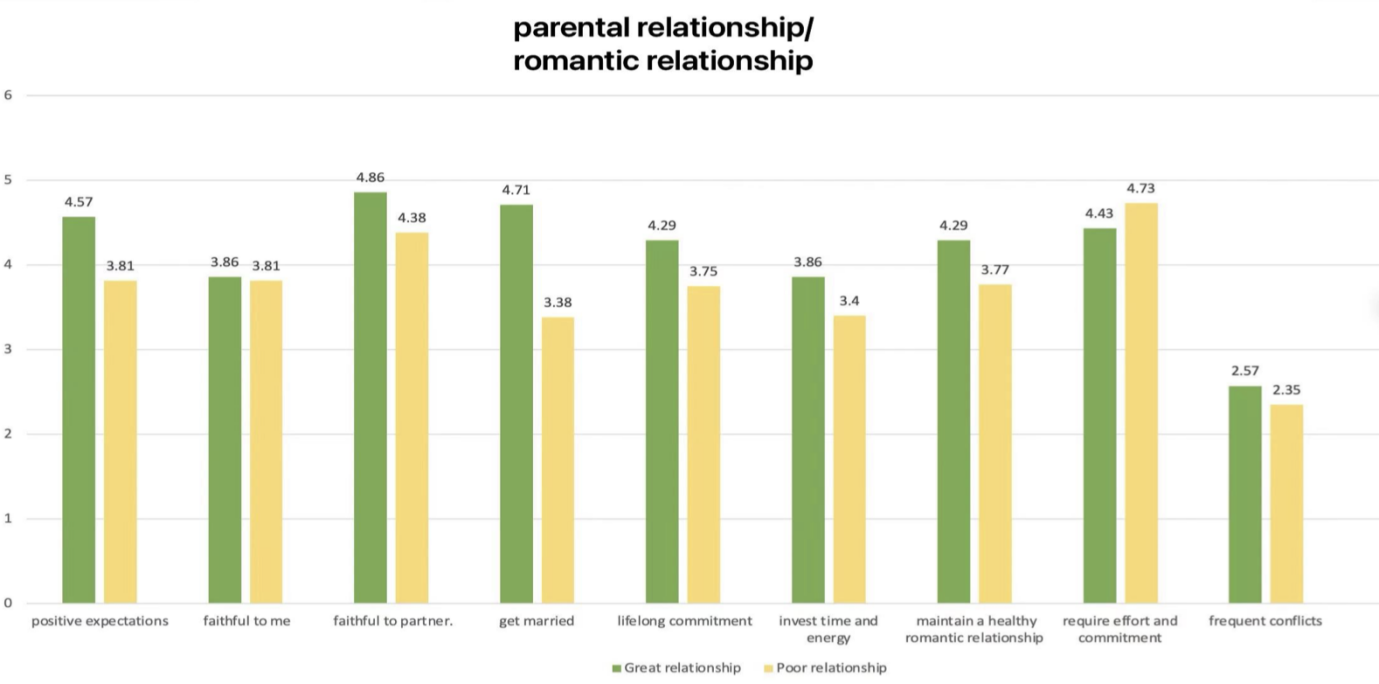

This graph illustrates the correlation between the quality of parental relationships and how young people perceive romantic relationships. It highlights that individuals whose parents have great relationships tend to view romantic partnerships with greater optimism and positivity across several dimensions. These dimensions include positive expectations, faithfulness, marriage prospects, lifelong commitment, the investment of time and energy, and the ability to maintain a healthy relationship. For instance, the graph shows that when it comes to "positive expectations," young people with parents in great relationships rated this aspect significantly higher, with an average score of 4.57, compared to 3.81 for those with parents in poor relationships. This pattern is consistent across other dimensions as well. For example, in the aspect of "faithfulness to partner," the ratings are 4.86 versus 3.86, and for "lifelong commitment," the ratings are 4.71 versus 3.75. Interestingly, while there is a general trend of higher ratings among those with parents in great relationships, the gap narrows in areas such as "effort and commitment," where the ratings are closer—4.29 versus 3.77. This suggests that regardless of parental relationship quality, the perceived need for effort and commitment in romantic relationships is recognized similarly by both groups. However, the ratings for "frequent conflicts" show a notable difference, with those from great parental relationships rating it much lower (2.57) compared to those from poor relationships (2.35), indicating a belief that conflicts are less frequent in their envisioned romantic relationships.

Overall, the graph reinforces the hypothesis that parental relationship quality significantly influences young people's outlook on romantic relationships, with a generally more positive perspective among those with parents in great relationships.

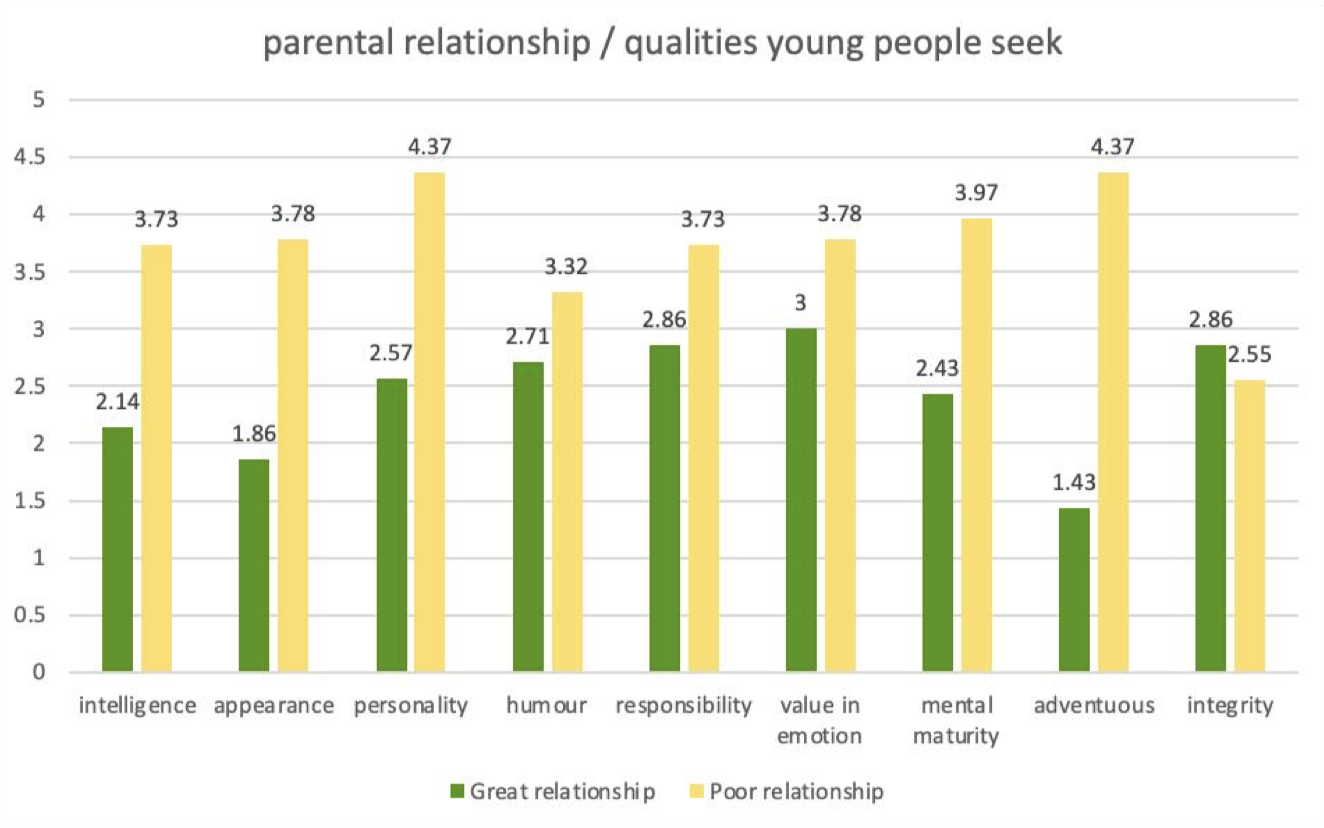

This graph delves into the specific qualities that young people seek in their future partners, contrasting those from great parental relationships with those from poor ones. It reveals that individuals with parents in poor relationships tend to have higher expectations for certain qualities, particularly in areas like adventurousness, appearance, and personality. This trend suggests that these individuals may be seeking qualities in their future partners that compensate for the deficiencies or challenges they observed in their parents' relationships. For instance, in the quality of "appearance," young people from poor parental relationships rate it much higher (3.78) compared to those from great relationships (1.86). Similarly, "adventurousness" is rated significantly higher by those from poor relationships (3.97) versus those from great relationships (1.43), indicating a stronger desire for a partner who brings excitement and novelty to the relationship. On the other hand, when it comes to "integrity," the data reveals an exception to the trend. Here, those from great parental relationships rate integrity slightly higher (2.86) compared to those from poor relationships (2.55). This suggests that despite other higher expectations, integrity remains a more stable and universally valued trait, with less variation between the two groups.

The most striking difference is seen in the expectation of "adventurousness," where the gap between the two groups is the largest. This significant disparity indicates that young people from poor parental relationships may prioritize excitement and adventure in their future partnerships as a means of avoiding the monotony or dissatisfaction they might have witnessed in their parents

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of results

The findings of this study strongly support the hypothesis that young people whose parents frequently express positive emotions towards each other tend to hold more positive expectations regarding romantic relationships. This outcome aligns with the Social Learning Theory [3], which suggests that children internalize behaviors and attitudes by observing their parents [10-12]. The results also align with Attachment Theory [4], which predicts that secure attachment, fostered in a warm and positive parental environment can lead to healthier relationship expectations in adulthood. By observing the consistent positive emotional expressions between parents, young adults may develop a more optimistic and secure expectations on their future romantic relationships, reflecting the importance of parental modeling in shaping interpersonal expectations [6].

This study also reveals how age, gender, and parental relationship quality interact to influence young people's romantic expectations. As people get older, they tend to see romantic relationships in a more positive light, yet with increased complexity and caution. This finding differs from earlier studies, such as Einav [7] associated increasing age with stronger marital intentions. Our research suggests that maturity typically enhances positive attitudes toward relationships and also introduces a greater sense of caution and pragmatism. This aligns with Steinberg et al. [10] who proposed that young people's views on long-term commitments are evolving. As young adults become more self-reliant and pragmatic, they may be moving away from traditional expectations of relationships. The differences in gender were also significant. Men tend to have higher expectations of fidelity and commitment but being more cautious about conflicts while women prioritized certain qualities in their partners, such as responsibility and emotional maturity. Traditional gender role theories usually associate men with a greater concern for freedom and risk-taking in relationships[11], but this finding partially contradicts them. The difference observed in men's emotional expectations may be a sign of evolving gender roles that challenge traditional expectations [5]

The quality of parental relationships has been validated as influential in this study. However, individuals who had less positive parental relationships showed heightened expectations for traits like adventurousness in partners. This trend is possibly due to compensating for the shortcomings they observed in their parents' relationships. This complex dynamic provides a new perspective on intergenerational influences, indicating that children might search for what they perceive to be missing from their parents' relationship with their future partners [1,9].

5.2. Implications

Investigating the influence of parental emotional expressions on young people's romantic expectations not only confirms current theories but also extends them, revealing the intricates in how parents’ behavior affect young adult’s development. It is crucial to have these insights in order to build more efficient interventions and educational programs that aim to foster healthy and fulfilling relationships for future generations [10]. Interventions that encourage healthy and positive interactions between parents can enhance both their relationships and their children's future romantic relationships. Since these interactions have a big influence on how the next generation views romantic relationships, family therapy and parental guidance programs should include techniques to improve good emotional exchanges within the family[6]. Based on the observed gender differences, it is suggested that relationship education be tailored to address these different perspectives. Challenging traditional gender norms and promoting a more balanced view of relationship dynamics through educational programs can help both men and women develop healthier and more realistic expectations which contribute to a more fulfilling and stable romantic relationship [5,11]

5.3. Limitations

Although this study provides valuable insights, it is important to acknowledge several limitations. The relatively small sample size, especially the low number of male participants, limited our finding’s generalizability. The self-reported data could lead to biases, as participants' responses could be influenced by social desirability or memory recall problems [10]. The sample's geographic location, primarily in urban areas such as Shanghai, Beijing, and Guangdong, further diminishes the variety of perspectives captured in this study. To improve the generalizability of the findings, future research should include a more geographically and culturally diverse sample [1]. In addition, the choice in questionnaire may not fully represent the complexity of participants' attitudes towards romantic relationships, indicating the need for more detailed and complete measurement tools [5].

6. Conclusion

This study has provided valuable insights into how parental emotional expressions impact young adults' romantic expectations, revealing the critical role that family dynamics play in shaping these outlooks. By combining Social Learning Theory and Attachment Theory, the research demonstrates how positive parental interactions result in healthier and more optimistic relationship expectations for their children. The study stresses the significance of considering age, gender, and parental relationship quality as important factors.

The findings emphasize the need for focused interventions and educational programs that support positive emotional exchanges in families, bearing in mind the long-term impact these interactions have on the next generation's approach to romantic relationships. Future research should examine how gender roles and societal expectations impact relationship development as society continues to evolve, and investigate how these dynamics can be explored across diverse cultural contexts. This research will enhance our understanding and guide better family-based interventions and educational efforts that focus on fostering healthier and more fulfilling relationships for future generations.

References

[1]. Kwan, Michael. “What Killed Marriage? China’s Divorce Rate Is up 75% in a Decade | CEIBS. ” Www. ceibs. edu, 2 Dec. 2021, www. ceibs. edu/new-papers-columns/20503.

[2]. McElwain, A. , McGill, J. , & Savasuk-Luxton, R. (2017). Youth relationship education: A meta-analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 82, 499–507. https://doi. org/10. 1016/j. childyouth. 2017. 09. 036

[3]. Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice Hall.

[4]. Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Books.

[5]. Jamison, T. B. , & Lo, H. Y. (2021). Exploring parents’ ongoing role in romantic development: Insights from young adults. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 38(1), 84–102. https://doi. org/10. 1177/0265407520958475

[6]. Chen, Z. , Fan, C. , & Zhang, H. (2013). The subjective experience of parental marital relationships and children's marital psychology. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(4), 507-512.

[7]. Einav, M. (2014). Perceptions About Parents’ Relationship and Parenting Quality, Attachment Styles, and Young Adults’ Intimate Expectations: A Cluster Analytic Approach. The Journal of Psychology, 148(4), 413–434. https://doi. org/10. 1080/00223980. 2013. 805116

[8]. Feldman, S. S. , Gowen, L. K. , & Fisher, L. (1998). Family relationships and gender as predictors of romantic intimacy in young adults: A longitudinal study. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 8(2), 263–286. https://doi. org/10. 1207/s15327795jra0802_5

[9]. Cui, M. , Fincham, F. D. , & Pasley, B. K. (2008). Young Adult Romantic Relationships: The Role of Parents’ Marital Problems and Relationship Efficacy. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(9), 1226–1235. https://doi. org/10. 1177/0146167208319693

[10]. Steinberg, S. J. , Davila, J. , & Fincham, F. (2006). Adolescent Marital Expectations and Romantic Experiences: Associations with Perceptions About Parental Conflict and Adolescent Attachment Security. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35(3), 333–348.

[11]. Mahl, D. (2001). Gender role theory and expectations in romantic relationships. Journal of Social Psychology, 141(2), 285-293.

[12]. Chlosta, S. , Patzelt, H. , Klein, S. B. , & Dormann, C. (2012). Parental role models and the decision to become self-employed: The moderating effect of personality. Small Business Economics, 38(1), 121–138. https://doi. org/10. 1007/s11187-010-9270-y

Cite this article

Cao,S.;Hua,R.;Lin,S.;Shi,Y.;Shao,Z. (2025). The Impact of Parental Interactions on Young People's Perspectives of Romantic Relationship. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,105,15-31.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Global Politics and Socio-Humanities

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Kwan, Michael. “What Killed Marriage? China’s Divorce Rate Is up 75% in a Decade | CEIBS. ” Www. ceibs. edu, 2 Dec. 2021, www. ceibs. edu/new-papers-columns/20503.

[2]. McElwain, A. , McGill, J. , & Savasuk-Luxton, R. (2017). Youth relationship education: A meta-analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 82, 499–507. https://doi. org/10. 1016/j. childyouth. 2017. 09. 036

[3]. Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice Hall.

[4]. Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Books.

[5]. Jamison, T. B. , & Lo, H. Y. (2021). Exploring parents’ ongoing role in romantic development: Insights from young adults. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 38(1), 84–102. https://doi. org/10. 1177/0265407520958475

[6]. Chen, Z. , Fan, C. , & Zhang, H. (2013). The subjective experience of parental marital relationships and children's marital psychology. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(4), 507-512.

[7]. Einav, M. (2014). Perceptions About Parents’ Relationship and Parenting Quality, Attachment Styles, and Young Adults’ Intimate Expectations: A Cluster Analytic Approach. The Journal of Psychology, 148(4), 413–434. https://doi. org/10. 1080/00223980. 2013. 805116

[8]. Feldman, S. S. , Gowen, L. K. , & Fisher, L. (1998). Family relationships and gender as predictors of romantic intimacy in young adults: A longitudinal study. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 8(2), 263–286. https://doi. org/10. 1207/s15327795jra0802_5

[9]. Cui, M. , Fincham, F. D. , & Pasley, B. K. (2008). Young Adult Romantic Relationships: The Role of Parents’ Marital Problems and Relationship Efficacy. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(9), 1226–1235. https://doi. org/10. 1177/0146167208319693

[10]. Steinberg, S. J. , Davila, J. , & Fincham, F. (2006). Adolescent Marital Expectations and Romantic Experiences: Associations with Perceptions About Parental Conflict and Adolescent Attachment Security. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35(3), 333–348.

[11]. Mahl, D. (2001). Gender role theory and expectations in romantic relationships. Journal of Social Psychology, 141(2), 285-293.

[12]. Chlosta, S. , Patzelt, H. , Klein, S. B. , & Dormann, C. (2012). Parental role models and the decision to become self-employed: The moderating effect of personality. Small Business Economics, 38(1), 121–138. https://doi. org/10. 1007/s11187-010-9270-y