1. Introduction

Millions of years ago, human ancestors lived in small groups. In such groups, they can create social bonds and cooperate with each other when facing environmental challenges. In nature, humans are social creatures that seek acceptance from others and form connections with each other. On the way of transforming to modern society, this principle never proved to be wrong.

In general, social exclusion is described as a state where a person is being marginalized or rejected from a group. Additionally, it is also a phenomenon that is in relation to inequalities[1]. Social exclusion is now seen as a global issue in which people face in their everyday life. Research finds that about 31.1 to 32.4 percent of the global population are at risk of social exclusion[2]. People can be excluded due to a variety of factors, such as socioeconomic status, race, religious affiliation and appearance. This situation of being marginalized can lead to a series of results, seriously affecting people’s lives and damaging mental and psychical health. On a psychological level, exclusion affects people’s mental performance by reducing intelligent thoughts and damaging self-regulation[3]. It also leads to response like anxiety, jealousy, loneliness, depression and low self-esteem[4].

People are at risk of experiencing exclusion in many contexts, such as schools, social gatherings and even when experiencing intimate relationship. When placing social exclusion in a workplace setting, it is conceptualized as the experience of being ignored, avoided, and/or rejected by at least one other organizational member. Workplace exclusion impacts employee’s overall well-being and related attitudes. According to a survey commissioned by The Task Force, 7% of the 5252 respondents reported to have suffered from workplace bullying in the last six months and 35% of the cases are related with exclusion. Based on researches, female tend to be more sensitive to negative emotion[5]. On the other hand, male tend to be more competitive than female in many settings, for example sports[6]. These gender-based differences can lead to different experience on workplace exclusion. While there are all kinds of works being done in this field, there is a limited amount of effort in researching the gender-based difference in the effect of exclusion while placing it in a workplace setting.

In this work, we aim to examine the different responses of men and women when facing social exclusion in a workplace setting. We measure how exclusion affects people’s work-related attitudes and compare it based on gender. Our hypotheses are both male and female’s work attitude become more positive after inclusion and more negative after exclusion, and male will be more affected by exclusion, showing a greater change in work attitude. By understanding the impact of exclusion, organizers or supervisors can be more successful when managing their team members in a company. Moreover, knowing the gender-based difference in how people respond to workplace exclusion also helps companies to develop better working plans for their employees. A more suitable management strategy leads to a cohesive working environment, benefiting the company as a whole.

2. Method

We will report all measures, manipulations, and exclusions. This study will be approved by and carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Institutional Review Board for human participants with written informed consent obtained from all participants.

Participants. The experiment will include 180 participants in total. Power analysis revealed thar with N=180, assuming alpha = 0.05, and with a one-way ANOVA test, we can an effect size of f = .25 (small to medium) with 80% statistical power. All of these participants will be randomly selective from a Chinese company that we choose to conduct our study in. They will all be Chinese adults, ranging from 25 to 45 years old. The sex ratio of the 180 participants needs to be balanced, meaning that there will be 90 males and 90 females.

Design and procedure. The experiment will be a between-subject design. First of all, all participants will be asked to complete a pre-test survey, self-assessing their work attitude (see Figure 3 in the Appendix). The survey will ask the participants to rate their work attitude on a scale from -5 to 5, with -5 indicating the most negative work attitude, 5 being the most positive work attitude. Moreover, the supervisors of the participants will also be asked to complete the same survey assessing the participants’ work attitude (see Figure 4 in the Appendix). After this, the participants will be divided into male and female groups, then further randomly assigned to ‘included’ or ‘excluded’ group. (see Figure 5 in the Appendix) The ‘included’ group (both male and female) with experience inclusion in which the participants will enter a regular office meeting. Each participant will be allowed to share opinions when they have one and be asked for their opinions at least twice. Participants in the ‘excluded’ group will also enter a regular office meeting; however, in this meeting, each participant will be not asked to share their opinion and will be ignored when they are trying to raise a concern or question. The post-test survey will happen 2 days after the meeting where all participants and their supervisors will be asked to assess their work attitude again.

Materials. Survey given to participants; survey given to supervisors.

Data Analytic Approach. We will calculate the average on the rating of work attitude of each participant and his/her supervisor on the per-test survey get the work attitude of that participate before experiencing exclusion or inclusion. Then, we will add up the averages for each group (female ‘excluded’ group, male ‘excluded’ group, female ‘included’ group and male ‘excluded’ group) then divided by 45 (the number of participants of each group) to get the average work attitude for each group before the intervention. For the work attitude on the post-test survey, we will do the same thing. We will calculate the average on the rating of work attitude of each participant and his/her supervisor on the post-test survey get the work attitude of that participate after experiencing exclusion or inclusion. Then, we will add up the averages for each group (female ‘excluded’ group, male ‘excluded’ group, female ‘included’ group and male ‘excluded’ group) then divided by 45 (the number of participants of each group) to get the average work attitude for each group after the intervention. Once we get the averages for each group, a one-way ANOVA test is used to analysis the data. The pre- and post-intervention averages of all groups will be compared to show the effect of inclusion and exclusion on work attitude. After this, we will compare the magnitude of the change in work attitude between female ‘excluded’ group and male ‘excluded’ group, and between male ‘included’ group and female ‘included’ group.

3. Results

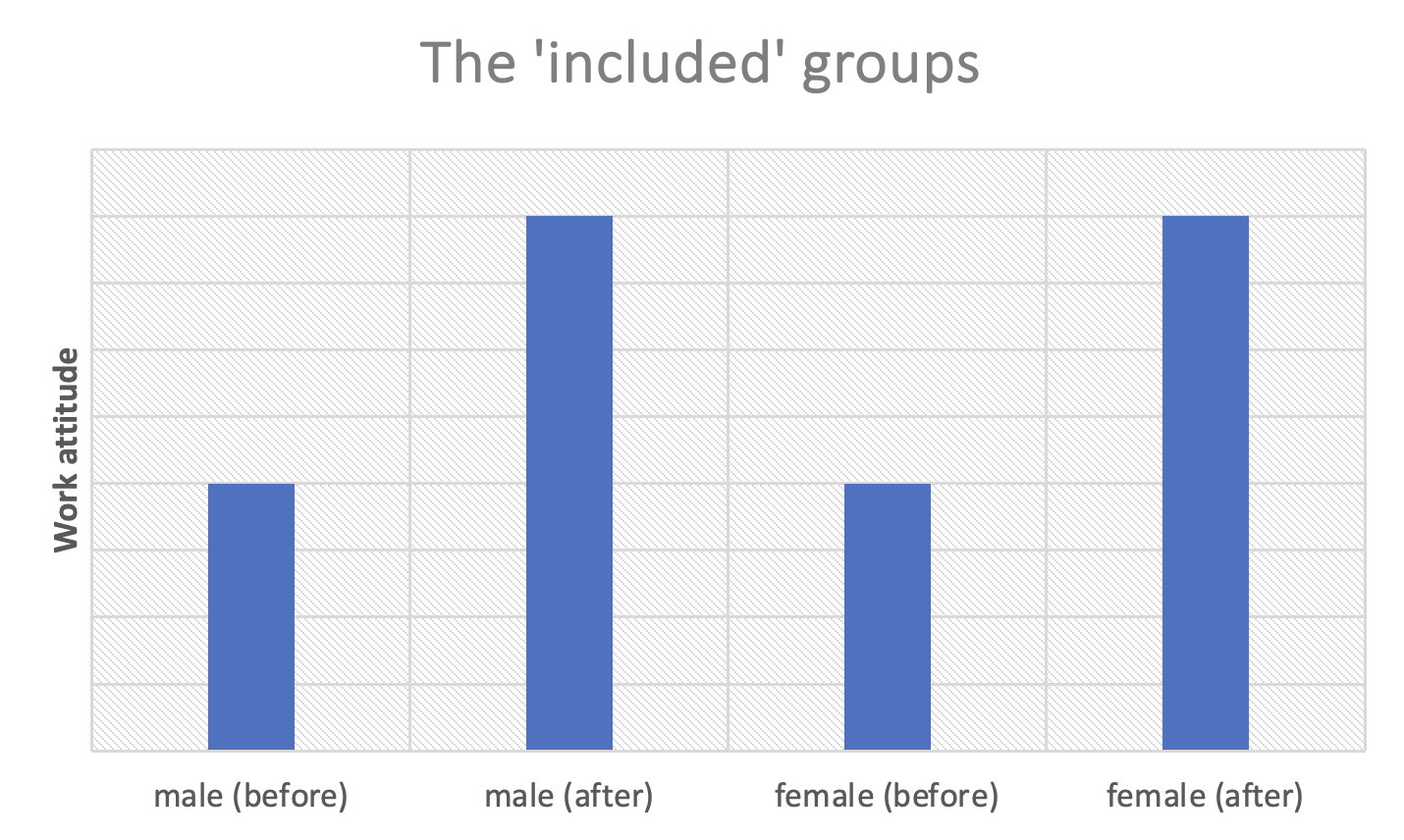

Aim 1. We predict that both male and female’s work attitude will become more positive after inclusion and will be affected to equal extent, showing similar increase in work attitude. The effect size is f = .25. See Figure 1.

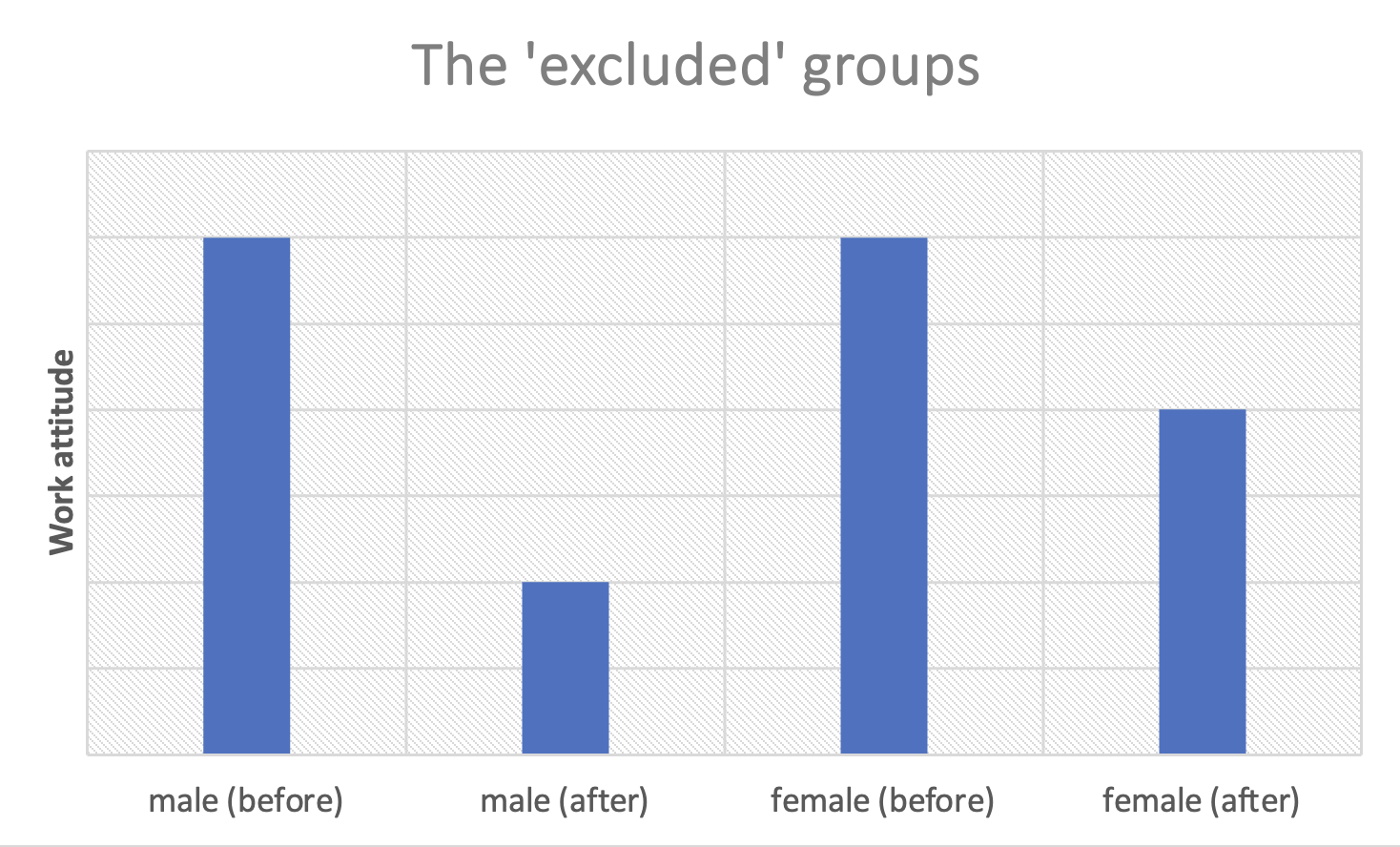

Aim 2. We predict that both male and female’s work attitude will become more negative after exclusion and male will be more affected than female, meaning that male’s work attitude will decrease more comparing to female. The effect size is f = .25. See Figure 2.

4. General discussion

This research aims to examine the effect of exclusion and inclusion on male and female work-related attitudes in workplace settings. The study also compares how males and females are affected differently by exclusion and inclusion. By knowing the effect, individuals can better understand how social connection can affect people, learn how to handle relationships, and how to cope with possible exclusion in life. Moreover, placing the experiment in a workplace setting and measuring the change in work attitude also helps companies to develop better arrangement policies.

Based on prediction, the findings of this study should suggest that after inclusion, both males and females will experience an increase in the rating of work attitude, indicating a more positive attitude. Study shows that inclusion is positively correlated with team role, innovator role performance[7] and assimilation outcomes, such as job competencies, coworker familiarity and involvement[8]. Furthermore, high inclusion and workplace dignity are also related with higher job performance[9]. Since there is a positive relationship between job attitude and job performance[10], work attitudes should become more positive when participants feel included. On the other hand, after exclusion, both males and females will experience a decrease in the rating of work attitude, indicating a more negative attitude. Research indicates a positive and direct relationship between exclusion and turnover intentions and turnover[11]. Also, there is a perceived relationship between exclusion and dissatisfaction of the organizational environment[12]. Since employees with good attitude are usually those who have high satisfaction[13], dissatisfaction caused by exclusion will lead to more negative work attitude. When comparing the scale of attitude change between males and females, we predict that the results reveal that both males and females are affected equally by inclusion; however, males are more affected by exclusion. This means that when males are being excluded, they experience a more drastic decrease in the rating of work attitude. This can be caused by the traditional gender role of men. Men are expected to be the person to earn money and support the family. They defined themselves more on their job performance comparing to female. Thus, when experiencing exclusion, this expectation made them be affected more seriously, causing greater decrease in work attitude. However, alternative interpretation does exist. It is possible that female is more affected by exclusion comparing to male, showing a greater decrease in the rating of work attitude. This can be explained by the tendency of women to be more vulnerable to anxiety. The number of women who have anxiety disorders is twice the number of men who have such disorders[14]. Additionally, female is also found to be more affected by stressful conditions comparing to male. Since situations where exclusion occur usually make the person being excluded feel left out which can then led to stress and create emotions related with anxiety, female might be more affected by exclusion than male since they are more sensitive to these type of negative emotion and condition.

The result of this study can be useful at both individual and organizational levels. On an individual level, it helps people, especially people who stay in the workplace, to deal with exclusion. People can understand the effect of exclusion and adjust themselves to reach a balance between the internal world and the outside environment. On an organizational level, exclusion is related to low satisfaction and confidence in the organization. Thus, based on the result, companies can modify and refine their arrangement strategy, reducing possible exclusion in the workplace, and creating a more cohesive environment for their employees.

The result of the experiment does address the effect of exclusion on males and females; however, there are still some limitations. First, when collecting information on participants' work attitudes, we use a partial self-report measurement to collect data. Since it is difficult to judge oneself from a purely objective, participants’ rating of their work attitude might be biased. Additionally, some participants might be afraid a low rating on work attitude will dissatisfy their supervisors, so they intentionally rate their work attitude higher than they truly think. Second, exclusion is generally seen as an undesirable situation to be in. When people experience exclusion, they might want to hide it from others so that they try to behave normally and look like they have not been affected at all. This might lead to a higher rating on work attitude across ‘excluded’ groups. Considering that the whole experiment is conducted in a workplace setting, the result might not be accurate when applied to exclusion outside of the working environment. Additionally, the participants are all selected in a single company. This also affects the generalizability of the result. Overall, it is believed that the result can be generalized to employees who work in a regular company.

This study primarily focuses how gender impact the effect of exclusion on work attitude. However, there are still a lot of other related researches can be done, for example, how workplace affect factors like turnover rate and job satisfaction. Moreover, individual differences are not examined in this study, so future study can focus on how personality interacts with workplace exclusion and influence job performance. All these help organizations to understand their employee’s’ decision and the intention behind it. Companies are also able to increase their performance based on the conclusion being reached. In the future, through continuous research, we hope to dive deeper and reach more reliable conclusion on the effect of exclusion in workplace, provide companies which the information that can be used to design better management policy which benefit both the organization itself and its employees.

5. Conclusion

This paper studies the effect of exclusion and inclusion on work attitude and how the scale of influence varies based on gender. Based on modeling workplace situation and exclusion stimuli, we reached several conclusions. First, when face inclusion, the work attitude for both males and females increases. Second, the effect of inclusion does not fluctuate based on gender, meaning that the work attitude for males and females increase relatively the amount after inclusion. Possible explanation for the increase in work attitude after inclusion is that inclusion correlates positively with team role performance[7] and job performance[10], therefore lead to better work attitude. Third, when counter exclusion, both males and females experience a decrease in work attitude. Explanation for this is that exclusion is shown to correlate with turnover[11] and dissatisfaction towards organization[12]; this can lead to lower work attitude. Fourth, even though after exclusion, both males and females decrease the work attitude, this decrease varies in scale in which males experience a more drastic decrease comparing to women. This can be explained by the gender role in which men are the money earner and define themselves based on their job performance. Thus, when being excluded, they are affected more dramatically. The conclusion of this study shows a better understanding on the effect on exclusion, especially in workplace setting. It can be applied in personal situation when individual faces exclusion and also in organizations to increase the overall performance of their members. By avoiding exclusion situation, companies can increase work attitude of their employees, leading to higher productivity and better working atmosphere. Concerning some limitation in this study, including self-reported data and failure to account for individual differences, only through continuous research in this area, a more reliable and generalizable understanding can be reached.

References

[1]. Cedeño, D. (2023). Social Exclusion and Inclusion: A Social Work Perspective. Families in Society, 104(3), 332-343. https: //doi.org/10.1177/10443894221147576

[2]. Cuesta, J., López-Noval, B., & Niño-Zarazúa, M. (2024). Social exclusion concepts, measurement, and a global estimate. Plos one, 19(2), e0298085.

[3]. Baumeister, R. F., Brewer, L. E., Tice, D. M., & Twenge, J. M. (2007). Thwarting the need to belong: Understanding the interpersonal and inner effects of social exclusion. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 1(1), 506-520.

[4]. Leary, M. R. (1990). Responses to social exclusion: Social anxiety, jealousy, loneliness, depression, and low self-esteem. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 9(2), 221-229.

[5]. Li, H., Yuan, J., & Lin, C. (2008). The neural mechanism underlying the female advantage in identifying negative emotions: an event-related potential study. Neuroimage, 40(4), 1921-1929.

[6]. Deaner, R. O. (2006). More males run fast: A stable sex difference in competitiveness in US distance runners. Evolution and Human Behavior, 27(1), 63-84.

[7]. Chen, C., & Tang, N. (2018). Does perceived inclusion matter in the workplace?. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 33(1), 43-57.

[8]. Miller, M. J., & Manata, B. (2023). The effects of workplace inclusion on employee assimilation outcomes. International Journal of Business Communication, 60(3), 777-801.

[9]. Ahmed, A., Liang, D., Anjum, M. A., & Durrani, D. K. (2022). Stronger together: Examining the interaction effects of workplace dignity and workplace inclusion on employees’ job performance. Frontiers in psychology, 13, 891189.

[10]. Rahiman, M. H. U., & Kodikal, R. (2017). Impact of employee work related attitudes on job performance. British Journal of Economics, Finance and Management Sciences, 13(2), 93-105.

[11]. Renn, R., Allen, D., & Huning, T. (2013). The relationship of social exclusion at work with self-defeating behavior and turnover. The Journal of social psychology, 153(2), 229-249.

[12]. Erdil, O., & Adıgüzel, Z. (2019). Impact of Organizational Justice on Psychological Contract Violations, Organizational Exclusion & Job Satisfaction. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences.

[13]. Ahmad, H., Ahmad, K., & Shah, I. A. (2010). Relationship between job satisfaction, job performance attitude towards work and organizational commitment. European journal of social sciences, 18(2), 257-267.

[14]. Donner, N. C., & Lowry, C. A. (2013). Sex differences in anxiety and emotional behavior. Pflügers Archiv-European Journal of Physiology, 465, 601-626.

Cite this article

Deng,Y. (2025). Workplace Exclusion and Gender: The Effect of Exclusion and Inclusion in Workplace Setting on Male and Female’s Work Attitude. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,105,75-81.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Global Politics and Socio-Humanities

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Cedeño, D. (2023). Social Exclusion and Inclusion: A Social Work Perspective. Families in Society, 104(3), 332-343. https: //doi.org/10.1177/10443894221147576

[2]. Cuesta, J., López-Noval, B., & Niño-Zarazúa, M. (2024). Social exclusion concepts, measurement, and a global estimate. Plos one, 19(2), e0298085.

[3]. Baumeister, R. F., Brewer, L. E., Tice, D. M., & Twenge, J. M. (2007). Thwarting the need to belong: Understanding the interpersonal and inner effects of social exclusion. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 1(1), 506-520.

[4]. Leary, M. R. (1990). Responses to social exclusion: Social anxiety, jealousy, loneliness, depression, and low self-esteem. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 9(2), 221-229.

[5]. Li, H., Yuan, J., & Lin, C. (2008). The neural mechanism underlying the female advantage in identifying negative emotions: an event-related potential study. Neuroimage, 40(4), 1921-1929.

[6]. Deaner, R. O. (2006). More males run fast: A stable sex difference in competitiveness in US distance runners. Evolution and Human Behavior, 27(1), 63-84.

[7]. Chen, C., & Tang, N. (2018). Does perceived inclusion matter in the workplace?. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 33(1), 43-57.

[8]. Miller, M. J., & Manata, B. (2023). The effects of workplace inclusion on employee assimilation outcomes. International Journal of Business Communication, 60(3), 777-801.

[9]. Ahmed, A., Liang, D., Anjum, M. A., & Durrani, D. K. (2022). Stronger together: Examining the interaction effects of workplace dignity and workplace inclusion on employees’ job performance. Frontiers in psychology, 13, 891189.

[10]. Rahiman, M. H. U., & Kodikal, R. (2017). Impact of employee work related attitudes on job performance. British Journal of Economics, Finance and Management Sciences, 13(2), 93-105.

[11]. Renn, R., Allen, D., & Huning, T. (2013). The relationship of social exclusion at work with self-defeating behavior and turnover. The Journal of social psychology, 153(2), 229-249.

[12]. Erdil, O., & Adıgüzel, Z. (2019). Impact of Organizational Justice on Psychological Contract Violations, Organizational Exclusion & Job Satisfaction. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences.

[13]. Ahmad, H., Ahmad, K., & Shah, I. A. (2010). Relationship between job satisfaction, job performance attitude towards work and organizational commitment. European journal of social sciences, 18(2), 257-267.

[14]. Donner, N. C., & Lowry, C. A. (2013). Sex differences in anxiety and emotional behavior. Pflügers Archiv-European Journal of Physiology, 465, 601-626.