1. Introduction

The Qing Dynasty had isolated itself in the 19th-century. China faced unprecedented external challenges, including foreign powers posing serious threats to China’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. While this period of time also marked the third major wave in Chinese translation history, when the scope of translation was expanded from geographical and historical texts to sciences, international politics, and Western cultures. Lin Zexu, recognized as one of the first modern Chinese officials to adopt a global perspective, organized the translation of English newspapers including Ao-men Hsin-wen-chih to “learn from foreigners to compete with them”.

Ao-men Hsin-wen-chih was an English-language newspaper published in Macau, covering international news, commercial updates, and political and military developments of Western powers. Lin Zexu recognized the strategic value of this information and systematically organized its translation. This initiative not only provided important information for Lin Zexu to formulate anti-opium policies and deal with diplomatic conflicts, but also marks China’s efforts in engaging with the outside world. It opened a window to the world for the isolated Qing society and laid the groundwork for subsequent reform movements such as the Westernization Movement and the Reform Movement of 1898.

Actor-Network Theory, as a sociological framework, emphasizes the interactive and mutually influential relationships among actors within networks. Using Actor-Network Theory, based on the collection The World Through Lin Zexu’s Eyes: Original Texts and Translations of Ao-men Hsin-wen-chih composed by Su Jing [1] this paper analyzes how human actors (Lin Zexu and his translation team) and non-human actors collaborated and interacted in the construction of a translation network, and how translation served as a process of negotiation and transformation.

2. Theory framework

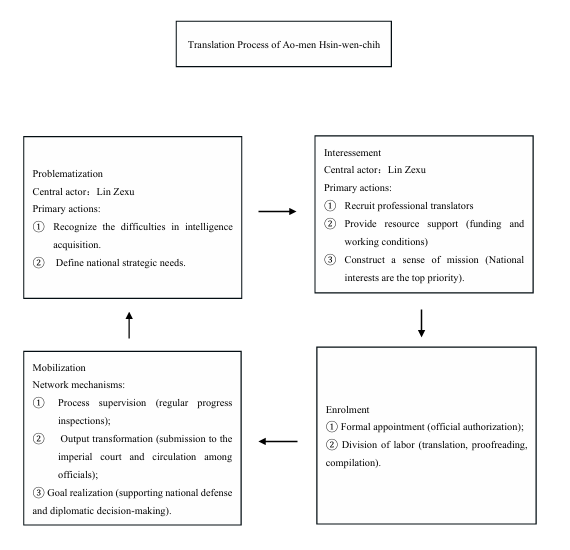

Actor-Network Theory (ANT), developed in the mid-1980s by French sociologists Michel Callon and Bruno Latour, is a sociological framework defining society as the outcome of the actions of various actors. According to ANT, actors engage in continuous activity to transform their relationships and constantly redefine and reconstruct their social identities. The theory revolves around three core concepts: actor, network, and translation. An “actor” is defined as any entity—human or non-human—that acts or is affected in a process [2]. Actors act spontaneously and respectively while shaped by the influence of one another. The dynamic traces of the actions interconnect and form a “network”, the second key concept. The factor that enables this network to function is “translation”—a process through which actors resolve conflicts of interest and establish associations through negotiation, persuasion and violence [3]. Through translation, actors not only reshape the roles and interests of others but also reconstruct their own identities. The translation process is marked by mutual construction and co-evolution among actors. Translation in ANT comprises four key phases: “problematization”, “interessement”, “enrolment”, and “mobilization”. These phases do not develop in a linear manner; rather, they are intertwined and evolve dynamically. Through translation, actors coordinate their interests and goals and adjust their roles within the network to achieve stability and expansion of the network.

ANT emphasizes that translation—particularly in the context of interlingual and intercultural communication—is a complex, dynamic process involving the interaction and negotiation among multiple actors. In addition to the source text, target text, author, and translator, a broader range of actors including organizers, policy-makers, editors, proofreaders, and target audience shape the translation process and its outcomes and should be considered. Canadian scholar Hélène Buzelin is one of the earliest scholars to integrate ANT into translation studies. In 2005, she began exploring the theoretical convergence between Latour’s actor-network approach and Bourdieu’s Theory of Practice, aiming to advance translation research and deepen process-and actor-oriented paradigms [4]. In recent years, scholars in China have increasingly recognized the application of ANT in translation studies. Huang Dexian discussed the existence of translation as networks and proposed the “follow the translator” method [5]. Other researchers, such as Zhou Biao and Zhang Jin [6], have conducted case studies to map actor-networks within specific translation activities, expanding the analytical scope from the source–target text and author-translator-reader relationships to include broader stakeholders such as sponsors, translation policies, and institutional frameworks. Wang Xiulu proposed an ANT research model based at bibliographical methods, supplemented by historical materials, with a focus on tracing actors involved in the translation process and constructing their networks [7]. Wang Feng and Qiao Chong further examined ANT’s methodological contributions, arguing that it complements the “causal model” of translation studies, enriching the research of translation process, and expands translation methods [8].

Current applications of ANT in Chinese translation studies remain largely theoretical or focused on literary translations—for example, Zhan Cheng and Zhang Han’s work on state translation programs [9], or Luo Wenyan’s ANT-based study of Arthur Waley’s English translation of Journey to the West [10]. Therefore, this paper has adopted ANT as the framework, so as to better analyze different parities in Ao-men Hsin-wen-chih.

3. The research material

Ao-men Hsin-wen-chih was compiled during Lin Zexu’s anti-opium campaign in Guangdong between July 1839 and November 1840, including 177 translated news articles from three English-language newspapers: The Canton Register, The Canton Press, and The Singapore Free Press. In addition to personal reference, Lin Zexu sent the translations to the Daoguang Emperor and relevant Qing officials.

These translated newspapers provided crucial intelligence for addressing the opium crisis and safeguarding national defense. Reports on the opium trade—such as the drug’ place of origin, transportation routes, and the commercial interests of British traders—enabled Lin to accurately track British opium merchants’ activities and develop more effective prohibition strategies. Similarly, coverage of Western military developments, including the deployment of British navy and advances in military equipment, proved vital to China’s coastal defense efforts on the eve of the First Opium War.

Through the act of translation, Lin Zexu effectively disrupted the information isolation of the Qing court, granting Chinese elites access to global knowledge, including Western politics, economics, military affairs, geography, commerce, and scientific advancements. This marked a significant expansion of worldview from the East Asian cultural sphere to a global perspective. Moreover, these translated texts planted the seeds of enlightenment thought in China. They prompted some Chinese intellectuals to reflect critically on the gap between China and the West and to reconsider the nation’s destiny. Building on Lin Zexu’s efforts, Wei Yuan compiled the Illustrated Records on the Maritime Nations, advocating the strategy of “learning from the West to counter the West” (shi yi chang ji yi zhi yi).

4. The construction of network in Ao-men Hsin-wen-chih

Translation is a purposeful activity [11]. As the central human actor, Lin Zexu initiated the translation project, aiming to investigate the foreign affairs. While the Qing government ostensibly supported the translation efforts as a means of understanding the West, its underlying intention was to reinforce the ideology and authority of the “Celestial Empire.” A tension thus emerged between Lin Zexu’s pursuit of factual accuracy, the Qing court’s ideological expectations, and the narratives presented in Western newspapers. The translation team was consequently required to negotiate among these conflicting interests in order to complete the translation task.

Lin Zexu’s translation practice offers a compelling illustration of the Actor-Network Theory’s emphasis on the complex interactions and dynamic translation processes among multiple actors. As the central actor in the translation network, Lin leveraged both his official authority and his political acuity to recognize the strategic value of Western press reports for national security. He mobilized a team of translators and gathered sources such as Ao-men Hsin-wen-chih, thereby constructing an actor-network centered on intelligence acquisition.

This network included Lin himself, four key translators (Aman, Alan, Yuan Dehui, Liang Jinde), and the Qing government as an institutional actor. The Qing court legitimized the project by providing financial and personnel support, but on the other hand limited the translation process through ideological constraints. In response, the translators deliberately softened Western criticisms toward China and edited sensitive content to align with the discursive framework of the Qing, revealing the court’s ideological presence within the network.

Importantly, Ao-men Hsin-wen-chih, as a non-human actor carrying Western political, military, and economic information, was both the foundation of the network and a subject of continuous transformation. Through negotiations and compromises among various actors, the source text was translated in ways that altered its original intent. It was not merely a carrier of information, but also embodied both objectivity and subjectivity.

5. Analysis of the translation process and methods

5.1. The translation process

Following ANT’s notion of opening the “black box,” researchers can reconstruct the decision-making and mediation processes behind the translations [7]. Lin Zexu’s project exemplifies dynamic and non-linear translation shaped by multiple actors’ interests.

5.2. Methods of translation

“Translation”, as Wang Xiulu argues, “can be regarded as a process of displacement, drift, invention, mediation, and connections between two domains.” [7] Researchers must therefore identify the actors involved, explain the interests motivating their actions, trace how these actions influenced one another, and analyze how through processes of alteration, creation, and mediation, the translation product was finished.

In the translation of Ao-men Hsin-wen-chih, various factors influenced translators' choices, leading them to adopt techniques such as addition and omission, as well as methods like transliteration and variation translation. These practices often resulted in distortions of the original English text, producing a translation tailored primarily for Lin Zexu, the Qing court, and the broader Chinese readers. Several examples illustrate this phenomenon:

5.2.1. Transliteration of proper nouns

Historical records indicate that while Lin Zexu’s translators had some proficiency in English, their language skills were limited, and their understanding of Western culture remained superficial. Aman could speak and write English but only at a basic level, while Yuan Dehui had studied English for less than two years in Malacca and had limited exposure to the outside world.

Due to limitations of language skills, translation techniques and cross-cultural experience, the translators tended to preserve the stylistic features of the English originals when rendering proper nouns. Instead of substituting with culturally equivalent Chinese terms, translators adopted transliteration. For instance, “English” was translated as “英咭利”(ying ji li) and “Christianity” as “克力士顿教”(ke li shi dun).

Moreover, unlike modern standardized practices for translating proper nouns, Translators then exhibited no consistency in transliteration conventions. The choice of Chinese characters for phonetic rendering was left largely to the individual translators’ discretion, resulting in multiple variants for the same term—for example, America appeared as “米利坚”,“咪唎坚” (mi li jian), “花旗” (the flag with stars and stripes, referring to the national flag of the US), and “育奈士(”yu nai shi).

Despite these technical shortcomings and the lack of standardization, the practice of transliteration must be evaluated within the 19th-century historical context. Transliteration was not merely a makeshift solution; it was an innovative attempt to transcend cognitive boundaries at an early stage of English-to-Chinese translation. This strategy preserved the heterogeneity of the source language to the greatest extent.

The use of characters such as “咪”(mi), “唎” (li) and “咭” (ji)—which were rarely used and carried no significant cultural connotations in Chinese—created a strong sense of strangeness. This deliberate estrangement reflects a foreignizing translation strategy that, within the closed cultural environment of the late Qing Dynasty, served a cognitive and educational function. It forced readers to recognize the untranslatability of certain linguistic signs, thereby shifting the traditional Chinese assumption of “a unified language” (tianxia tongwen). Compared to the domesticating strategy, the transliterations more authentically captured the barriers between Chinese and Western knowledge systems at the time, and provided valuable raw materials for the future standardized translation of proper terms.

5.2.2. Political considerations in the translation of naval battle and religious themes

The translators of Ao-men Hsin-wen-chih frequently employed variation translation techniques, whereby the original text was adjusted, rewritten, or reinterpreted to align with the cultural context of the target language, the expectations of its readership, or specific political purposes. A notable pattern emerges: the translators often softened or neutralized language from foreign newspapers that portrayed China in a negative tone.

For instance, in Article 10 (from The Friend of India), the phrase “here is a golden opportunity for giving China a lesson” would, if translated literally, read “这是给中国一个教训的好机会.” However, the translator rendered it as “是最好与中国理论的一个机会” (“the best opportunity to reason with China”), significantly mitigating the original tone of hostility and aggression. Similarly, the sentence “The Chinese, like all bullies, are cowards,” which reflects prejudices and stereotypes against China, was not translated literally as “中国人,就像所有的霸凌者一样,是懦夫.” Instead, it was transformed into “中国之兵皆似雄壮” (“Chinese soldiers all appear brave and strong”), demonstrating a deliberate strategy of cultural adaptation and political consideration.

This translation approach sought to avoid provoking cultural conflicts and inflaming nationalistic sentiments. It also served the immediate goals of the anti-opium campaign and broader national interests. Within the actor-network surrounding the translation process, such strategies reveal a functionalist orientation: information was carefully selected and reconstructed in ways that protected national dignity and upheld the image of Qing as a powerful empire. While the measures maintained the illusion of China’s continued supremacy, it is unsuccessful in that policymakers were still unable to recognize the Qing Dynasty’s deteriorating international position.

In the domain of religious content, similar political strategies were employed. The translators frequently blurred distinctions between various Christian denominations and often abridged or altogether omitted religious material from the translation.

ST: If such has been the result of the often repeated and indefatigable labours of the Catholic missionaries, who at the eminent risk of their lives penetrate into the country, it cannot surely be a matter of surprise that the Protestants have hitherto had no success, where the obstacles are so great and where their attempts have been so very slight. These therefore have, in our humble judgment, been the causes of the Chinese remaining deaf to the gospel, and not the opium traffic.

TT:传加特力之人若再冒危险行入内地,就有性命之忧,并有许多大阻难。故克力士顿教(Christianity)至今不行,中国人不欲闻经典之故,非因鸦片贸易之故。

In Article 108, “Protestant” was mistranslated as “克力士顿教”(Christianity).

ST: Roman Catholic, Protestant, Independent Baptist, and Ana-Baptist-the whole servants of the Propaganda Fide, the amiable and industrious gentlemen of the U.S. missions-the servants of God from Britain-the liberal and clear headed members of the Society for the propagation of useful knowledge -the Morrisonian institution whose patronimical name is alone a test of moral intentions; —these forming a more numerous band than all the foreign Opium-dealers in China.

TT:即如由我等国中之法,克力斯顿教之人,乃系比我等本国贩卖鸦片之人更多,而在中国禁止克力斯顿教 之法律,亦与禁止鸦片之法差不多。

Likewise, in the same entry, the translator omitted the distinct translations of various Christian denominations listed in the English original, such as Catholicism, Protestantism, and Baptism, and instead referred to them as “Christianity”.

ST: The vast population and debasing superstitions of China, are calculated to affect the sympathies of the Christian mind. That land is, however, fenced round by restrictions, so that the disciples of the Saviour can hardly gain access to the mass of the population. Missionaries have laboured assiduously among the Chinese emigrants…with pious endeavours to diffuse the Gospel. They have, therefore, attempted on a small scale, to relieve the more common maladies of the heathen around them, and have availed themselves of the opportunity thus afforded, to inculcate moral and religious truth on the minds of their patients.

TT:中国之人民,平常尽皆恨恶我等,不与我等往来,况又有官府之严禁,致我等虽用尽法子,欲解除中国人恨恶我等之心,惟总不能得之在我等各样事业之中,只有医学乃系中国人颇肯信之。向来有公司之时,公司医生虽亦有医治中国之人,惟因他们不甚识中国人之言语、品性,况又不是专心,所以就医者少。然斯时以来,中国人亦颇信欧罗巴各国医道之妙手,即已稍肯就医。

In Entry No. 147, which reprinted content from missionary Walter Medhurst’s China: Its State and Prospects, the original text discussed both missionary work and medical practice, with greater emphasis on religious matters than on medicine. However, in the Chinese translation, all references to religion were completely removed, and only the sections related to medicine were translated.

The confusion and omission of religious terms were not solely the result of the translators’ limited theological knowledge, but rather the outcome of mutual influence and compromise among human and non-human actors during the process of translation. Prior to the Opium War, Chinese scholars had a highly blurred understanding of Christian branches, often referring to both Protestantism and Catholicism collectively as “the Religion of Jesus” (Yesu Jiao). Although most of Lin Zexu’s translators had received education in Christian or Catholic schools, within this broader context of ambiguity, they may not have been fully aware of the distinctions among different branches.

Since the Yongzheng reign, the Qing Dynasty’s prohibition policies against Christianity, including legal codes such as the Great Qing Legal Code and the tradition of literary inquisition functioned as non-human actors, exerting significant pressure on the translation network. Translators were thus compelled to omit content of western religions in order to avoid the political risk of “spreading heterodox teachings”.

Within this framework, translators added fabricated statements such as “the Chinese people thoroughly detest us”, mimicking the tone of “foreigners” to construct a narrative that aligned with the Qing discourse of “distinguishing between Chinese and foreigners” (yi xia zhi bian). In reality, this strategy served as a proactive measure to avoid ideological risks: it catered to the government’s preconceptions of foreigners while stripping Western medical knowledge of its colonial associations, transforming it into a tool for reinforcing the ideology of “Chinese essence and western utility” (zhong ti xi yong).

At the same time, Lin Zexu’s pragmatic goal of translating only what was necessary for resisting the invasion from the west led to the omission of religious content while Western medical knowledge was retained for its utility—an approach consistent with the late Qing policy of prioritizing practical knowledge in the reception of Western learning.

Article 38, which describes the Battle of Chungpee, provides another example of how political considerations led translators to distort the original text.

ST: It is difficult to understand what can have led the Chinese to the attack on these two English ships of war, except it be a total misconception or ignorance of their strength.

The translator chose to omit this content. The phrase “ignorance of their strength” implies that the Qing court had overestimated the strength of its own navy while underestimating the British military power. If such expressions had been translated, they might have been interpreted as disrespect for the Qing military power, thereby undermining the morale of the troops or shaking public faith in the government. In this case, the translator effectively acted as a “mediator” within the actor-network, balancing the original information, the reception by the intended readership, and political constraints. Through strategic omission, the translator concealed the actual disparity between Chinese and Western military capabilities.

ST: It is difficult to foresee how this action may affect the disposition of the Chinese towards and arrangement with the English; we almost believe that they will become more tractable.

TT:现在已有此等情节,再难望中国好待我也。

“More tractable” means “easier to control”, yet the translator completely reversed the meaning of the original sentence. The British contempt for the Qing military strength conveyed in the original text was transformed in the translation into an expression of awe and respect for Qing military power, thereby aligning with the Qing court’s ideological narrative of the “invincibility of the Celestial Empire’s might”.

ST: Capt. Smith sent a despatch to the Commissioner at Chuenpee the purport of which was a demand that the Commissioner should withdraw his often repeated threats of burning and destroying the English merchant fleet now at Hongkong…This chop, having been delivered, the Chinese requested the ships of war to remove some way farther away from the Bogue, and Capt. Smith complied with their wish and dropped down about three miles, waiting for the reply.

TT:吐密(Smith)一到穿鼻,即递禀帖,求钦差不要烧毁在尖沙嘴湾泊之船只。递禀以后,退出约有三里,听候批示。

The wording in the English original—such as “sent a despatch”, “demand,” and “waiting for reply”—reflects a tone of equal diplomatic negotiation. However, the translated terms “递禀帖” (submit a petition), “求钦差” (beg the imperial commissioner), and “听候批示” (await an imperial decree) reveal a pronounced hierarchical distinction between “foreigners” and the “Celestial Empire”, forcibly incorporating what was originally an interaction between equals into the framework of the tributary discourse system.

The translations above reveal the essential nature of translation as a tool of political manipulation in the late Qing context. This strategy of translation was the result of the combined influence of multiple actors within the translation network, including censorship mechanisms and the ideology of “distinguishing between Chinese and foreigners”. Collectively, these cases demonstrate that the fundamental nature of late Qing translation was the distortion of meaning under centralized power, with its primary function not to convey real information, but to construct an illusion that served the needs of the ruling regime.

6. Conclusion

Under the framework of Actor-Network Theory, this paper has analyzed the translation strategies of Ao-men Hsin-wen-chih. While the translation marked a progressive step toward actively exploring outside world and advancing translation techniques, it also displayed significant limitations. Ideological constraints led to the omission or distortion of sensitive topics such as religions and military inferiority, limiting the Chinese audience’s reception of global realities.

ANT reveals translation not as mere linguistic activity, but as an active social practice shaped by a network of actors with competing interests, and thus enabling scholars to follow the translator, understand translation as a complex negotiation of interests and analyze the historical significance of translation practices.

References

[1]. Su Jing. “The World Through Lin Zexu’s Eyes: Original Texts and Translations of ‘Ao-men Hsin-wen-chih’” [M]. Guilin: Guangxi Normal University Press, 2017: 3-488.

[2]. Latour, Bruno. On Actor-Network Theory: A Few Clarifications [J]. Soziale Welt, vol. 47, no. 4, 1996, pp. 369–81.

[3]. Callon, M. & B. Latour. “Unscrewing the big Leviathan: How actors macrostructure reality and how sociologists help them to do so” [A]. In K. Knorr-Cetina & A. Cicourel (eds). Advances in Social Theory and Methodology: Toward an Integration of Micro- and Macro Sociologies [C]. Boston: Routledge, 1981.

[4]. Buzelin, H. “Unexpected allies: How Latour’s network theory could complement Bourdieusian analysis in translation studies” [J]. The Translator, 2005(2):193-218

[5]. Huang Dexian. “Translation: Existing in the Network” [J]. Shanghai Journal of Translators, 2006, (04): 6-11.

[6]. Zhou Biao, Zhang Jin. “Actor Network Theory and Southwest Minority tourism Translation” [J]. Guizhou Ethnic Studies, 2013, 34 (03): 67-70.

[7]. Wang Xiulu. “Actor network translation studies” [J].Shanghai Journal of Translators, 2019, (02): 14-20.

[8]. Wang Feng, Qiao Chong. “Methodological Implications of Actor-Network Theory for Translation Studies” [J]. Foreign Languages in China, 2023, 20(05): 88-95.

[9]. Zhan Cheng, Zhang Han. “An Analysis of State Translation Program from the Perspective of Actor-Network Theory” [J].Foreign Languages in China,2023,20(05):96-102.

[10]. Luo Wenyan. “Applying Actor-Network Theory to the Description of Translation Production Process: A Case Study of Arthur Waley’s Translation of Journey to the West from Chinese to English” [J].Foreign Languages Research, 2020, 37 (02):84-90.

[11]. Christian Nord. “Translating as a purposeful activity” [M]. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press, 2001

Cite this article

Li,X. (2025). A Study on Lin Zexu’s Translation Practice from the Perspective of Actor-Network Theory. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,106,24-32.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICEIPI 2025 Symposium: AI Am Ready: Artificial Intelligence as Pedagogical Scaffold

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Su Jing. “The World Through Lin Zexu’s Eyes: Original Texts and Translations of ‘Ao-men Hsin-wen-chih’” [M]. Guilin: Guangxi Normal University Press, 2017: 3-488.

[2]. Latour, Bruno. On Actor-Network Theory: A Few Clarifications [J]. Soziale Welt, vol. 47, no. 4, 1996, pp. 369–81.

[3]. Callon, M. & B. Latour. “Unscrewing the big Leviathan: How actors macrostructure reality and how sociologists help them to do so” [A]. In K. Knorr-Cetina & A. Cicourel (eds). Advances in Social Theory and Methodology: Toward an Integration of Micro- and Macro Sociologies [C]. Boston: Routledge, 1981.

[4]. Buzelin, H. “Unexpected allies: How Latour’s network theory could complement Bourdieusian analysis in translation studies” [J]. The Translator, 2005(2):193-218

[5]. Huang Dexian. “Translation: Existing in the Network” [J]. Shanghai Journal of Translators, 2006, (04): 6-11.

[6]. Zhou Biao, Zhang Jin. “Actor Network Theory and Southwest Minority tourism Translation” [J]. Guizhou Ethnic Studies, 2013, 34 (03): 67-70.

[7]. Wang Xiulu. “Actor network translation studies” [J].Shanghai Journal of Translators, 2019, (02): 14-20.

[8]. Wang Feng, Qiao Chong. “Methodological Implications of Actor-Network Theory for Translation Studies” [J]. Foreign Languages in China, 2023, 20(05): 88-95.

[9]. Zhan Cheng, Zhang Han. “An Analysis of State Translation Program from the Perspective of Actor-Network Theory” [J].Foreign Languages in China,2023,20(05):96-102.

[10]. Luo Wenyan. “Applying Actor-Network Theory to the Description of Translation Production Process: A Case Study of Arthur Waley’s Translation of Journey to the West from Chinese to English” [J].Foreign Languages Research, 2020, 37 (02):84-90.

[11]. Christian Nord. “Translating as a purposeful activity” [M]. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press, 2001