1. Introduction

Loneliness refers to a person's subjective feeling about the defects in his social relations and lack of intimacy and meaningful attachment to another person [1,2]. Maslow's hierarchy of needs theory points out that feeling a sense of belonging and social connection is a basic need and tendency, and people strive to overcome loneliness [3]. Loneliness is associated with stress, depressive symptoms, job burnout, poor physical health, and low well-being [4]. Although teenagers and young people are going through a critical period of interpersonal relationship development, they are at particularly high risks of feeling lonely [5]. After 2012, the loneliness of young people in Britain, the United States and Canada increased dramatically. The COVID-19 pandemic and social isolation further led to a significant increase in loneliness among young adults [6]. Therefore, understanding the reasons for loneliness is very important to solve the problem of loneliness. Among various factors leading to increases of loneliness, one possible factor is feelings of the meaning of life. According to positive psychology, the meaning of life is one of the major components of well-being, which is “life meaning” or purpose. People can find meaning by establishing connections and patterns from life events, by deeply participating in communities, and by belonging to and serving things bigger than themselves [7].

The lack of “meaning” in social interactions, rather than number or frequency, is usually considered as the key determinant of loneliness and emptiness [8]. In addition, according to Frankl, "people who have 'why' to live can endure almost any ‘how’", fighting for meaning is the basis of human life [9]. Having a sense of purpose and meaning will make individuals believe that their behavior has a fixed position in the larger things, and feel the values [10].

The lack of meaning in life leads to a kind of loneliness, which is called existential loneliness. It refers to feelings of being out of touch with the world, lacking goals and wandering in life [11]. According to Schnell and Krampe, meaning crisis is very common among people suffering from high levels of COVID-19 stress and general mental pain, which indicates that persistent anxiety and depression might be based on struggles for existence [12]. In contrast, meaningful people reported that in the context of COVID-19, the general mental pain was low.

Cultural factors also play a role in shaping the loneliness of individuals. Although there is no difference in the overall report level of loneliness between adolescents and young adults, the characteristics of loneliness vary from country to country [13]. For example, young adults from independent cultures like the US were more likely to report their lives as meaningful, whereas young adults from collectivist cultures like Japan reported a greater search for meaning [14]. As a collectivistic country, China has a strong Confucian tradition, emphasizing interpersonal relationships, which is an important factor causing loneliness and pressure [15]. Confucian culture emphasizes the harmony between people, and refers to the balance of individual relationships. This makes people with poor social skills face more disharmony in their daily life [16].

Past research generally uses explicit ways of assessing loneliness, particularly questionnaires including the UCLA Loneliness Scale, single self-rating scale [17], and three-item Loneliness Scale. These questionnaires measure loneliness by asking questions related to the sense of companionship and neglect [18]. In addition to explicit measurement, researchers like Nausheen adopted a more implicit and indirect method of loneliness measurement. Instead of asking participants to self-report their feelings, he used a computerized tool based on reaction time [19]. Specifically, Nausheen adapted an Implicit Association Test, which assesses the relative strength of associations and psychosocial constructs by comparing the performance of two pairs of concepts—self and others, lonely and nonlonely.

In addition, implicit cognition and explicit cognition has long been theorized into different processes [20, 21]. Implicit cognition is composed of latent, unconscious negative schemas, while explicit cognition is more involved in long-term schemas. It is possible that an individual’s explicit attitudes are not congruent with activated implicit cognitions [22]. More importantly, implicit, and explicit cognition predict different outcomes. For example, in the field of social attitudes, it has been found that implicit attitudes can predict nonverbal behaviors, such as eye contact and body posture. However, a clear attitude indicates a more cautious result [23, 24]. Therefore, in order to better study the relationship between loneliness and meaning of life, this research will adopt implicit and explicit loneliness measurement methods. Generally speaking, the purpose of this research is to explore the relationship between the meaning of life and loneliness. A better understanding of the determinants of loneliness would be helpful to reduce the intervention and methods of loneliness in the future. For example, this might imply the possibility of logotherapy in reducing loneliness.

Based on the above review, we put forward the following hypotheses.

H1: Young adults would feel lonely at both implicit and explicit levels.

H2: Young adults would feel a lack of meaning in life.

H3: There would be no correlation between implicit and explicit loneliness.

H4: There would be a relationship between loneliness and the meaning of life among young adults.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

A total of 36 participants were selected from college students. Thirteen participants were male, and twenty-two were female. The mean age was 21.16 years, ranging from 19.26 to 25.96 years. Data were collected between Nov 20 and Dec 4, 2021. Participants were recruited online. Adult participants gave written informed consent before their participation.

2.2. Procedure

Data were collected online, including the UCLA loneliness scale, Meaning in Life Questionnaire [25], Implicit Association Test [26], and demographic survey. Participants took part in the study separately.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. UCLA Loneliness Scale

The revised 20-item UCLA Loneliness Scale developed by Russell developed an explicit way of measuring loneliness. Participants rate each item from 1 (never) to 4 (often). This measure was revised from the original UCLA Loneliness Scale to simplify the wording and reverse score of 10 of the 20 original items. Sample items include “My interests and ideas are not shared by those around me,” “I feel part of a group of friends'', and “There are people who really understand me.” Higher scores indicate a higher level of loneliness.

2.3.2. Implicit Association Test of Loneliness

This is an adapted version of implicit association test, which examines loneliness in an implicit way. Implicit association test is a computerized reaction-time test to measure implicit attitudes, stereotypes, and self-concept. IAT requires participants to divide projects into four categories: self and others, loneliness and not loneliness. There are seven blocks, including two practice blocks before the two critical blocks. Subconscious associations are assessed by comparing the performance of the pairs of concepts.

2.3.3. Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ)

The meaning of life was measured by the 10-item Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ) developed by Steger. MLQ measures the two dimensions of life meaning: the existence of meaning (the degree to which participants understand the meaning in their lives and feel that their lives are meaningful) and search for meaning (the degree to which participants try to find meaning in their lives). In this list of self-reports, participants rated each item from 1 (absolutely correct) to 7 (absolutely incorrect) with Likert scale. Sample items include “My life has a clear sense of purpose” and “I am looking for something that makes my life feel meaningful.” Higher scores indicate a higher level of meaning in life.

3. Results

3.1. Implicit Loneliness

To examine whether participants show an implicit loneliness, we conducted a one-sample t-test. Results found that implicit D scores were significantly different from zero (no bias), t (35) =4.09, p < .001, Cohen’s d=.31. This result suggests that participants show implicit loneliness associating words representing me with words representing loneliness.

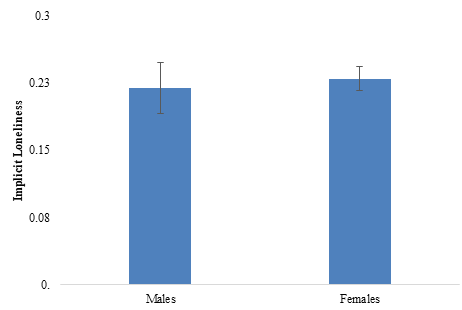

In order to further test whether the level of implicit loneliness between male and female participants is different, we conducted an independent sample t-test. Results found that there is no significant difference between the loneliness for males (M=.22, SD=.37) and females (M=.23, SD=.26) and t (33) =-.208, p=. 836.This result shows that there is no difference in levels of implicit loneliness between men and women.

3.2. UCLA Loneliness Scale

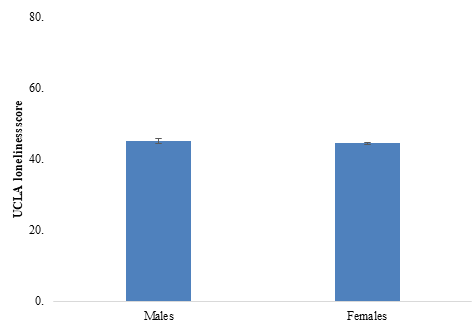

Similarly, in order to test whether men and women have different degrees of explicit loneliness, we conducted an independent sample t-test. Results found that there is no significant difference between the loneliness for males (M=45.14, SD=8.80) and females (M=44.43, SD=6.86); t (33) =.269, p=.789. This result shows that there is no difference in the degree of explicit loneliness between men and women. In order to further study whether their family income affects levels of explicit loneliness, we conducted a one-way ANOVA. There was no significant effect of family income on the levels of explicit loneliness, F (4, 31) =2.35, p=0.076. This result suggests that family household income does not affect adults’ levels of explicit loneliness.

3.3. Correlation Between Meaning in Life and Implicit/Explicit Loneliness

To examine whether there is a correlation between meaning in life and levels of explicit loneliness, we conducted a Pearson correlational analysis. Results showed that the meaning in life was significantly negatively correlated with loneliness, r (36) =-.360, p=.027. This result suggests that individuals who perceive more meaning in life tend to feel less lonely explicitly.

To examine whether there is a correlation between meaning in life and levels of implicit loneliness, we conducted a Pearson correlational analysis and found no significant correlation between the two. We also examined the correlations between demographics and other key variables. No correlations were found, all r < x, all p > y.

Figure 1: Implicit loneliness of male and female participants. Scores above zero represent implicit loneliness.

Figure 2: Explicit loneliness of male and female participants.

4. Discussion

It is a common subjective experience of lonely teenagers and young adults, and this experience is rapidly increasing with the emergence of COVID-19. In the current research, we have tested the relationship between the meaning of life and loneliness: whether the lack of meaning in life will lead to loneliness, and whether the perception of meaning of life will lead to the reduction of loneliness. Using data collected from Chinese international undergraduates in the United States, we find that young people of this age generally feel lonely, whether at the recessive or dominant levels. We also found that whether the sense of life is an important predictor of loneliness, especially the dominant loneliness. We discussed each of these result in detail below. First of all, we found that young people in China show recessive loneliness. In the implicit association test of loneliness, participants associate the words related to "I" with words that represent loneliness. This finding is consistent with our hypothesis that young adults would feel lonely at implicit levels.

Second, as for the explicit loneliness, due to the lack of threshold of UCLA Loneliness Scale, which indicates whether lonely or not lonely, we cannot find whether Chinese young adults are lonely or not lonely. Therefore, we failed to find out whether young adults feel lonely at explicit levels.

Third, we found no gender difference in implicit and explicit loneliness. In other words, males and females showed similar implicit and explicit loneliness. Previous research on loneliness also reported no statistically significant gender differences in loneliness as measured by the UCLA Loneliness Scale, but males typically have slightly higher scores of loneliness [27].

Finally, we studied the relationship between loneliness and meaning in life. We found that there was no correlation between meaning in life and implicit loneliness, but there was a negative correlation between meaning in life and explicit loneliness. This shown that, from a subjective point of view, people who see meaning of life and are looking for it usually think that they are not so lonely. However, the significance of life has nothing to do with whether people feel lonely implicitly.

The lack of correlation is consistent with previous work using implicit and explicit methods. As suggested by previous researchers, explicit self-report measures and implicit methods such as the IAT might measure distinct but related constructs. Mental process and mental experience are two different concepts [28]. Similarly, in this study, implicit loneliness and explicit loneliness are shown to be different processes. In the implicit association test, participants quickly matched structures and classified words, while in the explicit UCLA loneliness scale, participants reported their subjective feelings by answering questions related to loneliness. The methods of examination are different, and the results also turned out that these two types of loneliness differ in their relationship with the meaning of life, parental household income, and so on. This finding is consistent with the results of previous work by Nausheen, which also indicates that implicit loneliness was not significantly correlated with explicit loneliness.

There are several limitations in the current research. The first limitation is that the sample size is very limited, which might indicate limited practical applications. The second limitation is the lack of generalizability since all participants are Chinese international students in the United States. Some aspects of the research results may be culture specific. This special background shows the lack of universality applicable to all young people in this age group. Future research could incorporate some cross-national measures and examine loneliness across countries. In addition, more random samples can be used in future research to increase validity.

5. Conclusion

In a word, we investigated the implicit loneliness and explicit loneliness of young Chinese undergraduates in the United States, as well as their perceptions of the meaning of life. The result show that implicit loneliness is common among young people, and there is no gender difference in both implicit loneliness and explicit loneliness. Loneliness is negatively correlated with the meaning of life. The finding also has some practical implications. For example, the finding that loneliness is associated with a lack of meaning in life demonstrates that logotherapy and other life meaning-related interventions may be effective in reducing loneliness among adolescents.

References

[1]. Russell,D.,Peplau,L.A.,&Cutrona,C.E.(1980).The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale:Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,39(3),472–480.https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.472.

[2]. Weiss,R.S.(1974).The provisions of social relationships.In Z.Rubin(Ed.),Doing unto others(pp.17-26).Englewood Cliffs,NJ:Prentice-Hall.

[3]. Maslow,A.H.(1970).Motivation and Personality(2nd ed.).New York:Harper and Row.

[4]. Mushtaq,R.,Shoib,S.,Shah,T.,&Mushtaq,S.(2014).Relationship between loneliness,psychiatric disorders and physical health?A review on the psychological aspects of loneliness.Journal of clinical and diagnostic research:JCDR,8(9),WE01–WE4.https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2014/10077.4828

[5]. Goosby,B.J.,Bellatorre,A.,Walsemann,K.M.,&Cheadle,J.E.(2013).Adolescent Loneliness and Health in Early Adulthood.Sociological inquiry,83(4),10.1111/soin.12018.https://doi.org/10.1111/soin.12018

[6]. Twenge,J.M.,Haidt,J.,Blake,A.B.,McAllister,C.,Lemon,H.,&Le Roy,A.(2021).Worldwide increases in adolescent loneliness.Journal of adolescence,S0140-1971(21)00085-3.Advance online publication.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.06.006

[7]. Wilkinson,R.A.,&Chilton,G.(2013):Positive Art Therapy:Linking Positive Psychology to Art Therapy Theory,Practice,and Research,Art Therapy:Journal of the American Art Therapy Association,30:1,4-11

[8]. MaciàD,Cattaneo G,Solana J,Tormos JM,Pascual-Leone A and Bartrés-Faz D(2021).Meaning in Life:A Major Predictive Factor for Loneliness Comparable to Health Status and Social Connectedness.Front.Psychol.12:627547.doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.627547

[9]. Frankl,V.E.(1985).Man’s search for meaning(Revised and updated).New York,NY:Washington Square Press.

[10]. Krause N.(2004).Stressors arising in highly valued roles,meaning in life,and the physical health status of older adults.The journals of gerontology.Series B,Psychological sciences and social sciences,59(5),S287–S297.https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/59.5.s287

[11]. Sundström,M.,Edberg,A.K.,Rämgård,M.,&Blomqvist,K.(2018).Encountering existential loneliness among older people:perspectives of health care professionals.International journal of qualitative studies on health and well-being,13(1),1474673.https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2018.1474673

[12]. Schnell,T.,&Krampe,H.(2020).Meaning in Life and Self-Control Buffer Stress in Times of COVID-19:Moderating and Mediating Effects with Regard to Mental Distress.Frontiers in psychiatry,11,582352.https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.582352

[13]. Chen,X.,He,Y.,de Oliveira,A.M.,Coco,A.L.,Zappulla,C.,&Kasper,V.(2004).Loneliness and social adaptation in Brazilian,Canadian,Chinese,and Italian children:A multi-national comparative study.Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry,45,1373–1384.

[14]. Steger,M.F.,Kawabata,Y.,Shimai,S.,&Otake,K.(2008).The meaningful life in Japan and the United States:Levels and correlates of meaning in life.Journal of Research in Personality,42,660-678.

[15]. Zhao,J.,Song,F.,Chen,Q.,Li,M.,Wang,Y.,and Kong,F.(2018).Linking shyness to loneliness in Chinese adolescents:The mediating role of core self-evaluation and social support.Personality and Individual Differences,125,140-4.Doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.01.007

[16]. Lun,V.M.,&Bond,M.H.(2006).Achieving relationship harmony in groups and its consequence for group performance.Asian Journal of Social Psychology,9(3),195–202.

[17]. Victor,C.R.,&Yang,K.(2012).The prevalence of loneliness among adults:a case study of the United Kingdom.The Journal of psychology,146(1-2),85–104.https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2011.613875

[18]. Lee,C.M.,Cadigan,J.M.,&Rhew,I.C.(2020).Increases in Loneliness Among Young Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Association with Increases in Mental Health Problems.The Journal of adolescent health:official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine,67(5),714–717.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.009

[19]. Nausheen,B.,Gidron,Y.,Gregg,A.,Tissarchondou,H.S.,&Peveler,R.(2007).Loneliness,social support and cardiovascular reactivity to laboratory stress.Stress,10(1),37–44.https://doi.org/10.1080/10253890601135434.

[20]. Bargh,J.A.(1999).The cognitive monster:The case against the controllability of automatic stereotype effects.https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1999-02377-017

[21]. Greenwald,A.G.,&Banaji,M.R.(1995).Implicit social cognition:Attitudes,self-esteem,and stereotypes.Psychological Review,102(1),4–27.https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.102.1.4

[22]. Haeffel,G.J.,Abramson,L.Y.,Brazy,P.C.,Shah,J.Y.,Teachman,B.A.,&Nosek,B.A.(2007).Explicit and implicit cognition:a preliminary test of a dual-process theory of cognitive vulnerability to depression.Behaviour research and therapy,45(6),1155–1167.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2006.09.003

[23]. Kurdi,B.,Seitchik,A.E.,Axt,J.R.,Carroll,T.J.,Karapetyan,A.,Kaushik,N.,Tomezsko,D.,Greenwald,A.G.,&Banaji,M.R.(2019).Relationship between the Implicit Association Test and intergroup behavior:A meta-analysis.The American Psychologist,74(5),569–586.https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000364

[24]. Dovidio,J.F.,Kawakami,K.,&Beach,K.R.(2001).Implicit and explicit attitudes:Examination of the relationship between measures of intergroup bias.Blackwell Handbook of Social Psychology:Intergroup Processes,4,175–197.

[25]. Steger,M.F.,Frazier,P.,Oishi,S.,&Kaler,M.(2006).The Meaning in Life Questionnaire:Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life.Journal of Counseling Psychology,53,80-93.

[26]. Greenwald,A.G.,McGhee,D.E.,&Schwartz,J.L.K.(1998).Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition:The implicit association test.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,74(6),1464–1480.https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1464

[27]. Borys,S.,&Perlman,D.(1985).Gender Differences in Loneliness.Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin,11(1),63–74.https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167285111006

[28]. Nosek,B.A.(2007).Implicit–Explicit Relations.Current Directions in Psychological Science,16(2),65–69.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00477.x

Cite this article

Zhou,Q. (2023). Implicit and Explicit Loneliness among Young Adults: The Role of Life Meaning. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,3,828-834.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Educational Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries (ICEIPI 2022), Part II

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Russell,D.,Peplau,L.A.,&Cutrona,C.E.(1980).The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale:Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,39(3),472–480.https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.472.

[2]. Weiss,R.S.(1974).The provisions of social relationships.In Z.Rubin(Ed.),Doing unto others(pp.17-26).Englewood Cliffs,NJ:Prentice-Hall.

[3]. Maslow,A.H.(1970).Motivation and Personality(2nd ed.).New York:Harper and Row.

[4]. Mushtaq,R.,Shoib,S.,Shah,T.,&Mushtaq,S.(2014).Relationship between loneliness,psychiatric disorders and physical health?A review on the psychological aspects of loneliness.Journal of clinical and diagnostic research:JCDR,8(9),WE01–WE4.https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2014/10077.4828

[5]. Goosby,B.J.,Bellatorre,A.,Walsemann,K.M.,&Cheadle,J.E.(2013).Adolescent Loneliness and Health in Early Adulthood.Sociological inquiry,83(4),10.1111/soin.12018.https://doi.org/10.1111/soin.12018

[6]. Twenge,J.M.,Haidt,J.,Blake,A.B.,McAllister,C.,Lemon,H.,&Le Roy,A.(2021).Worldwide increases in adolescent loneliness.Journal of adolescence,S0140-1971(21)00085-3.Advance online publication.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.06.006

[7]. Wilkinson,R.A.,&Chilton,G.(2013):Positive Art Therapy:Linking Positive Psychology to Art Therapy Theory,Practice,and Research,Art Therapy:Journal of the American Art Therapy Association,30:1,4-11

[8]. MaciàD,Cattaneo G,Solana J,Tormos JM,Pascual-Leone A and Bartrés-Faz D(2021).Meaning in Life:A Major Predictive Factor for Loneliness Comparable to Health Status and Social Connectedness.Front.Psychol.12:627547.doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.627547

[9]. Frankl,V.E.(1985).Man’s search for meaning(Revised and updated).New York,NY:Washington Square Press.

[10]. Krause N.(2004).Stressors arising in highly valued roles,meaning in life,and the physical health status of older adults.The journals of gerontology.Series B,Psychological sciences and social sciences,59(5),S287–S297.https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/59.5.s287

[11]. Sundström,M.,Edberg,A.K.,Rämgård,M.,&Blomqvist,K.(2018).Encountering existential loneliness among older people:perspectives of health care professionals.International journal of qualitative studies on health and well-being,13(1),1474673.https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2018.1474673

[12]. Schnell,T.,&Krampe,H.(2020).Meaning in Life and Self-Control Buffer Stress in Times of COVID-19:Moderating and Mediating Effects with Regard to Mental Distress.Frontiers in psychiatry,11,582352.https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.582352

[13]. Chen,X.,He,Y.,de Oliveira,A.M.,Coco,A.L.,Zappulla,C.,&Kasper,V.(2004).Loneliness and social adaptation in Brazilian,Canadian,Chinese,and Italian children:A multi-national comparative study.Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry,45,1373–1384.

[14]. Steger,M.F.,Kawabata,Y.,Shimai,S.,&Otake,K.(2008).The meaningful life in Japan and the United States:Levels and correlates of meaning in life.Journal of Research in Personality,42,660-678.

[15]. Zhao,J.,Song,F.,Chen,Q.,Li,M.,Wang,Y.,and Kong,F.(2018).Linking shyness to loneliness in Chinese adolescents:The mediating role of core self-evaluation and social support.Personality and Individual Differences,125,140-4.Doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.01.007

[16]. Lun,V.M.,&Bond,M.H.(2006).Achieving relationship harmony in groups and its consequence for group performance.Asian Journal of Social Psychology,9(3),195–202.

[17]. Victor,C.R.,&Yang,K.(2012).The prevalence of loneliness among adults:a case study of the United Kingdom.The Journal of psychology,146(1-2),85–104.https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2011.613875

[18]. Lee,C.M.,Cadigan,J.M.,&Rhew,I.C.(2020).Increases in Loneliness Among Young Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Association with Increases in Mental Health Problems.The Journal of adolescent health:official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine,67(5),714–717.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.009

[19]. Nausheen,B.,Gidron,Y.,Gregg,A.,Tissarchondou,H.S.,&Peveler,R.(2007).Loneliness,social support and cardiovascular reactivity to laboratory stress.Stress,10(1),37–44.https://doi.org/10.1080/10253890601135434.

[20]. Bargh,J.A.(1999).The cognitive monster:The case against the controllability of automatic stereotype effects.https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1999-02377-017

[21]. Greenwald,A.G.,&Banaji,M.R.(1995).Implicit social cognition:Attitudes,self-esteem,and stereotypes.Psychological Review,102(1),4–27.https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.102.1.4

[22]. Haeffel,G.J.,Abramson,L.Y.,Brazy,P.C.,Shah,J.Y.,Teachman,B.A.,&Nosek,B.A.(2007).Explicit and implicit cognition:a preliminary test of a dual-process theory of cognitive vulnerability to depression.Behaviour research and therapy,45(6),1155–1167.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2006.09.003

[23]. Kurdi,B.,Seitchik,A.E.,Axt,J.R.,Carroll,T.J.,Karapetyan,A.,Kaushik,N.,Tomezsko,D.,Greenwald,A.G.,&Banaji,M.R.(2019).Relationship between the Implicit Association Test and intergroup behavior:A meta-analysis.The American Psychologist,74(5),569–586.https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000364

[24]. Dovidio,J.F.,Kawakami,K.,&Beach,K.R.(2001).Implicit and explicit attitudes:Examination of the relationship between measures of intergroup bias.Blackwell Handbook of Social Psychology:Intergroup Processes,4,175–197.

[25]. Steger,M.F.,Frazier,P.,Oishi,S.,&Kaler,M.(2006).The Meaning in Life Questionnaire:Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life.Journal of Counseling Psychology,53,80-93.

[26]. Greenwald,A.G.,McGhee,D.E.,&Schwartz,J.L.K.(1998).Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition:The implicit association test.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,74(6),1464–1480.https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1464

[27]. Borys,S.,&Perlman,D.(1985).Gender Differences in Loneliness.Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin,11(1),63–74.https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167285111006

[28]. Nosek,B.A.(2007).Implicit–Explicit Relations.Current Directions in Psychological Science,16(2),65–69.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00477.x