1. Introduction

Platforms have gathered a rising number of digital workers. Digital labor was classified into 3 categories. First is the on-demand worker who accomplishes assignments distributed by the platform, such as uber driver or food delivery man. Second is the crowd worker who carries out artificial tasks like tagging photos behind the machine. The third is that social media laborers participate in social media platforms by producing content or interacting with others [1].

Former research around influencers either leveraged the economic frame, including a study on ‘like economy’ or explored the symbolic frame, like the discussion on queer women influencers and family influencers [2-4]. Moreover, a researcher, Casilli, noted influencers’ incitement on both economic and symbolic. Moreover, discussion on platforms’ impact on influencers from the labor perspective is necessary to understand the inner motivation of the new form of digital work and care for the future well-being of a wider range of digital laborers.

Zheng’s study on food delivery man reaffirmed the subjectivity of digital labor, while social media shows the differences [5]. On-demand and crowd workers follow the division of work and finish assignments dispatched by platforms—they are regular laborers working on digital platforms. However, influencers put constant effort into creating content and building online selves to accumulate followers on their social media accounts [6]. Besides regular works, their valuation includes fans and the impact of their social media accounts; they are new laborers working through platforms. Therefore, the labor relation of influencers is far more complicated than it seems.

An influencer’s work is less systematic than crowd work and less clear than on-demand work [1]. Compared with other forms of digital labor, influencers have more flexibility and creativity. Influencers’ success seems to be random, and everyone has the potential to affect millions of people through social media. In China, more than half of 95s people have listed social media influencers as their dream job [7]. The number of social media influencers is growing rapidly. The market size of influencer marketing has increased tenfold in recent years [8].

More than 9 million influencers have over 10 thousand followers in China, and most of them used to be full-time employees; several still have full-time jobs while being an influencer [9]. Analysis of employee turned influencer enables direct comparison of the working process and relations between workers and economic entities. This essay studies a real-life influencer who resigned from his full-time job in an advertisement agency. Through this case, two key aspects are studied to unveil platforms’ impact on social media influencers’ work and labor process: becoming an influencer, which hides the platform’s recessive management mechanism, and the salary-making model, which contains double-exploitation from both social media platform and advertisers.

2. An Employee-Turned Influencer Case

All social media influencers started from common platform user-producers, and it used to be two stages from common users to influencers who could make a living through posts on social media. The first is the fans-accumulation stage, followed by the commercialization stage. It is hard for user-producers to make money at the first stage, so most influencers start accumulating fans when they have a full-time job as employees, and then they turn to full-time influencers after making enough money through producing and posting commercial content.

James Ma is a typical employee-turned-influencer. James was a full-time employee in an advertisement agency in Shanghai; he resigned from his full-time job and became an independent social media influencer after generating enough fans on Douyin, the Chinese Tik Tok. From James’ experience, it is possible to dive deep labor process and labor relations with platforms and advertisers from the worker’s perspective.

2.1. From Users to Influencers: Invisible Capital-Labor Relations

Influencers are social media user-producers who gather large numbers of followers, and those followers are not limited to acquaintances like friends and family. Followers tend to have an emotional connection with influencers, which drives them to believe in influencers’ words or purchase products that influencers recommend. With the value of followers, influencers could get monetary rewards from advertisers by posting commercial content on their social media accounts.

Content is the main attraction toward fans, and content production is the basic work to become an influencer. In digital platforms, with the help of smartphones and creative applications, continuous content production is possible for ordinary users, while the visibility of content has become the main difficulty [10]. However, the iteration of content display and distribution on platforms have emphasized the importance of feeds and algorithm. Multiple Chinese social platforms, including Douyin, Xiaohongshu and Bilibili, presented their content in feeds. Instead of searching for content on these platforms, videos or articles are recommended and presented in feeds by the algorithm for users. The algorithm and the media are feeding users based on their historical views, likes, or influencers followed.

The algorithm plays an important role in motivating influencers’ continuous work for the platforms. The activity of accounts is a matrix influencing whether the system recommends influencers’ content to more users. Hence, James posts videos every two days on Douyin to maintain activity and get recommendations from the algorithm. Platforms’ power to impact the popularity of content through algorithms is not only a motivation for influencers to attract more followers but also potential exploitation of influencers’ free labor since 90% of regular posts on James’ social media accounts are not to make money but to maintain activity and visibility.

Stronger power in content distribution has enabled social media platforms to cultivate influencers. Traffic becomes the jetton of platforms to stimulate continuous and free labor from numerous social media users. Suppose users want to gain traffic support from the platform to get more fans. In that case, they need to follow the platform’s operation guide, including posting on Douyin on a regular or even a daily basis or joining trending hashtag topics to generate more attention. All these efforts from user-producers would enrich platforms’ supply of content to common social media users.

Platforms even set up standards that influencers need to meet before they are qualified to receive commercial assignments and get monetary rewards from advertisers. The basic standard Douyin influencers face is the number of followers. According to Douyin, influencers’ follower count determines the capability of commercialization. When influencers get more than 1 thousand fans, they could earn money through live-streaming assignments; short video assignments would be available when the fans count increased to 10 thousand, and customized requests from advertisers would be available for influencers who have more than 100 thousand fans. Diverse commercialization assignments stand for a different level of monetary rewards; hence influencers tried their best to reach the highest fans count criteria set by platforms to win the maximum possibility on their salary.

Take James as an example; he started Douyin in March 2020, posting about the English language and his oversea study experience. At the end of 2020, his account gathered 38,000 fans without monetary investment. James quit his full-time in Feb. 2022 and became an influencer when his Douyin account got over 100 thousand fans. He planned the process of career transition based on the platforms’ regulation of influencer commercialization.

Platforms’ guides and regulations are not compulsory, while control over traffic turns platforms into capital authority for influencers, from whom they get traffic and followers as rewards by providing content production work. Hence, although there are no physical contracts between platforms and influencers, capital-labor relations are still existing.

Traffic is the key for platforms to hold invisible power over influencers, while the traffic is determined by user volume and usage duration. Platforms gathered common users’ attention and turned it into the capital to drive free labors who wanted to become influencers. Content produced by these free user-producers would attract more users and extend their time spending on platforms. In this whole process, platforms are gaining numerous users, growing attention, and free content; they are paying technology and operation costs but no direct monetary cost to user-producers.

2.2. Influencer’s Salary-making Model and Dual-exploitation Behind

Social media influencers could earn money through platforms as digital labor, while their monetary rewards are not from digital platforms directly, and that is the main difference between traditional content producers like magazine writers or television directors, whose salaries are paid by media platforms directly.

When James was working in an advertisement agency, he undertook multiple types of work, including script writing, video shooting, and copywriting, as well as brands’ social media account operation, and those works had few differences from his current work as a social media influencer. However, the source of his income has changed much -- he used to get a salary from the company as an employee, and now he earns money from advertisers through commercial content.

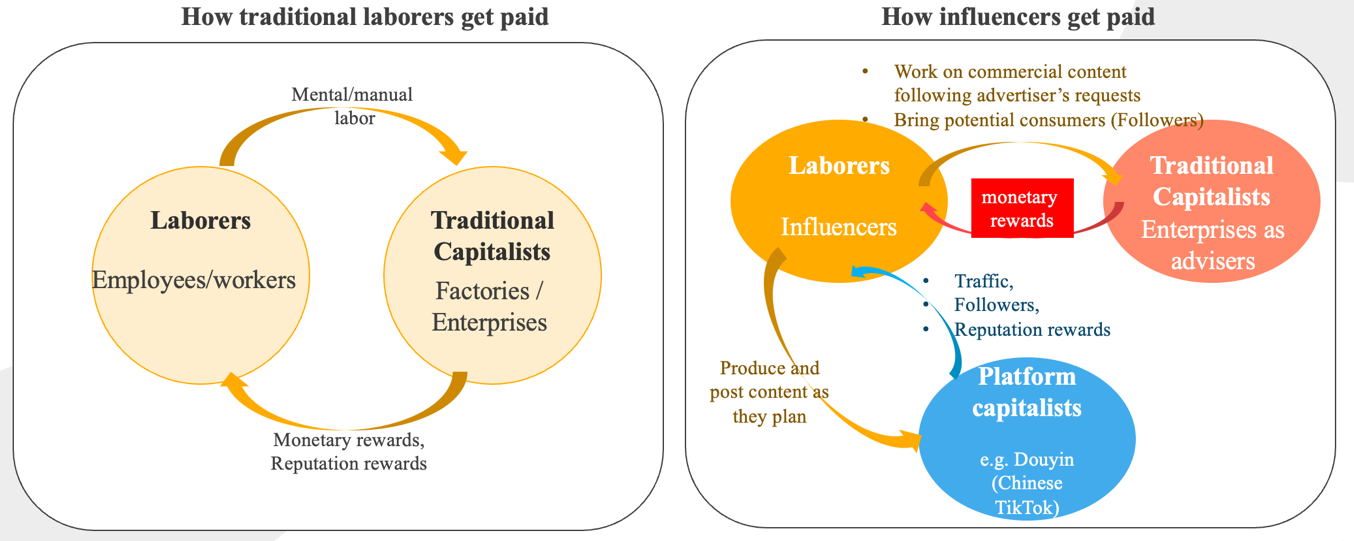

Figure 1: Comparison of the salary-making model of employees and influencers.

Figure 1 shows the exchange of labor and salary between laborers and capitalists. Traditional laborers, like employees or workers, provide mental/manual labor to traditional capitalists, including companies and factories and get salaries directly from the capitalists they work for. Laborers also get psychological rewards, including respect from colleagues and a sense of self-accomplishment through fulfilling extra goals [5]. This two-way exchange happens in regular employment relations.

Influencers like James, who have relations with both platform capitalists and traditional capitalists, are facing dual exploitation. First, in the exchange relations with platform capitalists, influencers work to provide online content for platforms to get followers or recognition from platforms, and that is the foundation of getting monetary rewards from their social media accounts. Second, in the other exchange relations with traditional capitalists, influencers put work into fulfilling assignments given by advertisers, who are corporate in general. These assignments fundamentally include producing and posting commercial content on influencers’ accounts; in certain circumstances, advertisers might request influencers to encourage fans to purchase products from the advertisers.

Influencers would get monetary rewards from advertisers after publishing the commercial content. While influencers’ wages are not paid in a fixed time—neither the beginning nor the end of a month. The payment process would start once the advertiser affirmed that the commercial content produced by the influencer is qualified. Influencers are not getting salaries from advertisers directly. Advertisers pay influencers’ salaries on platforms like Douyin Xintu, which is an advertiser and influencer matching platform attached to Douyin, and influencers would get their salary from this platform. During this process of labor and salary exchange, platforms charge several percentages of the service fees. This service fee is also the main monetary profit that social media platforms are earning in influencer marketing.

Platforms’ control over payment days has virtually become a measure to manage the output of influencers’ commercial content. Once advertisers complain that influencers are not fulfilling their requests, platforms could postpone payment until influencers finish work according to advertisers’ standards. Sometimes complaint from advertisers means influencers have to work overtime or even rework.

Influencers’ relationship with both platform capitalists and traditional capitalists has complicated the exploitation situation faced by influencers. On the one hand, they are driven to provide social media platforms with free and high-quality content continuously to maintain the capability to be seen on the platforms. On the other hand, they are required to serve advertisers based on their requests strictly to get their salary through the platform on time.

3. The Development of New Labor-Capital Relations on Social Media Platforms

Compared with traditional labor, social media influencers have distinctive relations with capitalists. Platforms provide common users chances to become popular and make money, which request users to simply post content on their own social media accounts. It seems influencers have higher subjectivity and freedom than traditional employees—they can choose when and what to post, and they have full copyright and ownership of their social media work and account. However, platform capitalists have established and applied covert management mechanisms to drive influencers as free digital labor in the way platforms want.

3.1. The Control through Visibility

Capitalists used to control laborers’ behavior and motivate traditional laborers through wages and bonuses. While it is hard for social media platforms to manage influencers, whose monetary rewards are from advertisers through salary. Platforms need the jetton, other than money, to drive constant digital labor and user-generated content, and visibility becomes the key since it is fundamental for growing social media users’ number of fans, which is the pivotal asset for lucrative influencers.

Through feeds and algorithm technology, social media platforms could determine the content presented to users, and this capability turned into powers of supporting influencers. Operation guides from platforms to influencers become the golden rule in the fans-accumulation stage, and these guides encourage influencers to put efforts in the way platforms want them to, including posting more well-made content on a regular base.

3.2. The Price of Autonomy

Laborers’ tendency to choose works that are more flexible in time and more subjective in outcomes has implied the direction of contemporary labor reallocation—a deeper pursuit of freedom and self-value under a survival premise. This freedom has surpassed freedom of purchase in the context of consumerism, and self-value has surpassed respect for privilege in the context of capitalism. The pursuit contains workers’ yearning for positive work-leisure relations: work for leisure and leisure for maximum freedom.

Full-time workers devoting spare time to becoming influencers manifests the increasing subjectivity of modern laborers. They are no longer satisfied with a steady job that provides a monthly salary and desire to chase the highest level of freedom and self-accomplishment in the limited number of working hours. With the increasing acknowledgement of capitalism, some laborers have realized the limitation of consultative revolution, such as flextime for work-life balance. They turn to an essential self-transform to escape from being controlled by capital.

Digital platforms advocating freedom of creation have spawned self-development and self-employment among users, providing alternatives for laborers by lowering the content production and monetization barrier. User-producers could earn the chance to surpass the nine-to-five routines to manage their time and make a living through their creation; even they would be paying free labor to the social media platforms. Working as social media influencers stimulate the laborer’s autonomy since most influencers create their accounts from scratch and mainly based on their preferences. James, the influencer, could determine working hours, video theme, shoot style, and more. Traditional workplaces manage the human body and behavior, while influencers could experience freedom in creating their social media accounts and content after the experience of unfreedom in the traditional workplace [11].

However, James had very limited control over working when he was working for an advertisement agency. Hence the autonomy of influencers is not limitless since commercial content has exacting requirements for influencers to meet. To make enough money through social media platforms and switch from a full-time job to a more flexible working style, influencers have no other choice but to fulfill advertisers’ requests. Traditional laborers trade power surrendered in the sphere of production and got money as makeshift power, and digital laborers get limited autonomy on platforms surrendering partial freedom of creation.

4. Conclusions

Contemporary laborers have the tendency to break away from capital control to pursue self-control and self-achievement. Platforms provide alternatives for workers, which have driven the mushrooming of social media influencers. Influencers are facing dual exploitation from both platforms and advertisers. Platforms have invisible control over user-producers through technology and algorithm, which they use to drive users’ continuous free labor and prolong exploitation periods of the working process. Advertisers are the major salary source for influencers, and influencers give away partial freedom of creative content production, providing commercial content in exchange for freedom in daily creation.

It is essential to understand platforms’ invisible control of social media laborers through technology and algorithm, as well as the dual exploitation that influencers are facing. James’s case is typical enough in terms of the labor process and labor-capital relations of social media influencers, while the universality of laborers’ motivation in this research still needs further verification due to the limitation in the number of influencers as research objects.

Based on the cognition of complex labor-capital relations that social media influencers are facing, three directions of research are necessary. First, further research on the platforms’ management system for new laborers, including reward and punishment system, content production introduction, and technology’s role in the system. Second, the protection of social media laborer’s rights, as neither labor contracts nor clear salary regulation is available for influencers when they work for platforms, which would lead laborers into uncertainty and labor-pay inequality. Third, research on digital laborers’ vision of work to reform the labor system accordingly and fulfill the well-being of a wide range of new laborers.

References

[1]. Fagioli, A. (2021) To exploit and dispossess: The twofold logic of platform capitalism. Work organization, labour & globalization.15(1), 126-137.

[2]. Gerlitz, C., Helmond, A. (2013) The like economy: Social buttons and the data-intensive web. New media & society, 15(8), 1348-1365.

[3]. Duguay, S. (2019) “Running the numbers”: Modes of microcelebrity labor in queer women’s self-representation on Instagram and Vine. Social media+ society, 5(4), 2056305119894002.

[4]. Abidin, C. (2017) # familygoals: Family influencers, calibrated amateurism, and justifying young digital labor. Social Media+ Society, 3(2), 2056305117707191.

[5]. Zheng, S. X. (2021) The “Sacred Labor” that is stared at and ignored--re”—— Anthropological comparison and reflection on the study of delivery riders. New Vision, 6), 77-83.

[6]. Fuchs, C. (2021) Social Media: A Critical Introduction.3rd ed. UK: SAGE Publication Ltd.

[7]. Xinhua net. (2017) 95s generation’s notion of employeement.Xinhuanet.com.Retrieved from http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2017-04/24/c_1120860496.htm

[8]. Satora, A. (2023) Key Influencer Marketing Statistics to Drive Your Strategy in 2023. Retrieved from https://influencermarketinghub.com/influencer-marketing-statistics/

[9]. IMS. (2021) Chinese influencer economy development report. Retrieved from https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP202108021507528798_1.pdf

[10]. Sun, P., Qiu, L. C., Yu, H. Q. (2021) Platform as A Method:Labour, Technology and Communication. Journalism and Communication,28,8-24.

[11]. Bauman, Z. (1983) Industrialism, consumerism and power. Theory, Culture & Society, 1(3), 32-4.

Cite this article

Zhang,Y. (2023). Free to Be Bound: Labor Relations and Labor Process of Social Media Influencers. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,8,334-339.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Fagioli, A. (2021) To exploit and dispossess: The twofold logic of platform capitalism. Work organization, labour & globalization.15(1), 126-137.

[2]. Gerlitz, C., Helmond, A. (2013) The like economy: Social buttons and the data-intensive web. New media & society, 15(8), 1348-1365.

[3]. Duguay, S. (2019) “Running the numbers”: Modes of microcelebrity labor in queer women’s self-representation on Instagram and Vine. Social media+ society, 5(4), 2056305119894002.

[4]. Abidin, C. (2017) # familygoals: Family influencers, calibrated amateurism, and justifying young digital labor. Social Media+ Society, 3(2), 2056305117707191.

[5]. Zheng, S. X. (2021) The “Sacred Labor” that is stared at and ignored--re”—— Anthropological comparison and reflection on the study of delivery riders. New Vision, 6), 77-83.

[6]. Fuchs, C. (2021) Social Media: A Critical Introduction.3rd ed. UK: SAGE Publication Ltd.

[7]. Xinhua net. (2017) 95s generation’s notion of employeement.Xinhuanet.com.Retrieved from http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2017-04/24/c_1120860496.htm

[8]. Satora, A. (2023) Key Influencer Marketing Statistics to Drive Your Strategy in 2023. Retrieved from https://influencermarketinghub.com/influencer-marketing-statistics/

[9]. IMS. (2021) Chinese influencer economy development report. Retrieved from https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP202108021507528798_1.pdf

[10]. Sun, P., Qiu, L. C., Yu, H. Q. (2021) Platform as A Method:Labour, Technology and Communication. Journalism and Communication,28,8-24.

[11]. Bauman, Z. (1983) Industrialism, consumerism and power. Theory, Culture & Society, 1(3), 32-4.