1. Introduction

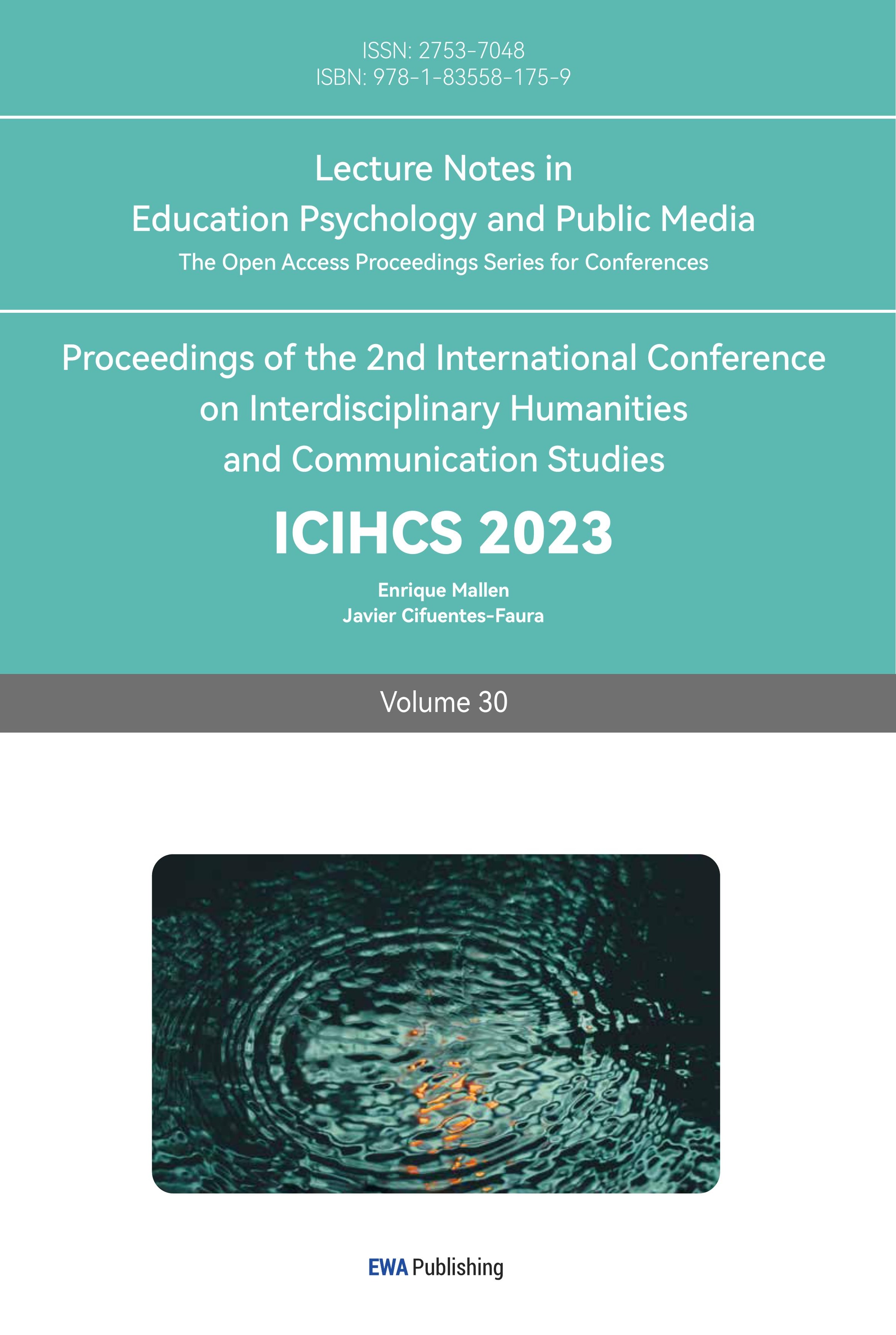

In the past century, there has been a remarkable surge in urban populations worldwide. According to data, the global urban population skyrocketed from 1 billion to 2.9 billion in the latter half of the 20th century, reaching a staggering 3.6 billion by 2010. Presently, more than half of the global population resides in urban areas, highlighting the significance of understanding urbanization trends and their impacts.[1]

This essay will delve into a comprehensive comparative and contrastive analysis of the rapid urbanization witnessed in "Less Developed Countries" (LDCs) over the last 50 years, juxtaposed with the striking urban growth experienced in 19th-century Britain. By closely examining the contextual, causal, and consequential aspects of these phenomena, we aim to extract valuable insights that can inform contemporary urban development strategies.

Understanding the contextual differences between urbanization in LDCs and 19th-century Britain is crucial. The historical, economic, and sociopolitical contexts of these periods profoundly shaped the nature and pace of urbanization. Factors such as industrialization, technological advancements, colonization, and globalization played distinct roles in each scenario, affecting the patterns and dynamics of urban growth.

Figure 1: Line graph of the growth of urban population in the world during 1960 to 2015 which estimated by World Bank staff [1].

2. Comparison and Contrast in Context

LDCs share key traits: Low Per Capita Income, Capital Shortage, Population Explosion, and Low Productivity. Malthus' 1798 prediction about population growth rings true in most of these countries.[2] After World War II, mortality in many developing nations dropped rapidly, partly due to improved healthcare, resulting in a significant decline in death rates but not in birth rates,[3] ultimately causing a surge in population growth since the 1950s. [4]

Globally, urbanization is on the rise. In 1950, 29% of the world lived in urban areas; by the late 2000s, it was around 49%.[5] In the 19th century, Britain experienced a growth rate comparable to LDCs over the previous 50 years, driven not by shifts in birth and death rates, but by the transformative British Industrial Revolution, starting in the 1760s with innovations in the cotton textile industry and the widespread adoption of Watt steam engines, symbolizing a mechanization revolution in the 1830s and 1840s.[6]

Figure 2: Industrial agriculture [6].

In the 17th century, the British bourgeois regime propelled capitalist development and colonial expansion, amassing significant capital. The Enclosure Movement provided essential labor, supplemented by immigration from rural areas and foreign nations, bolstering the population.[7]

Comparing LDCs and 19th century Britain, both experienced a notable urban population surge. However, 19th century Britain thrived in a pivotal era of technological and industrial revolution, drawing a substantial working-class population to address livelihood challenges. Conversely, LDCs in the past 50 years faced poverty, capital scarcity, and low productivity, differing greatly from Britain's 19th-century context.[8]

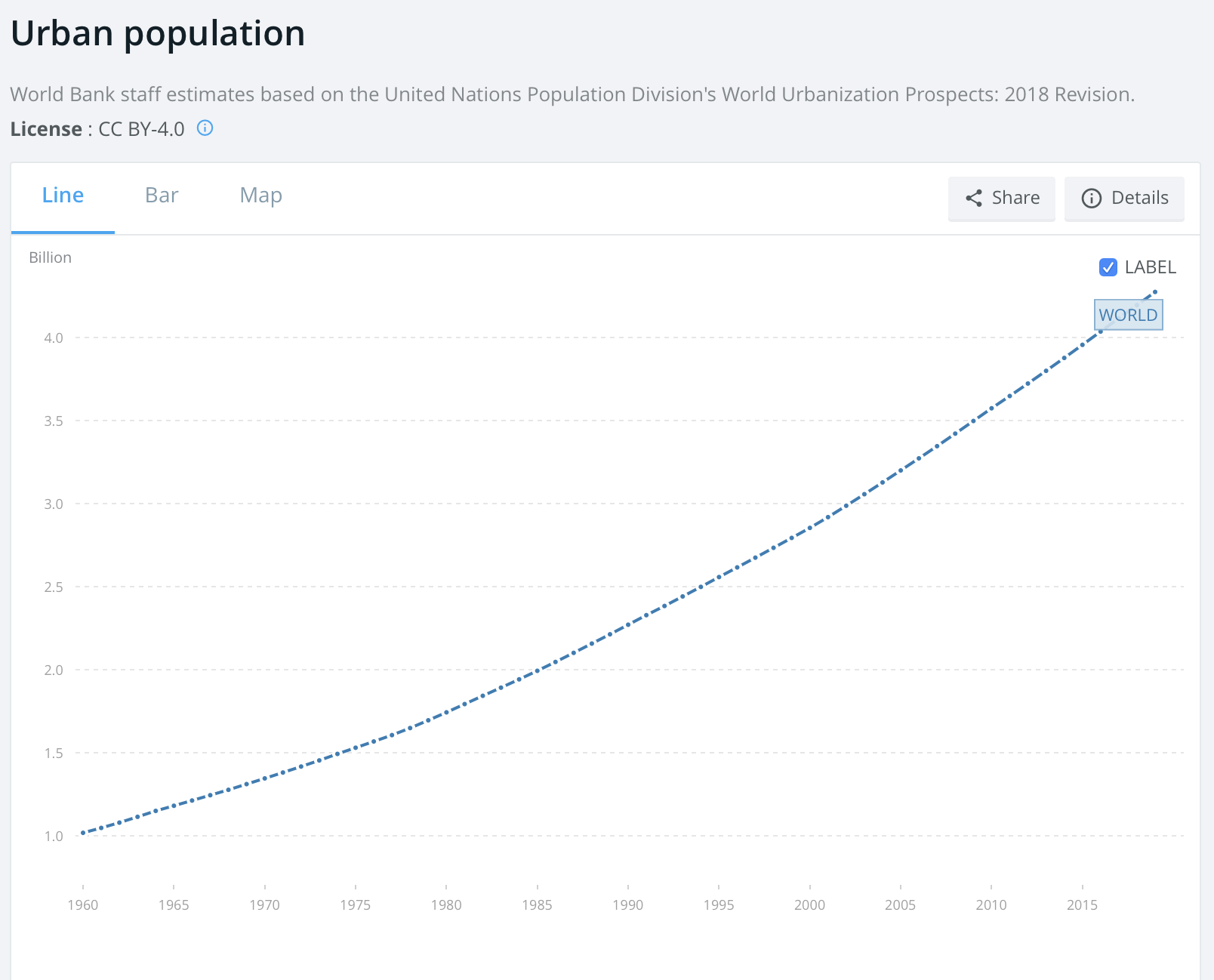

Figure 3: Map of different classes which live in different part in London [9].

Although urban population growth in 19th century Britain and LDCs in the last 50 years has produced many positive effects, there are also some problems and challenges in urban planning. By contrast, the urban population growth in Britain is more active, while in less developed countries is relatively passive.

3. Comparison and Contrast in Causes

“Population Explosion and High Dependence” are one of the main characteristics of LDCs.[10]

Figure 4: Poverty in Less Developed Country [11].

Rural areas face limited prospects, pushing migration to resource-rich urban centers. The "pull" of cities includes better living standards, opportunities, high-paying jobs, healthcare, and education, attracting rural inhabitants.[11]

Towards the end of the British Industrial Revolution, stability in technological and industrial development became the dominant "pull" factor. However, precarity was prevalent before the revolution, indicating a marginal subsistence existence for the masses in any nation.[12] Historical evidence showcases Britain's pre-industrial poverty, both in urban and rural contexts.

The Enclosure Movement marked a pivotal phase, where a new aristocracy privatized land, displacing peasants and transforming them into the proletariat, accelerating urban population due to ample employment opportunities from industrialization.[13]

The heart of the Industrial Revolution in Britain lay in the shift from handicraft industries to large-scale machine-based factories, significantly altering the industrial landscape.[14] The revolution demanded a substantial labor force, and urban areas, offering numerous employment prospects, saw a rapid population surge.

Similarities between urban population growth in LDCs and 19th-century Britain include push and pull factors. In LDCs, the stronger "push" is due to pervasive poverty, compelling people to seek new opportunities. Conversely, Britain's trajectory showed a gradual escape from poverty towards a new phase of development, amplifying the "pull" of urbanization.[11]

4. Comparison and Contrast in Effects

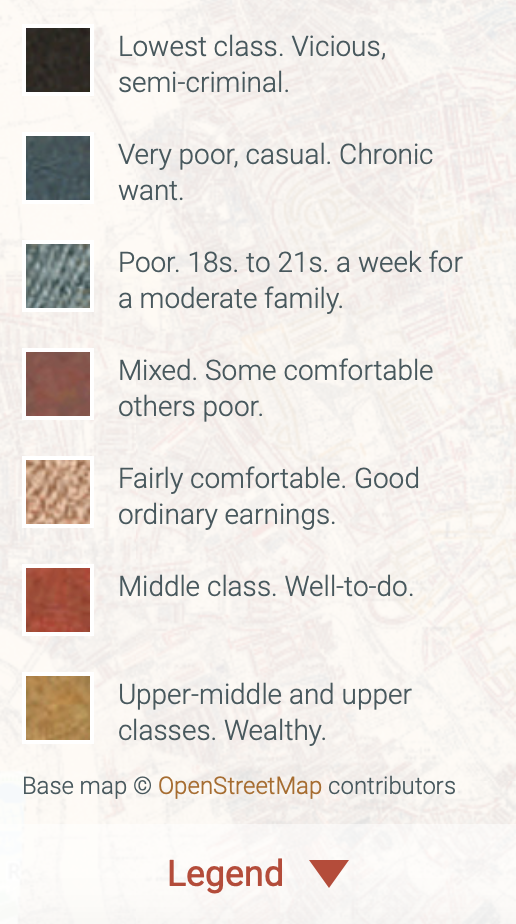

“Large cities will play a significant role in absorbing future anticipated growth, but for the foreseeable future the majority of urban residents will still reside in much smaller urban settlements of fewer than 500,000 residents. (see the image below)” [15]

Figure 5: Size of Urban Settlement [15].

The effect is the urban settlements gradually dwindled and were not enough to provide for all the urban residents, while many people of the working class with low incomes had to live in slums. The reduction of water supply in many surrounding urban areas and slums has become a major challenge.[16]

The sudden expansion in urban populations also has some effects on urban development. For example, traffic jams (In Sao Paulo, Brazil, the government has passed such a law that only certain vehicles are allowed to drive on the streets according to their license plate number), air pollution (It is estimated that 60% of Kolkata's residents suffer from respiratory diseases related to air pollution; The World Bank estimates that only 35 percent of urban residents in developing countries have adequate health services).[16]

Figure 6: Air pollution in Kathmandu [17].

Revisionist economists, drawing from sectoral studies, argue that rapid population growth isn't a primary barrier to economic development. Instead, it interacts with and worsens failings in economic and social policy, with effects varying by context.[18]

While urban population growth appears to drive GDP and productivity in LDCs, the root issue remains underdevelopment and poverty. In the 19th century, Britain faced similar challenges due to urban population growth, notably housing shortages. London's population doubled from 1801 to 1851, causing overcrowded, unsanitary living conditions.[19].

Figure 7: Housing problem [20].

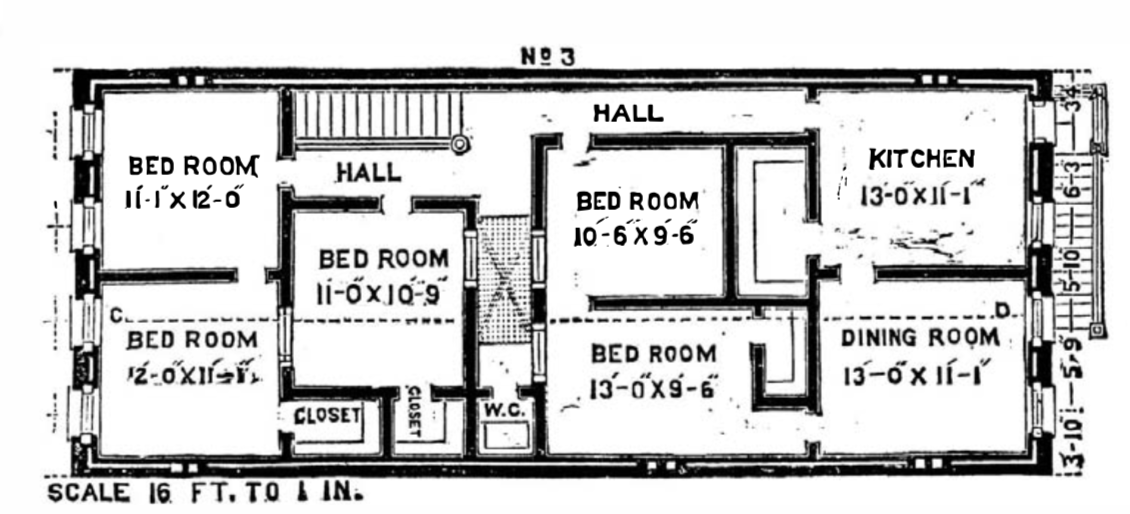

From the plan, it seems that five families will live on one floor. They have to share the kitchen, living room, and toilet, which is very crowded, rough, and lacks privacy. In such an environment, the physical health of residents will be affected seriously. (see the image below)

Figure 8: Plan of a working-class house [21].

However, the rapid growth of the urban population provided a rising labour force to facilitate the introduction of intensive agriculture, as well as to mine coal and work in factories.

Figure 9: Factory in the Industrial Revolution [22].

A growing market for the necessities of life (food, clothes, shelter, and household goods) was provided, encouraging entrepreneurs to experiment with new techniques to enable them to produce more, faster, and cheaper. This steadily expanding domestic market exerted a valuable cushioning effect whenever volatile export markets underwent a temporary recession.[22]

The striking difference between LDCs is that what they lack is in such a resource-rich society, which leads to the essential difference in the effect of 19th-century urban population rapid growth in Britain and the last 50 years of urban population growth in LDCs.

5. Conclusion

LDCs face poverty aggravated by rapid urban population growth, unlike Britain in the 19th century, where the Industrial Revolution lifted them from poverty. Comparative studies reveal the fundamental difference in urban population growth between 19th century Britain and LDCs in the last 50 years, attributed to distinct social systems and natures.

References

[1]. The World Bank, World Bank Group, 1945, accessed January 4, 2021, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL?end=2019&start=1960&type=shaded&view=chart&year=1993

[2]. S, Nipun, Economics Discussion, Economics Discussion, accessed January 3, 2021, https://www.economicsdiscussion.net/economic-growth/less-developed-countries-ldcs-economics/26295

[3]. Britannica, Britannica Group, Inc., 2001, accessed January 3, 2021, https://www.britannica.com/science/population-biology-and-anthropology/The-developing-countries-since-1950

[4]. Grospelier, Joelle, “Population Growth In Less Developed Countries”, Student Economic Review, Vol. 17, (2003), pp. 187-196, page 188.

[5]. Rafferty, John P., Britannica, Britannica Group, Inc., 2001, accessed January 3, 2021, https://www.britannica.com/topic/urban-sprawl

[6]. History, A&E TELEVISION NETWORKS, LLC, accessed December 30, 2020, https://www.history.com/topics/industrial-revolution/industrial-revolution#&gid=ci0230e631d0342549&pid=harvesting-cotton

[7]. White, Matthew, British Library, British Library Council, October 14, 2009, accessed December 29, 2020, https://www.bl.uk/georgian-britain/articles/the-industrial-revolution#

[8]. Nipun S, Economics Discussion, Economics Discussion, accessed January 3, 2021, https://www.economicsdiscussion.net/economic-growth/less-developed-countries-ldcs-economics/26295

[9]. LSE Library Charles Booth’s London, London School of Economics & Political Science, accessed October 26, 2020, https://booth.lse.ac.uk/learn-more/download-maps

[10]. Microsoft Bing, Microsoft, 2009, accessed January 3, 2021, https://cn.bing.com/images/search?view=detailV2&ccid=I%2bkovjwc&id=8D9952085951BD470B2F7F9F6F421D9EB34C85AE&thid=OIP.I-kovjwcgge1VCyjljVilgAAAA&mediaurl=https%3a%2f%2fodishanewsinsight.com%2fwp-content%2fuploads%2f2015%2f10%2fglobal-poverty.jpg&exph=315&expw=355&q=poverty&simid=607988561545792334&ck=0726147DC9357D765C767CADC2E1CFF5&selectedIndex=6&FORM=IRPRST&ajaxhist=0

[11]. Mondal, Puja, Your Article Library, Your Article Library, accessed January 2, 2021, https://www.yourarticlelibrary.com/society/urbanization-in-developed-and-developing-countries-around-the-world/4678

[12]. Mathias, Peter, The First Industrial Nation- The Economic History Of Britain 1700-1914 (New York: Routledge, 2001), page 4.

[13]. Knox, W. W. J., ResearchGate, ResearchGate GmbH, accessed December 28, 2020, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237444349_A_HISTORY_of_the_SCOTTISH_PEOPLE_THE_SCOTTISH_EDUCATIONAL_SYSTEM_1840_-_1940.

[14]. Baidu baike, Baidu, April 20, 2006, accessed December 26, 2020, https://baike.baidu.com/item/英国工业革命/6047101?fr=aladdin.

[15]. Cohen, Barney, “Urbanization in developing countries: Current trends, future projections, and key challenges for sustainability”, Technology in Society, 28 (2006), page 73–74.

[16]. Assignment Point, Assignment Point, accessed January 3, 2021, https://www.assignmentpoint.com/arts/modern-civilization/causes-of-urban-growth.html

[17]. The farsight, The farsight, accessed January 3, 2021, https://www.farsightnepal.com/2020/05/27/kathmandus-lethal-pollution-is-its-greatest-economic-adversary/

[18]. Joelle Grospelier, “Population Growth In Less Developed Countries”, Student Economic Review, Vol. 17, (2003), pp. 187-196, page 191.

[19]. Wilde, Robert, ThoughtCo., About, Inc., accessed January 5, 2020, https://www.thoughtco.com/population-growth-and-movement-industrial-revolution-1221640

[20]. Elton, Arthur & Anstey, E. H., “HOUSING PROBLEMS”, vimeo, 1935, accessed September 21, 2020, https://vimeo.com/4950031

[21]. “THE HOMES OF THE WORKING CLASSES”, Scientific American, Vol. 32, No. 25 (June 19, 1875), pp. 391-392.

[22]. History Crunch, History Crunch, accessed January 2, 2020, https://www.historycrunch.com/why-was-britain-the-first-country-to-industrialize.html

Cite this article

Liu,Z. (2023). Comparing Urban Population Growth: Less Developed Countries in the Last 50 Years and the 19th Century Britain. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,30,189-195.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. The World Bank, World Bank Group, 1945, accessed January 4, 2021, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL?end=2019&start=1960&type=shaded&view=chart&year=1993

[2]. S, Nipun, Economics Discussion, Economics Discussion, accessed January 3, 2021, https://www.economicsdiscussion.net/economic-growth/less-developed-countries-ldcs-economics/26295

[3]. Britannica, Britannica Group, Inc., 2001, accessed January 3, 2021, https://www.britannica.com/science/population-biology-and-anthropology/The-developing-countries-since-1950

[4]. Grospelier, Joelle, “Population Growth In Less Developed Countries”, Student Economic Review, Vol. 17, (2003), pp. 187-196, page 188.

[5]. Rafferty, John P., Britannica, Britannica Group, Inc., 2001, accessed January 3, 2021, https://www.britannica.com/topic/urban-sprawl

[6]. History, A&E TELEVISION NETWORKS, LLC, accessed December 30, 2020, https://www.history.com/topics/industrial-revolution/industrial-revolution#&gid=ci0230e631d0342549&pid=harvesting-cotton

[7]. White, Matthew, British Library, British Library Council, October 14, 2009, accessed December 29, 2020, https://www.bl.uk/georgian-britain/articles/the-industrial-revolution#

[8]. Nipun S, Economics Discussion, Economics Discussion, accessed January 3, 2021, https://www.economicsdiscussion.net/economic-growth/less-developed-countries-ldcs-economics/26295

[9]. LSE Library Charles Booth’s London, London School of Economics & Political Science, accessed October 26, 2020, https://booth.lse.ac.uk/learn-more/download-maps

[10]. Microsoft Bing, Microsoft, 2009, accessed January 3, 2021, https://cn.bing.com/images/search?view=detailV2&ccid=I%2bkovjwc&id=8D9952085951BD470B2F7F9F6F421D9EB34C85AE&thid=OIP.I-kovjwcgge1VCyjljVilgAAAA&mediaurl=https%3a%2f%2fodishanewsinsight.com%2fwp-content%2fuploads%2f2015%2f10%2fglobal-poverty.jpg&exph=315&expw=355&q=poverty&simid=607988561545792334&ck=0726147DC9357D765C767CADC2E1CFF5&selectedIndex=6&FORM=IRPRST&ajaxhist=0

[11]. Mondal, Puja, Your Article Library, Your Article Library, accessed January 2, 2021, https://www.yourarticlelibrary.com/society/urbanization-in-developed-and-developing-countries-around-the-world/4678

[12]. Mathias, Peter, The First Industrial Nation- The Economic History Of Britain 1700-1914 (New York: Routledge, 2001), page 4.

[13]. Knox, W. W. J., ResearchGate, ResearchGate GmbH, accessed December 28, 2020, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237444349_A_HISTORY_of_the_SCOTTISH_PEOPLE_THE_SCOTTISH_EDUCATIONAL_SYSTEM_1840_-_1940.

[14]. Baidu baike, Baidu, April 20, 2006, accessed December 26, 2020, https://baike.baidu.com/item/英国工业革命/6047101?fr=aladdin.

[15]. Cohen, Barney, “Urbanization in developing countries: Current trends, future projections, and key challenges for sustainability”, Technology in Society, 28 (2006), page 73–74.

[16]. Assignment Point, Assignment Point, accessed January 3, 2021, https://www.assignmentpoint.com/arts/modern-civilization/causes-of-urban-growth.html

[17]. The farsight, The farsight, accessed January 3, 2021, https://www.farsightnepal.com/2020/05/27/kathmandus-lethal-pollution-is-its-greatest-economic-adversary/

[18]. Joelle Grospelier, “Population Growth In Less Developed Countries”, Student Economic Review, Vol. 17, (2003), pp. 187-196, page 191.

[19]. Wilde, Robert, ThoughtCo., About, Inc., accessed January 5, 2020, https://www.thoughtco.com/population-growth-and-movement-industrial-revolution-1221640

[20]. Elton, Arthur & Anstey, E. H., “HOUSING PROBLEMS”, vimeo, 1935, accessed September 21, 2020, https://vimeo.com/4950031

[21]. “THE HOMES OF THE WORKING CLASSES”, Scientific American, Vol. 32, No. 25 (June 19, 1875), pp. 391-392.

[22]. History Crunch, History Crunch, accessed January 2, 2020, https://www.historycrunch.com/why-was-britain-the-first-country-to-industrialize.html