1. Introduction

The COVID-19 negatively impacts the world's economy in a variety of aspects. For instance, the economic crisis in the U.S. is unprecedented in its scale: the pandemic has created a demand shock, a supply shock, and a financial shock all at once. The pandemic has created a demand shock, a supply shock, and a financial shock all at once. The BEA reported that the second quarter of 2020 saw the most dramatic decline in economic output since records began, with a contraction of 9.1 percent. The second quarter of 2020 saw the most dramatic decline in economic output since records began, with a contraction of 9.1 percent. The BEA reported that the second quarter of 2020 saw the most dramatic decline in economic output since records began, with a contraction of 9.0 percent. This paper aims to analyze the movement in the sovereign bond market resulting from such actions and policies and then further explain the status of the U.S. economy during the last decade. Finally, it analyzed the movement in the sovereign bond market resulting from such actions and policies and further explained the status of the U.S. economy during the COVID-19 panic.

2. Literature review

US Treasury bonds, also known as US government bonds, refer to the debt securities issued by the US government to raise funds for its expenditures and fiscal needs. These bonds are considered borrowing instruments, where the government issues them to investors, effectively borrowing money. In return, the government promises to repay the principal amount along with interest over a specified period of time. US Treasury bonds possess the following characteristics and definitions: borrowing Nature: US Treasury bonds serve as a means for the government to borrow funds. The funds raised through these bonds are used to fulfill various national expenditures, such as infrastructure development, social welfare, healthcare, and more.

3. Types of bonds and their role

3.1. Types of Bonds

Types of Bonds: The US government can issue different types of Treasury bonds, including short-term, medium-term, and long-term bonds. Each type of bond has a distinct maturity period and interest rate structure.

Interest Payments: The US government pays interest to the holders of Treasury bonds as compensation. Interest is typically paid at a fixed rate to bondholders, making Treasury bonds a relatively stable investment option.

3.2. The role of bonds

Security: US Treasury bonds are considered highly secure investment instruments due to the backing of the US government. The high credit rating of the US government makes Treasury bonds virtually free from default risk.

Liquidity: The market for US Treasury bonds is highly active, allowing for easy buying and selling of bonds. Investors can buy or sell Treasury bonds in the market with relative ease.

Source of Government Expenditure: The issuance of US Treasury bonds serves to meet the funding requirements of government expenditures, including addressing fiscal deficits, supporting economic recovery, and investing in infrastructure. In summary, US Treasury bonds represent debt securities issued by the US government to raise funds for its expenditures. Investors can purchase these bonds to lend money to the government and receive interest returns in return. Treasury bonds are renowned for their high security and stability, making them a safe investment option. For the government, issuing Treasury bonds is a significant means of raising funds and meeting fiscal needs.

4. Social background

The U.S. government had a comprehensive response to the arrival of the epidemic. This paragraph will show the tangible impact of the relevant policies adopted by the U.S. government on the Treasury market and analyze the logic behind them. In the early stages of the outbreak, the economic situation in the US was volatile, and the following are some of the key economic indicators that were affected by the outbreak.

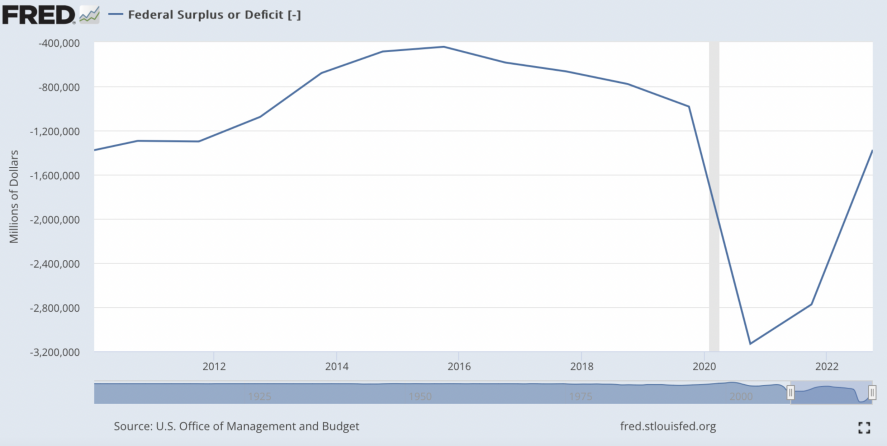

4.1. Government deficit

Firstly, the United States Government has experienced a shortage of funding in the two years since the epidemic outbreak [1]. As shown in the Figure 1. On 25 February 2020, Goldman Sachs (Goldman Sachs) lowered its forecast of United States gross domestic product (GDP) growth from 1.4 percent to 1.2 percent, pointing out that the epidemic would drag the United States economy. The International Monetary Fund's World Economic Outlook, released on 13 April 2020, forecasts the US economy to grow at -5.9% in 2020, below the world average of -3.0% [2]. Therefore, the U.S. government needs a lot of money to be put into the market to stimulate the U.S. economy, which is depressed under the epidemic. Secondly, the huge volume of costs of all types of epidemic prevention (medical resources, manpower, etc.) also requires a lot of money. On March 4, 2020, the US Congress announced an $8 billion emergency funding package, of which $3 billion was for vaccine research and development, treatments, and diagnostics, and $2.2 billion was for outbreak prevention and response efforts, etc. On March 6, Trump signed an $8.3 billion emergency spending bill to help the healthcare system. On March 18, Trump signed about $100 billion in emergency spending bills, including providing free virus tests to the public, increasing unemployment insurance rates, and allowing paid sick leave. On March 28, Trump signed a $2.2 trillion economic bailout package [3].

Figure 1: The U.S. Federal Deficit in 2020 [4]

Note: Covid-19 resulted in serious government deficit.

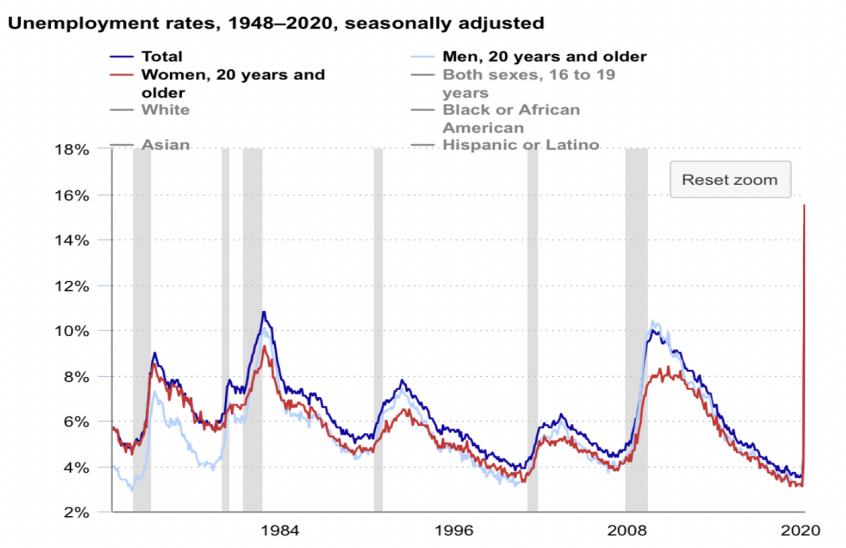

4.2. Unemployment

As suggested in Figure 2. Pre-epidemic employment was hit hard in the U.S. The economic blockade and social restrictions caused by the COVID-19 outbreak led to many business closures, layoffs, and employee pay cuts. Below are some key trends in employment:

(1). Unemployment soared: After the outbreak, unemployment rose rapidly in the U.S. In April 2020, the U.S. unemployment rate reached a historic peak of 14.8 percent. This is the highest unemployment rate since 1948 and is well above pre-epidemic levels.

(2). Employment in closed industries has been affected: industries closely related to face-to-face services, such as catering, hotel, tourism, retail, and aviation, have been hard hit by the epidemic, with many enterprises facing closure and layoffs. Employment in these industries has dropped sharply, and the unemployment rate has risen sharply.

(3). Reduction in informal and part-time employment: Many people lost their full-time jobs and had to take up part-time or informal temporary jobs to make ends meet. However, these employment opportunities were reduced during the pandemic, leaving more unemployment and economic hardship [5].

Figure 2: The unemployment rate in Amarican [6].

Note: The unemployment rate increased dramatically since 2020.

4.3. treasury rate

The United States Treasury market also experienced some turbulence and volatility in the early stages of the epidemic. In Figure 3. The global economic uncertainty and market turmoil, before the Government took some measures led to a significant increase in investor demand for safe-haven assets. U.S. Treasuries have always been considered one of the safest safe-haven assets in the world. As a result, investors turned to United States Treasuries in the early stages of the epidemic, driving up their prices and lowering their yields [7]. In summary, the United States had more serious fiscal deficits, high unemployment, and overpriced Treasuries in the pre-epidemic period.

Figure 3: The 10-year treasury rate in the U.S. from 1990 to 2020 [8].

Note: The U.S. treasury rate increased in 2020.

5. Measures

So the United States Government, under the pressure of its financing needs, decided to issue a large amount of Treasury bonds in the market to obtain the large amount of funds needed during the epidemic [9]. Before and during the pandemic, the U.S. government issued many treasury bonds to deal with the recession and support economic recovery. Below are some of the key moments in the issuance of treasury bonds:

(1) September 2019 to February 2020: In the period leading up to the outbreak, the U.S. government continues its previous Treasury bond issuance programme, issuing various types of Treasury bonds in domestic and foreign markets to fund government operations.

(2) March 2020 to December 2020: This was the period when the epidemic severely impacted the United States economy, and the United States Government was faced with fiscal deficits and the need to support economic recovery. Around this time, the United States issued many treasury bonds to raise funds to respond to the epidemic.

(3) March 2021 to present: against the backdrop of advancing US vaccination programmes and gradual economic recovery, the US government continues to issue treasury bonds to support economic recovery and public spending.

Therefore, it can be argued that between 2020 and 2021, before and after the outbreak, the US government issued many treasury bonds to stabilize the economy and support the outbreak response. During the epidemic, the United States Government and the Federal Reserve adopted many policies and measures to support the economy and financial markets. These included the purchase of large quantities of treasury bonds and government-backed bonds.

The Federal Reserve has adopted a policy of quantitative easing through the purchase of treasury bonds and other financial instruments to maintain the stability of financial markets, provide liquidity, and reduce long-term borrowing costs [10]. It should be noted that employment in the United States has improved as vaccination rates have increased and the economy has gradually recovered. Since the 2020 epidemic, the Federal Reserve has lowered its short-term benchmark interest rate to near zero and implemented an unprecedented bond-buying programme, buying nearly $6 trillion of US Treasury and mortgage bonds over two years. The Fed's bond-buying programme has included more than 580 U.S. Treasuries and 1,200 purchases of mortgage-backed securities. From March to October 2020, the Fed purchased at least $80 billion of U.S. Treasuries and $40 billion of mortgage-backed securities per month, initially to stabilize the financial markets and then later to hold down long-term interest rates [11].

6. Limitations and expectations

During the epidemic, the United States Government and the Federal Reserve purchased large quantities of treasury bills and bonds to provide financial support and economic stimulus. These measures increased the fiscal deficit. The U.S. Treasury Department data released on 16.10.2020 showed that affected by the substantial increase in fiscal spending, the U.S. fiscal deficit on 30 September 2020 reached a record $3.13 trillion, much higher than the $984.4 billion in the previous fiscal year. At the same time, U.S. fiscal revenues in fiscal year 2020 were about $3.42 trillion, slightly lower than the previous fiscal year's $3.462 trillion; fiscal expenditures were about $6.552 trillion, higher than the previous fiscal year's $4.447 trillion. The federal deficit in fiscal year 2020 accounted for a share of the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) of 15.2 percent, up from 4.6 percent in the previous fiscal year, the highest one during 1945 [12]. However, these measures are still considered necessary to respond to the epidemic and the economic crisis to stabilize financial markets, support economic recovery, and protect the public interest.

To cope with the depressed national economy under covid-19, the United States government decisively adopted various expansionary monetary and fiscal policies to achieve the purpose of stimulating the market. However, under many expansionary policies, the inflation rate, which was waiting to happen, also became the primary problem. Therefore, the Federal Reserve determined and maintained a low-interest rate as a hedge against the inflation risk, as suggested in Figure 4 [13]. The Federal Reserve cut interest rates by 150 basis points in an emergency, lowering the target federal funds rate to a historically low 0-0.25 percent, which has remained unchanged for 2 years. In addition, the Fed simultaneously lowered the legal reserve requirement rate, overnight reverse repo rate, and primary credit discount rate to 0.1%, 0%, and 0.25% respectively. To provide low-cost funds and liquidity support for all kinds of entities through direct interest rate control and to maintain the stability of the financial market [14].

Figure 4: The U.S. interest rate During the Covid-19 panic (2020-2022) [15].

Note: The chart depicts the Fed's interest rate settings in recent years, supporting the conclusion that the Fed had low-interest rates during the epidemic.

7. Conclusion

Under the epidemic crisis, the United States mitigated many negative impacts through monetary and fiscal policies. This paper shows that the United States, during the epidemic, faced fiscal deficits, high unemployment, and economic downward pressure through the issuance and purchase of treasury bonds to finance and stimulate the economy. Meanwhile, carefully controlled the potential risk of a high inflation rate. Consequently, deal with some of the difficulties during the epidemic. It shows that governments play an indispensable role in national economic development, and their macroeconomic policies often have the opportunity to ameliorate sudden economic crises.

References

[1]. Yamin, M. (2020) Counting the cost of COVID-19. International journal of information technology, 12(2), 311-317.

[2]. Tian, S.H. (2020) The impact of the epidemic on the US economy. People’s tribune, 17: 124-127

[3]. Deb, P., Furceri, D., Ostry, J. D., & Tawk, N. (2020) The economic effects of COVID-19 containment measures.

[4]. FRED Economic Research, Federal Surplus or Deficit. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FYFSD

[5]. Rate, L.F.P. (2013). Unemployment rate. Transportation, 48, 49.

[6]. U.S. BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS. (2020) Unemployment rate rises to record high 14.7 percent in April 2020. https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2020/unemployment-rate-rises-to-record-high-14-point-7-percent-in-april-2020.htm

[7]. Sarig, O., & Warga, A. (1989) Bond price data and bond market liquidity. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 24(3), 367-378.

[8]. Marcrotrends, 10 Year Treasury Rate - 54 Year Historical Chart. https://www.macrotrends.net/2016/10-year-treasury-bond-rate-yield-chart

[9]. Bell, S. (2000) Do taxes and bonds finance government spending?. Journal of economic issues, 34(3), 603-620.

[10]. Bernanke, B.S., Mihov, I. (1998) Measuring monetary policy. The quarterly journal of economics, 113(3), 869-902.

[11]. Ccpit Foreign Representative Office in the United States. (2020) The end of US pandemic stimulus: The Fed's biggest ever bond-buying spree is coming to an end. https://www.ccpit.org/usa/a/20220310/202203108gmz.html

[12]. Xinhuanet. (2020) The U.S. fiscal 2020 deficit hit a record high. http://www.xinhuanet.com/world/2020-10/17/c_1126622954.htm

[13]. Alvarez, F., Lucas Jr, R.E., Weber, W.E. (2001) Interest rates and inflation. American Economic Review, 91(2), 219-225.

[14]. Lv, H.M., Zhao, X.Q. (2021) Ultra-loose Monetary Policy and Extreme Polarization of rich and poor-Analysis and enlightenment based on the United States. Bank of China Macroscopic Observation, 384: 2.

[15]. FEDERAL RESEARCH. (2022) TRADINGECONOMICS.COM

Cite this article

Zhu,J.;Zhang,Z.;Wu,W. (2024). The Impact of Policy Uncertainty on the US Treasury Bond Market. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,89,120-125.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Financial Technology and Business Analysis

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Yamin, M. (2020) Counting the cost of COVID-19. International journal of information technology, 12(2), 311-317.

[2]. Tian, S.H. (2020) The impact of the epidemic on the US economy. People’s tribune, 17: 124-127

[3]. Deb, P., Furceri, D., Ostry, J. D., & Tawk, N. (2020) The economic effects of COVID-19 containment measures.

[4]. FRED Economic Research, Federal Surplus or Deficit. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FYFSD

[5]. Rate, L.F.P. (2013). Unemployment rate. Transportation, 48, 49.

[6]. U.S. BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS. (2020) Unemployment rate rises to record high 14.7 percent in April 2020. https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2020/unemployment-rate-rises-to-record-high-14-point-7-percent-in-april-2020.htm

[7]. Sarig, O., & Warga, A. (1989) Bond price data and bond market liquidity. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 24(3), 367-378.

[8]. Marcrotrends, 10 Year Treasury Rate - 54 Year Historical Chart. https://www.macrotrends.net/2016/10-year-treasury-bond-rate-yield-chart

[9]. Bell, S. (2000) Do taxes and bonds finance government spending?. Journal of economic issues, 34(3), 603-620.

[10]. Bernanke, B.S., Mihov, I. (1998) Measuring monetary policy. The quarterly journal of economics, 113(3), 869-902.

[11]. Ccpit Foreign Representative Office in the United States. (2020) The end of US pandemic stimulus: The Fed's biggest ever bond-buying spree is coming to an end. https://www.ccpit.org/usa/a/20220310/202203108gmz.html

[12]. Xinhuanet. (2020) The U.S. fiscal 2020 deficit hit a record high. http://www.xinhuanet.com/world/2020-10/17/c_1126622954.htm

[13]. Alvarez, F., Lucas Jr, R.E., Weber, W.E. (2001) Interest rates and inflation. American Economic Review, 91(2), 219-225.

[14]. Lv, H.M., Zhao, X.Q. (2021) Ultra-loose Monetary Policy and Extreme Polarization of rich and poor-Analysis and enlightenment based on the United States. Bank of China Macroscopic Observation, 384: 2.

[15]. FEDERAL RESEARCH. (2022) TRADINGECONOMICS.COM