1. Introduction

The increasingly exacerbated phenomenon of inequality can potentially result in the breakdown of a nation's economic framework and political unrest. Policies and institutions designed to reassign wealth from the affluent to the less privileged could face erosion, paradoxically consolidating more wealth and power among the affluent and consequently undermining the purchasing capacity of those with lower incomes. Furthermore, deliberate government policies also constitute one of the factors driving the escalation of inequality, leading to a decline in people's trust in democratic governmental systems. To tackle the problem of inequality, John contends that tax reform could be a viable strategy. He suggests that implementing measures such as the Buffet Rule and wealth taxes could prove effective in mitigating inequality [1]. Nevertheless, our investigation reveals certain indications, as pointed out by Oguzhan Akgun, Boris Cournède and Jean-Marc Fournier [2], Florian Scheuer, and Joel Slemrod [3], that have the potential to challenge the validity of the two approaches proposed in John's paper.

2. The current condition of Australia

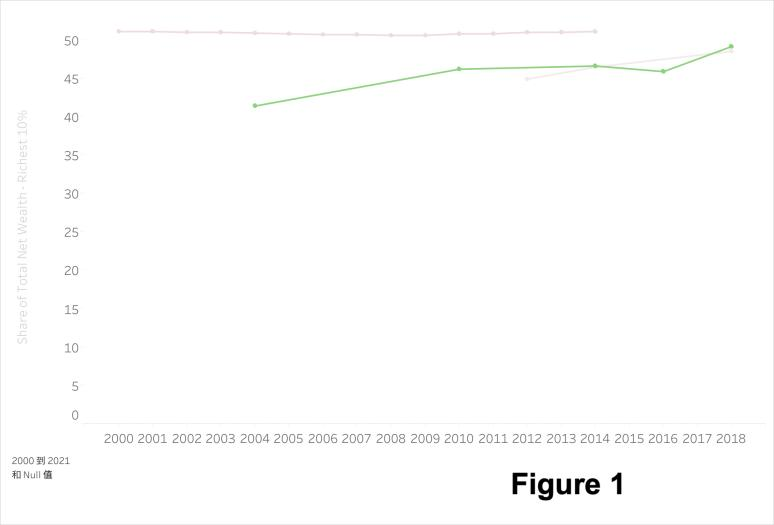

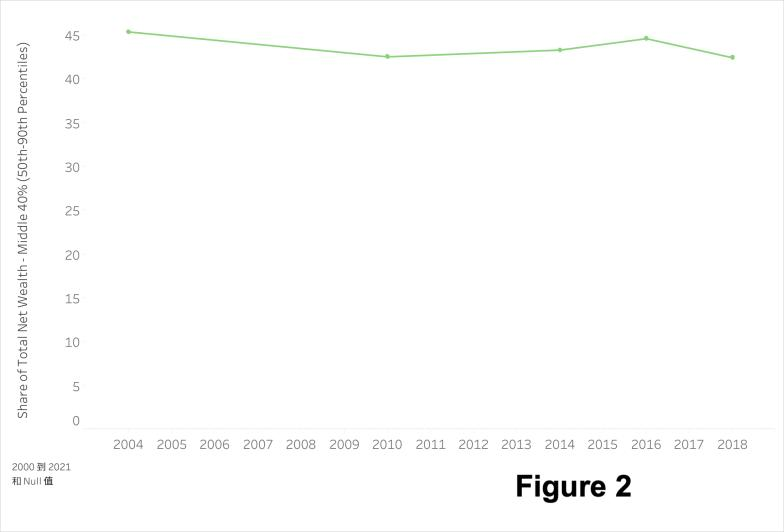

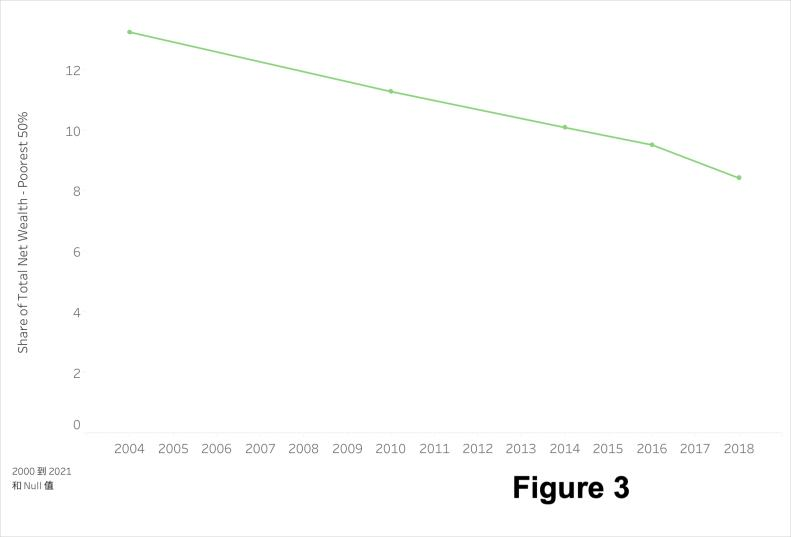

Australia's income tax structure has shifted towards being less inclined towards progressivity over time. This alteration has led to a reduction in tax rates, implying that individuals with higher incomes are not required to pay proportionately higher taxes. Furthermore, the establishment of tax expenditures tends to advantage and provide gains to those situated within the more affluent and prosperous segments of society [1]. While there has been an increase in income inequality in Australia, the majority of wealth is still held by individuals at the highest economic echelons. Based on the data examined by The GC Wealth Project, with the reference year set as 2016, it can be observed that the top 10% wealthiest individuals possess 45% of the total wealth. Simultaneously, the middle class, constituting 40% of all households, holds an equivalent 45% share of the total wealth. Conversely, the poorest 50% of households collectively own a mere 10% of the total wealth.

Figure 1: The share of total net wealth held by the top ten percent of people in Australia. [4]

Figure 2: The share of total net wealth held by the middle forty percent of people in Australia. [4]

Figure 3: The share of total net wealth held by the bottom fifty percent of people in Australia. [4]

Note: Based on the analysis conducted using the Luxembourg Wealth Study Database (represented by the green line), using 2016 as the reference year, figure 1 illustrates that the top 10% of individuals possess 45% of the total wealth. Similarly, figure 2 indicates that the middle 40% of households also hold a 45% share of the total wealth. On the contrary, figure 3 reveals that the bottom 50% of citizens have access to only 10% of the total wealth.

Sheil and Stilwell contend that the growing inequality is exacerbating two divisions within the societal framework. According to their perspective: The wealthy upper class, particularly the Top 10% and Top 1%, is experiencing a continuous increase in their wealth. This increase is occurring not only in comparison to lower-income households but notably in contrast to the following middle-income citizens. This disparity is leading to the expansion of two divisions: one between the poorest and the middle-income population, and another between the richest 10% and the middle people [1]. Not only do Sheil and Stilwell articulate their viewpoints, but a multitude of experts have also voiced apprehensions regarding the escalating divergence in income and wealth. This phenomenon poses risks to social equilibrium, economic functionality, and even the democratic fabric [1].

3. Solution

John discusses the importance of implementing tax reform as a means to address the issue of inequality. The primary objectives of this tax reform revolve around enhancing the progressiveness of the existing tax system. This involves ensuring that individuals with higher incomes contribute a larger proportion of taxes and rectifying any preferential tax expenditures that currently benefit wealthier individuals. Additionally, the reform aims to abolish the constraints on taxing resource rents [1]. John's proposed reform is divided into two key facets: the introduction of the Buffet Rule for both individuals and corporations, and the implementation of wealth taxes.

3.1. Buffet Rule for individuals

Warren Buffet experienced astonishment when he realized that his average tax rate was lower than that of his secretary, despite his income and wealth are higher [5]. This phenomenon occurred due to the utilization of various tax expenditures, such as business deductions, exemptions, offsets, concessional taxation of some activities and deferral of liability. These measures collectively lowered his taxable income [1]. However, this situation is widely regarded as unjust within society. Consequently, it is believed that each buck should be subject to equal taxation, regardless of the earner's identity.

The essence of the Buffet Rule lies in its endeavor to counterbalance these tax expenditures by imposing a tax liability based on gross income rather than taxable income [1]. Notably, President Obama introduced the Buffet Rule as a fundamental principle of tax fairness, stipulating that no millionaire should pay less than 30% of their income in taxes [5]. Similarly, in Australia, the Greens discovered instances where high-income earners exploited tax expenditures, resulting in no income tax being paid. In response, the Greens proposed the Buffet Rule to recoup 35% of their $129 million gross revenue, equivalent to $45.15 million [6].

In summary, the Buffet Rule stands apart from conventional tax principles as it effectively addresses the issue of tax expenditures. In other words, it prevents the reduction of owed taxes through offsets. Even if these offsets are legally employed, the Buffet Rule acknowledges that substantial gross revenue requires a certain societal contribution, considering that such revenue generation is facilitated by society. Furthermore, individuals earning $300,000 or more annually are deemed to have the financial capacity to contribute, even if they possess non-taxable or minimally taxed status for that particular income year [1].

3.2. Buffet Rule for companies

As per the details outlined in the Corporate Tax Transparency Report for the 2014-15 Income Year, which was published by the Commissioner of Taxation, it reveals that during the specified period, 36% of the 1904 public companies, each with a turnover ranging between $100 million and $200 million, managed to evade paying any income tax [7]. This circumstance is attributed to the utilization of tax expenditures and the practice of tax avoidance. Much like the impact of the Buffet Rule on individuals, a similar effect can be achieved for corporations by curbing both tax expenditures and tax avoidance practices [1].

3.3. Wealth Taxes

Thomas Piketty advocates for the implementation of a progressive global tax on capital(regarded as assets) coupled with enhanced financial transparency [8]. He asserts that the growing disparity in income and wealth poses a dual threat to both economic growth and democratic principles [7], [9]. Piketty perceives a global wealth tax as a means to counterbalance the escalating concentration of wealth and as a catalyst to promote greater fiscal openness and transparency [8]. In specific terms, Piketty proposes a tax structure involving a 0% tax rate for net assets below 1 million euros, a 1% rate for assets between 1 million euros and 5 million euros, and a 2% rate for amounts exceeding that range [8]. Additionally, he suggests contemplating considerably higher rates, potentially around 5% or 10%, for ultra-wealthy individuals possessing assets surpassing 1 billion euros [8].

One of the rationales Piketty presents in favor of net wealth taxes is that, apart from aiding in the restoration of democracy and citizen engagement through redistributive policies, wealth serves as a more accurate indicator of an individual's ability to contribute than income alone [8]. Moreover, the introduction of net wealth taxes is expected to incentivize increased investment in assets capable of generating substantial income returns to cover the tax obligations [8]. Furthermore, the viability of a global wealth tax hinges on an environment of fiscal transparency. Such transparency would dispel the opacity surrounding wealth ownership, fostering a more rational discourse about critical issues like the welfare state, climate change mitigation, and global poverty [8].

4. Contradictions

4.1. Rebuttals to the Buffet Rule for individuals

The Buffet Rule is designed to eliminate tax benefits that primarily favor the wealthiest individuals, thereby increasing the tax obligations of the richest individuals. Simultaneously, this results in a higher tax burden for those with substantial wealth. As tax burdens rise, research by Oguzhan, Boris, and Jean-Marc reveals that the richest individuals may get lower marginal utility from additional income, potentially leading them to supply less labor in response to higher taxation [2]. The consequence of this situation is that greater progressivity in the top half of the distribution that results from an increase in the labour tax wedge on above average incomes entails lower long-term output levels [2]. To sum up, the implementation of a more progressive tax system is expected to result in lower long-term output levels. This condition may pose a threat to the national growth.

4.2. Rebuttals to the wealth taxes

Over the past thirty years, numerous European countries have utilized wealth taxes, yet currently, only a quarter of nations continue to employ them. Florian and Joel conducted research to elucidate why the majority, constituting three-quarters of these countries, chose to abandon this approach. According to a 2018 report from the OECD, various concerns were listed as explanations: efficiency costs, risk of capital flight, failure to meet redistributive goals, and high administrative costs [3]. For instance, in Germany, the Federal Constitutional Court declared the wealth tax unconstitutional in 1995 due to its differentiation between property and financial assets, which was considered a violation of the tax equality principle (Drometer et al. 2018) [3]. Similarly, in Sweden, the wealth tax was critiqued for its treatment of business equity, resulting in regressivity —taxing middle-class wealth like housing and financial assets, while exempting substantial assets of the wealthiest individuals, such as closely held firms. This was attributed to fostering tax evasion and avoidance, even prompting capital flight to tax havens (Waldenström 2018) [3].

However, there are instances where wealth taxes have been successfully implemented, as seen in Switzerland. The broader Swiss tax framework contributes to the prominence of the wealth tax there. Firstly, no capital gains tax is imposed on movable assets (like company stocks) unless the owner is engaged in professional securities trading [3]. Secondly, most cantons have eliminated taxes on gifts and inheritances from parents to children. Consequently, the Swiss wealth tax serves as a substitute, at least in part, for capital gains and estate taxes prevalent in other nations [3]. Thirdly, the concept of bank secrecy in Switzerland prevents third-party reporting of financial assets, which hampers enforcement [3]. Lastly, although there are some guidelines for valuing privately held business assets, relying on a weighted average of recent capitalized earnings and net asset holdings, significant discretion remains with cantonal tax authorities. This latitude may contribute to a situation where the affluent receive relatively lenient treatment [3].

5. Conclusion

Both the Buffet Rule and wealth taxes are intended to address inequality; however, their effectiveness is hampered by the expanding influence of the increasingly free market, which in turn exacerbates the inequality [1]. Moreover, flaws in these two approaches pose risks to a nation's growth and progress. In my view, the challenges faced by each approach are distinct. For instance, a plausible solution could involve government intervention by creating opportunities for the unemployed or low-income individuals to engage in the production of essential daily goods at comparatively modest wages. This approach would potentially lead to enhance long-term productivity and a simultaneous reduction in inequality. Furthermore, the viability of wealth taxes is contingent on specific tax frameworks, such as the broad Swiss tax system. Hence, it becomes imperative for each country to meticulously choose tax methodologies or alternative strategies that align with its unique characteristics.

References

[1]. Passant, J. (2017). Tax, Inequality and Challenges for the Future. In R. LEVY, M. O’BRIEN, S. RICE, P. RIDGE, & M. THORNTON (Eds.), New Directions for Law in Australia: Essays in Contemporary Law Reform (pp. 49–58). ANU Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1ws7wbh.8

[2]. Akgun, O., B. Cournède and J. Fournier (2017), "The effects of the tax mix on inequality and growth", OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1447, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c57eaa14-en.

[3]. Scheuer, F., & Slemrod, J. (2021). Taxing Our Wealth. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 35(1), 207–230. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27008021

[4]. The Luxembourg Wealth Study Database

[5]. The National Economic Council, The Buffett Rule: A Basic Principle of Tax Fairness (Washington, April 2012), obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2012/04/10/white-house-report buffett-rule-basic-principle-tax-fairness (viewed 2 May 2016).

[6]. The Greens, ‘Buffett Rule: A High-Income Tax Guarantee’, greens.org.au/buffett-rule (viewed 3 May 2016); Katherine Murphy, ‘Labor Faces Internal Wrangle Over “Buffett rule” to Stop Wealthy Avoiding Tax’ , The Guardian Australia 4 April 2017, www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2017/apr/04/labor-faces-internal-wrangle-over-buffett-rule-to-stop-wealthy-avoiding-tax (viewed 6 April 2017).

[7]. Australian Taxation Office, Corporate Tax Transparency Report for the 2014– 15 Income Year (Canberra, 2017), www.ato.gov.au/business/large-business/in-detail/tax-transparency/corporatetax-trans parency-report-for-the-2014-15-income-year/?page=5#Net_losses_and_nil_tax_payable (viewed 6 April 2017).

[8]. Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century (The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2014).

[9]. Bob Douglas, Sharon Friel, Richard Denniss and David Morawetz, Advance Australia Fair? What to Do About Growing Inequality in Australia (Australia21, 2014) 17, gallery. mailchimp.com/d2331cf87fedd353f6dada8de/files/1b2c7f48-928f-4298-81db-cf053a22 4320.pdf (viewed 3 May 2016).

Cite this article

Zhang,D. (2024). Debate on Addressing Income and Wealth Inequality among the Australian People. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,97,89-94.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Financial Technology and Business Analysis

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Passant, J. (2017). Tax, Inequality and Challenges for the Future. In R. LEVY, M. O’BRIEN, S. RICE, P. RIDGE, & M. THORNTON (Eds.), New Directions for Law in Australia: Essays in Contemporary Law Reform (pp. 49–58). ANU Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1ws7wbh.8

[2]. Akgun, O., B. Cournède and J. Fournier (2017), "The effects of the tax mix on inequality and growth", OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1447, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c57eaa14-en.

[3]. Scheuer, F., & Slemrod, J. (2021). Taxing Our Wealth. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 35(1), 207–230. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27008021

[4]. The Luxembourg Wealth Study Database

[5]. The National Economic Council, The Buffett Rule: A Basic Principle of Tax Fairness (Washington, April 2012), obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2012/04/10/white-house-report buffett-rule-basic-principle-tax-fairness (viewed 2 May 2016).

[6]. The Greens, ‘Buffett Rule: A High-Income Tax Guarantee’, greens.org.au/buffett-rule (viewed 3 May 2016); Katherine Murphy, ‘Labor Faces Internal Wrangle Over “Buffett rule” to Stop Wealthy Avoiding Tax’ , The Guardian Australia 4 April 2017, www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2017/apr/04/labor-faces-internal-wrangle-over-buffett-rule-to-stop-wealthy-avoiding-tax (viewed 6 April 2017).

[7]. Australian Taxation Office, Corporate Tax Transparency Report for the 2014– 15 Income Year (Canberra, 2017), www.ato.gov.au/business/large-business/in-detail/tax-transparency/corporatetax-trans parency-report-for-the-2014-15-income-year/?page=5#Net_losses_and_nil_tax_payable (viewed 6 April 2017).

[8]. Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century (The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2014).

[9]. Bob Douglas, Sharon Friel, Richard Denniss and David Morawetz, Advance Australia Fair? What to Do About Growing Inequality in Australia (Australia21, 2014) 17, gallery. mailchimp.com/d2331cf87fedd353f6dada8de/files/1b2c7f48-928f-4298-81db-cf053a22 4320.pdf (viewed 3 May 2016).