1. Introduction

Celebrity endorsement is a common strategy which can better simulate customers’ willingness to purchase in brand marketing [1]. Some fans purchase endorsed products mainly to obtain favorite products and support celebrities [2]. Brands use celebrity endorsements because most people believe that the products endorsed by celebrities are guaranteed and have low risks [3]. Official online stores such as Taobao will launch special activities during celebrity endorsements, such as pre-listing products and providing celerity-related gifts. Fans’ comments in products comment sections on online stores can be easily find their purchase motivation. But offline stores will be difficult to directly understand purchase motivations. This article explores the application of behavioral economics in celebrity endorsements and verifies the relevant conclusions through online surveys.

2. Behavioral Economics Related to this Study

In the marketing strategy of celebrity endorsements, in addition to the halo effect, representative bias and framing effect are also widely used.

The halo effect is a cognitive bias that causes people to see another person’s qualities in a way that matches their past impressions of other characteristics [4]. Consumers may become potential or actual customers by following a celebrity’s endorsed brand. Brands can use this effect to promote sales, but scandals about celebrities may also have a negative impact on the brand.

The phenomenon in which a smaller group of people or items properly represents a larger group so that the smaller group serves as a representative example of the larger group [5]. Because of their positive emotions towards celebrities, fans will be more inclined to purchase products endorsed by celebrities and is also one of the reasons why brands choose celebrity endorsements.

Framing effects involve people using their primary framework, to frame what goes on in their environment from different sources [6]. When celebrities endorse a certain brand, many merchants will emphasize that if customers don’t purchase products during the first launched period, they will lose some celebrity derivatives or specific co-branded products. In fact, customers only gained more derivative products in first launched period. Many fans don’t want to lose those derivatives, and they will immediately place orders during the new discount period.

3. Methodology

Pandora is a Danish jewelry brand with hundreds of stores in China and can be purchased through various online channels. In recent years, Pandora has chosen some young celebrities to endorse their products. Influenced by the celebrity’s halo, the endorsers styles will sell well. By browsing the comments of the celebrity endorser’s styles, people can fund some buyers who purchased Pandora because of endorsers. However, two previously reputable endorsers for Pandora have some scandals, which has also affected Pandora’s reputation. Based on the above situation, to prevent the negative impact of celebrities who have already exposed scandals on the subjects from causing some deviations in the results, the experiment will simulate a celebrity X aged 25-30. Besides that, X has previously appeared in numerous TV series but is not well-known and doesn’t have any commercial endorsements. Based on previous news and gossip, the celebrity has hardly any negative news. Later on, X released significant scandals. Therefore, the brand is terminated.

3.1. Research Hypothesis

Celebrity endorsements usually bring positive effects to both the celebrities and brands, but celebrity scandals may negatively affect brands. In addition, the experiment suggests that gender, age, education level, willingness to purchase endorsed products, and attention level to celebrities all affect the potential customers attitudes and their further purchase decisions toward brands.

Therefore, this article proposes the following hypothesis. Hypothesis 1: Negative news has a greater impact on brands endorsed by celebrity endorsers with mixed reviews. Potential customers have lower support and purchase intentions for the brand, and if they don’t support brands, their emotional reactions are stronger. On the contrary, if brands choose endorsers with good reputations, even if customers don’t support the brand when the endorser is exposed to scandals, they will not have strong negative emotions. Hypothesis 2: Women are more susceptible to scandals involving celebrity endorsers than men, and if they hold negative attitudes towards brands, their emotions will be stronger. Moreover, the probability of women continuing to be unwilling to purchase the brand in the future will be higher. Hypothesis 3: Age will affect the final attitude and purchase intention towards the brand. The younger the age, the greater the impact of celebrity scandals, and the lower the probability to continually support the brand and purchase products (H3a). Similarly, the probability to not support the brand and not purchase will decrease (H3b). Hypothesis 4: Participants with higher education levels are more likely to have a positive attitude towards the brand when they receive celebrity scandals and terminations (H4a). Similarly, the probability of continually to purchase products from this brand will be higher (H4b). Hypothesis 5: Participants who have a higher willingness to purchase products endorsed by celebrities are more likely to have negative perceptions of the brand when they know the celebrity’s scandals and termination information (H5a). Similarly, they are even less willing to purchase products from this brand. Hypothesis 6: The lower the attention level to the celebrity’s activities, the lower the probability of holding positive attitudes toward the brand after receiving celebrity’s scandals and brand termination (H6a). Similarly, the probability of purchase intentions will be lower in the future (H6b).

3.2. Research Design

Based on these hypotheses, this study divided the participants into two groups to investigate the impact of framing effects under celebrity halo on customers. The first group has 46% males, and the second group has 40%. The first group of participants will receive information about celebrities in the questionnaire: good reputation first, bad reputation later. The second group of participants will receive information: the celebrity’s reputation is mixed. However, other celebrities’ characteristics are consistent. Participants in two groups had the same questions in the questionnaire.

The questionnaire consists of 11 questions, with the first three questions aimed at demographic questions: gender, age, and education level. The purpose of the fourth and fifth questions is to obtain the participants’ attention to celebrities and their willingness to purchase endorsed products. The sixth and seventh questions are about purchasing motivation and what kind of promotional activities customers hope to receive during celebrity endorsements. The eighth to eleventh questions ask about the participants’ views on the brand and their willingness to purchase the brand’s products after the celebrity generates negative news and the brand terminates the contract.

3.3. Data Collections and Data Processing

Based on the above assumptions, the experiment collected 106 questionnaires with 100 valid for two weeks through online surveys. For hypothesis testing, this study used cross analysis method which takes gender, age, education level, attention level to celebrities, and willingness to purchase celebrity endorsed product as independent variables, and their attitudes toward the brand and whether they purchase products after the celebrity endorser is terminated as dependent variables.

Based on the above data, cross analysis is used in hypothesis test section. Gender, age, education level, willingness to purchase celebrity endorsed products, and celebrity attention were analyzed separately to participants’ attitudes towards the brand and subsequent hospital purchases after the endorser’s scandals. Finally, based on the variables in these hypotheses the experiment used R language to fit regression models to test the impact of different factors on purchase intention.

4. Results

The participants are relatively young, with 65% aged 18 to 25. The participants generally have a high level of education: over 90% are bachelor’s degree or higher. 48% of participants in group 1 only buy endorsed products that they like and are participants, while 38% buy products that they can pay for and like. In group 2, these two proportions are 42% each. In terms of celebrity attention level, minority participants fully focused on celebrity activities. 24% of participants in the first group and 16% in the second group pay attention to 50% of celebrity’s activities, and most participants only focus on high-quality programs. In terms of purchase motivation, 65% of the participants purchased celebrity endorsed products because they were recommended by celebrities and liked the products. In the promotion of new endorsements products, the first group values discounts and discounts plus celebrity derivatives the most, while the second group values discount plus celebrity derivatives and special derivatives during the endorsement period the most.

4.1. Hypothesis Test

H1:

According to the data, 40% of the participants in group 1 stated that the brand’s responsibility was little after the celebrity had problems. The proportion of participants who had same thought in group 2 is 38%. 8% in group 1 and 10% in group 2 believe that the brand is responsible, but the main issue is caused by celebrities. Similarly, 8% in group 1 believe that both the brand and the celebrity have a significant responsibility. However, among the participants in group 2, while 10% believe that the responsibility of both brand owners and celebrities is equally significant. According to this situation, when celebrities who have mixed reviews had scandals during their endorsement period, the proportion of participants who believe that the brand’s responsibility is little will decrease, while the participants who believe that the brand’s responsibility is greater will increase.

When asked future purchase, 26% of participants in group 1 were willing to purchase, while 60% held a neutral attitude. In group 2, 22% of participants are willing to purchase. Both groups have 14% of the participants expressed reluctance to purchase products. However, 2% of the participants in group 2 expressed strong reluctance. According to this situation, when the endorsers’ reputation is already mixed, the number of people who are willing to continually purchase the brand will decrease when endorsers are exposed to scandals during their endorsement period and terminated by brands. The rate of unwillingness to purchase the brand remains unchanged, but the rate of strong unwillingness to purchase has increased. Overall, H1 has been accepted.

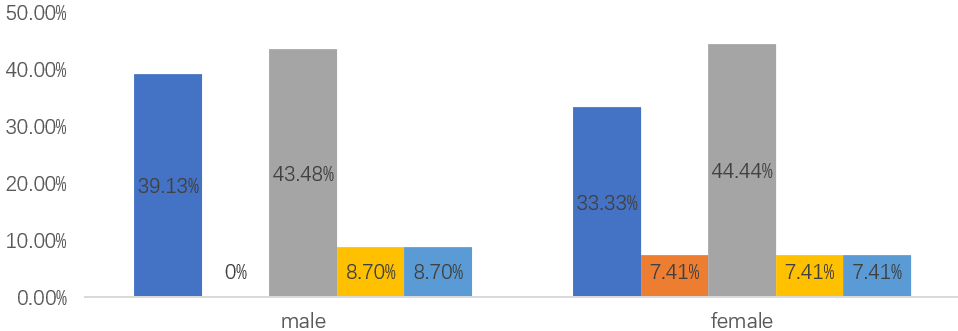

4.1.1. Gender

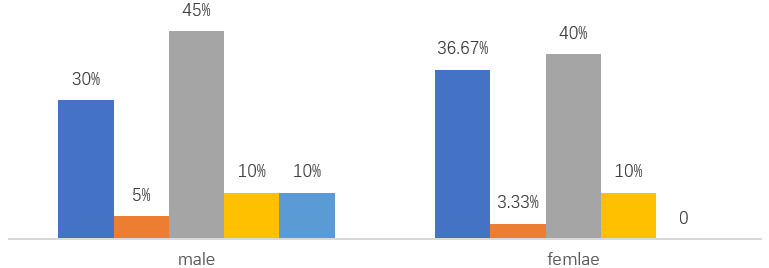

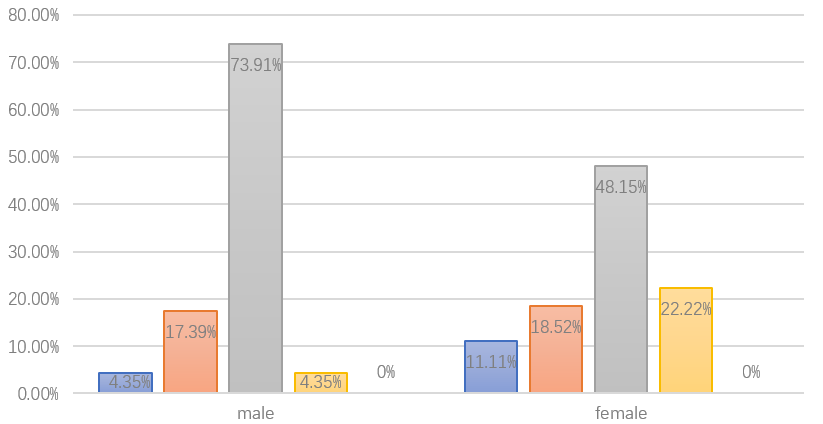

According to Figure 1 and Figure 2, in both survey groups, when celebrity X had scandals, most participants believed that the brand had little responsibility. Female participants’ attitudes towards the brand are more influenced, especially in group 1. Similarly, the proportion of female participants unwilling to purchase the brand is much higher than that of male participants. In group 2, male and female participants showed a more consistent view of brand responsibility, but female participants still showed a stronger unwillingness to purchase. After the celebrity scandal, about 30% of female participants in group 1 were still willing to support the brand, while in group 2, this proportion decreased to 16.67%.

Figure 1: Different genders' attitudes towards brand when celebrity endorser is exposed to scandals in Group 1.

Figure 2: Different genders' attitudes towards brand when celebrity endorser is exposed to scandals in Group 2.

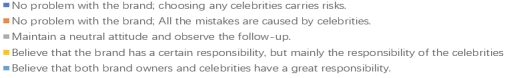

Moreover, comparing data based on Figure 3 and Figure 4, it can be concluded that if a celebrity has a good reputation before, the probability of participants who support the brand after the celebrity’s endorser is exposed to a scandal during the endorsement period is higher than the group that didn’t say that the celebrity had a good reputation before. And the participants who didn’t support the brand were also lower than another group. Even if the participants are unwilling to purchase the brand’ products in the future, the emotion of unwillingness to purchase is not very strong.

Figure 3: Whether different genders willing to purchase products of this brand after scandals involving brand endorser in Group 1.

Figure 4: Whether different genders willing to purchase products of this brand after scandals involving brand endorser in Group 2.

Based on the above analysis, it can be found that more women than men are unwilling to support a brand or even more unwilling to purchase its products after hearing about celebrity scandals. Therefore, H2 can be accepted.

4.1.2. Age

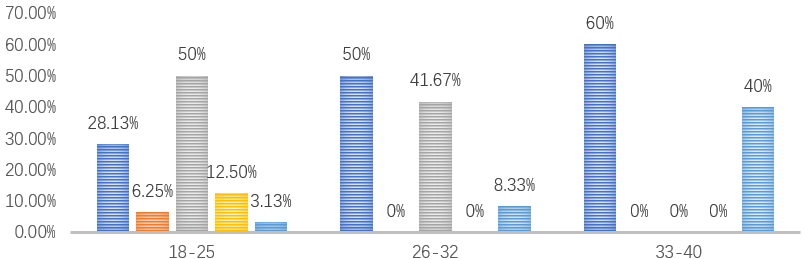

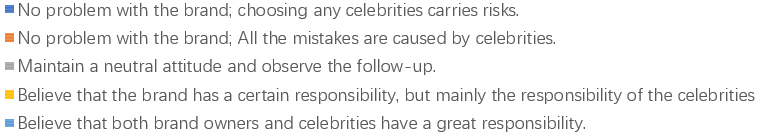

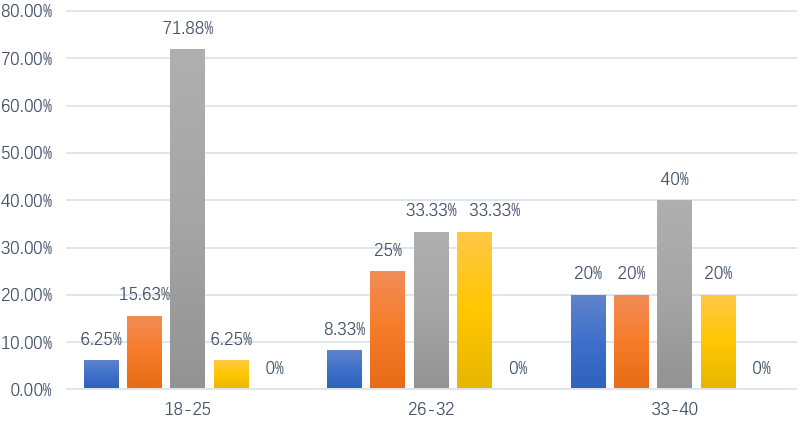

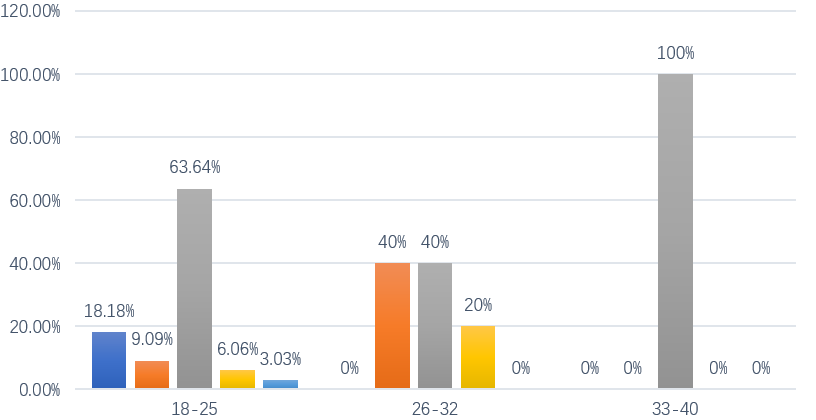

According to Figure 5, in group 1, as the age increases, the proportion of participants who believe that the brand’s responsibility is relatively small gradually increases in each age group after learning about the celebrity’s scandal and termination. For example, among the participants aged 18-25, 34.38% believed that the brand’s responsibility was relatively small, while 60% of participants aged 33-44 had same thoughts. In group 2, according to Figure 6, same trend will appear as group 1. For example, among the participants in this group aged 18-25, 36.36% believe that the brand’s responsibility is relatively small, while 66.67% of participants aged 33 to 40 had same thought.

Figure 5: Attitudes towards the brand after scandals involving brand endorser of different ages in Group 1.

Figure 6: Attitudes towards the brand after scandals involving brand endorser of different ages in Group 2.

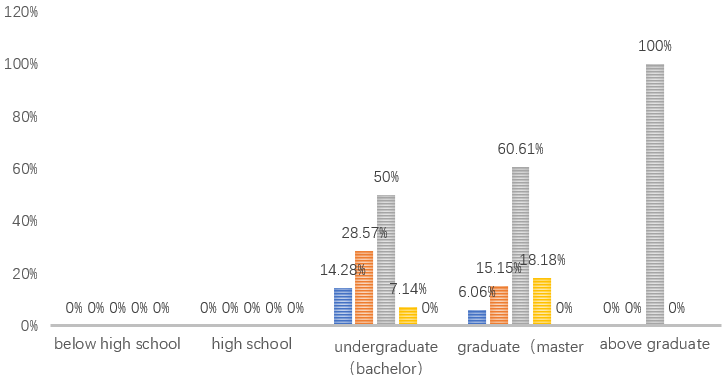

According to Figure 7, in group 1, when asked about purchase intention, 40% of participants aged 33 to 40 were willing to continually purchase the brand’s products, while the proportion of participants aged 18 to 25 was 21.88%. Among the participants who were unwilling to purchase the brand, the ratio was not distributed by age. For example, 20% of participants aged 33 to 40 believe that the responsibility of the brand is significant. The ratio for participants aged 26 to 32 is 33.33%. The ratio for participants aged 18 to 25 is 6.25%. Similarly, in group 2, according to Figure 8, when asked about purchase intention, the probability of participants willing to purchase the brand’s products increases with age in each age group. For example, 27.27% of participants aged 18 to 25 are willing to continually purchase products from the brand, and 100% of participants aged 33 to 40 are willing to continually purchase products from the brand. However, among participants who held a negative attitude towards the brand, the rate change was not related to age.

Figure 7: Whether participants of different ages are willing to purchase products from the brand has been affected by the scandal involving the brand endorser in Group 1.

Figure 8: Whether participants of different ages are willing to purchase products from the brand has been affected by the scandal involving the brand endorser in Group 2.

Based on the above data, age affects participants’ perception of the brand and their further purchase after learning about celebrity scandals and termination news. However, this hypothesis can only be partially supported. The probability of participants who have a negative attitude towards the brand and are unwilling to purchase products doesn’t follow a regular pattern across different age groups. In this way, we cannot support H3b. Hypothesis 3 can only be partially supported.

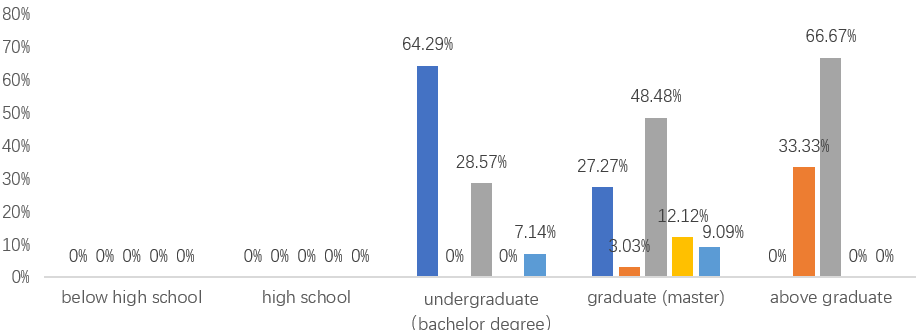

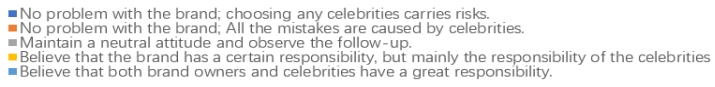

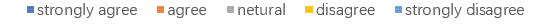

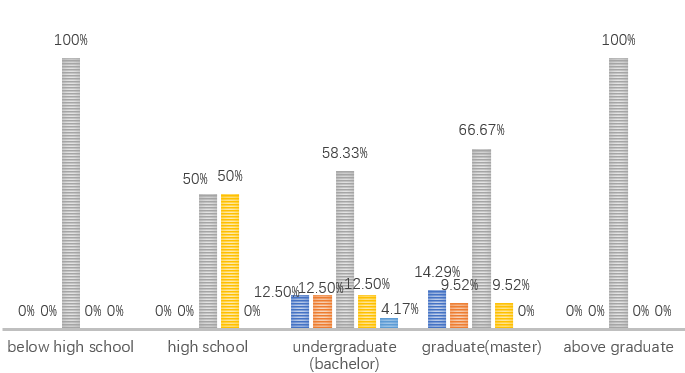

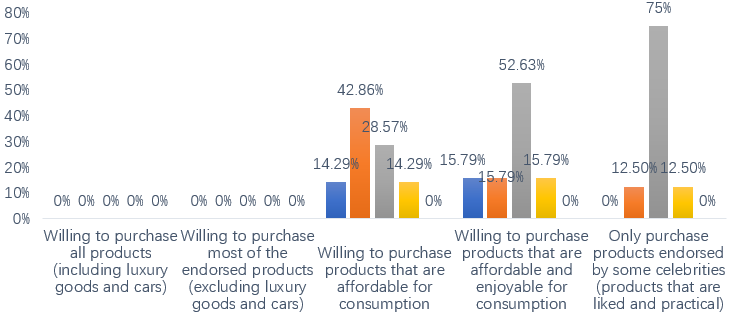

4.1.3. Education

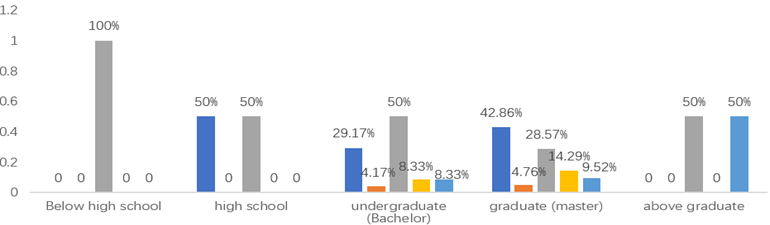

According to Figure 9, in group 1, no participants with high school education or below were in this group. The higher the education level of the participants, the lower the proportion of those who believe that the brand has little responsibility after receiving news of celebrity scandals and brand termination, but the proportion of those who maintain a neutral attitude increases. Similarly, in group 2, according to Figure 10, same trend will be appeared as group 1. For example, 50% of participants with a high school education are willing to support the brand, while among participants with a bachelor's or college education, this ratio is only 33.74%. However, among the participants with a master's degree, 47.62% are willing to support the brand.

Figure 9: Participants with different educational backgrounds' attitudes towards the brand after scandals involving brand endorsers in group 1.

Figure 10: Participants with different educational backgrounds' attitudes towards the brand after scandals involving brand endorsers in group 2.

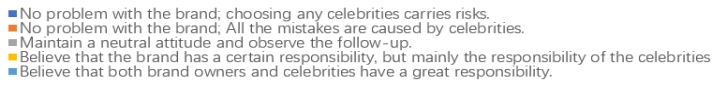

According to Figure 11, in group 1, overall, the higher the education level, the more neutral the perception of brand responsibility, and the lower the willingness to purchase. Participants with a bachelor's have the highest willingness to purchase, while those with a higher degree than a master's degree have the highest proportion of neutral attitudes. With the improvement of education, the proportion of people who are unwilling to purchase has also increased, but the emotions are not strong. In group 2, according to Figure 12, those with lower education than high school and higher education than master's are 100% neutral attitude to further purchase. When asked future purchase intention, the proportion of willingness decreases when education level increases.

Figure 11: When a brand endorser is exposed to scandals, whether participants with different educational backgrounds are willing to purchase the brand's products in Group 1.(Left)

Figure 12: When a brand endorser is exposed to scandals, whether participants with different educational backgrounds are willing to purchase the brand's products in Group 2.

Based on the above data, Hypothesis 4 should be rejected. After learning about celebrity scandals and termination news, the proportion of participants who hold a neutral attitude towards the brand will increase with their education level. However, according to two sets of data, as their education level increases, their willingness to purchase will actually decrease.

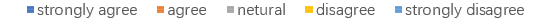

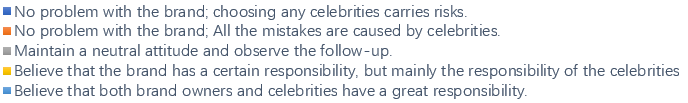

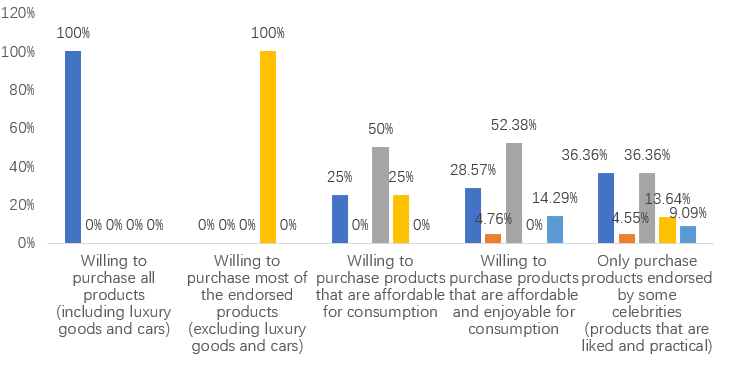

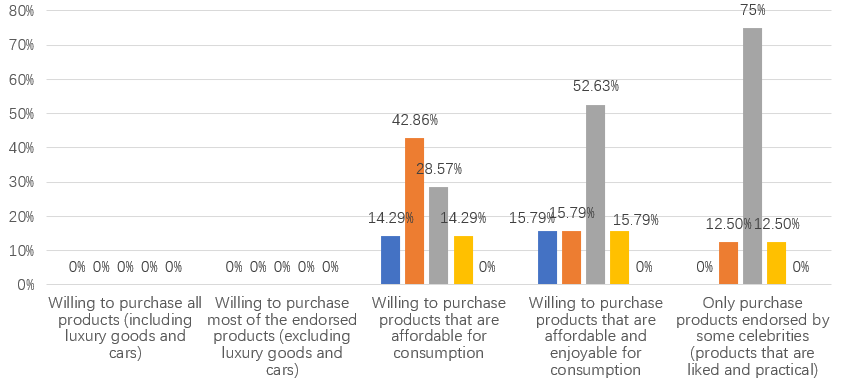

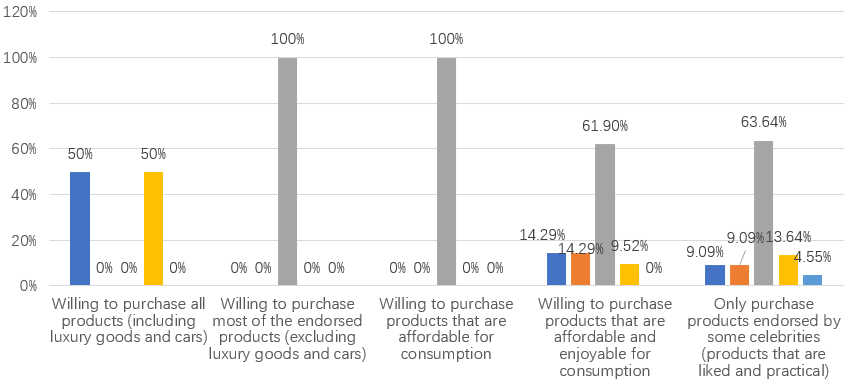

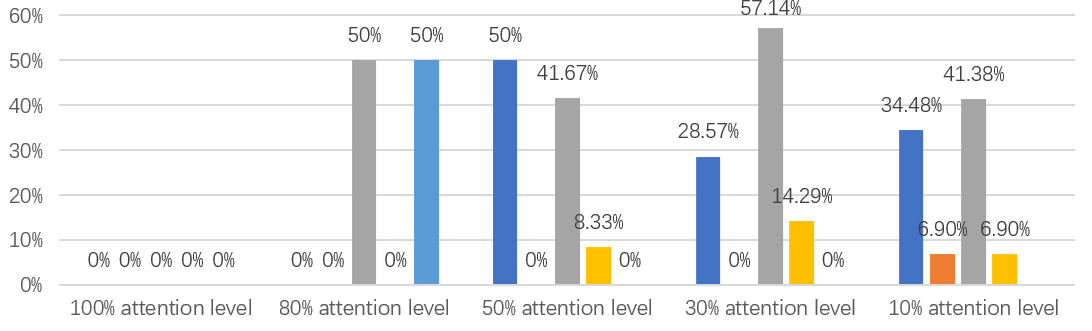

4.1.4. Endorsed Product‘s Purchasing Category

According to Figure 13 and Figure 15 in group 1, participants generally think that brands have no responsibility or neutral attitudes after celebrities are exposed to scandals and terminate their contracts. The willingness to purchase is closely related to the category of endorsed products they are willing to purchase. Participants who choose affordable products have the highest willingness to purchase, while those who choose products with high practicality have a relatively lower willingness to purchase.

According to Figure 14 and Figure 16, group 2 participants’ perception of brand responsibility is directly proportional to their purchase intention, meaning that the higher the purchase intention, the higher the proportion of participants who believe that the brand is not responsible. There is a clear polarization in attitudes towards participants who are willing to purchase all or most of the endorsed products. And for choosing affordable products, participants generally held a neutral attitude.

Figure 13: Participants with different levels of endorsed products purchase have different attitudes towards the brand after the scandal involving the brand endorsers in Group 1.

Figure 14: Participants with different levels of endorsed products purchase have different attitudes towards the brand after the scandal involving the brand endorsers in Group 2.

Figure 15: Whether participants with different levels of purchase for endorsed products are willing to purchase products from the brand after the scandal involving the brand's endorser in Group 1.

Figure 16: Whether participants with different levels of purchase for endorsed products are willing to purchase products from the brand after the scandal involving the brand's endorser in Group 2.

Based on the above data, H5 has been rejected. The number of types of celebrity endorsed products purchased by participants doesn’t affect their attitude towards the brand or whether they purchase products from that brand. And customers who purchase the most endorsed product categories will not be affected by the most celebrity scandals and brand terminations. The most affected group should be the participants who purchase affordable products.

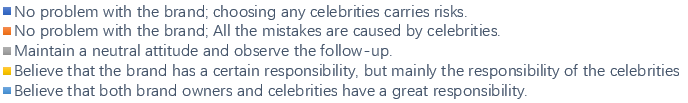

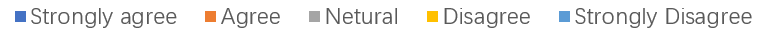

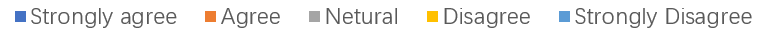

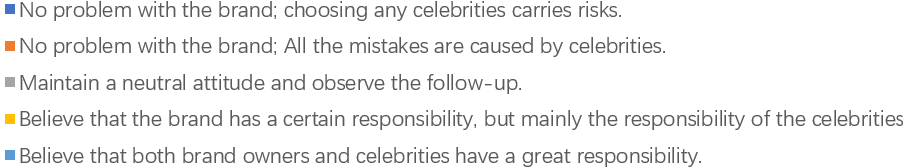

4.1.5. Celebrity Attention Level

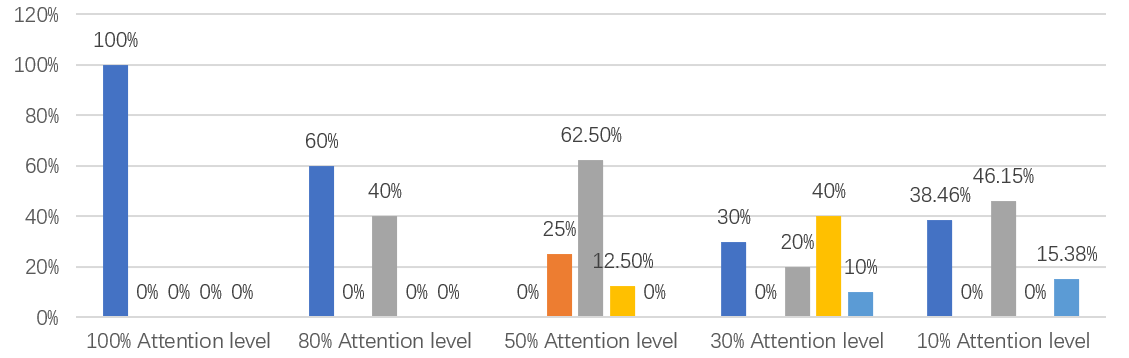

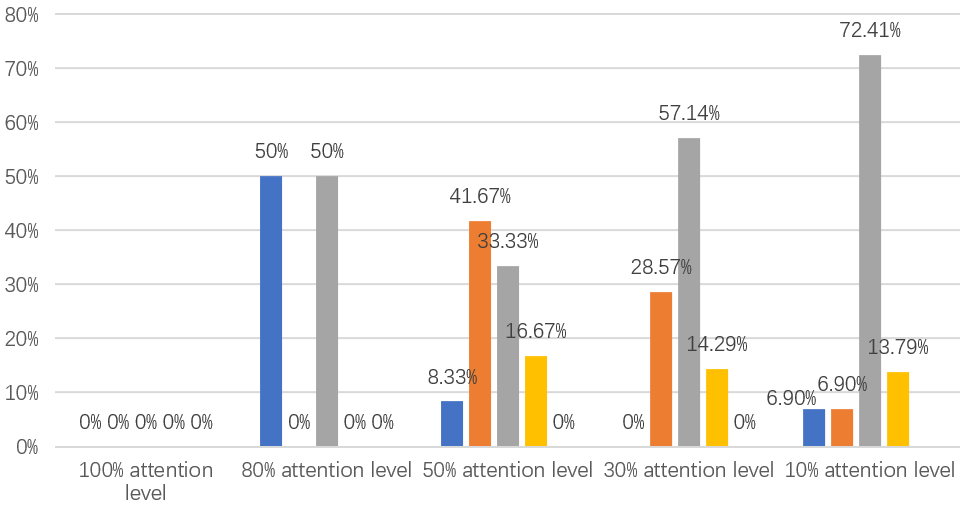

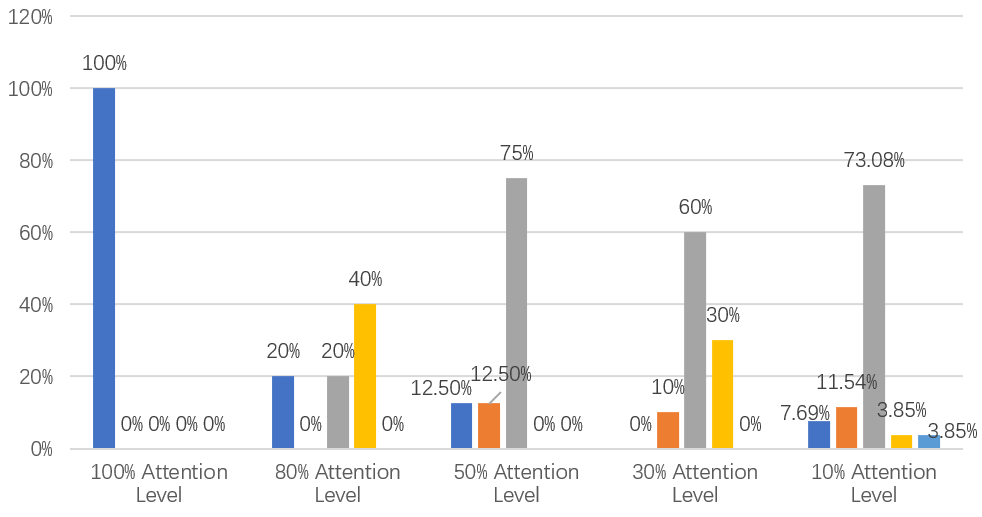

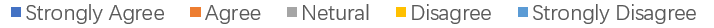

According to Figure 17 and Figure 18, in group 1, participants' attitudes on brand responsibility and purchase intention tend to be neutral as their attention to celebrities decreases. In the high attention group, participants had more extreme views and purchase intentions towards brand responsibility, while the low attention group showed more neutral attitudes. The willingness to purchase decreases with decreasing attention, while the neutral attitude increases with decreasing attention.

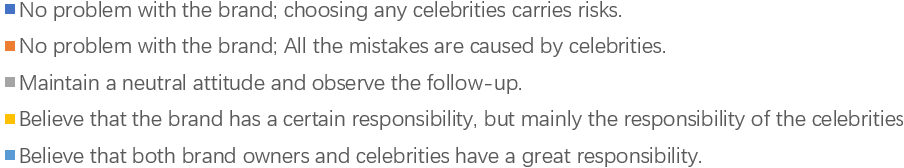

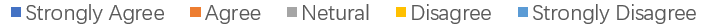

In group 2, according to Figure 19 and Figure 20, as the level of attention decreases, the participants' perception of brand responsibility shifts from a completely neutral attitude to a more neutral attitude and a belief that celebrity responsibility is greater. The purchase intention is higher in the high attention group, and as the attention decreases, the neutral attitude increases and the purchase intention decreases.

Figure 17: Participants with different levels of attention to celebrities' attitudes towards the brand after scandals involving brand endorsers in Group 1.

Figure 18: Participants with different levels of attention to celebrities' attitudes towards the brand after scandals involving brand endorsers in Group 2.

Figure 19: Whether participants with different levels of attention to celebrities are willing to purchase products from a brand after a scandal involving a brand endorser.

Figure 20: Whether participants with different levels of attention to celebrities are willing to purchase products from a brand after a scandal involving a brand endorser.

Based on the above data, H6 can only be partially accepted. The lower the level of attention paid to celebrities, the lower the support and purchase intention for the brand after knowing about celebrity scandals and brand termination of celebrity contracts. However, as attention decreases, attitudes towards the brand become more neutral. Similarly, in terms of purchasing intention, the lower the level of attention, the higher the proportion of subjects holding a neutral attitude.

4.2. Regression Model

According to Tables 1 and Table 2, the R-squared values of both models indicate a certain degree of variability in the models. The variability of group 1 is 33.2%, and the variability of group 2 is 37.16%. Because the adjusted squared values of both models are lower than the original R-squared value, both models contain some insignificant variables: age, gender, education, number of product categories purchased for endorsement, and attention to celebrities. The only statistically significant variable in both models is that after a celebrity scandal is exposed and terminated, customers' attitudes towards the brand have a significant positive impact on their purchase intention. The statistical p-value of F is less than 0.05 in both models. This indicates that even if some independent variables are not significant, the overall model is still effective in predicting purchase intention.

Table 1: Regression model of Group 1.

Coefficients | ||||

Estimate Std. | Std. Error | t value | Pr(>|t|) | |

(Intercept) | 0.276146 | 0.911851 | 0.303 | 0.763472 |

Gender | 0.033545 | 0.203837 | 0.165 | 0.870054 |

Age | 0.005088 | 0.131343 | 0.039 | 0.96928 |

Edu | 0.102931 | 0.189844 | 0.542 | 0.590488 |

Purchase | 0.190347 | 0.180666 | 1.054 | 0.297957 |

Attention | 0.126188 | 0.132796 | 0.95 | 0.347301 |

Attitude | 0.287023 | 0.079421 | 3.614 | 0.000785*** |

Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘ ’ 1 | ||||

Residual standard error: 0.6827 on 43 degrees of freedom | ||||

Multiple R-squared: 0.332, Adjusted R-squared: 0.2387 | ||||

F-statistic: 3.561 on 6 and 43 DF, p-value: 0.005954 | ||||

Table 2: Regression model of Group 2.

Coefficients: | ||||

Estimate Std. | Std. Error | t value | Pr(>|t|) | |

(Intercept) | 1.2081 | 0.86628 | 1.395 | 0.1703 |

Gender | 0.3495 | 0.22274 | 1.569 | 0.12395 |

Age | 0.13362 | 0.08503 | 1.571 | 0.1234 |

Edu | -0.08804 | 0.15063 | -0.585 | 0.56193 |

Purchase | -0.08825 | 0.14175 | -0.623 | 0.53684 |

Attention | 0.17544 | 0.12212 | 1.437 | 0.15808 |

Attitude | 0.29742 | 0.08225 | 3.616 | 0.00078 *** |

Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘’ 1 | ||||

Residual standard error: 0.7391 on 43 degrees of freedom | ||||

Multiple R-squared: 0.3716, Adjusted R-squared: 0.2839 | ||||

F-statistic: 4.238 on 6 and 43 DF, p-value: 0.001947 | ||||

5. Conclusion

Although most participants made rational choices when brands select unscrupulous endorsers, the minority may not support the brand. Based on the above phenomena, brands should pay attention to the following points: (1) Brands should carefully study the purchase power and budget of celebrities' fans. Even though some potential customers may be willing to purchase endorsed products, they will not pay for products because of limited budgets. The most quintessential examples are luxury and automobile. (2) Brands should pay attention to product itself. Not all customers will purchase endorsed products originally unused to get celebrity derivatives. (3) Brands should conduct risk assessments and carefully select endorsers. If brands choose a celebrity who has a large fan base and strong purchase power but has controversial reputation, sales and attention may increase significantly during the endorsement period. However, if such celebrities are involved in scandals, the negative impact is also significant. (4) Potential customers' attitudes towards brands after brand endorsers scandal have the greatest impact on customers further purchase intentions. Therefore, when the endorsers encounter problems, it is crucial for brands to respond and provide solutions to the problem.

According to the experiment, some limitations still occurred: (1) The overall number of participants in this experiment is relatively small and may not be universal. The experiment also lacks participants aged above 40 and participants with educational backgrounds lower than undergraduate. (2) Category restrictions. Only jewelry which not necessity was selected. We cannot guarantee that participants will have similar choices in other products. (3) Cultural influence. The participants in this experiment are all Chinese nationals. Due to cultural influence, if a celebrity in China encounters serious moral or legal issues, audience's evaluation of the celebrity will sharply decline. However, we are uncertain about participants attitudes from other cultural backgrounds towards similar events.

References

[1]. Zhibiao Wang. (2024) The celebrity effect of traffic "enclosure" and the digital survival of industrial culture, Shenzhen University Daily (Humanities and Social Sciences Edition).

[2]. Jinyi Yang, Hongxing Yang, Shishan, and Xiaoqiang Zhao. (2022) Marketing Strategy Analysis of Products Derived from Fan’s Economy—Take Yuying Wenchuang Company as an Example, 2022 3rd International Conference on Big Data Economy and Information Management.

[3]. Weimeng Yuan, Meimei Chen. (2024) Study on the Influence of E-commerce Anchor Characteristics on Users' Intention to Purchase Love and Present [J] E-Commerce Letters.

[4]. Norzalina Noor, Sukor Beram, Fanny Khoo Chee Yuet, et al. (2023) Bias, Halo Effect and Horn Effect: A Systematic Literature Review, International Journal of Academic Research in Business &Social Sciences, Vol 13, Issue 3, E-ISSN: 2222-6990.

[5]. Yang, W., Loang, O.K. (2024). Systematic Literature Review: Behavioural Biases as the Determinants of Herding. In: El Khoury, R. (eds) Technology-Driven Business Innovation. Studies in Systems, Decision and Control, vol 223. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-51997-0_7.

[6]. Ogochi Ajaegbu, Emmanuel Ikpegbu, Rebecca Olorunpomi. (2024) Social Media Framing of Domestic Violence Against Men in Nigeria: A Review of Literature, Covenant Journals Communication, Vol 11, No1.

Cite this article

Yang,J. (2024). The Impact Discussion of Celebrity Endorsements on Customer Choice from the Perspective of Behavioral Economics --- Taking Pandora's Sales on the Online Platform as an Example. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,128,140-152.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Financial Technology and Business Analysis

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Zhibiao Wang. (2024) The celebrity effect of traffic "enclosure" and the digital survival of industrial culture, Shenzhen University Daily (Humanities and Social Sciences Edition).

[2]. Jinyi Yang, Hongxing Yang, Shishan, and Xiaoqiang Zhao. (2022) Marketing Strategy Analysis of Products Derived from Fan’s Economy—Take Yuying Wenchuang Company as an Example, 2022 3rd International Conference on Big Data Economy and Information Management.

[3]. Weimeng Yuan, Meimei Chen. (2024) Study on the Influence of E-commerce Anchor Characteristics on Users' Intention to Purchase Love and Present [J] E-Commerce Letters.

[4]. Norzalina Noor, Sukor Beram, Fanny Khoo Chee Yuet, et al. (2023) Bias, Halo Effect and Horn Effect: A Systematic Literature Review, International Journal of Academic Research in Business &Social Sciences, Vol 13, Issue 3, E-ISSN: 2222-6990.

[5]. Yang, W., Loang, O.K. (2024). Systematic Literature Review: Behavioural Biases as the Determinants of Herding. In: El Khoury, R. (eds) Technology-Driven Business Innovation. Studies in Systems, Decision and Control, vol 223. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-51997-0_7.

[6]. Ogochi Ajaegbu, Emmanuel Ikpegbu, Rebecca Olorunpomi. (2024) Social Media Framing of Domestic Violence Against Men in Nigeria: A Review of Literature, Covenant Journals Communication, Vol 11, No1.