1.Introduction

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the United States has become the sole superpower with the end of the American-Soviet rivalry. However, with the establishment of the European Union, the rapid economic growth of developed countries such as Japan, and the rapid development of developing countries such as China, India, and Southeast Asia, the world has shown a trend of multipolarity. Although the GDP growth rate of developed countries has slowed down in recent years, they are still in a dominant position in global trade. Through innovative R&D and after-sales services, developed countries have gained a large amount of added value, while developing countries are mostly engaged in trade in primary products or intermediate processing trade and can only gain a relatively small amount of added value. It is worth exploring the reasons for the constraints on developing countries' innovative capacity and micro-market dynamism. The second part of the paper compares the impact of adopting extractive and inclusive economic systems on economic growth in different countries. The third part analyzes the reasons for the differences in the economic trends of countries with different economic systems by analyzing GDP trends and the share of private sector output in GDP for the USSR, the United States, and Russia. This paper provides implications for transforming economic systems to stimulate micro-market dynamics in developing countries.

2.Literature Review

2.1.Extractive Economic Systems

The distinction between extractive and inclusive economies draws on Acemoglu's approach. A quintessential illustration of an extractive economic system is the former Soviet Union. Following the Patriotic War and World War II, it operated under a planned economy, which streamlined the shift to a wartime economy and enabled a swift socio-economic recovery in the post-war era. However, the stagnation in total factor productivity growth rates and the deceleration of output in the USSR post-1970 can be attributed to the state's stringent control over resource allocation, price inflexibility, and a pervasive lack of transparency within the economic framework. [1, 2]. To maintain nuclear parity with the United States, the Soviet Union emphasized the allocation of its premium resources toward the defense sector. It even retained surplus capacity within the metallurgical industry, civilian machinery manufacturing, and the energy domain, among others, to guarantee that these resources could be redirected to military production as required. This led to much idle capacity and reduced productivity [3]. After the arms race with the United States in the 1980s and the impact of the oil crisis, Gorbachev tried to reform the Soviet Union's market economy, but not only did he fail to liberalize price controls, but he also transformed the planned economy into a rent-seeking machine [4, 5]. After the failure of internal reforms, the USSR was unable to seek financial and policy support from international organizations as it failed to become a member of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank [4]. Eventually, the Soviet Union was headed for disintegration.

After the dramatic changes in Eastern Europe, socialist countries such as Poland, Germany, and Hungary carried out reforms, shifted their political systems to capitalism, and carried out drastic reforms of their economic systems. Russia, the main successor to the Soviet Union, also began to adopt “shock therapy” during the Yeltsin regime. The economic reforms implemented were intended to abolish price controls and promote market-oriented changes. Nevertheless, the Yeltsin administration overlooked the critical issue of insufficient institutional frameworks necessary for the transition from a planned economy to a market-based system [5]. On the one hand, price deregulation contributed to the rapid rise in the prices of essential commodities, which depleted the savings of the Russian people [5]. On the other hand, Russia's industrial structure was still dominated by state-owned enterprises and monopolies, which made its privatization reforms superficial. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) had to go through complex regulatory agencies before they could start operating, which severely inhibited market activity and innovation [5]. Meanwhile, after the IMF helped Russia to open its capital markets prematurely for reforms, and after suffering from the impact of international lobbying, the default of the Russian government's debt in 1998 led to a sharp fall in the ruble. This led directly to the failure of Russia's “shock therapy”. Not only did the socialist countries fail in reforming their economic systems, however, countries such as South Africa and Burma, which were influenced by the democratic ideas of the United States after the Second World War, also set up highly centralized military governments after seizing power from the colonizers through the means of armed wars. Centralized rule inevitably gave rise to an economic system with strict control over resources, which in turn inhibited market dynamics and fostered corruption [6, 7].

2.2.Inclusive economic Systems

Before the Civil War, plantations in the southern United States, utilizing their resource endowments and a minimum level of consumption catering only to blacks, grew their economies at a higher rate than those in the north. The extreme oppression of blacks in the South severely curtailed the incentives for the black community to be prosperous and productive, and in the two decades following the end of the Civil War, the rest of the U.S. economy grew at a rapid pace, while the South's economic development lagged [8]. The emancipation of blacks was made possible by the protections of the U.S. Constitution for human rights and private property rights, and the U.S. was thus able to free up a large portion of its labor force to engage in industrial production activities. During the shift from an agrarian economy to an industrial one, the alternating governance model of the Democratic and Republican parties prompted the government to prioritize the welfare of the populace when implementing economic policies, rather than enacting measures that could harm the public for the benefit of those in power or their influential backers[9]. Even in the transition to a post-industrial economy (knowledge-based economy), the U.S. political system has continued to make timely adjustments to facilitate the development of urban agglomerations [10]. In addition to safeguarding the political framework and upholding the rule of law, a robust central bank, specifically the U.S. Federal Reserve System, plays a crucial role in ensuring the nation's swift economic expansion. During the global financial crisis of 2007-2009 and the ensuing European sovereign debt crisis, the zero lower bound on interest rates rendered conventional monetary policy ineffective. In response, the Federal Reserve implemented a substantial infusion of liquidity to catalyze the recovery of the U.S. economy through the mechanism of "quantitative easing." [11].

The inclusive economic systems of Europe and the United States, while contributing to their own economic growth, also deeply influenced the establishment of institutions in their colonies. Singapore, a former colony, introduced the British judicial system and the Dutch business philosophy when it became an independent country from Malaysia in 1965. These advanced systems have contributed to Singapore's rapid economic growth and its rise to the ranks of developed countries. Unlike Western countries such as the United States and Europe, Singapore has established a system of elitist politics and elected public officials [12]. Based on meritocracy, the integrity of the Singaporean government is ensured through comprehensive and effective anti-failure measures and high salaries [12]. This system guarantees the linkage of the people, chambers of commerce, and trade unions with the government as well as the creation of a favorable business environment in Singapore to attract large amounts of foreign investment [13]. Although Japan was not colonized, it was taken over by the United States after its defeat in World War II. This led to a gradual change from a military government system to a capitalist system. Despite maintaining the emperor as a symbolic figure, post-war Japan implemented a system of checks and balances to uphold judicial independence, mirroring the frameworks of British and American governance. Additionally, through its industrialization efforts, Japan accelerated its alignment with global narratives and embraced deregulation. [14].

3.Methodology

3.1.Data

To visualize the impact of extractive and inclusive economic regimes on a country's economic trends, this paper selects nominal GDP data from the CEIC database for the Soviet Union and the United States for 1970-1990. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the former Union Republics transformed their economic systems in search of economic growth. The trends in GDP for Belarus (BLR), Kazakhstan (KAZ), Ukraine (UKR), and Uzbekistan (UZB) are representative of the changes that occurred in these countries as they transformed their economic systems after leaving the Soviet Union. The choice of the four countries mentioned above does not mean that the other member countries are not important, but their GDP is lower than the four countries mentioned above and the trends are almost similar. Finally, the GDP share of Russian SMEs is from Rosstat and the GDP share of U.S. private sector output was collected from CEIC in 2019.

3.2.Results

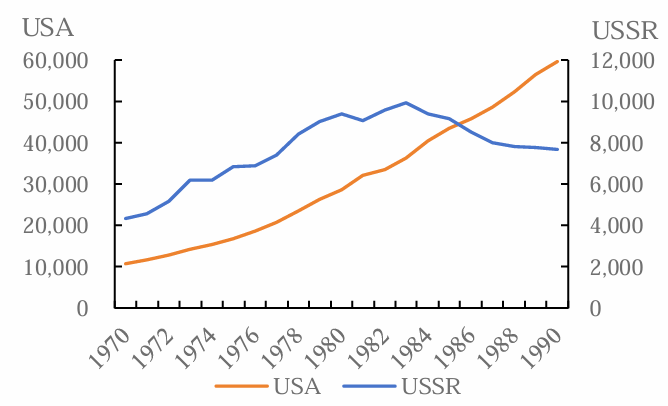

Figure 1 shows that not only did the U.S. GDP continue to grow at a high rate during the Second Cold War, but the output was much higher than that of the Soviet Union (U.S. GDP averaged about $3,085.7 billion in 1970-1980, compared with $767.4 billion for the Soviet Union). Although Figure 1 shows a downward trend in the Soviet economy beginning in 1983, the roots of the downturn were laid much earlier. First, a highly centralized planned economy was adopted under Stalin to rapidly revive the economy. The Soviet regime implemented a policy of compulsory nationalization, seizing control of banks, major industrial firms, small enterprises, and private retail operations, while enforcing stringent price regulations and monopolizing foreign trade. As social stability was established, the inherent drawbacks of a centrally planned economy became increasingly evident. Government oversight dictated production levels, resulting in the market's diminished influence on pricing mechanisms, which in turn created disincentives for businesses to manufacture goods and significantly hampered advancements in Total factor productivity. Secondly, the Prague Spring movement interrupted the reforms of the ‘new economic system’ under Brezhnev. Subsequently, Brezhnev reinstated the system of life tenure in leadership positions, leading to a massive loss of senior government officials. This resulted in the next two leaders taking office at a senior age for very short terms, preventing fundamental changes in the economy. In addition, nepotism began to prevail within the Communist Party, and the government's criteria for selecting cadres shifted to personal loyalty to Brezhnev. This highly centralized economic system led to serious rent-seeking problems, as the ‘power roster’ of Soviet cadres at all levels of the Communist Party was deeply tied to the power to allocate resources. Although the USSR became a superpower on par with the United States during the Brezhnev era, this status was achieved by devoting large amounts of resources to heavy and military industries, which severely constrained development in the field of technology. As the world transitioned into the era of large-scale integrated circuit computing, the USSR fell behind in the technological race against the United States. Even today, neither the USSR nor its subsequent entities have managed to develop products that rivaled the innovations of IBM or Apple during that period.

Figure 1: Trend of GDP

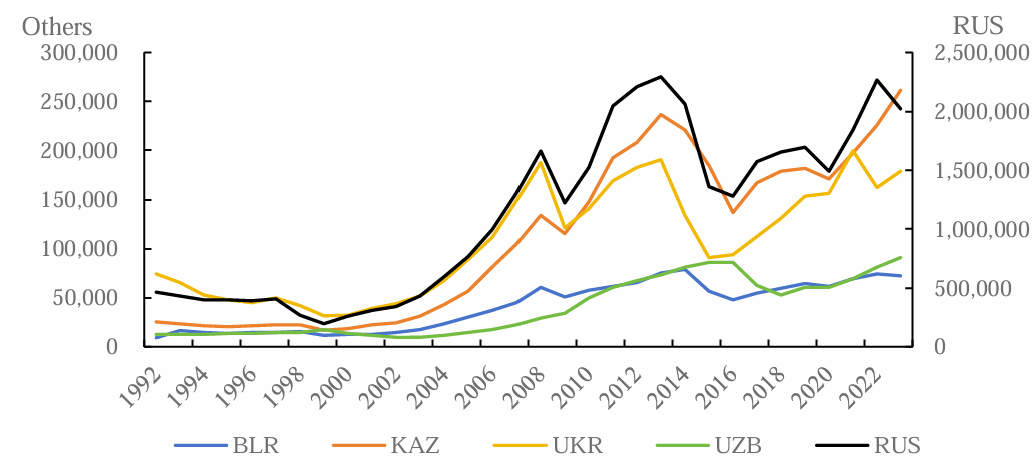

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1992, Russia and 14 other member countries started to try “shock therapy” to stimulate their economies. As can be seen in Figure 2, the GDP trends for Russia (RUS), Belarus (BLR), Kazakhstan (KAZ), Ukraine (UKR), and Uzbekistan (UZB) for the period 1993-2023 show a generally upward trend, but with large fluctuations. The rapid decline in Russia's GDP in the period 1992-2000 can be considered as the pain period of “shock therapy”, but with the collapse of the ruble, the “shock therapy” was declared a failure. The failure of that reform was attributed, on the one hand, to the fact that the International Monetary Fund, in its policy guidance to Russia, ignored the fact that the country was in a state of anarchy and that the new institutions had not yet been fully established [5]. In the absence of a robust central banking authority during that period, Russia uncritically adhered to the International Monetary Fund's directives and hastily liberalized its capital markets. Rather than drawing in sustainable long-term investments, the fragile financial landscape became a magnet for opportunistic lobbyists, culminating in defaults on sovereign debt and the subsequent devaluation of the ruble.

Figure 2: Trend of GDP

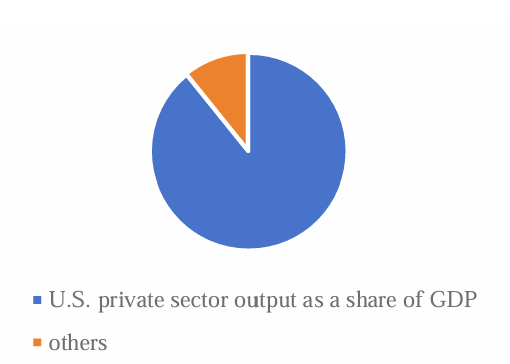

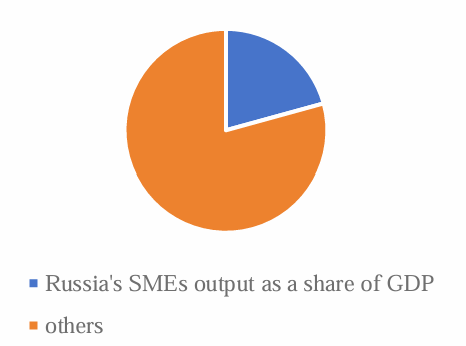

On the other hand, it can be attributed to the fact that the Russian government still has considerable control over resources. Although private property rights are protected to some extent, the economy is still dominated by the state economy. The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), through its transformation into the United Russia Party (URP), continues to hold directorships and other leadership positions in state-owned enterprises. This has allowed the party-constituted elite to continue to have power over the distribution of resources, and thus the problem of rent-seeking is unlikely to cease to exist. Small and medium-sized enterprises in Russia may resort to corrupt practices to secure the necessary permissions amidst a complex approval process. As can be seen from the comparison of Figures 3 and 4, the share of Russian SMEs in total output is only about 20 percent, while private sector output in the United States is as high as 89 percent of GDP. The protection of private property rights and the market economy system in the United States have fully stimulated the participants' productivity and creativity, which is one of the reasons for the economic growth of newspapers in the United States.

Figure 3: U.S. private sector output as a share of GDP in 2019

Figure 4: Russia share of GDP in 2019

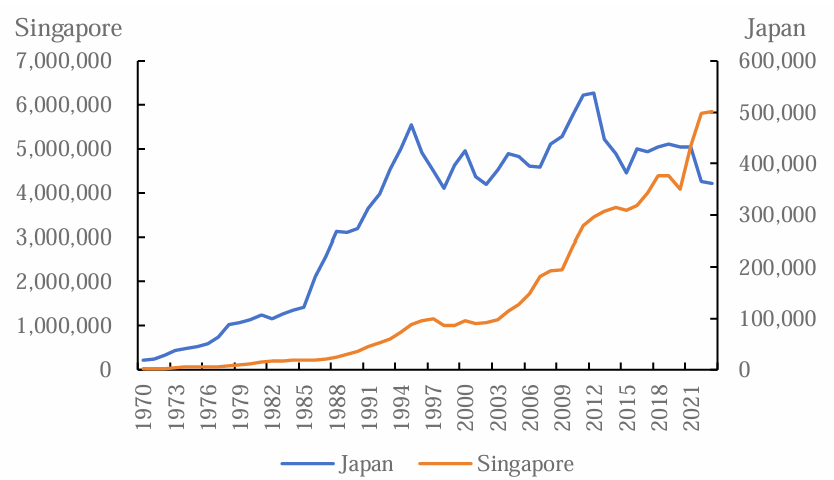

This paper does not suggest that a large proportion of state-owned enterprises in society necessarily inhibit economic development. Figure 5 shows that Singapore's economy has been experiencing high growth since 1970, thanks to the Singaporean government's leadership through state-owned enterprises to drive other enterprises to participate in international trade. However, Singapore's SOEs are slightly different from Russia's and even many developing ones. As a colony, Singapore was exposed to the Anglo-American political system at an earlier stage, so after its independence, it introduced the Anglo-American rule of law system to ensure the inviolability of private property rights. Unlike Russia, where the president appoints local officials, Singapore employs elite politics in the selection of government officials.12 Integrity within the government is ensured through legal constraints and high salaries. At the same time, the possibility of centralized politics is fundamentally eliminated through the mobilization of trade union assemblies and grassroots organizations rather than the government-imposed allocation of resources to lead development policies.

Although not a colony, Japan's takeover by the United States after its defeat in World War II allowed it to overhaul its political system. Figure 5 also shows that the Japanese economy maintained a high growth rate until the 1990s. Although it seems to have fallen into an economic downturn after the 1990s, its average annual GDP from 1990-2023 still managed to reach about $4.7 trillion. This is partly attributed to Japan's separation of powers between the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary, modeled on the United States, which provided institutional support for the opening of the Japanese market. On the other hand, Japan seized the opportunity of the development of large-scale integrated circuit computers led by the United States, led by the Ministry of International Trade and Industry, in conjunction with Hitachi, Mitsubishi, Fujitsu, Toshiba, Japan Electric five companies to attack semiconductor technology. In the heyday of Japan's economic growth (1986), Japan's semiconductor products 45% of the world, while the United States accounted for only 37%

Figure 5: Trend of GDP

4.Conclusion

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union was able to gain parity with the United States by devoting most of its resources to heavy industry and the military industry through a highly centralized planned economy. However, this form of so-called collective ownership resulted in unclear property rights and a lack of protection of private property rights, which severely inhibited the motivation and creativity of workers. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Russian government, as the successor to the Soviet Union, did not fundamentally reform the political system. The former communists continued to control the distribution of resources under a different name, which in turn led to the unresolved problem of rent-seeking. In contrast, although Japan and Singapore are also government-led in their participation in global trade, the major operations, research, and development are still done by private enterprises, which is in line with the basic conditions of such small-sized countries that need to integrate national resources. The autonomy of such private enterprises was due to the legal protection of private property rights and the establishment of a relatively fair environment in Japan and Singapore. This paper analyses the inhibitory effect of the centralized economic system on economic growth only from the perspectives of private property rights and resource control, but it does not analyse in depth the main causes of the centralized economic system. Therefore, the creation of a fair and secure environment should also be considered by the Governments of developing countries undergoing market economy reforms. Governments should not only improve policies for the protection of private property rights and intellectual property rights but also ensure social equity to reduce the exploitation of workers by the privileged class and monopolistic enterprises.

References

[1]. Ickes, B. W. (2018). Output fall—Transformational recession. In The new Palgrave dictionary of economics, edited by Macmillan Publishers Ltd, (pp. 9928–9939). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

[2]. Voskoboynikov, I. B. (2021). Accounting for growth in the USSR and Russia, 1950–2012. Journal of Economic Surveys, 35(3), 870-894.

[3]. Cooper, J. (2013). The Russian economy twenty years after the end of the socialist economic system. Journal of Eurasian Studies, 4(1), 55-64.

[4]. Åslund, A. (2011). The demise of the Soviet economic system. International Politics, 48(4), 545-561.

[5]. Desai, P. (2005). Russian retrospectives on reforms from Yeltsin to Putin. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(1), 87-106.

[6]. Lodge, T. (1998). Political Corruption in South Africa. African Affairs, 97(387), 157-187.

[7]. Jones, L. (2014). The political economy of Myanmar’s transition. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 44(1), 144-170.

[8]. Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2013). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. Crown Currency.

[9]. Blinder, A. S., & Watson, M. W. (2016). Presidents and the US economy: An econometric exploration. American Economic Review, 106(4), 1015-1045.

[10]. Hacker, J. S., Hertel-Fernandez, A., Pierson, P., & Thelen, K. (2022). The American political economy: markets, power, and the meta politics of US economic governance. Annual Review of Political Science, 25(1), 197-217.

[11]. Bernanke, B. S. (2020). The new tools of monetary policy. American Economic Review, 110(4), 943-983.

[12]. Bellows, T. J. (2009). Meritocracy and the Singapore political system. Asian Journal of Political Science, 17(1), 24-44.

[13]. Chong, A. (2007). Singapore's political economy, 1997–2007: Strategizing economic assurance for globalization. Asian Survey, 47(6), 952-976.

[14]. Chen, L. (2008). Institutional inertia, adjustment, and change: Japan as a case of a coordinated market economy. Review of International Political Economy, 15(3), 460-479.

Cite this article

Dong,R.;Dong,Y. (2025). Analyzing the Causes of the Slowdown in Economic Growth--From the Perspective of the Economic System. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,162,132-139.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Business and Policy Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Ickes, B. W. (2018). Output fall—Transformational recession. In The new Palgrave dictionary of economics, edited by Macmillan Publishers Ltd, (pp. 9928–9939). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

[2]. Voskoboynikov, I. B. (2021). Accounting for growth in the USSR and Russia, 1950–2012. Journal of Economic Surveys, 35(3), 870-894.

[3]. Cooper, J. (2013). The Russian economy twenty years after the end of the socialist economic system. Journal of Eurasian Studies, 4(1), 55-64.

[4]. Åslund, A. (2011). The demise of the Soviet economic system. International Politics, 48(4), 545-561.

[5]. Desai, P. (2005). Russian retrospectives on reforms from Yeltsin to Putin. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(1), 87-106.

[6]. Lodge, T. (1998). Political Corruption in South Africa. African Affairs, 97(387), 157-187.

[7]. Jones, L. (2014). The political economy of Myanmar’s transition. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 44(1), 144-170.

[8]. Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2013). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. Crown Currency.

[9]. Blinder, A. S., & Watson, M. W. (2016). Presidents and the US economy: An econometric exploration. American Economic Review, 106(4), 1015-1045.

[10]. Hacker, J. S., Hertel-Fernandez, A., Pierson, P., & Thelen, K. (2022). The American political economy: markets, power, and the meta politics of US economic governance. Annual Review of Political Science, 25(1), 197-217.

[11]. Bernanke, B. S. (2020). The new tools of monetary policy. American Economic Review, 110(4), 943-983.

[12]. Bellows, T. J. (2009). Meritocracy and the Singapore political system. Asian Journal of Political Science, 17(1), 24-44.

[13]. Chong, A. (2007). Singapore's political economy, 1997–2007: Strategizing economic assurance for globalization. Asian Survey, 47(6), 952-976.

[14]. Chen, L. (2008). Institutional inertia, adjustment, and change: Japan as a case of a coordinated market economy. Review of International Political Economy, 15(3), 460-479.