1 Introduction

1.1 Research Background

As social media and the internet evolve, more and more individuals are expected to buy and sell things online. In light of the advent of COVID-19, a greater number of individuals are inclined to purchase cheaper items [1]. The decision to purchase and sell through online C2C marketplaces is especially popular among foreign students, who often arrive from other countries and are unfamiliar with local brands. Furthermore, due to the reduced cost of second-hand items, students are inclined to choose them. It is usual for transactions to occur via official C2C platforms (such as eBay or Taobao) or non-sanctioned channels (e.g., WeChat). In this method, the price of the used product is difficult to define and would essentially vary amongst individuals, as the market price has no bearing on it. The price issue is the key point of contention between sellers and buyers in the market. When purchasing used goods, purchasers are inclined to choose moderate or high quality. Considering that people don't like to lose things and that the item has already been used, one would expect a lower price [2].

On the other hand, this may vary when vendors establish prices. Unquestionably, the price should be less than that of comparable new items or daily necessities. Nonetheless, owners are likely to place a far greater value on the goods than buyers, as relationships between owners and things are likely to be formed through usage [3]. Thus, increasing the product's worth for the owner. Based on what was said before about product valuation, this study tends to focus on the C2C market and product valuation.

C2C is a market for transactions between owners and purchasers [4]. Usually, a third-party platform is used to do business on the market, since the loyalty and happiness of the platform's current customers are likely to attract new customers and get their attention [5]. By allowing a third party to communicate product information, the product may be sold. Some merchants might use C2C channels, while others might decide to only sell through social media like WeChat. For instance, starting a group chat with hundreds of individuals and providing product information enables the product to receive exposure. During a transaction, it's common for buyers to think that a product's price is too high, especially if it's used. However, sellers don't agree with this. In the C2C market, the issue of how buyers and sellers may value a product differently is gaining importance.

The C2C market for commodities is a crucial market segment since it is where consumers are most likely to participate. This market may contain leisure items, garden supplies, personal care items, etc. In other words, the items on this market are likely to be utilized in people's daily lives. A growing number of people have joined the market, according to the findings of a study. Individuals are more inclined to sell used items. 72% of eBay sellers in the United States tend to sell pre-owned things during COVID. In addition, family and personal care products are often the most popular C2C online purchases, followed by leisure and sports items [1]. Moreover, this market is characterized by extreme valuation disparities between customers and proprietors. For instance, researchers observed that 41.3% of eBay users had a tendency to underestimate the price of a product [6]. The findings indicate that a substantial portion of the population is likely to be involved in the commodities market, highlighting the need to explore this field.

Current research on C2C tends to concentrate on numerous elements, including the definition of the C2C market, the online market for commodities, market regulations, and market-influencing variables. In the beginning, researchers often compared C2C and B2C marketplaces and discussed the impact of social media on the market [7]. On the basis of this, several researchers investigated the market performance of platforms that offer goods and everyday necessities [8]. In addition, scholars have examined the regulations and laws governing online C2C transactions, including payment systems, feedback systems, and authorization [9]. On the basis of this information, academics have also explored which laws govern C2C market transactions [10]. Lastly, contemporary research seeks to investigate many systems and characteristics that may impact online transactions in the market, such as cheating on online auctions, reputation information, and various strategies for dealing with these variables [11]. In general, research focuses on the online transaction procedure and the market factors that may have a crucial impact.

1.2 Research Gap

However, there are a few areas that the present study has neglected to investigate. First, there is a lack of research on online transactions that do not follow the official system, such as buying behavior through social media when selling a second-hand product (e.g., posting product information on media and seeking buyers) when the transaction is not going through systems like eBay or Taobao. Even though it may be difficult to monitor, it is becoming increasingly common for students to acquire and sell used goods. Consequently, it is crucial to include this market sector in the C2C industry. In addition, there is a dearth of research on the business-to-consumer sector for everyday essentials. This is significant because, in addition to the market for antiquities and works of art, the second-hand market in which individuals are most likely to participate consists of everyday essentials. A market with such significance and population should thus be investigated. Last but not least, research on the pricing of items for the C2C market is lacking. In the C2C market, setting prices for used goods has been a key difficulty. This issue is crucial since pricing in C2C is unlikely to reflect market prices because the product's worth is heavily impacted by the fact that it has been previously utilized. In addition, because the goods have been previously used, purchasers and owners may have vastly different opinions on their value. Due to the significance of the issue in this sector, it is necessary to collect data.

Consequently, based on the aforementioned constraint, this study will concentrate on both the C2C market for commodities and how owners and purchasers value the commodity differently in the C2C market. This is particularly true for online C2C transactions that do not go through official C2C platforms. The endowment effect refers to how different owners and buyers value a commodity; it means that those who own the product may value it more than those who do not [12]. With this in mind, the objective of this study was to determine the extent to which the endowment effect influences pricing in the online C2C commodity market for Chinese international students, as well as the extent to which this applies to C2C transactions that do not go through official C2C platforms. This study will focus on how to apply the endowment effect to the market and look at how the effect works in its new setting.

1.3 Structure of This Paper

In order to investigate this question, this research will experiment with how owners and buyers would value a product when selling or buying. Two conditions would be created: seller and buyer conditions, and participants would be asked to attend both. In this case, the valuation of a product would be represented by prices. Higher prices given to the product would indicate a higher valuation, and vice versa. At last, participants would be asked to choose which factor they think is the most important when buying or selling. Overall, this study would provide a discussion on the extent to which the endowment effect has influenced pricing in the C2C market.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Definition & Development

The endowment effect refers to the idea that people who own an item tend to value it higher than people who do not own the product [12]. This is also referred to as the WTP-WTA gap. In other words, the difference between the buyer’s maximum of willing to pay and the seller’s minimum of willing to accept. The endowment provides insights regarding preferences and how people value things. This is essential in economics, Psychology, Marketing etc.

The development of the endowment effect began with the idea that people are unlikely to fully empathise with others and appreciate individual differences between perspectives [13]. This includes buyers and sellers, creating an egocentric empathy gap between individuals. Based on this effect, research proposed the endowment effect. The endowment effect was initially argued as primarily due to loss aversion. Researchers found that people view the negative aspects of giving up a particular item as greater than the positive aspects of acquiring it [14]. Therefore, people tend to propose a higher price when selling the item because they are more concentrated on the “giving up” behaviour. Nevertheless, later research argued that other factors could also play an essential role in eliciting the endowment effect. For example, some argued from the evolutionary approach by suggesting that the endowment effect occurred due to the aim of surviving and offering greater growth for offspring [15]. In other words, a greater resource valuation increases the likelihood that individuals and offspring may survive. Other researchers have also argued that from a cultural perspective, a link between cultural dimensions (individualistic and collectivistic) and the endowment effect could be created. For example, researchers suggested that greater independence (individualistic culture) is associated with a more significant endowment effect [16]. Nowadays, with the development of research in this area, although loss aversion is likely the leading paradigm for the endowment effect, the effect has been recognised as due to various reasons rather than loss aversion only.

The endowment effect can be tested in two ways, the exchange paradigm and the valuation paradigm. The exchange paradigm refers to observing whether the participants would be more reluctant to change than expected. If so, then the endowment effect could be predicted [12]. The valuation paradigm refers to investigating the extent that buyer’s maximum price that they are willing to pay (WTP) is lower than the minimum price that seller willing to accept (WTA) [12]. The difference is referred to as the WTP-WTA gap. As the gap increase, an increased endowment effect could be predicted.

2.2 Important Results

There are three main arguments that current research suggests. First, due to ownership, the endowment effect is evident in buying and selling behaviour. Secondly, egocentricity is essential in making ownership leads to the valuation difference between buyers and sellers. At last, the application of endowment effect into the C2C market.

Firstly, some researchers emphasized the importance of ownership in eliciting the effect. Morewedge and Giblin experimented with the effect and found that when buyers are also the product owners, they tend to predict a price as high as sellers predicted who own the product [12]. Therefore, this demonstrated that when people own the item, the valuation tends to be the same. This indicates the importance of owning an item when valuing an item. By replicating prior research on the endowment effect, researchers argued that ownership is essential due to the emotional connections that may be built between self and the object – emotional attachment [17]. Researchers argued that consumers might experience a strong emotional bond with a product, especially when positive emotions have occurred when using the product [3].

Furthermore, an emotional connection can be built before individual use the item [18]. In this way, the owners may value a product higher due to the emotional connections built when using it in the past. The higher valuation increases the price owners may set for the product, thus leading to price estimation differences between buyers and sellers.

Based on research about the importance of ownership, researchers argued that the human nature of egocentricity plays an essential in making ownership leads to the valuation difference between buyers and sellers. For example, Boven and colleagues found that asking participants to either sell or buy a mug makes the seller's lowest acceptance price three times higher than the buyer's maximum willingness to pay [13]. In this case, it demonstrates the seller's tendency to overestimate what buyers are willing to pay, while buyers underestimate the seller's boundary of willingness to sell. Researchers argued that this is because people tend to overestimate the similarity between self and others, meaning that, by being egocentric - assuming the need or want of self and others are the same, participants are disabled to fully understand others' perspectives, leading to the phenomenon of overestimation or underestimating other's valuation. Based on this, later research emphasized the point of egocentricity by suggesting that although buyers have offered higher prices with one commodity through interacting with sellers, nevertheless, they are unable to do so for another commodity [19]. This demonstrates that participants cannot fully understand others' perspectives and ultimately alter their prices. Because of the inability to empathize with others, the difference is that sellers own the product. At the same time, buyers and buyers cannot fully appreciate the difference, thus leading to a valuation difference between buyers and sellers.

Based on the importance of ownership on the endowment effect, it seems that the effect may also exist in the market. By collecting data in the C2C market, where owners and buyers are involved, researchers observed a significant valuation difference between owners and buyers. For example, on eBay, the data revealed customers' apparent preference for low prices. For example, it was found that 41.3% of the customers on eBay tend to underbid the product price during an auction [6]. This revealed the phenomenon that customers tend to predict a lower price of a product than the sellers, while the fact that nearly 50% of the participants have underbid the price indicated the price estimation differences between buyers and sellers. Moreover, platforms with a large proportion of overpriced products are likely to be severely complained about by customers. For example, a ticket reseller called Viagogo received many complaints due to its misleading and unfair conduct [20]. On the other hand, researchers found that it is common for sellers to tend to price a product higher [21]. Therefore, this emphasized that owners tend to do a higher product valuation, while buyers may result in a lower valuation in comparison, thus leading to a large price estimation difference between buyers and sellers.

On the other hand, some other researchers have argued that the significant difference in price that buyers and sellers estimated is because of other confounding variables, such as feasibility and desirability focus, rather than the endowment effect – the influence of ownership. For example, research suggested that individual owners may overprice an item because of the underestimation of the importance of the feasibility aspect of the item [22]. This is because when individuals are selling an item, they are no longer using the product. Thus, they tend to concentrate on the desirability of the product. For example, when selling a concert ticket, the seller tends to focus on the reputation of the performers rather than whether it is easy to park a car near the concert. On the other hand, the buyers should consider those perspectives, which may lower the ticket's value. Thus, it creates a price prediction difference rather than due to loss aversion.

2.3 Summary

Overall, it has been stated that there is a price estimate disparity between suppliers and purchasers. Some early studies indicated that it is related to ownership, while other research described how the egocentric character of humans causes ownership to trigger the endowment effect. Price estimate disparities were also seen in the C2C sector, with buyers preferring lower prices and sellers having a tendency to set high prices. Nonetheless, others have claimed that this phenomenon is not attributable to the endowment effect but rather to other confounding variables.

In accordance with the preceding research, this study seeks to determine to what degree the endowment effect affects prices in the online C2C commodities market for overseas Chinese students. This purpose has dual significance. Initially, it offers the opportunity to apply the endowment effect to the market, mostly to demonstrate how it functions in markets where transactions are not conducted via formal C2C platforms. This deepens C2C market research and provides insight into how consumers' and sellers' attitudes may differ from the conventional market, which is vital for consumer psychology.

This experiment tests the hypothesis that participants will prefer a greater price when they are sellers rather than when they are buyers, based on the available research findings. In addition, ownership is primarily responsible for this distinction. In this instance, the endowment effect would be quantified as ownership since, according to previous research, ownership is a substantial component contributing to the difference in valuation between purchasers and sellers. The assessment of pricing would also be used to determine the value of a particular commodity. A higher price means that the product is worth more, while a lower price means that the product is worth less.

3 Methodology

3.1 Research Design

To test the objective, two circumstances will be established: customers (who do not own the goods) and sellers (who do own the product) in the C2C market. As a vendor or buyer, both parties would be asked how they estimate the price of a specific good. The difference in the prices projected by the two groups would serve as a measure of the valuation difference—an indication of the endowment effect. Participants will be prompted to complete the seller's condition first and then the buyer's condition three days later in a repeated-measures design. Individual differences are avoided by employing a repeated-measures strategy. Moreover, it enables the researcher to determine the amount to which the price may be affected purely by ownership—thus the endowment effect.

3.2 Data Collection

Questionnaire Design. Questionnaires are used to test the endowment effect in this study. Asking participants to select a price range they are willing to choose reveals their product valuation. In addition, it allows the researcher to observe the pattern of pricing clearer by creating distribution graphs.

30 Chinese international students, 19 females and 11 males aged between 19 and 22 (M=20.17, SD=1.26), were recruited through self-selected sampling. Chinese international students who have been engaged in the C2C market by selling through WeChat group chats were recruited because international students are people who are most likely to be engaged in the C2C market (especially when moving into a new place), where the transactions were going through unofficial C2C platforms such as WeChat, which makes them more likely to represent the population engaged in this market.

Participants were asked to do a questionnaire in seller condition at first. The questionnaire asks participants to estimate the price of a given object when selling them as a second-hand product through WeChat group chats. Three objects with different original prices (150, 60, 40) were provided to ensure the answer applied to different prices. At last, participants were asked how they determine the price of a second-hand product when they are buying or selling based on their prior experiences in the C2C market.

Participants answered the questions by selecting different options, where the prices were categorised in different ranges (e.g., 130-149; 110-129). This is to avoid inaccuracy. Selecting a number on a scale decreases participants' perception of different numbers. However, categorising the numbers into ranges allows participants to see in detail which numbers are higher or lower. Thus, assisting them in making a more credible choice.

Procedure. First of all, participants will be informed that this study aims to test either buyer's or seller's preference of prices for a product in the C2C market. Deception has been used to prevent participants from changing their decision based on the known effect. Participants will be instructed to participate in the seller condition first. Participants were asked to choose their preferred price when selling a second-hand pot, cup, and book in the seller's condition. The original price of those products was given to avoid that different estimations have occurred due to different original prices participants have assumed. Three products with different prices were given to enhance the credibility of the answer. Participants were reminded that those products had been once used by themselves for one year. Reasons for choosing the particular choice were asked after each question. Participants will be asked to participate in the seller condition three days after completing the seller condition. For the buyer condition, participants were asked to choose their preferred price when buying a second-hand pot, cup, and books. Information given to the sellers was also provided for participants. In addition, both conditions reminded participants that they are selling the item through WeChat groups they have joined rather than through C2C platforms such as Taobao or eBay. At the end of the questionnaire, a debrief would be given, introducing the endowment effect and the true aim of the study. In addition to the questionnaire, a question that aims to examine participants' attention was designed to ensure that they are paying attention to the questionnaire by asking participants to select a particular choice.

The right to withdraw has been mentioned throughout the study, where they can withdraw at any time during the study and the right to withdraw the data after participating. Participants were also reminded about their anonymity – numbers will represent them in the data rather than names. In addition, the data used in this study will be destroyed once it has been analysed.

Ways to Identify Unreliable Answers. There are two methods for identifying dubious study results. Initially, a question to determine if respondents had read the questions carefully was inserted between the questions: "If you are selling a second-hand cup that you have used for a year and that originally cost 80 RMB, how much would you wish to receive? Please choose "70" In order to pass, participants must read the questions to the finish. This ensures that each participant has attentively read the questions. Additionally, the amount of time spent answering the questions would be evaluated. As all questions are multiple-or single-choice, only responses submitted within 3 minutes were evaluated. This is meant to stop people from going to websites like Taobao to find out what the average price of the item in question is on the C2C market.

3.3 Data Collection

The data would be analysed by performing distribution graphs. Therefore, this allows the pricing pattern to be visualised by researchers, thus providing a more explicit analysis. In addition, a t-test would be used to see whether there is a statistically significant difference between the two conditions. This helps to quantify the difference between sellers’ and buyers’ pricing. Finally, the mean would be used instead of ranges when analysing the data.

4 Results

4.1 Price Preferences

The data will be shown in terms of distribution graphs. Through distribution plots, it allows a comparison between the conditions. More importantly, it allows the pattern to be observed. In addition, a t-test would be performed to see if the price preference between the two conditions has reached a statistical difference. This would be based on the p-value. The result is recognised as insignificant if the p-value is larger than 0.05. On the other hand, it is recognised as statistically significant. The t-test would be performed based on the hypothesis that the seller condition prefers higher prices compared to the buyer condition.

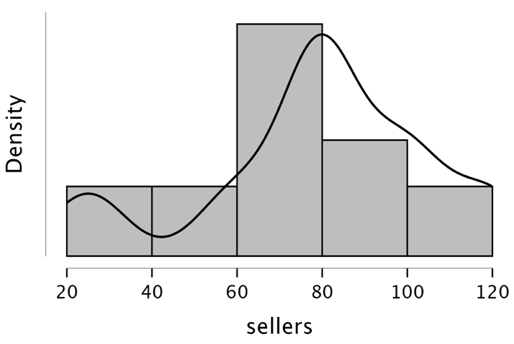

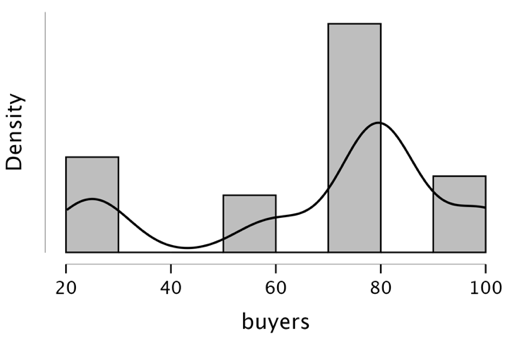

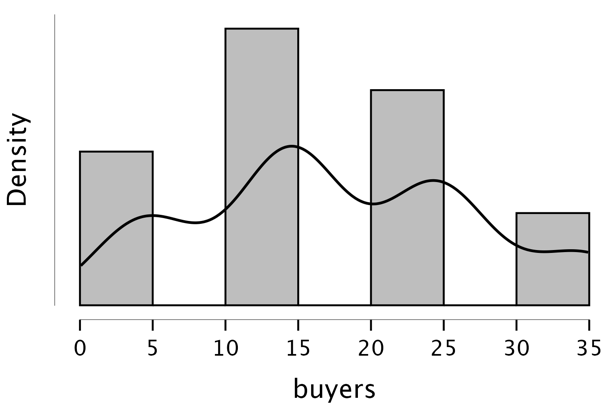

There tends to be a significant difference in price preference between the seller condition (M=79.354, SD=27.115) and the buyer condition (M=68.979, SD=25.533, t (23) = 4.182, p<.001) (Table 1, Figure 1 & 2).

In the case of a second-hand pot, where the original price is 150RMB, participants tend to prefer higher prices when selling the product (M=79.354, SD=27.115). Regarding Figure 1, the data pattern of the seller condition tends to be negatively skewed, meaning that participants tend to choose higher prices. Participants in the seller condition tend to choose a price ranging from 70 to 89 RMB at most (41.67%), while none of the participants have chosen to sell the product at the original price or a bit lower (130-149 RMB). In addition, a few participants chose a value smaller than 50 (8.33%), and several chose a value between 110 to 129 RMB (8.33%). Overall, this demonstrates a pattern of choosing higher prices. In addition, a leptokurtic pattern of the data indicated that participants’ data are concentrated and distributed around the mean.

On the other hand, when participants participated in the buyer condition, the line tended to follow a platykurtic pattern, meaning that the data points were widely distributed around the mean. Although the price range between 70 and 89 RMB is still the price that has been most frequently chosen (50%), more participants tend to select a price lower than 50 RMB, which is the lowest price range (20.83%). Furthermore, no participants selected the range from 110 to 129 RMB, whereas some participants selected this range before in the seller condition (8.33%). Few participants selected the range from 90 to 109 RMB (16.67%), where it was the second most popular range when they were in the seller condition (25%). Overall, although both conditions tend to select the range that is nearly half of the original price at most, the buyer condition tends to perform a tendency to select lower prices. The difference has reached a statistical difference (Table 2).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of second-hand pot

sellers | buyers | |||

Valid | 24 | 24 | ||

Missing | 0 | 0 | ||

Mean | 79.354 | 68.979 | ||

Std. Deviation | 27.115 | 25.533 | ||

Skewness | -0.643 | -0.855 | ||

Std. Error of Skewness | 0.472 | 0.472 | ||

Minimum | 25.000 | 25.000 | ||

Maximum | 119.500 | 99.500 | ||

Distribution Plots

Fig 1. Distribution plot for sellers (second-hand pot)

Fig 2. Distribution plot for buyers (second-hand pot)

Table 2. Paired-sample t-test for second-hand pot, comparison made between sellers & buyers

Measure 1 | Measure 2 | t | df | p | Cohen's d | ||||||||

sellers | - | buyers | 4.182 | 23 | < .001 | 0.854 | |||||||

Note. For all tests, the alternative hypothesis specifies that sellers is greater than buyers. | |||||||||||||

Note. Student's t-test. | |||||||||||||

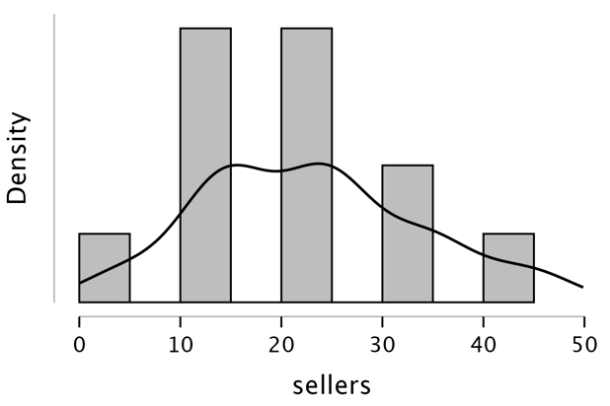

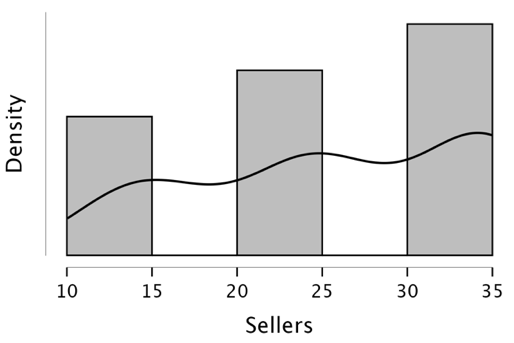

There is no significant difference in price preferences between the seller condition (M=22.833, SD=10.901) and the buyer condition (M=17.833, SD=9.631, t(23) = 1.313, p=.101).

According to Figure 3, in the case of selling second-hand cups with an original price of 60 RMB, the distribution line tends to demonstrate a positively skewed pattern, which demonstrates a tendency to predict lower prices. In the seller condition, most participants choose a value ranging between 20 to 29 (33.3%) and 10-19 (33.3%). While no participants decided to sell the item at the original price, some chose to sell it slightly lower than the original price – between 40 to 49 (8.33%). Several participants also chose to sell it for the lowest price – 1 to 9 RMB (8.33%). Table 3. Descriptive statistics for second-hand cup

sellers | buyers | ||||

Valid | 24 | 24 | |||

Missing | 0 | 0 | |||

Mean | 22.833 | 17.833 | |||

Std. Deviation | 10.901 | 9.631 | |||

Skewness | 0.358 | 0.201 | |||

Std. Error of Skewness | 0.472 | 0.472 | |||

Minimum | 4.500 | 4.500 | |||

Maximum | 44.500 | 34.500 | |||

On the other hand, according to Figure 4, the preferred price tends to form a positive skew. Similar to the seller condition, most participants tend to choose a value ranging between 20 to 29 (29.17%) and 10-19 (37.5%). Nevertheless, more participants preferred buying second-hand cups with the lowest price – 1 to 9 RMB (20.83%) compared with the seller's condition (8.33%). However, the difference did not form a statistical significance. Overall, although the buyer condition for second-hand cups tends to prefer lower prices than sellers, the difference did not form a statistical significance.

Fig 3. Distribution plot for sellers (second-hand cup)

Fig 4. Distribution plot for buyers (second-hand cup)

Table 4. Paired-sample t-test for second-hand cup, comparison made between sellers & buyers | |||||||||||||

Measure 1 | Measure 2 | t | df | p | Cohen's d | ||||||||

sellers | - | buyers | 1.313 | 23 | 0.101 | 0.268 | |||||||

Note. For all tests, the alternative hypothesis specifies that sellers is greater than buyers. | |||||||||||||

Note. Student's t-test. | |||||||||||||

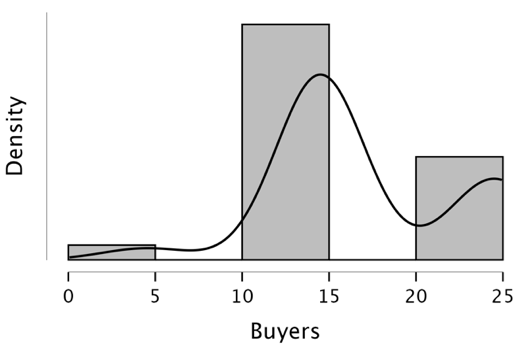

There is a statistically significant difference in price preferences between the seller condition (M=26.167, SD=8.165) and the buyer condition (M=17.000, SD=5.361, t (23) = 7.695, p<.001) (Table 5).

According to Figure 5, the distribution line forms a positively skewed pattern, meaning higher prices tend to be preferred when selling second-hand books. Most participants tend to sell the book at nearly the original price – 30 to 39 RMB (41.67%), or the slightly lower price – 20 to 29 RMB (33.33%) and no participants wish to sell it at the lowest price. Overall, this demonstrates a tendency to sell at high prices for books.

On the other hand, when participants changed to the buyer condition, they tended to prefer a significantly lower price of second-hand books. Unlike what participants have performed in the seller condition, a positive skewness tends to be demonstrated by the distribution line in Figure 6, indicating the preference for low prices. No participants preferred a price nearly the original price, which was the most popular choice when they were sellers. A large proportion of buyers prefer lower prices, such as more than 50% below the original price (70.83%). Overall, in the case of selling second-hand books, sellers tend to prefer a significantly higher price than buyers, where the difference has reached statistical significance.

Table 5. Descriptive statistics for second-hand book | |||||

Sellers | Buyers | ||||

Valid | 24 | 24 | |||

Missing | 0 | 0 | |||

Mean | 26.167 | 17.000 | |||

Std. Deviation | 8.165 | 5.316 | |||

Skewness | -0.329 | 0.237 | |||

Std. Error of Skewness | 0.472 | 0.472 | |||

Minimum | 14.500 | 4.500 | |||

Maximum | 34.500 | 24.500 | |||

Fig 5. Distribution plot for sellers (second-hand book)

Fig 6. Distribution plot for buyers (second-hand book)

Table 6. Paired-sample t-test for second-hand book, comparison made between sellers & buyers | |||||||||||

Measure 1 | Measure 2 | t | df | p | |||||||

Sellers | - | Buyers | 7.695 | 23 | < .001 | ||||||

Note. For all tests, the alternative hypothesis specifies that Sellers is greater than Buyers. | |||||||||||

4.2 Reasons

As the researcher has also asked participants to identify why they chose the particular price range, the reasons have been organized as bar graphs.

According to Figure 7, every participant (except those who chose to skip the question) has chosen the importance of functions when considering how much it could be sold. This means whether the product could still function well after it has been used for one year. In addition, 12 participants also chose the importance of the year that the product has been used. Some also state aesthetics – whether the object still looks nice, and the possibility of the product could be sold as important factors when setting the price. Nevertheless, no participants chose the option of losing ownership, and emotional connection with the object may influence their price setting.

Fig 7. Reasons of choosing the price when selling

According to 20 participants who answered this question, all participants agreed that whether the product could still function well plays an essential role when evaluating whether the price is suitable from the buyers’ perspective (Figure 8). Most participants have also agreed that years have been used and the market price of the second-hand product matters – that is, the price of the second-hand product commonly sold on the C2C market. Some also mentioned that they were looking for the lowest price when buying, which they think is more important than other factors.

Fig 8. Reasons of choosing the price when buying

5 Discussion

Overall, the results mostly confirm the hypothesis, indicating that participants prefer greater pricing when selling as opposed to purchasing. According to the data, seller conditions tend to induce a stronger price preference than buyers and have attained statistical significance. Nevertheless, although the majority of the data supports the trend, a few did not detect a statistically significant correlation (second-hand cups).

Overall, the result implies that sellers place a higher value on a product than do purchasers. When participants place a high value on a product or deem it indispensable, they tend to establish a higher price. As with the majority of goods examined by the research, sellers who possess the product often place a greater value on it than purchasers who do not. For instance, when participants were asked to behave as if they were owners while selling used books, they tended to opt to sell the product at a price close to its original cost. However, when they are purchasers, they often select a price that is barely one-third of the initial cost. When participants were invited to sell or purchase used pots and cups, similar instances happened. The majority of sellers select prices greater than half, whereas the majority of buyers select the lowest price or a price lower than half. As pricing can be seen as an indication of value, this study shows that there is a value gap between sellers and buyers in the online C2C market for commodities when buying and selling are not done through formal C2C platforms.

Prior research on the phenomenon suggests that sellers may desire greater prices when selling than buyers, which is contradictory to the current conclusion. This is because sellers place a larger value on a product than customers [13]. The inclination to charge high prices might be viewed as elevating a product's value. This creates a disparity in valuation between buyers and sellers. The outcome may be explained by the preceding explanations that the difference is due to the item's ownership status and that valuing it higher or lower results in a price difference. Moreover, the absence of empathy between individuals may exacerbate the disparity.

Nonetheless, this study concerns the extent to which the variation in valuation was attributable to the endowment effect. According to a previous study, it appears that the endowment effect is mostly driven by the difference between owning and not owning the goods—purchasers and owners evaluate things differently due to ownership. Purchasers, on the other hand, do not, and they are unable to fully comprehend the perspective of the other [13]. However, when participants were asked to evaluate the elements that may impact their pricing based on their past experiences in the C2C market, neither the importance of ownership nor the emotional connection to the product were selected. This calls into question how much the endowment effect contributed to the discrepancy. Regarding the outcome, merchants appear to place a high value on the function and the time it has used. Some vendors would additionally examine the likelihood of the product's commercial success. This indicates that pricing may be affected by market rivalry or product type. For instance, a pot may be simpler to sell than a computer monitor. Therefore, further reductions may be required for the screen. This means that sellers in the C2C market who don't use C2C online platforms rely mostly on product knowledge and competition instead of being affected by ownership or the emotional relationships they form.

From the standpoint of the purchaser, the functions and the number of years it has been employed are equally crucial. On the other hand, a number of purchasers have stated that they place a premium on the product's price and desire to get it at the lowest possible cost. This resulted in some participants selecting the lowest cost available for all goods. In addition, while purchasing second-hand things, purchasers place a high emphasis on market pricing; some claim that they would also visit C2C online marketplaces such as Taobao or eBay to determine the product's average selling price. This demonstrates that buyers and sellers have distinct viewpoints and are influenced by various things. Consequently, it is questionable whether the difference in value between buyers and sellers was caused by ownership.

There are factors other than the endowment effect that contribute to the occurrence of a value gap between owners and purchasers. For example, various complicated variables may have a significant impact on purchasing and selling. For instance, researchers discovered that vendors prefer to focus more on the product's attractiveness, but purchasers tend to focus more on the product's practicability [22]. This means that sellers may establish pricing based on the product's aesthetic qualities or its brand, which are the aspects that contribute to the product's desirability. On the other hand, customers are more inclined to concentrate on how to utilize the goods and any potential obstacles they may encounter. This is not related to ownership; this results in a difference in value.

This study has also shed light on how varying product kinds in the C2C commodity market may result in disparate values. In response to a question asking participants to identify the aspect that has impacted their pricing preferences, a number of individuals likened the commodities market for books to that of other items. For instance, while acting as sellers, they believe that books are less likely to be damaged or lose value over time than other objects, such as pots. As a result, they prefer to provide a higher price, one that is close to the book's original cost but not for other titles. This consequently informs future researchers that, while researching prices in a certain industry, various goods within the market may provide different results.

Overall, this research is consistent with the previous result that sellers and owners had different valuations. Nonetheless, it should be questioned if the difference was primarily attributable to the endowment effect. Due to the fact that this study focuses exclusively on the commodities market and the buying and selling behaviour that occurs outside of formal online C2C platforms, it provides insight into the possibility that the pricing mentality may vary depending on the market type. When selling commodities such as pots, for instance, sellers may place a larger value on the possibility of selling out than on other aspects. However, when selling long-used decorations, they may be impacted by ownership and emotional ties. Buyers may also experience a similar phenomenon. Using a C2C platform may potentially affect the product's value. By selling or purchasing a product via online C2C platforms, product information may be shown more effectively, thus impacting the product's value. So, it makes sense that people will value and be affected by different things in different types of markets.

Based on the findings discussed above offers several suggestions for the future online C2C market. First, the price estimation differences between the sellers and buyers demonstrate that sellers and buyers hold different perspectives, leading to valuation differences. The difficulty of understanding others' perspectives and empathising with them is becoming increasingly important, especially when people are losing something (e.g., money or the product you once owned). One solution to the problem is to build a "bridge" that allows both sides to understand the other. For example, to ask buyers to add a pie chart of how the price was formed, such as 50% was due to the manufacturing and production price, 20% was due to after-sale service and so on. This process of creating the chart allows the buyers to view why the price was charged, making them more willing to pay the price. More importantly, it allows the sellers to evaluate whether the price is reasonable, which could avoid overpricing to some extent.

From the buyer's perspective, buyers need to provide suggestions for the product (e.g., through questionnaires). In this way, it allows the sellers to view whether the price is suitable and, if not, why customers thought it was overpriced. Therefore, creating a bridge that allows the buyers and sellers to switch information enables both perspectives to empathise with each other, which may decrease the price differences. Thus, decreasing the unwillingness to lose either product or money may increase sales and customer satisfaction.

6 Conclusions

In the online C2C market of commodities, the problem of sellers and buyers valuing a product differently appears frequently. Recent research has argued that this is because of ownership, and because people cannot fully appreciate and empathise with others, a gap between buyers and sellers has been formed. By investigating whether the gap also appears in the C2C market of commodities, where buying and selling behaviours are going through WeChat group chats, it has been found that the valuation difference exists in the market to a large extent. Nevertheless, it is questionable whether the valuation difference is solely due to the influence of ownership. Participants seem to highly value other factors, such as the year used, function, and market price. This finding also provides an insight that it might be because buyers and sellers value and are influenced by different factors in different types of markets.

The findings of this paper could be implicated in how the C2C online platform could work in order to improve buyer's and seller's satisfaction. For example, making sellers know what others want could make their way of selling more desired by the buyers. In addition, from the educational perspective of marketing or consumer psychology, this research reminds people that different C2C markets, especially those involved platforms such as WeChat group chats, could involve a different mindset when valuing a product. Therefore, people should be reminded that different C2C markets make a difference.

There are some strengths and limitations in this study. This includes discussions on participants, experiment design and findings interpretation.

First, the use of international students who have once engaged in the C2C market by either buying or selling products through WeChat group chats allows the research finding to represent the seller's and buyer's performance in the real market. In addition, it allows the study to investigate a particular branch of the market – where buying and selling behaviours are not going through official C2C platforms. Finally, it provides an insight that different mindsets could be involved when engaging in a different market.

In addition, the repeated measure design used by this study has eliminated individual differences, meaning that making the same group of participants do both conditions ensures that the finding has not been influenced by the fact that people are different. For example, suppose an independent sample design was used. In that case, one participant could choose to sell the product at the original price may also mean that the participant is likely to buy the product at the original price, but not directly suggesting that the product has been valued high or overpriced. Observing different performances in the two perspectives by the same participant has emphasised the different perspectives of sellers and buyers.

Nevertheless, it is essential to consider that the repeated measure design was used; it is still possible that participants remembered their answers three days before. Therefore, they will likely choose the same answer again to maintain the same as before. This may alter the result of this study – participants are choosing the price because it has been previously chosen but not because they would sell/buy the product at this price. Therefore, it is possible that the credibility of the finding to be questioned.

Additional to the limitation of this study, it is vital to evaluate the credibility of the results. For example, ownership may be essential, but participants did not realise it. Although no participant stated that ownership is an essential factor when pricing, it is important to note that participants did not answer that does not necessarily indicate there was no influence from the factor, but rather, participants have not recognized it.

Lastly, the number of participants may restrict the research's applicability. In other words, the sample size of 24 is insufficient to reflect the entire international student population. Consequently, it is feasible that the findings might change if the study was repeated with a different sample of individuals.

On the basis of the aforementioned constraints, this study advises that future research duplicate the study with a bigger sample size to increase the credibility of the findings. Furthermore, to target various C2C market types This research demonstrates that buyers' and sellers' mentalities and preferences may have varied in various markets, such as online and face-to-face C2C marketplaces or markets for commodities, technology, furniture, etc. Therefore, researchers must conduct further studies on various C2C markets. In addition, this study recommends more investigation into the causes of the endowment effect. This study questions whether the variation in value between buyers and sellers is exclusively attributable to ownership. The conversation should continue with subsequent studies.

References

[1]. Goddevrind, V., Schumacher, T., Seetharaman, R., & Spillecke, D. C2C e-commerce: Could a new business model sell more old goods? | McKinsey. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/technology-media-and-telecommunications/our-insights/c2c-ecommerce-could-a-new-business-model-sell-more-old-goods (2021).

[2]. Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Experiments in Environmental Economics, 1, 143–172. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185 (2018).

[3]. Mugge, R., Schoormans, J. P. L., & Schifferstein, H. N. J. PRODUCT ATTACHMENT: DESIGN STRATEGIES TO STIMULATE THE EMOTIONAL BONDING TO PRODUCTS. Product Experience, 425–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-008045089-6.50020-4 (2008).

[4]. Leonard Lori. Attitude influencers in C2C e-commerce: Buying and selling. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279712105_Attitude_influencers_in_C2C_e-commerce_Buying_and_selling (2012).

[5]. Ke Er, W. A Study on Relationship Between Customer Relationship Management (CRM) and Customer Satisfaction on Taobao Website in Johor Bahru. Journal of Arts & Social Sciences, 3, 1. (2020).

[6]. Garratt, R. J., Walker, M., & Wooders, J. Behavior in second-price auctions by highly experienced eBay buyers and sellers. Experimental Economics, 15(1), 44–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-011-9287-3 (2012).

[7]. AlSheikh, S. S., Shaalan, K., & Meziane, F. Consumers’Trust and Popularity of Negative Posts in Social Media: A Case Study on the integration between B2C and C2C Business Models. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=8256364 (2017).

[8]. Li, D., Li, J., & Lin, Z. Online consumer-to-consumer market in China-A comparative study of Taobao and eBay. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2007.02.010 (2007).

[9]. Li, Q., & Liu, Z. Research on Chinese C2C E-Business Institution Trust Mechanism: case study on Taobao and Ebay(cn). https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=4340712 (2007).

[10]. Yue, X., & Xie, J. Research on the consumer behavior in C2C market. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=6010852 (2011).

[11]. Yamamoto, H., Ishida, K., & Ohta, T. Modeling Reputation Management System on Online C2C Market. Computational & Mathematical Organization Theory, 10, 165–178. (2004).

[12]. Morewedge, C. K., & Giblin, C. E. Explanations of the endowment effect: An integrative review. In Trends in Cognitive Sciences (Vol. 19, Issue 6, pp. 339–348). Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2015.04.004 (2015).

[13]. Boven, V., Dunning, D., & Loewenstein, G. Egocentric Empathy Gaps Between Owners and Buyers: Misperceptions of the Endowment Effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(1), 66–76. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3S14.79.1.66 (2000).

[14]. Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. H. Anomalies: The Endowment Effect, Loss Aversion, and Status Quo Bias. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1257/JEP.5.1.193 (1991).

[15]. Huck, S., Kirchsteiger, G., & Oechssler, J. Learning to Like What You Have – Explaining the Endowment Effect. The Economic Journal, 115(505), 689–702. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1468-0297.2005.01015.X (2005).

[16]. Maddux, W. W., Yang, H., Falk, C., Adam, H., Adair, W., Endo, Y., Carmon, Z., & Heine, S. J. For whom is parting with possessions more painful? cultural differences in the endowment effect. Psychological Science, 21(12), 1910–1917. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610388818 (2010).

[17]. Shu, S. B., & Peck, J. Psychological ownership and affective reaction: Emotional attachment process variables and the endowment effect. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 21(4), 439–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCPS.2011.01.002 (2011).

[18]. Nägele, N., von Walter, B., Scharfenberger, P., Wentzel, D., & Scharfenberger philippscharfenberger, P. “‘Touching’” services: tangible objects create an emotional connection to services even before their first use. Business Research, 13, 741–766. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40685-020-00114-0 (2020).

[19]. van Boven, L., Loewenstein, G., & Dunning, D. Mispredicting the endowment effect:: Underestimation of owners’ selling prices by buyer’s agents. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 51(3), 351–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-2681(02)00150-6 (2003).

[20]. Harris, C. Commerce Commission gets its day in court with ticket reseller Viagogo | Stuff.co.nz. https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/money/110351189/commerce-commission-gets-its-day-in-court-with-ticket-reseller-viagogo (2019).

[21]. Dirusso, D. J., Mudambi, S. M., & Schuff, D. Pricing strategy & practice Determinants of prices in an online marketplace. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610421111157946 (2011).

[22]. Irmak, C., Wakslak, C. J., & Trope, Y. Selling the forest, buying the trees: The effect of construal level on seller-buyer price discrepancy. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(2), 284–297. https://doi.org/10.1086/670020 (2013).

Cite this article

Sun,J. (2023). The Influence of Endowment Effect on The Online C2C Commodity Market for Chinese International Students. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,13,59-75.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Business and Policy Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Goddevrind, V., Schumacher, T., Seetharaman, R., & Spillecke, D. C2C e-commerce: Could a new business model sell more old goods? | McKinsey. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/technology-media-and-telecommunications/our-insights/c2c-ecommerce-could-a-new-business-model-sell-more-old-goods (2021).

[2]. Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Experiments in Environmental Economics, 1, 143–172. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185 (2018).

[3]. Mugge, R., Schoormans, J. P. L., & Schifferstein, H. N. J. PRODUCT ATTACHMENT: DESIGN STRATEGIES TO STIMULATE THE EMOTIONAL BONDING TO PRODUCTS. Product Experience, 425–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-008045089-6.50020-4 (2008).

[4]. Leonard Lori. Attitude influencers in C2C e-commerce: Buying and selling. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279712105_Attitude_influencers_in_C2C_e-commerce_Buying_and_selling (2012).

[5]. Ke Er, W. A Study on Relationship Between Customer Relationship Management (CRM) and Customer Satisfaction on Taobao Website in Johor Bahru. Journal of Arts & Social Sciences, 3, 1. (2020).

[6]. Garratt, R. J., Walker, M., & Wooders, J. Behavior in second-price auctions by highly experienced eBay buyers and sellers. Experimental Economics, 15(1), 44–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-011-9287-3 (2012).

[7]. AlSheikh, S. S., Shaalan, K., & Meziane, F. Consumers’Trust and Popularity of Negative Posts in Social Media: A Case Study on the integration between B2C and C2C Business Models. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=8256364 (2017).

[8]. Li, D., Li, J., & Lin, Z. Online consumer-to-consumer market in China-A comparative study of Taobao and eBay. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2007.02.010 (2007).

[9]. Li, Q., & Liu, Z. Research on Chinese C2C E-Business Institution Trust Mechanism: case study on Taobao and Ebay(cn). https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=4340712 (2007).

[10]. Yue, X., & Xie, J. Research on the consumer behavior in C2C market. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=6010852 (2011).

[11]. Yamamoto, H., Ishida, K., & Ohta, T. Modeling Reputation Management System on Online C2C Market. Computational & Mathematical Organization Theory, 10, 165–178. (2004).

[12]. Morewedge, C. K., & Giblin, C. E. Explanations of the endowment effect: An integrative review. In Trends in Cognitive Sciences (Vol. 19, Issue 6, pp. 339–348). Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2015.04.004 (2015).

[13]. Boven, V., Dunning, D., & Loewenstein, G. Egocentric Empathy Gaps Between Owners and Buyers: Misperceptions of the Endowment Effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(1), 66–76. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3S14.79.1.66 (2000).

[14]. Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. H. Anomalies: The Endowment Effect, Loss Aversion, and Status Quo Bias. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1257/JEP.5.1.193 (1991).

[15]. Huck, S., Kirchsteiger, G., & Oechssler, J. Learning to Like What You Have – Explaining the Endowment Effect. The Economic Journal, 115(505), 689–702. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1468-0297.2005.01015.X (2005).

[16]. Maddux, W. W., Yang, H., Falk, C., Adam, H., Adair, W., Endo, Y., Carmon, Z., & Heine, S. J. For whom is parting with possessions more painful? cultural differences in the endowment effect. Psychological Science, 21(12), 1910–1917. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610388818 (2010).

[17]. Shu, S. B., & Peck, J. Psychological ownership and affective reaction: Emotional attachment process variables and the endowment effect. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 21(4), 439–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCPS.2011.01.002 (2011).

[18]. Nägele, N., von Walter, B., Scharfenberger, P., Wentzel, D., & Scharfenberger philippscharfenberger, P. “‘Touching’” services: tangible objects create an emotional connection to services even before their first use. Business Research, 13, 741–766. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40685-020-00114-0 (2020).

[19]. van Boven, L., Loewenstein, G., & Dunning, D. Mispredicting the endowment effect:: Underestimation of owners’ selling prices by buyer’s agents. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 51(3), 351–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-2681(02)00150-6 (2003).

[20]. Harris, C. Commerce Commission gets its day in court with ticket reseller Viagogo | Stuff.co.nz. https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/money/110351189/commerce-commission-gets-its-day-in-court-with-ticket-reseller-viagogo (2019).

[21]. Dirusso, D. J., Mudambi, S. M., & Schuff, D. Pricing strategy & practice Determinants of prices in an online marketplace. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610421111157946 (2011).

[22]. Irmak, C., Wakslak, C. J., & Trope, Y. Selling the forest, buying the trees: The effect of construal level on seller-buyer price discrepancy. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(2), 284–297. https://doi.org/10.1086/670020 (2013).