1. Introduction

Business organizations operate in dynamic environments susceptible to external shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Anderson et al. suggest that under the conditions created by the pandemic, businesses came under “...unrelenting disruption, rapidly evolving customer expectations and an unprecedented pace of change” [1]. The rapidly evolving customer expectations can be attributed to changing consumer behaviors that included a drastic shift to dependence on digital solutions as witnessed in the cloud-computing space [1, 2]. Businesses can adapt to uncertain environments by using strategies like business model innovation (BMI). The concept of business model innovation comprises making changes to a business model through extension, adaptation, or innovation using new or existing capabilities [3]. It has been linked to organizational dynamics such as agility—defined as a business’s capacity to respond to environmental disruptions without compromising core competencies [4], and has been shown to have positive effects on organizational performance in volatile industries [3]. Consequently, it served as the theoretical foundation of the present paper. The present paper sought to examine the impact the pandemic had on businesses using Disney as a vignette. To do so, it sought to answer the following research questions:

RQ1: What were the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the tourism and entertainment sectors?

RQ2: How has the pandemic impacted Disney’s operations?

The paper adopts a case-study approach primarily using secondary information about Disney and its operations. Its focus on an old multinational entity that exudes qualities of a startup in specific sectors, such as the video-on-demand segment, makes it significant to the broader field of business research. Startups are more nimble than incumbents as it concerns innovation [5], yet Disney exhibits the agility associated with young companies due to its ability to align its products with emerging market needs. Thus, analyzing the effect the pandemic had on the company will serve as an example of how large companies can navigate uncertain environments created by external shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Introduction to Walt Disney Company and COVID-19

2.1. The Walt Disney Company

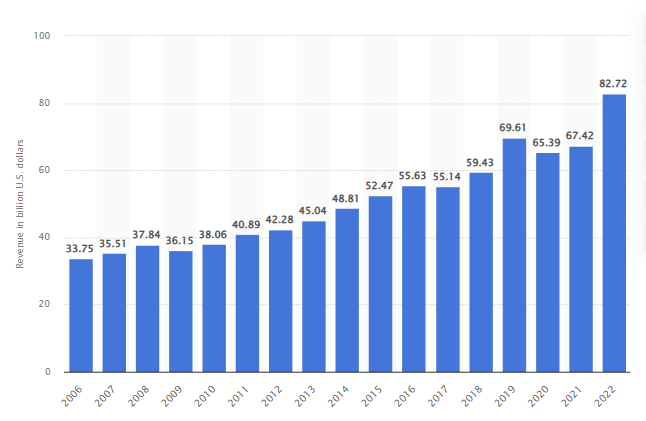

The Walt Disney Company was established as an animation studio by Walter (Walt) Disney in 1923, originally called the Disney Brothers Company due to the co-founding role played by his brother, Roy Disney [6]. According to Voigt et al., Disney began as a cartoon studio, directed by Walt’s ambitions to conquer California’s emerging film industry in the early 1920s [6]. Walt aimed to create cartoons that had clear story lines that appealed to family audiences, especially considering Hollywood at the time was trying to rid itself of its reputation for wickedness [6]. With that, the Walt Disney Company penetrated the U.S. entertainment industry and positioned itself for additional growth through product development, market penetration, diversification, and acquisitions [7]. As of 2022, the company employed 220,000 workers [6] and recorded revenues amounting to 82.7 billion [8].

The following figure 1 shows Disney’s revenues from 2006. The company’s revenue had been growing up until 2020, when it recorded a drop due to the indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 1: Disney’s revenues from 2006 to 2022 [8].

The Table 1 below is the business model initially adopted by Disney in its early years as a cartoon studio.

Table 1: Business model initially adopted by Disney in its early years as a cartoon studio [6].

Key Partners | Film distributor (M.J.Winkler) |

Key Activities | Production of Alice Comedies: filming and animation Continuous technological and artistic improvement |

Key Resources | Start-up capital Secondhand camera Creative capacity |

Value Proposition | Making people happy, through the very best family entertainment |

Customer Relationships | indirect customer relationships/ self-service |

Channels | Film distributor (MJ.Winkler) |

Customer Segments | Broad audiences,younger and elder audiences alike |

Cost Structure | Value-driven cost structure, with profits reinvested in quality improvements |

Revenue Streams | Sales of short films: S 1500 per Alice Comedy |

As the above business model canvas shows, Disney understood its target audience (the family demographic) and leveraged its resources to meet their needs. Today, the company has revised its business model to include outdoor and digital entertainment, all centered around the family unit. The main changes between Disney’s first business model and its present one lies in the diversification of its activities into distinct strategic business units (SBU).

Disney’s current business model has maintained the value proposition it set in the 1920s, but distributed it across SBUs targeted at the outdoor entertainment arena and the digital space. Those SBUs are the Parks, Experiences and Products, Studio Entertainment, Media Networks, and the Direct-to-Consumer and International segments. According to Elberse and Cody, the Studio Entertainment SBU engages in film production through in-house capacities and those acquired through the acquisition of prominent film producers like Pixar, Marvel, and 20th Century Fox. The Studio Entertainment SBU has a direct relationship with the outdoor entertainment industry. The Media Networks SBU comprises the company’s television networks and their related activities. The Direct-to-Consumer and International SBU, the newest addition to the company’s business model, focuses on producing digital entertainment content for a global audience. The Parks, Experiences and Products SBU controls the Disney theme parks and resorts, its cruise and vacation experiences, and consumer branded products like clothes and video games [9]. It is the latter segment, the Parks, Experiences and Products SBU, that suffered the most significant negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic due to its direct relationship with the tourism sector. In contrast, the Direct-to-Consumer and International SBU benefited from the pandemic due to consumer behaviors that shifted entertainment consumption to indoors.

Table 2: Summary of Disney’s current business model [6].

Disney’s Current Business Model | |

Value Proposition | To provide entertainment experiences to the whole family. |

Key Activities | Licensing and merchandizing the brand’s IP. Offering outdoor and travel experiences. Production and distribution of entertainment material. Developing and distributing multi-platform games. |

Key Resources | Network television Innovative technologies in the Parks, Experiences and Products and Studio Entertainment SBUs. IP in the Direct-to-Consumer and International SBU. |

Key Partners | Distributors in the Studio Entertainment SBU, game developers, and third-party entities that license the company’s IP. |

Customer Segments | People of all ages, sports enthusiasts (the Media Networks SBU), and tourists (the Parks, Experiences and Products SBU). |

Customer Relationships | Direct contact through its various SBUs. |

Channels | Television, radio, the internet, and Disney-branded stores. |

Revenue Streams | The Media Networks SBU: Cable-television fees, advertising revenue, and distribution and sales of TV programming. The Parks, Experiences and Products SBU: admission fees, merchandize, accommodation, and food and beverage sales. The Studio Entertainment SBU: revenue from distributing theatrical content, ticket sales, and licensing for live entertainment events. The Direct-to-Consumer and International SBU: subscription fees, selling multi-platform games, merchandizing, and publishing children’s books and other paraphernalia. |

Cost Structure | Costs associated with programming, production, and distribution of entertainment content, labor costs, advertising expenditure, technological innovation costs, production costs for branded merchandize, and other operational expenses for its Parks, Experiences and Products SBU. |

2.2. The COVID-19 Pandemic

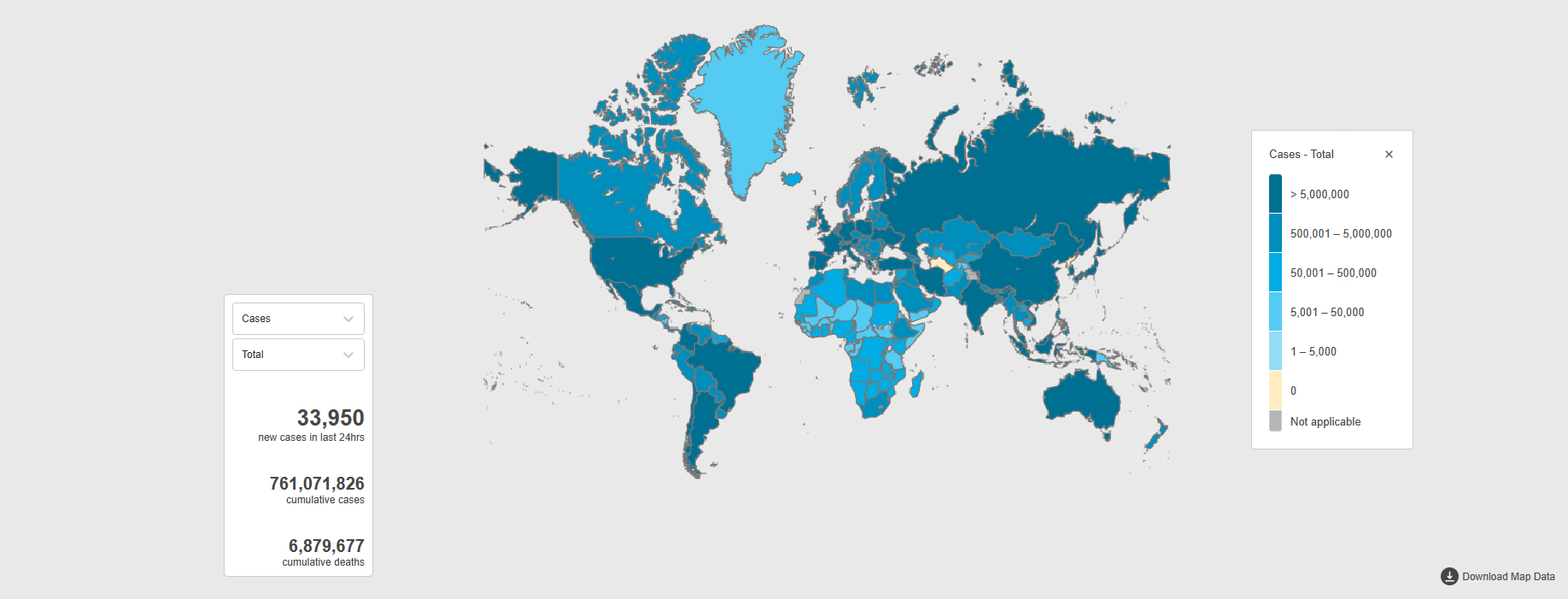

The U.S. ushered the new year in 2020 staring at decisions concerning balancing public health and economic interests, eventually failing at either attempts due to structural deficiencies like an untimely government response and the rapid pace at which the disease was spreading [9]. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a public health emergency on January 30th, 2020 [11] and again a pandemic on March 11th, 2020 [12]. By that time, the disease had spread to several countries, and the world was beginning to understand its severity and witnessing the chaos and havoc it left in each country it spread to. An estimated 121,000 people had been infected by the disease globally, resulting in more than 4,000 deaths, by the time the WHO had declared COVID-19 a pandemic [12]. Today, those numbers stand at more than 755 million infections and close to 7 million deaths [13]. The WHO shows that the majority of infections and deaths are concentrated in developed countries [13]. Bayati suggests that distribution could be due to developed countries’ good data transparency practices, efficient testing and reporting systems, higher population densities in urban areas, and more cross-border transport in developed countries than in developing ones [14]. For instance, the U.S. has reported more than 100 million COVID-19 infections and 1 million deaths since its first recorded case in January 2020, while the entire continent of Africa has reported about 9.4 million infections and 175,000 deaths over the same period [13].

The Figure 2 below by the WHO illustrates the distribution of COVID-19 cases globally. The darker shades represent more reported cases.

Figure 2: Distribution of COVID-19 cases globally [13].

However, the discrepancy in official statistics has not downplayed the severity of the disease since all countries have been impacted by the pandemic in various ways. Among the widely shared impacts have been on economic sectors, with specific industries like tourism and entertainment suffering grave consequences. Thus, companies like Disney that rely on the two sectors were exposed to turbulence as consumer activity slowed in the tourism and entertainment industries in 2020. As such, it is crucial to understand the effect that the pandemic had on the two sectors before examining the impact it had on Disney.

3. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Disney

Understanding the specific impacts that the pandemic had on Disney requires an analysis of the effect it had on the tourism and entertainment sectors. That is because Disney operates as distinct business units that rely on the tourism and entertainment sectors. Thus, when the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the tourism and entertainment industries—two sectors upon which Disney relies for income—the company lost revenue as some of its valuable business segments struggled to reach their customers.

3.1. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Tourism

The declaration of COVID-19 as a pandemic by the WHO caused aftershocks that manifested in global economic activities. Kopecki et al. report that health experts acknowledged that declaring a pandemic carried political and economic ramifications because it risked triggering mitigation measures that could have weakened other vital societal systems [12]. In the case of COVID-19, preventative measures adopted by countries globally included movement restrictions popularly termed ‘lockdowns’, restrictions on international travel, and public health policies requiring specific behaviors like wearing a mask outdoors. Overall, the International Monetary Fund ( IMF) reports that the global economy contracted by 3.5% in 2020 due to COVID-19-related effects [15]. In the U.S., small businesses suffered unprecedented closures in 2020 [16]; and the service industry, which employs close to 80% of Americans, came to a near halt [17]. Among the most impacted stakeholders of the service industry were those working in the tourism and entertainment sectors due to their susceptibility to consumer behavior.

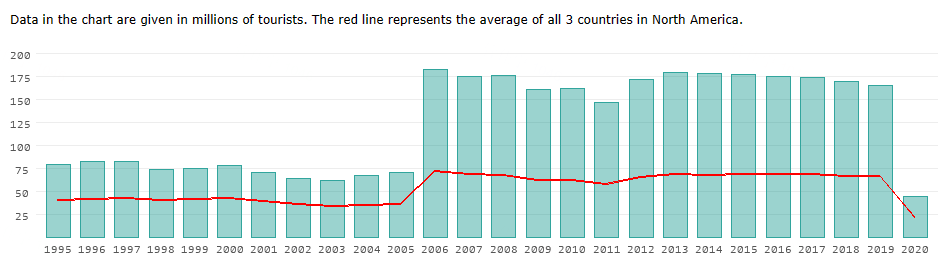

According to Behsudi, tourism accounted for 10% of the global GDP prior to the pandemic and employed 320 million people globally [18]. Statista reports that global tourist numbers fell from a high of about 1.4 billion arrivals in 2019 to 409 million in 2020, representing a 72% decrease [19]. WorldData reports that U.S. arrivals fell from a high of 165 million visitors in 2019 to 45 million in 2020 [20].

Below is a chart from WorldData demonstrating the change in tourist numbers in the U.S. over time. 2020 recorded the lowest numbers since 1995.

Figure 3: The change in tourist numbers in the U.S. over time [20].

Notably, the Figure 3 shows that the COVID-19 pandemic had a larger impact on tourism than the SARS outbreak of 2003 and the global financial crisis of 2009. The World Economic Forum (WEF) estimates that the 2003 SARS epidemic and 2009 financial crisis reduced tourist arrivals by 2 million and 37 million, respectively, demonstrating the severe impact that the COVID-19 pandemic had on the sector [21].

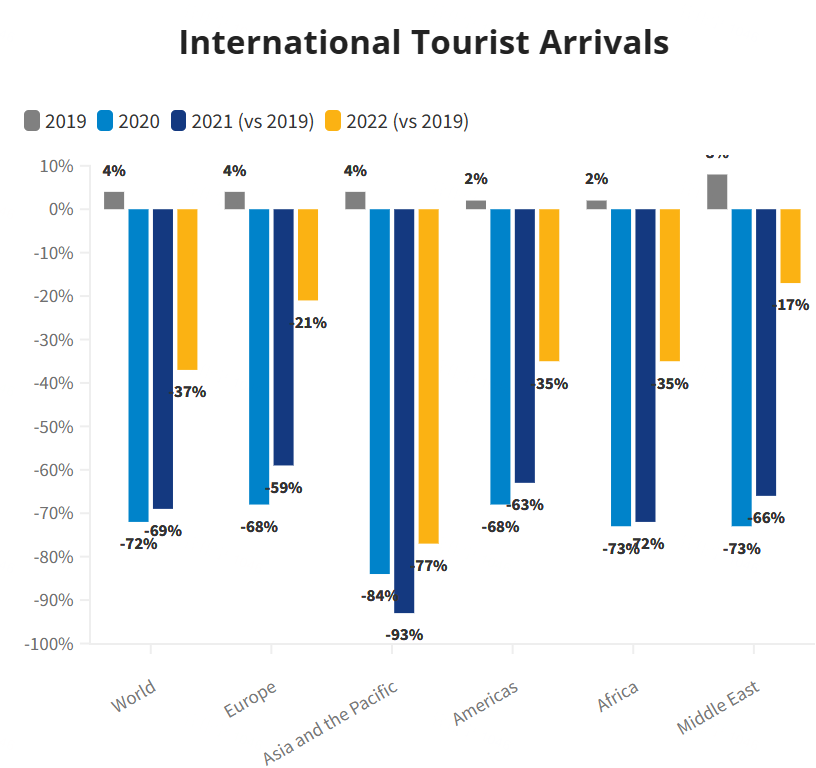

The following chart(Figure 4) from the United Nations’ World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) illustrates the global change in tourism numbers between 2019 and 2020 and the subsequent recovery in 2021 and beyond.

Figure 4: Change in global tourism numbers from 2019 to 2021 [22].

According to Uğur and Akbıyık, tourism is susceptible to changes in the environment and society due to interrelationships between those domains and travelers [11]. Technological changes had significant impacts on the sector since they caused changes in consumer behavior, such as allowing consumers to shelter-in-place without compromising on human experiences like travel and socialization through video-conferencing tools [2]. Disney found itself in a precarious position because some of its core business units rely on tourism for their profitability.

3.2. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Entertainment Sector

Although the global entertainment sector suffered significant negative effects during the pandemic, the impacts were less severe than those witnessed in the tourism industry. Adgate reports that global entertainment revenues in 2020 amounted to 80.8 billion, representing an 18% decrease from 2019 figures, and being the lowest figure since 2016 [23]. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic varied according to segment. Those reliant on human traffic, such as theatrical performances, faced more challenges than those that relied on digital services, such as streaming solutions [23]. Such distributed effects resulted in varied impacts on Disney, a company that operates businesses reliant on outdoor and digital entertainment solutions.

3.3. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Disney

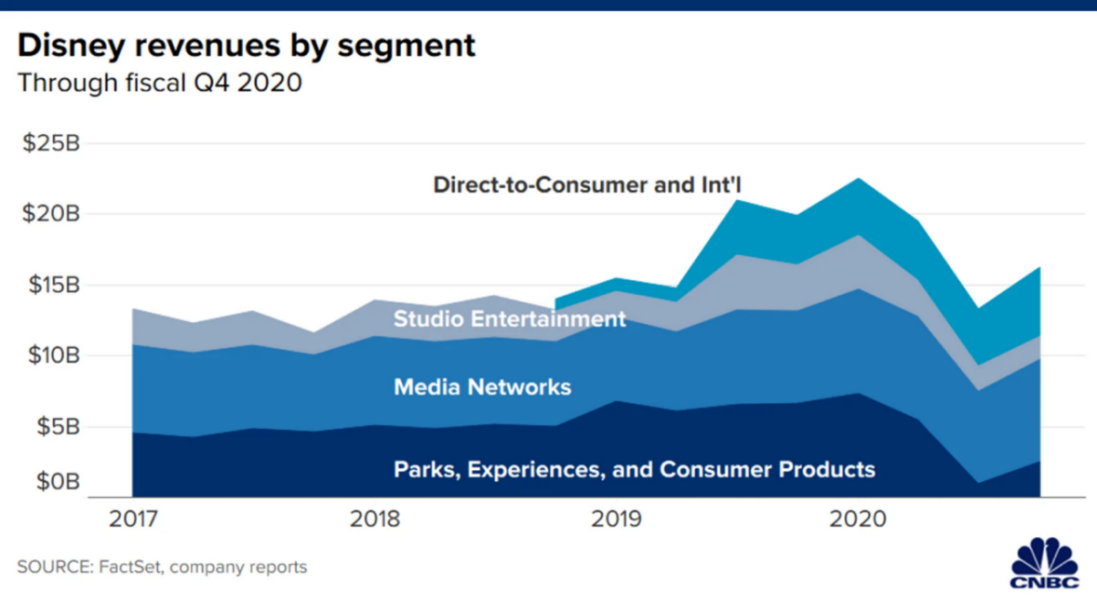

As illustrated in previous sections, the COVID-19 pandemic had deleterious effects on the tourism and entertainment sectors—the two industries upon which Disney relies for its success. Still, its SBUs performed differently based on their ability to respond to environmental changes. The Parks, Experiences and Products SBU is intertwined with the tourism sector, such that any negative change in the industry resulted in poor performance for the segment. According to Whitten, the Parks, Experiences and Products SBU is Disney’s third largest source of revenue, accounting for 37% of its $69.6 income in 2019 [24]. The SBU’s most visible offering is the Disney theme parks distributed globally. The SBU lost about $3.5 billion due to movement restrictions imposed within the U.S. and by other countries [24]. That loss represented a 61% decrease in revenue for the SBU, which led to the termination of 28,000 workers in 2020 [24]. A notable observation is that the SBU’s losses seemed to follow the 68% drop in tourism numbers in the Americas, as seen in Figure 3. Thus, one would infer that a change in tourist activities would lead to an increase in the SBU’s performance as long as other influences, like movement restrictions, are not imposed.

In the entertainment sector, Disney suffered a loss in revenue at its Studio Entertainment SBU. Specifically, the SBU’s revenue was $1.6 billion in 2020, a decrease of 52% compared to 2019 [25]. The SBU’s losses were consistent with the negative trends witnessed in the entertainment industry. For instance, as captured in previous sections, theatrical performances were halted for most of the year in 2020 due to the pandemic [23]. As such, Disney’s Studio Entertainment SBU could neither sell tickets to live theatrical performances nor produce theatrical content for consumption via its cable networks [25].

The underperformance of the Parks, Experiences and Products and Studio Entertainment SBUs meant that Disney could not fulfill its commercial goal of distributing its experiences to a large audience. At the same time, the world’s reliance on technology during the pandemic altered consumer behaviors in ways that harmed the Parks, Experiences and Products and Studio Entertainment SBUs by facilitating shelter-in-place trends throughout the year. However, technology improved the performance of Disney’s SBUs that relied on digital services. One such SBU is the Direct-to-Consumer and International segment.

Disney’s Direct-to-Consumer and International business was among the company’s best performing SBUs in 2020. Feiner and Whitten report that the SBU increased its revenues by 41% during the pandemic, primarily due to the Disney+ streaming service [25]. Launched in 2019 as a direct response to the rise of video on-demand services like Netflix, Disney+ boasts more than 164 million subscribers and offers family-friendly content that continues to strengthen Disney’s brand recognition and loyalty among customers [9, 26].

Below is a chart presenting the performance of Disney’s SBUs in 2020. The chart shows the positive performance of the Direct-to-Consumer and International SBUs since 2019, when the company launched the Disney+ streaming service.

Figure 5: The performance of Disney’s SBUs in 2020 [25].

Part of the Direct-to-Consumer and International SBU’s stellar performance has been its data-driven customer segmentation—defined as “an approach for separating an overall customer population based on segment differences defined by a specific set of attributes” that allows it to target audiences with relevant content [27]. The subsequent months following Disney+’s launch included consolidating the company’s wide array of original titles-sorted by customer segments-to form a formidable entertainment database that threatened streaming incumbents like Netflix.

Soares et al. note that, unlike Netflix, Disney has a strong brand recognition, loyalty, and association with quality and nostalgia that draws audiences to its content [28]. Elberse and Cody suggest that Disney is regarded as a primary outlet for children’s contents, which incentivizes families to sign up to Disney+ [9]. It is no wonder, then, that the Disney+ streaming service experienced growth during the pandemic. Moreover, the company spent 80% of its 2020 advertising budget popularizing the streaming service across all major social media platforms [28]. Consequently, Disney managed to align the Direct-to-Consumer and International SBUs with the changes in consumer behaviors in 2020 (staying home and relying on technology).

4. Recommendations

Considering the negative impacts the pandemic had on tourism and the entertainment sectors, and the success of Disney’s Direct-to-Consumer and International SBUs, the present study recommends business model adaptation (BMA) as a viable business strategy for Disney in the post-pandemic world. Business model adaptation involves applying emergent technologies to a firm’s core capabilities in ways that guarantee competitiveness [3]. It can improve value creation, capture new customers, disrupt existing markets, or define new markets for young and established companies [3], meaning that it can be leveraged to help companies respond to external shocks like the COVID-19 pandemic.

In context of Disney, BMA can entail focusing on growing its digital services in the coming years. That means limiting expenditures on SBUs that rely on industry trends for their performance, such as the Parks, Experiences and Products and Studio Entertainment SBUs that depend on tourism and outdoor entertainment. Sheth notes that consumer behaviors are determined by social contexts (marriage, travel, and any other life-altering events), technologies that modify people’s habits, rules and regulations, and unpredictable occurrences like the COVID-19 pandemic [2]. Once new behaviors are learnt and they prove more convenient than prior ones, new consumer trends are established [2]. The COVID-19 pandemic is a unique event because it combined all 4 sources of consumer behaviors and ushered convenient solutions like streaming content at home and sharing virtual experiences through video conferencing technologies. Thus, even though the UNWTO reports an increase in tourist arrivals globally from 2021 onwards (Figure 4) [22], there is a strong likelihood that consumers will increasingly rely on digital entertainment solutions and less on travel. In that regard, BMA can help Disney to channel its agility and innovations toward strengthen aspects of its business models that proved resilient to the pandemic, such as the Direct-to-Consumer and International SBUs.

Moreover, Disney anticipates its streaming service will have 260 million paying subscribers by 2024; Netflix currently caters to 231 million subscribers globally [29], placing it firmly within Disney+’s subscriber goals for 2024. Additionally, Netflix spends more on content than Disney+ because, unlike Disney, it licenses most of its content from IP holders, while Disney owns most of the IP behind its movies due to acquisitions of franchises like Marvel’s Avengers [9]. Therefore, Disney+ can charge cheaper subscription fees than Netflix without hurting its bottom line. Considering such realities, it would be strategically advantageous for Disney to focus on growing its Direct-to-Consumer and International SBUs while limiting its exposure to environmental forces in its other SBUs.

To test the viability of its SBUs, Disney can use tools like the GE Matrix that help to “develop a strategy to identify SBUs that should be prioritized in investment and growth strategies, and to review SBUs that should no longer be retained” [30]. The GE Matrix quantifies two factors relevant to business strategy development: the attractiveness of an industry and an SBU’s competitiveness in that industry [30]. Its vertical axis measures industry attractiveness and relies on attributes such as “market growth rate, market size, industry profitability, industry rivalry, and global opportunities” [30]. The horizontal axis examines SBU viability using factors like “market share, growth rate, brand equity, channel equity, and profitability” [30]. The resulting GE Matrix comprises 3 major segments that inform SBU with the highest attractiveness.

Table 3: An example of the GE Matrix [30].

Business Unit Attractiveness | ||||

High | Medium | Low | ||

Industry Attractiveness | High | 1 | 3 | 6 |

Medium | 2 | 5 | 8 | |

Low | 4 | 7 | 9 | |

As Table 3 shows, the GE Matrix results in a 9-cell table grouped into 3 major segments labeled high, medium, and low. According to Sood, Cells 1-3 characterize the first segment and reflect a strong SBU in an attractive market. Cells 4-6 account for second segment and represent “SBUs with medium attractiveness either because the firm has strong SBUs in an unattractive market or weak SBUs in an attractive industry”. Cells 7-9 are the third segment and comprise weak SBUs in undesirable markets [30]. Thus, Disney can utilize tools like the GE Matrix to validate the decision to grow their Direct-to-Consumer and International SBU.

5. Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic occasioned unprecedented effects that rippled throughout the world’s economic sectors. The tourism and entertainment industries suffered significant losses in revenue due to reduced travel in the wake of movement restrictions globally. Consequently, businesses that had been reliant on the two sectors experienced difficulties in 2020, among them Disney. Disney’s connection to the tourism and entertainment industries lies in business units like the Parks, Experiences and Products and Studio Entertainment SBUs. The two SBUs are dependent upon the performance of the tourism and outdoor entertainment industries and as such, suffered losses throughout 2020. In contrast, the Direct-to-Consumer and International SBU increased its revenues due to changing consumer habits that encouraged people to stay indoors. Therefore, minding the effect the pandemic had on its business units, the present paper recommends that Disney should focus its investments on the Direct-to-Consumer and International SBU. Doing so will allow it to position itself in an area that will likely experience growth even in times of uncertainties like the COVID-19 pandemic.

The main limitation the present study faced was the lack of access to primary resources such as Disney’s executives and representatives in the tourism and entertainment sectors. Consequently, the study relied on secondary information that is prone to bias, inaccuracies, and irrelevance—for instance, much of the data on tourism and entertainment was produced in 2020 and 2021. Moreover, business strategies are dependent on localized contexts like a company’s timely growth strategies. Thus, the present paper leaves room for future research founded on primary information that best reflects information accuracy and currency, and organizational realities and strategies.

References

[1]. Anderson, C., Bieck, C., & Marshall, A. (2020). How business is adapting to COVID-19: Executive insights reveal post-pandemic opportunities. Strategy & Leadership, 49(1), 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1108/sl-11-2020-0140

[2]. Sheth, J. (2020). Impact of covid-19 on consumer behavior: Will the old habits return or die? Journal of Business Research, 117, 280–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.059

[3]. Peñarroya-Farell, M., & Miralles, F. (2021). Business Model Dynamics from interaction with open innovation. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 7(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7010081

[4]. Teece, D., Peteraf, M., & Leih, S. (2016). Dynamic capabilities and organizational agility: Risk, uncertainty, and strategy in the Innovation Economy. California Management Review, 58(4), 13–35. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2016.58.4.13

[5]. Ebersberger, B., & Kuckertz, A. (2021). Hop to it! the impact of organization type on innovation response time to the COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Business Research, 124, 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.11.051

[6]. Voigt, K.-I., Buliga, O., & Michl, K. (2016). Making people happy: The case of the walt disney company. Management for Professionals, 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-38845-8_10

[7]. Isidore, C. (2023, February 9). Disney plans to cut 7,000 jobs and reward shareholders | CNN business. CNN. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://edition.cnn.com/2023/02/08/business/disney-earnings/index.html

[8]. Guttmann, A. (2023, January 5). The Walt Disney Company: Global revenue 2006-2022. Statista. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/273555/global-revenue-of-the-walt-disney-company/

[9]. Elberse, A., & Cody, M. (2020). The Video-Streaming Wars in 2019: Can Disney Catch Netflix? Harvard Business School, Case 9-519-094.

[10]. Yong, S. by E. (2020, August 6). How the Pandemic Defeated America. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/09/coronavirus-american-failure/614191/

[11]. Uğur, N. G., & Akbıyık, A. (2020). Impacts of COVID-19 on Global Tourism Industry: A cross-regional comparison. Tourism Management Perspectives, 36, 100744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100744

[12]. Kopecki, D., Lovelace Jr., B., Feuer, W., & Higgins-Dunn, N. (2020, March 12). World Health Organization declares the coronavirus outbreak a global pandemic. CNBC. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/11/who-declares-the-coronavirus-outbreak-a-global-pandemic.html

[13]. WHO. (2023). Who coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. World Health Organization. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://covid19.who.int/

[14]. Bayati, M. (2021). Why is covid-19 more concentrated in countries with high economic status? Iranian Journal of Public Health. https://doi.org/10.18502/ijph.v50i9.7081

[15]. IMF. (2021, January 1). World economic outlook update, January 2021: Policy Support and vaccines expected to lift activity. IMF. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2021/01/26/2021-world-economic-outlook-update

[16]. Irwin, N. (2020, May 11). Why Economic Pain Could Persist Even After the Pandemic Is Contained. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/11/upshot/virus-lasting-economic-effects.html.

[17]. Orrell, B., Bishop, M., & Hawkins, J. (2020). (Rep.). A road map to reemployment in the COVID-19 economy: Empowering workers, employers, and states. American Enterprise Institute. doi:10.2307/resrep25357

[18]. Behsudi, A. (2020). Tourism-dependent economies are among those harmed the most by the pandemic. IMF. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2020/12/impact-of-the-pandemic-on-tourism-behsudi

[19]. Statista. (2023, February 2). Covid-19: Change in international tourist arrivals worldwide 2022. Statista. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1109763/coronavirus-international-tourist-arrivals/

[20]. WorldData. (n.d.). Tourism development in the United States of America. Worlddata.info. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.worlddata.info/america/usa/tourism.php

[21]. WEF. (2022). International travel levels tipped to soar again in 2022. World Economic Forum. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/06/international-travel-2022-covid19-tourism/

[22]. UNWTO. (2022, September 26). World Tourism Organization. International Tourism Back to 60% of Pre-Pandemic Levels in January-July 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.unwto.org/news/international-tourism-back-to-60-of-pre-pandemic-levels-in-january-july-2022

[23]. Adgate, B. (2022, November 9). The impact covid-19 had on the entertainment industry in 2020. Forbes. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/bradadgate/2021/04/13/the-impact-covid-19-had-on-the-entertainment-industry-in-2020/?sh=294f1ff250f0

[24]. Whitten, S. (2020, September 30). Disney to lay off 28,000 employees as coronavirus slams its theme park business. CNBC. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.cnbc.com/2020/09/29/disney-to-layoff-28000-employees-as-coronavirus-slams-theme-park-business.html

[25]. Feiner, L., & Whittej, S. (2020, November 12). Disney shares rise after reporting 73 million paid disney+ subscribers, losses not as drastic as expected. CNBC. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.cnbc.com/2020/11/12/disney-dis-q4-2020-earnings.html

[26]. The Walt Disney Company. (2022). (rep.). The Walt Disney Company Reports Fourth Quarter And Full Year Earnings for Fiscal 2022. The Walt Disney Company.

[27]. An, J., Kwak, H., Jung, S.-gyo, Salminen, J., & Jansen, B. J. (2018). Customer segmentation using online platforms: Isolating behavioral and demographic segments for persona creation via Aggregated User Data. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-018-0531-0

[28]. Soares, D., Freitas, H., Oliveira, J., Vieira, L., & Au-Yong-Oliveira, M. (2022). Keeping the eyes busy: A case study of disney+. Information Systems and Technologies, 195–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04819-7_21

[29]. Stoll, J. (2023, January 20). Netflix: Number of subscribers worldwide 2022. Statista. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/250934/quarterly-number-of-netflix-streaming-subscribers-worldwide/#:~:text=Netflix%20had%20nearly%20231%20million,compared%20with%20the%20previous%20quarter.

[30]. Sood, A. (2010). GE/McKinsey Matrix. Wiley International Encyclopedia of Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444316568.wiem05040

Cite this article

Feng,Z. (2023). The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Walt Disney Company. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,22,198-208.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Management Research and Economic Development

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Anderson, C., Bieck, C., & Marshall, A. (2020). How business is adapting to COVID-19: Executive insights reveal post-pandemic opportunities. Strategy & Leadership, 49(1), 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1108/sl-11-2020-0140

[2]. Sheth, J. (2020). Impact of covid-19 on consumer behavior: Will the old habits return or die? Journal of Business Research, 117, 280–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.059

[3]. Peñarroya-Farell, M., & Miralles, F. (2021). Business Model Dynamics from interaction with open innovation. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 7(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7010081

[4]. Teece, D., Peteraf, M., & Leih, S. (2016). Dynamic capabilities and organizational agility: Risk, uncertainty, and strategy in the Innovation Economy. California Management Review, 58(4), 13–35. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2016.58.4.13

[5]. Ebersberger, B., & Kuckertz, A. (2021). Hop to it! the impact of organization type on innovation response time to the COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Business Research, 124, 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.11.051

[6]. Voigt, K.-I., Buliga, O., & Michl, K. (2016). Making people happy: The case of the walt disney company. Management for Professionals, 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-38845-8_10

[7]. Isidore, C. (2023, February 9). Disney plans to cut 7,000 jobs and reward shareholders | CNN business. CNN. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://edition.cnn.com/2023/02/08/business/disney-earnings/index.html

[8]. Guttmann, A. (2023, January 5). The Walt Disney Company: Global revenue 2006-2022. Statista. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/273555/global-revenue-of-the-walt-disney-company/

[9]. Elberse, A., & Cody, M. (2020). The Video-Streaming Wars in 2019: Can Disney Catch Netflix? Harvard Business School, Case 9-519-094.

[10]. Yong, S. by E. (2020, August 6). How the Pandemic Defeated America. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/09/coronavirus-american-failure/614191/

[11]. Uğur, N. G., & Akbıyık, A. (2020). Impacts of COVID-19 on Global Tourism Industry: A cross-regional comparison. Tourism Management Perspectives, 36, 100744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100744

[12]. Kopecki, D., Lovelace Jr., B., Feuer, W., & Higgins-Dunn, N. (2020, March 12). World Health Organization declares the coronavirus outbreak a global pandemic. CNBC. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/11/who-declares-the-coronavirus-outbreak-a-global-pandemic.html

[13]. WHO. (2023). Who coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. World Health Organization. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://covid19.who.int/

[14]. Bayati, M. (2021). Why is covid-19 more concentrated in countries with high economic status? Iranian Journal of Public Health. https://doi.org/10.18502/ijph.v50i9.7081

[15]. IMF. (2021, January 1). World economic outlook update, January 2021: Policy Support and vaccines expected to lift activity. IMF. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2021/01/26/2021-world-economic-outlook-update

[16]. Irwin, N. (2020, May 11). Why Economic Pain Could Persist Even After the Pandemic Is Contained. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/11/upshot/virus-lasting-economic-effects.html.

[17]. Orrell, B., Bishop, M., & Hawkins, J. (2020). (Rep.). A road map to reemployment in the COVID-19 economy: Empowering workers, employers, and states. American Enterprise Institute. doi:10.2307/resrep25357

[18]. Behsudi, A. (2020). Tourism-dependent economies are among those harmed the most by the pandemic. IMF. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2020/12/impact-of-the-pandemic-on-tourism-behsudi

[19]. Statista. (2023, February 2). Covid-19: Change in international tourist arrivals worldwide 2022. Statista. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1109763/coronavirus-international-tourist-arrivals/

[20]. WorldData. (n.d.). Tourism development in the United States of America. Worlddata.info. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.worlddata.info/america/usa/tourism.php

[21]. WEF. (2022). International travel levels tipped to soar again in 2022. World Economic Forum. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/06/international-travel-2022-covid19-tourism/

[22]. UNWTO. (2022, September 26). World Tourism Organization. International Tourism Back to 60% of Pre-Pandemic Levels in January-July 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.unwto.org/news/international-tourism-back-to-60-of-pre-pandemic-levels-in-january-july-2022

[23]. Adgate, B. (2022, November 9). The impact covid-19 had on the entertainment industry in 2020. Forbes. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/bradadgate/2021/04/13/the-impact-covid-19-had-on-the-entertainment-industry-in-2020/?sh=294f1ff250f0

[24]. Whitten, S. (2020, September 30). Disney to lay off 28,000 employees as coronavirus slams its theme park business. CNBC. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.cnbc.com/2020/09/29/disney-to-layoff-28000-employees-as-coronavirus-slams-theme-park-business.html

[25]. Feiner, L., & Whittej, S. (2020, November 12). Disney shares rise after reporting 73 million paid disney+ subscribers, losses not as drastic as expected. CNBC. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.cnbc.com/2020/11/12/disney-dis-q4-2020-earnings.html

[26]. The Walt Disney Company. (2022). (rep.). The Walt Disney Company Reports Fourth Quarter And Full Year Earnings for Fiscal 2022. The Walt Disney Company.

[27]. An, J., Kwak, H., Jung, S.-gyo, Salminen, J., & Jansen, B. J. (2018). Customer segmentation using online platforms: Isolating behavioral and demographic segments for persona creation via Aggregated User Data. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-018-0531-0

[28]. Soares, D., Freitas, H., Oliveira, J., Vieira, L., & Au-Yong-Oliveira, M. (2022). Keeping the eyes busy: A case study of disney+. Information Systems and Technologies, 195–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04819-7_21

[29]. Stoll, J. (2023, January 20). Netflix: Number of subscribers worldwide 2022. Statista. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/250934/quarterly-number-of-netflix-streaming-subscribers-worldwide/#:~:text=Netflix%20had%20nearly%20231%20million,compared%20with%20the%20previous%20quarter.

[30]. Sood, A. (2010). GE/McKinsey Matrix. Wiley International Encyclopedia of Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444316568.wiem05040