1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background and Significance

The COVID-19 pandemic has unleashed an unprecedented wave of challenges and disruptions across the globe, necessitating significant investments by governments to combat its impact. The US government, in particular, has paid a high cost by enacting four major emergency legislation in response to the pandemic. These measures aimed not only to address the immediate health crisis but also to support and revive the faltering economy. The first piece of emergency legislation, signed into law on March 6, authorized the allocation of 8 billion USD [1]. Of this amount, 36% was designated for intergovernmental fees. At the same time, the remaining funds were dedicated to support state and municipal governments' instantaneous public health needs as well as vaccine development and research efforts [1]. Shortly after that, on March 18, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act was enacted, allocating a substantial sum of 192 billion USD in spending [1]. However, the largest response to the crisis came from the Relief, Coronavirus Aid, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, which amounted to a staggering 2.7 trillion USD [1].

The enactment of these emergency legislations demonstrates the government's commitment to combating the multifaceted challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. By allocating substantial financial resources, the US government addresses the immediate health needs of the population during these uncertain times. Meanwhile, the government highlights the significance of the pandemic, and the urge to control it, due to its severe negative effect brought to society.

The unemployment rate is one of the most obvious factors that is affected by this global crisis, causing a crucial social cost for the whole society. The United States, in particular, witnessed a significant rise in its unemployment rate on April 2020 as a direct consequence of the pandemic. Prolonged unemployment can have detrimental effects on individuals' mental health and physical wellness. The stress, anxiety, and feelings of hopelessness associated with unemployment can lead to increased rates of substance misuse, depression, and other psychological challenges. Furthermore, the unequal working environment and the skewed resources can cause more harmful effects on less-fortunate individuals, further aggravating the existed social inequality.

1.2. Literature review

Academics have realized the long-lasting effect of the COVID-19 pandemic. Particularly, the psychological loss experienced by the population due to the widespread job losses caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting anxiety, a sense of existential loss, and intense fear [2]. Job is closely related to both people's basic needs, especially for the less fortunate people; they require their income to buy necessities. Meanwhile, the job is also related to human needs that are in the higher hierarchy of needs, such as social bonding, social contribution, and self-actualization [2]. Consequently, the impact of job loss is linked to significant psychological stress, as it carries societal judgments and fosters feelings of insecurity, anxiety, and embarrassment [3]. Considering the high cost of mental health treatment, it makes the less fortunate people fall into a poverty cycle, further exacerbating the existing inequality. Unlike other job losses in history, the high unemployment rate under the pandemic has had a long-lasting effect on the labor force participation rate. Under the special restrictions, due to shelter-in-place restrictions, certain laid-off workers may face limitations in actively seeking new employment, leading to their exclusion from the labor force count rather than being classified as unemployed [4]. Eight million workers left the labor force in March and April due to various reasons, leading to a drop in the labor participation rate from 63.4% in February 2020 to 60.2% in April 2020, reaching its lowest level since the early 1970s [5,6]. Workers, including those at the forefront during the pandemic, refuse to settle for substandard employment opportunities. Low wages mark these jobs, unfavorable working conditions such as irregular shifts, health hazards, physically demanding tasks, and inadequate social benefits [6].

1.3. Research Contents and Framework

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted economies and societies worldwide, and the United States has not been immune to its pervasive effects and will continue to suffer in the recent future. As the virus continues to sweep through the nation, the labor market has experienced significant upheavals, leading to widespread job losses and financial uncertainty for millions of workers. By closely focusing on the changes happening in the US, including but not limited to the labor market shifts, this essay intends to analyze the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on the US unemployment rate, examining the possible inequalities that will be caused by the labor market structural change, the physical and psychological inequalities faced by individuals and the economy, and potential long-term suggestions for the US governments that closely target these areas. In particular, under this special period, government interventions such as introducing job training programs, expanding healthcare insurance coverage, and providing higher unemployment benefits are needed. These suggestions can effectively alleviate the inequality brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic while mitigating the existing social inequality. By delving into these aspects and providing effective suggestions, a comprehensive understanding of the pandemic's impact on the employment situation in the United States will be gained, shedding light on the magnitude of the crisis and the significance of effective policy responses.

2. Case Description

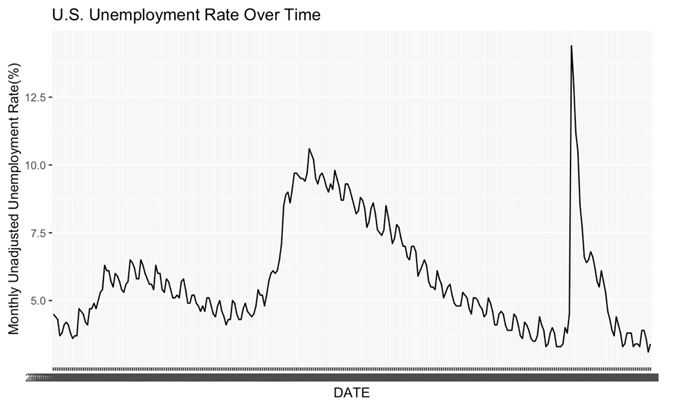

Against the backdrop of global crises such as COVID-19 and other recent pandemics, the US unemployment rate has been profoundly affected. In December 2019, a pneumonia outbreak with an unknown source was first observed in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China [7]. The World Health Organization officially designated it as a pandemic on March 12, 2020, owing to the extensive spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and the considerable number of deaths attributed to COVID-19 [7]. Globalization, in particular, has accelerated communication between countries, facilitating the rapid global spread of the virus. The toll of this epidemic has been significant worldwide, resulting in loss of human lives, adverse economic effects, and increased poverty, with the US alone witnessing over 200,000 deaths [7, 8]. In response to this global situation, governments have implemented restrictions and lockdowns to protect citizens. In April 2020, these measures impacted nearly the entire population of the United States [9]. A visual representation of the data highlights a conspicuous peak in April 2020, with the unemployment rate reaching 14.4%. Figure 1 stands in contrast to the pre-COVID-19 peak of around 11%. Simultaneously, labor demand was substantially declining, which plummeted by 44% between February and April 2020 [9]. Temporary layoffs accounted for 75% of the increase in unemployment [9]. Within the initial weeks of the shutdown, approximately 33.5 million individuals, constituting 20% of the labor force, applied for unemployment benefits [6]. These figures demonstrate a clear positive correlation between the US unemployment rate and the COVID-19 pandemic. It is crucial to recognize the critical role played by the unemployment rate, as it has far-reaching implications for societal issues such as inequality, purchasing power, and inflation. Policymakers will face significant challenges in addressing these consequences.

Figure 1: Monthly (Not Seasonally Adjusted) Unemployment Rate From 2000-2023.

3. Analysis of the Problem

3.1. Labor Structure Changes Under the COVID-19

The elevated unemployment rate amidst the global background of the Covid-19 pandemic highlights a significant likelihood of increasing inequality. This, in turn, can lead to a cascade of societal consequences, including higher crime rates, diminished public health, and reduced economic growth. Many companies have transitioned to remote or hybrid working modes throughout the pandemic-affected years. However, two distinct working experiences have emerged during the Covid-19 pandemic. One experience is shared by individuals in higher-paying and high-skilled jobs. Due to the flexibility and minimal work venue requirements of these positions, they have been able to adapt more easily to the labor market's structural changes. On the other hand, the majority of the working population, particularly those unable to work from home, face significant challenges. They are exposed to daily risks, experiencing job losses or reductions and are burdened with concerns about contracting the virus while also struggling to meet their basic needs [10]. Moreover, it is worth noting that the individuals least likely to have the opportunity to adapt to the new working mode are those with lower wages. While three-quarters of the highest-earning 20% of workers can at home, fewer than one in twenty of the lowest-earning 20% enjoy such privileges [11]. Consequently, low-wage and face-to-face jobs have suffered disproportionate employment losses [9].

3.2. The Physical Burden: Exacerbating Inequality

In the midst of the COVID-19 threat, people's lives have become more vulnerable, leading to higher health costs and further widening the income inequality gap that already existed prior to the crisis [10]. Notably, the expenses associated with COVID-19 treatment pose a significant burden on individuals with lower incomes. When considering only the costs incurred during the course of the infection, the median medical cost amounts to $3,045 [12]. However, when accounting for additional expenses such as outpatient visits and rehospitalization that may arise after the infection, the total cost rises to $3,994 [12]. Moreover, COVID-19 symptoms can lead to long-term health sequela, necessitating further medical expenditures. As a result, the actual costs incurred can far exceed the aforementioned figures. To put these costs into perspective, it is worth considering the adjusted US tax bracket for 2023, where the bottom bracket is set at 10% for single individuals with annual incomes of $11,000 [13]. In this scenario, the health costs associated with COVID-19 treatment account for a staggering 36.3% of the income of low-wage workers. This places an enormous strain on their living standards, particularly considering that lower-wage individuals are less adaptable to the structural changes occurring in the labor market, increasing inequality.

3.3. The Psychological Burden: Exacerbating Inequality

Besides the direct health costs, the COVID-19 crisis has had significant psychological implications. Residing in an unpredictable society and confronting the persistent possibility of job insecurity, individuals are subjected to unstable employment conditions, ongoing uncertainty, and persistent stress, Exposing them to potential physical, mental health, and relational adversities [10]. Government quarantine policies further exacerbate this situation. Individuals being restricted to lockdown measures are more likely to experience a lack of interest, heightened worry, and depression each day, with increases of 0.8, 0.5, and 0.8 percentage points, respectively [8]. Similarly, low-paid workers are particularly vulnerable to these psychological health costs. Workers in occupations that cannot be performed remotely, such as those in the hotel industry, catering, manufacturing, merchandising, and construction, have experienced the greatest increase in psychological distress [14]. Simultaneously, a significant proportion of the US labor force, around 75%, is engaged in these types of occupations that typically offer lower wages [14]. Moreover, the existing inequalities that were present prior to the pandemic are exacerbated by the current crisis. Employment and income losses, coupled with the related psychological impacts, have disproportionately affected groups that were already suffering from inequality before the pandemic [14]. The financial burden of seeking mental health treatment further deepens income inequality, potentially eroding social cohesion.

4. Suggestions

Considering the high unemployment rate resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on labor market structure, along with the significant physical and mental health costs that will accentuate societal inequality, the following suggestions were proposed aiming to address these issues in future circumstances [15].

4.1. Promoting Remote Work as a Path to Reduce Income Inequality

To assist low-wage workers in adapting to structural changes, the US government should prioritize providing labor training programs that facilitate the transition from conventional work modes to online work. Working from home plays a crucial role in reducing income inequality as it helps protect workers from on-site virus exposure. This flexible working arrangement has demonstrated its significance in developed societies as a viable solution to coexist with the COVID-19 virus. It enables work continuity while adhering to social distancing measures, an important solution in developed societies. Encouraging face-to-face workers to shift to remote work can also contribute to mitigating income inequality. Reports suggest that employees in areas heavily concerned by COVID-19 would benefit more from the increased feasibility of working from home. Additionally, since herd immunity against the coronavirus is not yet achieved, enhancing the feasibility of remote work is a long-term solution. However, it is essential to recognize that while this transition is necessary for vulnerable labor groups, its effectiveness in mitigating income inequality remains uncertain, as it tends to disproportionately benefit male, older, educated, and higher-paid employees, leading to unequal impacts across the labor income distribution.

4.2. Policy Measures for Addressing Health Inequality

The high cost of physical health is another crucial factor exacerbating inequality. Suggestions to alleviate its effects include expanding healthcare insurance coverage to enhance accessibility and reduce out-of-pocket expenses, as well as promoting workforce diversity. Prioritizing equity, collective health, justice, and well-being through local, state, and federal policy interventions will steer society toward a more resilient and equitable future. Furthermore, inclusive policies such as broadening social protection and government programs are essential to ensure the well-being of disadvantaged individuals. The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed deep-rooted social, economic, and political disparities that have long persisted. Even prior to the pandemic, there were already indications of worsening inequalities in various aspects of life, such as the declining life expectancy among the most disadvantaged groups in the UK and the USA. Thus, appropriate public policy responses are crucial in this unique era to prevent the exacerbation of health inequalities in the future.

4.3. Policy Interventation for Addressing Mental Health Inequalities

Considering the psychological burdens imposed by lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is imperative to implement interventions that address mental health issues in conjunction with government measures such as quarantine. The distinct experiences of workers during the pandemic have underscored existing inequalities, necessitating efforts to support and protect the most vulnerable workers and provide them with necessary resources. Promoting fair and inclusive labor practices is also essential. Governments play a pivotal role in implementing supportive policies, such as higher unemployment benefits, expanded financial support for mental health service delivery, and increased awareness of mental health issues. According to research conducted by Donnelly and Farrina, it indicates that implementing supportive social policies can effectively mitigate the connection between income shocks and the deterioration of mental health [14]. In particular, policies need to address housing, food, and employment security to alleviate psychological burdens [8]. Furthermore, targeted focus should be directed towards marginalized groups, such as women and African Americans, to prevent the exacerbation of racial and gender disparities [8]. Within the United States, citizens have access to valuable resources to address their psychological needs through federal agencies like the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). These agencies offer beneficial information about treatment services and mental health care providers [8].

5. Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the crucial need for the US government to carefully evaluate and implement adequate policies to address the challenges posed by labor market structural changes, as well as the physical and psychological burdens experienced by individuals. Data have shown signs of a short-run positive correlation between COVID-19 and the unemployment rate, which will further exacerbate the existing social inequalities and have long-term impacts on people's living quality and basic needs. In order to tackle these problems, it is vital for the US government to play an active role in providing necessary public goods and support to assist those in need.

One crucial step is to prioritize job training programs that facilitate the transition in the labor market structural change. Such programs can equip individuals with the skills needed to adapt to a safer working environment and reduce the impact of unemployment. Additionally, implementing policies that expand healthcare insurance coverage and enhance unemployment benefits can provide significant support in alleviating the physical and psychological burdens faced by individuals.

Monitoring the unemployment rate closely and designing effective strategies to mitigate job losses and promote equitable recovery should be a priority for policymakers. Employers and business leaders also have a role to play in considering the social impact of their decisions during this global crisis. Protecting employees' well-being and exploring alternative measures such as reduced work hours, retraining programs, or remote work options can help minimize job losses and foster a more inclusive workforce.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of this essay in quantitatively measuring the impacts of COVID-19 on the US unemployment rate. Future research could focus on building models and analyzing the quantitative relationships between COVID-19 and other economic indicators such as the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and Gini Coefficient. In addition to these indicators, measuring and predicting the financial cost of the aforementioned government interventions is also significant. By doing so, researchers can gain valuable insights into the impact of people's living conditions during the pandemic and provide reasonable predictions for future indicators, enabling timely and applicable government interventions.

In conclusion, addressing the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic requires comprehensive efforts from the government, employers, and researchers. By implementing the suggested measures and fostering an inclusive and supportive environment, we can work towards mitigating inequality, protecting individuals' well-being, and promoting a more resilient and equitable society.

References

[1]. Holtz, D.,et al. (2020). Interdependence and the cost of uncoordinated responses to COVID-19. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences - PNAS, 117(33), 19837–19843.

[2]. Blustein, D. L., & Guarino, P. A. (2020). Work and Unemployment in the Time of COVID-19: The Existential Experience of Loss and Fear. The Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 60(5), 702–709.

[3]. Brand, J. E. (2015). The Far-Reaching Impact of Job Loss and Unemployment. Annual Review of Sociology, 41(1), 359–375.

[4]. Petrosky-Nadeau, N., & Valletta, R. G. (2020). An unemployment crisis after the onset of COVID-19. FRBSF Economic Letter, 12, 1-5.

[5]. U.S Bureau of Labour Statistics, URL: https://www.bls.gov/ , last accessed 2023/7/18.

[6]. Gomez-Salvador, R., & Soudan, M. (2022). The US Labor Market after the COVID-19 Recession. SSRN Electronic Journal.

[7]. Ciotti, M. et al. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic. Critical reviews in clinical laboratory sciences, 57(6), 365-388

[8]. Le, K., & Nguyen, M. (2021). The psychological consequences of COVID-19 lockdowns. International Review of Applied Economics, 35(2), 147–163.

[9]. Grabner, S. M., & Tsvetkova, A. (2022). Urban labour market resilience during the Covid-19 pandemic: what is the promise of teleworking? Regional Studies, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print), 1–16.

[10]. Blustein, D. L., et al. (2020). Unemployment in the time of COVID-19: A research agenda. Journal of vocational behavior, 119, 103436.

[11]. Sostero, M., et al. (2020). Teleworkability and the COVID-19 crisis: a new digital divide? . JRC working papers series on labour, education and technology.

[12]. Bartsch, S. M., et al. (2020). The Potential Health Care Costs And Resource Use Associated With COVID-19 In The United States: A simulation estimate of the direct medical costs and health care resource use associated with COVID-19 infections in the United States. Health affairs, 39(6), 927-935.

[13]. Internal Revenue Service, URL: https://www.irs.gov/, last accessed 2023/7/18.

[14]. Hu Xinjian (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 on labor relations and countermeasures Ningbo Economy: Sanjiang Forum (8), 3.

[15]. Huang Qunhui (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 on the supply side and its response: short-term and long-term perspectives Economic Landscape (5), 13.

Cite this article

Li,Q. (2023). Analysis of the Effect of COVID-19 Pandemic to US Unemployment Rate. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,48,172-178.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Financial Technology and Business Analysis

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Holtz, D.,et al. (2020). Interdependence and the cost of uncoordinated responses to COVID-19. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences - PNAS, 117(33), 19837–19843.

[2]. Blustein, D. L., & Guarino, P. A. (2020). Work and Unemployment in the Time of COVID-19: The Existential Experience of Loss and Fear. The Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 60(5), 702–709.

[3]. Brand, J. E. (2015). The Far-Reaching Impact of Job Loss and Unemployment. Annual Review of Sociology, 41(1), 359–375.

[4]. Petrosky-Nadeau, N., & Valletta, R. G. (2020). An unemployment crisis after the onset of COVID-19. FRBSF Economic Letter, 12, 1-5.

[5]. U.S Bureau of Labour Statistics, URL: https://www.bls.gov/ , last accessed 2023/7/18.

[6]. Gomez-Salvador, R., & Soudan, M. (2022). The US Labor Market after the COVID-19 Recession. SSRN Electronic Journal.

[7]. Ciotti, M. et al. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic. Critical reviews in clinical laboratory sciences, 57(6), 365-388

[8]. Le, K., & Nguyen, M. (2021). The psychological consequences of COVID-19 lockdowns. International Review of Applied Economics, 35(2), 147–163.

[9]. Grabner, S. M., & Tsvetkova, A. (2022). Urban labour market resilience during the Covid-19 pandemic: what is the promise of teleworking? Regional Studies, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print), 1–16.

[10]. Blustein, D. L., et al. (2020). Unemployment in the time of COVID-19: A research agenda. Journal of vocational behavior, 119, 103436.

[11]. Sostero, M., et al. (2020). Teleworkability and the COVID-19 crisis: a new digital divide? . JRC working papers series on labour, education and technology.

[12]. Bartsch, S. M., et al. (2020). The Potential Health Care Costs And Resource Use Associated With COVID-19 In The United States: A simulation estimate of the direct medical costs and health care resource use associated with COVID-19 infections in the United States. Health affairs, 39(6), 927-935.

[13]. Internal Revenue Service, URL: https://www.irs.gov/, last accessed 2023/7/18.

[14]. Hu Xinjian (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 on labor relations and countermeasures Ningbo Economy: Sanjiang Forum (8), 3.

[15]. Huang Qunhui (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 on the supply side and its response: short-term and long-term perspectives Economic Landscape (5), 13.