1. Introduction

The continuing declining fertility rate has resulted in a serious issue in several countries, especially some Asian countries including Japan, South Korea, and China. As one of the world’s largest population countries, China has faced a declining birth rate in recent years. Its fertility rate has reached the lowest point in recent decade, which is only 6.77% per 1000 inhabitants in 2022 [1]. Although a smaller population size improves the standard of living for the households, it results in the unbalanced population structure and aging population, thereby suppressing the economic development and growth. To cope with the problems, China government announced the two-child policy in October 2015 to replace the one-child policy, and this family planning policy was fully implemented in 2016, however, it failed to lead to sustained upturn in births rate, therefore, three-child policy was formally passed into law with several resolutions aiming to reduce the burden to raise children in May 2021, to further boost the fertility rate [2].

Chinese adjusted birth policy is essential to restore its population development according to the current situation and issues. However, these family planning measures may not be as effective as the government anticipated due to the changing concepts of young people and high education cost and house prices. These place a burden on the young people today and put pressure on them to raise a child. Using the panel dataset, Xiao and Chi found that when housing prices-to-income ratios exceed a threshold value, they negatively affect the birth rate [3]. Previous studies also found that the marketisation, education level of females, and the percentages of tertiary and secondary industries are structural factors which contributed to the lower fertility rate, especially between 1990 to 2019. The reason for these is rising opportunity cost of employment, so less female choose to give birth children since these will affect their career plan and promotion [4]. As a result, the effectiveness of the policies is heavily related to the female’s rights and the expense of raising children. Many studies have illustrated that both two-child policy and three-child policy will increase women working pressure result in the gender discrimination in the labour market. Hence, safeguarding female’s right and welfare systems are crucial to the success of three-child policy [5, 6].

By summarising the precious studies and explaining their findings, this paper will summarise the previous studies, explaining their results and use these results to continue to explore the pros and cons of the three-child policy in depth. Since the three-child policy is the latest policy, so few studies have been conducted on its effectiveness and impact on female employment and rights. This paper will analyse these points using some empirical evidence to reach a conclusion and suggest recommending methods to improve the policy.

The results found in this paper will give more insights to both the Chinese experts and the policymakers whose countries are facing the low birth rate on the effectiveness of the latest Chinese family planning policy and its influence on the labour market, and the policymakers worldwide can use the results for three-child policy and the suggestions mentioned in the paper as research material to further investigate this field, and then establish better policies which not only can defuse the demographic time bomb globally but also protect female rights.

2. Fertility Rates

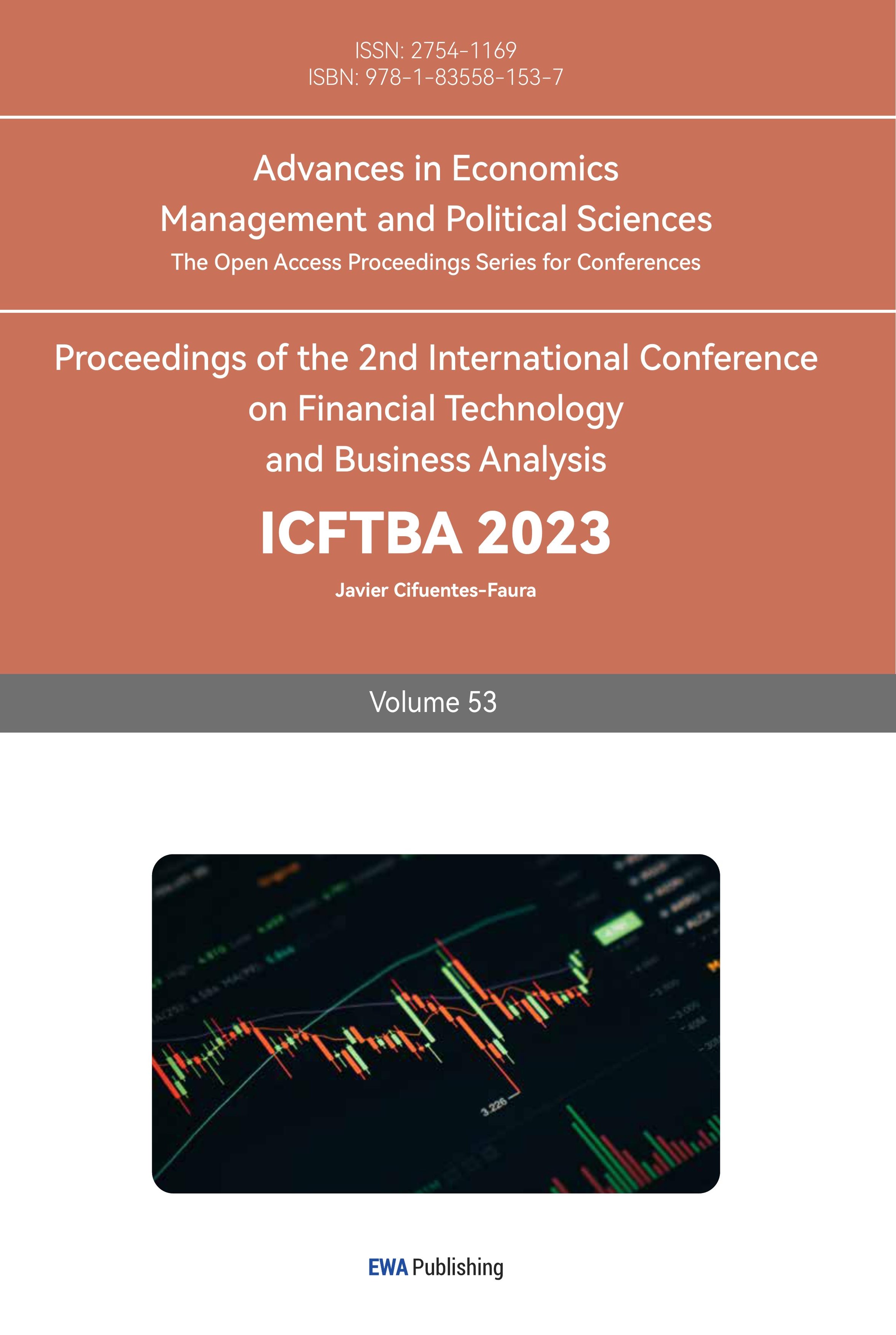

Since the establishment of the three-child policy in 2021, the significant raise in birth rate in China has not been observed. An obvious downward trend can be seen from Figure 1 particular from 2015, and the birth rate even dropped from 7.52% to 6.77% in 2022. And the motive to have a third child has been researched by the cross-sectional study conducted by Jingfei and Yizhou, the results show that among the 1308 respondents with 67.8% female and 32.2% male, 11.5% participants wanted to have more than or equal to three children, but only 9.6% respondents were prepared to have a third child in reality. For the opinion toward the three-child policy, about 27.3% thought the policy was not realistic and 62.2% accepted it [7]. Overall, it was also found that participants generally had inadequate knowledge about the policy, and the most family which have two children have extreme low motive to have a third child.

Figure 1: Chinese fertility rate per 1000 people (%) [1].

The motive to have a third child also linked closely to the education level of the participants, it is found that the individuals with a bachelor’s and master’s degrees have 37.7% and 44.6% lower intention than those with only high-school degree [7]. Generally, these are caused by two reasons. Higher-level educated individuals usually focus more on their own development and career, they tend to spend more time and energy on their earning. Since women are already in a stressed position in the workplace, maternity leave seriously affects their possibility of promotion and wage level, some female employees may even lose their job after they give birth to the child. Many female employees even have to become full-time housewives to take after their children due to the unbalanced family structure in China; they normally get much lower pay when they return to work due to workplace gender discrimination. The higher educated people tend not to have more children since they have higher pensions after retirement, so they can live on their pensions, instead of getting economic support from their adult children. In contrast, because of the high childcare costs such as tuition fees caused by the fierce competition in school and the numerous time spent on children, they are tired of balancing between children and work, so they prefer to spend those money on themselves.

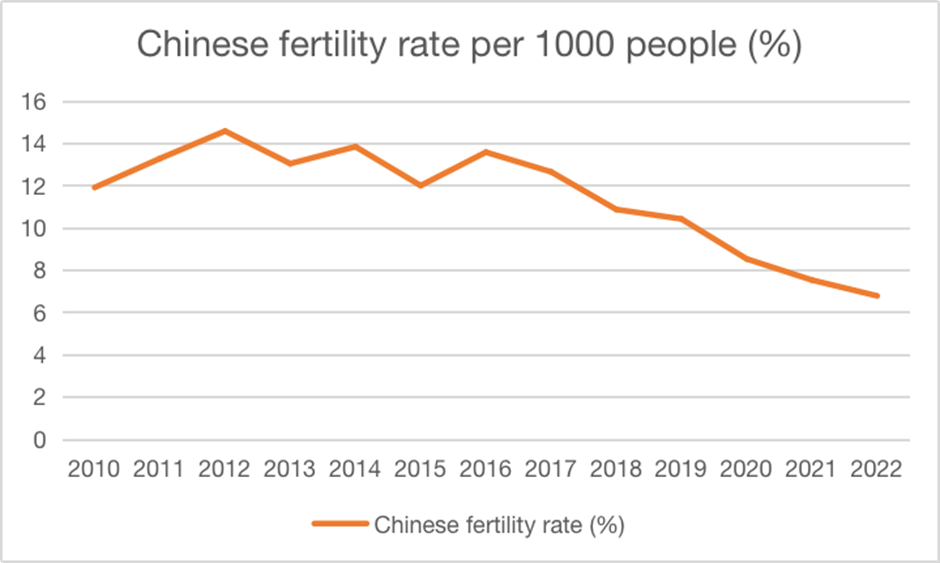

To cope with these problems, Chinese government sets lots of subsidies to those family who give birth to the third child. For instance, the maternity allowance and one-time nutrition allowance are provided with 10000 yuan per year, and one-time subsidies are given to the families, which is 25% of the person’s annual average monthly wage. Medical expense including parental medical expenses, maternity medical expenses, and family planning medical expenses are offered to those parents, providing them economics supports and reducing the childcare fees [8]. However, a larger survey with 31000 participants conducted by the state news agency Xinhua in June 2021 still revealed that only 4.5% were considered to have a third child, and 90% said no [9]. And since the literacy is rising and more female graduates, fewer and fewer people choose to have children just as what is shown in Figure 2 [10,11]. Consequently, the three-child policy seems ineffective in changing the minds of these young people to have more children, and the policy has not increased the birth rate until now.

Figure 2: Relationship between the Chinese fertility rate, proportion of female graduate students and female literacy rate [12-14].

3. Female Labour Employment

Since the enforcement of the two-child policy, although no decrease was observed in the female employment, the policy weakened the positive effect to hire female, so these worsen gender discrimination in the labour market [6]. This causes economic loss for both female employees and the firms since the employer discrimination theory revealed the raising percentages of women employees in a firm increases the firm’s profits, therefore, the policy could harm the economic benefits and development of the Chinese society [10].

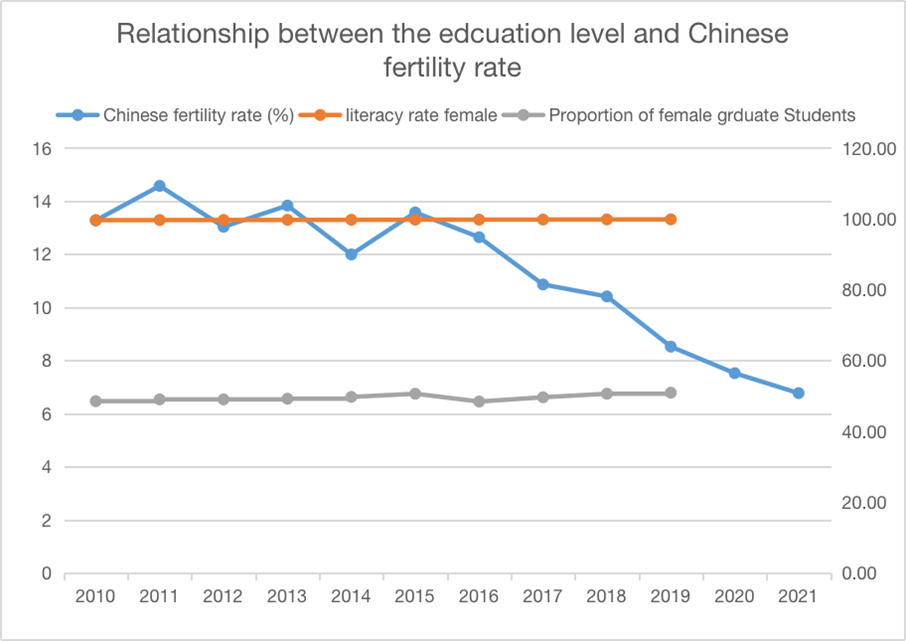

Government established lots of policies to increase female employees’ welfare, etc. The 128 days of maternity leave are given to the women who give birth to the third child. The prenatal leave and lactation leave were also passed into law, and the firm should pay employees 80% of their salaries during this time. These policies protect the female employees’ wage during the maternity leave and allow them to rest and recover from the pregnancy. However, these policies do not protect the female employees’ right since in this case, the three-child policy causes lots of firms directly not to hire the female at the start or after the maternity, and these aggravate the gender discrimination in the workplace, and may lead to the lower employment and wage for those female employees. The interview conducted by Hanyu Cai, Xingyao Wang and Zhile Wang on 9 women differing by age, job, and education level shows that only 2 of them did not experience discrimination in the workplace; they said pregnant women will bring extra cost to the companies and some even expressed that their job has been replaced by others after the pregnant holidays. Their attitude towards the three-child policy is most negative, they believe more measures are needed to ensure that it is effective [5]. In turn, the three-child policy institutionalises the gender discrimination in Chinese labour market, as more employers refuse to hire women who considering having a third child due to high maternity leave costs [11]. It also can be observed from the Figures 3-4, both female labour participate rate, and the gender pay gap has reduced since 2021[15,16]. The China labour force participation rate has seen a generally downward tendency since 1990, it then has reached the bottom in 2020 in the recent 20 years due to COVID-19 pandemic, and the rate recovered back to 61.31% in 2021, however, it still dropped to 61.07% in 2022. The gender wage gap was 2222 yuan in 2019, but it is only 1231 in 2022, which is only half of the former. To some extent, these phenomena are caused by gender discrimination that resulted from the three-child policy. The National Bureau of Statistics’ report marked that the percentages of women choose to continue their education after post-graduation in 2019 was 50.6% of the total, and there are 51.7% and 58.7% women are in undergraduate college and adult higher education, therefore women are more inclined than men to continue higher studies [12].The gender discrimination in the labour market really is a waste of human capital resources, which causes inefficient in the labour market, and these would lower both the profits and economic benefits of the firms and society.

Figure 3: China female labour force participation rate over 15 (%) [15].

Figure 4: China gender wage gap [16].

4. Conclusion

The three-child policy can indeed increase workplace pressure for women and negatively affect female employment and wages; it exacerbates the gender discrimination in the Chinese labour market. Although several subsidies and policies are dressed to provide economic support to women and families who give birth to a third child to improve the welfare of those females, aiming at boosting the fertility rate, it seems the policy is ineffective with regards to the available resources and data, and most young people maintain their own adverse attitude to these policies and refuse to have more children due to their concepts and expensive costs of raising a child. Nonetheless, the research in this paper still has many limitations and needs to be improved. While data and figures can illustrate the consequences of the three-child policy to some extent, more quantitative analyses, such as modelling, are still indispensable in future research to reach a more accurate and comprehensive conclusion if more data are available. Furthermore, since the application of the policy in 2021, only two and a half years have been passed, accordingly, there can be a time-lag effect for this policy, and it may appear to increase the birth rate after.

As a result, the three-child policy seems almost ineffective at increasing the birth rate at this point and the aging population will remain serious concern. However, the policy may become successful shortly thereafter due to the limitations, hence, more research is required to reach a conclusion. As a matter of fact, there should be more incentives or special allowances to alleviate the gender discrimination in the workplace and improve equality, more insurance of the job should be given to the female who give birth to the child, and more incentives should be provided to those companies which hired female workers to encourage companies to hire female employees, thus protecting female’s employment and rights, and then women may be willing to give birth to more children.

References

[1]. National Bureau of Statistics (2013). Annual data. Retrieved from https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=C01

[2]. BBC (2021). China NPC: Three-child policy formally passed into law. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-china-58277473

[3]. Cuiyin, X., Weisu, C. (2021) Price and China’s Birth Rate: A Note. Asian Economics Letter,1-2.

[4]. Lidan, Y., Jiahong, G. and Shixiong, C. (2022) What structural factors have held back China’s birth rate. Environment, Develpoment and Sustainability, 1-12.

[5]. Hanyu, C., Xingyao, w. and Zhile, W. (2022) The Effects of Three-Child Policy on Women in Workplaces. Atlantis Press, 297-298.

[6]. Aolin, L., Fuli, K. (2022) Impact of two-child policy on female employment and corporate performance: Empirical evidence from Chinese listed companies from 2010 to 2020. Humanities & Social Sciences Communications, 1-11.

[7]. Ni, N., Jingfei, T. and Yizhou, H. et.al (2022) fertility Intention to have a Third Child in China following the Three -Child Policy: A Cross-Sectional Study. MDPI, 3-10.

[8]. Guangming Daily (2022). Extending maternity leave, promoting universal childcare services, and granting birth allowances - supporting measures for the three-child policy are being introduced one after another. Retrieved from https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-01/21/content_5669636.htm

[9]. Megan, T. (2021) China’s three-child policy. World Report, 1-2.

[10]. Kawaguchi D (2007) A market test for sex discrimination: evidence from Japanese firm-level panel data. Int J Ind Org 25, 3, 441–460.

[11]. INDEPENDENT (2021). What effect will China’s three-child policy have on working women. Retrieved from https://www.independent.co.uk/asia/china/china-three-children-women-b1859685.html

[12]. China Daily (2020). More women in higher education is good news. Retrieved from http://global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202012/24/WS5fe3dcb7a31024ad0ba9de9a.html

[13]. GlobalData(2022). Female Literacy Rate in China. Retrieved from https://www.globaldata.comRising Wage Inequality and Postgraduate Education/data-insights/macroeconomic/female-literacy-rate-in-china/

[14]. National Bureau of Statistics (2021). Final Statistical Monitoring Report on the Implementation of China National Program for Women’s Development. Retrieved from http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/202112/t20211231_1825801.html

[15]. The World Bank (2023) Labour force participation rate, female, China. Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.CACT.FE.ZS?locations=CN

[16]. Statista (2022). Average monthly income among male and female respondents in China from 2019 to 2022. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1116666/china-average-monthly-income-by-gender/#:~:text=According%20to%20a%20survey%20about,female%20respondents%20was%208%2C138%20yuan.

Cite this article

Xu,K. (2023). Research on the Impact of Implementing the Three Child Policy: Perspective from a Social and Economic. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,53,46-51.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Financial Technology and Business Analysis

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. National Bureau of Statistics (2013). Annual data. Retrieved from https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=C01

[2]. BBC (2021). China NPC: Three-child policy formally passed into law. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-china-58277473

[3]. Cuiyin, X., Weisu, C. (2021) Price and China’s Birth Rate: A Note. Asian Economics Letter,1-2.

[4]. Lidan, Y., Jiahong, G. and Shixiong, C. (2022) What structural factors have held back China’s birth rate. Environment, Develpoment and Sustainability, 1-12.

[5]. Hanyu, C., Xingyao, w. and Zhile, W. (2022) The Effects of Three-Child Policy on Women in Workplaces. Atlantis Press, 297-298.

[6]. Aolin, L., Fuli, K. (2022) Impact of two-child policy on female employment and corporate performance: Empirical evidence from Chinese listed companies from 2010 to 2020. Humanities & Social Sciences Communications, 1-11.

[7]. Ni, N., Jingfei, T. and Yizhou, H. et.al (2022) fertility Intention to have a Third Child in China following the Three -Child Policy: A Cross-Sectional Study. MDPI, 3-10.

[8]. Guangming Daily (2022). Extending maternity leave, promoting universal childcare services, and granting birth allowances - supporting measures for the three-child policy are being introduced one after another. Retrieved from https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-01/21/content_5669636.htm

[9]. Megan, T. (2021) China’s three-child policy. World Report, 1-2.

[10]. Kawaguchi D (2007) A market test for sex discrimination: evidence from Japanese firm-level panel data. Int J Ind Org 25, 3, 441–460.

[11]. INDEPENDENT (2021). What effect will China’s three-child policy have on working women. Retrieved from https://www.independent.co.uk/asia/china/china-three-children-women-b1859685.html

[12]. China Daily (2020). More women in higher education is good news. Retrieved from http://global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202012/24/WS5fe3dcb7a31024ad0ba9de9a.html

[13]. GlobalData(2022). Female Literacy Rate in China. Retrieved from https://www.globaldata.comRising Wage Inequality and Postgraduate Education/data-insights/macroeconomic/female-literacy-rate-in-china/

[14]. National Bureau of Statistics (2021). Final Statistical Monitoring Report on the Implementation of China National Program for Women’s Development. Retrieved from http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/202112/t20211231_1825801.html

[15]. The World Bank (2023) Labour force participation rate, female, China. Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.CACT.FE.ZS?locations=CN

[16]. Statista (2022). Average monthly income among male and female respondents in China from 2019 to 2022. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1116666/china-average-monthly-income-by-gender/#:~:text=According%20to%20a%20survey%20about,female%20respondents%20was%208%2C138%20yuan.