1. Introduction

At a time when the female labor force accounts for about 50 percent of the working population, female workers account for only 37-39 percent of workers. Female employment is much lower than that of males [1]. So in the 1970s, China implemented a series of policies and reforms aimed at promoting equality, development and sharing for women. These efforts have yielded positive results and have safeguarded the equal rights of men and women to employment. The survey results also show that women’s education level is generally lower than men’s education level [2]. However, with the development of society, women’s educational level has gradually increased, and many women’s opportunities to receive higher education are comparable to those of men. With the increase in educational opportunities as well as the level of education, women’s cognitive level is also gradually increasing, and the traditional concept that women should stay at home and raise their children is no longer adapted to modern women, who have begun to go out to work and seek economic independence [3]. Because there is a significant decline in the labor force participation rate and employment rate of workers whose education level is equal to or lower than the secondary school level [4], the increase in women’s education has led to the competitiveness of women in the job market. With economic development and progress, the supply and demand in the labor market has also changed, and women are no longer confined to traditionally female occupations, but have begun to enter occupations that were initially considered to be in the “public domain”. This has led to the diversification of many companies and jobs, and this diversification has given women a wider range of choices in the job market. The popularization of the concept of gender equality has provided more employment opportunities for women, and the gap between the employment rates of women and men has gradually narrowed.

The problem in the current society is that despite the narrowing of the employment rate gap, women are still at a disadvantage at the top management and decision-making levels. Women still face difficulties and prejudices in certain sectors and positions, despite the apparent promotion of gender equality. As well as the fact that there is still a wage gap between men and women, with women’s average wages usually lower than men’s. “Women are more clustered in industries with relatively low average wage and skill composition, such as agriculture, retail trade and science, education, culture and health, while men are more clustered in industries with relatively high average wage and skill composition, such as construction, transportation and telecommunication, and public administration.”[5]. And another important reason for developing countries is that in China, when women have children they still find a balance between family and career, and some of them even return to their families for the sake of their children.

In this paper, in the context of today’s research, it is understood that a significant portion of women’s employment rates will be influenced by the economy, family, urban, and policy. In the development stage of rapid urbanization in China, the concentration of the employed population and the transformation and upgrading of the industrial structure have led to a structural imbalance in the employment of women in China, despite the fact that the level of education has been raised year by year. In order to adapt to the development characteristics of rapid urbanization and alleviate the pressure on female employment, targeted countermeasures have been proposed for the balanced development of female sex education and employment so as to enhance the employment competitiveness of women in society. It is essential for women to enhance their competitiveness in employment in society [6]. In terms of employment scale, the employment gap between the sexes has further widened, and the employment rate of urban women has been more affected [7]. As women’s educational attainment and labor force participation rates increase, female employment rates and female voices are receiving increasing attention. The shortcomings and gaps in previous research lie in the lack of detailed analysis and quantitative assessment of the gender employment gap. Existing research has focused too much on the causes and measures of the rise in female employment and less on the causes and effects of the fall in male employment. Since most of the studies focus on developed countries, there is still insufficient research on developing countries and countries with different cultural backgrounds. Therefore, this paper puts more emphasis on the proportion of the gender gap in the study of female employment rate, and the main research context is China in developing countries where there is a lack of research.

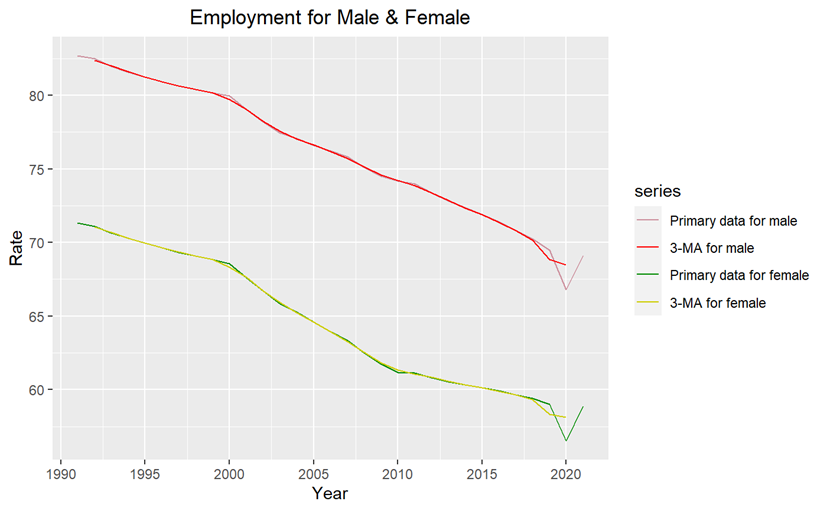

This study finds that China’s working age population and labor force participation rate have been declining in recent decades. According to the raw data, since 1991, China’s female employment rate has declined from 71.34% in 1991 to 58.88% in 2021, and the male employment rate has also declined from 82.67% to 69.12% in 30 years. This decline has received a lot of attention, for example, in order to increase the working-age population, China’s central government has been implementing a “two-child” policy since 2013, and has even proposed a “three-child” policy by the end of May 2021, in order to increase the working-age population. At the same time, while the focus on equality for all has been emphasized, further and more complex challenges remain as a result of some of the subsequent gender discrimination in work and life. This paper follows up with a comprehensive analysis of the causes of the decline in employment between men and women in terms of policy, economic, social and technological aspects using PEST analysis. The original study is supplemented by a special focus on the year 2023, both economically and in terms of modern technological advances after the outbreak of COVID-19.

The rest of this paper is divided into modeling methodology, data source, and R prediction. The data for this paper comes from the World Bank data on the employment rate of men and women over the age of 15 in China, and the study will analyze the data collected by the World Bank descriptively, including the mean, variance, and so on. The data collected by the World Bank will be analyzed using R for evaluation. R will then be used to analyze the underlying trends in our time series using the ETS model and the ARIMA forecasting model, which will predict and estimate the proportional gap between the male and female rates in China’s employment levels. The conclusion learns that both male and female employment rates are declining and the gap between the two is narrowing. The ETS predicts a steady downward trend over the next 10 years. From ARIMA, we obtained autocorrelation results between each data point and its lagged version in the time series data. Subsequently, a pest analysis was conducted to explain the changes in the data of the two models in order to predict the future trend of the time series. The final conclusion is that the reasons for the decline in the employment rate of men and women in China are multifaceted and are the result of a combination of policy, economic, social, scientific and technological aspects. It is necessary to promote economic restructuring, solve the problem of population aging, encourage female employment, and increase the employment rate of both men and women. In the conclusion section, more detailed reasons will be discussed and the limitations of this paper will be mentioned for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Status Analysis

The problem of low female employment rate and gender discrimination in employment has been a concern in China. In order to improve this problem, previous researchers have focused on policy, education level and family. The decline in employment rates for both men and women also needs to be analyzed in terms of the aging population, the economy, and technology.

The paper used the national policy to show that China will reduce the employment rate of men and women. For the issue of women and the economy, the Platform puts forward the following main goals: to guarantee women’s equal enjoyment of labor rights and to eliminate gender discrimination in employment [8]. For China, a developing country, after the reform and opening up of China, the relative changes in the employment situation of Chinese women, othre researchers used the data from the 1982, 1990, 2000 census and the 2005 China 1% Population Sampling Survey to illustrate the changes in the structure of women’s employment, and concluded from this literature that during the transition period, the employment rate of women declined while the employment field expanded and the occupational structure optimized. fields expand and the occupational structure is optimized, and this change creates social mobility in different directions for female groups, with some urban and rural females achieving upward occupational mobility while others are marginalized due to difficulties in finding employment and so on [5].

2.2. Educational Factor

The study analyzes the employment effect of urban women’s education level and concludes that since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the education level of urban women in China has been continuously improved, and due to the improvement of the education level, the employment rate of women has been relatively improved [6]. However, others analyzed the success rate of women’s job application in Xi’an with research hypothesis and methodology, and concluded that more and more women are engaged in high-wage modern occupations, but at the same time, the phenomenon of gender discrimination in employment still exists, and in recent years there has been a clear retrogressive trend of aggravation of gender discrimination [2]. In this situation, we need to study the impact of female employment rate for socio-economic development.

Exits papers used the national data from 1996 to 2006 to conduct linear regression analysis to establish a regression model, and concluded that female employment and economic development are negatively correlated, which is in conflict with the commonly held view that economic development provides more jobs and promotes female employment [1]. Many enconomists also used CHIP data selection and descriptive statistics in the same way as Hao Ran, he also used a fixed effects model for regression analysis, the results show that the urban variables as well as the individual variables can better explain the level of employment, indicating that trade openness, the introduction of foreign investment and individual characteristics will have a greater impact on employment. However, the individual variables, as well as the effect of marriage on employment is negatively correlated [3].

2.3. Economic Factor

For the aforementioned idea that economic development affects women’s employment rate, all-media reporter reports something more tangible: the number of women employed in this economy during the recovery from the COVID-19 epidemic is expected to be 13 million fewer than in 2019, whereas the number of men employed was able to recover to the 2019 level, which further exacerbates the workplace Gender inequality [9]. In response, the Qing Research Institute also offers country-by-country responses to secure women’s employment: the UK government has temporarily reduced VAT rates for crisis-affected businesses. Businesses in the retail, hospitality and leisure sectors, where women are over-represented, are entitled to a one-off cash grant of up to £25,000 from their local council [10]. But another literature gives a different result, for the same economic downturn during the Great Depression, the number of women employed in the United States rose instead of declining in the face of unusually high national unemployment. They use the demand for labor to conclude that the growth in female employment was a result of the expansion of the female labor market during the Great Depression, a product of past and current gender discrimination, and that this increase in employment therefore did not imply a relative improvement in women’s economic and social status [11].

2.4. Family Factor

It is not only the economy that leads to the decrease of female employment rate, but also the maximization of family income is a very big reason. The article analyzed the factors affecting women’s employment and learned that due to China’s overall economic level not being high, the family income mainly comes from the income of both men and women. This requires women to be engaged in family business and social business at the same time, to obtain income, to maximize family income [12], which also makes women lose employment opportunities. But some also studied the impact of fertility on women’s employment, she also used the CHIP data to analyze the results of the basic regression on women and families, which showed that with the increase in the number of children, women prefer to spend time at home and withdraw from the labor market when balancing family and work [7].

2.5. Male and Female Employment Falls

But the fact is that it is not only women’s employment rate that is declining, but men’s employment rate is declining as well. Researchers used descriptive statistics to show that the labor force participation rate and employment rate in China have been declining since 2010; among the local working-age population in urban areas, there is a significant decline in the labor force participation rate and employment rate of workers with education equal to or lower than the secondary school level [4]. In this regard, the paper focused on efficient graduates with multiple linear regression between the teacher-student ratio and the employment rate. There is a significant positive correlation, while the proportion of the tertiary industry, which characterizes the industrial structure, has a significant negative impact on the employment rate. Therefore, the most important and fundamental thing is to change as soon as possible from focusing on “employment rate” to focusing on “employment competitiveness” [13].

A very important reason for the decline in employment rate is also due to population aging, others based on the panel data of the World Bank in 50 countries and regions from 1990 to 2017, empirically examined the relationship between population aging, economic growth and women’s employment, and the empirical results show that: the aging of the population can significantly increase women’s employment rate, and economic growth and women’s employment rate shows a U-shaped relationship. The empirical results show that population aging can significantly increase female employment rate, while economic growth and female employment rate show a U-shaped relationship [14].

At the same time, in the rapid progress of science and technology some study used a combination of China’s inter-provincial data from 2000-2018, using dynamic panel regression and moderated effects model test found that: technological progress has a promotional effect on the employment rate of both men and women in China, but because of its stronger promotion of male employment, resulting in the strengthening of the gender employment gap [15].

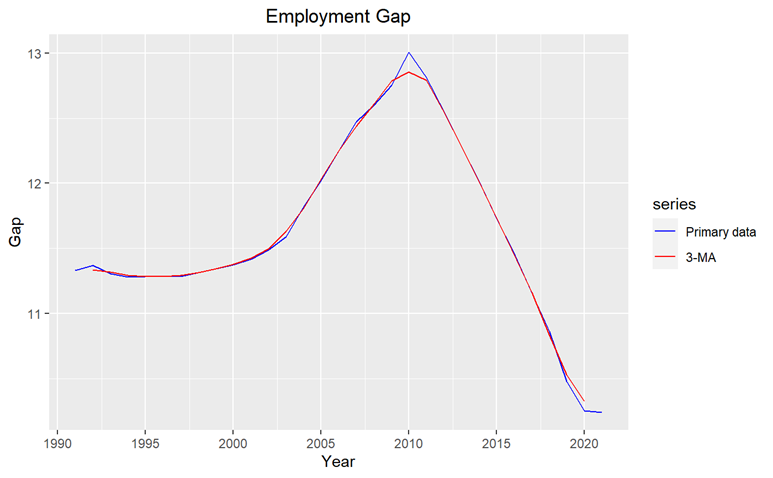

3. Employment Rate Gap

By combining the two charts, we find that female’s employment has fallen significantly more than males since 2000. To explore this change further, we construct a new variable: the difference between male and female employment rates. We want to explore the employment gap between male and females through the analysis of this difference. If the difference between the employment rates of male and females increases, it indicates that the employment gap between them is increasing. Using the method of moving average, we find that the gap between male and female employment rates has been rising every year since around 2000 and peaked in 2010. Since then, the gap between male and female employment rates has narrowed every year.

Figure 1: Employment for Male and Female.

Figure 2: Employment Gap.

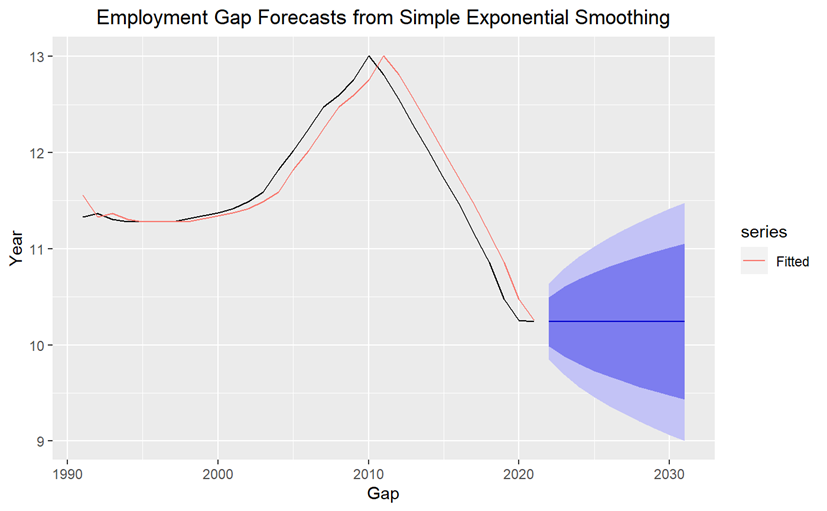

3.1. Employment rate Gap Forecast from Simple Exponential Smoothing

This study initially used Simple Exponential Smoothing to predict the gender employment gap, and as you can see from the figure below, the forecast is uncertain about the employment gap over the ten-year forecast period.

Figure 3: Employment Gap Forecast from Simple Exponential Smoothing.

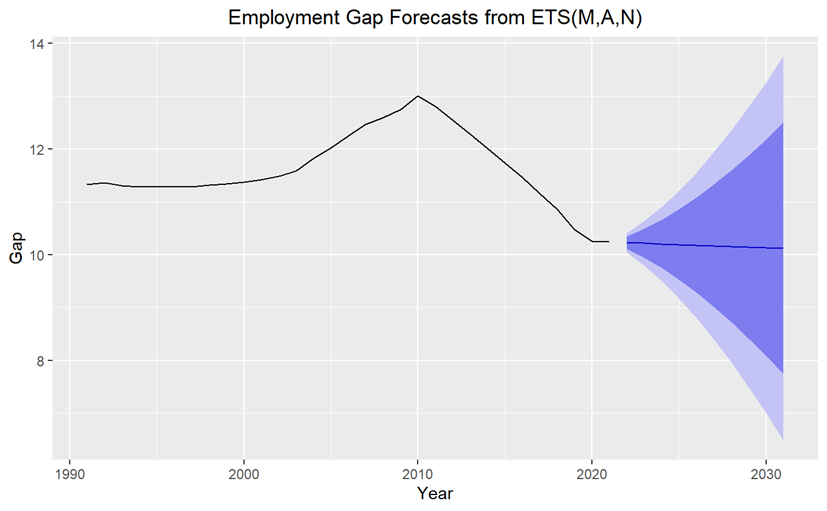

3.2. Employment Gap Forecasts from ETS Model

This paper used the ETS statistical framework to make predictions. This paper lets the ets() function select the model by minimizing AICC. The model chosen is the Holt linear method with multiplicative error, which is ETS (M,A,N). Using the ETS statistical framework, this paper ends up with a 10-year projection of the gender employment gap, which is in the 8% to 13% range. And it may show a steady and slight downward trend.

Figure 4: Employment Gap Forecasts from ETS.

3.3. Employment Gap Forecasts from ARIMA Model

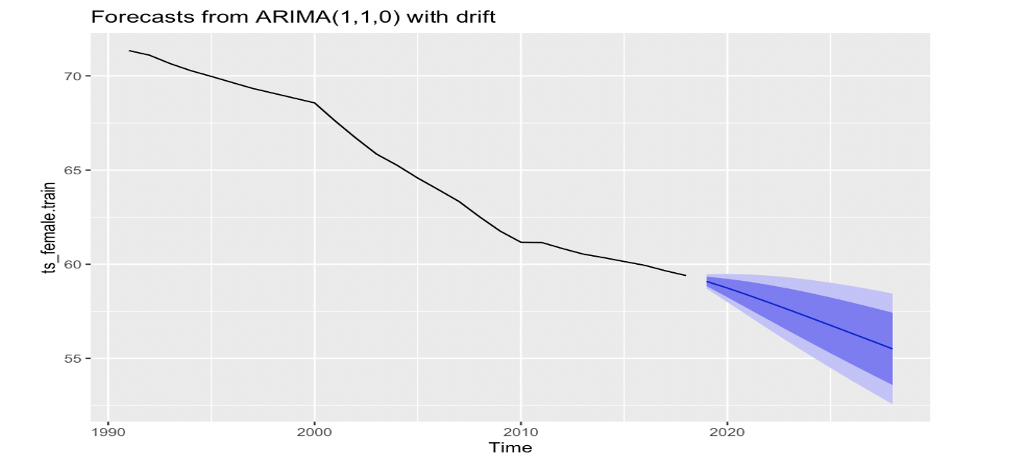

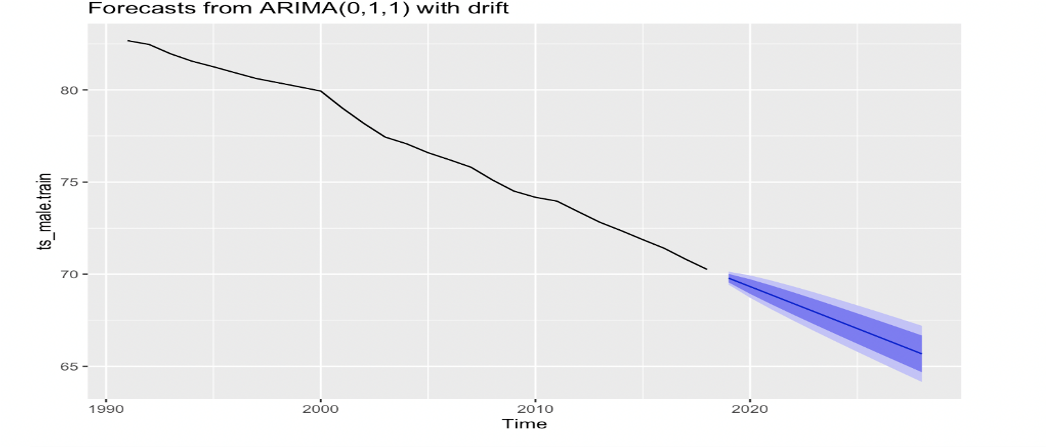

When this paper analyzes the ARIMA analysis model, this paper can find that from 1990 to 2020, there is an overall downward trend in the data for men and women in the ARIMA prediction coordinates. And it can be seen that the data of men is generally larger than that of women.

Figure 5: Forecasts from ARIMA.

In terms of the number of forecast periods for men and women, the data of women was close to 111 and that of men was more than 130. Moreover, the predicted data showed that the expected instability was greater for men than for women. This paper speculates that the reason why the employment rate began to show a downward trend in 1990 may be the marketization of the national economy and the bankruptcy and reorganization reform of many enterprises, which is an inevitable reflection of the transition from the planned economy to the market economy and an inevitable trend of economic development.

Figure 6: Forecasts from ARIMA.

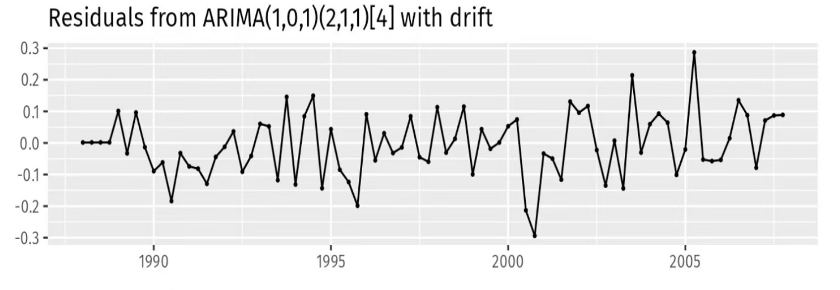

When this paper looks at the time series plot, this study can see that the overall data has a long-term downward trend, and the fluctuations are cyclical, with a negative low between 2000 and 2005 and a positive high after 2005.

Figure 7: Residuals from ARIMA with drift.

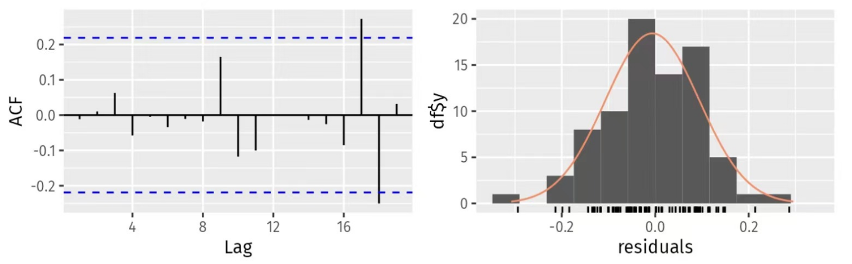

Autocorrelation relates to the correlation of observations over time, and this study can learn a lot from ACF graphs. From the autocorrelation this research can see that this is a “truncation”. The whole model satisfies ARIMA (1,0,1) (2,1,1) [5]. From other data, there is great uncertainty about the future ratio of male to female employment, which still needs to be analyzed and considered.

Figure 8: Lag and Residuals.

3.4. PEST Background Analysis

For the reason that there are some parts of the figure that have turning points or the overall downward trend, this paper would like to explain it from the PEST background analysis in addition to the data or models mentioned above. It analyzes and predicts the four main external factors that may affect the employment rate of men and women over 15 years old in China: political, economic, social and technological environments. This analysis helps to understand the overall trend of the employment rate in order to further estimate the forecast. The following is a specific analysis of the PEST context for the employment rate of men and women over fifteen in China.

3.4.1. Political Factors

Inequalities in the political system may make it difficult for women to have access to equitable employment opportunities, thus affecting the balance between male and female employment rates. To address the issue of women and the economy, the Platform puts forward the following main objectives: to guarantee women’s equal enjoyment of labor rights and eliminate gender discrimination in employment; to maintain the proportion of women in the workforce at more than 40%, with a gradual increase in the number of women working in urban and rural units; and to narrow the gap between men’s and women’s non-agricultural employment rates and men’s and women’s incomes [8]. The progress of the policy has substantially helped to narrow the gap between the employment rates of men and women.

3.4.2. Economic Factors

For economic factors, female employment has a great impact on social and economic development, such as low female employment rate, which hinders the growth of the national economy; low female employment rate, which leads to the lack of effective social demand, which hinders the social and economic development; and the existence of female poverty, which results in the continuation of cultural poverty, which affects the quality of the whole population [12]. However, if China is in an economic down cycle, companies may reduce hiring, resulting in fewer employment opportunities, which affects both male and female employment rates. This paper can clearly see in the chart above that there is an important turning point in 2020 for both male and female employment rates. In my opinion, this turning point may be due to the fact that when the COVID -19 broke out, China’s economy was in a rapid decline and there was a lot of internal and external pressures, with many businesses facing closure. The International Labor Organization (ILO) recently stated that the disproportionate employment and income losses suffered by women during the COVID-19 outbreak, as well as gender inequality in the workplace, which was further exacerbated during the outbreak, will continue in the near future [9]. Even in some developed countries female employment has been significantly impacted for reasons that include, but are not limited to, industry. The outbreak of the COVID-19 mainly led to layoffs in service industries such as restaurants, food production, hospitality, and retail, which themselves are dominated by female employment [10]. As a result, employment in China begins to trend upward a bit in 2020 as a result of the recovery from the epidemic.

3.4.3. Social Factors

Social Factors are due to the fact that there is a mismatch between the demand in many labor markets now and the education or skills of the people looking for work. Better education does not match better jobs, and then many people will have a hard time finding the right job. In an era when college students are common, jobs are limited, which leads to the fact that many college students may need to go to jobs that don’t require college or brain power, which may also lead to a decline in employment. In fact, affected by factors such as the scale of graduates, the quality of education, the level of the economy and industrial restructuring, the initial employment rate of graduates has fluctuated frequently since 2003, and the overall level is not high [13]. Regardless of men and women, the overall employment rate of Chinese college graduates has declined.

Another very important social factor is the aging of the population. It is understood that our country has also stepped into the aging society, according to the latest news from the World Bank, the aging rate of our population has reached 11%, ranking the tenth highest in the world’s aging countries, and the female labor force participation rate has also decreased by 10% from 1990 to 2018 [14]. So this paper needs to use the fertility policy to promote industrial structure transformation and upgrading to further solve the problem of population aging.

3.4.4. Technology Factors

Due to the advancement of modern technology, a lot of smart artificial intelligence and machines have entered people’s lives. This may lead to some traditional jobs being replaced by automation or machines, thus affecting the employment opportunities of men and women in different industries. Advanced production tools and production methods will replace part of the original labor force, thus increasing short-term unemployment. Technological progress and skilled labor have become more closely intertwined, which means that technological progress is inevitably accompanied by a higher demand for skilled labor, leading to a “natural” imbalance in its “destructive effect” on employment at the gender level: on the one hand, the reality is that highly skilled labor is mostly male, while women are more likely to be in the labor force in different industries than men. On the one hand, the reality of the highly skilled labor force is mostly men, and women are at a relative disadvantage in terms of skills [15]. Therefore, the progress of science and technology will not only lead to a decline in the employment rate of men and women, but also widen the gap between men and women’s employment rates.

3.4.5. Analysis

To summarize, both the PEST background analysis and the data analysis conclude that the employment rate of men and women over the age of 15 in China will decline. As well as the economic, social and technological factors, it is also found that the gap between male and female employment rates in China will widen. Although the modeling and data predictions are still in a continuous decline, This research needs to put all the factors together to find a good solution.

4. Conclusion

The data analyzed above, as well as the projected ETS and ARIMA graphs, show that both men’s and women’s fifteen-plus employment ratios are declining in China, and the distance between the two ratios is decreasing. However, they both have a clear turning point in 2020, the likelihood of which this paper will discuss below. When this study went to observe the model with data firstly it was necessary to have found enough time series data in order to find the appropriate model parameters. Then, the fitting and prediction of the ETS and ARIMA models can be performed using R. The graphs of the ETS show that the employment ratios of both men and women over the age of fifteen in China are all trending downward, which may be slightly different, but are generally similar. The 10-year trend predicted by the ETS is a steady downward trend. From ARIMA this study gets the result of autocorrelation, the correlation between each data point in the time series data and its lagged version. As well as this data shows a truncated tail, which means that the correlation coefficient suddenly becomes zero.

For the above analysis, this paper hopes to further increase the enforcement of the Law on the Protection of Women’s Rights and Interests and other laws and regulations, as well as updating more specific systems according to the reality of the aging and the rapid development of science and technology in the society. Continuously improve the employment environment for women workers to promote women’s development. In response to the decline in employment rates for both men and women in China, it is hoped that the Labor Law will be reformed to implement political guarantees that are assisted by science and technology, rather than replaced by them.

References

[1]. Haoran. Analysis of Influencing Factors on Women’s Employment in China [J]. Shandong Social Sciences, 2009, 01 issue: 116-119.

[2]. Wu Yanfang. An Analytical Study on the Success Rate of Female Job Applicants: A Case Study of Xi’an[J]. Modern Communication, 2011(04). Xi’an Academy of Foreign Affairs.

[3]. Lin Lin. Empirical Analysis of the Impact of Economic Openness on Female Employment in China[J]. Journal of Shandong University of Finance and Economics, 2016, 08. Online Publication Date: 2016-07-16 to 2016-08-15.

[4]. Wu Yaowu. Changes in China’s labor participation rate: Continuing decline or rebound?[J]. Labor Economics Research, 2021, 04: 118-141.

[5]. Li Xiaoxing. Changes in the Scale and Structure of Female Employment in China since the Reform and Opening Up[J]. Journal of Nanjing College of Population Programme Management, 2010, 03: 17-22.

[6]. Yang Yinglan. The impact of education level on employment of urban women. Journal of Dalian University of Technology, 2016, No. 03, Page(s).

[7]. Sun Bei. Analysis of the Impact of Economic Openness and Fertility Rate on Female Employment in China: Based on 1993-2011 CHNS Data[J]. Journal of Shandong University of Finance and Economics, 2019, 08. Online Publication Date: 2019-07-16 to 2019-08-15.

[8]. Xinhua. China to reduce the gap in employment rates and income between men and women[J]. World of Labor Security, 2011, 09: 10.

[9]. He Meng. International Labour Organization: Women’s Re-employment Numbers Post-pandemic Will Be Lower Than Men’s[N]. Global Women’s Perspective, 2021-07-28.

[10]. Qing Research Institute. Under the Pandemic: Significant Impact on Female Employment[R]. Qing Research Institute Series Report, 2021, No.3, June 2021.

[11]. Yang Lihong^1, Zhou Wenji^2. Rising or Declining? - An Analysis of the Reasons for the Increase in the Number of Employed Women in the US during the Great Depression[J]. Times of Vicissitudes, 2008, 05.

[12]. Kuang Aiping. The Impact of Female Employment on China’s Economic Development[J]. Modernization of the Marketplace, 2005, 26: 193-194.

[13]. Wang Sufeng. Evolution and influencing factors of the employment rate of graduates from regular universities in China from 2003 to 2010[J]. Journal of Wanxi University, 2014, 01: 54-57.

[14]. Zhou Yuzhong. Population aging, economic growth, and women’s employment: Empirical evidence based on cross-national panel data. Journal of Jingchu Institute of Technology, 2020, 03: 70-77.

[15]. Zhu Yi. Has technological progress exacerbated the gender employment gap?[J]. Modern Finance & Economics (Journal of Tianjin University of Finance and Economics), 2020, 10: 97-114.

Cite this article

Zhang,Y. (2023). Comparison of Male and Female Labor Force and Employment Levels in China. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,53,297-306.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Financial Technology and Business Analysis

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Haoran. Analysis of Influencing Factors on Women’s Employment in China [J]. Shandong Social Sciences, 2009, 01 issue: 116-119.

[2]. Wu Yanfang. An Analytical Study on the Success Rate of Female Job Applicants: A Case Study of Xi’an[J]. Modern Communication, 2011(04). Xi’an Academy of Foreign Affairs.

[3]. Lin Lin. Empirical Analysis of the Impact of Economic Openness on Female Employment in China[J]. Journal of Shandong University of Finance and Economics, 2016, 08. Online Publication Date: 2016-07-16 to 2016-08-15.

[4]. Wu Yaowu. Changes in China’s labor participation rate: Continuing decline or rebound?[J]. Labor Economics Research, 2021, 04: 118-141.

[5]. Li Xiaoxing. Changes in the Scale and Structure of Female Employment in China since the Reform and Opening Up[J]. Journal of Nanjing College of Population Programme Management, 2010, 03: 17-22.

[6]. Yang Yinglan. The impact of education level on employment of urban women. Journal of Dalian University of Technology, 2016, No. 03, Page(s).

[7]. Sun Bei. Analysis of the Impact of Economic Openness and Fertility Rate on Female Employment in China: Based on 1993-2011 CHNS Data[J]. Journal of Shandong University of Finance and Economics, 2019, 08. Online Publication Date: 2019-07-16 to 2019-08-15.

[8]. Xinhua. China to reduce the gap in employment rates and income between men and women[J]. World of Labor Security, 2011, 09: 10.

[9]. He Meng. International Labour Organization: Women’s Re-employment Numbers Post-pandemic Will Be Lower Than Men’s[N]. Global Women’s Perspective, 2021-07-28.

[10]. Qing Research Institute. Under the Pandemic: Significant Impact on Female Employment[R]. Qing Research Institute Series Report, 2021, No.3, June 2021.

[11]. Yang Lihong^1, Zhou Wenji^2. Rising or Declining? - An Analysis of the Reasons for the Increase in the Number of Employed Women in the US during the Great Depression[J]. Times of Vicissitudes, 2008, 05.

[12]. Kuang Aiping. The Impact of Female Employment on China’s Economic Development[J]. Modernization of the Marketplace, 2005, 26: 193-194.

[13]. Wang Sufeng. Evolution and influencing factors of the employment rate of graduates from regular universities in China from 2003 to 2010[J]. Journal of Wanxi University, 2014, 01: 54-57.

[14]. Zhou Yuzhong. Population aging, economic growth, and women’s employment: Empirical evidence based on cross-national panel data. Journal of Jingchu Institute of Technology, 2020, 03: 70-77.

[15]. Zhu Yi. Has technological progress exacerbated the gender employment gap?[J]. Modern Finance & Economics (Journal of Tianjin University of Finance and Economics), 2020, 10: 97-114.