1. Introduction

Understanding and exploring the main factors affecting the employment rate is crucial to formulating effective policies and promoting economic growth.

According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s definition of the employment rate, the employment rate measures the proportion of employees in the population of working age (15-64 years), i.e. the ratio of the number of employed persons to the population. The International Labor Organization (ILO) defines a person as employed when he or she has worked more than one hour in a "gainful" position during the most recent week [1].

The employment rate measures an economy’s ability to create jobs and is therefore often used in conjunction with the unemployment rate to assess the state of the labor and employment market. In general, three indicators are used to describe the supply of labor in the labor market: the labor force participation rate, the employment rate, and the unemployment rate. Distinguished from the other two indicators, the employment rate refers to the proportion of people with jobs to the total working age population. The labor participation rate, on the other hand, is the proportion of the economically active population out of the total working-age population; and the unemployment rate is the proportion of the economically active population without a job. According to the above definitions, there is a constant relationship between the three: \( U+O=T-E \) , where stands for the unemployed, for those who have dropped out of the labor market, for the working-age population and for the employed.

Now that the Corona epidemic is over, the market is affected to varying degrees in each country and the employment rate situation remains to be seen [2]. The study used regression analysis, correlation analysis and other methods to study the various factors affecting the changes in the employment rate and to give explanations.

2. The influence of political factors on the employment rate

The employment situation in Canada is now stabilizing, and the impact of the epidemic on the job market has recovered, but the up-and-down movement remains volatile. Figure 1 shows the change in employment from January 2013 to June 2023.

Figure 1: Employment rate of Canada (2013-2023)

From Figure 1, it can be seen that before March 2016, the employment rate had a significant peak period from May to August each year, which was clearly caused by the local wave of graduates looking for jobs.

And from 2016 onwards, the fluctuation of the employment rate is greatly reduced and shows a steady upward trend, the causes of this trend research speculates that there are two, the first one is in 2013 the Canadian government enacted the extension of compulsory education bill; the second one is talent admission policy of Canada.

The extension of compulsory education has led to an increase in the number of high-end talents, which in turn promotes the level of science and technology in Canada, and ultimately leads to the emergence of more industries and an increase in the employment rate. Secondly, developed countries generally take the tertiary industry as the main pillar industry, and Canada is no exception. More high-end talents conform to such a development trend, and the tertiary industry has high requirements for the education level of laborers. The extension of compulsory education makes the laborers have the knowledge level that meets the demand of employers in the tertiary industry, and so it can eventually make the employment rate increase. In addition, education is also an industry in itself. Compulsory education increases the demand for teachers in schools, creating more jobs, which is also a reason for the increase in the employment rate [3].

Talent admission policy has always been a way for developed countries to attract overseas talents by relying on their high living standards, favorable economic conditions and high education levels. Such a policy increases the level of science and technology in the country and translates into productivity and employment [4].

The employment rate curve fell sharply in April 2020 due to the home segregation policy enacted by the Canadian government in March, where most businesses stopped working and hiring. But employment soon climbed again, and the study attributed this to the high level of communications in Canada itself and characteristics of the tertiary sector, with Wi-Fi penetration so high in urban areas that many companies were able to organize home-based work and home-based interviews. Therefore, the home quarantine brought about by the new crown epidemic did not cause the same serious damage to Canadian companies as those in other lagging countries.

The Canadian government instituted a liberalization of the epidemic in March 2021, and the employment rate quickly returned to the average level of over 62%. This shows that during the home isolation period of the epidemic, Canadian educational institutions are still operating normally, and it also shows that Canadian businesses quickly returned to normal after the epidemic was unblocked. This is all due to Canada’s advanced education system and strong tertiary industry [5].

3. The influence of economic factors on the employment rate

Figure 2: Employment rate and GDP (2013-2023)

Table 1 is the regression analysis between the employment rate and GDP from January 2013 to June 2023, and the r square of the results of the regression analysis is 0.0879. It can be clearly seen that the growth of GDP has an important role in promoting the growth of the employment rate, and there is a certain consistency between the trend of GDP and the trend of the employment rate, as Figure 2 presents.

Table 1: Results of the regression analysis (GDP)

Coefficients | P-value | |

Intercept | 52.77868529 | 8.29E-44 |

X Variable | 4.403312858 | 0.0007879 |

Table 2 shows the regression analysis between the employment rate and the inflation rate, and the \( r \) square of the results of the regression analysis is 0.1453. The timeframe of Table 2 is consistent with Figure 3. Inflation in Canada has been fairly stable, with only one period of moderate inflation greater than 6% between March 2022 and December 2022, and the rest of the decade being healthy inflation.

Figure 3: Employment rate and Inflation (2013-2023)

Table 2: Results of the regression analysis (Inflation)

Coefficients | P-value | |

Intercept | 60.42597561 | 1.4E-178 |

X Variable | 0.318131174 | 1.06E-05 |

However, during the period of moderate inflation, the employment rate of Canada remained unaffected at around 60%, so the study hypothesizes that such moderate inflation was due to a brief overheating of the economy as a result of increased government spending.

Developed countries like Canada have a relatively strong capacity for science and technology innovation, a factor that can be a contributing factor to the stabilization of the employment rate in Canada. In addition, science and technology innovation also has a reciprocal effect on GDP growth, which has a significant impact on the employment rate in the long run [6].

4. The influence of social factors on the employment rate

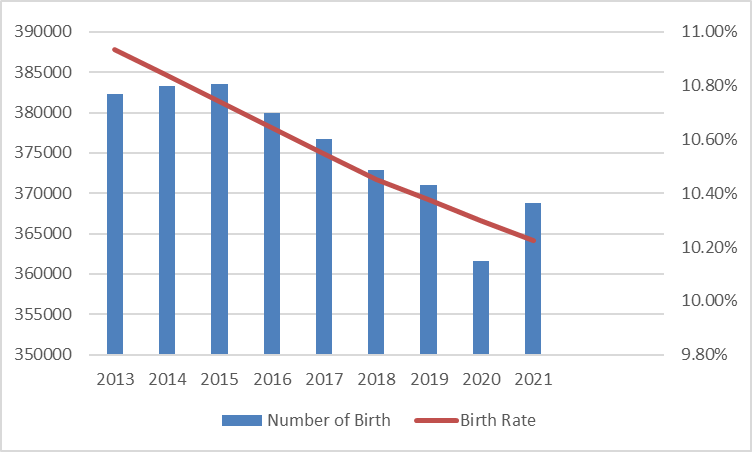

4.1. Birth rate

In this research, the average annual employment rate, number of births, tertiary sector distribution and number of immigrants from 2013 to 2021 were chosen as the subjects of the study. It was found that the birth rate and the average annual employment rate have a high correlation, while the other two correlation values are lower. Although a low birth rate reduces competition for jobs, the impact of a low birth rate is still predominantly negative for Canada, which is already not very densely populated and where the pressure to compete for jobs is already low. The birth rate directly affects the number of newborns, and if the birth rate stays low, it could lead to a contraction of industries such as education, baby products, and children's health care, indirectly affecting the employment rate [7].

Table 3: Results of the correlation analysis

Number of Birth | Tertiary sector Distribution | Number of Immigrants | |

Correlation | 0.71 | -0.4 | 0.1 |

In addition, developed countries like Canada generally face low birth rates. A low birth rate will have a direct impact on the size of the population, thus leading to a reduction in the base of size of the working population. In this case, even if there is a mature education system and good employment opportunities, it may lead to a situation where the employment rate is high but the labor force is insufficient [8].

Figure 4: Number of birth and Birth rate (2013-2021)

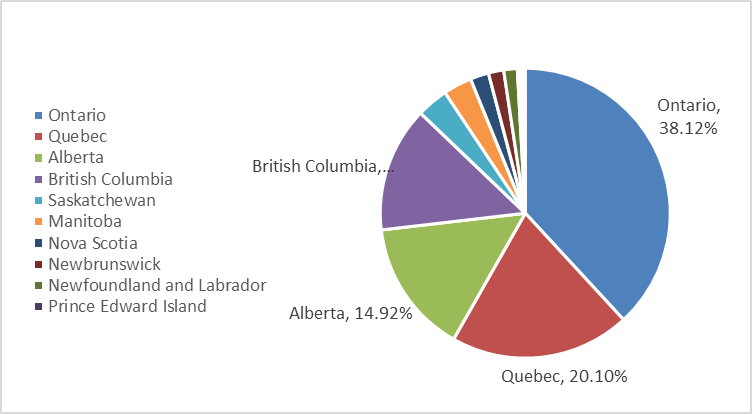

4.2. Unbalanced development

Figure 5: GDP share of Canadian provinces (2022)

The degree of economic development of Canadian provinces is seriously unbalanced, as shown in Figure 5. All but Ontario, Quebec, Alberta and British Columbia account for no more than 5% of GDP, and the GDP share of four provinces has exceeded 85% of the national GDP. This may be due to the fact that excessively cold weather in some provinces has rendered some of the provinces unsuitable for economic development and habitation. Such a situation may cause talents from economically backward provinces to be reluctant to take up employment in their own provinces and seek employment in economically large provinces instead. Such a situation may lead to fierce competition in the job market of the economically large provinces and an oversupply of jobs, thus leading to a surplus of talents. While the economically backward provinces have a shortage of labor, making it difficult for industries to develop, and economic development is caught in a vicious circle.

In fact, Canada admits more than 250,000 immigrants every year, and in 2022 the number of immigrants will even be close to half a million. This move can make up for the country's population shortage and promote economic development. According to the immigration policy of Canada, the quality of immigrants, and asset requirements are not low, and there is a strict review of the legality of income. On the one hand, it can ensure the stability of the quality of immigrants, and on the one hand, it can also ensure that the country's security order [9][10].

5. The influence of technological factors on the employment rate

Overall, the job market in Canada, although affected by the Corona epidemic, has now returned to normal levels and remains stable. Developed countries such as Canada have a strong foundation in science and technology innovation. This characteristic plays a vital role in stabilizing the employment rate within the country. Furthermore, it is observed that science and technology innovation also reciprocally impacts the growth of the gross domestic product (GDP) in the long run.

Thus, it can be said that Canada's proficient capacity for science and technology innovation not only contributes to the stability of employment but also to the sustainable economic development of the nation.

Figure 6: Percentage of industries in Canada (2008-2018)

The Canadian government should focus on minimizing the economic gap between the provinces by improving infrastructure and providing incentives for industrial development, so that employed people are more willing to go to other provinces for employment and broaden the job market. Secondly, the low birth rate has always been a difficulty faced by developed countries. The government can encourage births and at the same time take advantage of the country's favorable conditions to attract more high-quality immigrants, so as to fill the shortage of labor force with the population base.

6. Conclusion

This paper examines the four perspectives of politics, economy, society, and technology that influence the employment rate situation in Canada and concludes that the continued high GDP, stable and healthy inflation, a well-developed tertiary sector and immigration and employment policies have contributed to high employment rate, but low birth rates and regional imbalances may limit further gains. However, for developed countries like Canada, where employment rates tend to stabilize under normal circumstances, a breakdown of employment by industry sector may be more valuable to study. This paper does not analyze the various industry sectors of the job market on a segmented basis, which is somewhat one-sided.

Also, the development and application of artificial intelligence (AI) technology has impacted the job market in recent years, which may also be related to the fluctuation of employment rates from 2023. Therefore, future research on employment rate may focus on examining industries that are more affected by AI technology.

References

[1]. OECD (2016), "Employment rates", in OECD Factbook 2015-2016: Economic, Environmental and Social Statistics, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/factbook-2015-49-en.

[2]. Bluedorn, J., Caselli, F., Hansen, N., Shibata, I., & Tavares, M. M. (2023). Gender and employment in the COVID-19 recession: Cross-Country evidence on “She-Cessions.” Labour Economics, 81, 102308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2022.102308.

[3]. Blöndal, S., S. Field and N. Girouard (2002), "Investment in Human Capital Through Post-Compulsory Education and Training: Selected Efficiency and Equity Aspects", OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 333, OECD Publishing, Paris,

[4]. Kerr, S. P., Kerr, W. R., Ozden, C., & Parsons, C. (2016). Global talent flows. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(4), 83–106. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.30.4.83.

[5]. Gallacher, G., & Hossain, I. (2020). Remote Work and Employment Dynamics under COVID-19: Evidence from Canada. Canadian Public Policy-analyse De Politiques, 46(S1), S44–S54. https://doi.org/10.3138/cpp.2020-026.

[6]. Phillips, A. W. (1962). Employment, Inflation and Growth1. Economica, 29(113), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0335.1962.tb00001.x.

[7]. Bernhardt, E. (1993). Fertility and employment. European Sociological Review, 9(1), 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.esr.a036659.

[8]. Sleebos, J. (2003). Low fertility rates in OECD countries: facts and policy responses. OECD Labour Market and Social Policy Occasional Papers. https://ideas.repec.org/p/oec/elsaaa/15-en.html.

[9]. Hiebert, D. (2006). WINNING, LOSING, AND STILL PLAYING THE GAME: THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF IMMIGRATION IN CANADA. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie, 97(1), 38–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9663.2006.00494.x.

[10]. Frank, K. (2013b). Immigrant Employment success in Canada: Examining the rate of obtaining a job match. International Migration Review, 47(1), 76–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12014.

Cite this article

Chen,C. (2024). Analysis of the Main Factors Affecting Employment Rates in Canada. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,59,190-196.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Financial Technology and Business Analysis

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. OECD (2016), "Employment rates", in OECD Factbook 2015-2016: Economic, Environmental and Social Statistics, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/factbook-2015-49-en.

[2]. Bluedorn, J., Caselli, F., Hansen, N., Shibata, I., & Tavares, M. M. (2023). Gender and employment in the COVID-19 recession: Cross-Country evidence on “She-Cessions.” Labour Economics, 81, 102308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2022.102308.

[3]. Blöndal, S., S. Field and N. Girouard (2002), "Investment in Human Capital Through Post-Compulsory Education and Training: Selected Efficiency and Equity Aspects", OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 333, OECD Publishing, Paris,

[4]. Kerr, S. P., Kerr, W. R., Ozden, C., & Parsons, C. (2016). Global talent flows. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(4), 83–106. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.30.4.83.

[5]. Gallacher, G., & Hossain, I. (2020). Remote Work and Employment Dynamics under COVID-19: Evidence from Canada. Canadian Public Policy-analyse De Politiques, 46(S1), S44–S54. https://doi.org/10.3138/cpp.2020-026.

[6]. Phillips, A. W. (1962). Employment, Inflation and Growth1. Economica, 29(113), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0335.1962.tb00001.x.

[7]. Bernhardt, E. (1993). Fertility and employment. European Sociological Review, 9(1), 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.esr.a036659.

[8]. Sleebos, J. (2003). Low fertility rates in OECD countries: facts and policy responses. OECD Labour Market and Social Policy Occasional Papers. https://ideas.repec.org/p/oec/elsaaa/15-en.html.

[9]. Hiebert, D. (2006). WINNING, LOSING, AND STILL PLAYING THE GAME: THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF IMMIGRATION IN CANADA. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie, 97(1), 38–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9663.2006.00494.x.

[10]. Frank, K. (2013b). Immigrant Employment success in Canada: Examining the rate of obtaining a job match. International Migration Review, 47(1), 76–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12014.