1. Introduction

The definition of a gig economy is ambiguous - it is often associated with the terms “Sharing Economy” or “Freelance Economy” - and they do have many similarities with each other, the term “gig economy” that is referred to in this paper will refer to the industry associated with platforms, typically digital ones, that allow independent freelancers to connect with individuals or businesses for short-term services or asset-sharing [1]. Freelancers in the gig economy work as independent contractors, rather than as full-time employees of any one employer. They set their rates for the services that they provide and handle their benefits, working hours and taxes [2].

Nevertheless, gig workers are playing an important role in various industries, and their contribution is only expected to be more significant. In this paper, we aim to define the gig economy and evaluate some of the challenges it currently faces or will expect to face in the future, and finally, present a case study on integrating the gig workforce into the traditional economy sustainably and effectively that avoids common gig economy challenges.

2. Overview of the Gig Economy

The global Gig Economy in 2018 generated $204B in Gross Volume, and in 2023 this number is expected to be around $455B [1]. This rapid growth could be attributed to many factors such as evolving societal attitudes around P2P sharing and increasing digitization rates in developing Countries.

2.1. Gig Workers with Different Motivation

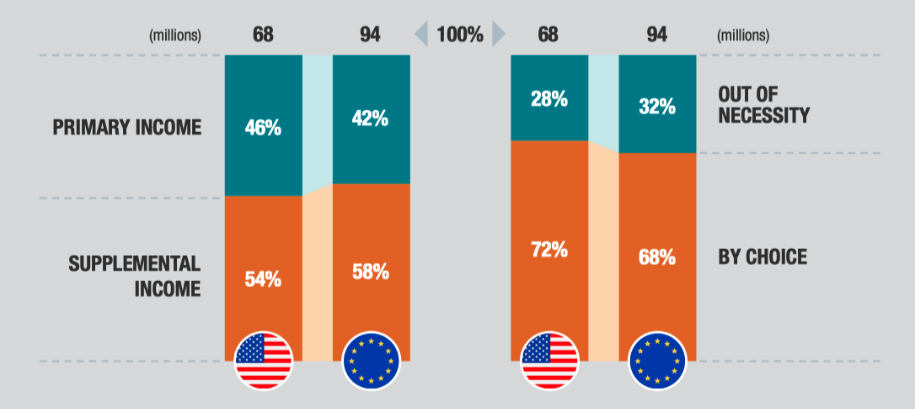

Out of the 162 million gig workers, nearly 86% do gig jobs out of preference or to get a side job. Only 14% do a gig job out of necessity to make a living [3]. People who choose to do a gig job out of necessity most likely choose to partake in the gig economy because of potential language or education barriers - many gig jobs, such as Uber driving or being a babysitter or a nanny do not require certain skills that are required for a “conventional” job. For them, independent work is simply better than the alternative of unemployment or an undesirable traditional job. Many are not in temporary roles by choice; they would prefer the perceived stability of a traditional job. Furthermore, people who actively chose their working style reported greater satisfaction than those who felt forced by circumstance. This creates the first inefficiency in the gig economy: part-time employment is not satisfactory to achieve the malevolent success of deeds to promote good outcomes, for example, sustained worker productivity and attitudes towards work. [4]. Figure 1 shows that there is a slight difference in this segmentation between the US and EU, but overall, most gig workers do it as supplemental income and do it by choice.

Figure 1: Volumetric difference between streams of income for gig workers [3].

2.2. Dependence on Digital Solutions

The gig economy is heavily associated with digitization - the largest aspect of gig work, transportation, which makes up 58% of all gig income volume, is done almost entirely online - with apps like Uber, Lyft, and DoorDash being at the frontier of transportation gig work. However, digitalization rates in the gig economy are actually very low, even showing a decline over the years. In 2016, 15% of gig workers used digital platforms and in 2018, only 8% did. This number should, theoretically, go up because of the increasing omnipotence of technology in our lives and the workspace today. This may be because of the unequal distribution of work in the gig economy - out of the 162 million gig workers, 150 million of them are workers who provide labor - and only 6% of them use digital platforms, whereas 63% of workers who sell goods use digital platforms, but there are only 21 million of them [3]. This decrease in digitalization may be attributed to an increase of workers who provide labor, especially those in third world countries where technology is not as developed. This lack of digitalization brings us the second disadvantage to the gig economy: its lack of impact in developing countries where digitization is not prevalent. Gig work without digitalization is often ineffective, such as babysitting, cab driving (without an app), and delivery jobs (without digital courier services). Digitalization brings a great increase in efficiency to gig jobs, but since most developing countries do not have sufficient digitalization to implement the scale of many digital gig jobs, gig jobs there are very inefficient, compared to developed countries [5].

3. Major Segments of Gig Economy and Their Challenges

There are four main segments of the gig economy, each facing its respective challenges.

3.1. Transportation-based Services

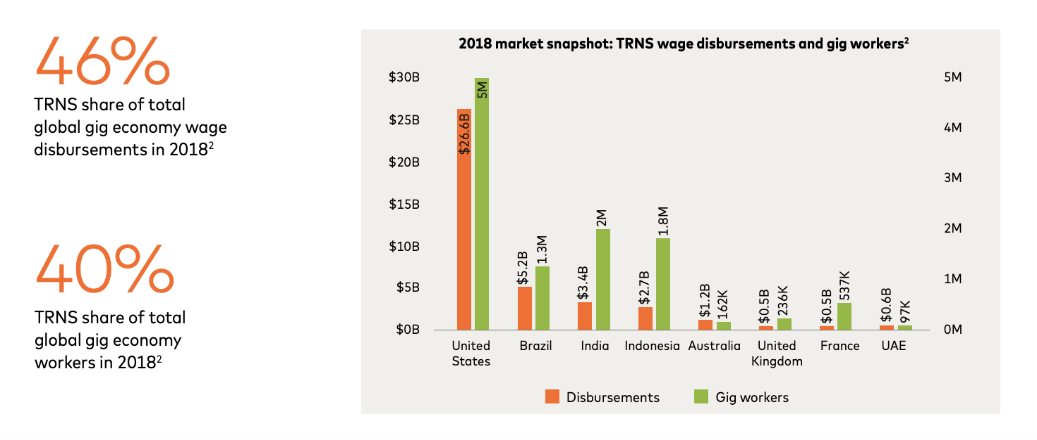

Transportation-based services are defined as “the sector that facilitates the transportation of people, goods and food,” with ridesharing, food delivery, goods delivery, and carpooling being its main four segments. Out of these four, ride-sharing - companies like Uber and Lyft - are the most established, with a $55.7B disbursement as of 2018 with 90% of Transport based services being related to ride-sharing. Figure 2 shows us that although in 2018, most TRNS wage disbursements occurred within the United States, developing countries with high populations, such as Brazil and India, also have substantial disbursements. However, this poses another challenge to the gig economy. Developing countries often lack digitalization, and in countries like India, half of India's population lacks internet access, and just twenty percent of Indians know how to use digital services [6]. This means that a significant portion of people in rising markets are unable to access gig services. This is especially harmful for countries like Brazil which have a huge land mass but an underdeveloped public transit system(s) [7]. There may be a large demand for TRNS services in these areas, but they are also among the least digitized parts of the world, making implementing proper transportation-based services almost impossible [8].

Figure 2: TRNS global wage disbursements [9].

3.2. Professional Services

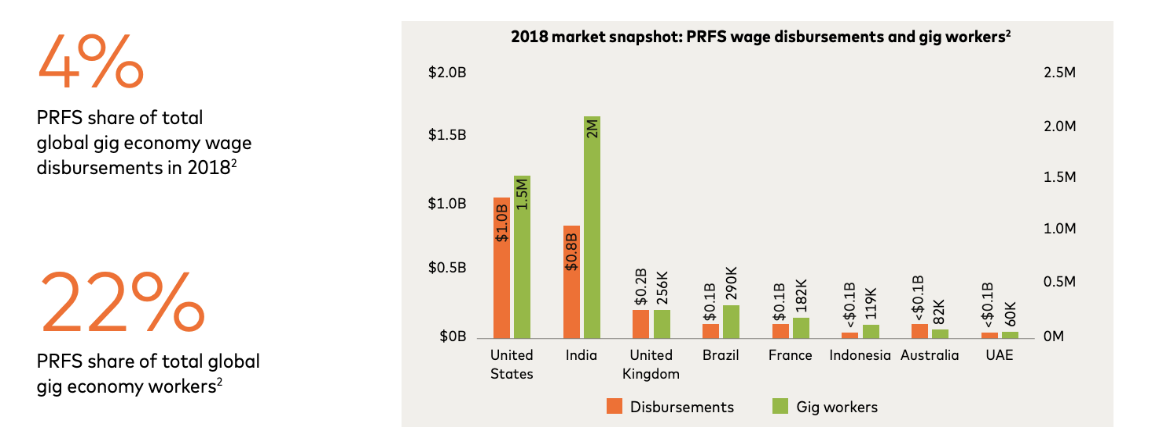

Professional work is defined as “the sector that connects gig workers with businesses to complete high-skilled projects, professional services (PRFS) cover a broad array of skilled industries such as graphic design, tech/coding, writing, translation, and administrative work.” Professional work is a global sector, with key companies such as Upwork, Freelance, and Guru, which operate across several regions. Figure 3 shows us PRFS is unique because it accounts for more than one-fifth of active global gig workers but less than 5 percent of global disbursement flows. This is because of geographical disparities. People find contractors in low-income countries who are willing to work for cheap, as PRFS doesn’t require individuals to be in the same geographical proximity to do a job. Therefore, India alone accounts for 14 per cent of global PRFS disbursement volume while supplying more than one-fifth of the active global gig workers in this sector [9]. However, the development of AI in this sector is posing a threat to professional service workers [10]. Gig workers are primarily utilized to save time for corporations to reallocate time and resources for strategic thinking and other areas of business planning [11]. AI offers a free, faster, more accessible, and more customizable alternative to professional service gig work, such as coding, graphic design, or copywriting. AI’s appearance will lower the need for gig work, and greatly up the standards in terms of quality for professional services created by humans [12].

Figure 3: PRFS global wage disbursements [9].

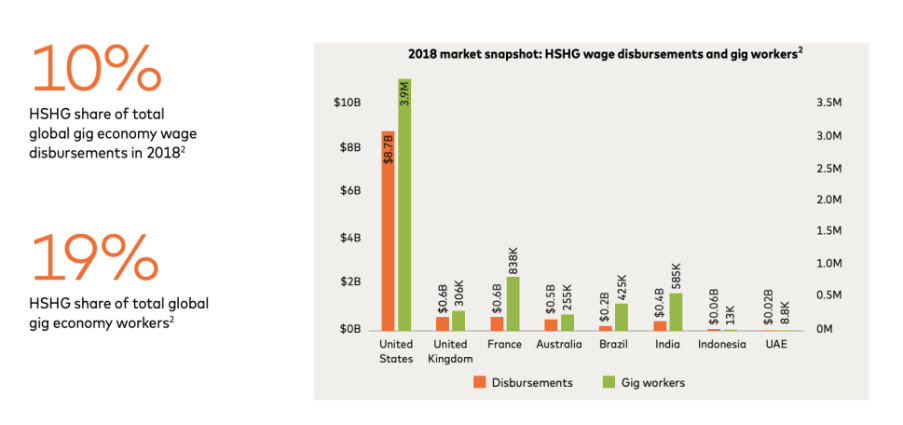

3.3. Household Services and Handmade Goods

This sector primarily contains “services and goods including micro-businesses selling homemade crafts and on-demand household services such as babysitting, plumbing, pet care and tutoring.” HSHG - with key companies such as Etsy, care.com, and TaskRabbit - accounted for $14B in disbursements to 8.1M gig workers in 2018 and is a relatively new platform - more than half of its platforms were created in just the last 5 years. Figure 4 shows us that HSHG is primarily a gig segment for wealthier countries and consumers, with the US alone driving 62% of the total volume. However, like the developments of other gig sectors, many platforms are beginning to target emerging markets in regions such as Southeast Asia, especially India [9].

Figure 4: HSHG global wage disbursements [9].

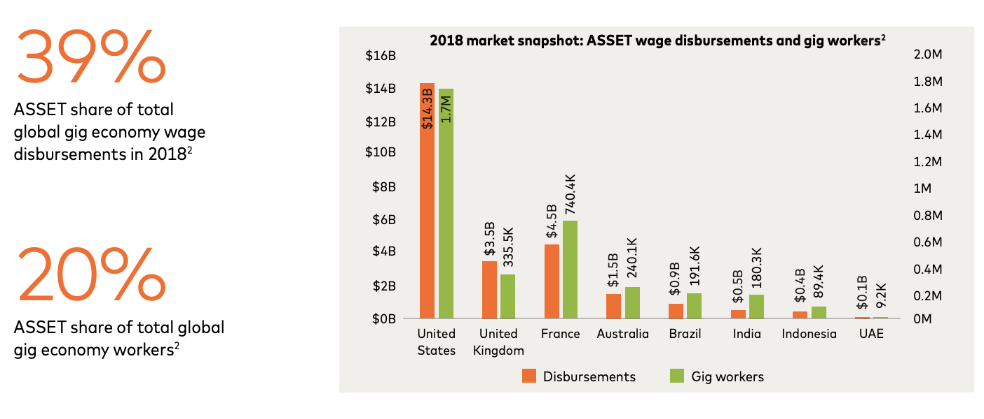

3.4. Asset Sharing Services

Asset sharing platforms - such as Airbnb, booking.com, or drivy - facilitate short-term, person-to-person rentals of an asset owner’s (or gig workers’) personal property - such as houses, cars, boats, or even parking spaces. People under this category typically use this to garner supplementary income rather than a full-time job. Asset sharing accounted for $52.7B in disbursements to approximately 8.6M gig workers in 2018, and Figure 5 shows us this service is primarily for wealthier countries. Home-sharing contributed nearly all (92 per cent) of the total disbursement volume [9].

Figure 5: ASSET wage global wage disbursements [9].

4. The Future Outlook of Integrating Gig Model to Mainstream Businesses

To fully unleash the potential of this increasing group of talents, it’s important for business leaders to revisit their talent-acquiring strategy. In this section, we will discuss the prospect of this shift.

Gig workers are treated as freelancers, meaning they do not get provided benefits such as paid time off or health and workers compensation insurance [13]. Therefore, many people, especially those of the highest credentials and skill levels, are hesitant to enter gig jobs, leaving people of either low or average skill levels in gig jobs. Although the gig economy is growing, the amount of high-skill gig workers is not, because of the unappealing nature of gig work. Because of the “lower quality” nature of gig workers, the gig economy has a “bad reputation” among consumers and firms as their quality of work is seen as “low/lower” than traditional workers, creating distrust that corporations have about “renting” gig workers as an aid to a temporary workspace [11].

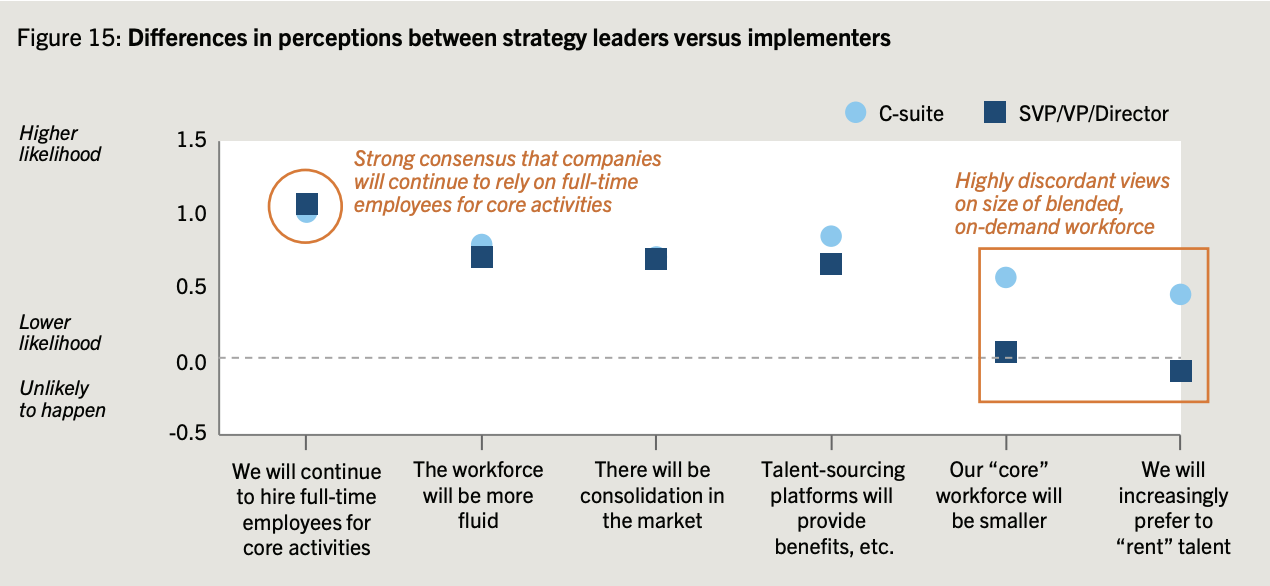

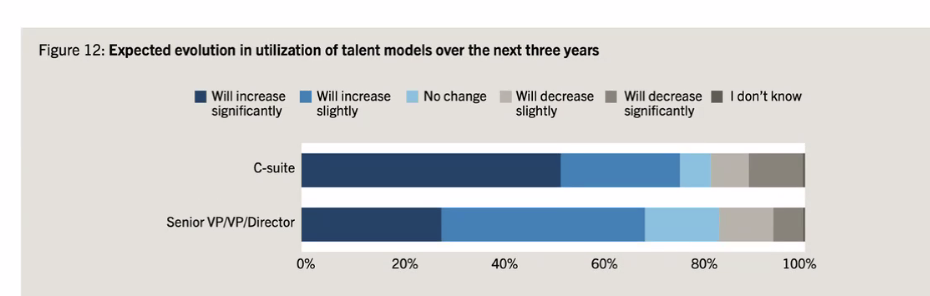

Figure 6 shows us that although chief executives seem very idealistic about the future of gig work, hiring managers, senior VPs and directors do not seem very confident in the expected evolution in the utilization of talent models over the next three years. Experience in a gig job increases the call-back rate from employers compared to unemployment, but not as much as similar experience in the traditional labor market. More specifically, gig experience improves the contact employment rate by around 2 percentage points (or 11%) compared to unemployment, while the impact of traditional experience is about twice as large [14]. This reflects the inherent distrust towards gig workers: gig workers are cheaper and more convenient to rent/hire/train than traditional employees, but hiring managers are still doubtful because of the “high” associated risk of failure [11].

Figure 6: C-suite vs SVP/VP/Directors’ view on outsourcing gig talent [11].

5. Case Study - A Solution to Integrate Gig Model in Call Center Operation

The pandemic has left behind a change in the general attitude and sentiment towards the style of working. Whereas previously, “traditional” jobs were seen as office jobs, the pandemic proved that working remotely and digitally, along with working in hours that were employee-determined, could also yield similar, if not greater, amounts of productivity [15].

However, this “style of working can be brought to an even greater extent. Gig work has always been typically remote, self-determined work. A foreseeable growing trend among employers is to hire gig workers as a supplement to their “original” workforce, and one industry that could greatly benefit from this style of working is the call center industry.

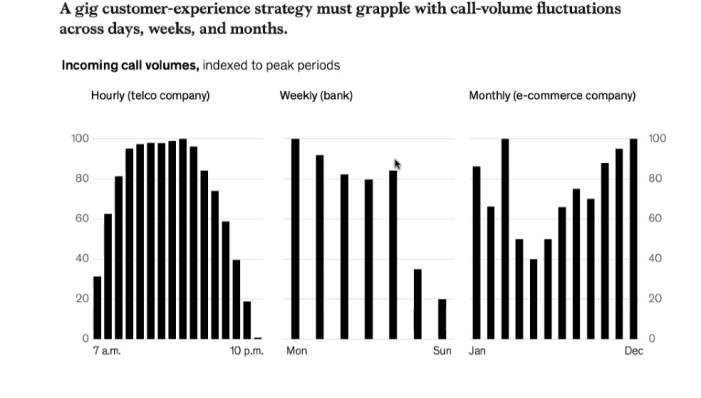

Figure 7: Fluctuations in the call center industry [17].

Figure 7 shows us that the call center industry faces large fluctuations in call volume monthly, weekly, and even hourly. Because of this, at periods of high influx of calls, call center agents find themselves dealing with periods with an overflow of long queues, and at periods of low influx of calls, many agents find themselves idle with no customers calling in. Many large corporations are well-equipped to handle this, as they have an adequate and well-trained team that is equipped to handle large fluctuations in call volumes, but many small businesses with a small customer service team often find themselves frequently dealing with complaints from customers and overworked staff. Furthermore, businesses may face losses from either paying extra for employees during peak season or losses in customer satisfaction due to overworked employees [16].

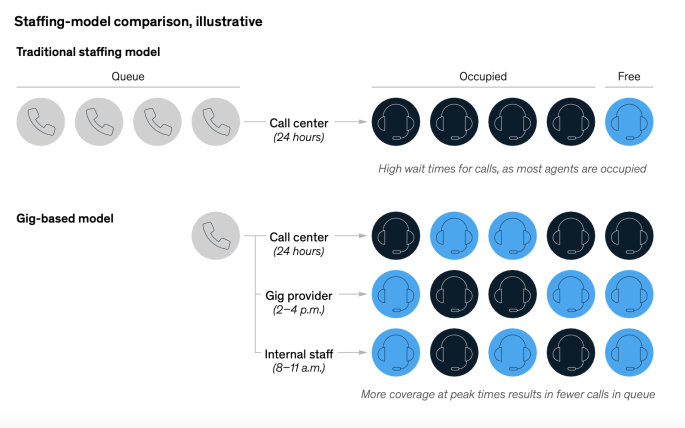

Flexible staffing—the use of external talent from outsourcing providers or independent freelancers— has been a staple of customer service for decades. Businesses, especially essential ones such as banks, need to have their phone lines open 24/7. Therefore, they outsource their needs overseas and hire foreign operators to handle clients’ concerns. However, as shown by Figure 8, this strategy was not operated on a large-scale pre-pandemic because of concerns over the lack and productivity and biases towards the traditional working sentiment. But now this model has proven efficient, the customer service industry, especially the call center, can utilize it for maximum efficiency.

Figure 8: C-suite vs SVP/VP/Directors’ view on gig talents’ presence in the future workspace [11].

As illustrated by Figure 9, whereas traditional models utilize a “one-line” type of service, the recommended model is the gig-based model. In addition to the traditional model, there will also be gig teams on standby. Where, during peak hours, the customer service calls will get redirected to the gig workers in charge of backing up that shift, and during hours of low traffic, those gig workers will be “off-duty.” This may be done with statistical analysis and modeling to show when and what the optimal protection overflow and idle times are.

Figure 9: Hypothetical model for gig staffing model [17].

Like DoorDash or Uber, there will be a platform for call-center gig agents to register on. Then, the gig agent will choose the skill(s) that they are the most comfortable in with assisting others, and when it is their shift, overflow calls will be routed through the app to the gig agent.

What's more, because this model does not require many resources, talent sourcing is easier. Unlike other common gig jobs, like the transportation services industry where workers need to own a phone with consistent cell service, which may be hard to obtain in rural areas, and a car, which may be a large financial burden for some, call center staffing only requires a phone, which makes talent sourcing easier. Furthermore, not only will call center staffing give people in rural areas the chance to get a job, but it also changes the negative view many corporations have of the gig economy. Once implemented and monitored, if it has a positive effect, corporations may be more trustworthy of the gig economy, and rent talent from the gig economy for other parts of the business stream. Compared to the traditional way of sourcing employees, which only benefits employees in the businesses’ local area, not only can renting gig employees benefit rural workers but also benefit the business by hiring better labor.

Unlike other gig sectors, the customer service sector is not going to be impacted by AI - instead, the industry can properly utilize AI to its benefit. For example, AI-powered chatbots can provide real-time assistance to customers, reducing the number of unnecessary calls, and simultaneously reducing the queue time. Furthermore, AI can be used as a training tool. Instead of supervisors or businesses’ customer service departments providing training to gig workers, AI technology can help provide necessary and customizable training to gig workers, which helps businesses save time and capital. AI can also be used to provide feedback: It can analyze call data in real time, providing supervisors with instant insights into agent performance and customer satisfaction. This data is especially important with gig workers, who may be less familiar with the routine workings of a customer service call.

6. Conclusion

There are many advantages to using the gig model. First, the size of the gig economy makes talent sourcing easier. Because the pandemic caused lots of people to work from home, lots of workers have adapted their skill sets to match the needs of the digital age, making it easy for recruitment. It is estimated in 2018 that 36 per cent of US workers had a gig work arrangement in some capacity, including independent contractors, online-platform workers, contract-firm workers, on-call workers, and temporary workers [17].

Second, using gig workers can help overcome geographic limits to talent sourcing— it offers efficiencies by reducing the need for physical infrastructure, allowing costs to be scaled more closely to output requirements. Not only can potential gig employees have a higher skill level because there is a broader talent pool to source from, but costs will simultaneously be reduced.

Third, there is also a benefit for gig workers. If implemented, workers, for their part, get the opportunity to work with multiple client companies simultaneously, which can translate into broader exposure, potentially higher earning potential, and greater scheduling flexibility. Furthermore, it also allows for the gig workers to network and get into a better career.

Lastly, the customer experience improves. Apart from having a reduced queue time, companies can also enhance the customer experience by enlisting specialized talent. For example, branch and store staff can field general inquiries and requests, while for more technical topics, companies can bring on external gig workers: professional gamers, for instance, could be engaged to handle calls related to gaming- hardware recommendations.

There are two main limitations of this strategy. First, there are concerns over how traditional metrics, oversight, and performance-management standards don’t always translate to gig-worker models. As gig workers may not have been as extensively trained as in-business call center workers, the quality may be inconsistent.

Second, there will be concerns over digital safety. The customer service industry often deals with a large amount of private information about a customer - their identity, bank details, etc. - as they need information about the customer to solve the customer's problem. However, since gig outsourcing is not technically part of the company, there will be information about their unregulated dealings with private client information, especially sensitive information such as bank details.

Finally, it may be hard to train and develop proper skills for the outsourced gig callers. Every company has their own distinct set of values that they embody. Since the customer service industry is one of the most upfront and direct-to-consumer industries, and often, since the customer industry is what defines a company’s public image, companies must make sure to extensively train outsourced gig callers.

References

[1]. Mastercard. The Global Gig Economy: Capitalizing on a ~$500B Opportunity. May 2019.

[2]. Donovan, Sarah A., David H. Bradley, and Jon O. Shimabukuru. "What does the gig economy mean for workers?." (2016).

[3]. Manyika, James, et al. Independent-Work-Choice-necessity-and-the-gig-economy. McKinsey Global Institute, 2016.

[4]. Cavaliere, Luigi Pio Leonardo, et al. "The Impact of Part-Time and Full-Time Work on Employees' Efficiency the Importance of Flexible Work Arrangements." Turkish Online Journal of Qualitative Inquiry 12.7 (2021).

[5]. Liu, Kai , et al. “Examining the Role of Digitalization and Gig Economy in Achieving a Low Carbon Society: An Empirical Study across Nations.” Frontiers in Environmental Science, vol. 11, 12 May 2023.

[6]. Mullick, Maitrayee, and Archana Patnaik. “Pandemic Management, Citizens and the Indian Smart Cities: Reflections from the Right to the Smart City and the Digital Divide.” City, Culture and Society, Aug. 2022, p. 100474, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2022.100474. Accessed 24 Aug. 2022.

[7]. Laska, Alexander, and Rayla Bellis. “Rural Communities Need Better Transportation Policy – Third Way.” Www.thirdway.org, 13 Sept. 2021, www.thirdway.org/memo/rural-communities-need-better-transportation-policy.

[8]. Porru, Simone, et al. “Smart Mobility and Public Transport: Opportunities and Challenges in Rural and Urban Areas.” Journal of Traffic and Transportation Engineering (English Edition), vol. 7, no. 1, Feb. 2020, pp. 88–97, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtte.2019.10.002. Accessed 13 Apr. 2020.

[9]. Mastercard. THOUGHT LEADERSHIP Fueling the Global Gig Economy How Real-Time, Card-Based Disbursements Can Support a Changing Workforce. Aug. 2020.

[10]. Lewis, Edward, et al. Year in Review INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION of CLAIM PROFESSIONALS. Insurance Law Global, 18 Sept. 2020.

[11]. Fuller, Joseph B., et al. "Building the on-demand workforce." Published by Harvard Business School and BCG (2020).

[12]. Wach, Krzysztof, et al. “The Dark Side of Generative Artificial Intelligence: A Critical Analysis of Controversies and Risks of ChatGPT.” Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, vol. 11, no. 2, 1 Jan. 2023, pp. 7–30, https://doi.org/10.15678/eber.2023.110201.

[13]. De Stefano, Valerio. "The rise of the just-in-time workforce: On-demand work, crowdwork, and labor protection in the gig-economy." Comp. Lab. L. & Pol'y J. 37 (2015): 471.

[14]. Adermon, Adrian, and Lena Hensvik. “Gig-Jobs: Stepping Stones or Dead Ends?” Labour Economics, vol. 76, June 2022, p. 102171

[15]. Parker, Kim, et al. “How Coronavirus Has Changed the Way Americans Work.” Pew Research Center, 9 Dec. 2020, www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2020/12/09/how-the-coronavirus-outbreak-has-and-hasnt-changed-the-way-americans-work/

[16]. Pichitlamken, Deslauriers, L'Ecuyer and Avramidis, "Modelling and simulation of a telephone call center," Proceedings of the 2003 Winter Simulation Conference, 2003., New Orleans, LA, USA, 2003, pp. 1805-1812 vol.2, doi: 10.1109/WSC.2003.1261636.

[17]. Gupta, Vinay, et al. “A Gig-Economy Model for Customer-Service Operations.” McKinsey, 12 Oct. 2021, www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/operations/our-insights/an-on-demand-revolution-in-customer-experience-operations.

Cite this article

Wu,H. (2023). The Future of Work: A Comprehensive Study of the Gig Economy Beyond Low Labor-Value Added Jobs. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,64,112-120.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Financial Technology and Business Analysis

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Mastercard. The Global Gig Economy: Capitalizing on a ~$500B Opportunity. May 2019.

[2]. Donovan, Sarah A., David H. Bradley, and Jon O. Shimabukuru. "What does the gig economy mean for workers?." (2016).

[3]. Manyika, James, et al. Independent-Work-Choice-necessity-and-the-gig-economy. McKinsey Global Institute, 2016.

[4]. Cavaliere, Luigi Pio Leonardo, et al. "The Impact of Part-Time and Full-Time Work on Employees' Efficiency the Importance of Flexible Work Arrangements." Turkish Online Journal of Qualitative Inquiry 12.7 (2021).

[5]. Liu, Kai , et al. “Examining the Role of Digitalization and Gig Economy in Achieving a Low Carbon Society: An Empirical Study across Nations.” Frontiers in Environmental Science, vol. 11, 12 May 2023.

[6]. Mullick, Maitrayee, and Archana Patnaik. “Pandemic Management, Citizens and the Indian Smart Cities: Reflections from the Right to the Smart City and the Digital Divide.” City, Culture and Society, Aug. 2022, p. 100474, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2022.100474. Accessed 24 Aug. 2022.

[7]. Laska, Alexander, and Rayla Bellis. “Rural Communities Need Better Transportation Policy – Third Way.” Www.thirdway.org, 13 Sept. 2021, www.thirdway.org/memo/rural-communities-need-better-transportation-policy.

[8]. Porru, Simone, et al. “Smart Mobility and Public Transport: Opportunities and Challenges in Rural and Urban Areas.” Journal of Traffic and Transportation Engineering (English Edition), vol. 7, no. 1, Feb. 2020, pp. 88–97, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtte.2019.10.002. Accessed 13 Apr. 2020.

[9]. Mastercard. THOUGHT LEADERSHIP Fueling the Global Gig Economy How Real-Time, Card-Based Disbursements Can Support a Changing Workforce. Aug. 2020.

[10]. Lewis, Edward, et al. Year in Review INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION of CLAIM PROFESSIONALS. Insurance Law Global, 18 Sept. 2020.

[11]. Fuller, Joseph B., et al. "Building the on-demand workforce." Published by Harvard Business School and BCG (2020).

[12]. Wach, Krzysztof, et al. “The Dark Side of Generative Artificial Intelligence: A Critical Analysis of Controversies and Risks of ChatGPT.” Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, vol. 11, no. 2, 1 Jan. 2023, pp. 7–30, https://doi.org/10.15678/eber.2023.110201.

[13]. De Stefano, Valerio. "The rise of the just-in-time workforce: On-demand work, crowdwork, and labor protection in the gig-economy." Comp. Lab. L. & Pol'y J. 37 (2015): 471.

[14]. Adermon, Adrian, and Lena Hensvik. “Gig-Jobs: Stepping Stones or Dead Ends?” Labour Economics, vol. 76, June 2022, p. 102171

[15]. Parker, Kim, et al. “How Coronavirus Has Changed the Way Americans Work.” Pew Research Center, 9 Dec. 2020, www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2020/12/09/how-the-coronavirus-outbreak-has-and-hasnt-changed-the-way-americans-work/

[16]. Pichitlamken, Deslauriers, L'Ecuyer and Avramidis, "Modelling and simulation of a telephone call center," Proceedings of the 2003 Winter Simulation Conference, 2003., New Orleans, LA, USA, 2003, pp. 1805-1812 vol.2, doi: 10.1109/WSC.2003.1261636.

[17]. Gupta, Vinay, et al. “A Gig-Economy Model for Customer-Service Operations.” McKinsey, 12 Oct. 2021, www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/operations/our-insights/an-on-demand-revolution-in-customer-experience-operations.