1. Introduction

The Internet's integration into public life has made search engines indispensable tools for the public to access information and make informed choices. Consequently, search engines like Google and Baidu (China) have emerged as pivotal platforms for companies to execute product promotion campaigns and engage in business competition. The primary form of digital advertising involves enterprises purchasing advertising positions in search engine results for specific keywords to promote their publicity [1]. This form of keyword-based advertising aids in the expansion of brand awareness for companies, particularly among potential customers. However, some well-established companies may face competition from similar product companies utilizing this approach to capitalize on their market popularity. Therefore, these well-known trademark brands may face the risk of infringement.

Infringement disputes arising from such practices are not uncommon. This is a business practice on the verge of infringement. One typical case is Interflora Inc. v. Marks & Spencer Inc. [2]. A well-known British retailer, Marks & Spencer, procured a keyword advertisement from Google, a search engine company, to display its flower product website on the page when users search for Interflora, a renowned flower delivery brand in the UK. The case remains inconclusive despite multiple trials. The challenge lies in the fact that the defendant's conduct does not satisfy the elements of trademark infringement, yet there is a possibility of exploiting the plaintiff's trademark reputation.

There are a large number of commercial research studies and pieces of literature to prove the effectiveness of this marketing and advertising method, and it is also the financial backbone of various search engine companies. At the same time, a large number of legal documents focusing on the analysis of the "keyword advertisement" problem also discussed the complexity of the problem, and it is difficult to make a unified determination because the use of some trademarks in this situation will not cause confusion or other problems, but some will have serious consequences. Therefore, this article analyzes the negative impact of keyword advertising on the brand value of trademark holders and discusses effective trademark management measures. The negative impact will be analyzed from the two aspects of enterprise marketing effect and brand reputation to guide the factors that enterprises should pay attention to in the marketing process.

2. Related Work

Trademarks can perform their core function of differentiating goods and services in the marketplace, a function that enhances the interests of traders and consumers. At the same time, the scope of exclusivity afforded by trademarks, in turn, allows them to invest in improving the quality of their goods and build a good reputation for their trademarks without fear that third parties will take advantage of their efforts and enable consumers to identify the products sold in the market [3]. The Trademark Act 1994 provides a detailed concept of trademark infringement and several types of situations that may occur [4]. According to Section 10(1)-(3) of the Trade Marks Act 1994, trademark infringement may occur including: goods or goods and services are identical [4]. Trademarks are identical, goods or services are similar and there is a likelihood of confusion. Trademarks are similar, goods or services similar and likely to be confusing. The trade marks are identical or similar, the registered trade mark has a reputation in the UK and use of the defendant's trade mark would unfairly take advantage of or prejudice the distinctive character or reputation of the registered trade mark. In addition, there is a special situation for well-known trademarks, which is called trademark dilution. Establishing trademark infringement requires a determination of whether it is used in a manner affecting others in the course of trade within the UK [5]. It can be seen that the determination of trademark infringement needs to be investigated and determined from various aspects, and only part of the requirements for infringement determination are met. Even if there is a negative impact on the trademark and the trademark holder, it cannot be determined as a trademark infringement rashly.

At present, existing literature points out that placing sponsored advertising terms or related websites at the top of the result list through paid keyword search has the highest conversion rate and users generally tend to click on the terms at the top of the page [6]. Moreover, existing studies have focused on the growing relationship between the economics and law of trademarks. Trademark search is usually the first step for consumers to do brand research. Therefore, advertising has become an internal factor of trademarks, which means that companies will invest a lot of money in building trademarks and their popularity to increase corporate profits [7]. In addition, research on intellectual property rights also discusses the legal dispute whether keyword advertisements are judged as trademark infringement, whose difficulty mainly lies in whether the use of the trademark can be considered reasonable [8].

The impact of keyword advertising on corporate marketing, the relationship between trademark economy and law and the complexity of determining paid keyword search advertising have all been explored and discussed. However, the negative impact of such trademark use on brand value and the possible implementation of corporate trademark management measures have not yet been clarified.

3. Analysis

3.1. Trademark and brand

Trademarks and brands are in a symbiotic relationship. The planning of trademark registration is the logical starting point of brand strategy, the use of trademarks is the basic path of brand strategy, and the protection of trademark rights is the fundamental guarantee of brand strategy [9]. For the consumers, Colin Bates of Building Brands, a UK brand consultancy pointed that brand is a collection of consumers’ perception in their mind, which is intangible [10]. Advertisers pay a search engine company to take another company's traffic (or brand awareness). The parties to the transaction are advertisers and search engine companies and this behavior may damage the relevant rights and interests of trademark holders by using the trademark.

3.2. Google Inc. V Louis Vuitton Malletier

One of the most typical and extreme case is Google Inc. v Louis Vuitton Malletier(LVM) that Google allows some LV imitation websites to be searched for keywords such as "Louis Vuitton Malletier/LVM" so LVM claimed Google infringed its trademark [11]. The case went through several levels of court decisions and finally found that LVM has the right to prohibit unauthorized advertisers from using the same or similar trademarks to place advertisements on Google. However, Google, as a search engine company providing reference services, does not in itself infringe. Meanwhile, this case shows that the subject of responsibility for trademark infringement should be the advertiser. According to the trial process, whether the way of using the trademark affects the essential function of the trademark to identify the source of goods is the key. Notably, the way of use in the above case will inevitably have an adverse impact on the trademark and the company’s trademark management strategy.

3.3. Potential negative impacts

This traffic stealing can cause potential consumers to switch to counterfeit products, resulting in lower sales for the brand. What is more serious is that the target customers of luxury goods pay more attention to the reputation of the brand and its social attributes. Flooding of counterfeits can cause the brand to lose its social identity and reduce its reputation [12]. Moreover, brand image and reputation have a significant impact on consumers' purchasing decisions and company performance and building a good brand image requires a lot of money [13]. In the case of damaged brand reputation, companies need to spend a lot of time and economic costs to repair [14]. However, given that the search engine website will mark the advertiser's entry with the word "sponsored", the identification function of the trademark will not be damaged. If the advertiser is not marketing its own products, it is difficult to be judged as trademark infringement by using the trademark. Therefore, traditional trademark law is more difficult to protect trademark brand reputation from this level.

Nonetheless, there is another similar situation where the trademark holder can pursue a reasonable action through trademark infringement. When an advertiser directly applies a trademark to its trade, this action may constitute infringement. As the case Cosmetic Warriors Limited, Lush Limited v Amazon.co.uk Limited, Amazon Eu Sarl, Lush did not authorize Amazon to sell its products, and Amazon paid for the title of "Lush Soap at Amazon.co.uk" to appear when users searched for "lush", providing "Lush Soap at a low price" and "Amazon orders free in the UK". deliver goods" [15]. On the one hand, Amazon directly used the Lush trademark in the trade process; on the other hand, the website did not make any statement that it was not authorized. Therefore, it is reasonable to believe that consumers will think that the purchase channel is reliable, which involves damage to the identification function of the trademark.

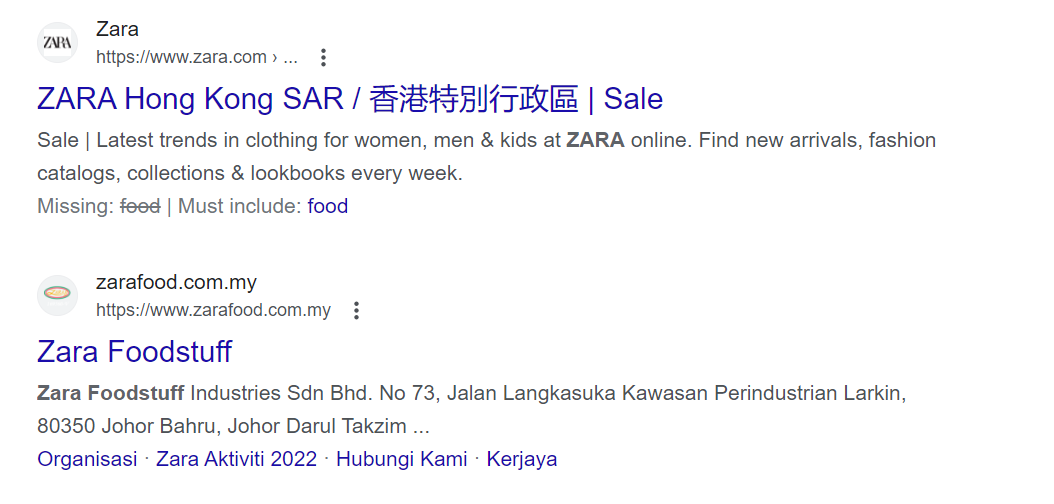

In addition, multiple advertiser entries that appear in the search for brand keywords may reduce the corresponding relationship of some well-known trademarks, resulting in trademark dilution. As Bajpaipointed that trademark dilution involves the unauthorized use of another 's trademark on products that do not compete with and are not disproportionately related to, the trademark owner's products [16]. When a user searches for keywords related to a trademark or brand and the advertiser's entry is displayed in the result, consumers may misunderstand the corresponding relationship, thereby causing economic losses to the trademark holder or the company. As the case ZARA Fashion v ZARA Food, the business fields of the two companies are so different that consumers are unlikely to be confused, but Zara Foods' promotion of the keyword as "zara" can easily lead consumers to mistakenly think that the two belong to the same brand [17]. As shown in the figure 1 below, the entries that appear in the search keyword "zara" are indeed difficult for users to distinguish.

Figure 1: Search results page of “ZARA” (Screenshot by the author)

It is true that keyword advertising has many adverse effects on trademark holders and related companies, and at the same time, it may damage the function of trademarks. However, for consumers, especially those who do not fully understand the products they need or do not understand the market conditions, multiple different search results may help them make choices that are more suitable for their needs. This is also one of the reasons why in some cases, when a trademark is not used in the trade process but only associated with search results (the keyword advertisement), it is considered a normal market competition [18].

4. Discussion

Trademarks and the relevant rights are important both from the perspective of corporate rights and marketing. In view of the fact that whether a keyword advertisement is infringing depends on its specific usage, but adverse effects always exist in complex situations, enterprises should consider proactively reducing the possibility of trademark brand damage in terms of trademark design, use and management. Based on the registered corporate trademark, there are the following two preventive or mitigation measures that can be referred to.

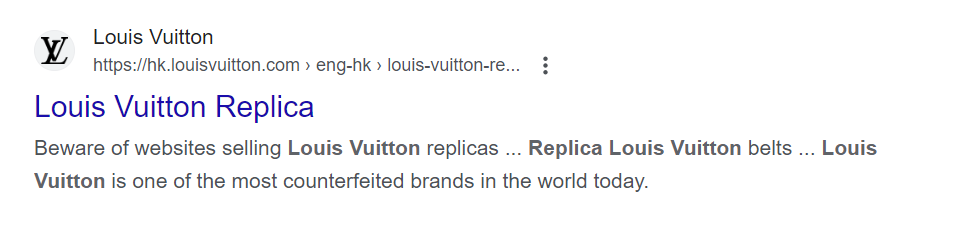

Firstly, issue a statement in the form of an official entry to deal with counterfeit advertisements or informal and unauthorized channel advertisements in keyword results. This method is the most direct solution to consumer confusion and can deal with situations that do not constitute infringement but affect the reputation of the trademark. Louis Vuitton who has long been affected by counterfeits adopted this method. As shown in the figure 2 below through Google's search results, the official statement on preventing counterfeit and inferior products appears at the top of the results page.

Figure 2: Louis Vuitton's official statement on fake websites

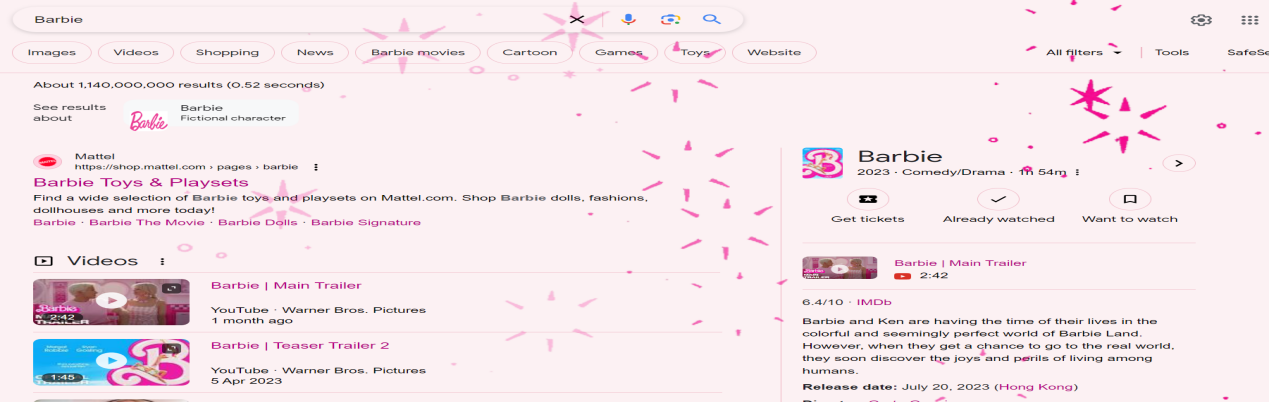

Secondly, specializing the keyword result page through payment is a vivid way to effectively enhance the corresponding relationship between trademark keywords and trademark brands. The effect of this method is particularly prominent for animation animation or products with aesthetic attributes. As the well-known animation IP Barbie, when users search for the keyword "Barbie" on Google, its representative Barbie pink animation effect will appear on the result page. This is also a measure to directly face consumers and users, but there are certain requirements for the characteristics of trademarks or products, and not all trademarks can achieve the desired effect in a similar way.

Figure 3: Enhanced elements display page for the "Barbie" keyword search

5. Conclusion

The Internet era has given birth to various new marketing models, which pose huge challenges to the trademark law that was born on the market economy. The negative impact analysis and measures in this article are mostly from the perspective of commercial marketing, but not from the perspective of legislation. In addition, the cited cases pay more attention to the cases of well-known trademarks, but do not involve the keyword infringement of ordinary trademarks. The trademark infringement issue involved in keyword search advertising discussed in the above analysis is only one of many challenges. For this complex situation, trademark law should be combined with market digital marketing research to fully understand the online market, consumer behavior and many influences to revise and issue reasonable judicial documents to guide the judgment of similar cases, maintain free and fair competition in the market, and protect trademarks rights of holders and consumers.

References

[1]. Chalil, M. T., Dahana, W. D. and Baumann, C. (2020) ‘How do search ads induce and accelerate conversion? The moderating role of transaction experience and organizational type’, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 116, pp. 324-336.

[2]. Interflora Inc. v Marks & Spencer Plc. [2014] EWHC 4168

[3]. [3] Fernandez-Mora, A. (2021) ‘Trade Mark Functions in Business Practice: Mapping the Law Through the Search for Economic Content’, International Review of Intellectual Property and Competition Law, Vol. 52, pp. 1370-1404. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40319-021-01113-2 (Accessed: 16 July 2023).

[4]. The Trademark Act 1994

[5]. Bently, L. et al. (2022) Intellectual Property Law, 6th edition. Oxford: Oxford University. Available at: https://doi-org.oxfordbrookes.idm.oclc.org/10.1093/he/9780198869917.001.0001 (Accessed: 15 July 2023).

[6]. Agarwal, H., Birajdar, A., & Bolia, M. (2019) ‘Search Engine Marketing Using Search Engine Optimisation’, Asian Journal For Convergence In Technology (AJCT), Vol.6 (1). Available at: https://asianssr.org/index.php/ajct/article/view/737 (Accessed: 15 July 2023).

[7]. Patra, S.P. and Singh, P. (2021) ‘ Journey of Trademarks from Conventional to Un-Conventional - A Legal Perspective’, Journal of Intellectual Property Rights, Vol. 26(3), pp. 162-170. Available at: http://op.niscpr.res.in/index.php/JIPR/article/view/44167 (Accessed: 15 July 2023).

[8]. Burrell, R. and Handler, M. (2020) ‘Keyword Advertising and Action Consumer Confusion’, Research Handbook on Intellectual Property and Digital Technologies, Chapter 21. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3776895 (Accessed: 15 July 2023).

[9]. Jia, L. (2019) ‘The symbiosis and future of trademarks and brands’, Chinese Trademark, 261(05), pp.70-72. Available at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=Wz7QSVtT7FaqEVwLh4-ZRnikOg7e-EVo5j8vw8QIv1jwPC4zJ6oU8Uk2P3iZNL_0-_3f0tZ2Kwau7gLx-qB7sjpi-2J_RbBKhPZWR90T-mYDjxctsOJ1F0GEIGsgMKNvk5suaqJNpSg=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (Accessed: 15 July 2023).

[10]. Murray, A. (2019) Information Technology Law: The law and society, 4 edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Accessed: 15 July 2023).

[11]. Louis Vuitton v Google France [2011] All E.R.(EC) 411

[12]. Wirtz, J., Holmqvist, J. and Fritze M. P. (2020) ‘Luxury services’, Journal of Service Management, Vol. 31(4).

[13]. Mu, J.F. and Zhang, J.Z. (2021) ‘Seller marketing capability, brand reputation, and consumer journeys on e-commerce platforms’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 49. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-021-00773-3 (Accessed: 16 July 2023).

[14]. Krasnikov, A. and layachandran, S. (2022) ‘Building Brand Assets: The Role of Trademark Rights’, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 59(5).

[15]. Cosmetic Warriors Limited, Lush Limited v Amazon.co.uk Limited, Amazon Eu Sarl [2014] EWHC 181

[16]. Bajpai, A. (2019) ‘Keywords and Infringement of Trademark in Cyberspace’, Nation Journal of Cyber Security Law, Vol. 2(1).

[17]. Khaitan &Co. (2015) ‘The owner of the ZARA clothing store has banned restaurants from using ZARA TAPAS BAR’, World Trademark Review. Available at: https://www.worldtrademarkreview.com/article/owner-of-zara-clothing-prevents-use-of-zara-tapas-bar-restaurants (Accessed: 18 July 2023).

[18]. Ghose, A. and Yang, S. (2009) ‘An Empirical Analysis of Search Engine Advertising: Sponsored Search in Electronic Markets’, Management Science, Vol. 55(10).

Cite this article

Miao,R. (2024). Research on the Potential Trademark Infringement Issues and Negative Effects of Keyword Search Advertisements under the Internet Economy. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,66,212-217.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Business and Policy Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Chalil, M. T., Dahana, W. D. and Baumann, C. (2020) ‘How do search ads induce and accelerate conversion? The moderating role of transaction experience and organizational type’, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 116, pp. 324-336.

[2]. Interflora Inc. v Marks & Spencer Plc. [2014] EWHC 4168

[3]. [3] Fernandez-Mora, A. (2021) ‘Trade Mark Functions in Business Practice: Mapping the Law Through the Search for Economic Content’, International Review of Intellectual Property and Competition Law, Vol. 52, pp. 1370-1404. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40319-021-01113-2 (Accessed: 16 July 2023).

[4]. The Trademark Act 1994

[5]. Bently, L. et al. (2022) Intellectual Property Law, 6th edition. Oxford: Oxford University. Available at: https://doi-org.oxfordbrookes.idm.oclc.org/10.1093/he/9780198869917.001.0001 (Accessed: 15 July 2023).

[6]. Agarwal, H., Birajdar, A., & Bolia, M. (2019) ‘Search Engine Marketing Using Search Engine Optimisation’, Asian Journal For Convergence In Technology (AJCT), Vol.6 (1). Available at: https://asianssr.org/index.php/ajct/article/view/737 (Accessed: 15 July 2023).

[7]. Patra, S.P. and Singh, P. (2021) ‘ Journey of Trademarks from Conventional to Un-Conventional - A Legal Perspective’, Journal of Intellectual Property Rights, Vol. 26(3), pp. 162-170. Available at: http://op.niscpr.res.in/index.php/JIPR/article/view/44167 (Accessed: 15 July 2023).

[8]. Burrell, R. and Handler, M. (2020) ‘Keyword Advertising and Action Consumer Confusion’, Research Handbook on Intellectual Property and Digital Technologies, Chapter 21. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3776895 (Accessed: 15 July 2023).

[9]. Jia, L. (2019) ‘The symbiosis and future of trademarks and brands’, Chinese Trademark, 261(05), pp.70-72. Available at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=Wz7QSVtT7FaqEVwLh4-ZRnikOg7e-EVo5j8vw8QIv1jwPC4zJ6oU8Uk2P3iZNL_0-_3f0tZ2Kwau7gLx-qB7sjpi-2J_RbBKhPZWR90T-mYDjxctsOJ1F0GEIGsgMKNvk5suaqJNpSg=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (Accessed: 15 July 2023).

[10]. Murray, A. (2019) Information Technology Law: The law and society, 4 edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Accessed: 15 July 2023).

[11]. Louis Vuitton v Google France [2011] All E.R.(EC) 411

[12]. Wirtz, J., Holmqvist, J. and Fritze M. P. (2020) ‘Luxury services’, Journal of Service Management, Vol. 31(4).

[13]. Mu, J.F. and Zhang, J.Z. (2021) ‘Seller marketing capability, brand reputation, and consumer journeys on e-commerce platforms’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 49. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-021-00773-3 (Accessed: 16 July 2023).

[14]. Krasnikov, A. and layachandran, S. (2022) ‘Building Brand Assets: The Role of Trademark Rights’, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 59(5).

[15]. Cosmetic Warriors Limited, Lush Limited v Amazon.co.uk Limited, Amazon Eu Sarl [2014] EWHC 181

[16]. Bajpai, A. (2019) ‘Keywords and Infringement of Trademark in Cyberspace’, Nation Journal of Cyber Security Law, Vol. 2(1).

[17]. Khaitan &Co. (2015) ‘The owner of the ZARA clothing store has banned restaurants from using ZARA TAPAS BAR’, World Trademark Review. Available at: https://www.worldtrademarkreview.com/article/owner-of-zara-clothing-prevents-use-of-zara-tapas-bar-restaurants (Accessed: 18 July 2023).

[18]. Ghose, A. and Yang, S. (2009) ‘An Empirical Analysis of Search Engine Advertising: Sponsored Search in Electronic Markets’, Management Science, Vol. 55(10).