1. Introduction

In today's progressively varied educational setting, classrooms contain students from different languages and cultural histories, creating a vibrant multilingual environment. In these situations, it comes to be essential to recognize complicated language practices, such as code mixing.

Code-mixing involves the seamless integration of language elements from two or more languages in a single dialogue or sentence, which is now a key aspect of how bilingual and multilingual individuals communicate [1]. This code-mixing practice is especially prevalent among multilingual individuals, notably in bilingual settings such as Shanghai International School. Although it has historically been considered as a sign of language deficiency, recent research studies have actually redefined code-mixing as a complicated approach that can improve the communication and cognitive process [2].

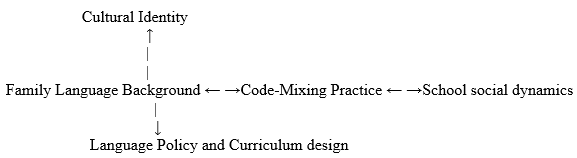

This research study utilizes a qualitative conceptual framework to examine the code-mixing phenomenon and placement it as the core of the evaluation. The structure stresses the connection in between a number of vital factors - language policy and curriculum design, social environment, family language background and cultural identity - which contribute to the code-mixing practices of bilingual pupils. With this study, the study aims to give valuable insights for educators and decision-makers, support the enhancement of bilingual education, and promote far better learning outcomes and cultural integration of students in various educational atmospheres.

Figure 1: Qualitative conceptual framework

Code-mixed practices are deeply rooted in an intricate network of variables, and cultural identity and school social dynamics play a crucial duty. These aspects straight influence the code-mixing through social interaction and personal expression of personal identity. Although language policies and curriculum content do not directly influence code-mixing, they contribute to creating an educational structure that encourages the emergence of this behavior. While family language background is not the main influence for local students, it offers a reference point and indirectly underscores the significance of the school environment in shaping language preferences.

2. Background

Code mixing, that is, the blending of aspects of two languages in discussion, is a crucial linguistic sensation, particularly among bilingual pupils [3]. In the past, this behavior was typically regarded as an indicator of language defects. Nonetheless, modern study has actually redefined it as a complex and very intricate language technique rooted in sociolinguistics, which is especially common in multilingual environments [4]. In a bilingual educational environment, children frequently use code-mixing to meet the challenge of balancing both languages in the academic and social context.

A number of crucial aspects have actually caused the incident of bilingual pupils's code mixing. School language policy and curriculum design are the primary influencing elements. Social interaction, consisting of peer dynamics within the school and the wider social environment, additionally plays an essential duty in shaping the mix of pupils' use code. Furthermore, the interaction between the household language environment and the institution setting better affects the code-mixing tendency of kids.

Cultural identity is an additional vital element, due to the fact that trainees try to stabilize the protection of their cultural heritage while adjusting to the multilingual environment, which impacts their use code-mixing [5][6]. A much deeper understanding of these elements is crucial for creating instructional practices and policies to much better support bilingual pupils, improve their knowledge experience and cultural integration.

Although numerous kinds of code mixing, such as insertion and intra-verbal mixing, have been extensively researched in the research of multilingual children, this research study mainly concentrates on identifying the vital aspects that drive the code-mixing behavior of bilingual pupils. Although etymological research offers important insights right into the complexity of code mixing, this research study stresses the social, cultural and instructional pressures behind these practices and gives a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomena in a bilingual setting.

3. Objectives and scope of the study

This term paper deeply explores the reasons behind the code-mixing of multilingual and multilingual trainees, and studies the aspects that form this language behavior in the educational environment where English is utilized as the language. The study’s key objectives are:

Analyze the main factors driving code-mixing, such as language policies, curriculum content, social influences, family language practices, and cultural identity.

Investigate how school language policies and curriculum structures affect students' use of code-mixing, particularly in environments that foster bilingual or multilingual communication.

Explore the role of peer interactions and the broader social setting in schools, and how they encourage code-mixing as a means of social connection and communication.

Assess how the language environment at home complements or counteracts the school setting in promoting or limiting code-mixing behaviors.

Examine how cultural identity influences students' use of code-mixing, particularly in balancing cultural authenticity with adapting to multilingual contexts. The study specifically focuses on bilingual classrooms where English is the language being learned. The literature review will summarize key findings from previous research, highlight major themes, trends, and gaps in the literature, and offer insights for future research and educational practice.

4. Significance of the study

This study deeply studies the variables that advertise the code-mixing of bilingual trainees, paying unique interest to the educational setting with English as the target language. These findings supply useful understandings that can form teaching strategies and expand the understanding of bilingual behavior. These insights are especially pertinent to educators, decision-makers and researchers, due to the fact that they can influence the growth of language education programs, teacher training programs and curriculum design. Additionally, the research enriches the ongoing conversation on the effect of cultural identity and family language background on language acquisition, and motivates much more inclusive and situation-sensitive strategies to bilingual education. Ultimately, the research study intends to enhance the educational method of multilingual pupils and boost their language learning outcomes by growing their understanding of the complex dynamics of code mixing.

Importance for educators, decision-makers and linguists.

Insights on boosting language education strategies, teacher development and curriculum design.

Assessment of cultural identity and family language background in language acquisition.

The potential of boosting the language learning outcomes of bilingual trainees.

5. Literature review

5.1. Code-Mixing: definitions and types

Code-mixing describes the practice of blending words from one language into the grammatical framework of another language in a dialogue. This method commonly appears in bilingual and multilingual class, and it is a reliable interaction tool for people discovering brand-new languages [1].

According to Muysken's [7] classification, scholars categorize code-mixing into various types, each reflecting different linguistic strategies employed by multilingual speakers. For instance, Insertional Mixing refers to the embedding of a phrase or a marker from one language into the syntactic structure of a dominant language, allowing for subtle language blending. In contrast, Congruent Lexicalization occurs when elements from multiple languages are interwoven within the same utterance, facilitating the seamless integration of linguistic features. Alternational Mixing involves switching at the boundaries of syntactic units in different languages, often encompassing larger language fragments. Furthermore, when the grammatical structures of two languages are similar, Congruent Lexicalization enables the fluid amalgamation of lexical elements from both languages [7].

These classifications give an in-depth understanding of exactly how bilingual individuals browse and blend languages in communication, paying unique attention to the inner blending of language in sentence and discourse frameworks, which is the essence of code mixing.

The existing research mostly focuses on the linguistic qualities of code mixing, but this research study deeply researches the key aspects that shape the code-mixing behavior of bilingual pupils, paying unique focus to the impact of education and learning and socio-cultural influences. This sight enriches our understanding of code-mixing and highlights its relevance in bilingual education. The following chapters will review vital aspects, such as code-mixing in bilingual courses, language policy, social environment, family language background and cultural identity, every one of which plays an important role in affecting the pattern of code mixing.

5.2. Code-Mixing in bilingual classrooms

The study also shows that there is a positive link between English proficiency and attitude towards code switching, which shows that trainees are extra likely to mix languages in a setting where they really feel comfortable and proficient. This reinforces the idea that the school environment plays a pivotal role in shaping language use among bilingual students.

In discussing code-mixing in international schools in Shanghai, Tan [8] underscored the need to understand the cultural backdrop of educational policymaking to fully grasp the flexibility of language policies and curriculum content. As Tan pointed out, "Shanghai's educational reforms demonstrate responsiveness to the needs of international students and support the internationalization of education through flexible language policies" [8].

Based on Tan’s insights, this demonstrates how flexible language policies in schools enable students to fluidly switch between languages, creating an environment that encourages code-mixing. This is seen as a direct result of policies that prioritize linguistic flexibility over rigid language rules. Furthermore, Lam [9] clarified the regional differences in the execution of multilingual and multilingual education and learning plans in numerous parts of China, and pointed out that international schools apply these policies a lot more easily. This adaptability substantially impacts pupils' language choices and encourages code mixing, suggesting that Tan's adaptive concept is successfully utilized to meet pupils' various language needs in these environments.

However, Gao and Ren stressed the dispute surrounding China's bilingual education policy [10]. These discussions not just impact the language development of pupils, however also have a considerable effect on their cultural identity, more complicating the dynamics of code mixing. By researching these numerous elements, we have a more comprehensive understanding of the factors that promote the code-mixed practices of Shanghai International School.

The social dynamics within the college have significantly influenced students' use of code-mixing, with peer interactions playing a key role in shaping language practices. Studies indicate that students often engage in code-mixing to fit into social groups or adjust to different institutional settings[11].

At Shanghai International School, where social and linguistic diversity is widespread, code-mixing has become a way for students to assert their identity and foster a sense of belonging. Moreover, peer pressure strongly affects code-mixing in multilingual groups, helping sustain social bonds[12].

However, some groups that value linguistic purity may perceive code-mixing negatively, highlighting that views on this practice vary based on social and cultural contexts[13].

From the perspective of students, there are a number of variables that urge the use of code-mixing in multilingual classes. Some students locate that incorporating the first language with English, it improves their capability to discover and connect effectively, assists in clarifying complex ideas, and enables clearer expression. Additionally, matching English with the mother tongue assists trainees in connecting the two languages, construct their confidence, and motivate them to actively take part in classroom tasks [14]. Those that value the benefits of code-mixing are more probable to use it to grow an inclusive learning environment where their language development is supported [15]. Consequently, code-mixing is a sensible device to enhance pupils' engagement, self-confidence and learning outcomes.

From the viewpoint of instructors, code-mixing is considered a vital way to bridge the gap between students' first language and target language. Teachers can make use of elements of students' mother tongue to streamline complex concepts and boost understanding, so regarding produce a more effective learning experience [16]. This technique not just enhances understanding, yet additionally enhances students' self-confidence, to ensure that they can participate a lot more in classroom discussions. In addition, educators can teach pupils how to efficiently switch over in between languages, enhance metallic language awareness and assistance language acquisition. Finally, from the perspective of teachers, code-mixing enriches the dynamics of the class and produces an extra inclusive learning atmosphere.

Code-mixing additionally advertises understanding by aiding students discuss definition and decrease misunderstandings when fighting with complex ideas in the target language [17]. Teachers frequently use code-mixing to examine understanding, give feedback, and encourage active participation, which aids students internalize the material [18]. Additionally, by using code-mixing to create an inclusive learning environment, pupils' confidence is boosted so that they can take part more totally in the conversation [19]. By incorporating several languages, students also cultivate a better awareness of metallic language, allowing them to share complex ideas better and boost their general understanding. These variables highlight how code-mixing can become a beneficial device to promote understanding and enhance finding out end results in multilingual classrooms.

5.3. Family language background

For local students attending Shanghai International School, the language spoken at home is typically Chinese, as many parents in China do not speak English. Although these students primarily speak Chinese at home due to the limited English proficiency of their parents, the school environment exerts significant influence on their language use. Specifically, the necessity to adapt to an English-dominated educational setting and engage in peer interactions in English prompts frequent mixing of English into their daily communication [20].

The theory of cross-language highlights that bilingual individuals utilize elements from their full language repertoire during communication. For bilingual children, this means the language practices they establish at home strongly affect their inclination to mix codes. Consequently, when these students experience a mix of Chinese at home and English at school, they tend to combine both languages as a communication strategy, merging aspects of both linguistic environments [21].

5.4. Cultural identity

Cultural identity plays a crucial role in shaping code-mixed practices, as evidenced by research study in different socio-language environments. As an example, Arab-American poets make use of code-mixing as a powerful device to harness their dual identity, integrating various cultural elements to share their layered experiences. A study by Zina, Tariq, Ahmed, Arwa, Hussein and Mohammed completely examined this dynamic. They analyzed the way Arab-American poets make use of language strategies to show their dual-cultural narratives. Likewise, in Malaysia, public figures like Yuna use code-mixing as a way to enhance regional identification and establish contacts in the multicultural context discovered this topic by analyzing Yuna's public participation [21].

6. Discussion

In China, the relationship between cultural identity and language is also extremely essential. Zixi Jiang has actually deeply examined how Chinese learners integrate code-mixing right into their second language learning process, and demonstrated the dynamic interaction in between cultural identity and language selection in China's rapidly transforming multilingual environment. Nonetheless, an alternative view proposes that students may sometimes deliberately refrain from code-mixing to maintain the "purity" of their cultural identity. This shows that the role of cultural identity in code-mixing can differ widely based on personal circumstances and wider societal expectations.

As evidenced by existing literary works, the school's language policy and curriculum content play an essential role in shaping trainees' code-mixed behavior. Nonetheless, lots of studies often tend to concentrate on the more comprehensive connection between these policies and general trainee behavior, often neglecting specific nuances in student experiences. Future study must position more focus on understanding just how students perceive and implement these language strategies in the discovering procedure. Although bilingual policies and bilingual courses produce possibilities for code-mixing, it is needed to discover whether they unintentionally increase anxiety or confusion, and just how they efficiently advertise academic success. For instance, because of social or academic pressure, some trainees may stay clear of using their mother tongue, which might have an unfavorable influence on their participation and learning experience [22]. Although code-mixing has been proven to help comprehend complex ideas, trainees might still stay clear of utilizing code for fear of objection [23].

The social environment inside the institution has additionally had a considerable influence on the code mixing, with positive and adverse effects. On the one hand, peer interaction and social pressure can aid pupils develop social connections and cultivate a sense of belonging with code-mixing. On the other hand, if some colleagues have a negative view of code mixing, students may really feel separated or pressured to reduce their natural language practices. This double influence highlights the relevance of multilingual education policies to promote an inclusive social environment, ensuring that trainees from various language backgrounds can fully take part without bothering with being marginalized because of making use of their mother tongue.

Although it might seem straightforward, the impact of family language background on code-mixing behavior is in fact quite complicated. Although many students mostly utilize their mother tongue in the house, they commonly switch over to a second language at institution, resulting in inconsistent language use, which may influence their emotional and mental health. As an example, when pupils can't utilize their mother tongue freely at school, they might feel distressed or discover it difficult to practice the school language in the house [24]. Consequently, more study is required to explore the communication between the home and school language environments and exactly how it impacts the total language development.

Cultural identity likewise plays a crucial function fit code-mixed behavior. In a multicultural environment, code-mixing is generally a means for pupils to share and attest their cultural identity, showing their link with multiple cultures. Nonetheless, some students might stay clear of code-mixing in order to preserve the regarded "pureness" of their cultural identity, which is affected by family upbringing, social expectations or personal beliefs. As a result, future research studies should deeply study just how cultural identity connects with language usage in various language environments, and just how students can strike an equilibrium between expressing identification and adapting to a multilingual environment. Educators ought to also assist pupils understand and accept the intricacy of multicultural identity in a multicultural educational environment.

7. Conclusion

The code-mixing of bilingual youngsters in Shanghai International School is formed by a collection of variables, consisting of language policy, curriculum design, social dynamic, family language background and cultural identity. The analysis highlights the intricate communication between these elements and offers insights right into the device of code-mixing in the academic context. A much deeper understanding of these developments can offer info for the development of even more reliable language plans and training techniques to far better assist multilingual and cultural diversity.

It is very important to emphasize that this research study is based on a comprehensive testimonial of existing literary works, omitting empirical research studies in Shanghai schools. For that reason, the final thoughts attracted reflect wider patterns, however might not be able to record the details intricacy of the personal educational environment. In order to enhance this search for and discover the neighborhood effect of these aspects, future research studies ought to concentrate on thorough field research in Shanghai International School. Such a study will certainly not only check the general applicability of these conclusions, however likewise reveal school-specific dynamics, which might cause much more customized educational methods.

References

[1]. Sitaram, S., & Black, A. W. (2016). Speech synthesis of code-mixed text. Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC'16), 3422–3428. European Language Resources Association (ELRA), Portorož, Slovenia.

[2]. Kumari, S. (2024). Code-mixing and code-switching in multilingual classrooms: Enhancing second language acquisition of English. Chetana: International Journal of Education, 9(2), 9-16. https://www.echetana.com/Vol.-09,-No.-02,-April-June-2024

[3]. Poplack, S., & Walker, J. A. (2003). Pieter Muysken, Bilingual speech: A typology of code-mixing (book review). Journal of Linguistics, 39(3), 678-683. DOI: 10.1017/S0022226703272297

[4]. Ezeh, N. G., Umeh, I. A., & Anyanwu, E. C. (2022). Code Switching and Code Mixing in Teaching and Learning of English as a second language: Building on knowledge. English Language Teaching, 15(9), 106-113.

[5]. Grosjean, F. (1982). Life with two languages: An introduction to bilingualism. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

[6]. Blackledge, A., & Pavlenko, A. (2001). Negotiation of identities in multilingual contexts. Journal of Language and Politics, 5(3), 243-257. https://doi.org/10.1177/13670069010050030101

[7]. Moyer, M. G. (2002). Review: Bilingual Speech: A Typology of Code-Mixing by Pieter Muysken. Language in Society, 31(4), 621-624. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4169206

[8]. Tan, C. (2012). The culture of education policy making: Curriculum reform in Shanghai. Critical Studies in Education, 53(2), 153-167

[9]. Lam, A. S. L. (2007). Bilingual or multilingual education in China: Policy and learner experience. Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 64, 13.

[10]. Gao, X., & Ren, W. (2019). Controversies of bilingual education in China. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 22(3), 267-273.

[11]. Salah, R. (2023). Arabic-English mixing among English-language students at Al al-Bayt University: A sociolinguistic study. International Journal of Arabic-English Studies, 23(2), 319-338. doi:10.33806/ijaes.v23i2.466

[12]. Wartinah, N. N., & Wattimury, C. N. (2018). Code switching and code mixing in English language studies' speech community: A sociolinguistics approach. Berumpun: International Journal of Social, Politics, and Humanities, 1(1), 8-14. Retrieved from https://mail.berumpun.ubb.ac.id/index.php/BRP/article/view/2/2

[13]. Sewell, A. (2024). The discourse of ‘falling standards’ of English in Hong Kong. World Englishes. https://doi.org/10.1111/weng.12656

[14]. Islam, M. M. (2023). The especial causes of weakness behind learning English language in the secondary schools: A case study of Rangpur district. British Journal of Arts and Humanities, 5(4), 209-227. https://www.semanticscholar.org/reader/fa869ce5205cc2d7fd523094ace7feb3e7728a12

[15]. Lin, S. W. (2020). Analysis of Taiwan’s English curriculum and teaching materials from the perspective of English as a lingua franca. Research Square. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342972902_Analysis_of_Taiwan's_English_Curriculum_and_Teaching_Materials_from_the_Perspective_of_English_as_a_Lingua_Franca/fulltext/5f0fbf0ca6fdcc3ed70b5509/Analysis-of-Taiwans-English-Curriculum-and-Teaching-Materials-from-the-Perspective-of-English-as-a-Lingua-Franca.pdf

[16]. Jiang, Y. L. B., García, G. E., & Willis, A. I. (2014). Code-mixing as a bilingual instructional strategy. Bilingual Research Journal, 37(3), 311-326.

[17]. Maillat, D., & Serra, C. (2009). Immersion education and cognitive strategies: Can the obstacle be the advantage in a multilingual society? International Journal of Multilingualism, 6(2), 186-206.

[18]. Astrachan, O. L., Duvall, R. C., Forbes, J., & Rodger, S. H. (2002, November). Active learning in small to large courses. In 32nd Annual Frontiers in Education (Vol. 1, pp. T2A-T2A). IEEE.

[19]. Tai, K. W. (2022). Translanguaging as inclusive pedagogical practices in English-medium instruction science and mathematics classrooms for linguistically and culturally diverse students. Research in Science Education, 52(3), 975-1012.

[20]. Guo, Y. (2023). The code-mixing of Chinese and English among Chinese college students: A qualitative study. In Proceedings of the 2022 4th International Conference on Literature, Art and Human Development (ICLAHD 2022) (pp. 73-89). https://doi.org/10.2991/978-2-494069-97-8_11

[21]. Azahari, N. K., & Mohamad, N. H. S. (2023). Bridging Identities: Analysing Code-Mixing in Yuna's Conversation with a Local Malaysian Activist. Journal for the Study of English Linguistics, 11(1), 52-69.

[22]. Hornberger, N. H., & Link, H. (2012). Translanguaging in today's classrooms: A biliteracy lens. Theory into practice, 51(4), 239-247.

[23]. Swain, M., & Lapkin, S. (2000). Task-based second language learning: The uses of the first language. Language teaching research, 4(3), 251-274.

[24]. Cummins, J. (2000). Language, power and pedagogy: Bilingual pupils in the crossfire. Multilingual Matters.

Cite this article

Qiao,M. (2025). Literature Review: Main Factors Contributing to Code-Mixing among Bilingual Pupils in Shanghai's International Schools. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,92,118-125.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Sitaram, S., & Black, A. W. (2016). Speech synthesis of code-mixed text. Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC'16), 3422–3428. European Language Resources Association (ELRA), Portorož, Slovenia.

[2]. Kumari, S. (2024). Code-mixing and code-switching in multilingual classrooms: Enhancing second language acquisition of English. Chetana: International Journal of Education, 9(2), 9-16. https://www.echetana.com/Vol.-09,-No.-02,-April-June-2024

[3]. Poplack, S., & Walker, J. A. (2003). Pieter Muysken, Bilingual speech: A typology of code-mixing (book review). Journal of Linguistics, 39(3), 678-683. DOI: 10.1017/S0022226703272297

[4]. Ezeh, N. G., Umeh, I. A., & Anyanwu, E. C. (2022). Code Switching and Code Mixing in Teaching and Learning of English as a second language: Building on knowledge. English Language Teaching, 15(9), 106-113.

[5]. Grosjean, F. (1982). Life with two languages: An introduction to bilingualism. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

[6]. Blackledge, A., & Pavlenko, A. (2001). Negotiation of identities in multilingual contexts. Journal of Language and Politics, 5(3), 243-257. https://doi.org/10.1177/13670069010050030101

[7]. Moyer, M. G. (2002). Review: Bilingual Speech: A Typology of Code-Mixing by Pieter Muysken. Language in Society, 31(4), 621-624. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4169206

[8]. Tan, C. (2012). The culture of education policy making: Curriculum reform in Shanghai. Critical Studies in Education, 53(2), 153-167

[9]. Lam, A. S. L. (2007). Bilingual or multilingual education in China: Policy and learner experience. Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 64, 13.

[10]. Gao, X., & Ren, W. (2019). Controversies of bilingual education in China. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 22(3), 267-273.

[11]. Salah, R. (2023). Arabic-English mixing among English-language students at Al al-Bayt University: A sociolinguistic study. International Journal of Arabic-English Studies, 23(2), 319-338. doi:10.33806/ijaes.v23i2.466

[12]. Wartinah, N. N., & Wattimury, C. N. (2018). Code switching and code mixing in English language studies' speech community: A sociolinguistics approach. Berumpun: International Journal of Social, Politics, and Humanities, 1(1), 8-14. Retrieved from https://mail.berumpun.ubb.ac.id/index.php/BRP/article/view/2/2

[13]. Sewell, A. (2024). The discourse of ‘falling standards’ of English in Hong Kong. World Englishes. https://doi.org/10.1111/weng.12656

[14]. Islam, M. M. (2023). The especial causes of weakness behind learning English language in the secondary schools: A case study of Rangpur district. British Journal of Arts and Humanities, 5(4), 209-227. https://www.semanticscholar.org/reader/fa869ce5205cc2d7fd523094ace7feb3e7728a12

[15]. Lin, S. W. (2020). Analysis of Taiwan’s English curriculum and teaching materials from the perspective of English as a lingua franca. Research Square. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342972902_Analysis_of_Taiwan's_English_Curriculum_and_Teaching_Materials_from_the_Perspective_of_English_as_a_Lingua_Franca/fulltext/5f0fbf0ca6fdcc3ed70b5509/Analysis-of-Taiwans-English-Curriculum-and-Teaching-Materials-from-the-Perspective-of-English-as-a-Lingua-Franca.pdf

[16]. Jiang, Y. L. B., García, G. E., & Willis, A. I. (2014). Code-mixing as a bilingual instructional strategy. Bilingual Research Journal, 37(3), 311-326.

[17]. Maillat, D., & Serra, C. (2009). Immersion education and cognitive strategies: Can the obstacle be the advantage in a multilingual society? International Journal of Multilingualism, 6(2), 186-206.

[18]. Astrachan, O. L., Duvall, R. C., Forbes, J., & Rodger, S. H. (2002, November). Active learning in small to large courses. In 32nd Annual Frontiers in Education (Vol. 1, pp. T2A-T2A). IEEE.

[19]. Tai, K. W. (2022). Translanguaging as inclusive pedagogical practices in English-medium instruction science and mathematics classrooms for linguistically and culturally diverse students. Research in Science Education, 52(3), 975-1012.

[20]. Guo, Y. (2023). The code-mixing of Chinese and English among Chinese college students: A qualitative study. In Proceedings of the 2022 4th International Conference on Literature, Art and Human Development (ICLAHD 2022) (pp. 73-89). https://doi.org/10.2991/978-2-494069-97-8_11

[21]. Azahari, N. K., & Mohamad, N. H. S. (2023). Bridging Identities: Analysing Code-Mixing in Yuna's Conversation with a Local Malaysian Activist. Journal for the Study of English Linguistics, 11(1), 52-69.

[22]. Hornberger, N. H., & Link, H. (2012). Translanguaging in today's classrooms: A biliteracy lens. Theory into practice, 51(4), 239-247.

[23]. Swain, M., & Lapkin, S. (2000). Task-based second language learning: The uses of the first language. Language teaching research, 4(3), 251-274.

[24]. Cummins, J. (2000). Language, power and pedagogy: Bilingual pupils in the crossfire. Multilingual Matters.