1.Introduction

Cambodia has been dubbed the “NGO ghetto” given the abundance of NGOs in the country: 5,062 NGOs are recorded in the CSO Database. From 2017 to 2019, 19% of the total average funds in the NGO sector were directed to education [1]. In a unique position to supplement the public education system, NGOs related to education in Cambodia often target at-risk youth, particularly those who are economically disadvantaged or academically challenged in public schools [2]. To provide support beyond academics to these at-risk youth, educational NGOs in Cambodia include non-academic elements in their curricula, such as life skills, vocational education, and social and emotional learning (SEL) [3]. Promoting non-academic and relationship skills, particularly social and emotional learning, in children and young adults has promising effects on promoting equity and future success [4-7]. In Cambodia, a developing nation, NGOs have promising potential to empower less economically advantaged youth and reduce disparity by promoting SEL competencies. However, correct implementation is pivotal to SEL competency outcomes [5,8]. Forming the third sector, NGOs face limitations with standardization [9-11]. NGOs adopt various educational approaches and objectives in Cambodia, resulting in varying effects on SEL. Therefore, it is worthwhile to compare educational NGOs to identify the strengths and effects of existing programs in promoting SEL. The results could inform improvements to other educational programs in developing countries or target less economically advantaged youth. In this paper, mixed-method design involving surveys, interviews, and observations was applied. Surveys were used to assess the SEL levels in students enrolled in the two NGO educational programs, while interviews distinguished organizational differences. Then, observational notes were used for triangulation and to corroborate evidence on SEL competencies and organizational attributes. Considering one NGO operates a full-time school and the other runs an academic enrichment program, the goals of educational programs in the two schools differ and logically, so would the expected SEL outcomes. The author hypothesizes that there would be some significant distinctions between the SEL levels of the two groups of students enrolled in the two different educational programs offered by the two dissimilar NGOs.

2. Background Information

2.1. Social Issues

In light of the proliferation and increasing standings of NGOs, several studies have called into question the efficacy of NGOs and pointed out weaknesses. Common shortcomings occur with dependency on benefactors, loose connections with local civil society, and inadequate approaches to complex problems [9-11]. According to Rose, the efficacy and benefits of NGO-provided education programs in general still require more systematic investigation to determine [12]. At present, NGOs simply give people an alternative way to think, act, and produce tangible results independent of government means [13]. In Cambodia, a developing nation, educational NGOs are abundant but not standardized. The requisites for Cambodian NGOs to operate in Cambodia before 2015, when the Law on Associations and Non-governmental Organisations was passed, were minimal, and the new law does not regulate educational programs [14]. Additionally, as of writing, 5,062 NGOs are recorded in the CSO Database Management System of the Cooperation Committee for Cambodia (CCC) [15] compared to 1,928 NGOs registered with official ministries and agencies of the Royal Government of Cambodia in the ODA database. This indicates that many NGOs in Cambodia are not registered with the same authorities but are only found on membership registries [network] like the Cooperation Committee for Cambodia (CCC). Since the NGOs examined in the study vary in organization structure and purpose, the contexts in which they work and the different roles the NGOs play in their respective communities are expected to differ.

2.2. Social-Emotional Learning (SEL)

Social-Emotional Learning (SEL) is learning that prepares youths for intrapersonal and interpersonal relationships that enable them to thrive inside and outside the school environment. SEL has seen burgeoning development and interest in recent decades. Numerous programs established across the globe are designed to target and foster the SEL of youths [5]. Fostering the growth of SEL among students is a key service that educational NGOs can deliver, promoting sustainable development in communities and reducing the inequalities their students face. In the field of education, NGOs have done considerable work. Countries such as India, Ethiopia, and Ghana acknowledge the validity of NGO education programs as complementary to state education [12]. The initiatives of a non-governmental organization in Malaysia were noted to successfully empower students to escape the cycle of poverty through its education programs [16]. In Delhi, India, research identified that programs provided by educational NGOs have cultures more conducive to learning than that of government schools [17]. A case study of an NGO in South Africa demonstrated that efforts of the NGO to provide preparatory schooling to underprivileged students who did not qualify for matriculation directly benefit students from disadvantaged backgrounds and non-confrontationally motivate the government to improve public schools [18].

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Materials

The sample data collected through surveys from SOS contained 33 females and 16 males where the average age is 16, and the sample collected from VDP contained 27 males and 22 females where the average age is 15. SEL levels in students and differences in NGO approaches to education were assessed with interviews, surveys, and observations. The semi-structured interviews contain 9 predetermined baseline questions on 3 dimensions of the NGO, philosophy, policy, and practice. The SEL survey was adapted from Panorama Education with a total of 35 questions in 7 sections: demographics, self-management, social awareness, self-awareness, relationship skills, responsible decision making, and school climate. Usually, each section contains 5 questions. Information regarding the students’ subjective socioeconomic status (SES), years at their respective organizations, and household members were included in the demographics section of the survey as control variables. Then, observations were conducted during lessons and noted carefully. The selection process attempted to incorporate a diverse sample of ages and students; hence, a range of lower-level and higher-level classes was selected in VDP and SOS corresponding to each other in terms of age.

3.2. Procedures and Data Analysis

To begin with, employees with administrative duties and teachers were selected and asked a series of questions in an interview to understand their NGO’s philosophy, policy, and practice. At VDP, 3 interviews were conducted with managers, and 3 interviews were conducted with teachers. At SOS, all of the interviewees had teaching duties. The interviews provide insight to the daily functions, mission, and purpose of the NGOs. This helps with characterizing the organization and understanding the factors that may have an effect on the SEL skills of students at those organizations.

Then, surveys containing questions about demographics and duration of enrollment in conjunction with SEL survey questions adapted from Panorama Education were distributed among selected classes, which contained all classes taught by the teachers interviewed. 10 surveys were sent to each class. To diversify the sample, students from both lower- and higher-level classes were selected. At VDP, the surveys were split between English classes (levels 3, 4, and 5) and Khmer classes (levels 4, 5, and 6). In all, 99 surveys were retrieved, of which 50 came from SOS and 49 from VDP. These surveys are designed to assess students’ SEL skills and provide information about students that can be further examined to show whether there are other factors influencing their SEL skills.

Furthermore, to corroborate information gathered from the interviews and surveys, observations were carried out in classes that were selected to fill out the survey and other classes. All relevant observations made on student-teacher interactions, student appearances, student behavior, classroom procedures, and other actions indicating SEL skills or the facilitation of SEL skills were meticulously noted down. Observations and note-taking lasted whole class sessions, typically one hour long.

The first NGO program involved in the study is the Village Development Program (VDP), an after-school academic enrichment program organized by the NGO Asian Hope. Comparatively, the second program, the SOS Hermann Gmeiner School, is a full-time school aligned with the Cambodian education system belonging to SOS Children’s Villages Cambodia Organization.

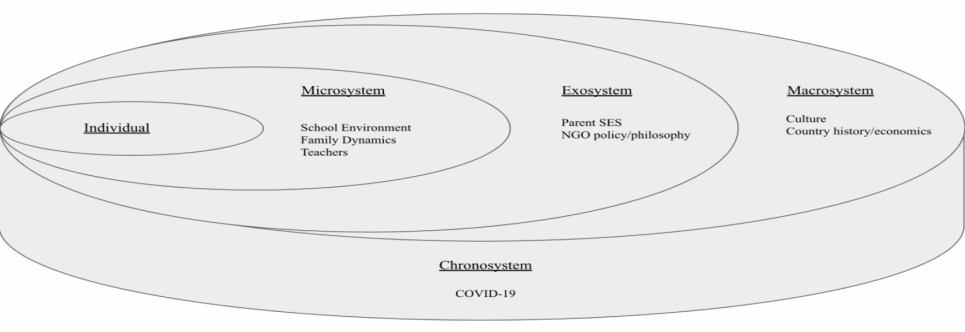

The survey data is analyzed with Graphpad Prism where the t-test, regression analysis, and descriptive statistics were applied. The p-value of the overall analysis was set at 0.05. For the interview and observational text analysis, the Ecological Model was adopted. The model consists of the interrelated microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem. It has been shown to guide specific SEL approaches and studies have recognized that SEL depends on the context and school climate [19-22].

4. Results

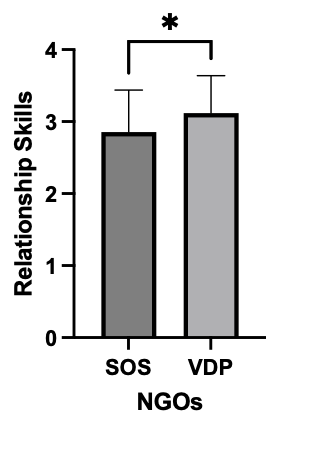

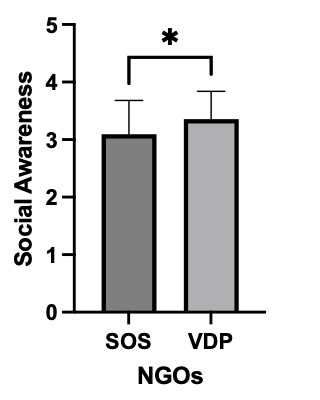

Results of the data analysis indicate that the SEL components between SOS and VDP students did not differ significantly in all core competencies. The author failed to reject the null hypothesis at .05 level of significance. Noticeably, as seen in Table 1, self-management and relationship skills are the two SEL components significantly differing between students in VDP and SOS with p-values of .0155 and .0201 respectively. For relationship skills, students at SOS reported a mean of 2.855 and a standard deviation of .5847, while students at VDP reported a mean of 3.118 and a standard deviation of .5211. Otherwise, other SEL components like self-management, social awareness, self-awareness, and responsible decision making of the two groups of students are equitable.

Table 1: Mean and Significance of SEL levels at VDP and SOS.

Mean + SD (SOS) | Mean + SD (VDP) | P value | Significance | |

Self-Management | 3.630±0.5641 | 3.617±0.6408 | 0.9155 | No |

Social Awareness | 3.090±0.5885 | 3.357±0.4841 | 0.0155 | Yes |

Self-Awareness | 3.170±0.6733 | 3.192±0.6900 | 0.8721 | No |

Relationship skills | 2.855±0.5847 | 3.118±0.5211 | 0.0201 | Yes |

Responsible Decision making | 3.785±0.5825 | 3.820±0.5282 | 0.7568 | No |

School Climate | 3.381±0.4873 | 3.573±0.6547 | 0.0993 | No |

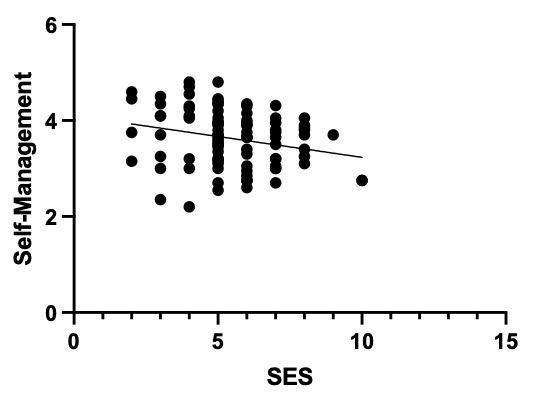

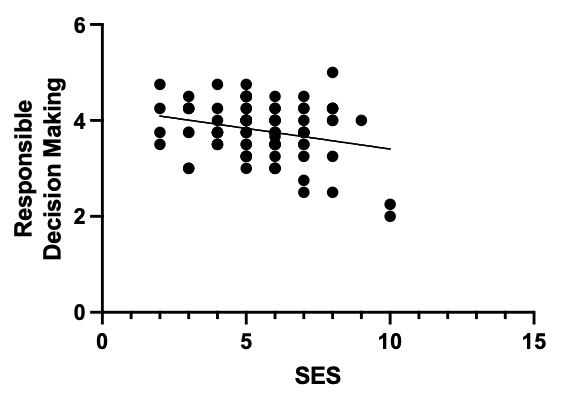

Next, to determine the influences of socioeconomic status (SES) and age, the control variables, on SEL competencies, the correlation between the control variables and the dependent variables are calculated. In Table 2, SES negatively correlates with self-management and responsible decision making. The p-values are .0164 and .0109 respectively. No other SEL modules significantly correlate with SES at the .05 degree of significance, and no SEL module significantly correlates with age at the .05 degree of significance.

Table 2: Correlation between SEL levels and control variables (SES and Age).

SES | Age | |||

Pearson’s r | P value | Pearson’s r | P value | |

Self-Management | -0.2456 | 0.0164* | 0.03586 | 0.7287 |

Social Awareness | -0.1124 | 0.2783 | -0.04522 | 0.6617 |

Self-Awareness | 0.02248 | 0.8288 | 0.06476 | 0.5307 |

Relationship skills | -0.01605 | 0.8773 | 0.02004 | 0.8463 |

Responsible Decision making | -0.2603 | 0.0109* | 0.1448 | 0.1593 |

School Climate | 0.03321 | 0.7494 | 0.04437 | 0.6677 |

Figure 1 and Figure 2 below model the SES–self-management correlation and SES–responsible decision making correlation with lines of best fit. As shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4, an ecological model was created to model the differences between VDP and SOS.

|

|

Figure 1: Self-Management and SES correlation. | Figure 2: Responsible Decision Making and SES correlation. |

|

|

Figure 3: Significance of SOS/VDP Relationship difference. | Figure 4: Significance of SOS/VDP Social Awareness difference. |

5. Discussion

5.1.Social Awareness and Relationship Skills at VDP and SOS

Results show that social awareness and relationship skills at VDP are higher than at SOS. A main difference between the two NGOs is the recruitment of teachers. SOS pays employs full-time teachers who average around 9.7 years of occupation, while VDP relies on part-time volunteers who average around 5.3 years of occupation. However, considering VDP teachers are volunteers who do the job because they resonate with the mission, the teachers at VDP possibly possess a higher degree of commitment and religious affinity in the NGO that could explain the higher social awareness and relationship skills in students. Nonetheless, this does not mean teachers at SOS are less involved or committed to student welfare; in fact, some teachers said that they offer additional support to students outside of school hours. The difference could be the community bonding element of religion and the attachment of children in need to a charitable supporting figure. The system this falls under is the Microsystem. Additionally, the two NGOs differ in approaches to quality education. Noticeably, teachers and organizational features in VDP incorporate religion into their teaching. On Fridays, lessons are on “studying the Bible and soft skills.” In interviews, teachers also expressed their religious connection and desire to engage with students in alinement with their beliefs. In SOS, teachers try to instill moral values in their students as well though it appears to be on a voluntary basis. From observations of SOS classes, the teachers manage their classes stricter than VDP. That may be necessary for regular schools, but not academic enrichment programs since students who go to VDP for academic enrichment do so voluntarily.

Generally, both NGOs provide education intending to improve student academic attainment and employability, but VDP is more religiously influenced and free to incorporate additional components in their program. Those are increased measures and activities that could encourage SEL, but SOS follows a standard curriculum which allows for less possibilities for deliberate attempts to increase SEL competencies. NGO philosophy and policy is the exosystem level of influence.

5.2.The Correlation Between SES and Self-Management and Responsible Decision Making

Across both NGOs, self-management and responsible decision making negatively correlate with SES. An explanation for this is that students with higher SES do not have as many family responsibilities compared to students with lower SES who might be expected to perform tasks or household duties. As a result, students from a lower SES background exercise self-management and decision making more frequently than students from a higher SES background. Moreover, students from a higher SES background are more likely to have parental guidance in decision-making. Students with a higher SES could have been subjected to more imposed parental control that leads to weaker self-management and responsible decision making. The negative correlation between self-management and responsible decision making could be attributed to parent SES, which belongs to the Exosystem.

5.3.Similar SEL Components Between SOS and VDP Students in All Core Competencies

Some SEL skills across students enrolled in educational programs of two NGOs did not differ significantly despite the students being exposed to different styles of instruction. The phenomenon can be examined from the Macrosystem and Chronosystem standpoint. SEL skills are formed in the context of culture and the individual’s society. Components of SEL such as self-management, self-awareness, and responsible decision making could have been cultivated by Cambodian cultural ideals such as hard work, academic achievement, and filial piety. Situated in the economy of a developing nation, the students who belong to the demographic targeted by VDP and SOS are commonly less economically advantaged. Being in that situation, certain aspects of their SEL could have been encouraged by their circumstances, as they bear greater responsibilities and mature earlier. Importantly, against the backdrop of COVID-19, VDP has to suspend its program multiple times and SOS implemented COVID-related protocols such as online learning and regular testing. The compounded effects of COVID-19, the Chronosystem, on mental health, self-management, and SEL are prospective research directions. The ecological model below summarizes the discussion in systems of the ecological model.

Some SEL skills across students enrolled in educational programs of two NGOs did not differ significantly despite the students being exposed to different styles of instruction. The phenomenon can be examined from the Macrosystem and Chronosystem standpoint. SEL skills are formed in the context of culture and the individual’s society. Components of SEL such as self-management, self-awareness, and responsible decision making could have been cultivated by Cambodian cultural ideals such as hard work, academic achievement, and filial piety. Situated in the economy of a developing nation, the students who belong to the demographic targeted by VDP and SOS are commonly less economically advantaged. Being in that situation, certain aspects of their SEL could have been encouraged by their circumstances, as they bear greater responsibilities and mature earlier. Importantly, against the backdrop of COVID-19, VDP has to suspend its program multiple times and SOS implemented COVID-related protocols such as online learning and regular testing. The compounded effects of COVID-19, the Chronosystem, on mental health, self-management, and SEL are prospective research directions. The ecological model below summarizes the discussion in systems of the ecological model.

Figure 5: The ecological model that summarizes the discussion from five standpoints of individual, microsystem, exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem.

6. Conclusion

This research set out to compare different SEL attainment levels in students enrolled in two different NGO educational programs in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. SEL proficiency and demographic attributes are measured using a survey, and NGO structural and program differences are explored through semi-structured interviews with teachers and managers. The results show higher levels of social awareness and relationship skills within VDP. Regression analysis reveals a negative correlation between the socioeconomic control with self-management and responsible decision making.

Under COVID conditions and considering limitations to resources, the sample could not be expanded. And the study employed purposeful sampling based on the class level. That might be a limitation to ecological validity as the methods used might possibly introduce sampling biases. Besides, at SOS, the observations took place on one school day. At VDP, the observations occurred over three visits and classes observed spanned different time periods. Therefore, the timing limits the observations to a particular session on a particular day during a particular time slot. It is not a comprehensive observation of the students over an extended length of time through many sessions and it is also limited to observations on indications of SEL skills or the facilitation of SEL skills in the classrooms. Moreover, the completion of the surveys that were sent out was not absolute. One survey was not returned, and some questions on surveys that were submitted were left unanswered. Due to the fact that interviewees were Khmer speakers, the interviews had to be transcribed and translated into English after being recorded. During the process, some subtleties were lost in translation.

References

[1]. Cambodian Rehabilitation and Development Board Council for the Development of Cambodia. (2020) Development Cooperation and Partnerships Report. http://cdc-crdb.gov.kh/en/officials-docs/documents/DCPR-2018-English.pdf

[2]. Chan, C. (2019) The Roles and Functions Of NGOs in Children’s Education. UC Occasional Paper Series, 3(2), 27–58. https://uc.edu.kh/Occasional_Paper_Series/December%202019/Second%20article.pdf

[3]. Pellini, A. (2005) Decentralisation of education in Cambodia: searching for spaces of participation between traditions and modernity. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 35(2), 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057920500129866

[4]. Jagers, R.J., Rivas-Drake, D. and Williams, B. (2019) Transformative Social and Emotional Learning (SEL): Toward SEL in Service of Educational Equity and Excellence. Educational Psychologist, 54(3), 162–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2019.1623032

[5]. Weissberg, R.P., Durlak, J.A., Domitrovich, C.E. and Gullotta, T.P. (Eds.). (2015) Social and emotional learning: Past, present, and future.

[6]. Zins, J.E. (Ed.). (2004) Building academic success on social and emotional learning: What does the research say?. Teachers College Press.

[7]. Calhoun, B., Williams, J., Greenberg, M., Domitrovich, C., Russell, M.A. and Fishbein, D.H. (2020) Social Emotional Learning Program Boosts Early Social and Behavioral Skills in Low-Income Urban Children. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.561196

[8]. Weems, C.K. (2021) Evidence-Based Program Selection and Duration of Implementation of Social-Emotional Learning as Related to Student Growth and Non-Academic Outcomes [Doctoral dissertation, East Tennessee State University]. Proquest. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3933

[9]. Banks, N., Hulme, D. and Edwards, M. (2015) NGOs, States, and Donors Revisited: Still Too Close for Comfort? World Development, 66, 707–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.09.028

[10]. Brass, J.N., Longhofer, W., Robinson, R.S. and Schnable, A. (2018) NGOs and international development: A review of thirty-five years of scholarship. World Development, 112, 136–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.07.016

[11]. Edwards, M. and Hulme, D. (1996) Too close for comfort? The impact of official aid on nongovernmental organizations. World Development, 24(6), 961–973. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750x(96)00019-8

[12]. Rose, P. (2009) NGO provision of basic education: alternative or complementary service delivery to support access to the excluded? Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 39(2), 219–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057920902750475

[13]. Mitlin, D., Hickey, S. and Bebbington, A. (2005) ‘Reclaiming development? NGOs and the challenge of alternatives’, Background paper for the conference on Reclaiming Development: Assessing the Contribution of NGOs to Development Alternatives, Manchester June 27–29 (draft paper).

[14]. Curley, M. (2018) Governing Civil Society in Cambodia: Implications of the NGO Law for the “Rule of Law.” Asian Studies Review, 42(2), 247–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2018.1457624

[15]. Cooperation Committee for Cambodia. (n.d.). CCC NGO Database. CSO Database Management System. Retrieved July 27, 2022, from https://www.ccc-cambodia.org/en/ngodb

[16]. Hashim, A.T., Osman, R. and Badioze-Zaman, F.S. (2016) Poverty challenges in education context: a case study of transformation of the mindset of a non-governmental organization. International Journal of ADVANCED AND APPLIED SCIENCES, 3(11), 40–46. https://doi.org/10.21833/ijaas.2016.11.008

[17]. Kumar, A. (2019) Cultures of learning in developing education systems: Government and NGO classrooms in India. International Journal of Educational Research, 95, 76–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.02.009

[18]. Msindo, E.M. (2014) The role of civil society in advancing education rights : the case of Gadra Education, Grahamstown, South Africa [Master’s Thesis, Rhodes University]. South East Academic Libraries System. http://hdl.handle.net/10962/d1016500

[19]. Aston, H.J. (2014) An ecological model of mental health promotion for school communities: adolescent views about mental health promotion in secondary schools in the UK. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 16(5), 289-307.

[20]. McCormick, M.P., Cappella, E., O’Connor, E.E. and McClowry, S.G. (2015) Context Matters for Social-Emotional Learning: Examining Variation in Program Impact by Dimensions of School Climate. American Journal of Community Psychology, 56(1–2), 101–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-015-9733-z

[21]. Meyers, A.B., Tobin, R.M., Huber, B.J., Conway, D.E. and Shelvin, K.H. (2015) Interdisciplinary collaboration supporting social-emotional learning in rural school systems. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 25(2-3), 109-128.

[22]. Trach, J., Lee, M. and Hymel, S. (2018) A social-ecological approach to addressing emotional and behavioral problems in schools: Focusing on group processes and social dynamics. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 26(1), 11-20.

Cite this article

Zhu,H. (2023). How Cambodian NGOs’ Education Systems Cultivate SEL: A Comparative Analysis Based on Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Model. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,9,17-25.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Cambodian Rehabilitation and Development Board Council for the Development of Cambodia. (2020) Development Cooperation and Partnerships Report. http://cdc-crdb.gov.kh/en/officials-docs/documents/DCPR-2018-English.pdf

[2]. Chan, C. (2019) The Roles and Functions Of NGOs in Children’s Education. UC Occasional Paper Series, 3(2), 27–58. https://uc.edu.kh/Occasional_Paper_Series/December%202019/Second%20article.pdf

[3]. Pellini, A. (2005) Decentralisation of education in Cambodia: searching for spaces of participation between traditions and modernity. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 35(2), 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057920500129866

[4]. Jagers, R.J., Rivas-Drake, D. and Williams, B. (2019) Transformative Social and Emotional Learning (SEL): Toward SEL in Service of Educational Equity and Excellence. Educational Psychologist, 54(3), 162–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2019.1623032

[5]. Weissberg, R.P., Durlak, J.A., Domitrovich, C.E. and Gullotta, T.P. (Eds.). (2015) Social and emotional learning: Past, present, and future.

[6]. Zins, J.E. (Ed.). (2004) Building academic success on social and emotional learning: What does the research say?. Teachers College Press.

[7]. Calhoun, B., Williams, J., Greenberg, M., Domitrovich, C., Russell, M.A. and Fishbein, D.H. (2020) Social Emotional Learning Program Boosts Early Social and Behavioral Skills in Low-Income Urban Children. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.561196

[8]. Weems, C.K. (2021) Evidence-Based Program Selection and Duration of Implementation of Social-Emotional Learning as Related to Student Growth and Non-Academic Outcomes [Doctoral dissertation, East Tennessee State University]. Proquest. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3933

[9]. Banks, N., Hulme, D. and Edwards, M. (2015) NGOs, States, and Donors Revisited: Still Too Close for Comfort? World Development, 66, 707–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.09.028

[10]. Brass, J.N., Longhofer, W., Robinson, R.S. and Schnable, A. (2018) NGOs and international development: A review of thirty-five years of scholarship. World Development, 112, 136–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.07.016

[11]. Edwards, M. and Hulme, D. (1996) Too close for comfort? The impact of official aid on nongovernmental organizations. World Development, 24(6), 961–973. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750x(96)00019-8

[12]. Rose, P. (2009) NGO provision of basic education: alternative or complementary service delivery to support access to the excluded? Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 39(2), 219–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057920902750475

[13]. Mitlin, D., Hickey, S. and Bebbington, A. (2005) ‘Reclaiming development? NGOs and the challenge of alternatives’, Background paper for the conference on Reclaiming Development: Assessing the Contribution of NGOs to Development Alternatives, Manchester June 27–29 (draft paper).

[14]. Curley, M. (2018) Governing Civil Society in Cambodia: Implications of the NGO Law for the “Rule of Law.” Asian Studies Review, 42(2), 247–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2018.1457624

[15]. Cooperation Committee for Cambodia. (n.d.). CCC NGO Database. CSO Database Management System. Retrieved July 27, 2022, from https://www.ccc-cambodia.org/en/ngodb

[16]. Hashim, A.T., Osman, R. and Badioze-Zaman, F.S. (2016) Poverty challenges in education context: a case study of transformation of the mindset of a non-governmental organization. International Journal of ADVANCED AND APPLIED SCIENCES, 3(11), 40–46. https://doi.org/10.21833/ijaas.2016.11.008

[17]. Kumar, A. (2019) Cultures of learning in developing education systems: Government and NGO classrooms in India. International Journal of Educational Research, 95, 76–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.02.009

[18]. Msindo, E.M. (2014) The role of civil society in advancing education rights : the case of Gadra Education, Grahamstown, South Africa [Master’s Thesis, Rhodes University]. South East Academic Libraries System. http://hdl.handle.net/10962/d1016500

[19]. Aston, H.J. (2014) An ecological model of mental health promotion for school communities: adolescent views about mental health promotion in secondary schools in the UK. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 16(5), 289-307.

[20]. McCormick, M.P., Cappella, E., O’Connor, E.E. and McClowry, S.G. (2015) Context Matters for Social-Emotional Learning: Examining Variation in Program Impact by Dimensions of School Climate. American Journal of Community Psychology, 56(1–2), 101–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-015-9733-z

[21]. Meyers, A.B., Tobin, R.M., Huber, B.J., Conway, D.E. and Shelvin, K.H. (2015) Interdisciplinary collaboration supporting social-emotional learning in rural school systems. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 25(2-3), 109-128.

[22]. Trach, J., Lee, M. and Hymel, S. (2018) A social-ecological approach to addressing emotional and behavioral problems in schools: Focusing on group processes and social dynamics. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 26(1), 11-20.