1. Introduction

Political corruption refers to the misuse of public power for private gain or unfair advantages [1, 2, 3]. Corruption in politics can occur at different levels, ranging from local to national. It can have substantial adverse impacts on stability, including destroying public confidence in government institutions, aggravating social inequalities, subverting the rule of law, and diminishing the quality of public services [2, 4]. Globally, the establishment of independent institutions to address the abuse of entrusted authority for personal gains has gained prominence, reflecting a growing recognition that corruption is a pressing issue. This popularity is explained by increased effectiveness and efficiency in tackling corruption-related challenges by pooling expertise and resources, and their independence enables them to conduct investigations impartially. Over the past decade, South Korea has outperformed most of its regional neighbors in various governance dimensions; however, it has long struggled with corruption controls and public confidence [4]. Realizing the critical nature of tackling corruption at the national level, South Korea has implemented anti-corruption measures to upgrade its systems across society. As a result, it gained global notoriety for its commitment to combating corruption, predominantly due to the creation of the Anti-Corruption and Civil Rights Commission (ACRC). This study seeks to elucidate and evaluate the primary factors that have contributed to the commission’s identification as a leading organization for the pan-governmental anti-corruption initiative. The paper first describes South Korea’s political culture and systemic corruption, before turning to an in-depth analysis of the ACRC. The significance of this study is to provide insights into good anti-corruption practices and innovative approaches that can be adopted in other countries, leading to more positive outcomes.

2. State of Governance in South Korea

Although South Korea meets the basic institutional criteria of democracy, its deeper structural and cultural transformations are lagging in progress. South Korea has a longstanding legacy under state-corporatist arrangements of the authoritarian regime, with regulated private entities and bureaucrats enjoying intimate bonds [4]. Peter Evans stated that South Korea’s success in attaining rapid industrialization and development was inseparable from embedded autonomy, in which the state actively participated in bureaucratic business networks while simultaneously maintaining a degree of independence from vested interests. The embeddedness ensured that national planning is aligned with the needs of the private sector. However, it exposed the country to a higher risk of corruption as abuse of power is more likely and whistleblowing is extremely difficult. This “partnership” shifted as major business groups emancipated themselves from government patronage after they amassed immense wealth and influence [4, 5]. They became large conglomerates known as chaebols, wielding sizable economic and political influence in the country [6]. Another factor that explains why corruption has long been a dominant feature in South Korean politics is competitive factionalism, which breeds perverse incentives within the political environment that created a climate where corruption goes unchecked and unaddressed [4, 7].

Owing to corruption, several cases of human-made financial disasters and tragedies have taken place in South Korea, namely the Korean Financial Crisis of 1997, the Savings Bank Scandal of 2011, the Sewol Ferry Disaster in 2014, and the Oxy Reckitt Benckiser Humidifier Disinfectant Disaster [6]. These serious incidents sparked an uproar among the citizens and increased intolerance of corruption. The rising discontent and distrust over the South Korean government’s devotion to controlling collusive ties and industry influence continue to fracture Korean society, which led to its delivery of strongly worded pledges toward preventing regulatory failures and eliminating corruption in the public sector [8, 9]. As a result, South Korea has undergone considerable efforts over the past decade to mitigate the risk of corruption, which fall into three categories. First, through enacting and refining laws to strengthen its anti-corruption framework, the country underwent multiple transparency-oriented by reforms aimed at fostering a healthier political climate and a more transparent government. Second, to forestall unethical practices and defend public welfare, South Korea has made advances in reinforcing its institutional and legal framework. Third, instilling an ethical culture rooted in integrity among public officials has been the focus of South Korea. The creation of the ACRC is found to serve functions in all three categories.

3. The Pan-Governmental Anti-Corruption Body

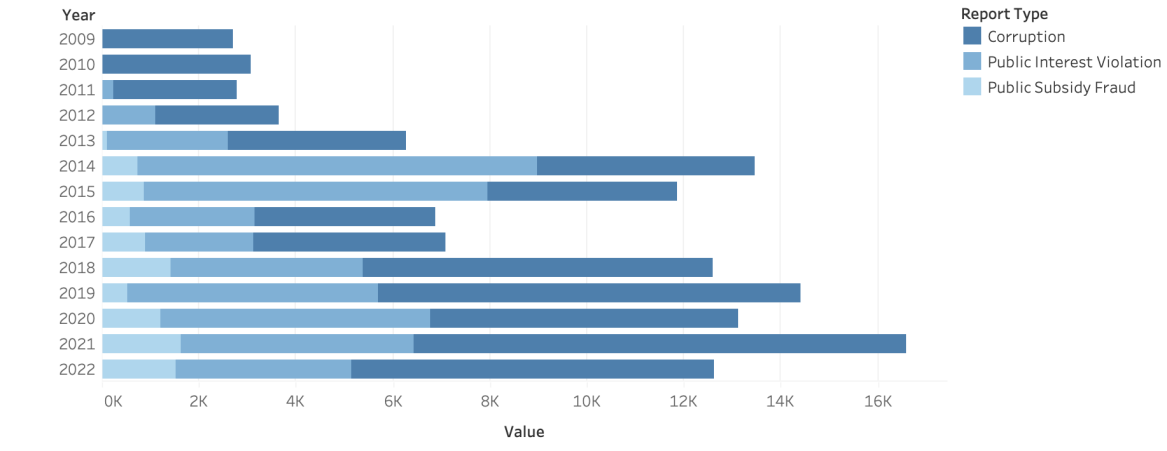

The ACRC is South Korea’s anti-corruption body, tasked with improving the corruption-prone environment and cracking down on rule-breakings. It took place in 2008 after merging the Administrative Appeals Commission, the Korea Independent Commission Against Corruption, and the Ombudsman of Korea [10]. It has a total of 15 commissioners whose independence is guaranteed by the law [10]. The commission’s principal objectives are to mediate collective civil complaints, expose corruption weaknesses in governmental agencies, and devise and implement anti-corruption policies [10]. By bringing all three organizations under its umbrella, the ACRC can conveniently and effectively discharge its role as a corruption prevention ombudsman. Its contribution to South Korea’s restoration of its international standing in anti-corruption continues to receive attention [9, 11]. Since its inception, it has reviewed a copious number of reports of corruption (70,555), violations of the public interest (47,063), and public subsidy fraud (9,498), as shown in Figure 1. It is believed that the ACRC is recognized globally as a leader in anti-corruption initiatives because of its multifaceted approach to controlling corruption: comprehensive preventive measures, robust whistleblower protection, extensive public education, and frequent international cooperation.

Figure 1: Annual Number of Reports Processed by the ACRC from Inception to 2022 [10].

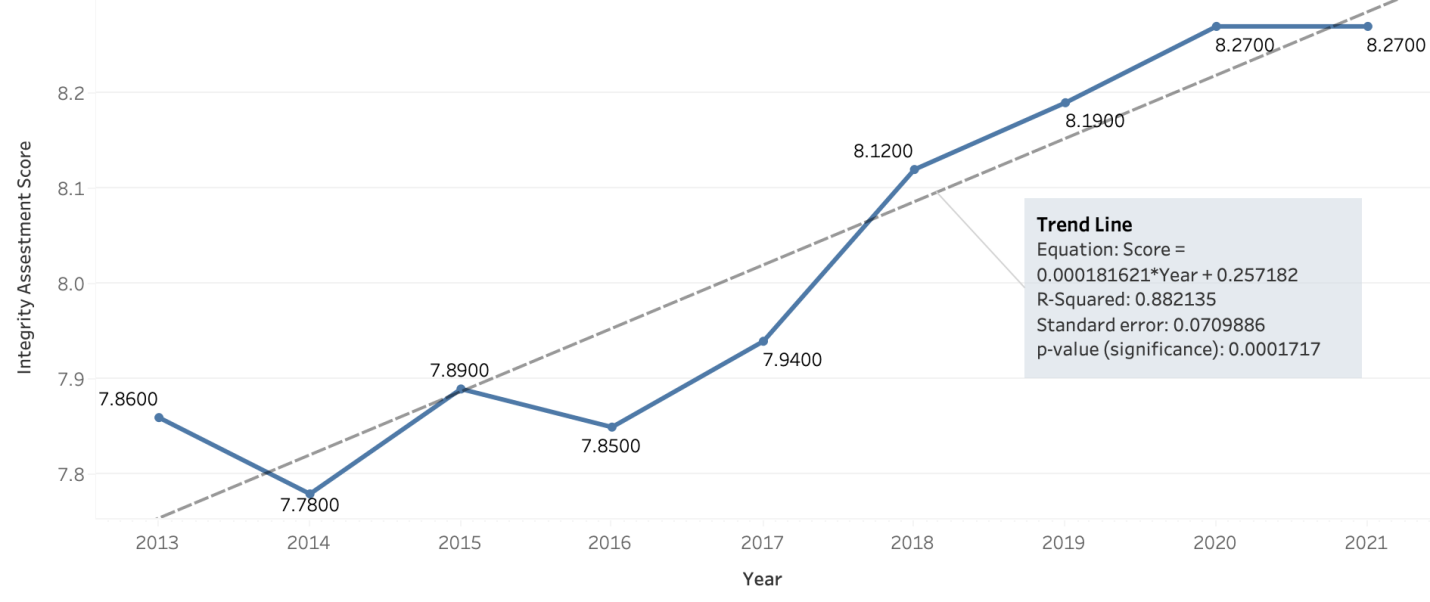

With firm determination toward anti-corruption, the ACRC has pushed unremitting efforts for nationwide systemic and comprehensive reforms. It has upgraded its institutional foundation for the preemptive elimination of corruption risks, by aiding in the development of numerous laws intended to permeate integrity, accountability, and transparency into the public sector. Apart from devising anti-corruption policies, the Code of Conduct for Public Officials was also formulated by the ACRC. For duty-related officials, it stipulates that they ought to practice political impartiality, confidentiality, fairness, compassion, and good faith [10]. Defining the boundaries and standards that civil servants must adhere to reduces corruption risks and enhances accountability by making it simpler to spot and investigate ethical misconduct. Moreover, the commission has conducted a multitude of assessments to encourage public organizations to voluntarily combat corruption. The ACRC has executed scientific assessments of the integrity of public institutions and published the results annually since 2002 [12, 13]. The evaluation relies on surveying citizens regarding their firsthand experience with public service, as well as interviews with internal public officials and selected professionals [10,12]. As Figure 2 illustrates, the comprehensive integrity (external and internal) score has steadily increased since 2016, suggesting an upward trend. To determine sources of corruption in existing laws and proposed new rules, the ACRC conducts Corruption Risk Assessments (CRAs) for the purpose of advising on applicable countermeasures [14]. Among 182 statutes, a total of 406 corruption-contributing factors were discovered by the CRA in 2021 [13].

Figure 2: Integrity Assessment Results from 2013 to 2021 [10].

It is widely accepted that whistleblowers provide frontline protection against dishonesty and immorality within the public sector [9, 15]. The ACRC’s investment in professionalizing whistleblower protection is noteworthy to normalize whistleblowing and encourage more people to come forward and express their concerns. The commission launched a well-designed public interest reporting system in 2011 and has continued to advance the system, to increase the convenience and accessibility of filing and consultation [10]. The ACRC has made seven revisions and added legal instruments to strengthen the protection of whistleblowers at all levels. It has maintained its efforts to guarantee that personal protection measures are provided, secrets and identities are safeguarded through proxy reporting, legal services reduce or exempt, and courage is rewarded. Furthermore, to construct a sustainable system that guarantees national integrity, the ACRC also engages in awareness building and international cooperation. The commission launched the Anti-Corruption Training Institute in 2013 and mandated all public officials to receive professional integrity education [10]. Systemic training ensures public officials understand they must act as fiduciary agents of the citizenry and to increase their consciousness regarding the detrimental effects of corruption. It has also ratified several international anti-corruption conventions, demonstrating its commitment to global anti-corruption efforts and cooperation with other signatories [13]. It is actively involved in international and regional anti-corruption initiatives and works bilaterally with institutions around the world to share knowledge and build partnerships. In spite of the accomplishments, corrupt practices remian present, and public skepticism about the extent of the ACRC’s work in promoting government integrity persists, as opinion polls continue to show a lack of faith in public organizations.

4. The Effectiveness of the ACRC

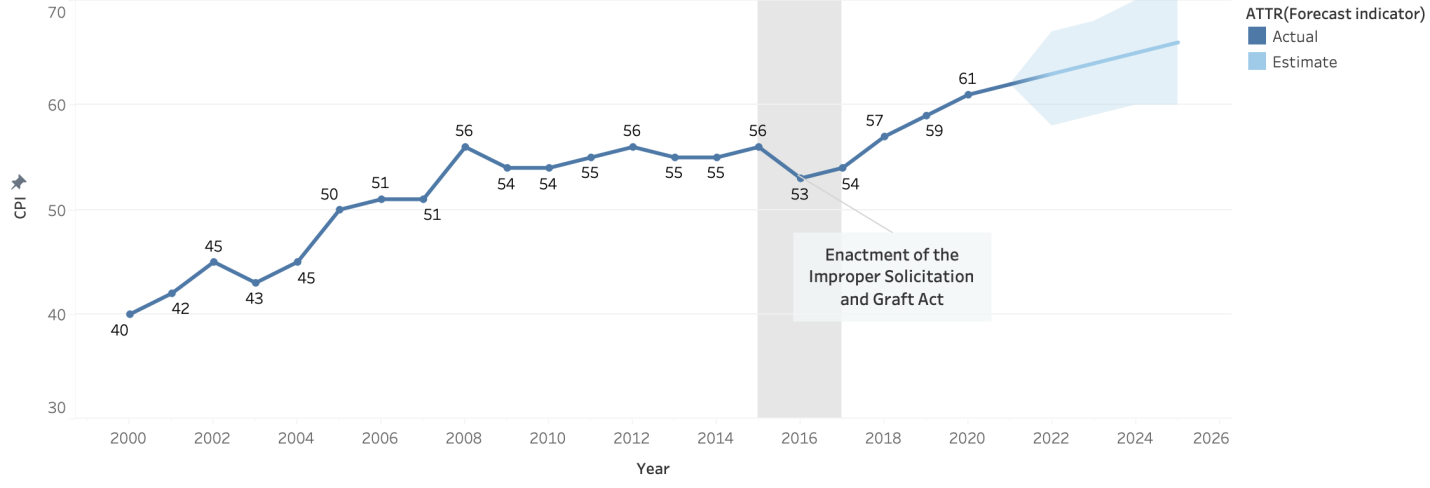

There is a lack of explicit performance indicators to measure the effectiveness of the ACRC. This paper takes an indirect approach, inferring its impact by analyzing international indices on outcomes: the Corruption Perceptions Index, the Index of Public Integrity, the Bribery Risk Matrix, and the Open Budget Index. The first one is the Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI). The CPI is a globally representative index published annually that ranks countries based on public perceptions of public sector corruption as determined by expert assessments and opinion polls [16]. The index is assessed out of 100, with a score of 100 representing a perfectly clean governance system. In 2012, Korea ranked 45th out of 176 countries with a score of 56. It now ranks 31st among 180 countries with a score of 63. As depicted in Figure 4, the score has risen for six consecutive years and is expected to continue rising in the coming years, as forecast by exponential smoothing. Scholars tend to attribute this achievement to the government’s strong commitment to augmenting integrity and national-level corruption prevention efforts [9, 17], but fail to highlight that the ACRC has played a leading role in its ongoing pan-government anti-corruption reform movement. This improvement is mainly thanks to the Unfair Solicitation and Corruption Act introduced by the ACRC, clashing with Korean traditions. The enactment and enforcement of laws in 2016 have greatly increased the sense of integrity in the public sector [10]. This can be confirmed by the results of public opinion surveys. A month after the law went into effect, a poll by Gallup Korea showed that 71 percent of respondents supported the law [18]. Among those who supported the law, the largest portion (31 percent) cited the law assistance in eliminating injustice and corruption. Another 17 percent expressed the belief that the law will make society transparent and clean, and 14 percent said it will reduce unscrupulous incentives for those in power. In addition, according to a recent People’s Idea Box survey of 4,482 participants, 91.2 percent felt the law had a positive impact on society [10].

Figure 3: South Korea’s CPI from 2000 to 2021 and Forecast Trend to 2026 [16].

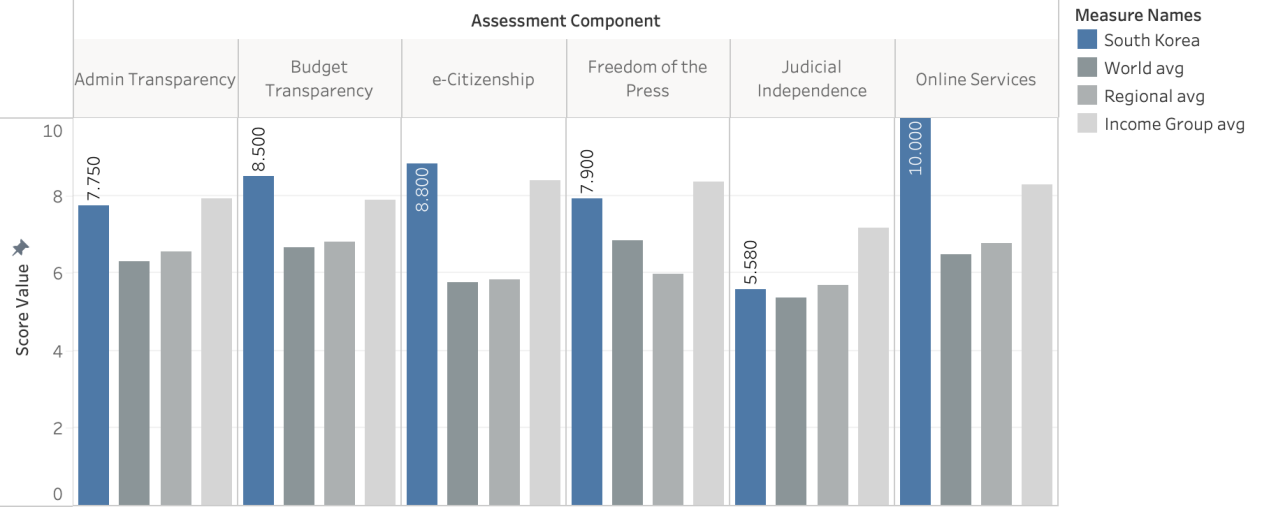

The second metric is the Index of Public Integrity (IPI) generated by the Corruption Risk Forecast. The IPI assesses a society’s capacity to address corrupt practices and utilize public resources with integrity [20]. This capacity is contingent upon the ability of the public sector to minimize the potential for abuse of influence and the ability of society to hold its government accountable [19]. The IPI score is the average of the six component scores: administrative transparency, online services, budget transparency, judicial independence, freedom of press, and e-citizenship [19]. The score takes value between 1 and 10, with higher values representing better performance. In 2021, South Korea ranked 19th among 114 countries with a score of 8.09 and compared favorably to most of its neighbors. It is one of the few countries to achieve such a high level of good governance in contemporary times. Despite some high-level scandals in recent years, it has demonstrated positive evolution in multiple components [20]. As Figure 6 indicates, it has the highest score of online services in the world and the ACRC is a major driver. The ACRC has been proactive in adopting digital innovations to provide easy avenues for reporting corruption-related issues and to boost civic engagement via the use of various online platforms [10, 13]. ACRC Chairperson Hyun-Heui Jeon reveals that the commission plans to advance its digital platform by integrating cutting-edge technologies to accelerate the resolution of reports [10].

Figure 4: South Korea’s Index of Public Integrity Compared to the Averages [19].

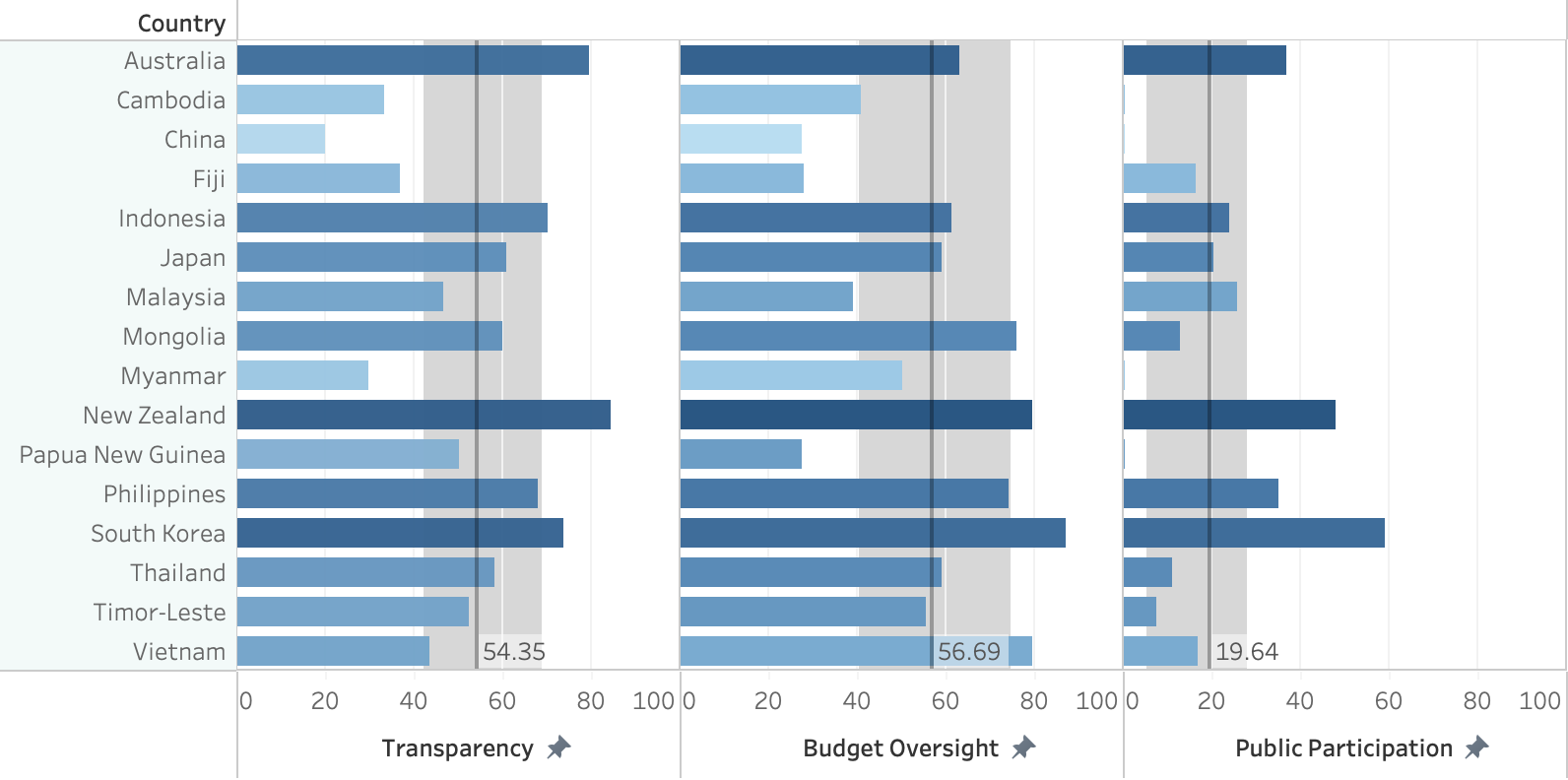

Another indicator is the Bribery Risk Matrix (BRM) released by TRACE International. BRM measures business bribery risk in 194 jurisdictions [21]. In 2022, South Korea took 18th place and 2nd place in Asia. Its ranking rose for 6 years in a row. It is classified as the country group of ‘low risk’ in terms of bribery risk, which implies a clean society where political and economic classes uphold high standards of ethics and integrity [21]. A low bribery risk is also associated with robust anti-corruption laws, a solid institutional framework, and a healthy political culture, suggesting the efforts of the ACRC have paid off. The Open Budget Survey (OBS) 2021 conducted by the International Budget Partnership also proves greater transparency and improved interactions between citizens and public administration [22]. It is the world’s only independently comparable measure of transparency, public participation, and oversight of government budget decision-making [22]. In accordance with the criteria of these three dimensions, the OBS inspects the adequacy of government budget allocations and budgetary control, the availability of formal opportunities for public involvement in the budget process, and the role that auditing institutions play in the budget process in providing appropriate oversight [22]. While the survey itself does not directly examine corruption, participatory budgeting is linked to corruption prevention. A high level of budgetary opacity provides a safe haven for corrupt actors. According to the OBS, South Korea ranked 11th in transparency, 1st in public participation, and 3rd in budget oversight. Its high ranking, portrayed by Figure 6, showcases that the anti-corruption system pushed by the ACRC works effectively in increasing public participation and awareness during the budget monitoring phase, preventing the misuse of public funds. Beyond these indices, it is worth noting that the very existence of the ACRC is a deterrent against corruption, as it is a symbol of political will against encroachment on the public interest, restoring public confidence in the system.

Figure 5: Open Budget Indices on Budget Transparency, Public Participation and Oversight in East Asia and the Pacific [22].

5. Limitations of ACRC and Countermeasures

The ACRC’s anti-corruption reform has attracted worldwide attention. But it encounters criticism. A social satisfaction survey by Seoul National University in 2021 found that more than 58 percent of respondents were unhappy with the political class, largely due to the immorality and corruption of political parties [5]. An empirical study on public perceptions of corruption in East Asia attributes widespread negative attitudes to the South Korean government’s authoritarian past [23]. This explanation is further elaborated by an analysis of drivers of trust in government institutions in South Korea conducted by the OECD. The study finds that although the country performs comparatively well in several existing measures of the quality of public administration, public trust is relatively low [24]. Yi and Jeong (2013) also find that the issue of low trust in South Korea is primarily linked to the elevated expectations following the transition from an authoritarian regime to democratization, entrenched political corruption in society, and harsh criticism toward the government by the mass media. Hence, the ongoing public ire directed at the political class in Korea is not an unequivocal indication that the ACRC is a weak institution. It is also worth mentioning that in the current political climate, expressing trust in any government is likely to elicit at least mild social disapproval [2]. Another popular criticism is that since the establishment of the ACRC, there have been seven high-profile political scandals involving distinguished political figures in South Korea, so it is ineffective. The most widely reported case was the political scandal involving President Park Geun-hye in late 2016, referred to as the “Choi Soon-sil Gate” [20]. The case led to the removal of President Park Geun-Hye for abuse of power, who was arrested on corruption charges in 2017 [20]. However, the occurrence of political scandals cannot be conclusive evidence that the ACRC is ineffective as corruption is a complex issue that cannot be fully eradicated with the ACRC alone – it requires a collective effort from various institutions and society as a whole. Corruption cannot be eradicated in economically vibrant societies [2, 24]. It must be contained and controlled. Studies have discovered a positive correlation between a country’s economic vitality and market players’ exposure to illicit shortcuts [25, 26].

Nonetheless, this study acknowledges that the ACRC has its limitations. On the surface, as an independent body, the ACRC is granted operational and decision-making independence. The autonomy should shield it from political interference and vested interests; however, political interference remains a concern with the ACRC. But it is a quasi-governmental organization whose budget is allocated by the government [27]. Scholars explain that ACRC’s independence is severely compromised due to its appointment process, as the president plays a dominant role in selecting ACRC commissioners, putting impartiality in question [11, 27]. Another concern is that the ACRC has restricted power, which undermines its effectiveness in curbing corruption. It has no independent mandate to initiate investigations, can only act on complaints. It also lacks direct prosecutorial power, meaning it relies on other agencies, such as the Supreme Prosecutors’ Office (SPO), to take legal actions [4, 27]. This often leads to unnecessary bureaucratic hurdles and delays. In addition, the ACRC has been criticized for not having an adequate budget and personnel to carry out its mandate efficiently and effectively. Insufficient resources are believed to hamper the committee’s ability to conduct thorough investigations, enforce preventive measures, and handle heavy workloads.

To address these concerns, South Korea should consider emulating its neighbors, Singapore and Hong Kong, which are consistently rated among the least corrupt nations according to global governance indices. In 1952, the anti-corruption division of the Singapore police force was reorganized into the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB) [28]. The bureau is recognized as a source of inspiration for governments throughout Asia and beyond due to its independence and professionalism [28]. Multiple mechanisms protect the CPIB’s independence: it directly reports to the Prime Minister’s office and has its own budget [29]. If the then-government interferes with the CPIB investigation, the CPIB can directly seek the consent of the President to proceed with the investigation [30]. Additionally, CPIB officers are granted extensive investigative authority, including the power to arrest individuals suspected of corruption and the ability to investigate the suspect’s financial accounts or residence for evidence [30]. Another example worth examining is Hong Kong’s Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC), which has a reputation for being one of the most effective anti-corruption agencies in the world [29]. The ICAC head, who reports directly to Hong Kong’s chief executive, is kept in the dark about specific investigations until the final stages to shield the ICAC from potential political interference [31]. Complementing its investigative powers is the ability to arrest, search and seize property linked to corruption [29]. Drawing on the positives of these two agencies, the ACRC needs greater autonomy, broader and more immediate powers, and sufficient personnel and funds to deal with corruption cases. The proposed first step is to expand its investigative authority by bringing the Corruption Investigation Office for High-ranking Officials (CIO), which is in charge of investigating allegations and prosecuting crimes involving high-ranking officials or their families, into the ACRC. In the meantime, the commission ought to keep championing closer cooperation between the ACRC and law enforcement agencies to facilitate information sharing and joint investigations. Then, it must reinforce its safeguards against undue political influence, such as by granting it financial autonomy and legal protection for its personnel, so that it can carry out its duties without fear of reprisal.

6. Conclusion

This study seeks to shed light on the elements that have contributed to the success of the ACRC while evaluating its effectiveness. The paper begins by explaining that South Korea has wrestled “elite cartel” forms of corrupt institutions and is vigorously pressing for a more honest and accountable government to regain public trust in public institutions, break away from its authoritarian past, and mitigate unethical practices. The country has made observable progress in the fight against corruption, with the creation of the ACRC being an integral component. Then discuss the holistic approach the ACRC employed to systemic anti-corruption reforms to strengthen its institutional base: comprehensive preventive measures, thorough protection for whistleblowers, exhaustive public education, and ongoing international cooperation. The study validated the effectiveness of the ACRC by analyzing four international indices, all of which point to improvements brought about by the commission’s anti-corruption initiatives. Its potential, however, is hampered by reduced independence and a lack of power and resources to expand its investigative reach. Nonetheless, combating corruption is a drawn-out struggle, and cultivating a culture of integrity requires unceasing efforts. Faced with the challenges ahead, the government must remain vigilant, starting with offering the ACRA prosecution authority and upgrading its internal resources. This study recognizes the limitations and incompleteness of its impact analysis of the ACRC, as it relies on indirect international indices to infer its effectiveness and does not assess explicit performance indicators such as service quality, timeliness, and stakeholder engagement. Future research is needed. The absence of comprehensive quantitative analysis is a result of the paucity of available performance data of the ACRC available for access in English. It is also worth noting that the paper is built on English literature works.

Acknowledgment

This paper explores and expands on topics taught in the Legal Aspects of Public Agency Decision-Making class offered at Cornell University – special thanks to Professor Daniel Manne for his thought-provoking discussions. I would also like to express my gratitude to those who have supported me through my academic journey. Their wisdom and experience have inspired me throughout my studies.

References

[1]. Jain, A. K. (2001). Corruption: A review. Journal of economic surveys, 15(1), 71-121.

[2]. Min, K. S. (2023). The impact of corruption on government performance: evidence from South Korea. Crime, Law and Social Change, 79(3), 319-345.

[3]. Philp, M. (1997). Defining political corruption. Political Studies, 45(3), 436-462.

[4]. Kalinowski, T. (2016). Trends and mechanisms of corruption in South Korea. The Pacific Review, 29(4), 625-645.

[5]. Kim, H. (2021). S Korea presidential poll: Choosing the lesser of two evils. Elections | Al Jazeera. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2021/12/22/sk-presidential-election-choosing-the-lesser-of-the-two-evils

[6]. You, K. H., Lee, I., & Park, A. (2016). Access to Government Information in South Korea: The Rise of Transparency as an Open Society Principle. J. Int’l Media & Ent. L., 7, 179.

[7]. Hahn, B. H. (1973). Factions and the Structure of Political Competition in Contemporary Korea: Some Preliminary Observations. Global Economic Review, 1(1), 59-75.

[8]. Ko, K. (2016). Historical review of anti-corruption policy in Korea: progress and challenges. Understanding Korean Public Administration, 240-259.

[9]. Min, K. S. (2019). The effectiveness of anti-corruption policies: measuring the impact of anti-corruption policies on integrity in the public organizations of South Korea. Crime, Law and Social Change, 71(2), 217-239.

[10]. ACRC. (2023). ACRC: Taking a Big Stride Forward on Transparency & Civil Rights. United Nation Development Program (UNDP). Retrieved from https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/seoul_policy_center/d322267f349e7d876cea6f448e734bd36f569cb9846f1d7a3bb207c2203965f1.pdf

[11]. Kalinowski, T., & Kim, S. (2014). Corruption and Anti-Corruption Policies in Korea. Hertie School of Governance (Conference Paper). Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/8314235/Corruption_and_Anti_Corruption_Policies_in_Korea

[12]. Lee, J., & Lee, A. (2016). Introduction to Korea’s Anti-Corruption initiative assessment. United Nation Development Program (UNDP). Retrieved from http://www.undp.org/content/seoul_policy_center/en/home/library/featured-publications/ACRC.html.

[13]. ACRC. (2021). 2021 ACRC Korea Annual Report. Anti-Corruption & Civil Rights Commission (ACRC). Retrieved from https://acrc.go.kr/board.es?mid=a20302000000&bid=64&act=view&list_no=39554

[14]. Kim, C., & Lee, A. (2018). Introduction to Korea’s Corruption Risk Assessment: A Tool to Analyze and Reduce Corruption Risks in Bills, Laws and Regulations. United Nation Development Program (UNDP). Retrieved from https://www.undp.org/policy-centre/seoul/publications/introduction-koreas-corruption-risk-assessment-tool-analyze-and-reduce-corruption-risks-bills-laws-and-regulations

[15]. Schultz, D., & Harutyunyan, K. (2015). Combating corruption: The development of whistleblowing laws in the United States, Europe, and Armenia. International Comparative Jurisprudence, 1(2), 87-97.

[16]. Transparency International. (n.d.). Corruption Perceptions Index. Retrieved from https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2022.

[17]. FAIS. (2018). Regulatory Transformation in the Republic of Korea Case Studies on Reform Implementation Experience. The World Bank Group. Retrieved from http://regulatoryreform.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/REGULATORY_TRANSFORMATION_IN_THE_REPUBLIC_OF_SOUTH_KOREA1.pdf

[18]. Hyung-ju, O. (2016). Little help offered on anti-graft act. The Korea Herald: Social Affairs. Retrieved from http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20161011000804&cpv=1

[19]. Corruption Risk Forecast. (n.d.). Index of Public Integrity. Retrieved from https://corruptionrisk.org/integrity/

[20]. The Economist. (2018). Cases against two ex-presidents of South Korea fit an alarming pattern. The Economist: Asia. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/asia/2018/04/07/cases-against-two-ex-presidents-of-south-korea-fit-an-alarming-pattern

[21]. TRACE International. (n.d.). TRACE Bribery Risk Matrix | View Country Risk Scores. Retrieved from https://www.traceinternational.org/trace-matrix

[22]. International Budget Partnership. (n.d.). Open Budget Survey 2021. Retrieved from https://internationalbudget.org/open-budget-survey-2021/

[23]. Nielsen, I. (2022). Public Perceptions of Corruption in East Asia: A Comparative Study of Japan, Singapore, and South Korea. Scholarly Horizons: University of Minnesota, Morris Undergraduate Journal, 9(1), 4.

[24]. OECD. (n.d.). Understanding the Drivers of Trust in Government Institutions in Korea. OECD Publishing Paris, Retreived from https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/9789264308992-5-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/9789264308992-5-en

[25]. Mo, P. H. (2001). Corruption and economic growth. Journal of Comparative Economics, 29(1), 66–79.

[26]. Pellegrini, L., & Gerlagh, R. (2004). Corruption’s effect on growth and its transmission channels. Kyklos, 57(3), 429–456.

[27]. Göbel, C. (2013). Warriors unchained: critical junctures and anticorruption in Taiwan and South Korea. Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft, 7(1), 219-242.

[28]. Van der Wal, Z. (2021). Singapore’s Corrupt Practices Investigations Bureau: Guardian of Public Integrity. Guardians of Public Value: How Public Organisations Become and Remain Institutions, 63-86.

[29]. Quah, J. S. (2007). Anti-corruption agencies in four Asian countries: a comparative analysis. International Public Management Review, 8(2), 73-96.

[30]. Khoo Wei Quan, W (2022). Integrity and Independence of Public and Law Enforcement Officials in Singapore. Publication: United Nations and Far East Institute. Retrieved from https://www.unafei.or.jp/publications/pdf/GG14/22_GG14_CP12_Singapore.pdf

[31]. Wing-Chi, H. (2013). Combating corruption: the Hong Kong experience. Tsinghua China L. Rev., 6, 239.

Cite this article

Li,C. (2023). Addressing Public Interest Violation Through Independent Anti-Corruption Bodies -A Case Study of the Anti-Corruption and Civil Rights Commission in South Korea. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,21,42-51.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the International Conference on Global Politics and Socio-Humanities

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Jain, A. K. (2001). Corruption: A review. Journal of economic surveys, 15(1), 71-121.

[2]. Min, K. S. (2023). The impact of corruption on government performance: evidence from South Korea. Crime, Law and Social Change, 79(3), 319-345.

[3]. Philp, M. (1997). Defining political corruption. Political Studies, 45(3), 436-462.

[4]. Kalinowski, T. (2016). Trends and mechanisms of corruption in South Korea. The Pacific Review, 29(4), 625-645.

[5]. Kim, H. (2021). S Korea presidential poll: Choosing the lesser of two evils. Elections | Al Jazeera. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2021/12/22/sk-presidential-election-choosing-the-lesser-of-the-two-evils

[6]. You, K. H., Lee, I., & Park, A. (2016). Access to Government Information in South Korea: The Rise of Transparency as an Open Society Principle. J. Int’l Media & Ent. L., 7, 179.

[7]. Hahn, B. H. (1973). Factions and the Structure of Political Competition in Contemporary Korea: Some Preliminary Observations. Global Economic Review, 1(1), 59-75.

[8]. Ko, K. (2016). Historical review of anti-corruption policy in Korea: progress and challenges. Understanding Korean Public Administration, 240-259.

[9]. Min, K. S. (2019). The effectiveness of anti-corruption policies: measuring the impact of anti-corruption policies on integrity in the public organizations of South Korea. Crime, Law and Social Change, 71(2), 217-239.

[10]. ACRC. (2023). ACRC: Taking a Big Stride Forward on Transparency & Civil Rights. United Nation Development Program (UNDP). Retrieved from https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/seoul_policy_center/d322267f349e7d876cea6f448e734bd36f569cb9846f1d7a3bb207c2203965f1.pdf

[11]. Kalinowski, T., & Kim, S. (2014). Corruption and Anti-Corruption Policies in Korea. Hertie School of Governance (Conference Paper). Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/8314235/Corruption_and_Anti_Corruption_Policies_in_Korea

[12]. Lee, J., & Lee, A. (2016). Introduction to Korea’s Anti-Corruption initiative assessment. United Nation Development Program (UNDP). Retrieved from http://www.undp.org/content/seoul_policy_center/en/home/library/featured-publications/ACRC.html.

[13]. ACRC. (2021). 2021 ACRC Korea Annual Report. Anti-Corruption & Civil Rights Commission (ACRC). Retrieved from https://acrc.go.kr/board.es?mid=a20302000000&bid=64&act=view&list_no=39554

[14]. Kim, C., & Lee, A. (2018). Introduction to Korea’s Corruption Risk Assessment: A Tool to Analyze and Reduce Corruption Risks in Bills, Laws and Regulations. United Nation Development Program (UNDP). Retrieved from https://www.undp.org/policy-centre/seoul/publications/introduction-koreas-corruption-risk-assessment-tool-analyze-and-reduce-corruption-risks-bills-laws-and-regulations

[15]. Schultz, D., & Harutyunyan, K. (2015). Combating corruption: The development of whistleblowing laws in the United States, Europe, and Armenia. International Comparative Jurisprudence, 1(2), 87-97.

[16]. Transparency International. (n.d.). Corruption Perceptions Index. Retrieved from https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2022.

[17]. FAIS. (2018). Regulatory Transformation in the Republic of Korea Case Studies on Reform Implementation Experience. The World Bank Group. Retrieved from http://regulatoryreform.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/REGULATORY_TRANSFORMATION_IN_THE_REPUBLIC_OF_SOUTH_KOREA1.pdf

[18]. Hyung-ju, O. (2016). Little help offered on anti-graft act. The Korea Herald: Social Affairs. Retrieved from http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20161011000804&cpv=1

[19]. Corruption Risk Forecast. (n.d.). Index of Public Integrity. Retrieved from https://corruptionrisk.org/integrity/

[20]. The Economist. (2018). Cases against two ex-presidents of South Korea fit an alarming pattern. The Economist: Asia. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/asia/2018/04/07/cases-against-two-ex-presidents-of-south-korea-fit-an-alarming-pattern

[21]. TRACE International. (n.d.). TRACE Bribery Risk Matrix | View Country Risk Scores. Retrieved from https://www.traceinternational.org/trace-matrix

[22]. International Budget Partnership. (n.d.). Open Budget Survey 2021. Retrieved from https://internationalbudget.org/open-budget-survey-2021/

[23]. Nielsen, I. (2022). Public Perceptions of Corruption in East Asia: A Comparative Study of Japan, Singapore, and South Korea. Scholarly Horizons: University of Minnesota, Morris Undergraduate Journal, 9(1), 4.

[24]. OECD. (n.d.). Understanding the Drivers of Trust in Government Institutions in Korea. OECD Publishing Paris, Retreived from https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/9789264308992-5-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/9789264308992-5-en

[25]. Mo, P. H. (2001). Corruption and economic growth. Journal of Comparative Economics, 29(1), 66–79.

[26]. Pellegrini, L., & Gerlagh, R. (2004). Corruption’s effect on growth and its transmission channels. Kyklos, 57(3), 429–456.

[27]. Göbel, C. (2013). Warriors unchained: critical junctures and anticorruption in Taiwan and South Korea. Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft, 7(1), 219-242.

[28]. Van der Wal, Z. (2021). Singapore’s Corrupt Practices Investigations Bureau: Guardian of Public Integrity. Guardians of Public Value: How Public Organisations Become and Remain Institutions, 63-86.

[29]. Quah, J. S. (2007). Anti-corruption agencies in four Asian countries: a comparative analysis. International Public Management Review, 8(2), 73-96.

[30]. Khoo Wei Quan, W (2022). Integrity and Independence of Public and Law Enforcement Officials in Singapore. Publication: United Nations and Far East Institute. Retrieved from https://www.unafei.or.jp/publications/pdf/GG14/22_GG14_CP12_Singapore.pdf

[31]. Wing-Chi, H. (2013). Combating corruption: the Hong Kong experience. Tsinghua China L. Rev., 6, 239.