1. Introduction

Nowadays, it is alarming that the effectiveness of antibiotics is compromising by the rapid emergence of drug resistance, which asks for new alternatives in antibacterial treatments [1]. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) derived from natural organisms have been found to demonstrate robust antimicrobial activity [2]. Moreover, high selectivity and affinity make AMPs tough to resistance, which gift AMPs promise as potential drugs for microbial infections, especially bacterial infections [3]. Unfortunately, not all natural AMPs can be developed into drugs successfully, many of them have failed in clinical trials due to their disadvantages in structure and activity such as stability issues [4] and considerable toxicity towards the human body [5]. To address these issues, optimization and new generation of AMPs is imperative.

While traditional experimental methods usually consume too much time and money, computer-aided drug design (CADD) is becoming a trend in medicinal chemistry and drug design [6]. With economic and effective outcome, multiple CADD methods are also employed to peptide design, including machine learning, de novo computational design, linguistic model and genetic algorithms [7]. Above these methods, quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSAR) modeling is prominent in AMPs design, which can not only identify different functions of potential peptide sequences, but also can predict peptide antimicrobial activity and toxicity for comprehensive drug research [8].

Through machine learning, QSAR models are capable of analysing a wide range of AMPs database to establish correlations between structure and activity, so that scientists can utilize these QSAR models to forecast and select new AMP sequences with heightened antimicrobial activity and improved functions [9]. 2D-QSAR models elucidate the structure-activity relationships based on attributes like hydrophobicity and electronic effects [10]. In contrast, 3D-QSAR models hinge on force fields concerning steric effects, electrostatic effects, hydrogen bond effects and so on [11]. Noteworthy, this work collects and analyses successful QSAR-guided AMPs designs, which exemplifies the tangible outcomes of peptide optimization that encompasses enhanced antimicrobial activity, expanded antimicrobial spectrum, reduced toxicity, and strengthen enzymatic resilience –– collectively enriching the landscape of antimicrobial drug design.

2. 2D-QSAR

Descriptors, which are explored by scientists to represent different levels of chemical structure ranging from 1D to 4D and higher, are the core factors in QSAR modelling [12]. Among these descriptors, 2D descriptors for QSAR modeling are well developed and they are frequently used in the prediction of compounds bioactivity, while 3D and higher QSAR models are still evolving [8].

In 2D-QSAR modeling, molecular topological and physicochemical properties are initially reflected by descriptors. Through statistic methods, such descriptors are related to regression equation like linear regression or partial least squares (PLS) regression. For example, Hansch analysis (Equation Ⅰ), the most classic model in 2D-QSAR, is designed by Crown Hansch based on a series of compound features and biological activity database [13]. Furthermore, multiple researches have confirmed the notable capacity of Hansch analysis in predicting quantitative structure-activity relationships of small molecules for drug design and toxicity prediction [14].

\( log\frac{1}{C}=-{k_{1}}{π^{2}}+{k_{2}}π+{k_{3}}σ+{k_{4}}{E_{s}}+{k_{s}} (Ι) \)

2.1. Case study-Dadapin-1 to -8

Owing to the cytotoxicity to human cells, though natural AMPs are considered to have low tendency to elicit resistance, they are interfered to be used as drugs [15]. As AMPs can kill the microbes, they inevitably have toxicity to human cells, so it is a challenge to balance antimicrobial potency and cytotoxicity effect, and one solution is to make progress in the selectivity of AMPs.

Mutator is a free software (http://split4.pmfst.hr/mutator/) that uses QSAR methods to provide contents of limited residue variation to improve the selectivity of peptides. Therefore, a study [15] firstly modified the algorithm of Mutator allowing it to screen multiple sequences simultaneously, then researchers screened the peptide sequence library and mutated peptides. According to Table 1, the satisfying selectivity results of optimized Dadapin peptides were chosen for later research and synthesis.

Focused on designing AMPs targeting Gram-negative bacteria, this study tested the antibacterial activity of Dadapin-1 to -8, and the results were moderate, whereas Dadapin-1 showed the best potency with an MIC value of 8 μM for most bacteria. It should be pointed that Dadapin-1 to -8 were discovered to behave really low toxicity for red blood cells, while Dadapin-1 and -8 were estimated almost non-toxic in HC50 values of ~700 μM and >1000 μM. Furthermore, according to the results of flow cytometry and atomic force microscopy (AFM), Dadapin-1 to -8 demonstrated great improvement in selectivity for specially killing bacteria by destroying their membranes without attacking the host cells.

Table 1. Mutation of Dadapin peptides sequences and their physico-chemical results [15].

Peptide | Mutationa | Sequence | Charge | H | μH | SI |

Dadapin-1 | SM (V8→K) | GLLRASSKWGRKYYVDLAGCAKA | +5 | -1.42 (-0.04) | 0.42 | 88.7 |

Dadapin-2 | DM (V8→K, A21→L) | GLLRASSKWGRKYYVDLAGCLKA | +5 | -0.95 (-0.03) | 0.46 | 94.8 |

Dadapin-3 | SM (V8→K) | GLFGKSSKWGRKYYVDLAGCAKA | +5 | -1.46 (0) | 0.39 | 86.8 |

Dadapin-4 | DHM (F3→S, R11→V) | GLSGKSSVWGVKYYVDLAGCAKA | +3 | -0.86 (0.21) | 0.18 | 89.9 |

Dadapin-5 | DM (G4→K, W9→Q) | GLFKKSSVQGRKYYVDLAGCAKA | +5 | -1.86 (-0.05) | 0.32 | 94.6 |

Dadapin-6 | DHM (A7→K, R18→L) | FLPKLFKKITKKNMAHIL | +6 | 0.31 (0.05) | 0.38 | 94.9 |

Dadapin-7 | DM (A7→Q, R18→L) | FLPKLFQKITKKNMAHIL | +5 | 0.53 (0.09) | 0.37 | 94.9 |

Dadapin-8 | DM (L3→K, K9→V) | AAKKGCWTVSIPPKPCF-NH2 | +4 | -0.89 (0.14) | 0.04 | 93.7 |

(a) SM means a single mutator of amino acids on the peptide sequence, DM means the double mutator, and DHM means double harsh mutator.

2.2. Case study-P4C2: an initiator of AgNP

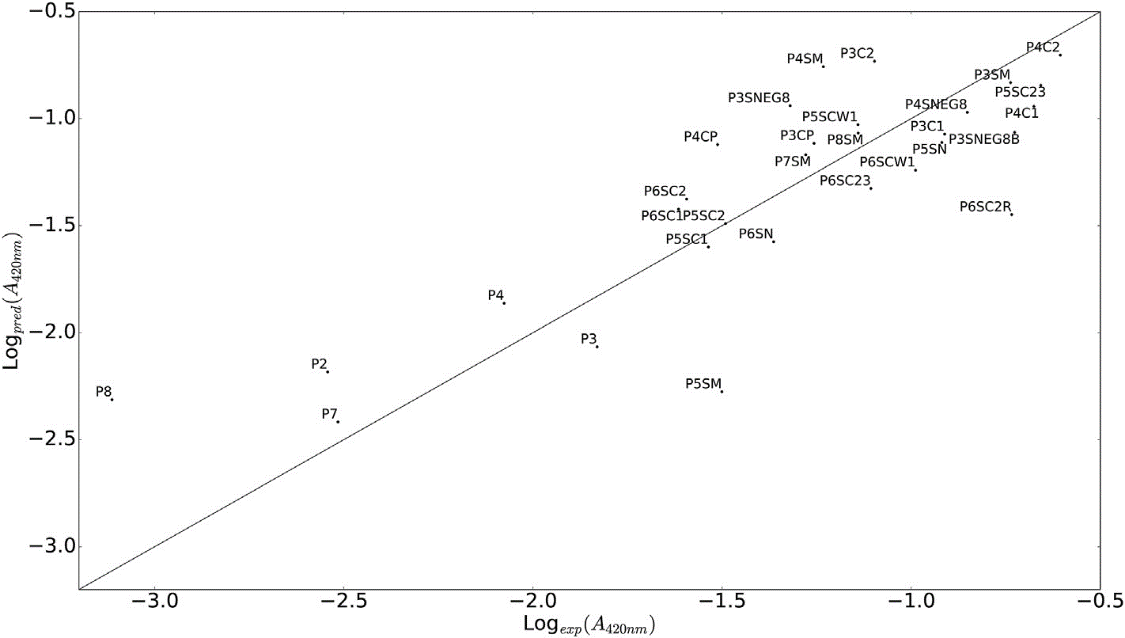

Antimicrobial silver nanoparticles (AgNP) are prevalence in antimicrobial agents because of the potent antimicrobial activity [16], and scientists have found that some peptides with a specific sequence can induce the formation of AgNP by reducing silver ions [17]. In order to identify the potential sequence for peptide optimization, computer software was aided to calculate the peptide descriptors from sequence (PEDES), and an PLS model was applied to analyze the reduction ability of peptides [16].

Figure 1. AgNP formation propensity predicted by QSAR model versus experiment results. R2 = 0.69 [16].`

According to this QSAR model, glutamic acid and glutamine were discovered to have a critical function in reducing the silver ions into AgNP. Positively charged silver ions are prone to coordinate with nucleophilic carboxylic group on the glutamic acid, so the concentration of silver ions was increased. Also, some studies suggested that this complexation decreased the activation barrier for silver reduction. After all, these conditions were favored for AgNP formation, which inspired researchers to finally design the P4C2 with improved antimicrobial activity against Escherichia coli (see Figure 1). Actually, the way P4C2 inducing AgNP formation was tested to be effectively and environmentally friendly, and it was also evaluated to have limited toxicity for mammalian cells, which promoted the further research.

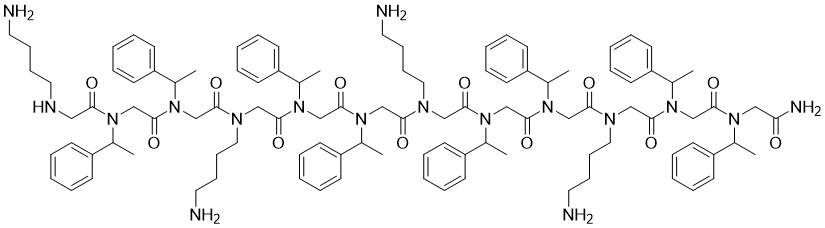

2.3. Case study-Peptoid-1: a mimic of AMP

Derivated from AMPs, AMP mimics are even harder to be degraded by enzymes [18]. In this regard, scientists eagerly build QSAR models for peptoid to explore potential treatments [19]. A study [20] applied 27 variable peptoid sequences to develop a new QSAR model, and this model was validated to accurately relate peptoid structure with antimicrobial activity. Quite similar approaches of AMPs design, they took advantages of this model to design peptoid-1 (see Figure 2), which was proved to have significant antimicrobial ability against Staphylococcus aureus certifying the promising future of applying peptoids as effective antimicrobial agents.

Figure 2. Chemical structure of peptoid-1.

Obviously, 2D-QSAR models have advantages in screening a large number of compounds with high computational speed and identifying potential structures with biological activity easily [10]. However, distinguished in screening and optimizing large-scale molecules, 2D-QSAR models still have deficiency in the concept of molecular spatial features, which limits their prediction and requires the supplement of 3D-QSAR models [21].

3. 3D-QSAR

3D-QSAR models have been replenished with the three-dimensional structures of molecules compared with traditional QSAR models, which give support for more complex biological activity prediction and accelerate the design of new AMPs [22]. Comparative molecular field analysis (CoMFA) and comparative molecular similarity index analysis (CoMSIA) are two prevailing 3D-QSAR models [23].

In CoMFA model, molecules will be analysed in two aspects of steric field (S) and electrostatic filed (E), and it draws a contour map to display, on the molecular structure, where bulky groups are favorable and where negative or positive charge is favorable [24]. Taking account into these messages, scientists are able to optimize peptide structure by substituting groups or amino acids on the sequence. Dissimilarly, CoMSIA not only considers the relationships of molecular structure connected with bioactivity, but also analyses similarities among molecules, so this model views more force fields than CoMFA, including steric field (S), electrostatic field (E), hydrophobic field (H), hydrogen bond acceptor field (A) and hydrogen bond donor field (D) [25].

3.1. Case study-oligopeptides

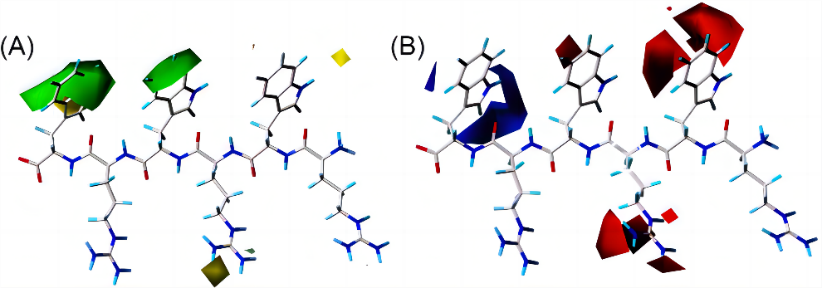

At present, Scientists are studying interpretability of QSAR models and facilitating multitask modeling to enhance the stability and predictability of models [8]. A study [26] had combined CoMFA and CoMSIA models in the design of new antimicrobial oligopeptides against S. aureus and E. coli. Both of the two models provided them with different structure details and activity variation that extensively enriched their perspectives on the peptide optimization.

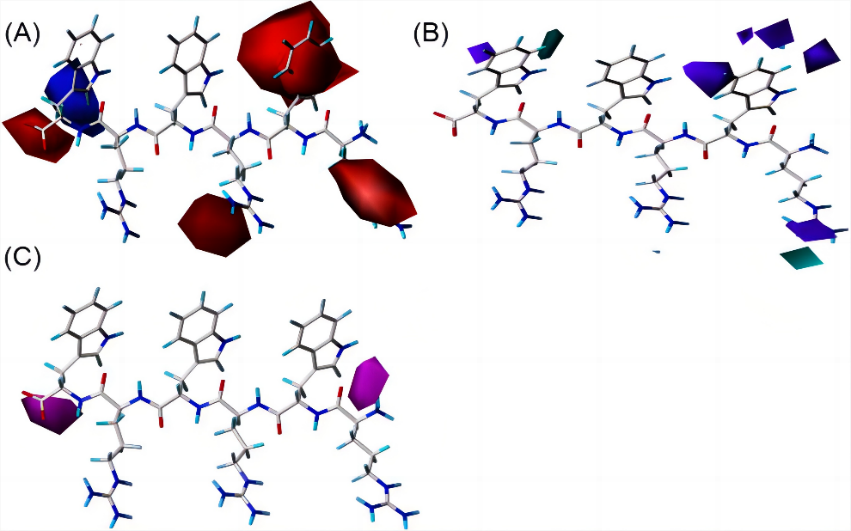

Figure 3. Contour maps of CoMFA. (A) In the steric field, bulky groups are favored in green contours, and yellow contours mean the bulky groups are not favored. (B) In electrostatic field, negative charge is favored in red contours but not favored in blue contours [26].

Figure 4. Contour maps of CoMSIA. (A) Electrostatic field. (B) In donor field, hydrogen bond donors are favored in light blue contours, and purple contours mean the opposite. (C) In acceptor field, hydrogen bond donors are not favored in the light purple contours [26].

To illustrate, Figure 3 are the contour maps of the peptide against E. coli provided by CoMFA, which indicated that antibacterial activity could be enhanced if the 4- and 6-places of peptide could be bulkier and 6-place was preferred to be positively charged. Consequently, peptide 18 with negatively charged amino acid aspartic (D) on the 6-place was disadvantaged, on the contrary, at 6-place of peptide 24, amino acid tryptophan (W) which was positively charged and bulkier than D, was expected to influence the peptide with a higher bioactivity. Likewise, contour maps of CoMSIA (see Figure 4) indicated where hydrogen bond donors and acceptors were favorable. Guided by these instructions, researchers synthesized 7 novel small AMPs with increased antibacterial activity and reduced host toxicity.

3.2. Case study-IDR-3002

Biofilm is a microbial polymer consisting of numerous bacteria and other kinds of microbes [27]. Secretion of these microbes makes biofilm viscous and easily to attach on the surface of solidity or liquid, hence, scientists have discovered that biofilm accounts for nearly 65% of all infections, which meanwhile have a close connection with chronic infections in human body [28]. Moreover, the surprising resistance of biofilm to traditional antibiotics is as 10 to 1000 times as normal bacteria [29].

So far, there has been no antibiofilm drug approved for clinical use, but there is an research [30] that has developed a 3D-QSAR model which achieves the prediction of relationships between antibiofilm activity and peptides. This QSAR model was validated to have as much as 85% precision, thus assisting to design the antibiofilm peptide IDR-3002, which was derived from IDR-1018 but owned 8-folds antibiofilm potency in vitro and was proved to be effective in vivo, offering a great opportunity for further antibiofilm drug design.

4. Other QSAR modeling approachES ANTIMICROBIAL PEPTIDES design

Although 2D- and 3D-QSAR models are regarded as prevalent and reliable tools in bioactivity prediction for drug design, challenges in selection of appropriate descriptors to build these QSAR models still remain perplexing [8]. For instance, the use of noninterpretable descriptors or use of excessive numbers of descriptors in a QSAR model can lead to model ineffectiveness and even errors. Notwithstanding, performing the three-dimensional structure by 3D-QSAR model sometimes is restricted in complex computer resources and operation. Concerned about these difficulties, instead of utilizing 2D and 3D QSAR modeling, some scientists prefer to take advantages of other methods to build new QSAR models in their researches.

In the study of Mastoparan-analogs [31], to build a new model, researchers modified a typical QSAR paradigm, from Endpoint = Function (system of atoms) to Endpoint = Function (sequence of amino acids), which became more suitable for analysis of amino acids in peptide and protein. Along with the help of software CORAL (http://www.insilico.eu/coral), they selected the optimal descriptors for QSAR modeling. Afterwards, Monte Carlo method was applied for the calculation of antibacterial activity in the model [32]. Thoughtfully, the study also compared the results provided by different QSAR models, demonstrating the new QSAR model with calculation of Monte Carlo method made the more accurate prediction than 2D-QSAR model and 3D-QSAR model, which implies that though 2D- and 3D-QSAR models are widely used in peptides design, but commonly usefulness does not necessarily equal to the best answer, as authentic research demands to implement specific QSAR models that match the research.

5. Conclusion

High affinity and selectivity properties of AMPs have attracted scientists to study the replacements for traditional antibiotics and overcome the bacterial resistance dilemma. Incorporation of mathematic techniques and computational calculation, QSAR modeling is evidently efficient and pivotal in AMPs design. This overview summarizes successful AMPs deign aided by QSAR models in recent 10 years. Except for bioactivity prediction, current trends in QSAR modeling aided drug design also involve chemical data curation, toxicity prediction, metabolism prediction and experimental validation. Additionally, there are still some challenges in QSAR modeling, such as ignorance of data heterogeneity, descriptors selection which need further research to perfect and explain. In summary, we have already witness the QSAR models contributing to different AMPs design, and we are expecting this method to thrive and continuously make contributions to human health.

References

[1]. Roca, I.; Akova, M.; Baquero, F.; Carlet, J.; Cavaleri, M.; Coenen, S.; Cohen, J.; Findlay, D.; Gyssens, I.; Heure, O. E.; Kahlmeter, G.; Kruse, H.; Laxminarayan, R.; Liébana, E.; López-Cerero, L.; MacGowan, A.; Martins, M.; Rodríguez-Baño, J.; Rolain, J.-M.; Segovia, C.; Sigauque, B.; Tacconelli, E.; Wellington, E.; Vila, J. The Global Threat of Antimicrobial Resistance: Science for Intervention. New Microbes and New Infections 2015, 6, 22–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmni.2015.02.007.

[2]. Brogden, K. A. Antimicrobial Peptides: Pore Formers or Metabolic Inhibitors in Bacteria? Nat Rev Microbiol 2005, 3 (3), 238–250. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro1098.

[3]. Dathe, M.; Schümann, M.; Wieprecht, T.; Winkler, A.; Beyermann, M.; Krause, E.; Matsuzaki, K.; Murase, O.; Bienert, M. Peptide Helicity and Membrane Surface Charge Modulate the Balance of Electrostatic and Hydrophobic Interactions with Lipid Bilayers and Biological Membranes. Biochemistry 1996, 35 (38), 12612–12622. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi960835f.

[4]. Zhao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Qiu, S.; Wang, J.; Peng, J.; Zhao, P.; Zhu, R.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, K.; Yan, W.; Wang, R. Antimicrobial Activity and Stability of the D-Amino Acid Substituted Derivatives of Antimicrobial Peptide Polybia-MPI. AMB Express 2016, 6 (1), 122. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-016-0295-8.

[5]. Oshiro, K. G. N.; Cândido, E. S.; Chan, L. Y.; Torres, M. D. T.; Monges, B. E. D.; Rodrigues, S. G.; Porto, W. F.; Ribeiro, S. M.; Henriques, S. T.; Lu, T. K.; de la Fuente-Nunez, C.; Craik, D. J.; Franco, O. L.; Cardoso, M. H. Computer-Aided Design of Mastoparan-like Peptides Enables the Generation of Nontoxic Variants with Extended Antibacterial Properties. J Med Chem 2019, 62 (17), 8140–8151. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00915.

[6]. Sabe, V. T.; Ntombela, T.; Jhamba, L. A.; Maguire, G. E. M.; Govender, T.; Naicker, T.; Kruger, H. G. Current Trends in Computer Aided Drug Design and a Highlight of Drugs Discovered via Computational Techniques: A Review. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2021, 224, 113705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113705.

[7]. Cardoso, M. H.; Orozco, R. Q.; Rezende, S. B.; Rodrigues, G.; Oshiro, K. G. N.; Cândido, E. S.; Franco, O. L. Computer-Aided Design of Antimicrobial Peptides: Are We Generating Effective Drug Candidates? Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 10.

[8]. Cherkasov, A.; Muratov, E. N.; Fourches, D.; Varnek, A.; Baskin, I. I.; Cronin, M.; Dearden, J.; Gramatica, P.; Martin, Y. C.; Todeschini, R.; Consonni, V.; Kuz’min, V. E.; Cramer, R.; Benigni, R.; Yang, C.; Rathman, J.; Terfloth, L.; Gasteiger, J.; Richard, A.; Tropsha, A. QSAR Modeling: Where Have You Been? Where Are You Going To? J Med Chem 2014, 57 (12), 4977–5010. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm4004285.

[9]. Hilpert, K.; Fjell, C. D.; Cherkasov, A. Short Linear Cationic Antimicrobial Peptides: Screening, Optimizing, and Prediction. Methods Mol Biol 2008, 494, 127–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-59745-419-3_8.

[10]. Roy, K.; Das, R. N. A Review on Principles, Theory and Practices of 2D-QSAR. Curr Drug Metab 2014, 15 (4), 346–379. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389200215666140908102230.

[11]. Verma, J.; Khedkar, V. M.; Coutinho, E. C. 3D-QSAR in Drug Design--a Review. Curr Top Med Chem 2010, 10 (1), 95–115. https://doi.org/10.2174/156802610790232260.

[12]. Xue, L.; Bajorath, J. Molecular Descriptors in Chemoinformatics, Computational Combinatorial Chemistry, and Virtual Screening. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen 2000, 3 (5), 363–372. https://doi.org/10.2174/1386207003331454.

[13]. Hansch, C. Quantitative Approach to Biochemical Structure-Activity Relationships. Acc. Chem. Res. 1969, 2 (8), 232–239. https://doi.org/10.1021/ar50020a002.

[14]. Debnath, A. K. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Paradigm--Hansch Era to New Millennium. Mini Rev Med Chem 2001, 1 (2), 187–195. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389557013407061.

[15]. Rončević, T.; Vukičević, D.; Krce, L.; Benincasa, M.; Aviani, I.; Maravić, A.; Tossi, A. Selection and Redesign for High Selectivity of Membrane-Active Antimicrobial Peptides from a Dedicated Sequence/Function Database. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 2019, 1861 (4), 827–834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamem.2019.01.017.

[16]. Božič Abram, S.; Aupič, J.; Dražić, G.; Gradišar, H.; Jerala, R. Coiled-Coil Forming Peptides for the Induction of Silver Nanoparticles. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2016, 472 (3), 566–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.03.042.

[17]. Dickerson, M. B.; Sandhage, K. H.; Naik, R. R. Protein- and Peptide-Directed Syntheses of Inorganic Materials. Chem Rev 2008, 108 (11), 4935–4978. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr8002328.

[18]. Chongsiriwatana, N. P.; Patch, J. A.; Czyzewski, A. M.; Dohm, M. T.; Ivankin, A.; Gidalevitz, D.; Zuckermann, R. N.; Barron, A. E. Peptoids That Mimic the Structure, Function, and Mechanism of Helical Antimicrobial Peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105 (8), 2794–2799. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0708254105.

[19]. Mojsoska, B.; Zuckermann, R. N.; Jenssen, H. Structure-Activity Relationship Study of Novel Peptoids That Mimic the Structure of Antimicrobial Peptides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015, 59 (7), 4112–4120. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00237-15.

[20]. Czyzewski, A. M.; Jenssen, H.; Fjell, C. D.; Waldbrook, M.; Chongsiriwatana, N. P.; Yuen, E.; Hancock, R. E. W.; Barron, A. E. In Vivo, In Vitro, and In Silico Characterization of Peptoids as Antimicrobial Agents. PLOS ONE 2016, 11 (2), e0135961. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135961.

[21]. Bahia, M. S.; Kaspi, O.; Touitou, M.; Binayev, I.; Dhail, S.; Spiegel, J.; Khazanov, N.; Yosipof, A.; Senderowitz, H. A Comparison between 2D and 3D Descriptors in QSAR Modeling Based on Bio-Active Conformations. Mol Inform 2023, 42 (4), e2200186. https://doi.org/10.1002/minf.202200186.

[22]. Liu, S.; Bao, J.; Lao, X.; Zheng, H. Novel 3D Structure Based Model for Activity Prediction and Design of Antimicrobial Peptides. Sci Rep 2018, 8 (1), 11189. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-29566-5.

[23]. B, B.; T, K.; A, L. Ligand-Based Computer-Aided Pesticide Design. A Review of Applications of the CoMFA and CoMSIA Methodologies. Pest management science 2003, 59 (4). https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.614.

[24]. Podlogar, B. L.; Ferguson, D. M. QSAR and CoMFA: A Perspective on the Practical Application to Drug Discovery. Drug Des Discov 2000, 17 (1), 4–12.

[25]. Wolohan, P.; Reichert, D. E. CoMSIA and Docking Study of Rhenium Based Estrogen Receptor Ligand Analogs. Steroids 2007, 72 (3), 247–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.steroids. 2006.11.011.

[26]. Li, G., Wang, Y., Shen, Y. et al. In silico design of antimicrobial oligopeptides based on 3D-QSAR modeling and bioassay evaluation. Med Chem Res 30, 2030–2041 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00044-021-02789-4

[27]. Yin, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; He, J. Biofilms: The Microbial “Protective Clothing” in Extreme Environments. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20 (14), 3423. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20143423.

[28]. de la Fuente-Núñez, C.; Reffuveille, F.; Fernández, L.; Hancock, R. E. W. Bacterial Biofilm Development as a Multicellular Adaptation: Antibiotic Resistance and New Therapeutic Strategies. Curr Opin Microbiol 2013, 16 (5), 580–589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mib. 2013.06.013.

[29]. Høiby, N.; Bjarnsholt, T.; Givskov, M.; Molin, S.; Ciofu, O. Antibiotic Resistance of Bacterial Biofilms. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2010, 35 (4), 322–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag. 2009.12.011.

[30]. Haney, E. F.; Brito-Sánchez, Y.; Trimble, M. J.; Mansour, S. C.; Cherkasov, A.; Hancock, R. E. W. Computer-Aided Discovery of Peptides That Specifically Attack Bacterial Biofilms. Sci Rep 2018, 8 (1), 1871. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-19669-4.

[31]. Toropova, M. A.; Veselinović, A. M.; Veselinović, J. B.; Stojanović, D. B.; Toropov, A. A. QSAR Modeling of the Antimicrobial Activity of Peptides as a Mathematical Function of a Sequence of Amino Acids. Computational Biology and Chemistry 2015, 59, 126–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2015.09.009.

[32]. Toropova, A. P.; Toropov, A. A. CORAL Software: Prediction of Carcinogenicity of Drugs by Means of the Monte Carlo Method. Eur J Pharm Sci 2014, 52, 21–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2013.10.005.

Cite this article

Shang,Z. (2024). Quantitative structure-activity relationships modelling in antimicrobial peptides design. Theoretical and Natural Science,44,94-101.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Modern Medicine and Global Health

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Roca, I.; Akova, M.; Baquero, F.; Carlet, J.; Cavaleri, M.; Coenen, S.; Cohen, J.; Findlay, D.; Gyssens, I.; Heure, O. E.; Kahlmeter, G.; Kruse, H.; Laxminarayan, R.; Liébana, E.; López-Cerero, L.; MacGowan, A.; Martins, M.; Rodríguez-Baño, J.; Rolain, J.-M.; Segovia, C.; Sigauque, B.; Tacconelli, E.; Wellington, E.; Vila, J. The Global Threat of Antimicrobial Resistance: Science for Intervention. New Microbes and New Infections 2015, 6, 22–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmni.2015.02.007.

[2]. Brogden, K. A. Antimicrobial Peptides: Pore Formers or Metabolic Inhibitors in Bacteria? Nat Rev Microbiol 2005, 3 (3), 238–250. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro1098.

[3]. Dathe, M.; Schümann, M.; Wieprecht, T.; Winkler, A.; Beyermann, M.; Krause, E.; Matsuzaki, K.; Murase, O.; Bienert, M. Peptide Helicity and Membrane Surface Charge Modulate the Balance of Electrostatic and Hydrophobic Interactions with Lipid Bilayers and Biological Membranes. Biochemistry 1996, 35 (38), 12612–12622. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi960835f.

[4]. Zhao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Qiu, S.; Wang, J.; Peng, J.; Zhao, P.; Zhu, R.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, K.; Yan, W.; Wang, R. Antimicrobial Activity and Stability of the D-Amino Acid Substituted Derivatives of Antimicrobial Peptide Polybia-MPI. AMB Express 2016, 6 (1), 122. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-016-0295-8.

[5]. Oshiro, K. G. N.; Cândido, E. S.; Chan, L. Y.; Torres, M. D. T.; Monges, B. E. D.; Rodrigues, S. G.; Porto, W. F.; Ribeiro, S. M.; Henriques, S. T.; Lu, T. K.; de la Fuente-Nunez, C.; Craik, D. J.; Franco, O. L.; Cardoso, M. H. Computer-Aided Design of Mastoparan-like Peptides Enables the Generation of Nontoxic Variants with Extended Antibacterial Properties. J Med Chem 2019, 62 (17), 8140–8151. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00915.

[6]. Sabe, V. T.; Ntombela, T.; Jhamba, L. A.; Maguire, G. E. M.; Govender, T.; Naicker, T.; Kruger, H. G. Current Trends in Computer Aided Drug Design and a Highlight of Drugs Discovered via Computational Techniques: A Review. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2021, 224, 113705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113705.

[7]. Cardoso, M. H.; Orozco, R. Q.; Rezende, S. B.; Rodrigues, G.; Oshiro, K. G. N.; Cândido, E. S.; Franco, O. L. Computer-Aided Design of Antimicrobial Peptides: Are We Generating Effective Drug Candidates? Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 10.

[8]. Cherkasov, A.; Muratov, E. N.; Fourches, D.; Varnek, A.; Baskin, I. I.; Cronin, M.; Dearden, J.; Gramatica, P.; Martin, Y. C.; Todeschini, R.; Consonni, V.; Kuz’min, V. E.; Cramer, R.; Benigni, R.; Yang, C.; Rathman, J.; Terfloth, L.; Gasteiger, J.; Richard, A.; Tropsha, A. QSAR Modeling: Where Have You Been? Where Are You Going To? J Med Chem 2014, 57 (12), 4977–5010. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm4004285.

[9]. Hilpert, K.; Fjell, C. D.; Cherkasov, A. Short Linear Cationic Antimicrobial Peptides: Screening, Optimizing, and Prediction. Methods Mol Biol 2008, 494, 127–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-59745-419-3_8.

[10]. Roy, K.; Das, R. N. A Review on Principles, Theory and Practices of 2D-QSAR. Curr Drug Metab 2014, 15 (4), 346–379. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389200215666140908102230.

[11]. Verma, J.; Khedkar, V. M.; Coutinho, E. C. 3D-QSAR in Drug Design--a Review. Curr Top Med Chem 2010, 10 (1), 95–115. https://doi.org/10.2174/156802610790232260.

[12]. Xue, L.; Bajorath, J. Molecular Descriptors in Chemoinformatics, Computational Combinatorial Chemistry, and Virtual Screening. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen 2000, 3 (5), 363–372. https://doi.org/10.2174/1386207003331454.

[13]. Hansch, C. Quantitative Approach to Biochemical Structure-Activity Relationships. Acc. Chem. Res. 1969, 2 (8), 232–239. https://doi.org/10.1021/ar50020a002.

[14]. Debnath, A. K. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Paradigm--Hansch Era to New Millennium. Mini Rev Med Chem 2001, 1 (2), 187–195. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389557013407061.

[15]. Rončević, T.; Vukičević, D.; Krce, L.; Benincasa, M.; Aviani, I.; Maravić, A.; Tossi, A. Selection and Redesign for High Selectivity of Membrane-Active Antimicrobial Peptides from a Dedicated Sequence/Function Database. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 2019, 1861 (4), 827–834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamem.2019.01.017.

[16]. Božič Abram, S.; Aupič, J.; Dražić, G.; Gradišar, H.; Jerala, R. Coiled-Coil Forming Peptides for the Induction of Silver Nanoparticles. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2016, 472 (3), 566–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.03.042.

[17]. Dickerson, M. B.; Sandhage, K. H.; Naik, R. R. Protein- and Peptide-Directed Syntheses of Inorganic Materials. Chem Rev 2008, 108 (11), 4935–4978. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr8002328.

[18]. Chongsiriwatana, N. P.; Patch, J. A.; Czyzewski, A. M.; Dohm, M. T.; Ivankin, A.; Gidalevitz, D.; Zuckermann, R. N.; Barron, A. E. Peptoids That Mimic the Structure, Function, and Mechanism of Helical Antimicrobial Peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105 (8), 2794–2799. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0708254105.

[19]. Mojsoska, B.; Zuckermann, R. N.; Jenssen, H. Structure-Activity Relationship Study of Novel Peptoids That Mimic the Structure of Antimicrobial Peptides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015, 59 (7), 4112–4120. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00237-15.

[20]. Czyzewski, A. M.; Jenssen, H.; Fjell, C. D.; Waldbrook, M.; Chongsiriwatana, N. P.; Yuen, E.; Hancock, R. E. W.; Barron, A. E. In Vivo, In Vitro, and In Silico Characterization of Peptoids as Antimicrobial Agents. PLOS ONE 2016, 11 (2), e0135961. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135961.

[21]. Bahia, M. S.; Kaspi, O.; Touitou, M.; Binayev, I.; Dhail, S.; Spiegel, J.; Khazanov, N.; Yosipof, A.; Senderowitz, H. A Comparison between 2D and 3D Descriptors in QSAR Modeling Based on Bio-Active Conformations. Mol Inform 2023, 42 (4), e2200186. https://doi.org/10.1002/minf.202200186.

[22]. Liu, S.; Bao, J.; Lao, X.; Zheng, H. Novel 3D Structure Based Model for Activity Prediction and Design of Antimicrobial Peptides. Sci Rep 2018, 8 (1), 11189. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-29566-5.

[23]. B, B.; T, K.; A, L. Ligand-Based Computer-Aided Pesticide Design. A Review of Applications of the CoMFA and CoMSIA Methodologies. Pest management science 2003, 59 (4). https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.614.

[24]. Podlogar, B. L.; Ferguson, D. M. QSAR and CoMFA: A Perspective on the Practical Application to Drug Discovery. Drug Des Discov 2000, 17 (1), 4–12.

[25]. Wolohan, P.; Reichert, D. E. CoMSIA and Docking Study of Rhenium Based Estrogen Receptor Ligand Analogs. Steroids 2007, 72 (3), 247–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.steroids. 2006.11.011.

[26]. Li, G., Wang, Y., Shen, Y. et al. In silico design of antimicrobial oligopeptides based on 3D-QSAR modeling and bioassay evaluation. Med Chem Res 30, 2030–2041 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00044-021-02789-4

[27]. Yin, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; He, J. Biofilms: The Microbial “Protective Clothing” in Extreme Environments. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20 (14), 3423. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20143423.

[28]. de la Fuente-Núñez, C.; Reffuveille, F.; Fernández, L.; Hancock, R. E. W. Bacterial Biofilm Development as a Multicellular Adaptation: Antibiotic Resistance and New Therapeutic Strategies. Curr Opin Microbiol 2013, 16 (5), 580–589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mib. 2013.06.013.

[29]. Høiby, N.; Bjarnsholt, T.; Givskov, M.; Molin, S.; Ciofu, O. Antibiotic Resistance of Bacterial Biofilms. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2010, 35 (4), 322–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag. 2009.12.011.

[30]. Haney, E. F.; Brito-Sánchez, Y.; Trimble, M. J.; Mansour, S. C.; Cherkasov, A.; Hancock, R. E. W. Computer-Aided Discovery of Peptides That Specifically Attack Bacterial Biofilms. Sci Rep 2018, 8 (1), 1871. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-19669-4.

[31]. Toropova, M. A.; Veselinović, A. M.; Veselinović, J. B.; Stojanović, D. B.; Toropov, A. A. QSAR Modeling of the Antimicrobial Activity of Peptides as a Mathematical Function of a Sequence of Amino Acids. Computational Biology and Chemistry 2015, 59, 126–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2015.09.009.

[32]. Toropova, A. P.; Toropov, A. A. CORAL Software: Prediction of Carcinogenicity of Drugs by Means of the Monte Carlo Method. Eur J Pharm Sci 2014, 52, 21–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2013.10.005.