1. Introduction

Tissue engineering is a transformative field that combines biology, engineering, and medicine to restore, maintain, or enhance tissue functions [1]. By leveraging the body’s natural ability to heal and grow tissues, tissue engineering offers innovative solutions to challenges like organ failure and severe injuries[2]. Central to this field is the use of biomaterials—engineered substances designed to interact with biological systems. These materials serve as scaffolds, providing structural support and influencing cellular behavior to promote tissue regeneration [3].

2. Hydrogels

2.1. Historical Background

The concept of tissue engineering emerged in the late 20th century, fueled by advances in biomaterials, cell biology, and regenerative medicine. In the early 1990s, significant progress was made with the development of scaffolds and bioreactors. These scaffolds, often made from biocompatible polymers or composites, mimic the extracellular matrix (ECM) and create a 3D environment conducive to cell growth and tissue formation. This period also saw the publication of Robert Langer and Joseph Vacanti's seminal 1993 paper "Tissue Engineering," which laid the groundwork for the field by emphasizing the importance of biomaterial selection.

By the early 2000s, the feasibility of tissue engineering was demonstrated through successful clinical applications. A notable example is Anthony Atala's work on tissue-engineered autologous bladders, reported in The Lancet in 2006. These constructs, which combined synthetic and natural biomaterials, provided a supportive framework for cell growth, leading to functional tissue regeneration in patients.

2.2. Materials, Properties, and Advantages

Biomaterials used in tissue engineering fall into two main categories: natural and synthetic.

2.3. Natural Biomaterials

Examples include collagen and gelatin, which closely resemble the native ECM. They are inherently biocompatible and bioactive, promoting cell adhesion and growth. However, their mechanical properties and degradation rates can be difficult to control, limiting their use in certain applications.

2.4. Synthetic Biomaterials

Examples include PLGA, PCL, and PEG. These materials offer greater control over mechanical strength, degradation rates, and structural properties. They can be engineered to meet specific tissue requirements and modified to include bioactive molecules that enhance cellular interactions.

The primary advantage of advanced biomaterials lies in their ability to support cell growth, guide tissue formation, and degrade in sync with tissue regeneration. They can also deliver therapeutic agents directly to the site of injury, further enhancing tissue repair. The ongoing development of novel biomaterials is crucial for overcoming current challenges in tissue engineering and achieving more reliable outcomes.

2.5. Comparison of Hydrogels and Other Types of Gels

Several kinds of gels are put into use today. The first one is hydrogel. These gels are three-dimensional networks of hydrophilic polymers that retain a significant amount of water because of hydrophilic groups like hydroxyl, carboxyl, and amide groups forming hydrogen bonds with water molecules. For instance, hydrogels in wound dressings absorb wound exudate and keep the wound moist to heal.

Talking about other gels, for example, the organic gels. These gels consist of phase trapped with a network of polymers or low molecular weight gelators, stabled by non-covalent connections like van der Waals forces or π-π stacking. An example would be organic gels used in cosmetics to improve the texture and application.

What’s more, there are xerogels, which are the kind of gels that are formed by drying a gel and result in a porous and solid structure. For example, xerogels in air purifiers can capture and store toxic and harmful gases, utilizing their high surface area and nature [4].

Talking about how those gels are created or produced, the hydrogels are typically fabricated by polymerizing or crosslinking monomers in an aqueous solution. For example, polyacrylamide hydrogels are synthesized through free-radical polymerization of acrylamide monomers, it is commonly used as a gel matrix in electrophoresis experiments.

On the other hand, organic gels are usually prepared by dissolving gelators in organic solvents, then cooling or solvent evaporation, allowing the gelators to assemble into a network by themselves. An example is some kind of food gel that can solidify after heating and cooling down.

When talking about xerogels, are gels that were created by forming hydrogels or organic gels and then drying them using supercritical or freeze-drying methods, which can also preserve the gel structure. An example is xerogels that is put into used as catalyst supports.

When comparing hydrogels to other gels, several factors caught our eye. They are known for their high water content and biocompatibility, which make them much more ideal for drug delivery and tissue engineering applications than the other gels. For example, injectable hydrogels can be used for controlled drug release [5]. And since hydrogels won't react with most of the medicines that are used in the therapy, makes it more stable in the bond reactions for long-term use in joint healing such as knee and elbows.

Furthermore, the mechanical properties of hydrogels also have a great advantage in tissue engineering. Hydrogels can be very soft and flexible, which holds a similar property compared with natural tissues that the human body produces, which is beneficial for soft tissue engineering. What’s more, it is also useful for athletes to use when having a joint or soft tissue injury because it has a stable structure and can control the delivery of drugs [6].

3. Tissue-engineered scaffold

Tissue-engineered scaffold is an important part of the application in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, which provides a place for cells to attach, grow and differentiate to form new tissues or organs.

3.1. Principle

The core principle of tissue engineering scaffolds is to enable cells to attach, grow, migrate and differentiate on them by providing a three-dimensional structure similar to the extracellular matrix (ECM) in vivo. The process typically involves the following detailed steps:

3.1.1. Cell isolation and culture [7]

Cell Separation: First, the cell type required for treatment is isolated from the organism. Using centrifugation, large cells are separated from small cells by centrifugation and dense cells are separated from light cells by centrifugation.

Cell culture: The isolated cells are cultured in a specific medium. The medium usually contains the necessary nutrients, growth factors and serum to support cell growth and proliferation.

3.1.2. Scaffold Construction

Designing the scaffold: Designing and constructing a suitable scaffold based on the structure and function of the tissue. This requires consideration of a variety of factors, such as the porosity, mechanical strength, biocompatibility and degradability of the scaffold. Porosity affects cell penetration and nutrient transport; mechanical strength needs to be matched to the tissue to provide adequate mechanical support; biocompatibility ensures that the scaffold material does not trigger an immune reaction with the host; and degradability ensures that the scaffold can be replaced by new tissue in vivo.

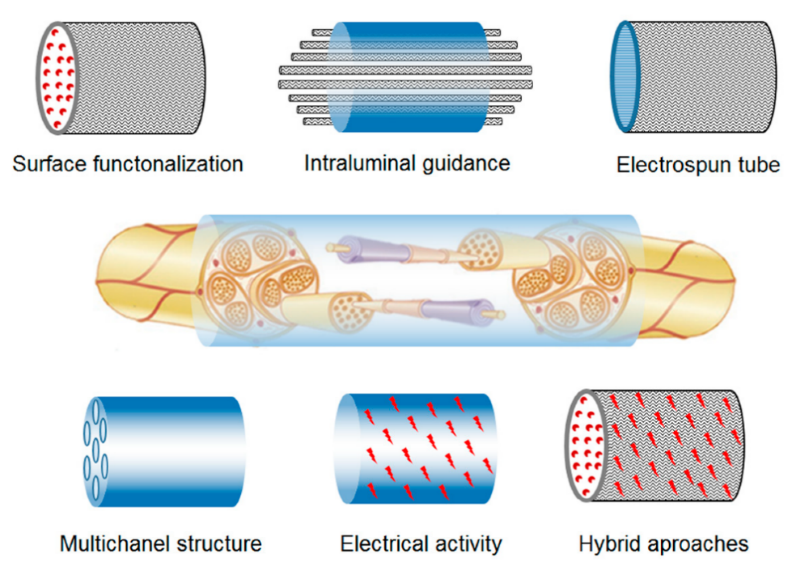

Manufacture of scaffolds: commonly used scaffold manufacturing techniques include 3D printing, electrospinning, etc. 3D printing allows precise control of scaffold geometry and internal pore distribution [8]; electrospinning can generate fibrous scaffolds that mimic the structure of the natural extracellular matrix [9]; as shown in Figure 1.

.

.

Figure 1. Electrospun scaffold approaches for nerve regeneration.

3.2. In vivo transplantation and tissue regeneration

In vivo transplantation: transplantation of a tissue-engineered scaffold into a defective part of the patient's body. This can be done by surgically implanting the composite directly into the defect site or by introducing it into the body through minimally invasive techniques. During the grafting process, it needs to be ensured that it integrates well with the surrounding tissue to facilitate the growth of new tissue and functional recovery.

3.3. Tissue regeneration

In vivo, the stent gradually degrades and is replaced by new tissue. The rate of degradation of the scaffold material needs to match the rate of tissue regeneration to ensure that the neoplastic tissue is able to fully populate and replace the scaffold before it degrades. Ultimately, the cells in the complex and the scaffold work together to achieve regeneration and functional recovery of the target tissue or organ.

3.4. Principles

3.4.1. Natural materials

Collagen [10]: Collagen is one of the main components of the extracellular matrix and plays a structural support role in many tissues. It is one of the main components of the extracellular matrix. It has good biocompatibility, so collagen scaffolds can promote cell attachment, proliferation and differentiation. It is biocompatible, so collagen scaffolds promote cell attachment, proliferation and differentiation. Moreover, collagen is degradable, so it can be gradually degraded by enzymes and replaced by new tissues in the body.

3.4.2. Synthetic Materials

Polylactic acid (PLA) [11]: PLA is a biodegradable polymer commonly used in bone tissue engineering scaffolds. PLA scaffolds have good mechanical strength and biocompatibility, and its degradation product is lactic acid, which can be metabolized and naturally excreted by the human body. The degradation rate of PLA scaffolds can be controlled by adjusting its molecular weight and crystallinity, which is suitable for bone tissue regeneration that requires longer support.

3.5. Comparison

3.5.1. Material selection

Traditional bioscaffolds usually use natural materials, such as bovine bone, pig skin, etc. Although these materials have a certain degree of biocompatibility, their mechanical properties and degradation rate are difficult to control. In contrast, tissue engineering scaffolds can be optimized in terms of biocompatibility, mechanical properties and degradation rate by selecting suitable natural materials, synthetic materials or composite materials according to specific needs.

3.5.2. Functional properties

Traditional bioscaffolds usually only provide mechanical support, while tissue-engineered scaffolds can not only provide mechanical support, but also promote cell attachment, proliferation and differentiation by adding growth factors and extracellular matrix proteins. In addition, the degradation rate of tissue-engineered scaffolds can be precisely controlled by adjusting the material composition and processing technology, so that they can be gradually degraded and replaced by new tissues in the process of tissue repair.

4. Kartogenin (KGN)

4.1. Mechanism of action of KGN

KGN is a small molecule compound which can promote the differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells.

KGN can promote the growth of cartilage by interrupting the combination of core binding factor β(CBFβ) and filamin A(FLNA). In the quiescent state, CBFβ is sequestered in the cytoplasm by binding to FLNA. When CBFβ is activated, it will dissociate from FLNA and bind with runt-related transcription factor 1(RUNX1) to form CBFβ-RNUX1 complex which can activate the transcription of proteins that involved in cartilage repairing and enhance the synthesis of cartilage matrix. The function of KGN is to bind with FLNA to block the binding of FLNA to CBFβ, which can increase the nuclear translocation of CBFβ and enhance the formation of CBFβ-RUNX1 complex, to help the growth of cartilage [12]. After the formation of CBFβ-RUNX1 complex, the synthesis of type 2 collagen (COL-2) and aggrecan, which are the mainly constituent of cartilage matrix, will be increased. In addition, KGN can inhibit the expression of degrading enzymes such as matrix metalloproteinase 13 (MMP13) and ADAMTS5 with thrombospondin domain which would degrade cartilage matrix and lead to cartilage degeneration. Also, KGN regulates the intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) level in chondrocytes stimulated by interleukin-1 Beta (IL-1β) by upregulating the nuclear Factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (NRF2). NRF2 plays a crucial role in maintaining the antioxidant balance and metabolic homeostasis of cells. NRF2 can activate the expression of a variety of antioxidant enzymes and related genes, such as glutathione S-transferase (GSTs), superoxide dismutase (SODs), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and help cells resist oxidative stress. What is more, KGN can downregulate the expression of miR-146a, which is a microRNA that inhibits the expression of NRF2 by targeting the 3' non-translated region of the NRF2 mRNA. KGN indirectly increases the level of NRF2 protein by inhibiting miR-146a, thereby activating the antioxidant pathway and protecting chondrocytes [13].

4.2. Preparation of KGN

Since KGN is a small molecule compound, it can be synthesized through specific chemical reaction. For example, KGN can be synthesized by a chemical reaction between 4-aminobenzene and phthalic anhydride. However, because of the low solubility, KGN cannot be used as drug directly [14]. To improve the solubility and stability of KGN, it may be packaged by different carriers such as thermogel. Thermogel is a material that can change state when the temperature changes. At low temperature, it is soluble in water, and in body temperature, it will change to gel state. This change is irreversible.

4.3. Preparation of KGN thermogel

KGN was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and then diluted with phosphate-buffered saline PBS (pH 7.4) to form a 5 mM working solution of KGN. KGN working solution was mixed with thermogel solution to prepare KGN gel solution containing 50 µM KGN. The KGN thermogel shows the continuously release of KGN in three weeks, leading to better proliferation of chondrocytes, which produce higher level of COL-2 and GAG. Also, gives a result of lower level of MMP-13 which is an enzyme that can prevent the growth of cartilage [15].

4.4. Comparison between KGN and other small molecule compounds

4.4.1. Advantage

KGN has been found to have a strong ability to promote chondrocytes differentiation. It can effectively promote the mesenchymal stem cells to differentiate to chondrocytes.

Compared to other molecule compounds, KGN could inhibit the reduction of extracellular matrix caused by interleukin-1β(IL-1β).

4.4.2. Disadvantage

The insolubility of KGN leads to uneven distribution of the medicine in the joins, so it needs new delivery systems’ help to increase the bioavailability.

5. Conclusion

Kartogenin (KGN), a promising agent in orthopedic applications, offers a distinct advantage for athletes requiring swift recovery from cartilage injuries. Its mechanism accelerates the differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells into chondrocytes, thereby potentially reducing the recovery time for cartilage tissue. This attribute makes KGN particularly appealing for competitive sports where rapid return to performance is crucial.

In contrast, hydrogels and tissue-engineered scaffolds, while providing essential support structures for cell growth and tissue repair, may not offer the same expedited healing benefits as KGN. Hydrogels, known for their high water content and biocompatibility, serve as a nurturing environment for cell regeneration. Scaffolds, mimicking the extracellular matrix, support cell attachment, proliferation, and differentiation, facilitating the natural healing process.

However, the use of scaffolds, particularly in the form of implants, may present some disadvantages. The physical presence of a scaffold can increase the risk of wound infection, a concern that is less pronounced with KGN, which being a small molecule, does not introduce a foreign body into the system. Additionally, the bulkiness of scaffolds may not be ideal for physically active individuals like athletes, who require minimal interference with their movement.

While hydrogels and scaffolds provide general relief from pain and pressure for a broader population, KGN's targeted approach to enhancing the body's own regenerative capabilities may offer a more tailored solution for those seeking a faster return to their active lifestyles. This underscores the importance of considering the specific needs and circumstances of patients when selecting the most appropriate treatment strategy for cartilage repair.

Acknowledgement

Yiwei Lin, Sipeng Wang and Ziming Lin contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-first authors.

References

[1]. Langer, R., & Vacanti, J. P. (1993). "Tissue Engineering". *Science*, 260(5110), 920-926.

[2]. Atala, A., et al. (2006). "Tissue-engineered autologous bladders for patients needing cystoplasty". *The Lancet*, 367(9518), 1241-1246.

[3]. Hoffman, A. S. (2002). "Hydrogels for biomedical applications". *Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews*, 54(1), 3-12.

[4]. Murdan, S. (2005). "Organogels in drug delivery". *Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery*, 2(3), 489-505.

[5]. Pierre, A. C., & Pajonk, G. M. (2002). "Chemistry of aerogels and their applications". *Chemical Reviews*, 102(11), 4243-4266.

[6]. Joshi, N., Yan, J., Dang, M., Slaughter, K., Wang, Y., Wu, D., Ung, T., Pandya, V., Chen, M. X., Kaur, S., Bhagchandani, S., Alfassam, H. A., Joseph, J., Gao, J., Dewani, M., Yip, R. C., Weldon, E., Shah, P., Shukla, C., Sherman, N. E., Luo, J. N., Conway, T., Eickhoff, J. P., Botelho, L., Alhasan, A. H., Karp, J. M., & Ermann, J. (2024). A Mechanically Resilient Soft Hydrogel Improves Drug Delivery for Treating Post-Traumatic Osteoarthritis in Physically Active Joints. bioRxiv, (), 2024.05.16.594611. Accessed August 11, 20 24.

[7]. Alberts, B., Johnson, A., Lewis, J., Raff, M., Roberts, K., & Walter, P. (2002). Isolating cells and growing them in culture. Molecular Biology of the Cell - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26851/

[8]. Yazdanpanah, Z., Johnston, J. D., Cooper, D. M. L., & Chen, X. (2022). 3D Bioprinted scaffolds for bone tissue Engineering: State-Of-The-Art and Emerging Technologies. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2022.824156

[9]. Flores-Rojas, G. G., Gómez-Lazaro, B., López-Saucedo, F., Vera-Graziano, R., Bucio, E., & Mendizábal, E. (2023). Electrospun Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering: A review. Macromol—A Journal of Macromolecular Research, 3(3), 524–553. https://doi.org/10.3390/macromol3030031

[10]. Tissue Engineering Scaffolds: The Importance of Collagen. (2024, February 19). Intechopen. Retrieved August 5, 2024, from https://www.intechopen.com/online-first/89477

[11]. Santoro, M., Shah, S. R., Walker, J. L., & Mikos, A. G. (2016). Poly (lactic acid) nanofibrous scaffolds for tissue engineering. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 107, 206–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2016.04.019

[12]. Li Y, Cao Z, Tan X, Zhao C, Cao Y, Pan J. Kartogenin potentially protects temporomandibular joints from collagenase-induced osteoarthritis via core binding factor b and runt-related transcription factor 1 binding - A rat model study. Journal of Dental Sciences. 2023;18(4):1553-1560. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2023.03.002

[13]. Hou M, Zhang Y, Zhou X, Liu T, Yang X, Chen X, He F, Zhu X. Kartogenin prevents cartilage degradation and alleviates osteoarthritis progression in mice via the miR-146a/NRF2 axis. Cell Death and Disease. 2021; 12:483.

[14]. Chang H-K, Koh Y-G, Hong H-T, Kang K-T. Preparation of kartogenin-loaded PLGA microspheres and a study of their drug release profiles. Frontiers in Materials. 2024; 11:1364828. doi:10.3389/fmats.2024.1364828

[15]. Wang S-J, Qin J-Z, Zhang T-E, Xia C. Intra-articular Injection of Kartogenin-Incorporated Thermogel Enhancing Osteoarthritis Treatment. Frontiers in Chemistry. 2019; 7:677. doi:10.3389/fchem.2019.00677

Cite this article

Lin,Y.;Wang,S.;Lin,Z. (2025). Hydrogels, Scaffolds, Kartogenin for Regenerative Medicine. Theoretical and Natural Science,72,170-176.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Biological Engineering and Medical Science

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Langer, R., & Vacanti, J. P. (1993). "Tissue Engineering". *Science*, 260(5110), 920-926.

[2]. Atala, A., et al. (2006). "Tissue-engineered autologous bladders for patients needing cystoplasty". *The Lancet*, 367(9518), 1241-1246.

[3]. Hoffman, A. S. (2002). "Hydrogels for biomedical applications". *Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews*, 54(1), 3-12.

[4]. Murdan, S. (2005). "Organogels in drug delivery". *Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery*, 2(3), 489-505.

[5]. Pierre, A. C., & Pajonk, G. M. (2002). "Chemistry of aerogels and their applications". *Chemical Reviews*, 102(11), 4243-4266.

[6]. Joshi, N., Yan, J., Dang, M., Slaughter, K., Wang, Y., Wu, D., Ung, T., Pandya, V., Chen, M. X., Kaur, S., Bhagchandani, S., Alfassam, H. A., Joseph, J., Gao, J., Dewani, M., Yip, R. C., Weldon, E., Shah, P., Shukla, C., Sherman, N. E., Luo, J. N., Conway, T., Eickhoff, J. P., Botelho, L., Alhasan, A. H., Karp, J. M., & Ermann, J. (2024). A Mechanically Resilient Soft Hydrogel Improves Drug Delivery for Treating Post-Traumatic Osteoarthritis in Physically Active Joints. bioRxiv, (), 2024.05.16.594611. Accessed August 11, 20 24.

[7]. Alberts, B., Johnson, A., Lewis, J., Raff, M., Roberts, K., & Walter, P. (2002). Isolating cells and growing them in culture. Molecular Biology of the Cell - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26851/

[8]. Yazdanpanah, Z., Johnston, J. D., Cooper, D. M. L., & Chen, X. (2022). 3D Bioprinted scaffolds for bone tissue Engineering: State-Of-The-Art and Emerging Technologies. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2022.824156

[9]. Flores-Rojas, G. G., Gómez-Lazaro, B., López-Saucedo, F., Vera-Graziano, R., Bucio, E., & Mendizábal, E. (2023). Electrospun Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering: A review. Macromol—A Journal of Macromolecular Research, 3(3), 524–553. https://doi.org/10.3390/macromol3030031

[10]. Tissue Engineering Scaffolds: The Importance of Collagen. (2024, February 19). Intechopen. Retrieved August 5, 2024, from https://www.intechopen.com/online-first/89477

[11]. Santoro, M., Shah, S. R., Walker, J. L., & Mikos, A. G. (2016). Poly (lactic acid) nanofibrous scaffolds for tissue engineering. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 107, 206–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2016.04.019

[12]. Li Y, Cao Z, Tan X, Zhao C, Cao Y, Pan J. Kartogenin potentially protects temporomandibular joints from collagenase-induced osteoarthritis via core binding factor b and runt-related transcription factor 1 binding - A rat model study. Journal of Dental Sciences. 2023;18(4):1553-1560. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2023.03.002

[13]. Hou M, Zhang Y, Zhou X, Liu T, Yang X, Chen X, He F, Zhu X. Kartogenin prevents cartilage degradation and alleviates osteoarthritis progression in mice via the miR-146a/NRF2 axis. Cell Death and Disease. 2021; 12:483.

[14]. Chang H-K, Koh Y-G, Hong H-T, Kang K-T. Preparation of kartogenin-loaded PLGA microspheres and a study of their drug release profiles. Frontiers in Materials. 2024; 11:1364828. doi:10.3389/fmats.2024.1364828

[15]. Wang S-J, Qin J-Z, Zhang T-E, Xia C. Intra-articular Injection of Kartogenin-Incorporated Thermogel Enhancing Osteoarthritis Treatment. Frontiers in Chemistry. 2019; 7:677. doi:10.3389/fchem.2019.00677