1. Introduction

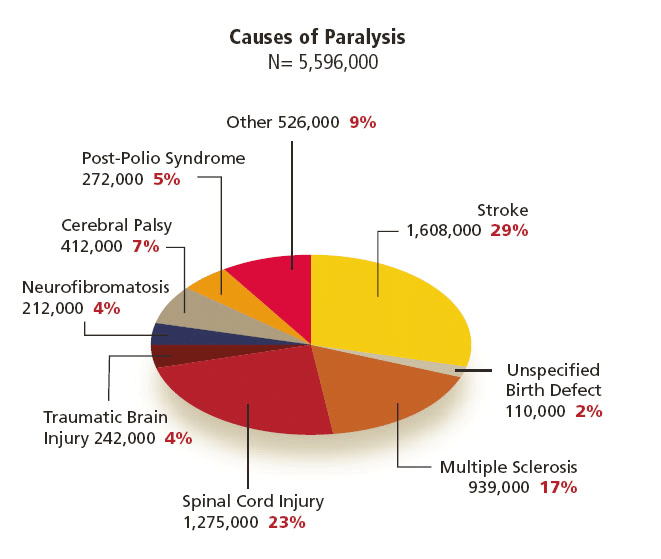

Upper-limb motor impairment, mainly from stroke, traumatic injury, or progressive neurological disease, leads to loss of voluntary motor control for millions and is an increasing global burden. Every year, stroke alone costs more than 890 billion USD [3]. About 5.4 million Americans and over 100 million people worldwide live with paresis or paralysis, and 55–75% of stroke survivors have motor dysfunction, roughly 85% of which affect the upper limb [4-6]. Standard rehabilitation, including physical and occupational therapy, medications, and surgery, often yields only partial recovery in chronic or severe cases, and about 22% of patients develop post-injury depression, which worsens unemployment and social isolation [7].

|

Severity of Injury |

First Year |

Each Subsequent year |

|

High Tetraplegia (C1-C4) ASIS ABC |

$10,064,716 |

$184,891 |

|

Low Tetraplegia (C5-C8) |

$769,351 |

$113,423 |

|

Paraplegia |

$518,904 |

$68,739 |

|

Incomplete motor function (any level) |

$347,484 |

$42,206 |

In response, robotic exoskeletons driven by EEG signals have emerged as technologies capable of amplifying residual neural commands to restore motor function. A 2024 randomized controlled trial in Neurological Research reported that exoskeleton-assisted arm and hand training significantly outperformed the traditional Bobath method in motor recovery, movement quality, and daily functioning among chronic stroke patients. The authors concluded that “high-intensity repetitive arm and hand exercises with an exoskeleton device was safe and feasible,” [9] underscoring the potential of robotic rehabilitation to improve outcomes and reduce the wider economic and social impact of upper-limb paralysis.

2. Design device

2.1. Upper limb exoskeleton design and optimization

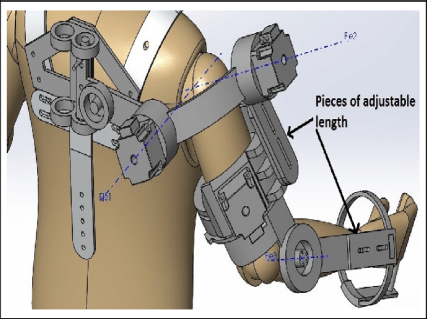

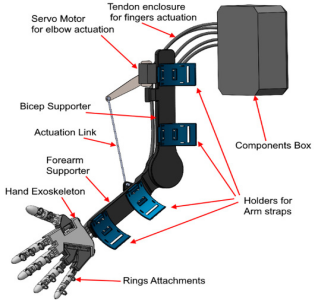

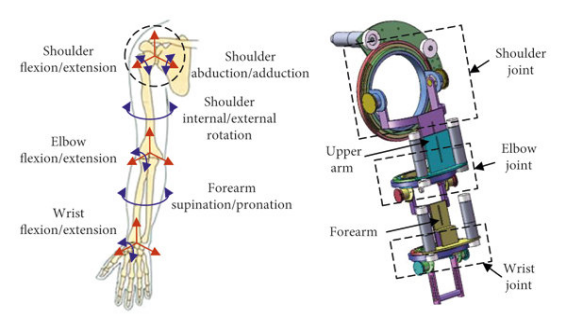

Figure 3. (a) Design of 5-degree-of-freedom upper limb exoskeleton [10], (b) exoskeleton structure design [11], (c) model of the upper limb exoskeleton [12]

Upper-limb exoskeletons are lightweight wearable robots driven by electric motors and cable transmissions. They deliver thousands of precise and repeatable movement repetitions per session. A study found that robotic rehabilitation saved an average of 2352 USD per stroke survivor compared to traditional clinic-based ones, enabling intensive rehabilitation for stroke, spinal cord injury, and neurodegenerative disease without continuous therapist supervision [13].

The exoskeleton spine comprises four vertically stacked motor-drums, each rigidly fixed within 3-D-printed brackets bonded to dorsal armour plates; interposed compliant mesh and segmented inserts let the column track spinal curvature without constraining the wearer. From every drum a high-strength cable is guided over the shoulder, laid along the upper-arm surface, routed through an elbow-mounted pulley, and terminated on the forearm. When the elbow is extended the cable remains slack, preserving free motion; upon flexion the drum retracts the cable, providing graded lifting torque while low-profile guides maintain a snag-free, anatomically congruent line-of-action and evenly distributed mass.

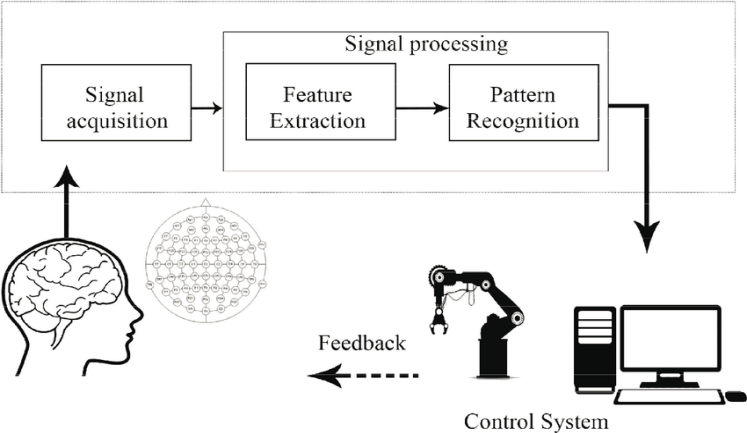

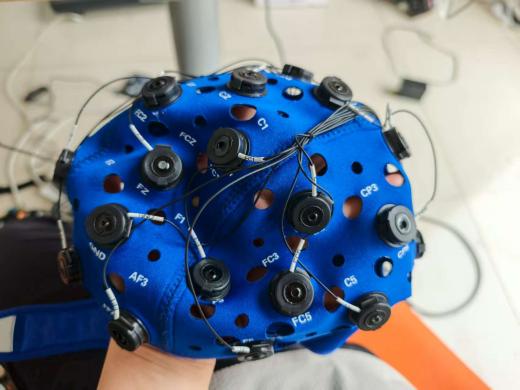

2.2. Non-invasive brain-computer interfaces

A brain-computer interface (BCI) translates neural activity into device commands via signal acquisition, feature extraction, pattern recognition, and output and feedback, enabling individuals with motor impairment to control hardware without muscular effort. Non-invasive BCIs use EEG captured by flexible caps (fabric, elastomer, silicone) with fixed positions and conductive gel or saline to maintain low-impedance, safe, painless contact. EEG arises from synchronized firing of millions of neurons, whose extracellular currents the electrodes pick up and BCIs decode in real time.

|

Electrode |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

|

Name |

Cz |

Fz |

CP5 |

CP6 |

F3 |

F4 |

FC1 |

FC2 |

FC5 |

FC6 |

C3 |

C4 |

GND |

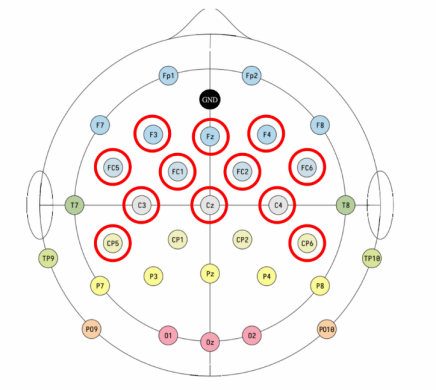

EEG data acquisition and experiment control were implemented using the OpenBCI GUI v6.0.0‑beta.1. A Bluetooth USB dongle linked the Cyton amplifier wirelessly to the host computer, minimizing cable drag. EEG signals were recorded using a 32-channel EEG cap; however, only 12 electrodes were selected for this experiment: Cz, Fz, CP5, CP6, F3, F4, FC1, FC2, FC5, FC6, C3, and C4. These channels were chosen for their relevance to motor and frontal cortical activity. Data were sampled at a rate of 50 Hz to capture sufficient temporal resolution for detecting motor-related EEG features while minimizing data volume and processing load.

3. EEG data processing

3.1. EEG data collection

During EEG data collection, participants listened to a series of audio cues, each indicating a specific task or state to perform. The session started with three minutes of sitting quietly to establish a resting baseline. Next, participants were guided through different forearm movements in three conditions: first in a relaxed state, then in a muscle contraction state (by holding an object), and finally imagining the movement without physical action (motor imagery). The three types of movements included pronation (rotating the forearm inward), flexion-extension (bending and straightening the wrist), and an arm pull (extending the arm then bending it toward the chest). Each movement was performed under the three conditions to capture distinct brain activity patterns related to both physical and imagined actions.

3.2. MATLAB EEG analysis

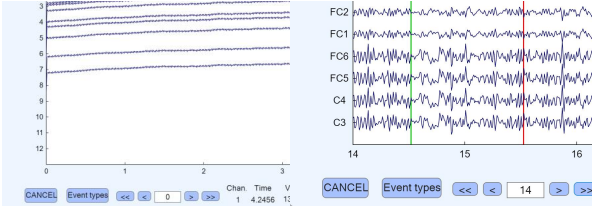

This section describes how the EEG data were processed for analysis. From each OpenBCI recording the twelve EEG channels and a single marker channel were extracted and saved as a 13-channel text file. Each file was imported into EEGLAB and events were read from the marker channel so that marker timing was encoded in the dataset. Standard channel location information was assigned to ensure accurate scalp locations, and the recordings were re-referenced using a common reference to reduce reference-related bias across channels.

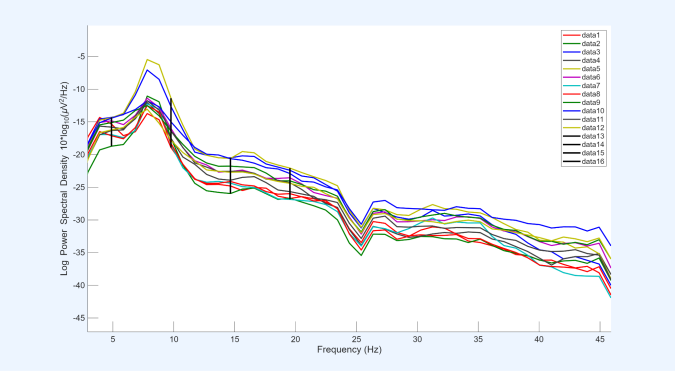

A basic finite-impulse-response (FIR) filtering procedure was applied to prepare the signals for analysis. First, a 4–45 Hz band-pass filter was used to retain neural activity in that range while attenuating slow drifts below 4 Hz and high-frequency noise above 45 Hz. Second, a narrow 24–26 Hz notch filter was applied to suppress a persistent narrowband interference attributed to power-frequency (mains) electrical noise.

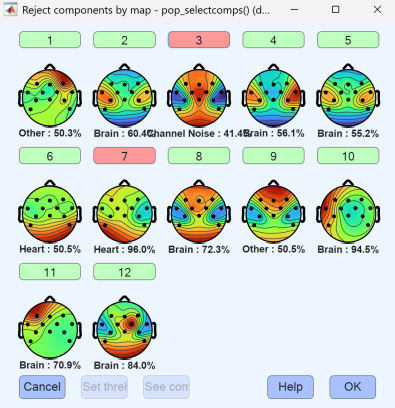

Independent component analysis (ICA) was then performed to separate the data into independent components, and components identified as artifactual or otherwise unwanted were removed. After cleaning, epochs for marker 1 (flexion) and marker 2 (extension) were extracted and used to generate figures and summary metrics, either as a full dataset or by condition.

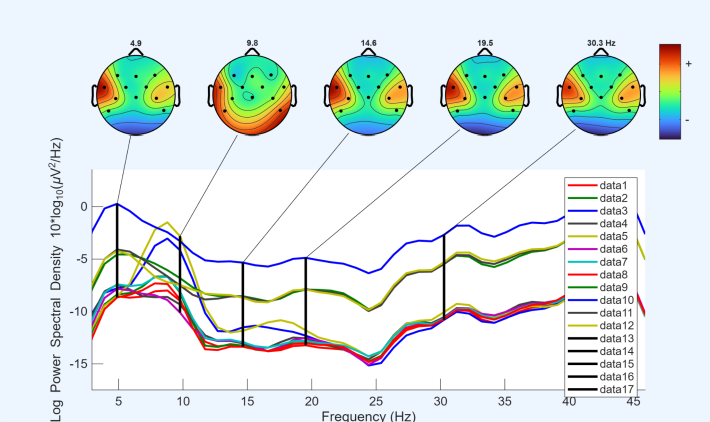

After extracting the epochs, channel spectra and maps were plotted for all 12 EEG channels, with the x-axis representing frequency (Hz) and the y-axis representing log power spectral density. In all datasets, it was observed that channel 3, corresponding to CP5, exhibited relatively higher power across all frequencies compared with the other channels. Based on this observation, CP5 was selected for more detailed analysis in subsequent steps.

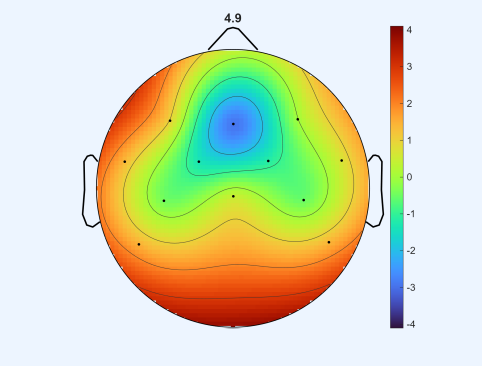

Before performing the three movements, a resting-state condition was recorded, during which participants remained seated quietly without performing any task. This baseline condition, referred to as quiet sitting, provided a reference for comparing neural activity during the subsequent movement tasks.

This map displays how spectral power at 4.9 Hz is distributed across the scalp in the resting state: channel-wise power spectral densities were converted to log power and interpolated to produce the image, with warm colors indicating relatively higher power.

|

T |

A |

LB |

HB |

G |

||

|

1 |

Extension |

-7.083067648 |

-7.596776039 |

-10.98070537 |

-8.534596657 |

-4.801061816 |

|

Flexion |

-5.667733 |

-9.123552571 |

-11.56522126 |

-11.02297016 |

-9.377878362 |

|

|

2 |

Extension |

-9.143906314 |

-9.666302322 |

-16.1834049 |

-17.27517287 |

-16.93147184 |

|

Flexion |

-8.762455723 |

-10.23756847 |

-15.26064384 |

-17.6272132 |

-17.63791124 |

|

|

3 |

Extension |

-8.045027083 |

-10.17172708 |

-17.90189583 |

-21.39124861 |

-21.80061 |

|

Flexion |

-9.334391667 |

-10.83534167 |

-17.71558403 |

-20.84403056 |

-21.50994 |

The table for flexion-extension summarizes the averaged spectral power of five EEG frequency bands—Theta (T), Alpha (A), Low Beta (LB), High Beta (HB), and Gamma (G)—across different task states. Rows 1, 2, and 3 correspond to the three states (relaxed, muscle contraction, imaginative, respectively), each further split into extension and flexion conditions. Data was extracted from EEGLAB channel properties by analyzing each channel over the 3–46 Hz range, calculating the average value for each frequency band per channel. These channel-wise averages were then averaged across all channels to obtain the values presented in the table. This approach allows a concise comparison of how different frequency bands respond across states and movements, providing insight into the temporal and spectral dynamics of brain activity associated with the task.

|

T |

A |

LB |

HB |

G |

||

|

1 |

Inward |

-12.386925 |

-13.64056458 |

-13.04605486 |

-11.46923681 |

-10.91402 |

|

Outward |

-12.20836042 |

-12.76017292 |

-12.24534792 |

-10.82412847 |

-10.005315 |

|

|

2 |

Inward |

-8.228495833 |

-9.2512625 |

-13.04572917 |

-12.09505694 |

-10.949915 |

|

Outward |

-7.7742625 |

-9.472627083 |

-12.90903542 |

-11.54232917 |

-10.30469583 |

|

|

3 |

Inward |

-10.33963542 |

-9.18105625 |

-12.36725069 |

-10.78035069 |

-9.657175 |

|

Outward |

-8.93544375 |

-8.080208333 |

-10.92675903 |

-10.01961597 |

-8.119499167 |

The table for arm pronation presents the averaged spectral power of the five frequency bands across the three states (extension and flexion). Values were calculated using the same channel-wise averaging procedure as for Movement 1, providing a consistent overview of frequency-specific brain activity for this movement.

|

T |

A |

LB |

HB |

G |

||

|

1 |

Extension |

-10.8505 |

-10.3835375 |

-18.42347778 |

-22.44958819 |

-23.51547917 |

|

Flexion |

-11.13955833 |

-10.0888625 |

-18.32694375 |

-22.57051667 |

-23.91181083 |

|

|

2 |

Extension |

-8.44413125 |

-9.18370625 |

-14.18333542 |

-14.77212222 |

-13.40535917 |

|

Flexion |

-6.738960417 |

-8.580566667 |

-13.98199583 |

-14.51395139 |

-13.82022167 |

|

|

3 |

Extension |

-10.0574375 |

-11.0738 |

-13.61762222 |

-12.82398194 |

-11.765395 |

|

Flexion |

-9.596745833 |

-10.52398542 |

-13.73258611 |

-12.65787847 |

-12.5586 |

For arm pull, the table similarly summarizes the average spectral power of Theta, Alpha, Low Beta, High Beta, and Gamma bands across extension and flexion states. The same calculation procedure was applied, allowing comparison across movements and conditions.

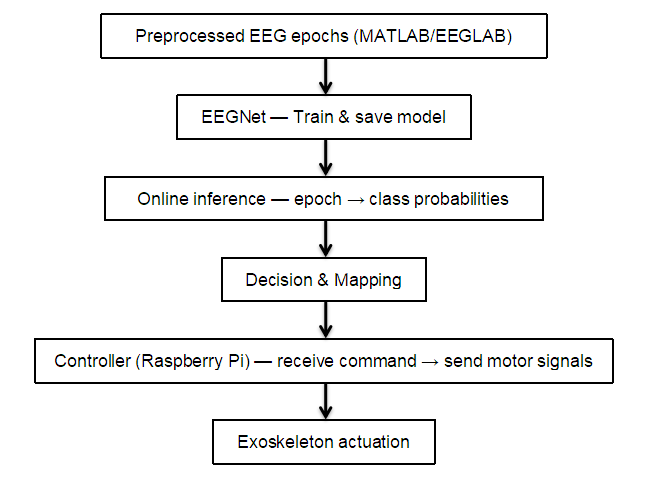

3.3. EEG-Net pytorch

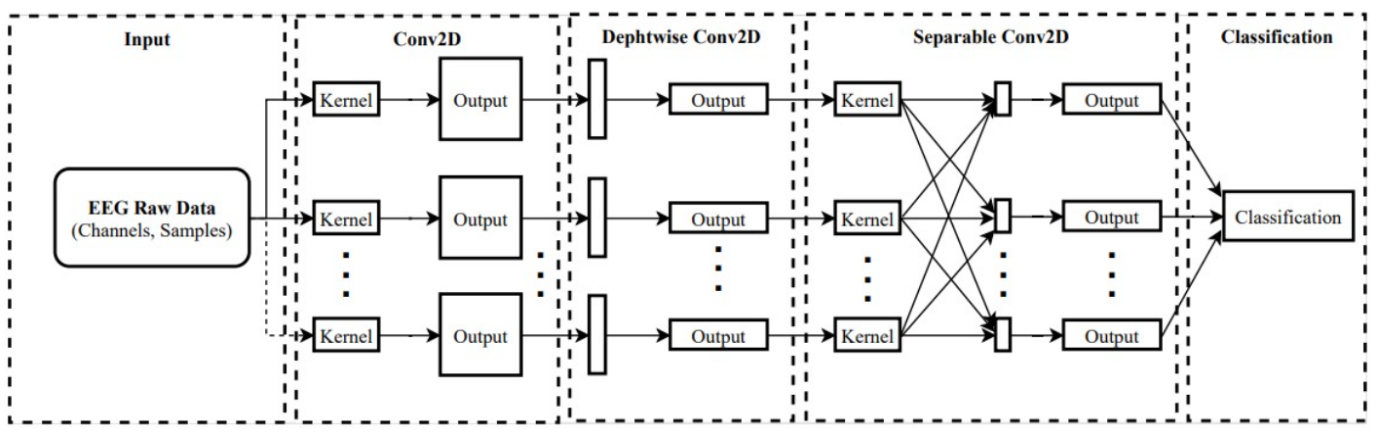

EEGNet is a deep learning model specifically designed for electroencephalogram (EEG) signal processing. It is known for its compactness, strong feature-extraction capability, good generalization performance, and interpretability. By using depthwise separable convolutions, EEGNet reduces model parameters and improves training and inference efficiency while extracting spatiotemporal features from EEG signals. EEGNet performs well across multiple BCI paradigms and maintains high classification accuracy even when training data are limited. It also provides several ways to visualize and interpret learned features consistent with neurophysiological phenomena, helping researchers better understand how EEG relates to brain activity. EEGNet’s flexibility lets it adapt to EEG datasets of different sizes and types and be extended for specific BCI tasks [16].

Figure 16 shows the EEGNet model architecture and highlights its key components and design principles. The diagram visually demonstrates how EEGNet processes EEG signals through a sequence of convolutional and pooling layers to finally perform classification. The architecture efficiently extracts temporal and spatial features from EEG data by using depthwise separable convolutions, significantly reducing the number of parameters while maintaining high performance. Figure 16 also emphasizes the model’s ability to produce interpretable features, which can be visualized through hidden unit activations and convolutional kernel weights. This architecture not only enables EEGNet to generalize across different BCI paradigms, but also ensures the learned features align with known neurophysiological phenomena, validating the model’s robustness and effectiveness in EEG-based BCI applications.

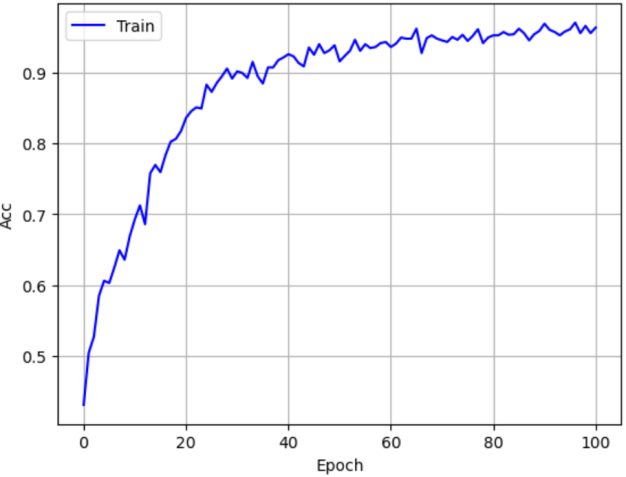

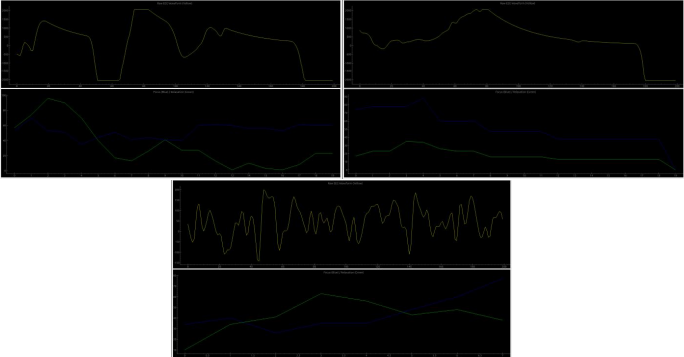

As shown in Figure 17, the learning curve displays the model’s accuracy during training across epochs. The horizontal axis is the number of training epochs, and the vertical axis is model accuracy. The plot shows that EEGNet’s accuracy increases with epochs, indicating continuous learning and optimization. In early training the accuracy rises quickly, then gradually levels off and finally stabilizes at a high value. This indicates the model converges during training and has good learning performance. The model achieves high accuracy on the training set and reaches a stable state, showing that EEGNet can effectively extract features from EEG data and perform classification.

3.4. Experiment design

Before the experiment, EEG data were collected for four states: sitting, flexion/extension, forearm rotation, and retract/extend. For each state, data were recorded under three conditions: relaxed, actual muscle contraction, and motor imagery. A 32-channel cap sampled at 50 Hz to capture detailed EEG signals. Recorded EEG underwent preprocessing: filtering to remove irrelevant frequency components and denoising to reduce environmental interference.

The preprocessed data were input into the EEGNet model for feature extraction and classification. Through model training, we identified EEG feature patterns corresponding to different motion states. During training, model parameters were continuously adjusted to optimize classification performance and ensure accurate recognition of the four states: sitting, flexion/extension, forearm rotation, and retract/extend.

The trained EEGNet model was applied to an exoskeleton control system. The model’s outputs were converted to control signals for the exoskeleton motors, enabling real-time control of the exoskeleton. The exoskeleton responds according to the recognized motion state to assist in completing movements such as flexion/extension.

Figure 19 presents raw EEG (yellow) alongside Focus and Relaxation scores (blue/green) for a cognitive task, an arm extension, and an arm flexion. Transient high-amplitude deflections are identified after a short smoothing step to reduce noise, and the system classifies events by their temporal patterning into motor-related labels (Extend, Bend). The interface displays the running event count and highlights detected motor patterns in real time.

Experimental results show that the EEGNet model can effectively extract features from EEG data and perform classification, thereby enabling control of the exoskeleton.

4. Conclusions and future prospects

We present a low-cost, end-to-end pipeline that converts 32-channel EEG (12 motor/frontal electrodes, 50 Hz, OpenBCI Cyton) into real-time elbow assistance: 4–45 Hz bandpass and 24–26 Hz notch filtering, ICA artifact removal, EEGNet classification on Raspberry Pi, and threshold-triggered commands to MG6012E servomotors driving a cable-driven exoskeleton. Discrete flexion, extension, and rest motions were reproducibly elicited under controlled conditions, validating a lightweight decoding chain that runs on commodity hardware and a garment-integrated, backpack-mounted, soft-segmented frame that delivers anatomically congruent assistance with minimal limb-borne mass and perceived encumbrance.

Limitations include single-site, single-participant prototyping with a sparse 12-electrode/50-Hz montage that sacrifices spatiotemporal resolution, fixed-threshold detection vulnerable to EEG drift and artifact, and only one experimental run with triplicates, yielding insufficient statistical power and uncertain cross-user generalizability. Future work will enroll a larger end-user cohort, adopt adaptive or hybrid classifiers, incorporate haptic/auditory feedback, and transition to wireless, AI-calibrated hardware to advance this low-complexity EEG-to-exoskeleton pipeline toward robust clinical assistive use.

References

[1]. Rouse, Adam. (2012). Neural Adaptation and the Effect of Interelectrode Spacing on Epidural Electrocorticography for Brain-Computer Interfaces.

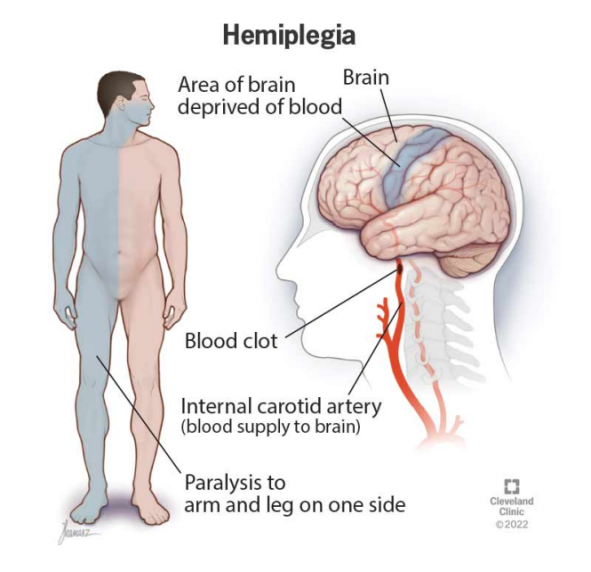

[2]. Cleveland Clinic. “Hemiplegia: Definition, Causes, Symptoms & Treatment.” Cleveland Clinic, 23 July 2022, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/symptoms/23542-hemiplegia.

[3]. Feigin, Valery L et al. “World Stroke Organization: Global Stroke Fact Sheet 2025.” International journal of stroke : official journal of the International Stroke Society vol. 20, 2 (2025): 132-144. doi: 10.1177/17474930241308142

[4]. Armour, Brian S et al. “Prevalence and Causes of Paralysis-United States, 2013.” American journal of public health vol. 106, 10 (2016): 1855-7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303270

[5]. GBD 2019 Stroke Collaborators. “Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.” The Lancet. Neurology vol. 20, 10 (2021): 795-820. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00252-0

[6]. Tang, Qingqing et al. “Research trends and hotspots of post-stroke upper limb dysfunction: a bibliometric and visualization analysis.” Frontiers in neurology vol. 15 1449729. 2 Oct. 2024, doi: 10.3389/fneur.2024.1449729

[7]. Williams, Ryan, and Adrian Murray. “Prevalence of depression after spinal cord injury: a meta-analysis.” Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation vol. 96, 1 (2015): 133-40. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.08.016

[8]. “Costs of Living with a Spinal Cord Injury | Reeve Foundation.” Christopher & Dana Reeve Foundation, www.christopherreeve.org/todays-care/living-with-paralysis/costs-and-insurance/costs-of-living-with-spinal-cord-injury/.

[9]. Akgün, İrem et al. “Exoskeleton-assisted upper limb rehabilitation after stroke: a randomized controlled trial.” Neurological research vol. 46, 11 (2024): 1074-1082. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2024.2381385

[10]. Luengas, Yukio & López, Ricardo & Salazar, Sergio & Lozano, R.. (2018). Robust controls for upper limb exoskeleton, real-time results. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part I: Journal of Systems and Control Engineering. 232. 095965181875886. 10.1177/0959651818758866.

[11]. Imtiaz, M. S. b., Babar Ali, C., Kausar, Z., Shah, S. Y., Shah, S. A., Ahmad, J., Imran, M. A., & Abbasi, Q. H. (2021). Design of Portable Exoskeleton Forearm for Rehabilitation of Monoparesis Patients Using Tendon Flexion Sensing Mechanism for Health Care Applications. Electronics, 10(11), 1279. https: //doi.org/10.3390/electronics10111279

[12]. Fang, Qianqian & Li, Ge & Xu, Tian & Zhao, Jie & Cai, Hegao & Zhu, Yanhe. (2019). A Simplified Inverse Dynamics Modelling Method for a Novel Rehabilitation Exoskeleton with Parallel Joints and Its Application to Trajectory Tracking. Mathematical Problems in Engineering. 2019. 1-10. 10.1155/2019/4602035.

[13]. Cano-de-la-Cuerda, Roberto, et al. “Economic Cost of Rehabilitation with Robotic and Virtual Reality Systems in People with Neurological Disorders: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Clinical Medicine, vol. 13, no. 6, 2024, p. 1531. https: //doi.org/10.3390/jcm13061531.

[14]. Ajali-Hernández, Nabil & Travieso, Carlos. (2022). Analysis of Brain Computer Interface Using Deep and Machine Learning. 10.5772/intechopen.106964.

[15]. “High Density EEG Caps for Researchers.” BESDATA, besdatatech.com/high-density-eeg-caps-for-researchers/.

[16]. Lawhern, Vernon & Solon, Amelia & Waytowich, Nicholas & Gordon, Stephen & Hung, Chou & Lance, Brent. (2018). EEGNet: a compact convolutional neural network for EEG-based brain–computer interfaces. Journal of Neural Engineering. 15. 10.1088/1741-2552/aace8c.

Cite this article

Sun,D. (2025). Development and Experimental Validation of a Non-Invasive Brain–Computer Interface for Upper-Limb Exoskeleton Control. Theoretical and Natural Science,152,153-165.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICMMGH 2026 Symposium: Biomedical Imaging and AI Applications in Neurorehabilitation

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Rouse, Adam. (2012). Neural Adaptation and the Effect of Interelectrode Spacing on Epidural Electrocorticography for Brain-Computer Interfaces.

[2]. Cleveland Clinic. “Hemiplegia: Definition, Causes, Symptoms & Treatment.” Cleveland Clinic, 23 July 2022, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/symptoms/23542-hemiplegia.

[3]. Feigin, Valery L et al. “World Stroke Organization: Global Stroke Fact Sheet 2025.” International journal of stroke : official journal of the International Stroke Society vol. 20, 2 (2025): 132-144. doi: 10.1177/17474930241308142

[4]. Armour, Brian S et al. “Prevalence and Causes of Paralysis-United States, 2013.” American journal of public health vol. 106, 10 (2016): 1855-7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303270

[5]. GBD 2019 Stroke Collaborators. “Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.” The Lancet. Neurology vol. 20, 10 (2021): 795-820. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00252-0

[6]. Tang, Qingqing et al. “Research trends and hotspots of post-stroke upper limb dysfunction: a bibliometric and visualization analysis.” Frontiers in neurology vol. 15 1449729. 2 Oct. 2024, doi: 10.3389/fneur.2024.1449729

[7]. Williams, Ryan, and Adrian Murray. “Prevalence of depression after spinal cord injury: a meta-analysis.” Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation vol. 96, 1 (2015): 133-40. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.08.016

[8]. “Costs of Living with a Spinal Cord Injury | Reeve Foundation.” Christopher & Dana Reeve Foundation, www.christopherreeve.org/todays-care/living-with-paralysis/costs-and-insurance/costs-of-living-with-spinal-cord-injury/.

[9]. Akgün, İrem et al. “Exoskeleton-assisted upper limb rehabilitation after stroke: a randomized controlled trial.” Neurological research vol. 46, 11 (2024): 1074-1082. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2024.2381385

[10]. Luengas, Yukio & López, Ricardo & Salazar, Sergio & Lozano, R.. (2018). Robust controls for upper limb exoskeleton, real-time results. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part I: Journal of Systems and Control Engineering. 232. 095965181875886. 10.1177/0959651818758866.

[11]. Imtiaz, M. S. b., Babar Ali, C., Kausar, Z., Shah, S. Y., Shah, S. A., Ahmad, J., Imran, M. A., & Abbasi, Q. H. (2021). Design of Portable Exoskeleton Forearm for Rehabilitation of Monoparesis Patients Using Tendon Flexion Sensing Mechanism for Health Care Applications. Electronics, 10(11), 1279. https: //doi.org/10.3390/electronics10111279

[12]. Fang, Qianqian & Li, Ge & Xu, Tian & Zhao, Jie & Cai, Hegao & Zhu, Yanhe. (2019). A Simplified Inverse Dynamics Modelling Method for a Novel Rehabilitation Exoskeleton with Parallel Joints and Its Application to Trajectory Tracking. Mathematical Problems in Engineering. 2019. 1-10. 10.1155/2019/4602035.

[13]. Cano-de-la-Cuerda, Roberto, et al. “Economic Cost of Rehabilitation with Robotic and Virtual Reality Systems in People with Neurological Disorders: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Clinical Medicine, vol. 13, no. 6, 2024, p. 1531. https: //doi.org/10.3390/jcm13061531.

[14]. Ajali-Hernández, Nabil & Travieso, Carlos. (2022). Analysis of Brain Computer Interface Using Deep and Machine Learning. 10.5772/intechopen.106964.

[15]. “High Density EEG Caps for Researchers.” BESDATA, besdatatech.com/high-density-eeg-caps-for-researchers/.

[16]. Lawhern, Vernon & Solon, Amelia & Waytowich, Nicholas & Gordon, Stephen & Hung, Chou & Lance, Brent. (2018). EEGNet: a compact convolutional neural network for EEG-based brain–computer interfaces. Journal of Neural Engineering. 15. 10.1088/1741-2552/aace8c.