1. Introduction

With its 1.4 billion population in China, the healthcare coverage of basic medical insurance has reached 95%, provided by public funding from the government. Basic statutory medical insurance is divided into two categories: Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance (UEBMI) and Urban-Rural Resident Basic Medical Insurance (URRBMI). The UEBMI, which is funded by payroll taxes and offers health insurance with a full benefits package to all urban employees, government agencies, state-owned firms, and private enterprises in a tailored manner, is obligatory for both employers and employees to enroll in. Everyone must contribute a percentage to their medical savings account (MSA), which is primarily used for out-of-pocket payments for outpatient services and drug purchases. Employers contribute a percentage to the MSA, and the remaining payroll taxes on employers are contributed to the Social Pooling Accounts [1]. All other residents are freely eligible to participate in URRBMI, which is primarily funded by central and municipal governments through individual premium subsidies, independent of their age or employment situation. The New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme (NRCMS) and the Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance (URBMI) have been combined to create the URRBMI, which aims to close the gap between urban and rural areas, increase the risk pool, and lower administrative expenses [2]. URRBMI covers primary, specialty, hospital, mental healthcare, prescription drugs, and traditional Chinese medicine with a higher deductible and lower coinsurance rate than UEBMI but with a subsidy from the government for out-of-pocket expenses. Even with the effort of integration to reduce disparities, the urban-rural gap in terms of quality has not significantly reduced.

Access to care is more equivalent between rural and urban areas through integration, but it would still impact the reimbursement rate and out-of-pocket payments depending on where care was received. A study showed that the quality and outcomes of health services are limited, although integration increases healthcare utilization in rural areas, especially for elderly or middle-aged people in rural areas [3]. Long-term care such as cancer screening and treatments is less accessible in rural settings, especially due to unequal development and fewer secondary and tertiary hospitals that can provide more comprehensive services. Primary hospitals present in rural settings are mainly community hospitals and village clinics with minimal health care resources and rehabilitation services and are often unable to perform quality diagnoses. As a result, rural populations frequently have to travel to urban regions for long-term care, catastrophic health problems, and the treatment of chronic diseases. With such conditions, the incidence of catastrophic healthcare expenditures increased 1.5-fold in rural residents with chronic diseases, which induced the individual and their family to become poorer in comparison with the average population [4]. Secondary hospitals that are in mid- to large-size cities are also responsible for medical education, which causes an outflow of rural medical students to urban medical schools and hospitals. In this review, the author examines potential reasons for healthcare disparities between China’s rural and urban areas, contrasts the approaches used in other nations with comparable problems, and offers some suggestions for closing the gaps between urban and rural areas’ access to medical insurance services.

2. Disparity between urban and rural healthcare service

2.1. Rural migration to urban areas with restriction of Hukou

Despite the two statutory schemes with different advantages and disadvantages, the benefits package is primarily determined by the local government and ties strongly with the Hukou System in China as a household registration program, which is an unequal and discriminatory system that limits migrants from rural to urban. The hukou status of individuals depends on the location in which they were born [5]. The Hukou system denies the rights of rural migrants to healthcare services. Most rural migrants may have UEBMI with greater access and better reimbursement, but they still have a rural Hukou, limiting access to certain healthcare services and increasing out-of-pocket payments. Therefore, to receive better healthcare services, many people migrate between the city of employment and the registered location of Hukou, where they can get better reimbursement and gain access to certain services. And since many rural areas do not have adequate equipment of the same quality as urban areas, migrants are unable to receive comprehensive and quality care even when they have access to UEBMI.

2.2. Physician shortages in rural areas

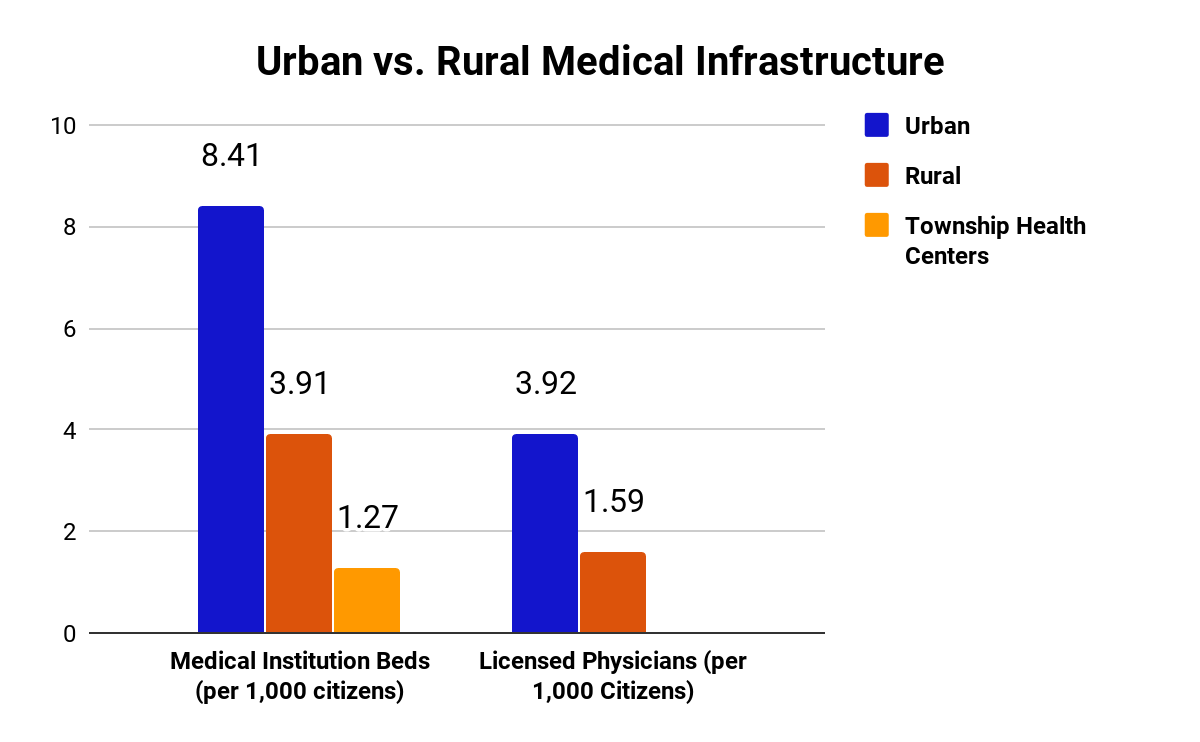

The physician density in China on average was around 2.9 physicians per thousand population in 2020 [6]. Physician density is increasing every year, and the disparities are decreasing between cities and countries, with government emphasis on healthcare human resources. But the substantial urban-rural maldistribution of physicians is still existing, with 3.92% of licensed physicians in urban areas in comparison with only 1.59 licensed physicians in rural areas (figure 1). Village doctors, who are trained only with a technical degree in medical and paramedical treatment, are often the only accessible providers in rural areas, especially in poor areas. Less rural but still considered rural areas would have primary hospitals that are able to perform some elective services. The expansion of village clinics into rural areas is significantly lower than the development of hospitals in urban areas [7]. Although they are only permitted to practice in village clinics with scarce technology and equipment, village doctors resemble “barefoot doctors” and take responsibility for almost all primary and preventative care [1]. They may refer patients to secondary or tertiary hospitals if treatments are beyond their abilities. But the physicians in village clinics are distrusted as understaffed and unequipped, leading patients to go directly to comprehensive hospitals in the city that incur greater health expenditures [4]. The government is increasingly recommending programs for medical graduates to practice in village clinics or even more rural areas for 1-2 years after graduation. The program was initially intended to distribute better physician resources and incentives to medical graduates to work in rural settings. But because of low salaries and rural conditions, these medical graduates usually go back to urban areas and rarely come back to support rural healthcare.

Figure 1. Adapted from national bureau of statistics, healthcare infrastructure differences between urban and rural areas [4].

3. Comparative Countries Policies

3.1. Norway

Norway is a developed high-income nation in Europe, ranking 2nd with a score of 97 in the Healthcare Access and Quality (HAQ) index by the Lancet [8]. Much of its land is rural and thus serves as a good example for comparative rural and urban healthcare. Norway provides universal health care to all citizens through the publicly funded National Insurance Scheme (NIS). NIS is mostly financed by decentralized general taxation at the national, municipal, and county levels. There are small out-of-pocket payments that are capped. Individuals can get private voluntary supplemental health insurance through their employer or purchase it individually. These private insurances are mainly used to avoid the wait times for specialist consultations and elective surgery, as well as for dental and vision care. These services, especially dental and vision, are not included in the benefits package for adult citizens but are included for children [1]. Compared with Norway, the Chinese benefits package isn’t as comprehensive as Norway’s because the services included in the Chinese benefits package are broad but not deep. Some tooth extraction and optometry services are covered, but children are not prioritized.

The Norwegian healthcare system is unified under one single pool with only one national scheme. Compared with China, although large areas in Norway are rural, there are no separate healthcare services between cities and countries. And the practice of rural medicine is quite honored in its healthcare system. Healthcare services in Norway have been geared toward both urbanization and rural poor areas. Specialist care transformed into state enterprises, which increased medical workforce centralization in urban areas [9]. There is no such movement in China because of its large population and large geographical areas, dividing the southeast to be better urbanized compared to the western region of China. If China has adapted to become an urbanized country, it would create a greater medical burden in rural areas.

Norway’s healthcare quality and access are ranked highly, according to the Lancet, but it has no internal quality assessment tool. For instance, for certain elective procedures, the patient may have to drive a long time to get to the clinic because of the maldistribution. Presumably, the HAQ index is ranked highly because of its small population and universal coverage. But Norway’s physician density is also high, with 5 physicians per thousand citizens, almost twice the ratio of China [1]. This ratio is one of the highest among EU nations and in the world. Meanwhile, Norway also has a maldistribution of physician resources between urban (7) and rural (3.8) areas [1]. This ratio is about the same as in China, but with much better physician resources and much more emphasis on physician education. This is undoubtedly the collaborative result of the universities and academies. To minimize the gap between medical practice in rural areas and academic theory, Norway established the National Centre of Rural Medicine (NCRM), which was sponsored by the University of Tromsø, and recruited doctors to enhance the medical knowledge of undergraduates in rural areas. Many other significant universities in Norway have also adopted the program to solve the problem of physician shortages in some areas [9]. NCRM focuses on the development of networking, education, and research in the rural health system, which in turn promotes the recruitment of rural practitioners and contributes to the quality of rural healthcare [10]. This inadvertent way emphasizes the role of rural medicine much differently than in China. Although efforts to promote rural medicine are conducted by higher education institutions, some compulsory aspects of it make the process unfavourable for medical graduates. Also, there was limited opportunity for medical undergraduates to learn about rural medicine because rural medicine is generally underdeveloped and most hands-on experiences are done in secondary or tertiary hospitals.

The Norwegian system emphasizes physician-work-life balance. Physicians have limited hours of work in a day, which may seem to limit access, but Norwegians are still able to get same-day appointments and necessary emergency care. Norway also has much more general practitioners than China. In some views, Norway is falling short of the number of specialists, but the general practitioners can provide comprehensive primary and preventative care for the population [11]. In comparison, most doctors are specialists, and the number of primary care physicians and general practitioners is very low. Typically, people go straight to specialists in public hospitals and rarely use general practitioners. Even if the village clinics resemble a primary care situation, the quality of village clinics and the training for village doctors are insufficient to provide the care Norwegian general practitioners provide.

3.2. Brazil

Brazil, with much of its rural areas, large geography, and large population, also serves as a comparative country for disparities. With the help of Sistema nico de Sade (SUS), Brazil attained universal healthcare in the 1980s and 1990s. SUS auto-enrolls all citizens and visitors to access all its healthcare services. Individuals are allowed to purchase voluntary health insurance or work benefits. The healthcare system is mainly financed by government taxes at the municipal, federal, and state levels. The benefits package for Brazil is much more comprehensive compared to China and even other nations, not only including dental and vision but also some elective surgery such as organ transplants, renal dialysis, and blood therapy. Brazil even offers free HIV/AIDS medication and subsidizes medication for long-term illnesses [12]. From this standpoint, it presents a much more comprehensive and inclusive healthcare system. It has no separate schemes or systems built to differentiate between rural and urban health insurance. But the problems for health disparities lie deeply in discrimination against rural residents, mainly black Brazilians, and homeless people, as well as the LGBTQ group [13].

Brazil’s physician density is 2.18 physicians per thousand residents, which is like but a little lower than that of China. Nevertheless, the percentage of general practitioners (37.5%) is much greater than the 3.5% of general practitioners in China [14]. Like China, the distribution of physician resources is concentrated in big and developed cities, which are the main locations of medical education. The physician density between urban and rural settings is extremely skewed (0.58% vs. 3.44%) [12]. Child health and maternal health in the rural Amazon areas also call for attention [15]. The Brazilian government has initiated efforts such as expanding primary care and ensuring the quality of primary care by introducing pay-for-performance programs, such as the family health teams [16]. The program of family health teams could be extremely useful for improving quality in rural China. The importance of such community/family health workers and health teams would offer greater possibilities in rural China, as the concept of community health workers is not as well implemented as in Brazil. These family health workers also offer home visits, which is hard to implement in China due to the large population but could be implemented for complex and extreme poverty cases. The government has also regulated the location of medical schools by incentivizing the opening of medical schools where health care is most needed, which can also be seen as a lesson for physician training in China. Similar to Canada, Brazil has begun to draw physicians and healthcare workers from other nations to its rural areas to ensure access to such areas. China has not begun these sorts of programs with its strict rules for foreign visitors and scholars. Meanwhile, lots of the younger population are brain-drained to become healthcare workers in other nations, such as the U.S. and Canada, incentivized by high salaries. As for quality control, the Healthy Ministry uses a performance index to track parameters such as effects, access, and equity [12]. Although China also uses similar measures, the corruption within the political system puts the statistics of these measures into doubt. And the ministry of health in China needs to present a clearer calculation index for such quality control that can be presented in each hospital and clinic as the ones in Brazil.

4. Policy Recommendations

Expanding primary care physicians to rural areas would be extremely beneficial to the current healthcare system in China. The expansion of primary care in Brazil and the already comprehensive care provided by general practitioners in Norway serve as examples that led to great improvements in access and quality. Initiatives such as reforms for more opportunities for medical students to pursue general practitioners could be used as a stepping stone to expand primary care [14]. The education of village doctors should also be considered recommended because these village doctors are often seen as the only source of care in poor or rural areas.

Drawing lessons from both Brazil and Norway, China could also implement a better incentive scheme, encourage younger people to become village doctors, and eliminate compulsory programs for rural experiences prior to entering actual hospitals. The intended purpose of such programs shouldn’t be to use these young medical graduates as a healthcare source in rural areas. Instead, these programs should be introduced prior to graduation to inform students of the importance of rural medicine in reaching better health outcomes and reducing disparities in the contemporary system. The government could also use higher salaries to incentivize healthcare workers already in the field to support rural health, such as through a better pay-for-performance system in rural conditions to ensure quality. With no such lucrative incentivization, there would hardly be any physicians returning to rural settings. A similar strategy could also be implemented for foreign physicians to practice in China. If China can lower the restrictions or waive restrictions for such physicians to come and practice in the country, it may lead to better health outcomes in both urban and rural settings. Attracting physicians from foreign nations could also drive some native physicians to rural areas, depending on the use of such policies.

The importance of community healthcare workers should also be more prominent in rural areas. These community healthcare workers could resemble the family health team in Brazil, but with fewer resources (as a start) and fewer restrictions on physician licensing. As many researchers from Norway and Brazil suggest, telehealth or e-health should also be considered as a strategy for improving rural health [17]. Thus, the need for better technology and a stable connection for telehealth lies in the foundational work for ensuring access to care in most rural settings.

5. Summary

The Chinese government has worked tirelessly in recent years to improve healthcare services, particularly through the establishment of national medical insurance programs. However, disparities between rural and urban areas in China still exist, and it will be necessary to take measures to eliminate regional differences in the future, including regulation of medical resource allocation, development of country doctor education, and reconstruction of medical networks. Some of the policies taken in Norway and Brazil are worthy of learning and imitation in China. It’s important to provide a better incentive scheme for medical graduates working in the country to expand primary care physicians in undeveloped locations. Another benefit policy should be considered to attract physicians and students from other nations as community health workers in rural areas.

References

[1]. Emanuel E J 2020 Norway, China. Which country has the world’s Best Health Care? Essay. BBS. Public Affairs.

[2]. Tikkanen Roosa Tikkanen R, Osborn R, Mossialos E, Djordjevic A, and Wharton G A 2020 China. The Commonwealth Fund.

[3]. Zhao M, Liu B, Shan L, Li C, Wu Q, Hao Y, Chen Z, Lan L, Kang Z, Liang L, Ning N, and Jiao M 2019 Can integration reduce inequity in healthcare utilization? Evidence and hurdles in China. BMC. Health. Serv. Res. 19(1):654.

[4]. Lee C, Tong A, and Wang M 2018 Chinese healthcare: The rural reality - collective responsibility. Collective Responsibility.

[5]. Luo D, Deng J, and Becker ER 2021 Urban-rural differences in healthcare utilization among beneficiaries in China’s new cooperative medical scheme. BMC. Public. Health. 21(1):1519.

[6]. Zhang, W 2022 China: Physicians density. Statista.

[7]. Ying M, Wang S, Bai C, and Li Y 2020 Rural-urban differences in health outcomes, healthcare use, and expenditures among older adults under universal health insurance in China. PLoS. One. 15(10):e0240194.

[8]. GBD 2016 Healthcare Access and Quality Collaborators 2018 Measuring performance on the Healthcare Access and Quality Index for 195 countries and territories and selected subnational locations: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 391(10136):2236-2271.

[9]. Aaraas IJ, Swensen E 2008 National Centre of Rural Medicine in Norway: a bridge from rural practice to the academy. Rural. Remote. Health. 8(2):948.

[10]. Fosse A, Abelsen B, Gaski M, and Grimstad H 2023 Educational interventions to ensure provision of doctors in rural areas - a systematic review. Rural. Remote. Health. 23(1):8125.

[11]. Tikkanen Roosa Tikkanen R, Robin R, Mossialos E, Djordjevic A, and Wharton GA 2020 Norway. The Commonwealth Fund.

[12]. Tikkanen R, Osborn R, Mossialos E, Djordjevic A, and Wharton G A 2020 Brazil. The Commonwealth Fund.

[13]. Coimbra CEA Jr 2018 Rural Health in Brazil: a still relevant old subject. Rev. Saude. Publica. 52(Suppl 1):2s.

[14]. Wang S, Fu X, Liu Z, Wang B, Tang Y, Feng H, and Wang J 2017 General practitioner education reform in China: Most undergraduate medical students do not choose general practitioner as a career under the 5+3 model. Health. Professions. Education. 4(2):127-132.

[15]. Garnelo L, Parente RCP, Puchiarelli MLR, Correia PC, Torres MV, and Herkrath FJ 2020 Barriers to access and organization of primary health care services for rural riverside populations in the Amazon. Int. J. Equity. Health. 19(1):54.

[16]. Prudence MN 2016 An Assessment of Equity in the Brazilian Healthcare System: Redistribution of Healthcare Professionals to Address Inequities in Remote and Rural Healthcare. Clinical. Social. Work. and Health. Intervention. 7(4):25–32.

[17]. Myrvang R, and Rosenlund T 2007 How can eHealth benefit rural areas - a literature overview from Norway. Norwegian Centre for E-health Research.

Cite this article

Wang,T. (2023). Access and quality of healthcare in China: Rural and urban disparities. Theoretical and Natural Science,17,209-214.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Modern Medicine and Global Health

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Emanuel E J 2020 Norway, China. Which country has the world’s Best Health Care? Essay. BBS. Public Affairs.

[2]. Tikkanen Roosa Tikkanen R, Osborn R, Mossialos E, Djordjevic A, and Wharton G A 2020 China. The Commonwealth Fund.

[3]. Zhao M, Liu B, Shan L, Li C, Wu Q, Hao Y, Chen Z, Lan L, Kang Z, Liang L, Ning N, and Jiao M 2019 Can integration reduce inequity in healthcare utilization? Evidence and hurdles in China. BMC. Health. Serv. Res. 19(1):654.

[4]. Lee C, Tong A, and Wang M 2018 Chinese healthcare: The rural reality - collective responsibility. Collective Responsibility.

[5]. Luo D, Deng J, and Becker ER 2021 Urban-rural differences in healthcare utilization among beneficiaries in China’s new cooperative medical scheme. BMC. Public. Health. 21(1):1519.

[6]. Zhang, W 2022 China: Physicians density. Statista.

[7]. Ying M, Wang S, Bai C, and Li Y 2020 Rural-urban differences in health outcomes, healthcare use, and expenditures among older adults under universal health insurance in China. PLoS. One. 15(10):e0240194.

[8]. GBD 2016 Healthcare Access and Quality Collaborators 2018 Measuring performance on the Healthcare Access and Quality Index for 195 countries and territories and selected subnational locations: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 391(10136):2236-2271.

[9]. Aaraas IJ, Swensen E 2008 National Centre of Rural Medicine in Norway: a bridge from rural practice to the academy. Rural. Remote. Health. 8(2):948.

[10]. Fosse A, Abelsen B, Gaski M, and Grimstad H 2023 Educational interventions to ensure provision of doctors in rural areas - a systematic review. Rural. Remote. Health. 23(1):8125.

[11]. Tikkanen Roosa Tikkanen R, Robin R, Mossialos E, Djordjevic A, and Wharton GA 2020 Norway. The Commonwealth Fund.

[12]. Tikkanen R, Osborn R, Mossialos E, Djordjevic A, and Wharton G A 2020 Brazil. The Commonwealth Fund.

[13]. Coimbra CEA Jr 2018 Rural Health in Brazil: a still relevant old subject. Rev. Saude. Publica. 52(Suppl 1):2s.

[14]. Wang S, Fu X, Liu Z, Wang B, Tang Y, Feng H, and Wang J 2017 General practitioner education reform in China: Most undergraduate medical students do not choose general practitioner as a career under the 5+3 model. Health. Professions. Education. 4(2):127-132.

[15]. Garnelo L, Parente RCP, Puchiarelli MLR, Correia PC, Torres MV, and Herkrath FJ 2020 Barriers to access and organization of primary health care services for rural riverside populations in the Amazon. Int. J. Equity. Health. 19(1):54.

[16]. Prudence MN 2016 An Assessment of Equity in the Brazilian Healthcare System: Redistribution of Healthcare Professionals to Address Inequities in Remote and Rural Healthcare. Clinical. Social. Work. and Health. Intervention. 7(4):25–32.

[17]. Myrvang R, and Rosenlund T 2007 How can eHealth benefit rural areas - a literature overview from Norway. Norwegian Centre for E-health Research.